Abstract

Purpose

To estimate the effects of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations on ovarian cancer and breast cancer survival.

Experimental Design

We searched PUBMED and EMBASE for studies that evaluated the associations between BRCA mutations and ovarian or breast cancer survival. Meta-analysis was conducted to generate combined hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS).

Results

From 1201 unique citations, we identified 27 articles that compared prognosis between BRCA mutation carriers and non-carriers in ovarian or breast cancer patients. Fourteen studies examined ovarian cancer survival and 13 studies examined breast cancer survival. For ovarian cancer, meta-analysis demonstrated that both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers had better OS (HR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.70-0.83 for BRCA1 mutation carriers; HR: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.50-0.66 for BRCA2 mutation carriers) and PFS (HR: 0.65, 95% CI: 0.52-0.81 for BRCA1 mutation carriers; HR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.47-0.80 for BRCA2 mutation carriers) compared to non-carriers, regardless of tumor stage, grade, or histologic subtype. Among breast cancer patients, BRCA1 mutation carriers had worse OS (HR: 1.50, 95%CI: 1.11-2.04) than non-carriers, but were not significantly different from non-carriers in PFS. BRCA2 mutation was not associated with breast cancer prognosis.

Conclusions

Our analyses suggest that BRCA mutations are robust predictors of outcomes in both ovarian and breast cancer and these mutations should be taken into account when devising appropriate therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: BRCA, mutation, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, survival

Introduction

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are two distinct tumor suppressor genes that play an integral role in response to cellular stress via the activation of DNA repair processes.(1) Individuals with mutations in these two genes are at an increased risk of developing breast, ovarian, and other cancers. The lifetime risk of breast cancer among BRCA mutation carriers is 45-80% and for ovarian cancer, 45-60%.(2) Several studies have investigated prognoses among BRCA mutation carriers and non-carriers. Ovarian cancer patients with BRCA mutations have been reported to have better outcomes compared to non-carriers.(3-6) While other studies (7-10) demonstrated that outcomes were superior only among women with BRCA2 mutations. A recent study involving 873 patients did not find survival differences between BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers and non-carriers.(11)

Research on breast cancer prognoses and BRCA mutations has also yielded inconsistent results. Multiple studies have demonstrated that BRCA1-related breast cancers were more likely to be triple-negative, which was correlated with poor prognosis.(12-14) A meta-analysis published in 2010 also linked BRCA1 mutation to decreased overall and progression free survival among breast cancer patients although BRCA2 mutation was not associated with differential survival outcomes.(15) Additional studies, published since 2010, have generated varying results on the role of BRCA mutations in breast cancer prognoses. While a multi-country study failed to show differences in breast cancer survival rates associated with BRCA mutations,(16) Cortesi et al. (17) reported favorable 10-year breast cancer outcomes among BRCA1 carriers. Meanwhile, a large scale study involving 2967 patients demonstrated adverse effect of BRCA2 mutations on breast cancer specific survival.(18) These inconsistencies in the research may be due to variations in sample size and the relative rarity of mutation carriers.

Despite of our increased understanding of the pathophysiology of BRCA mutated cancers, specific treatments for these diseases have not yet been established. A novel class of anti-cancer agents, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, has shown strong activity in BRCA-related cancers by using the inherent HR (homologous recombination) defectiveness of these tumors.(19, 20) Enhanced understanding of the role of BRCA mutation status in ovarian and breast cancer survival will provide more accurate prognostic information, and can improve clinical decision-making with respect to trial design and cancer treatment. The objective of this study was to perform a meta-analysis to evaluate the effects of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations on overall and progression free survival of ovarian and breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

We followed the PRISMA Statement guidelines to design, analyze, and report our meta-analytic findings.(21) Only the study-level summery data was used for the analyses.

Literature Search

We reviewed PUBMED and EMBASE databases for articles published prior to Feb.10th, 2014. We identified studies by using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) including mutation, BRCA1, Genes, BRCA2, Survival, Prognosis, Ovarian Neoplasms, Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome, Ovarian epithelial cancer, Breast Neoplasms. These terms were also combined with keyword search and manual search of references in all selected studies.

Selection Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) comparison between breast or ovarian cancer patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and non-carriers confirmed by mutation analyses; (2) outcomes were survival related, such as overall survival or progression-free survival; (3) outcomes involved human subjects, and (4) published in English. In addition, articles were excluded if (1) control patients not confirmed of non-carriers; (2) review articles; (3) metastatic or recurrent cancer; (4) comparison were made between carriers or did not evaluate BRCA1 and 2 mutations separately; (5) studies for cancer specific survival only.

