Summary

Background

Filamentous fungi and bacteria form mixed-species biofilms in nature and diverse clinical contexts. They secrete a wealth of redox-active small molecule secondary metabolites, which are traditionally viewed as toxins that inhibit growth of competing microbes.

Results

Here we report that these “toxins” can act as interspecies signals, affecting filamentous fungal development via oxidative stress regulation. Specifically, in co-culture biofilms, Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazine-derived metabolites differentially modulated Aspergillus fumigatus development, shifting from weak vegetative growth to induced asexual sporulation (conidiation) along a decreasing phenazine gradient. The A. fumigatus morphological shift correlated with the production of phenazine radicals and concomitant reactive oxygen species (ROS) production generated by phenazine redox cycling. Phenazine conidiation signaling was conserved in the genetic model A. nidulans, and mediated by NapA, a homolog of AP-1-like bZIP transcription factor, which is essential for the response to oxidative stress in humans, yeast, and filamentous fungi. Expression profiling showed phenazine treatment induced a NapA-dependent response of the global oxidative stress metabolome including the thioredoxin, glutathione and NADPH-oxidase systems. Conidiation induction in A. nidulans by another microbial redox-active secondary metabolite, gliotoxin, also required NapA.

Conclusions

This work highlights that microbial redox metabolites are key signals for sporulation in filamentous fungi, which are communicated through an evolutionarily conserved eukaryotic stress response pathway. It provides a foundation for interspecies signaling in environmental and clinical biofilms involving bacteria and filamentous fungi.

Introduction

In the human body, the majority of microbial infections are biofilm-associated. Many biofilms involve mixed-species of bacteria and fungi, co-colonizing surfaces of tissues and implants [1–2]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common Gram-negative bacterium, whose biofilm lifestyle is at the root of many persistent and chronic infections [3]. The filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus is the most prevalent airborne fungal pathogen, and the main causative agent for life-threatening invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients [4]. P. aeruginosa, A. fumigatus, and non-fumigatus Aspergillus are often found to co-colonize the lungs of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients, open skin wounds in burn patients, and cardiac implants [1–2] and models to assess co-culture biofilm for these two microbes have been described [5]. How they interact with each other can determine the structure of the microbial community, which in turn may lead to a disease outcome different from their respective single species biofilms [1–2].

Pathogenic microbes in mixed-species biofilms secrete a wealth of redox-active small molecule secondary metabolites, including P. aeruginosa phenazines [6, 7] and A. fumigatus epipolythiodioxopiperazines (ETPs, with gliotoxin being the best characterized member) [8–10]. In fact, gliotoxin production is associated with biofilm formation in A. fumigatus [11] and both phenazines and gliotoxin have been quantified from patients [12, 13]. Traditionally, much attention has been placed on phenazines and ETPs as microbial toxins that inhibit growth of competing organisms including several fungal species [8, 14–16]. The toxicity is believed to arise in part from their redox activity and concomitant generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [8, 9, 15, 17]. Despite being toxic at high levels, growing evidence suggests that ROS, at moderate levels, play regulatory roles including signaling the morphogenetic transition between vegetative growth and conidiation (asexual sporulation) in filamentous fungi like Neurospora and Aspergillus [18–20]. This has important implications because, for filamentous fungi such as pathogenic Aspergillus, biofilm formation begins with the production of conidia and the attachment of conidia to a surface [21, 22].

Though little is known in filamentous fungi, oxidative stress hormesis mediated by moderate levels of “toxic” metabolites has been demonstrated in humans [23], and more recently in yeast with respect to signaling biofilm development [24]. In the context of bacterial-yeast biofilms, moderate levels of the phenazine “toxins”, P. aeruginosa-secreted 5-methyl-phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (5-Me-PCA) and its synthetic surrogate phenazine methosulfate (PMS), have been shown to signal Candida albicans biofilm morphological development through altering fungal respiratory activity [25]. This study suggests that interspecies signaling is present between bacteria and yeast, but as for whether it is induced by metabolite oxidative stress is unknown. Considering the compilation of these observations together, we asked if redox-active “toxic” microbial metabolites such as phenazines and gliotoxin could signal filamentous fungal conidiation via oxidative stress regulation.

To address this, here we show that P. aeruginosa phenazine-derived metabolites differentially modulated A. fumigatus development in co-culture biofilms. A. fumigatus development shifted from growth inhibition to weak vegetative growth to vigorous conidiation along a decreasing phenazine gradient in association with differential ROS formation from phenazine redox cycling in an environment-dependent manner. This conidiation induction response was conserved in the genetic model A. nidulans and required NapA, a homolog of AP-1-like bZIP transcription factor, essential for the response to oxidative stress in humans and yeast, as well as filamentous fungi [26–28]. Gliotoxin, another redox-active secondary metabolite, also signals A. nidulans conidiation via NapA regulation. In summary, this work uncovers an unparalleled view that “toxic” microbial metabolites can act as conserved interspecies signals affecting filamentous fungal development via an operative oxidative stress response pathway in fungi.

Results

Phenazine Production Modulates P. aeruginosa–A. fumigatus Phenotypes in Co-culture Biofilms

In P. aeruginosa, phenazine synthesis initiates with phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (PCA) from chorismic acid by the gene products within two redundant operons phzA1-G1 and phzA2-G2; PCA can then be methylated by PhzM to make 5-Me-PCA, the precursor for pyocyanin (PYO); PCA can also be enzymatically modified to make 1-hydroxyphenazine (1-OH-PHZ) and phenazine-1-carboxamide (PCN) [7] (Figure S1A). To investigate the effects of differentially secreted phenazines on P. aeruginosa–A. fumigatus interactions in a biofilm setting, we conducted co-culture experiments of wild-type A. fumigatus (AF293) with the following four P. aeruginosa PA14 strains: the wild-type, the Δphz mutant (missing operons phzA1-G1 and phzA2-G2) producing no phenazines, the phzM::TnM mutant (disrupted in gene phzM) producing neither 5-Me-PCA nor PYO, and the DKN370 mutant (containing two copies of phzM) capable of overproducing 5-Me-PCA and/or PYO (Table S1). Both fungal and bacterial growth patterns varied dependent on which PA14 strain was used. The differential effects observed included changes in bacterial colony size, fungal inhibition zones and fungal conidiation. In contrast to Δphz, all three phenazine-producing PA14 strains inhibited fungal growth, as demonstrated by a visible annulus surrounding the bacterial colony peaked at day 2~3 (Figure 1A), allowing these PA14 strains to reach larger colony sizes than Δphz (Figure 1B). This differed from axenic cultures in which Δphz reached a slightly larger colony size than the other three PA14 strains used (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Phenazine production modulates P. aeruginosa–A. fumigatus interaction phenotype in co-culture biofilms. (A) Scanning images of co-culture plates following development of PA14 (phenazine-producing DKN370, wild-type and phzM::TnM, and phenazine-null Δphz) colonies and AF293 (wild-type A. fumigatus) lawns over 7 days. Scale bar, 2.5 cm. (B) Surface coverage of PA14 colonies in co-cultures (left) and axenic control cultures (right). (C) Microscopic images at day 6 showing: spatially dependent AF293 conidiation within an operationally defined co-culture interaction zone from the edge of PA14 colonies (left to right); homogeneous AF293 conidiation in its axenic control cultures. Scale bar, 0.5 mm. (D) Quantification of AF293 conidiation in the co-culture interaction zone and in axenic control cultures. (E) Quantification of phenazines secreted by co-cultures with the phenazine producing PA14 strains over 7 days. Results are representative of four biological replicate experiments. Error bars indicate SD of four replicates. See also Figure S1, S2, and S3; Table S1.

