Abstract

While the ability of blood vessels to carry fluid and cells through neoplastic tissue is clearly important, other functions of vascular elements that drive tumor growth and progression are increasingly being recognized. Vessels can provide physical support and help regulate the stromal microenvironment within tumors, form niches for tumor associated stem cells, serve as avenues for local tumor spread, and promote relative immune privilege. Understanding the molecular drivers of these phenotypes will be critical if we are to therapeutically target their protumorigenic effects. The potential for neoplastic cells to transdifferentiate into vascular and perivascular elements also needs to be better understood, as it has the potential to complicate such therapies. In this review, we provide a brief overview of these less conventional vascular functions in tumors.

Background

For many years, the study of vascular biology focused primarily on delivery of cells, nutrients and oxygen to tissues of the body. These functions are also critical in neoplastic growth, and the ability to expand their circulatory network through angiogenesis or vasculogenesis is a fundamental process shared by many tumors. Early investigators such as Judah Folkman noted that most solid neoplasms which were not able to promote an angiogenic response stopped growing when they reached 2 to 3 mm in size, and attributed this finding to limitations of oxygen and nutrient diffusion (1). Subsequent studies confirmed that the degree of microvascular proliferation can show a significant correlation with aggressive behavior in many cancers, including those arising in the breast, lung, and colon (2-4). However, it has become clear that tumor-promoting effects of the vasculature are not restricted to simple transport functions.

As neuropathologists, we have been amazed by the varied appearance of abnormal neovascular structures in brain tumors; they range from elongated vascular festoons to compact “glomeruloid” snarls visually similar to the filtration units of kidneys. Indeed, the angiogenic process in some brain tumors is so pathologically important that it has been formally incorporated into tumor classification and grading, with the presence of aberrant microvascular structures sufficient to discriminate between a WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytoma and a WHO grade IV glioblastoma (5). However, these prognostically critical vessels often feature poorly structured lumens and a paucity of red blood cells, suggesting that they may not be effective in tissue oxygenation. Indeed, it is now known that many neoplasms are less dependent than normal tissues on an oxygen-rich microenvironment, and may in fact thrive in low oxygen due to effects of Hypoxia Inducible Factor (HIF) and other mediators on tumor metabolism, stem cell and invasive properties, and therapeutic resistance (6). Thus in some cases, the delivery functions of vessels within tumors may be secondary to alternative roles.

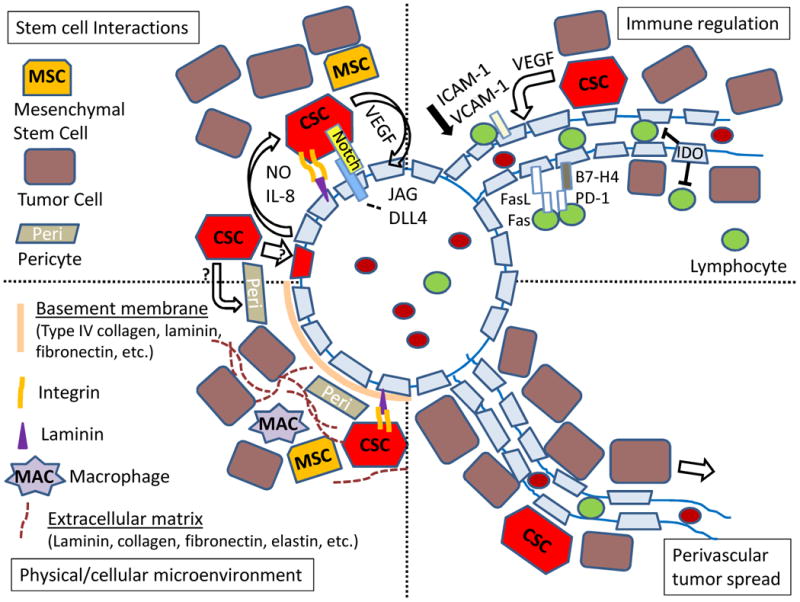

This brief review outlines some of the ways vessels can contribute to neoplastic growth independent of their role as fluid conduits, including: (1) providing physical support or regulating stromal function within tumors, (2) providing a niche for tumor associated stem cells, (3) as an avenue for tumor spread and metastasis, and (4) promoting relative immune privilege within the tumor (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Non-Transport Functions of Tumor Associated Blood Vessels.