Study Selection, Data Extraction, and End Points

Initial screening of potentially eligible records was performed by two investigators (Q.Z, L.Z). Subsequent full-text record screening was performed independently by two investigators (Q.Z, WT.H). Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Baseline characteristics and outcomes were extracted from the selected articles. We chose OS (overall survival) and PFS (progression free survival) as our endpoints for meta-analysis, and treated disease free survival (DFS) as PFS. Various endpoints for PFS were reported in the selected breast cancer studies, including local recurrence free survival (LRFS),(22, 23) distant disease free survival(DDFS),(16, 23, 24) DFS,(17, 25, 26) metastasis-free survival (MFS) (22, 27) and contralateral recurrence free survival (CRFS).(23, 27) Because DDFS and MFS shared the same definition in these articles, we operationally defined PFS to include also MFS or DDFS for studies that did not provide DFS.

Quality Assessment

The quality of each study was independently rated by two investigators (Q.Z, WT.H), using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale(28) and Altman’s framework.(29)

Statistical Analysis

Hazard ratio (HR) was used as a measure of the prognostic value.HR > 1 indicated poor survival for the group with BRCA mutations. HRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were extracted from articles. For those studies in which HRs and CIs were not available, we used the method proposed by Parmar et al. to derive estimates from survival curves.(30) To improve accuracy, we excluded HRs derived from studies if the number of events in one group was less than five.(31, 32) Heterogeneity was assessed by Chi-square test and expressed by I2 index,(33) which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that are due to heterogeneity rather than chance (25% low heterogeneity, 50% medium, 75% high). Random effects models were initially used to obtain the summary HRs and 95% CIs, and if there was no heterogeneity among studies, fixed effects models were employed to estimate pooled HRs.(34) If results of both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were reported, we chose multivariate models for a more accurate estimate of the effect of BRCA mutation. Subgroup analyses were performed based on variables including stage, grade, histologic subtype, optimal debulking rate, tumor size, nodal status, ER status, chemotherapy and hormone therapy rates, and whether a multivariate or univariate Cox regression was used. Publication bias was assessed by inspecting the symmetry of the funnel plot and tested with Begg’s and Egger’s tests.(35, 36) STATA 12.0. was used to test for publication bias. All other analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.2.

Results

Identification of Relevant Studies

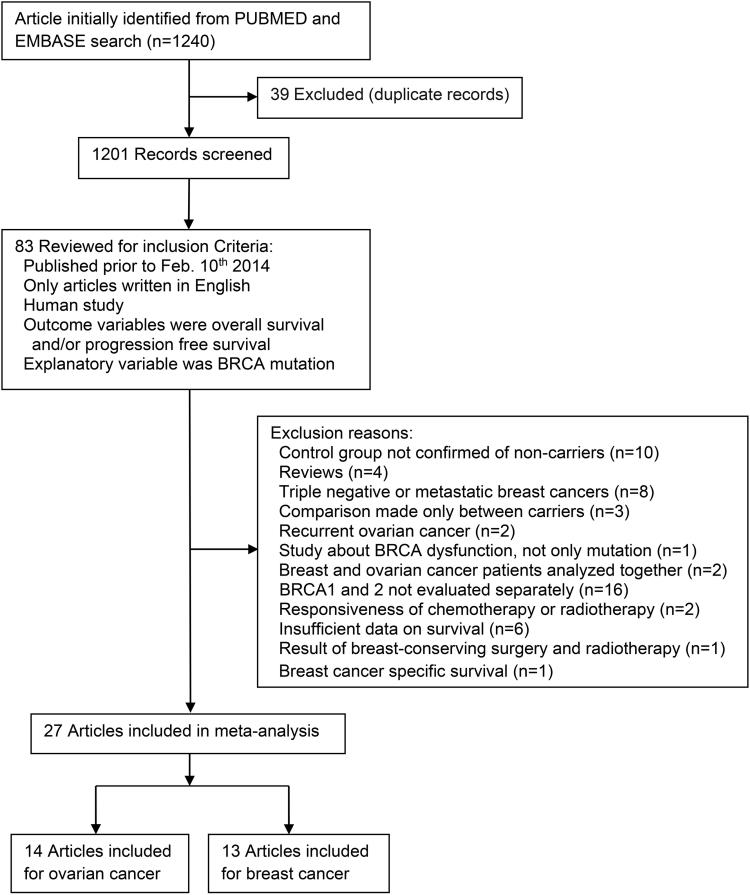

Figure 1 summarized the identification of relevant studies. We screened 1201 articles for eligibility and identified 27studies (including two related publications from the same study (13, 26)) for meta-analysis. Among them, 20 were retrospective cohort studies, 7 were prospective cohort studies. The research quality among the selected studies was high; with a median quality score of 0.86 (range 0.67 to 0.92).

Fig.1.