Most striking was impact of the different PA14 strains on A. fumigatus conidiation, which was demonstrated by green conidial pigmentation as well as the number of conidia as quantified in an operationally defined interaction zone (Figure 1A, 1C and 1D). In particular, DKN370 induced a five-fold increase in A. fumigatus conidiation as compared with the A. fumigatus axenic cultures (Figure 1D); and interestingly, DKN370 was the only strain that secreted appreciable amounts of 5-Me-PCA and PYO, regardless of whether cultured alone or with fungus (Figure 1E and S1B, see also Figure S2 and the Supplemental Results for 5-Me-PCA characterization). By contrast, the PA14 wild-type and phzM::TnM both significantly repressed A. fumigatus conidiation (Figure 1D); these co-cultures secreted higher amounts of PCN, 1-OH-PHZ, 1-methoxyphenazine (1-Me-PHZ), and phenazine-1-sulfonate (SUL-PHZ) than DKN370 co-cultures (Figure 1E, see also Figure S1B, S1C, and S2 and the Supplemental Results for characterization of 1-Me-PHZ and SUL-PHZ). A. fumigatus conidiation was not affected in co-cultures with Δphz in the absence of phenazines (Figure 1D).

5-Me-PCA and PMS at High Concentrations Inhibit Growth but at Moderate Concentrations Enhance Conidiation in A. fumigatus

Considering DKN370 was the only PA14 strain to induce A. fumigatus conidiation, as well as secreting appreciable amounts of 5-Me-PCA and PYO, we hypothesized that 5-Me-PCA and/or PYO was responsible for the enhanced conidiation. A hole-diffusion assay (using partially purified organic and aqueous fractions of mixed cultures due to the unstable nature of 5-Me-PCA [29]) indicated that 5-Me-PCA induced conidiation in A. fumigatus, reflected by green conidial pigmentation (Figure 2A) and number of conidia (Figure 2B) in the region immediately surrounding the exogenous application on a gradient scale (Figure 2C). The highest numbers of conidia were seen with day 4 organic extracts and day 5 aqueous extracts, concomitant with the highest concentrations of 5-Me-PCA in the respective extracts. Conversely, no such correlation was observed with PYO (Figure 2C). This enhanced conidiation was not observed in A. fumigatus cultures treated with extracts from co-cultures with wild-type PA14 (containing neither 5-Me-PCA nor PYO) or from self-extracts, which contains no phenazines (Figure 2A and 2B). Together, this data suggested that 5-Me-PCA at the moderate concentrations tested here, is most likely the primary phenazine responsible for enhanced conidiation.

Figure 2.

5-Me-PCA and PMS at high concentrations inhibit growth but at moderate concentrations enhance conidiation in A. fumigatus (AF293 wild-type). (A–C) 5-Me-PCA at moderate concentrations is the primary phenazine responsible for the enhanced conidiation. Green conidial pigmentation (A) and number of conidia (B) in the region immediately surrounding exogenous application measured for the hole-diffusion assay, after treating AF293 lawns for 6 days with organic and aqueous fractions of extracts prepared from co-cultures of AF293 with DKN370 and wild-type PA14, and AF293 axenic cultures collected periodically throughout incubation. Letters indicate p < 0.001 using a one-way ANOVA test for statistical significance with SigmaPlot, version 12.0. (C) Concentrations of 5-Me-PCA and PYO in the treatment extracts prepared from co-cultures of AF293 with DKN370. (D) 5-Me-PCA and PMS can elicit the switch between inhibiting growth and enhancing conidiation along concentration gradients. Green conidial pigmentation and growth inhibition are imaged and graphically represented for the hole-diffusion assay, after treating AF293 lawns for 4 days with 5-Me-PCA and PMS at different concentrations (from left to right): 315 μM, 36 μM, and 2 μM for 5-Me-PCA; 800 μM, 200 μM, and 40 μM for PMS. See also Table S2 for all phenazine species concentrations in crude extracts. Images (A and D) are representative of biological triplicate plates; scale bars, 2.5 cm. Error bars indicate SD of biological triplicates.

We suspected that 5-Me-PCA might have contributed to the shift from inhibiting growth to enhancing conidiation in A. fumigatus (Figure 1A and 1C). To test this, we treated wild-type A. fumigatus with semi-purified DKN370 culture extracts containing different concentrations of 5-Me-PCA while keeping the concentrations of other phenazines relatively unchanged (Table S2). 315 μM 5-Me-PCA caused a strong shift from inhibiting growth to enhancing conidiation in A. fumigatus along the decreasing gradient of its application; 36 μM 5-Me-PCA enhanced conidiation immediately next to its application; 2 μM 5-Me-PCA showed no effect on fungal development (Figure 2D). Furthermore, aqueous solutions of pure synthetic PMS, previously reported as a 5-Me-PCA surrogate [15], caused concentration dependent development effects on A. fumigatus similar to those of 5-Me-PCA extracts (Figure 2D). However, PYO up to its aqueous solubility threshold (~ 800 μM) showed little effect. Together, these results suggested that 5-Me-PCA and PMS at their respective high concentrations inhibit growth, but at moderate concentrations induce conidiation in A. fumigatus.

5-Me-PCA, PMS and PYO Modulate A. fumigatus Growth and Conidiation via Formation of Radical Intermediates

5-Me-PCA, PMS and PYO are all zwitterionic N-alkylated phenazines, which can be oxidized and reduced in distinct one-electron steps, thereby passing through a semiquinoid intermediate known as N-alkylphenazyl free radical [30]. When oxygen is involved in the one-electron transfer steps, formation of ROS is triggered [15, 17], a known signal for sporulation in fungi [18–20]. This led us to hypothesize that the differential effects on A. fumigatus conidiation mediated by 5-Me-PCA, PMS and PYO may arise from differences in the levels of phenazine radicals (and concomitantly ROS species) formed via one-electron transfer during phenazine redox cycling between cellular reductants and oxygen.

To test this hypothesis, we investigated factors known to impact formation and stability of phenazine radicals. Firstly, the redox potentials (E1/2) of different phenazines were compared as a higher E1/2 suggests that the phenazine radical formed would be more stable under aerobic (i.e., oxidizing) and physiological pH conditions [30, 31]. Using cyclic voltammetry, we estimated E1/2 values for 5-Me-PCA in the pH range (4.2–8.0) relevant for our co-culture conditions (detailed in Figure S3 and S4A, Table S3 and the Supplemental Results). We found that the abilities of N-alkylated phenazines to induce A. fumigatus conidiation decrease in the same order as their E1/2 values (vs. NHE (normal hydrogen electrode), illustrated with E1/2 at pH 7.0): 5-Me-PCA (+129 mV) > PMS (+80 mV) > phenazine ethosulfate (PES, +55 mV) > PYO (−40 mV) [32, 33] (Figure 3A, Table S3).

Figure 3.

