Abstract

Background and Objective

The pathology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a neurodegenerative disorder affecting motor neurons, comprises aberrant accumulations of neurofilaments; mutations in the peripherin subunit of neurofilaments have been identified in some forms of ALS. Recently, the Amyloid-β Precursor Protein (APP), a key element for the pathology of Alzheimer's disease (AD), was linked to ALS. Here, we provide evidence that the generation of the N-terminal fragment of APP, sAPP, relies on peripherin neurofilaments. This finding could relate to a novel molecular mechanism dysregulated in ALS and/or AD.

Methods and Results

The production and the fate of sAPP were studied with the brainstem-derived, neuronal cell line, CAD, which expresses endogenous peripherin. We show that sAPP and C-terminal fragments (CTF) are generated to a large extent in the neuronal soma. We find that sAPP, but not CTF, associates with filamentous structures that delineate the nuclear lamina, extend to the cell periphery, and immunostain for peripherin. The depletion of peripherin with siRNA eliminates the filamentous immunostaining of sAPP.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that a fraction of APP is cleaved by β-secretase in the soma, and that the generated sAPP becomes associated with perinuclear peripherin neurofilaments. These findings link the metabolism of APP – which is dysregulated in AD - to the organization of neurofilaments – which is abnormal in ALS - and suggest a possible crosstalk/overlap between the molecular mechanisms of these diseases.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Amyloid-β Precursor Protein, Intraneuronal amyloid-β peptide, Neurofilaments, Peripherin, Mechanism of neurodegenerative diseases, Motor neurons, Disease cross-talk

Background and Objective

Most neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), have currently no cure. This situation is largely explained by our lack of sufficient knowledge about the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of these diseases. Neuronal degeneration and death, possibly linked to altered trafficking and metabolism of Amyloid-β Precursor Protein (APP) leading to the generation of potentially toxic APP fragments, is considered a probable cause of the profound memory deficits characteristic to AD [1, 2]. In ALS, upper and lower motor neurons are progressively lost by poorly understood mechanisms that, among others, lead to the disruption of the neurofilament networks and – ultimately - denervation of neuromuscular junctions [3, 4]. A recent study proposed that APP actively contributes to the neuronal pathology in certain forms of ALS [5]. Here, we provide evidence that the proteolytic processing and intraneuronal localization of APP-derived fragments depend on intact peripherin-containing neurofilaments present in the soma. These results point to a possible crosstalk between the molecular machineries involved in the pathogenesis of AD and ALS.

Methods

In this study, we employed CAD neuronal cells [6–8], a brainstem derived, neuronal cell line that, similar to the motor neurons, expresses peripherin. CAD neuronal cells also express APP, which is processed by secretases to generate the characteristic proteolytic fragments that are relevant to AD: sAPPβ, CTFβ, Aβ, and AICD [9–11] (fig.1a). Immunocytochemistry, immunoblotting, and transfection with peripherin siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) plus GFP (to visualize transfected cells) were carried out as described [12, 13]. The antibodies recognizing epitopes from the N-(22C11) or C- (AB5352) terminal region of APP were from Millipore. Previous work indicated that, in CAD neuronal cells, the antibody 22C11 largely detects sAPP, rather than full-length APP [9]. The anti-peripherin antibody was kindly provided by Dr. Robert Goldman (Northwestern University).

Figure 1.

Segregated distribution of APP-derived polypeptides. a Diagram showing the polypeptide fragments resulting from the cleavage of APP by β- and γ-secretase. Cleavage by β-secretase produces NTFβ (also referred to as sAPPβ) and CTFβ. Aβ and the APP intracellular domain (AICD) are obtained from CTFβ by cleavage by γ-secretase. The dotted lines mark the transmembrane domain. b Antibodies recognizing the N- (APPN), but not C-terminal (APPC) epitopes of APP label a filamentous, perinuclear compartment in the soma of CAD neuronal cells. Bar = 20 µm.