Flow diagram for selection of studies

Study Characteristics

Ovarian cancer studies

Fourteen studies were included in the meta-analysis of ovarian cancer. Characteristics of ovarian cancer patient cohorts are presented in Table 1.The studies were conducted in eight countries (Poland, Italy, Israel, UK, Canada, USA, Hong Kong and Australia) and published between 1999 and 2014. The median number of women evaluated per study was 251(range 48 to 3879), with a total of 9588 patients, including 1722 BRCA1 mutation carriers, 659 BRCA2 mutation carriers, and 7207 non-carriers. The reported mean or median age for studies was similar, ranging from 54.4 to 65.4 years. The percentage of women with serous tumors varied from 31% to 100%, with two studies focused exclusively on serous cancers.(8, 9) Between 62% and 100% of patients had stage III-IV diseases, while 12% to 100% of patients had grade 3 tumors. Optimal debulking rate varied from 51%-89%, but data was missing in 8 studies. (3, 4, 7, 10, 37-40) Eight studies (3-5, 7, 10, 11, 37, 41) reported median or mean follow-up time, ranging from 1.5 to 6.9 years. Ten studies (71%) (3-11, 37) conducted a multivariate analysis to adjust for confounding variables such as age, stage, debulking status, cancer or family history, menopausal status, grade, histology, platinum sensitivity, year of diagnosis, or morphology. The most commonly used BRCA mutation detecting methods were PCR and sequencing in selected studies. BRCA associated ovarian cancers were more likely to be characterized by high-grade serous histology and advanced stage. Based on 7 out of 14 ovarian cancer studies that had mean age data available, we found that the mean ages for the mutation groups appeared to be younger, particularly for BRCA1 mutation carriers: 43 years and 47 years old for BRCA1, and BRCA2 carriers respectively, compared to 49 years old for non-carriers. (Supplementary Table S1)

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies for ovarian cancer.

| Author (Year) | Country | Number of subject |

Mean or median /SD or Range of Age (Yr) |

Median/Range of follow-up (Yr) |

Serous cancer (%) |

Stage III-IV (%) |

Grade 3 (%) |

Optimal debulking(%) |

Quality score |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1+ | BRCA2+ | Non-carrier | |||||||||

| Cunningham(11)2014 | USA | 30 | 27 | 816 | 62.4±11.7 | 4.5(0.01-10) | 73 | 80 | 86 | 85 | 0.83 |

| Safra(4)2013 | Israel, USA, Italy | 71 | 19 | 100 | 55.5d(31-83) | 4.7(0.8-17.8) | 69.5 | 88.9 | NR | NR | 0.92 |

| McLaughlin(7)2013 | Canada, USA | 129 | 89 | 1408 | 57.2(19-81) | 6.9e(0.3-12) | 55.8 | 64.6 | 35.1 | NR | 0.88 |

| Alsop(5)2012 | Australia | 88 | 53 | 777 | 59.8±10.4 | 5.3(NA) | 70.8 | 67.8 | 56.6 | 62.4 | 0.92 |

| Hyman(8)2012 | USA | 30 | 17 | 143 | 58.5d(32-78) | NR | 100 | 100 | 100 | 76.3 | 0.88 |

| Bolton(3)2012a | Multi-country | 909 | 304 | 2666 | 56.8±11.4 | 3.2(1.5-6.9) | 67 | 61.6 | 72.2 | NR | 0.88 |

| Yang(9)2011 | USA | 35 | 27 | 219 | 60.6±0.7 | NR | 100 | 96 | 91 | 75 | 0.88 |

| Chetrit(37)2008b | Israel | 159 | 54 | 392 | NR | 6.2(4.2-9.4) | 58.7 | 100 | 59 | NR | 0.88 |

| Pal(10)2007 | USA | 20 | 12 | 200 | 56.7(18-80) | 1.5(NR) | 58.2 | 70.7 | NR | NR | 0.83 |

| Majdak(6)2005 | Poland | 18 | NA | 171 | NRc | NR | 64.6 | 87.8 | 12.1 | 88.9 | 0.92 |

| Buller(38)2002 | USA | 24 | NA | 24 | 59.4(55.3-63.1) | NR | 74.6 | 86.4 | 66.1 | NR | 0.71 |

| Ramus(39)2001 | Israel | 15 | 12 | 71 | 65.4d(32-88) | NR | 77.6 | 82.7 | 50.5 | NR | 0.71 |

| Boyd(41)2000 | USA | 67 | 21 | 101 | 59.7±11.5 | 4.8(NR) | 64 | 95.8 | 78.8 | 50.8 | 0.75 |

| Pharoah(40)1999 | UK | 127 | 24 | 119 | 54.4(NR) | NR | 31 | 83 | 24.7 | NR | 0.71 |

This study was conducted in USA, Europe, Israel, Hong Kong, Canada, Australia and UK.