5-Me-PCA, PMS, and PYO modulate A. fumigatus (AF293 wild-type) conidiation via formation of radical intermediates. (A) Phenazines modulate AF293 conidiation and growth via E1/2-dependent redox activity. See also Figure S5A. (B) Adding a radical scavenging solvent (10 % ethanol, methanol or DMSO), or (C) increasing the assay pH to 8.0, or adding ascorbic acid (AA, 10 mM) but not H2O2 (10 mM) significantly represses the enhanced conidiation caused by 5-Me-PCA (36 μM) or PMS (200 μM), as reflected by green conidial pigmentation surrounding the treatment hole imaged in biological triplicate plates at day 4. Scale bars, 2.5 cm. See also Table S2 for all phenazine species concentrations in crude extracts. (D) Decreasing the assay pH to 2.6 helps PYO to enhance AF293 conidiation, as quantified at day 6 for the region immediately surrounding the treatment hole. Error bars indicate SD of biological triplicates. (E) Representative cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of 200 μM PYO in aqueous electrolytes buffered at pH 2.6 versus 4.2. Scan rate, 20 mV/s. See also Table S3.

We then investigated the effects of environmental factors on conidiation induction caused by moderate concentrations of 5-Me-PCA and PMS. First, the addition of a radical scavenging solvent (10 % ethanol, methanol or DMSO [34]) significantly repressed phenazine-induced conidiation (Figure 3B). Second, for a given N-alkylated phenazine, stepwise one-electron transfer with a “stable” radical intermediate produced is favored at acidic pH; and concurrent two-electron transfer bypassing the radical intermediate becomes favored as the pH increases [30]. Consistent with this radical stability trend, increasing the assay pH from slightly acidic (pH 4.2–6.5, Figure S3) to 8.0 (buffered with MOPS) notably repressed phenazine-induced conidiation (Figure 3C, I–III). Third, radical intermediate can be destabilized by adding an oxidant or a reductant, for high E1/2 chemicals, such as 5-Me-PCA and PMS, their radical intermediates are expected to be thermodynamically more stable in the presence of an oxidant, but less stable in the presence of a reductant [30, 31]. In accordance, addition of the mild reductant ascorbic acid [15, 30] significantly repressed, whereas the oxidant H2O2 only slightly repressed phenazine-induced conidiation (Figure 3C, I, IV, and V).

Finally, considering PYO has a much lower E1/2 than 5-Me-PCA and PMS, we reasoned that it requires a lower pH to favor radical formation [30, 31]. As expected, lowering the assay pH to 2.6 helped the otherwise ineffective PYO to induce conidiation, especially at higher PYO concentrations (Figure 3D). Formation of a “stable” PYO radical at pH 2.6 was supported by cyclic voltammetry (CV) showing two pairs of conjugated anodic (oxidation) and cathodic (reduction) peaks, characteristic of a reversible electrode reaction involving two one-electron steps [35] (Figure 3E). Whereas at pH 4.2, the CV peaks merged into a single pair of conjugated peaks, indicating that a reversible two-electron coupled process, which bypasses formation of the PYO radical, became more important [35] (Figure 3E). Not surprisingly, factors destabilizing the PYO radical, such as increasing the assay pH, addition of ascorbic acid or H2O2, did not induce conidiation (Figure 3C). Collectively, these results indicated that amounts and formation of radical species is responsible for the differential modulation of A. fumigatus development induced by N-alkylated phenazines.

Phenazines and Gliotoxin Redox-Signaling in Aspergillus Development Requires NapA, the Conserved Oxidative Stress Responsive bZIP Protein

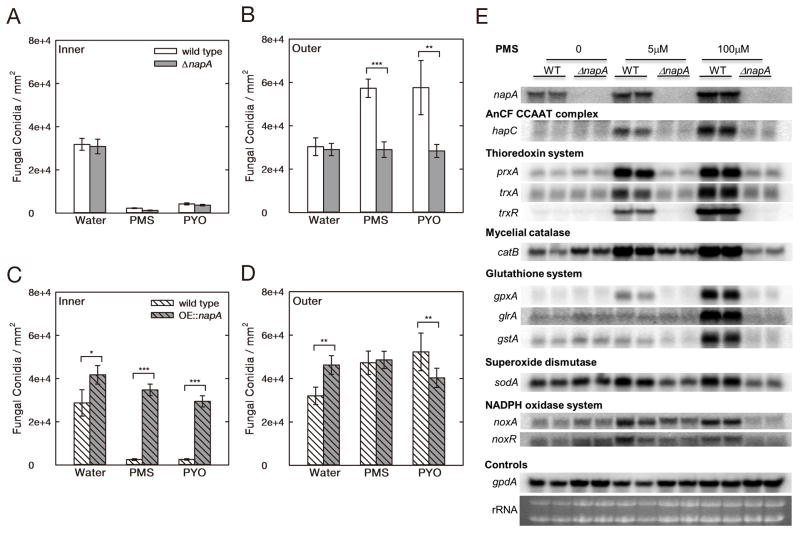

Having shown that phenazines can inhibit or induce A. fumigatus conidiation, dependent on the levels of radical intermediates formed, we predicted that the conidiation response is a conserved phenomenon, and requires an operative stress response pathway in fungi. NapA, a homolog of the AP-1-like bZIP type transcription factor associated with oxidative responses from humans to yeast, has been characterized in A. nidulans as essential for response to oxidative stressors and involved in asexual sporulation [26–28]. Therefore, hole-diffusion assay experiments were conducted by treating preformed lawns of A. nidulans wild-type, napA deletion (ΔnapA) and overexpression (OE::napA) strains with PMS (the 5-Me-PCA surrogate) and PYO. Without addition of phenazine, all three strains grew homogeneously on agar, and conidial production in OE::napA was higher than in wild-type and ΔnapA (Figure 4A–D). Similarly to its impact on A. fumigatus, the PMS solution caused a morphological shift from inhibiting to inducing conidiation in wild-type A. nidulans along a decreasing phenazine gradient (Figure 4A and 4B), though the shift occurred at 40 μM PMS, a concentration lower than for wild-type A. fumigatus (Figure 2D). PYO had a similar impact on conidiation (at 100 μM) in wild-type A. nidulans. In contrast, PMS and PYO did not induce conidiation in ΔnapA and OE::napA, the oxidative stress sensitive and resistant mutants, respectively (Figure 4A–D, and [27]).

Figure 4.

PMS and PYO can induce A. nidulans conidiation through NapA oxidative stress regulation. To quantify the conidiation in A. nidulans strains we operationally defined “Inner” region immediately next to and “Outer” region away from exogenous application in the hole-diffusion assay. (A and B) wild type and napA deletion (ΔnapA) strains, (C and D) wild type and overexpression (OE::napA) strain supplemented with 200 μg/l pyridoxine (auxotrophic marker) were quantified after 3.5 days of treatment with 40 μM PMS or 100 μM PYO. Error bars indicate SD of biological triplicates. Asterisk refers to statistical significance that measured with a student t test of significance using Excel 2007. *, 0.01 < p < 0.05; **, 0.001 < p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. (E) Gene expression analysis of A. nidulans strains, wild type (WT, RDIT9.32) and ΔnapA (RWY10.3) grown in 20 mL liquid GMM at 37 °C with shaking at 225 rpm for 18 h followed by further incubation for 30 min after adding PMS in the cultures at the concentrations of 5μM and 100μM. Ethidium bromide-stained rRNA and gpdA expression are indicated for loading.