The vasculature within tumors can affect the physical and cellular microenvironment, which in turn modulates cancer stem cells (CSC), immune function and local spread of neoplastic cells. The endothelium, perivascular basement membrane and associated extracellular matrix (ECM) play key roles in this process. Control of CSC can occur via direct binding of laminin and Notch ligands on the endothelial surface or release of factors such as nitric oxide (NO) or IL-8. Immune function regulation includes a range of endothelial signals, including FasL, B7-H4, IDO, and adhesion molecules. Finally, in tumors such as melanoma and glioma the vessels serve as a path for local invasion.

Regulation of physical properties and extracellular matrix by blood vessels

The branched network of blood vessels coursing through both normal and neoplastic tissues help to define overall physical structure, and often at the same time regulate properties of surrounding cells. In normal organs, vascular development can play a key role in tissue patterning. For example, in the fetal pancreas blood vessels are required for endocrine specification at the time of pancreatic budding, while later in development they suppress branching of the organ (7). In tumors, the vasculature also serves complex and changing roles that affect both physical structure and the signaling properties of neoplastic stroma. Physical and functional vascular changes commonly seen within malignancies include irregular architecture and tortuosity, slow flow, increased fenestration and permeability, altered basement membranes and pericytes, and surrounding fibrosis/desmoplasia (8).

One way that the dense, abnormal blood vessels within neoplastic tissues regulate local microenvironment is through interactions with the extracellular matrix (ECM). ECM is composed of protein fibers interwoven with laminins, collagens, fibronectin and other more specialized elements (9). Endothelial cells tightly adhere to a basement membrane containing type IV collagen and other elements which contact the ECM. Focal adhesions – intercellular complexes linking the endothelial cytoskeleton with ECM factors – represent one structure allowing the microvasculature and surrounding stroma to directly influence one another via signaling through transmembrane receptors, integrins, focal adhesion kinase (FAK), or other transduction cascades (10). The effects of integrins and other ECM components on the proliferation, survival, differentiation and migration of a range of cancers are well known (9, 11).

In addition to these signal transduction cascades, purely mechanical features of the ECM are also increasingly being recognized as important modulators of both vascular and tumor biology (12, 13). For example, breast cancer progression is associated with increased ECM stiffness, and tumor growth can be modulated by increasing or decreasing ECM cross linking in vivo (14, 15). Pharmacological inhibition of LOX in the MMTV-Neu murine breast cancer model resulted in significant decreases in collagen crosslinks, a reduction in tumor incidence by approximately one third, and an over 70% (p < 0.05) decrease in the size of lesions which formed (15). Such phenomena may be caused in part by mechanosensitive mechanisms regulating transcription in both tumor cells and endothelium (12, 16). In turn, angiogenesis can be controlled by physical interactions with the extracellular matrix (16). Thus tumor vasculature can regulate neoplastic growth both through mechanical effects on the physical structure of tissue and changes to the local microenvironment which alter its signaling properties.

Blood vessels as a stem cell niche

The perivascular stem cell niche represents an example of how integrated structural and signaling cues from vessels affect tumor biology. The cancer stem cell (CSC) hypothesis postulates a hierarchical organization of tumor cell proliferation and differentiation, with stem-like cells capable of initiating xenografts and propagating long term neoplastic growth representing a small proportion of the lesion. The clinical importance of CSC is highlighted by their propensity to show relative resistance to chemotherapy and radiation (17, 18), and it has been suggested that the presence of tumor vasculature can modulate these effects. Hovinga and colleagues compared the radiation response of GBM tissue explants to that of dissociated neurosphere cultures comprised of only neoplastic cells, and found a statistically significant 10-fold reduction of clonogenicity after radiation in pure tumor cells, but no significant decrease (p = 0.45) in the presence of stroma, a difference they felt was due predominantly to endothelial cells and other vascular elements in the explants (19).