For article written by Chetritet al., we chose the results of a subgroup of patients with Ashkenazi Jewish origin and stage III-IV tumors whose survival data was analyzed by multivariate analysis. This study only provided percentage of age period: 24% of patients were under 50.

Majdak et al., 39% of patients were under 50.

Median age.

Mean follow up time.

NR: Not reported, NA: not applicable.

Breast cancer studies

Thirteen studies were included in the meta-analysis of breast cancer. Characteristics of breast cancer patient cohorts are presented in Table 2. The studies were conducted in 12 countries (Poland, Italy, Israel, Norway, UK, Netherlands, Canada, France, Finland, USA, Australia and Germany) and published between 2000 and 2013. A total of 10,016 patients (ranging from 85 to 3345 per study) were included, among them were 890 BRCA1 mutation carriers, 342 BRCA2 mutation carriers, and 8784 non-carriers. The reported mean or median age ranged from 42.6 to 62.1 years across eligible studies. The percentage of women with tumor >2cm varied from 9% to 66%, with 0-49% nude positive, 23-49% grade 3 tumors, 37-67% ER positive,25-72% receiving chemotherapy and 19-56% receiving hormone therapy. Among the nine studies(12, 13, 16, 17, 22-25, 27) that reported median or mean follow-up time, the median duration was 6.3, ranging from 4.5 to 7.9 years. Nine studies (12, 13, 16, 17, 22, 24, 42-44)(69%) conducted a multivariate analysis of HRs to adjust for age, tumor size, nodal or ER status, oophorectomy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, year of diagnosis, or nuclear grade. PCR and sequencing were the most commonly utilized BRCA mutation detecting methods across selected studies. After analyzing data from 6 studies (5 for BRCA2) out of 13 breast cancer studies that had mean age data available, we found that BRCA mutation carriers were comparatively younger in age, particularly for BRCA1 mutation carriers. The mean age of BRCA1 mutation carriers was 52 years, and 54 years for BRCA2 mutation carriers, compared to 58 years for non-carriers. Furthermore, BRCA1 mutation carriers were more likely to be ER and PR negative, have lower histological grade and receive chemotherapy. (Supplementary Table S2)

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies for breast cancer.

| Author (year) | Country | Number of subject |

Mean or median /SD or Range of Age (Yr) |

Median/ Range of follow-up (Yr) |

Tumor size>2cm (%) |

Node positive (%) |

Grade3 (%) |

ER+ (%) |

Chemo- therapy(%) |

Hormone therapy(%) |

Quality score |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1+ | BRCA2+ | Non-carrier | |||||||||||

| Huzarski(12)2013 | Poland | 233 | NA | 3112 | 43.9(21-50) | 7.4f(0.1-15.8) | 41.4 | 49.2 | NR | 58.7 | 72.1 | 40.6 | 0.92 |

| Goodwin(16)2012a | Multi-country | 94 | 72 | 1550 | 45.3±9.8 | 7.9(NR) | 38.7 | 39.7 | 43.1 | 66.7 | 62.2 | 44.8 | 0.92 |

| Cortesi(17)2010 | Italy | 80 | NA | 931 | NR | 6(NR) | 53.1 | NR | NR | 65.5 | 38.9 | 55.5 | 0.79 |

| Budroni(42)2009 | Italy | NA | 44 | 464 | NRe | NR | 9 | 44 | NR | 74 | NR | NR | 0.88 |

| Rennert(43)2007b | Israel | 76 | 52 | 1189 | 62.1±13.5 | NR | 66 | 47 | NR | 63 | 25.1 | NR | 0.88 |

| Moller(14)2007 | Norway, UK | 89 | 35 | 318 | 48.8(NR) | NR | NR | 23 | 49 | 57 | NR | NR | 0.67 |

| Brekelmans(23)2007 | Netherlands | 170 | 90 | 238 | 44.8(23-85) | 4.5(0.2-24.5) | 40.4 | 44.1 | 46.6 | 43 | 45.2 | 18.9 | 0.92 |

| Bonadona(27)2007 | France | 15 | 6 | 211 | NRe | 6.8(0.1-9.3) | NR | 40.5 | 36.3 | 53 | 56.9 | 26.3 | 0.83 |

| Goffin(24)2003 | Canada | 30 | NA | 248 | 53.4g(27-65) | 8(NR) | NR | 44 | 33 | 63 | 47 | 50 | 0.92 |

| Eerola(44)2001 | Finland | 32 | 43 | 284 | NRe | NR | NR | NR | NR | NA | NR | NR | 0.83 |

| Stoppa-Lyonnet(22)2000c | France | 19 | NA | 91 | 42.6±10.2 | 4.8(0.5-17.5) | 56.8 | 28.1 | 23.4 | 36.5 | NR | NR | 0.83 |

| Hamann(25)2000 | Germany | 36 | NA | 49 | 43g(19-73) | 5.6(NR) | 37.6 | 32.9 | 23.5 | NA | NR | NR | 0.75 |

| Foulkes(13)2000d | Canada | 16 | NA | 99 | 53.9g(28-65) | 6.3(0.8-11.1) | NR | 0 | 33 | 59.1 | 35.7 | NR | 0.83 |

This study was conducted in Canada, USA and Australia.