This alteration in conidial development in napA mutants suggests that phenazine induction of development occurs through a NapA-dependent oxidative stress pathway. To more concretely examine this hypothesis, we next assessed the impact of PMS treatment on gene expression of representatives from the entire oxidative stress metabolome in both the wild-type and ΔnapA A. nidulans strains taking care to assess known NapA targets. In wild-type, PMS treatment induced expression of not only napA but also hapC (a critical member of the CCAAT-binding factor AnCF which coordinates the oxidative stress response in eukaryotes, [36], catB (mycelial catalase [37]), trxA, trxR and prxA (components of the thioredoxin system, [38]), glrA, gstA and gpxA (the glutathione system, [39, 40]), noxA and noxR (members of the NADPH oxidase complex [41], and sodA (superoxide dismutase, [42]) (Figure 4E). PMS induction of all of these genes was NapA dependent. Notably, both levels of PMS were effective in inducing high expression of most systems with the exception of genes involved in glutathione metabolism. High expression of all three components required 100 μM PMS, possibly reflecting a greater need for accurate glutathione levels with higher ROS levels. Both GstA and GlrA have been characterized as responsive to oxidative stress in A. nidulans [40] whereas GpxA, a putative glutathione peroxidase, is yet to be thoroughly characterized [36].

We further predicted that the requirement of NapA in A. nidulans conidiation induction is generalizable to other redox metabolites, such as gliotoxin, a well-studied A. fumigatus mycotoxin [1, 9]. When added alone, gliotoxin inhibited conidiation in ΔnapA, slightly enhanced in wild-type and did not affect conidiation in OE::napA at day 4; in contrast, under mildly reducing conditions achieved by adding ascorbic acid, gliotoxin had little effect on ΔnapA conidiation, but enhanced conidiation approximately 2.5-fold in wild-type and 5-fold in OE::napA (Figure 5 and S6). Together, these results not only confirmed that “toxic” microbial redox metabolites can operate as conserved signals affecting fungal development, but strongly suggest that the conidiation induction response to these metabolites occurs through fine-tuned oxidative stress regulation in the fungus, in order to cope with diverse oxidative stressors associated with variable environments.

Figure 5.

Gliotoxin can induce A. nidulans conidiation under mildly reducing conditions through NapA oxidative stress regulation. Effects of gliotoxin alone or together with 100 mM ascorbic acid (AA) on fungal conidiation quantified for each A. nidulans wild-type and napA deletion (ΔnapA) (Left) or wild type and overexpression (OE::napA) strain supplemented with 200 μg/l pyridoxine (Right) after 4 days of treatment. Error bars indicate SD of biological triplicates. See also Figure S6. Asterisk refers to statistical significance that measured with a student T-test of significance using Excel 2007. *, 0.01 < p < 0.05; **, 0.001 < p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

Discussion

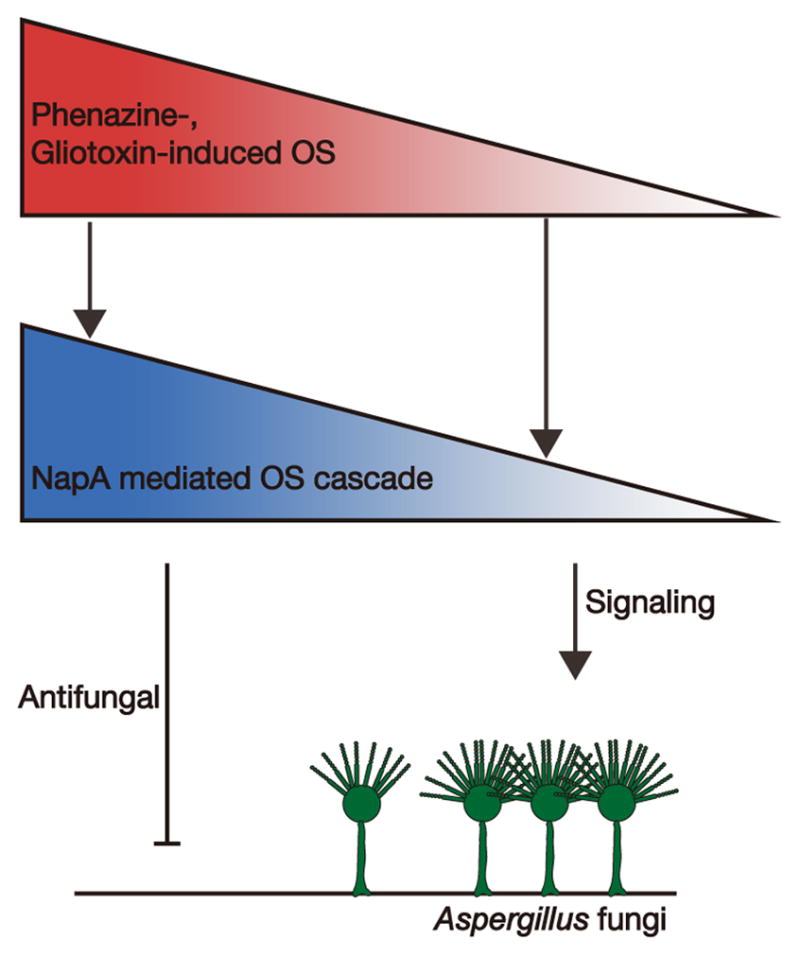

The important role that oxidative stress may play in signaling microbial community development is only beginning to be appreciated [24]. Motivated by recent work implicating that low doses of “toxic” metabolites can signal biofilm formation in yeast via the oxidative stress response [24], we hypothesized that this phenomenon is also important in mixed-species biofilm formation involving filamentous fungi. As presented in a model of oxidative stress hormesis (Figure 6), our work provides the first demonstration that bacterial and fungal metabolites, traditionally recognized for their redox toxicity, can instead act as sporulation signals, affecting filamentous fungal development in mixed-species communities.

Figure 6.

Model of oxidative stress (OS) hormesis mediated by “toxic” microbial redox metabolites in filamentous fungal development. Phenazines and gliotoxin, through inducing differential levels of oxidative stress controlled by metabolite redox properties and their environment-dependent activities, play dual roles as a toxin (high levels) and as a conidiation signal in Aspergillus development (moderate levels), which is fine-tuned by the NapA oxidative stress response pathway.

We found that bacterial phenazine production differentially modulates P. aeruginosa–A. fumigatus co-culture biofilm formation (Figure 1). A. fumigatus development was shifted from weak vegetative growth to vigorous conidiation along phenazine gradients (Figure 1A and 2D), correlating with levels of phenazine radicals (and concomitantly ROS) formed during phenazine redox cycling (Figure 3). Our finding thus complements studies implicating the dual role of ROS as a toxin (high levels) and as a sporulation signal in fungal development (moderate levels) [18–20]. Furthermore, this conidiation induction response is conserved in A. nidulans and requires NapA (Figure 4 and 5). Unlike wild-type, phenazine-induced conidiation was not observed with ΔnapA and OE::napA, two strains with contrasting oxidative stress susceptibilities [27]. A significant observation from our work was the unexpected finding that NapA was critical in transmitting the phenazine redox signal to a multitude of oxidative response pathways in the fungus, including the CCAAT-binding complex AnCF, the thioredoxin, glutathione and NADPH oxidase systems as well as ROS active enzymes CatB and SodA (Figure 4E). We also note that while gliotoxin-induced conidiation also requires NapA, conidiation was also observed with both wild-type and OE::napA under mildly reducing conditions (Figure 5 and S6). Thus, our data not only support a conserved function for diverse microbial redox metabolites in signaling filamentous fungal development via NapA oxidative stress regulation, but also strongly suggest that the fungus has evolved fine-tuned oxidative stress regulation for its proper response to different metabolite signals.