Like non-neoplastic stem cells, CSC are thought to derive critical support from specific “niche” microenvironments. In many tumors, CSC niches have been demonstrated in perivascular regions, with robust crosstalk between the CSCs and vascular elements. In addition to supporting neoplastic stem cells, blood vessels can also nurture mesenchymal stem cells (MSC), macrophages and other cellular elements which modulate the surrounding microenvironment and effect tumor growth (20, 21). Endothelial cells are an important source of trophic factors for the CSC niche. Inclusion of vascular endothelial cells in medulloblastoma xenografts increased the stem-like fraction up to 25-fold, and also increased tumor size such that animals succumbed to disease burden after 4 weeks rather than 7 (22). In contrast, antiangiogenic therapy decreased tumor size by over 90% in GBM xenografts (p < 0.001), and targeted ablation of the vasculature in head and neck carcinoma xenografts caused an approximately 50% reduction in CSC numbers (p < 0.005) (23, 24). A wide range of molecular factors have been implicated in signaling from niche cells to CSC, including interleukin-8, laminins, notch ligands and nitric oxide, with many of these representing potential therapeutic targets expressed on the surface of normal and tumor-associated vasculature (19, 25-29).

One interesting feature of the interactions between tumor and vessels is the role played by neoplastic cells in promoting their own perivascular CSC niche. VEGF derived from tumor cells appears to be critical in activating a diverse set of signaling pathways in endothelial cells that maintain the CSC niche and support tumor growth. In mouse models of squamous papilloma and carcinoma, the vascular CSC niche is dependent on VEGF signaling through the nrp-1 co-receptor on endothelial cells, and the loss of VEGF receptors resulted in almost complete regression of tumors within two weeks (p < 0.0001) (30).

VEGF can also modulate critical developmental pathways that are exploited by CSCs. For instance, in models of T lymphoblastic leukemia, VEGF results in upregulation of the Notch ligand DLL4 (31). The resultant signaling through Notch3 reduces apoptosis and promotes proliferation of leukemic cells. An analogous relationship between vascular DLL4 expression and Notch signaling has been established in both colon cancer and glioblastoma (28, 32). Yen and colleagues showed that DLL4 blocking antibodies could reduce the size of a panel of pancreatic carcinoma xenografts by 27-53% (p < 0.01), and using human and murine specific anti-DLL4 blocking antibodies found that effects on both tumor cells and stromal vessels played a role in these effects (33). VEGF also is able to modulate Notch signaling through non-canonical pathway activation. VEGF signaling upregulates endothelial cell nitric oxide synathase (eNOS). The resultant NO production in endothelial cells promotes Notch signaling in glioma stem cells through a cGMP/PKG dependent mechanism (29). A similar mechanism may exist for leukemic stem cells as VEGF-stimulated NO production supports growth of leukemia cell lines in vitro (34).

Blood vessels and tumor dissemination

It is often the ability of tumor cells to either vigorously invade locally or metastasize to distant sites which leads to patient death. The pivotal role of arteries, veins and lymphatics as highways for metastatic dissemination is clear. Indeed, the impact of vascular structures on metastatic spread is now known to extend even further that previously recognized, with the perivascular niche shown to regulate dormancy of breast cancer metastases after they exit vessel lumens. In a recent study using murine xenograft models, Ghajar and colleagues found that metastatic breast cancer cells adjacent to mature vessels were kept dormant by endothelial-derived thrombospondin-1, but as new vessels sprouted this inhibitory signal was lost and metastases grew (35).