Results

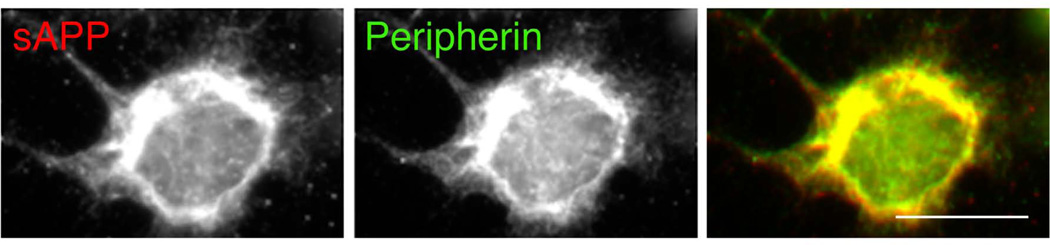

Our previous studies with cultured neurons and mouse brain in situ have shown that a significant fraction of APP is proteolytically cleaved by secretases in the neuronal soma, leading to the generation of N- and C-terminal fragments (sAPP and CTFs; fig. 1a) that are targeted to distinct neuronal compartments [9]. Immunocytochemistry with antibodies that detect epitopes within the N- and C-terminal regions of APP showed largely nonoverlapping distributions, with the antibodies to N- but not C-terminal epitopes labeling a network of tubular structures surrounding the nucleus (fig. 1b). These results indicate that, in these conditions, the antibodies to N-terminal epitopes largely reveal sAPP, not full-length APP. The immunolabeling pattern of sAPP was reminiscent of the cytoskeletal neurofilament network, which is tightly associated with the nuclear envelope. With dual immunolabeling, we showed that the sAPP detected in the soma displays strong colocalization with peripherin (fig. 2), a subunit of neurofilaments expressed in the adult neurons of the peripheral nervous system and the brainstem [14]. We note that colocalization of APP with cytoskeletal filaments that are not microtubules was previously detected in glial cells [15].

Figure 2.

The APP N-terminal epitopes detected with antibody 22C11 (likely sAPP) colocalize with the peripherin-positive neurofilaments in a region surrounding the nucleus of CAD neuronal cells. Bar = 20 µm.

To examine the link between the distribution of sAPP and that of neurofilaments, we tested whether the depletion of peripherin protein affects the distribution of sAPP. Although neurofilament proteins are long-lived, CAD neuronal cells showed significantly diminished peripherin levels four days after transfection with peripherin siRNA (fig. 3). Cells with reduced peripherin levels, visualized by the cotransfected GFP, lacked perinuclear peripherin, and no longer showed the filamentous, perinuclear distribution of sAPP evident in nontransfected cells (fig. 3). This result indicates that the presence of neurofilaments is required for either the generation of sAPP from full-length APP, or for the localization of sAPP-containing membrane vesicles along neurofilaments. Thus, this work uncovers a functional interaction between APP and peripherin neurofilaments in CAD neuronal cells.

Figure 3.

Silencing the expression of prph by transfection of CAD neuronal cells with peripherin siRNA diminishes the expression of peripherin protein with over 50% (immunoblot, top right; the Ponceau S stained transfers at bottom right show comparable loads in siRNA-treated and control cells) and abrogates the characteristic, perinuclear localization of both peripherin and sAPP (immunofluorescence images). Cotransfected GFP marks the siRNA treated cells (left and middle images). A nontransfected, control cell is shown for comparison (right images). For increased resolution of sAPP labeling, the top images are shown in black and white. Bars = 20 µm. Molecular weight markers are in kilodaltons.

Conclusions

This study identifies the neurofilament protein, peripherin as a potential regulator of APP metabolism and trafficking in neurons. One possibility is that the proteolytic processing of APP occurs in a compartment – endosomes, or part of the endoplasmic reticulum [16] - associated with the neurofilament cytoskeleton. Alternatively, the neurofilaments could play a role in the segregation of the sAPP from CTF, once they have been generated in a somatic compartment, by selectively anchoring, and concentrating sAPP-containing vesicles in the perinuclear region. This region has been recently shown to be a site for accumulation of APP-derived polypeptides, with relevance to AD [17]. Interestingly, ALS-specific mutations in the peripherin gene [18, 19] lead to abnormal neurofilament organization (reviewed in [20]). In principle, these cytoskeletal changes could cause abnormal processing – and thus altered function - of APP, a possibility supported by our results. We propose that this functional interaction between APP and peripherin neurofilaments may provide the basis for crosstalk between the molecular mechanisms of disease in AD and ALS.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health award AG039668 (Z.M.) and New Jersey Health Foundation grants (Z.M., V.M.).