We observed that the regulatory differences on Aspergillus development appear to be highly coordinated with metabolite redox activities under varying environments. Environmental changes are common in mixed-species biofilms, including those where Aspergillus spp. and P. aeruginosa can coexist. For example, abnormal acidification has been documented for CF airways [43] and acute wounds during inflammation [44]. For N-alkylated phenazines, radical formation is predicted to be favored as the pH decreases [30, 31]. As expected, increasing pH to weakly alkaline repressed conidiation induced by moderate levels of 5-Me-PCA (and PMS) (Figure 3B, I–III), while decreasing pH allowed the ineffective PYO to induce conidiation in A. fumigatus (Figure 3D). pH adaptation has been shown to be critical for virulence in A. nidulans [45] and speculated as a pathogenic trait of A. fumigatus [46], though the potential contribution by pH-dependent conidiation signaling remains to be determined. Biofilms are also known to experience temporal and spatial oxygen gradients [47]. As infections progress, cell densities increase and oxygen tensions decline within CF airways [48]. We showed that, as the ambient redox conditions become more reduced, the conidiation signaling activity caused by the high E1/2 5-Me-PCA (and PMS) can be repressed (Figure 3B, I and IV), whereas the inhibitory activity caused by the low E1/2 PCN- and 1-Me-PHZ can be weakened, or even shifted, to signaling fungal development (Figure S5A). Curiously, in co-culture biofilms, 5-Me-PCA, if secreted, reached its highest concentration at an earlier time, but PCN and 1-Me-PHZ were secreted in higher amounts at later time points (Figure 1E) as biofilms presumably became more oxygen-limited. On a similar note, gliotoxin-induced A. nidulans conidiation was favored under mildly reducing conditions (Figure 5 and S6), and interestingly a recent study reported increased gliotoxin secretion in A. fumigatus biofilms containing oxygen-limited microenvironments as compared with shaken planktonic cultures [11]. It would thus seem that, in mixed-species biofilms, redox metabolite-modulated fungal development and their production coordinately respond to the varying redox conditions.

In addition, we observed that Aspergillus converts pseudomonal PCA into phenazine products (1-OH-PHZ, SUL-PHZ and 1-Me-PHZ) with different effects on fungal development. While the redox activity of 1-Me-PHZ can modulate Aspergillus development, PCA and 1-OH-PHZ have been reported to differentially affect Aspergillus siderophore production [16], suggesting that metabolite conversions by neighboring microbes can affect mixed-species biofilms in multiple ways. Pertinent to these findings, fungal secondary metabolism (including siderophore production) and oxidative stress response have been recently implied to be co-regulated in a highly coordinated manner by NapA and another bZIP protein, AtfB [27, 49]. Going forward, it will be of interest to explore whether phenazines (and other redox metabolites) can also direct Aspergillus secondary metabolism via the active oxidative stress response.

The complexity of the microbial community in environments ranging from the lungs of CF patients to the rhizosphere, and the interactions among its members are only beginning to be appreciated. With the common perception that such communities are highly competitive, much attention has been placed on secreted microbial metabolites as toxins to mediate antagonistic interspecies interactions [14, 15, 50]. In the context of CF infections, Mowat et al. recently showed that P. aeruginosa inhibited A. fumigatus biofilm formation through the secretion of diffusible small molecule metabolites [50]. Though not identified in their specific experimental conditions, signal-mediated interactions between P. aeruginosa and A. fumigatus are possible, considering the heterogeneous nature of the CF microenvironments [43, 48, 51] and that interspecies signaling has been discovered between CF isolates of P. aeruginosa and the yeast C. albicans [25, 52]. Here we show that phenazines and gliotoxin, through their environment-dependent redox activities, can shift from acting as antifungal molecules to sporulation signals affecting Aspergillus development, via a NapA mediated oxidative stress response pathway. In fact, P. aeruginosa phenazines are present in CF sputum at concentrations between 1 and 100 μM [12, 51], moderate enough for some phenazines to signal Aspergillus development (Figure 2 and 4). Thus, phenazine signaling might contribute to the observations that lung functions of CF patients co-infected by P. aeruginosa and A. fumigatus worsen more than those infected by each organism alone [1, 2]. We contend that signal-mediated interactions can also occur between different Aspergillus species, supported by the illustration that the fungal ETP metabolite gliotoxin can signal A. nidulans development (Figure 5) and is produced by diverse A. fumigatus isolates but not by A. nidulans [8, 9]. Furthermore, soil microbes (including Aspergillus and Pseudomonas) co-colonizing plant roots in the rhizosphere are known to experience diverse oxidative stressors under varying environments [53, 54]. Accordingly, microbial redox signals may be of great relevance in the rhizosphere. As suggested here, a fuller understanding of interspecies redox signaling may help predict microbial community dynamics, and thus shed light on novel strategies for treating polymicrobial diseases as well as mitigating the virulent inhabitants of the rhizosphere.

Experimental Procedures

P. aeruginosa–A. fumigatus Co-culture Experiments

AF293 lawns were prepared and incubated at 25 °C for 12 h, followed by spot-inoculating 10 μl aliquots of early stationary phase PA14 cultures (DKN370, wild-type, phzM::TnM, or Δphz) onto the preformed fungal lawns. The co-cultures and axenic cultures of PA14 strains and AF293 were incubated at 25 °C for an additional 7 day. Plates of co-cultures and axenic control cultures were imaged daily using an EPSON Perfection V300 Photo Scanner at 600 dpi resolution.

Extraction Protocols for the Phenazine-Treatment and Electrochemical Experiments involving 5-Me-PCA

Extraction cores (38.1 mm in diameter) were cut from 5 plates of DKN370-AF293 co-cultures, PA14-AF293 co-cultures, and AF293 axenic cultures and transferred to a blender containing 50 ml of water and homogenized. The slurry was transferred to a glass flask. 50 ml of chloroform was added. The mixture was shaken vigorously at 225 rpm for an hour at 25 °C, and filtered through Miracloth. The filtered chloroform and aqueous phases were then transferred to a separatory funnel, and collected individually. The chloroform fraction was evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph), and re-dissolved in 50 ml of water. The organic and aqueous fractions were each filtered through a 0.2 μm-pore-size hydrophilic filter, analyzed with HPLC, and stored in glass vials at −20 °C.

DKN370 axenic cultures (20 plates) were incubated at 25 °C for 7 days, next homogenized and extracted twice with 200 ml of chloroform. The combined chloroform fractions were filtered through Miracloth and 0.5 μm-pore-size hydrophobic filters. Next, filtrates were evaporated to dryness, re-dissolved in different volumes of water to obtain the desired concentrations of 5-Me-PCA.