For article written by Rennert et al., we chose a subgroup of patients of Ashkenazi Jewish origin whose survival data was analyzed by multivariate analysis.

For article written by Stoppa-Lyonnet et al., we chose the results of a subgroup of patients with<36 months interval between diagnosis and genetic counseling whose survival data was analyzed by multivariate analysis.

Budroni et al., 42% of patients were under 40. Bonadona et al., 50% of patients were under 40. Eerola et al., 36% of patients were under 50.

Mean follow up time.

Median age.

NR: Not reported, NA: not applicable.

Prognostic value of BRCA mutations on ovarian and breast cancer

Ovarian cancer prognosis

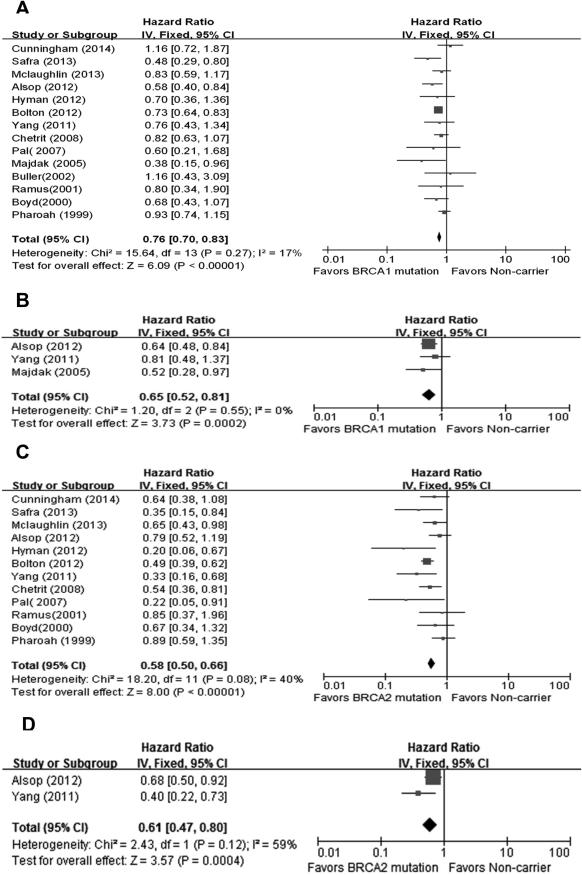

Fourteen studies were included in the analysis of the effect of BRCA1 mutation on ovarian cancer OS. The results of our meta-analysis showed that BRCA1 mutation carriers were associated with better OS than non-carriers, with a pooled HR of 0.76(95%CI, 0.70-0.83). No significant heterogeneity was found across the studies (I2=17%, P=0.27). A stronger effect was found using twelve studies assessing OS between BRCA2 carriers and non-carriers. BRCA2 mutation carriers were associated with even better OS compared to non-carriers, with a pooled HR of 0.58 (95%CI, 0.50-0.66).There was an indication of slight heterogeneity across the studies, but it did not reach statistical significance (I2=40%, P=0.08). Associations between BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and ovarian cancer PFS were also evaluated, respectively. Meta-analyses results (3 studies for BRCA1 mutation, 2 studies for BRCA2 mutation) demonstrated that both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers were associated with better PFS than non-carriers, with pooled HR of 0.65 (95%CI, 0.52-0.81) for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 0.61 (95%CI, 0.47-0.80) for BRCA2 mutation carriers. No significant heterogeneity was found across the studies (I2=0% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and I2=59% for BRCA2 mutation carriers, all P>0.10). (Figure 2)

Fig.2.

Forest plots of associations between BRCA mutations and ovarian cancer survival.(A) Effect of BRCA1 mutation on OS,(B) Effect of BRCA1 mutation on PFS,(C) Effect of BRCA2 mutation on OS,(D) Effect of BRCA2 mutation on PFS.