Another important but less studied role that blood vessels play in tumor dissemination is as a scaffold for direct invasion of the neoplasm into adjacent tissues. Infiltrating gliomas have long been known to show a propensity for extension along blood vessels (5), and this feature is particularly prominent in a number of neurosphere-based xenograft models that we and other investigators have developed. Interestingly, while gliomas are frequently found extending along the outside of vessels, they almost never invade into their lumens or spread hematogenously. Extension along vessels has also been noted in other types of cancer, including head and neck carcinoma and melanoma (36, 37). For some tumors such as angiocentric glioma and angiocentric T cell lymphoma, perivascular growth is so intrinsic to the basic biology of the lesion that it is reflected in their name.

Angiotropic spread in melanoma has been termed “extravascular migratory metastasis”, and is associated with both diffuse local invasion and eventual distant metastatic spread (38, 39). The molecular mechanisms associated with perivascular tumor spread are beginning to be elucidated. UV radiation and laminin peptides have both been shown to promote growth of cutaneous melanoma along the outside of blood vessels (40, 41). In gliomas, upregulation of integrins, dystroglycans and syndecan by tumor cells may facilitate their movement along the vascular basement membrane (42). Finally, expression of EMMPRIN, a transmembrane glycoprotein, is positively correlated with perivascular invasion of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma (43). These examples suggest that the role of vessels as highways for local spread bears more investigation, and may represent a novel point of therapeutic intervention.

Tumor vessels and immune privilege

The signals that stimulate angiogenesis seem to directly promote a relatively immunosuppressed local microenvironment. Much of this immunosuppression is through signaling of proangiogenic factors such as VEGF to immune effector cells including lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (44). However, endothelial cells may also contribute directly to immune privilege by modulating the quantity and quality of immune cells trafficking into tumors or by inhibition of effector T cells.

Immune cell trafficking requires the binding of cell adhesion molecules including ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on the surface of endothelial cells by LFA-1 and VLA-1 on immune effector cells. The quantity of trafficking lymphocytes is reduced following downregulation of cell adhesion molecules, and reduced expression of ICAM-1 or VCAM-1 on intratumoral endothelial cells has been reported for a number different cancers including renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and small cell lung cancer (45, 46). Tumors may also modulate the efficacy of cell adhesion molecule binding on vessels. For instance, tumor derived VEGF has been shown to reduce effective clustering of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on the surface of endothelial cells in a nitric oxide dependent manner (47). Alternatively, endothelial cells may instead regulate the quality of the immune cells trafficking to tumors. For instance, upregulation of vascular addressins in pancreatic cancer leads to selective recruitment of immunosuppressive CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (48).

Tumor cells are known to directly inhibit lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation through a variety of mechanisms; however, evidence suggests that intratumoral endothelial cells express many of the same immunosuppressive mediators. For instance, expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) has been reported in the endothelial cells of renal cell carcinoma (49), and is thought to inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by depletion of local tryptophan pools (50). Tumor endothelial cells may also inhibit lymphocyte activity through expression of immunosuppressive receptors. Expression of B7-H4, a repressive co-receptor, has been reported in renal cell carcinoma (51) and the expression of FasL on the surface of endothelial cells may contribute to the immune privilege of gliomas (52). It is unclear if neovasculature demonstrates a greater propensity to utilize these immunosuppressive mechanisms compared to native vessels.