References

- 1.Muresan V, Muresan Z. Is abnormal axonal transport a cause, a contributing factor or a consequence of the neuronal pathology in alzheimer's disease? Future Neurology. 2009;4:761–773. doi: 10.2217/fnl.09.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng H, Koo EH. Biology and pathophysiology of the amyloid precursor protein. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wijesekera LC, Leigh PN. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao S, McLean J, Robertson J. Neuronal intermediate filaments and ALS: A new look at an old question. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1762:1001–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryson JB, Hobbs C, Parsons MJ, Bosch KD, Pandraud A, Walsh FS, Doherty P, Greensmith L. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) contributes to pathology in the SOD1(G93A) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3871–3882. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muresan Z, Muresan V. Seeding neuritic plaques from the distance: A possible role for brainstem neurons in the development of Alzheimer's disease pathology. Neurodegener Dis. 2008;5:250–253. doi: 10.1159/000113716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muresan Z, Muresan V. SWAN Alzheimer Knowledge Base. Alzheimer Research Forum. 2009. CAD cells are a useful model for studies of APP cell biology and Alzheimer’s disease pathology, including accumulation of Aβ within neurites. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qi Y, Wang JK, McMillian M, Chikaraishi DM. Characterization of a CNS cell line, CAD, in which morphological differentiation is initiated by serum deprivation. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1217–1225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01217.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muresan V, Varvel NH, Lamb BT, Muresan Z. The cleavage products of amyloid-β precursor protein are sorted to distinct carrier vesicles that are independently transported within neurites. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3565–3578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2558-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muresan Z, Muresan V. A phosphorylated, carboxy-terminal fragment of β-amyloid precursor protein localizes to the splicing factor compartment. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:475–488. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muresan Z, Muresan V. Neuritic deposits of amyloid-β peptide in a subpopulation of central nervous system-derived neuronal cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4982–4997. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00371-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muresan Z, Muresan V. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-interacting protein-3 facilitates phosphorylation and controls localization of amyloid-β precursor protein. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3741–3751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0152-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muresan Z, Muresan V. Coordinated transport of phosphorylated amyloid-β precursor protein and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-interacting protein-1. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:615–625. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan A, Sasaki T, Kumar A, Peterhoff CM, Rao MV, Liem RK, Julien JP, Nixon RA. Peripherin is a subunit of peripheral nerve neurofilaments: Implications for differential vulnerability of CNS and peripheral nervous system axons. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8501–8508. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1081-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berkenbosch F, Refolo LM, Friedrich VL, Jr, Casper D, Blum M, Robakis NK. The Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein is produced by type I astrocytes in primary cultures of rat neuroglia. J Neurosci Res. 1990;25:431–440. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490250321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muresan V, Muresan Z. A persistent stress response to impeded axonal transport leads to accumulation of amyloid-β in the endoplasmic reticulum, and is a probable cause of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;10:60–63. doi: 10.1159/000332815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glabe C. Conformational diversity of amyloid in human ad brain. The 11th International Conference on Alzheimer's & Parkinson's Disease, Florence, Italy; March 6–10 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corrado L, Carlomagno Y, Falasco L, Mellone S, Godi M, Cova E, Cereda C, Testa L, Mazzini L, D'Alfonso S. A novel peripherin gene (PRPH) mutation identified in one sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:552, e551–e556. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung CL, He CZ, Kaufmann P, Chin SS, Naini A, Liem RK, Mitsumoto H, Hays AP. A pathogenic peripherin gene mutation in a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:290–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millecamps S, Julien JP. Axonal transport deficits and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:161–176. doi: 10.1038/nrn3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]