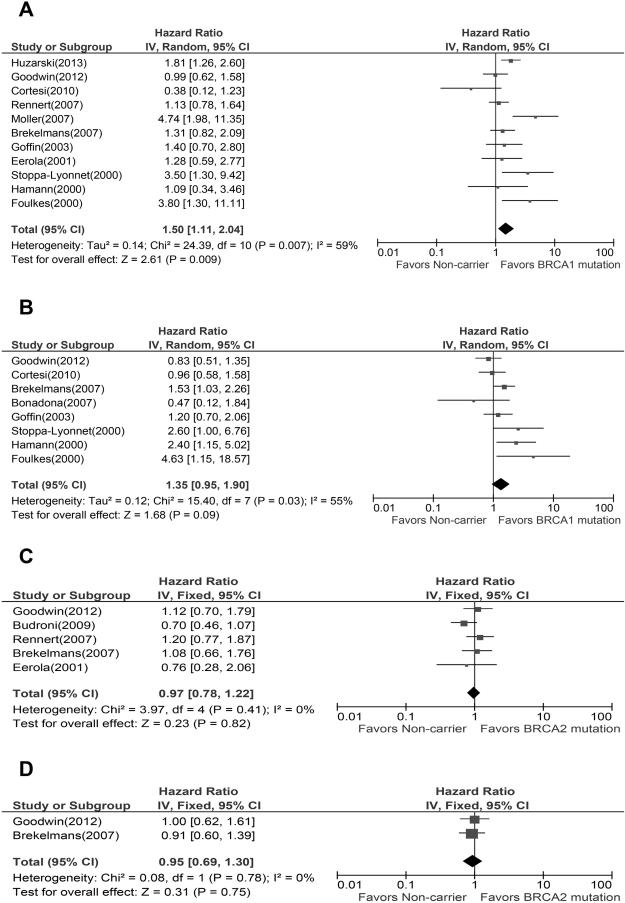

Breast cancer prognosis

Meta-analysis of eleven studies showed a worse breast cancer OS among BRCA1 mutation carriers compared to non-carriers. Because a significant heterogeneity was found across the studies (I2=59%, P=0.007), the pooled HR of 1.5(95%CI, 1.11-2.04) was calculated based upon a random effects model. The result of meta-analysis of five studies comparing breast cancer OS between BRCA2 carriers and non-carriers, indicated no association between mutation and OS, with a pooled HR of 0.97(95%CI, 0.78-1.22), and no significant heterogeneity was found across the studies (I2=0%). Eight studies and two studies were included to assess the association between BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and breast cancer PFS, respectively. Meta-analyses results did not reveal any association between these two mutations and PFS, with a pooled HR of 1.35 (95%CI, 0.95-1.90) for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 0.95 (95%CI, 0.69-1.30) for BRCA2 mutation carriers. A random effects model was used for the BRCA1 mutation meta-analysis due to a significant heterogeneity among studies (I2=55%, P=0.03). No significant heterogeneity among studies was found in the meta-analysis of BRCA2 mutation (I2=0%). (Figure 3)

Fig.3.

Forest plots of associations between BRCA mutations and breast cancer survival. (A) Effect of BRCA1 mutation on OS, (B) Effect of BRCA1 mutation on PFS, (C) Effect of BRCA2 mutation on OS, (D) Effect of BRCA2 mutation on PFS.

Subgroup analysis of effect of BRCA mutations on ovarian and breast cancer OS

Subgroup analysis was conducted to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity among studies and to assess the consistency of conclusions among different subpopulations of patients.

Ovarian cancer subgroup analysis

For ovarian cancer, BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers have significantly longer OS than non-carriers, regardless of tumor stage, grade, or histologic subtype.

Breast cancer subgroup analysis

The results of subgroup analyses for BRCA1 mutation in breast cancer outcomes were less consistent due to the limited number of studies available. Interestingly, a subgroup of studies employing multivariate analysis showed that BRCA1 mutation carriers had borderline poorer breast cancer OS (HR,1.40; 95%CI, 1.00-1.98; P=0.05) than non-carriers, while studies involving univariate analysis yielded no association between BRCA1 mutation and breast cancer OS.(Table 3)

Table 3.

Associations between BRCA mutation and OS grouped by selected factors.

| Comparison | No. of studies |

No. of patients |

Hazard ratio(95%CI) | Consistency | Overall effects P value |

I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian cancer overall survival | ||||||

| BRCA1+ VS. Non-carrier | ||||||

| Multivariate analysis | 10 | 8965 | 0.73 [0.67, 0.81] | Consistent | <0.00001 | 19% |

| Univariate analysis | 4 | 605 | 0.88 [0.73, 1.06] | Inconsistent | 0.18 | 0% |

| Stage III-IV tumor ≥80% | 10 | 2933 | 0.82 [0.72, 0.93] | Consistent | 0.003 | 22% |

| Stage III-IV tumor <80% | 4 | 6655 | 0.72 [0.64, 0.81] | Consistent | <0.00001 | 0% |