Clinical-Translational Advances

Targeting vascular growth and the perivascular microenvironment

One way to ameliorate the tumorigenic properties of blood vessels is to directly target the factors promoting neovascular proliferation. The best studied approach is inhibition of VEGF, and as noted above it has been shown that this anti-angiogenic treatment can have pronounced effects on CSC numbers. Antibodies targeting VEGF such as Bevicizumab and Ramucirumab have been approved for use in a range of solid tumors, with additional trials ongoing. Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as Apatinib are also used to block VEGF receptors, with many of these (Cabozantinib, Pazopanib, Axitinib, Sunitinib) also affecting additional angiogenic receptors such the platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR). Other targets such as the Angiopoetin-Tie2 axis, Placental growth factor (PlGF) and the Notch pathway are also increasingly being studied (53). One postulated benefit of these and analogous targeted therapies is “normalization” of the vasculature, which can allow standard chemotherapies to function more effectively, as well as potentially reducing some of the changes to the perivascular microenvironment that favor neoplastic growth (53, 54).

Many individual molecular components present in endothelial cells and the perivascular tumor microenvironment also represent promising targets. Notch ligands are critical modulators of abnormal neovascularization within tumors, and represent well characterized signals from the perivascular niche to CSC. It is therefore not surprising that a range of therapies targeting Notch are being developed, including small molecules which block receptor cleavage and activation such as MK-0572, BMS-906024, BMS-986115, RO4929097, and PF-030841014, which have all been evaluated in clinical trials. Additional methods of Notch suppression include inhibitory antibodies targeting individual receptors and ligands, and stapled blocking peptides that interfere with transcriptional activation in the nucleus (19, 28, 31, 32, 55). Nitric oxide production by endothelium, which activates Notch and other protumorigenic pathways, represents another potential point of intervention but has largely been evaluated in the preclinical setting for cancer (29, 56).

The interactions between integrins, vascular cells, ECM and tumor cells can be targeted using a range of agents, the majority of which affect RGD-binding integrins (57). Cilengitide, a cyclic RGD pentapeptide, has been shown to affect angiogenesis and invasion in xenograft models, but was not effective in a recent phase III trial in GBM patients (58, 59). Functional connections between vascular endothelium and ECM are also mediated by focal adhesions, and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) represents a therapeutic target which can be directly targeted with FAK-inhibitors such as Defactinib and VS-4718, or modulated indirectly by statins, FTY720, SKI-606 and other agents (10). Given the complex interactions between the various neoplastic and non-neoplastic cell types in the perivascular space, these represent only a small portion of the potential treatments, and understanding how to best combine such therapies with other agents targeting tumor cells will be challenging.

Will neoplastic vasculature complicate therapies?

Most therapeutic options discussed above have historically been predicated on the notion that tumor-associated vessels lack the genetic alterations and instability found in neoplastic cells, which can lead to therapeutic resistance. Recently, however, several studies have suggested that glial tumors may contribute to their vascular supply and perivascular microenvironment by transdifferentiation into endothelial cells (60-62). Vasculogenic mimicry is another example of tumor cells forming vascular tubes, but without taking on an endothelial phenotype. While the profound plasticity of CSC is intriguing, in our clinical experience genetically altered tumor cells make up little or none of the vascular endothelium in brain tumors analyzed using diagnostic molecular markers such as mutant IDH1 immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization for EGFR or PDGFR receptor amplification (63). Cheng and colleagues also failed to identify a significant neoplastic contribution to vascular endothelium, but found transdifferentiation of glioma cells into pericytes in animal models and human tumor specimens (64). While these studies provide some clinical information for glioblastoma patients, for most tumor types it is unclear to what extent neoplastic transdifferentiation contributes to new vessel formation, and this will need to be studied and possibly taken into account as therapeutic interventions are planned.