DKN370, PA14 wild type and Δphz cultures (10 plates each) were incubated in parallel at 25 °C for 4 days, next homogenized and extracted twice with 100 ml of chloroform. The combined chloroform fractions were filtered through Miracloth as well as 0.5 μm-pore-size hydrophobic filters to remove cell and agar debris, and then evaporated to dryness.

Metabolite-treatment Experiments

A hole-diffusion assay mimicking co-culture biofilm conditions was designed to assess the roles of a metabolite of interest on Aspergillus growth and conidiation. After incubating the lawn cultures of AF293 for 36 h and A. nidulans strains (RDIT9.32 wild-type, RWY10.3 ΔnapA, RWY17.3 OE:: napA) for 12 h at 25 °C, a hole of 2.5 cm in diameter was cut into the center of a plate, and filled with 2.0 ml of a test solution. Each plate was incubated at 25 °C for up to an additional 6 days with AF293 or up to an additional 4 days with A. nidulans strains. The test solution in the hole was gently removed and replaced with fresh solution using sterile pipette tips every 24 h throughout the incubation period. Biological triplicate experiments were performed and analyzed for each treatment condition.

A more detailed description of methods is provided in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Related to Figure 1.

(A) Phenazine biosynthesis pathway of P. aeruginosa (solid arrows) and bioconversion pathway of P. aeruginosa phenazines by A. fumigatus (AF293 wild-type; dashed arrows). (B) Quantitative analyses of differentially secreted phenazines extracted from axenic cultures of three phenazine-producing PA14 strains (DKN370, wild-type, and phzM::TnM) after 5 days of incubation on YPD plates. Error bars indicate SD of four biological replicates. 5-Me-PCA is quantified as the average of biological duplicates. (C) AF293 converts the P. aeruginosa PCA into SUL-PHZ and 1-Me-PHZ through the intermediate 1-OH-PHZ. Without AF293, PCA maintains its original concentration throughout the 7-day incubation period on YPD plates. Error bars indicate SD of biological triplicates.

Figure S2. Structural characterization of phenazines. Related to Figure 1E.

(A) HPLC chromatograms (367 nm) of different phenazines detected from chloroform and aqueous fractions of extracts of DKN370–AF293 (wild-type A. fumigatus) co-cultures after 4 days of incubation on YPD plates. (B) UV chromatographs of different phenazines, with the wavelengths of absorption maxima for each phenazine labeled in the plots. (C) Accurate masses determined for 5-Me-PCA and SUL-PHZ, as well as the SUL-PHZ fragment (predicted as 1-OH-PHZ) after losing the -SO3 group, using a LC/ESI TOF mass spectrometer (table; figures, left and middle); mass spectrum of 1-Me-PHZ (figure, right).

Figure S3. pH changes in agar media during growth of A. fumigatus (AF293 wild-type) axenic cultures and co-cultures with DKN370 and wild-type PA14 on YPD plates. Related to Figure 1 and the Results section.

Figure S4. Electrochemical properties of 5-Me-PCA (A), 1-Me-PHZ (B), and SUL-PHZ (C). Related to Figure S5A and the Results section.

(A) Representative cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of samples with 5-Me-PCA (prepared from DKN370 culture extracts), without 5-Me-PCA (from PA14 wild-type culture extracts supplemented with PYO), and without phenazines (from PA14 Δphz culture extracts). Organic extracts were collected after incubating PA14 cultures on YPD plates for 4 days. Scan rate: 200 mV/s. See also Table S2 for all phenazine species concentrations in crude extracts. (B and C) Representative cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of 1-Me-PHZ and SUL-PHZ measured at different scan rates at pH 7.0 (left); the peak current vs. square root of voltage scan rate at pH 7.0 (middle); the mid-point potential (E1/2) vs. pH that are derived from CVs measured at different scan rates and pHs respectively (right). The CV test solutions were prepared by dissolving dried extracts, 54 μM 1-Me-PHZ, or 83 μM SUL-PHZ in 0.1 M KCl aqueous electrolyte buffered with 10 mM CH3C(O)ONH4–MOPS (5 mM each) in the pH range 4.2–8.0, or with 0.1 % formic acid (26.5 mM) at pH 2.6.

Figure S5. Hole diffusion assay to test PCA, SUL-PHZ, 1-OH-PHZ, PCN and 1-Me-PHZ effects on A. fumigatus (AF293 wild-type) development. Related to the Results section.

(A) Scanning images of plates were obtained for the hole-diffusion assay, after treating AF293 lawns for 6 days with a phenazine (I), or a phenazine together with the pH buffer MOPS (100 mM, pH 6.5 and 8.0) (II and III), ascorbic acid (AA, 100 mM) (IV), or H2O2 (10 mM) (V). (B) Scanning images of plates were obtained for the hole-diffusion assay after treated for 5 days with a phenazine (200 μM PCA, 200 μM SUL-PHZ, and 120 μM 1-OH-PHZ), or a phenazine together with the pH buffer formic acid (26.5 mM, pH 2.6). Water (i.e., no buffer), MOPS, AA, and H2O2, formic acid added alone served as the respective controls. Scale bar, 2.5 cm. Results are representative of biological triplicate experiments.

Figure S6. Gliotoxin can signal A. nidulans development under mildly reducing conditions through NapA oxidative stress regulation, as reflected by green conidial pigmentation. Related to Figure 5 and the Experimental Procedures section.

Scanning images of the plate region (illustrated in the top panel) for each A. nidulans (wild-type, napA deletion (ΔnapA) or overexpression (OE::napA)) strain were obtained after 4 days of treatment with no addition (i.e., water control), or with the addition of gliotoxin, ascorbic acid (AA) or gliotoxin together with AA. The gliotoxin suspension (200 μM) was applied homogeneously to the overlaying medium containing fungal conidia. The AA solution (100 mM) was applied to the treatment hole to create a redox gradient (distance from its application). Images are representative of biological triplicate experiments.

Table S1. Bacterial and fungal strains used in this study. Related to Figures 1–5.

Table S2. Concentrations of phenazine species in the crude extract samples. Related to Figures 2A, 2D; Figures 3A, 3B; Figures S4A.

Table S3. Redox potentials (E1/2) of phenazines in aqueous solution. Related to Figures 3D and S5A, and the Results section.

Table S4. Primers used in this study. Related to Figure 4E.

Acknowledgments

We thank D.A. Hogan for the PA14 phzM::TnM strain, J.-F. Gaillard for inputs on cyclic voltammetry experiments, and Y. Jiao and Wang lab members for discussions. This work was supported by startup and ISEN funding from Northwestern University (to Y.W.), National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM 067725 (to N.L.K.), and National Science Foundation Grant Emerging Frontiers in Research and Innovation 1136903 (to N.P.K.).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes six figures, three tables, Supplemental Results, and Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Author Contributions