| Serous tumor ≥70% | 6 | 2408 | 0.77 [0.61, 0.97] | Consistent | 0.03 | 14% |

| Serous tumor <70% | 8 | 7180 | 0.76 [0.69, 0.84] | Consistent | <0.00001 | 29% |

| Grade3 tumor ≥70% | 5 | 5034 | 0.75 [0.66, 0.84] | Consistent | <0.00001 | 0% |

| Grade3 tumor<70% | 7 | 3754 | 0.81 [0.71, 0.9S] | Consistent | 0.003 | 21% |

| Optimal debulking rate ≥75% | 4 | 1533 | 0.82 [0.61, 1.11] | Inconsistent | 0.21 | 39% |

| Optimal debulking rate <75% | 2 | 1107 | 0.62 [0.46, 0.82] | Consistent | 0.001 | 0% |

| BRCA2+ VS. Non-carrier | ||||||

| Multivariate analysis | 9 | 8776 | 0.53 [0.46, 0.62] | Consistent | <0.00001 | 32% |

| Univariate analysis | 3 | 557 | 0.83 [0.60, 1.15] | Inconsistent | 0.26 | 0% |

| Stage III-IV tumor ≥80% | 8 | 2696 | 0.60 [0.49, 0.74] | Consistent | <0.00001 | 41% |

| Stage III-IV tumor <80% | 4 | 6655 | 0.56 [0.47, 0.67] | Consistent | <0.00001 | 50% |

| Serous tumor ≥70% | 5 | 2360 | 0.62 [0.47, 0.81] | Consistent | 0.0005 | 51% |

| Serous tumor <70% | 7 | 6991 | 0.56 [0.48, 0.66] | Consistent | <0.00001 | 38% |

| Grade3 tumor ≥70% | 5 | 5034 | 0.50 [0.41, 0.60] | Consistent | <0.00001 | 21% |

| Grade3 tumor<70% | 5 | 3517 | 0.71 [0.58, 0.87] | Consistent | 0.0008 | 0% |

| Optimal debulking rate ≥75% | 3 | 1344 | 0.46 [0.31, 0.69] | Consistent | 0.0001 | 52% |

| Optimal debulking rate <75% | 2 | 1107 | 0.75 [0.53, 1.07] | Inconsistent | 0.12 | 0% |

| Breast cancer overall survival | ||||||

| BRCA1+ VS. Non-carrier | ||||||

| Multivariate analysis | 8 | 8251 | 1.40 [1.00, 1.98] | Consistent | 0.05 | 58% |

| Univariate analysis | 3 | 1025 | 1.89 [0.79, 4.52] | Inconsistent | 0.15 | 71% |

| Tumor >2cm proportion ≥10% | 6 | 7997 | 1.29 [0.91, 1.84] | Inconsistent | 0.15 | 62% |

| Tumor >2cm proportion <10% | 1 | 85 | 1.09 [0.34, 3.46] | Inconsistent | 0.88 | NA |

| Node positive tumor ≥25% | 7 | 7349 | 1.37 [1.07, 1.75] | Consistent | 0.01 | 32% |

| Node positive tumor <25% | 2 | 557 | 4.34 [2.20, 8.54] | Consistent | <0.00001 | 76% |

| Grade3 tumor ≥25% | 5 | 3049 | 1.78 [1.05, 3.01] | Consistent | 0.03 | 69% |

| Grade3 tumor <25% | 2 | 195 | 2.13 [1.01, 4.53] | Consistent | 0.05 | 56% |

| ER(+) tumor ≥50% | 7 | 8224 | 1.50 [0.98, 2.30] | Inconsistent | 0.06 | 71% |

| ER(+) tumor <50% | 2 | 608 | 1.57 [1.03, 2.39] | Consistent | 0.04 | 68% |

| Chemotherapy rate ≥50% | 2 | 5061 | 1.36 [0.76, 2.46] | Inconsistent | 0.3 | 75% |

| Chemotherapy rate <50% | 5 | 3219 | 1.24 [0.96, 1.59] | Inconsistent | 0.10 | 53% |

| Hormone therapy rate ≥40% | 4 | 6350 | 1.17 [0.71, 1.92] | Inconsistent | 0.55 | 65% |

| Hormone therapy rate <40% | 1 | 498 | 1.31 [0.82, 2.09] | Inconsistent | 0.25 | NA |

| BRCA2+ VS. Non-carrier | ||||||

| Multivariate analysis | 4 | 3900 | 0.95 [0.74, 1.22] | Consistent | 0.68 | 20% |

| Univariate analysis | 1 | 498 | 1.08 [0.66, 1.76] | Consistent | 0.53 | NA |

| Tumor >2cm proportion ≥10% | 3 | 3531 | 1.14 [0.87, 1.49] | Consistent | 0.35 | 0% |