In conclusion, it has long been recognized that the growth of new blood vessels is a hallmark of cancer, but also that such neovascular proliferations can appear quite different from vessels associated with non-neoplastic tissues. The abnormal vascular profiles within tumors often seem ill suited for efficient delivery of blood, and a range of molecular and functional studies are beginning to reveal novel roles played by these vessels in establishing specific perivascular microenvironments which can promote immune suppression and local tumor spread, as well as treatment resistance and the growth of stem-like populations of tumor cells. Therapeutically targeting such functions may represent an exciting new component of multipronged treatments for cancer, but the ability of neoplastic cells to directly or indirectly contribute to vessels may need to be taken into account.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under award number R01NS055089 to C.G. Eberhart. B.A. Orr has received support from the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: C.G. Eberhart reports receiving royalties, through his institution, for intellectual property related to certain gamma-secretase inhibitors targeting Notch that is owned by Johns Hopkins University and licensed to Stemline Therapeutics, Inc. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other author.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. New Engl J Med. 1971;285:1182–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meert AP, Paesmans M, Martin B, Delmotte P, Berghmans T, Verdebout JM, et al. The role of microvessel density on the survival of patients with lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:694–701. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Des Guetz G, Uzzan B, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, Morere JF, Benamouzig R, et al. Microvessel density and VEGF expression are prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. Meta-analysis of the literature. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1823–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uzzan B, Nicolas P, Cucherat M, Perret GY. Microvessel density as a prognostic factor in women with breast cancer: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2941–55. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. LYON: IARC Press; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors: mediators of cancer progression and targets for cancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villasenor A, Cleaver O. Crosstalk between the developing pancreas and its blood vessels: an evolving dialog. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:685–92. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seo BR, Delnero P, Fischbach C. In vitro models of tumor vessels and matrix: Engineering approaches to investigate transport limitations and drug delivery in cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;69-70:205–16. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kostourou V, Papalazarou V. Non-collagenous ECM proteins in blood vessel morphogenesis and cancer. Biochimi Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:2403–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Infusino GA, Jacobson JR. Endothelial FAK as a therapeutic target in disease. Microvascular Res. 2012;83:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:395–406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mammoto A, Mammoto T, Ingber DE. Mechanosensitive mechanisms in transcriptional regulation. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3061–73. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu WF. Mechanical regulation of cellular phenotype: implications for vascular tissue regeneration. Cardiovascular Res. 2012;95:215–22. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Werfel J, Krause S, Bischof AG, Mannix RJ, Tobin H, Bar-Yam Y, et al. How changes in extracellular matrix mechanics and gene expression variability might combine to drive cancer progression. PloS One. 2013;8:e76122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mammoto A, Connor KM, Mammoto T, Yung CW, Huh D, Aderman CM, et al. A mechanosensitive transcriptional mechanism that controls angiogenesis. Nature. 2009;457:1103–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rich JN. Cancer stem cells in radiation resistance. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8980–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basile KJ, Aplin AE. Resistance to chemotherapy: short-term drug tolerance and stem cell-like subpopulations. Adv Pharmacol. 2012;65:315–34. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397927-8.00010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hovinga KE, Shimizu F, Wang R, Panagiotakos G, Van Der Heijden M, Moayedpardazi H, et al. Inhibition of notch signaling in glioblastoma targets cancer stem cells via an endothelial cell intermediate. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1019–29. doi: 10.1002/stem.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hass R, Otte A. Mesenchymal stem cells as all-round supporters in a normal and neoplastic microenvironment. Cell Commun Signal. 2012;10:26. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barcellos-de-Souza P, Gori V, Bambi F, Chiarugi P. Tumor microenvironment: bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cells as key players. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1836:321–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, Hogg TL, Fuller C, Hamner B, et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsumetee S, Hao Y, Li Z, Hjelmeland AB, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7843–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishnamurthy S, Dong Z, Vodopyanov D, Imai A, Helman JI, Prince ME, et al. Endothelial cell-initiated signaling promotes the survival and self-renewal of cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9969–78. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Infanger DW, Cho Y, Lopez BS, Mohanan S, Liu SC, Gursel D, et al. Glioblastoma stem cells are regulated by interleukin-8 signaling in a tumoral perivascular niche. Cancer Res. 2013;73:7079–89. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lathia JD, Li M, Hall PE, Gallagher J, Hale JS, Wu Q, et al. Laminin alpha 2 enables glioblastoma stem cell growth. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:766–78. doi: 10.1002/ana.23674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu J, Ye X, Fan F, Xia L, Bhattacharya R, Bellister S, et al. Endothelial cells promote the colorectal cancer stem cell phenotype through a soluble form of Jagged-1. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:171–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu TS, Costello MA, Talsma CE, Flack CG, Crowley JG, Hamm LL, et al. Endothelial cells create a stem cell niche in glioblastoma by providing NOTCH ligands that nurture self-renewal of cancer stem-like cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6061–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charles N, Ozawa T, Squatrito M, Bleau AM, Brennan CW, Hambardzumyan D, et al. Perivascular nitric oxide activates notch signaling and promotes stem-like character in PDGF-induced glioma cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:141–52. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck B, Driessens G, Goossens S, Youssef KK, Kuchnio A, Caauwe A, et al. A vascular niche and a VEGF-Nrp1 loop regulate the initiation and stemness of skin tumours. Nature. 2011;478:399–403. doi: 10.1038/nature10525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Indraccolo S, Minuzzo S, Masiero M, Pusceddu I, Persano L, Moserle L, et al. Cross-talk between tumor and endothelial cells involving the Notch3-Dll4 interaction marks escape from tumor dormancy. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1314–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer M, Yen WC, Kapoun AM, Wang M, O'Young G, Lewicki J, et al. Anti-DLL4 inhibits growth and reduces tumor-initiating cell frequency in colorectal tumors with oncogenic KRAS mutations. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1520–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yen WC, Fischer MM, Hynes M, Wu J, Kim E, Beviglia L, et al. Anti-DLL4 has broad spectrum activity in pancreatic cancer dependent on targeting DLL4-Notch signaling in both tumor and vasculature cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5374–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koistinen P, Siitonen T, Mantymaa P, Saily M, Kinnula V, Savolainen ER, et al. Regulation of the acute myeloid leukemia cell line OCI/AML-2 by endothelial nitric oxide synthase under the control of a vascular endothelial growth factor signaling system. Leukemia. 2001;15:1433–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghajar CM, Peinado H, Mori H, Matei IR, Evason KJ, Brazier H, et al. The perivascular niche regulates breast tumour dormancy. Nature Cell Biol. 2013;15:807–17. doi: 10.1038/ncb2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le Tourneau C, Jung GM, Borel C, Bronner G, Flesch H, Velten M. Prognostic factors of survival in head and neck cancer patients treated with surgery and postoperative radiation therapy. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:706–12. doi: 10.1080/00016480701675668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lugassy C, Vernon SE, Busam K, Engbring JA, Welch DR, Poulos EG, et al. Angiotropism of human melanoma: studies involving in transit and other cutaneous metastases and the chicken chorioallantoic membrane: implications for extravascular melanoma invasion and metastasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:187–93. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200606000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnhill R, Dy K, Lugassy C. Angiotropism in cutaneous melanoma: a prognostic factor strongly predicting risk for metastasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:705–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lugassy C, Haroun RI, Brem H, Tyler BM, Jones RV, Fernandez PM, et al. Pericytic-like angiotropism of glioma and melanoma cells. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:473–8. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200212000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bald T, Quast T, Landsberg J, Rogava M, Glodde N, Lopez-Ramos D, et al. Ultraviolet-radiation-induced inflammation promotes angiotropism and metastasis in melanoma. Nature. 2014;507:109–13. doi: 10.1038/nature13111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lugassy C, Kleinman HK, Vernon SE, Welch DR, Barnhill RL. C16 laminin peptide increases angiotropic extravascular migration of human melanoma cells in a shell-less chick chorioallantoic membrane assay. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:780–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gritsenko PG, Ilina O, Friedl P. Interstitial guidance of cancer invasion. J Pathol. 