Y.W., H.Z., and N.P.K. designed research; H.Z., J.K., M.L., J.K.Y., J.-W.B. and O.H. performed research; N.L.K. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; H.Z., Y.W., J.K., M.L., and J.K.Y. analyzed data; and Y.W., N.P.K. and H.Z. wrote the paper. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Amin R, Dupuis A, Aaron SD, Ratjen F. The effect of chronic infection with Aspergillus fumigatus on lung function and hospitalization in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2010;137:171–176. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peleg AY, Hogan DA, Mylonakis E. Medically important bacterial-fungal interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:340–349. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Creenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latge JP. Aspergillus fumigatus and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:310–350. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manavathu EK, Vager DL, Vazquez JA. Development and antimicrobial susceptibility studies of in vitro monomicrobial and polymicrobial biofilm models with Aspergillus fumigatus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price-Whelan A, Dietrich LEP, Newman DK. Rethinking “secondary” metabolism: physiological roles for phenazine antibiotics. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nchembio764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mavrodi DV, Bonsall RF, Delaney SM, Soule MJ, Phillips G, Thomashow LS. Functional analysis of genes for biosynthesis of pyocyanin and phenazine-1-carboxamide from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6454–6465. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6454-6465.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carberry S, Molloy E, Hammel S, O’Keeffe G, Jones GW, Kavanagh K, Doyle S. Gliotoxin effects on fungal growth: mechanisms and exploitation. Fungal Genet Biol. 2012;49:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher L, Owens RA, Dolan SK, O’Keeffe G, Schrettl M, Kavanagh K, Jones GW, Doyle S. The Aspergillus fumigatus protein GliK protects against oxidative stress and is essential for gliotoxin biosynthesis. Eukaryot Cell. 2012;11:1226–1238. doi: 10.1128/EC.00113-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi HS, Shim JS, Kim JA, Kang SW, Kwon HJ. Discovery of gliotoxin as a new small molecule targeting thioredoxin redox system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruns S, Seidler M, Albrecht D, Salvenmoser S, Remme N, Hertweck C, Brakhage AA, Kniemeyer O, Muller FMC. Functional genomic profiling of Aspergillus fumigatus biofilm reveals enhanced production of the mycotoxin gliotoxin. Proteomics. 2010;10:3097–3107. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson R, Sykes DA, Watson D, Rutman A, Taylor GW, Cole PJ. Measurement of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazine pigments in sputum and assessment of their contribution to sputum sol toxicity for respiratory epithelium. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2515–2517. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.9.2515-2517.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis RE, Wiederhold NP, Chi J, Han XY, Komanduri KV, Dimitrios P, Prince RA, Kontoyiannis DP. Detection of gliotoxin in experimental and human aspergillosis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:635–637. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.635-637.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr JR, Taylor GW, Rutman A, Hoiby N, Cole PJ, Wilson R. Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyocyanin and 1-hydroxyphenazine inhibit fungal growth. J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:385–387. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.5.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morales DK, Jacobs NJ, Rajamani S, Krishnamurthy M, Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Hogan DA. Antifungal mechanisms by which a novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazine toxin kills Candida albicans in biofilms. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78:1379–1392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moree WJ, Phelan VV, Wu CH, Bandeira N, Cornett DS, Duggan BM, Dorrestein PC. Interkingdom metabolic transformations captured by microbial imaging mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13811–13816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206855109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lau GW, Hassett DJ, Ran H, Kong F. The role of pyocyanin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gyöngyösi N, Nagy D, Makara K, Ella K, Káldi K. Reactive oxygen species can modulate circadian phase and period in Neurospora crassa. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;58:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernández-Oñate Ma, Esquivel-Naranjo EU, Mendoza-Mendoza A, Stewart A, Herrera-Estrella AH. An injury-response mechanism conserved across kingdoms determines entry of the fungus Trichoderma atroviride into development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14918–14923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209396109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang PK, Scharfenstein LL, Luo M, Mahoney N, Molyneux RJ, Yu J, Brown RL, Campbell BC. Loss of msnA, a putative stress regulatory gene, in Aspergillus parasiticus and Aspergillus flavus increased production of conidia, aflatoxins and kojic acid. Toxins (Basel) 2011;3:82–104. doi: 10.3390/toxins3010082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dagenais TRT, Keller NP. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in invasive aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:447–465. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00055-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harding MW, Marques LLR, Howard RJ, Olson ME. Can filamentous fungi form biofilms? Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen G, Riahi Y, Sunda V, Deplano S, Chatgilialoglu C, Ferreri C, Kaiser N, Sasson S. Signaling properties of 4-hydroxyalkenals formed by lipid peroxidation in diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:978–987. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cáp M, Váchová L, Palková Z. Reactive oxygen species in the signaling and adaptation of multicellular microbial communities. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012;2012:976753. doi: 10.1155/2012/976753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morales DK, Grahl N, Okegbe C. Control of Candida albicans Metabolism and Biofilm Formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Phenazines. Mbio. 2013;4:e00526–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00526-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asano Y, Hagiwara D, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. Characterization of the bZip-type transcription factor NapA with reference to oxidative stress response in Aspergillus nidulans. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007;71:1800–1803. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin WB, Reinke AW, Szilágyi M, Emri T, Chiang YM, Keating AE, Pócsi I, Wang CCC, Keller NP. bZIP transcription factors affecting secondary metabolism, sexual development and stress responses in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiol-Sgm. 2013;159:77–88. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.063370-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toone WM, Morgan BA, Jones N. Redox control of AP-1-like factors in yeast and beyond. Oncogene. 2001;20:2336–2346. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansford GS, Herbert RB, Holliman FG. Pigments of Pseudomonas species. IV In vitro and in vivo conversion of 5-methylphenazinium-1-carboxylate into aeruginosin A. J Chem Soc Perkin. 1972;1(1):103–105. doi: 10.1039/p19720000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaugg WS. Spectroscopic characteristics and some chemical properties of N-methylphenazinium methyl sulfate (phenazine methysulfate) and pyocyanine at the semiquinoid oxidative level. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:3964–3970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song Y, Buettner GR. Thermodynamic and kinetic considerations for the reaction of semiquinone radicals to form superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:919–962. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Newman DK. Redox reactions of phenazine antibiotics with ferric (hydr)oxides and molecular oxygen. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:2380–2386. doi: 10.1021/es702290a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fultz ML, Durst RA. Mediator compounds for the electrochemical study of biological redox systems: a compilation. Anal Chim Acta. 1982;140:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chowdhury G, Sarkar U, Pullen S, Wilson WR, Rajapakse A, Fuchs-Knotts T, Gates KS. DNA strand cleavage by the phenazine di-N-oxide natural product myxin under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:197–206. doi: 10.1021/tx2004213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications. 2. New York: John Wiley; 2001. pp. 226–243. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thön M, Al Abdallah Q, Hortschansky P, Scharf DH, Eisendle M, Haas H, Brakhage AA. The CCAAT-binding complex coordinates the oxidative stress response in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1098–1113. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawasaki L, Wysong D, Diamond R, Aguirre J. Two divergent catalase genes are differentially regulated during Aspergillus nidulans development and oxidative stress. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3284–3292. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3284-3292.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thön M, Al-Abdallah Q, Hortschansky P, Brakhage AA. The thioredoxin system of the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans: impact on development and oxidative stress response. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27259–27269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burns C, Geraghty R, Neville C, Murphy A, Kavanagh K, Doyle S. Identification, cloning, and functional expression of three glutathione transferase genes from Aspergillus fumigatus. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato I, Shimizu M, Hoshino T, Takaya N. The glutathione system of Aspergillus nidulans involves a fungus-specific glutathione S-transferase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8042–8053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807771200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Semighini CP, Harris SD. Regulation of apical dominance in Aspergillus nidulans hyphae by reactive oxygen species. Genetics. 2008;179:1919–1932. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.089318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oberegger H, Zadra I, Schoeser M, Haas H. Iron starvation leads to increased expression of Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase in Aspergillus. FEBS Lett. 2000;485:113–116. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poschet J, Perkett E, Deretic V. Hyperacidification in cystic fibrosis: links with lung disease and new prospects for treatment. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:512–519. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneider LA, Korber A, Grabbe S, Dissemond J. Influence of pH on wound-healing: a new perspective for wound-therapy? Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;298:413–420. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bignell E, Negrete-Urtasun S, Calcagno AM, Haynes K, Arst HN, Rogers T. The Aspergillus pH-responsive transcription factor PacC regulates virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1072–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis DA. How human pathogenic fungi sense and adapt to pH: the link to virulence. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stewart PS, Franklin MJ. Physiological heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:199–210. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Worlitzsch D, Tarran R, Ulrich M, Schwab U, Cekici A, Meyer KC, Birrer P, Bellon G, Berger J, Weiss T, et al. Effects of reduced mucus oxygen concentration in airway Pseudomonas infections of cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:317–325. doi: 10.1172/JCI13870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hong SY, Roze LV, Linz JE. Oxidative stress-related transcription factors in the regulation of secondary metabolism. Toxins. 2013;5:683–702. doi: 10.3390/toxins5040683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mowat E, Rajendran R, Williams C, McCulloch E, Jones B, Lang S, Ramage G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their small diffusible extracellular molecules inhibit Aspergillus fumigatus biofilm formation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;313:96–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hunter RC, Klepac-Ceraj V, Lorenzi MM, Grotzinger H, Martin TR, Newman DK. Phenazine content in the cystic fibrosis respiratory tract negatively correlates with lung function and microbial complexity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47:738–745. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0088OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McAlester G, O’Gara F, Morrissey JP. Signal-mediated interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:563–569. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47705-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stockwell VO, Hockett K, Loper JE. Role of RpoS in stress tolerance and environmental fitness of the phyllosphere bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens Strain 122. Phytopathology. 2009;99:689–695. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-99-6-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palumbo JD, O’Keeffe TL, Abbas HK. Isolation of maize soil and rhizosphere bacteria with antagonistic activity against Aspergillus flavus and Fusarium verticillioides. J Food Prot. 2007;70:1615–1621. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.7.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Related to Figure 1.