2012;226:185–99. doi: 10.1002/path.3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang X, Zhang P, Ma Q, Kong L, Li Y, Liu B, et al. EMMPRIN silencing inhibits proliferation and perineural invasion of human salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Biol Ther. 2012;13:85–91. doi: 10.4161/cbt.13.2.18455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Motz GT, Coukos G. The parallel lives of angiogenesis and immunosuppression: cancer and other tales. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:702–11. doi: 10.1038/nri3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griffioen AW, Damen CA, Martinotti S, Blijham GH, Groenewegen G. Endothelial intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression is suppressed in human malignancies: the role of angiogenic factors. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1111–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piali L, Fichtel A, Terpe HJ, Imhof BA, Gisler RH. Endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 expression is suppressed by melanoma and carcinoma. J Exp Med. 1995;181:811–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bouzin C, Brouet A, De Vriese J, Dewever J, Feron O. Effects of vascular endothelial growth factor on the lymphocyte-endothelium interactions: identification of caveolin-1 and nitric oxide as control points of endothelial cell anergy. J Immunol. 2007;178:1505–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nummer D, Suri-Payer E, Schmitz-Winnenthal H, Bonertz A, Galindo L, Antolovich D, et al. Role of tumor endothelium in CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell infiltration of human pancreatic carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1188–99. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riesenberg R, Weiler C, Spring O, Eder M, Buchner A, Popp T, et al. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in tumor endothelial cells correlates with long-term survival of patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Res. 2007;13:6993–7002. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uyttenhove C, Pilotte L, Theate I, Stroobant V, Colau D, Parmentier N, et al. Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Nat Med. 2003;9:1269–74. doi: 10.1038/nm934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krambeck AE, Thompson RH, Dong H, Lohse CM, Park ES, Kuntz SM, et al. B7-H4 expression in renal cell carcinoma and tumor vasculature: associations with cancer progression and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10391–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600937103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu JS, Lee PK, Ehtesham M, Samoto K, Black KL, Wheeler CJ. Intratumoral T cell subset ratios and Fas ligand expression on brain tumor endothelium. J Neurooncol. 2003;64:55–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02700020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goel S, Wong AH, Jain RK. Vascular normalization as a therapeutic strategy for malignant and nonmalignant disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006486. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang Y, Goel S, Duda DG, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Vascular normalization as an emerging strategy to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2943–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Espinoza I, Miele L. Notch inhibitors for cancer treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;139:95–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Choudhari SK, Chaudhary M, Bagde S, Gadbail AR, Joshi V. Nitric oxide and cancer: a review. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:118. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodman SL, Picard M. Integrins as therapeutic targets. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:405–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishida J, Onishi M, Kurozumi K, Ichikawa T, Fujii K, Shimazu Y, et al. Integrin Inhibitor Suppresses Bevacizumab-Induced Glioma Invasion. Transl Oncol. 2014;7:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Onishi M, Ichikawa T, Kurozumi K, Fujii K, Yoshida K, Inoue S, et al. Bimodal anti-glioma mechanisms of cilengitide demonstrated by novel invasive glioma models. Neuropathology. 2013;33:162–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2012.01344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang R, Chadalavada K, Wilshire J, Kowalik U, Hovinga KE, Geber A, et al. Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour endothelium. Nature. 2010;468:829–33. doi: 10.1038/nature09624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ricci-Vitiani L, Pallini R, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Invernici G, Cenci T, et al. Tumour vascularization via endothelial differentiation of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Nature. 2010;468:824–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Soda Y, Marumoto T, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Soda M, Liu F, Michiue H, et al. Transdifferentiation of glioblastoma cells into vascular endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4274–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodriguez FJ, Orr BA, Ligon KL, Eberhart CG. Neoplastic cells are a rare component in human glioblastoma microvasculature. Oncotarget. 2012;3:98–106. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cheng L, Huang Z, Zhou W, Wu Q, Donnola S, Liu JK, et al. Glioblastoma stem cells generate vascular pericytes to support vessel function and tumor growth. Cell. 2013;153:139–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]