(A) Phenazine biosynthesis pathway of P. aeruginosa (solid arrows) and bioconversion pathway of P. aeruginosa phenazines by A. fumigatus (AF293 wild-type; dashed arrows). (B) Quantitative analyses of differentially secreted phenazines extracted from axenic cultures of three phenazine-producing PA14 strains (DKN370, wild-type, and phzM::TnM) after 5 days of incubation on YPD plates. Error bars indicate SD of four biological replicates. 5-Me-PCA is quantified as the average of biological duplicates. (C) AF293 converts the P. aeruginosa PCA into SUL-PHZ and 1-Me-PHZ through the intermediate 1-OH-PHZ. Without AF293, PCA maintains its original concentration throughout the 7-day incubation period on YPD plates. Error bars indicate SD of biological triplicates.

Figure S2. Structural characterization of phenazines. Related to Figure 1E.

(A) HPLC chromatograms (367 nm) of different phenazines detected from chloroform and aqueous fractions of extracts of DKN370–AF293 (wild-type A. fumigatus) co-cultures after 4 days of incubation on YPD plates. (B) UV chromatographs of different phenazines, with the wavelengths of absorption maxima for each phenazine labeled in the plots. (C) Accurate masses determined for 5-Me-PCA and SUL-PHZ, as well as the SUL-PHZ fragment (predicted as 1-OH-PHZ) after losing the -SO3 group, using a LC/ESI TOF mass spectrometer (table; figures, left and middle); mass spectrum of 1-Me-PHZ (figure, right).

Figure S3. pH changes in agar media during growth of A. fumigatus (AF293 wild-type) axenic cultures and co-cultures with DKN370 and wild-type PA14 on YPD plates. Related to Figure 1 and the Results section.

Figure S4. Electrochemical properties of 5-Me-PCA (A), 1-Me-PHZ (B), and SUL-PHZ (C). Related to Figure S5A and the Results section.

(A) Representative cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of samples with 5-Me-PCA (prepared from DKN370 culture extracts), without 5-Me-PCA (from PA14 wild-type culture extracts supplemented with PYO), and without phenazines (from PA14 Δphz culture extracts). Organic extracts were collected after incubating PA14 cultures on YPD plates for 4 days. Scan rate: 200 mV/s. See also Table S2 for all phenazine species concentrations in crude extracts. (B and C) Representative cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of 1-Me-PHZ and SUL-PHZ measured at different scan rates at pH 7.0 (left); the peak current vs. square root of voltage scan rate at pH 7.0 (middle); the mid-point potential (E1/2) vs. pH that are derived from CVs measured at different scan rates and pHs respectively (right). The CV test solutions were prepared by dissolving dried extracts, 54 μM 1-Me-PHZ, or 83 μM SUL-PHZ in 0.1 M KCl aqueous electrolyte buffered with 10 mM CH3C(O)ONH4–MOPS (5 mM each) in the pH range 4.2–8.0, or with 0.1 % formic acid (26.5 mM) at pH 2.6.

Figure S5. Hole diffusion assay to test PCA, SUL-PHZ, 1-OH-PHZ, PCN and 1-Me-PHZ effects on A. fumigatus (AF293 wild-type) development. Related to the Results section.

(A) Scanning images of plates were obtained for the hole-diffusion assay, after treating AF293 lawns for 6 days with a phenazine (I), or a phenazine together with the pH buffer MOPS (100 mM, pH 6.5 and 8.0) (II and III), ascorbic acid (AA, 100 mM) (IV), or H2O2 (10 mM) (V). (B) Scanning images of plates were obtained for the hole-diffusion assay after treated for 5 days with a phenazine (200 μM PCA, 200 μM SUL-PHZ, and 120 μM 1-OH-PHZ), or a phenazine together with the pH buffer formic acid (26.5 mM, pH 2.6). Water (i.e., no buffer), MOPS, AA, and H2O2, formic acid added alone served as the respective controls. Scale bar, 2.5 cm. Results are representative of biological triplicate experiments.

Figure S6. Gliotoxin can signal A. nidulans development under mildly reducing conditions through NapA oxidative stress regulation, as reflected by green conidial pigmentation. Related to Figure 5 and the Experimental Procedures section.

Scanning images of the plate region (illustrated in the top panel) for each A. nidulans (wild-type, napA deletion (ΔnapA) or overexpression (OE::napA)) strain were obtained after 4 days of treatment with no addition (i.e., water control), or with the addition of gliotoxin, ascorbic acid (AA) or gliotoxin together with AA. The gliotoxin suspension (200 μM) was applied homogeneously to the overlaying medium containing fungal conidia. The AA solution (100 mM) was applied to the treatment hole to create a redox gradient (distance from its application). Images are representative of biological triplicate experiments.

Table S1. Bacterial and fungal strains used in this study. Related to Figures 1–5.

Table S2. Concentrations of phenazine species in the crude extract samples. Related to Figures 2A, 2D; Figures 3A, 3B; Figures S4A.

Table S3. Redox potentials (E1/2) of phenazines in aqueous solution. Related to Figures 3D and S5A, and the Results section.

Table S4. Primers used in this study. Related to Figure 4E.