| Tumor >2cm proportion <10% | 1 | 508 | 0.70 [0.46, 1.07] | Consistent | 0.1 | NA |

| Node positive tumor ≥25% | 4 | 4039 | 0.99 [0.79, 1.24] | Consistent | 0.91 | 20% |

| Node positive tumor <25% | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Grade3 tumor ≥25% | 2 | 2214 | 1.10 [0.78, 1.55] | Consistent | 0.58 | 0% |

| Grade3 tumor <25% | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| ER(+) tumor ≥50% | 3 | 3541 | 0.96 [0.75, 1.24] | Consistent | 0.77 | 44% |

| ER(+) tumor <50% | 1 | 498 | 1.08 [0.66, 1.76] | Consistent | 0.53 | NA |

| Chemotherapy rate ≥50% | 1 | 1716 | 1.12 [0.70, 1.79] | Consistent | 0.64 | NA |

| Chemotherapy rate <50% | 2 | 1815 | 1.14 [0.82, 1.59] | Consistent | 0.42 | 0% |

| Hormone therapy rate ≥40% | 1 | 1550 | 1.12 [0.70, 1.79] | Consistent | 0.64 | NA |

| Hormone therapy rate <40% | 1 | 498 | 1.08 [0.66, 1.76] | Consistent | 0.76 | NA |

Publication bias

Formal investigation using Begg’s test and Egger’s test indicated no publication bias in the meta-analyses for associations of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation with ovarian cancer OS, and BRCA1 mutation with breast cancer OS and PFS. We did not test publication bias for the meta-analyses of ovarian cancer PFS, and breast cancer OS and PFS for BRCA2 mutation because too few studies were available to make a valid statistical test. (Supplementary Figure S1)

Discussion

This is the first meta-analysis that investigated both ovarian and breast cancer survival in patients with BRCA1 or 2 mutations compared to non-carriers in one report. Our results demonstrated that BRCA mutations had a differential impact on ovarian and breast cancer survival. Both BRCA1 and 2 mutations were positively associated with ovarian cancer OS and PFS, and BRCA2 mutation appeared to have a greater effect upon OS, regardless of tumor stage, grade, or histologic subtype. In breast cancer outcomes, the impact of BRCA mutations was just the opposite. BRCA1 mutation carriers had worse prognoses than non-carriers for OS, but were not different from non-carriers in PFS. BRCA2 mutation was not associated with breast cancer prognosis.

Our results, with respect to ovarian cancer overall survival were consistent with the previous meta-analysis by Sun C et al.(45). For ovarian cancer PFS, although Sun et al. did not separate BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in their analysis, they still found a favorable PFS in BRCA1/2 mutations carriers, which was consistent with our finding. After incorporating four additional studies(12, 16, 17, 27) into our meta-analysis, our breast cancer OS results were also consistent with the previous meta-analysis published by Lee et al.,(15) but we did not replicate their findings on the effect of BRCA1 mutation on breast cancer PFS. We believed that it may be due to the fact that Lee et al. had analyzed short-term (i.e., less than 5 years) and long-term (i.e., more than 5 five years) PFS separately and fewer number of studies were analyzed.

At this time, the mechanism driving the association between BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation and survival is not clear. It may be rooted in different functions of the BRCA genes in the dsDNA-repair pathway. As we know, postoperative platinum based chemotherapy is the main treatment for ovarian cancer. Most studies suggested that the ovarian cancer survival advantage observed among BRCA carriers could be mediated through improved response to platinum based agents, due to an impaired ability to repair double stranded DNA breaks through homologous recombination.(46)The fact that BRCA2 mutation improved ovarian cancer survival may be due to the gene’s more direct involvement in homologous recombination which can attenuate or abolish the interaction with RAD51, resulting in failure to load RAD51 to DNA-damage sites. The BRCA1 mutation may have less impact on RAD51-mediated homologous recombination which could account for the disparity in outcomes between BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. (47, 48) For breast cancer, we often rely upon different types of treatments including hormone therapy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. Research on breast cancer also indicated that BRCA1 mutation carriers had more p53 mutations resulting in worse prognosis.(49) The different breast cancer outcomes observed among BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers could also be due to their distinct clinical characteristics. As mentioned previously, BRCA1-related breast cancers were more likely to be triple-negative, which made treatment more difficult.

Certain limitations must be considered when interpreting study findings. First, our meta-analysis only encompassed a total of 27 studies. Studies specific to BRCA2 mutations for breast cancer were less common in the literature and are therefore underrepresented in this analysis. The limited availability of BRCA2 mutation studies complicated our ability to test publication bias. This is partially due to the fact that we excluded a number of studies which did not evaluate BRCA1 and 2 separately or compared mutation carriers to sporadic cancer patients without testing mutation status on control patients. Second, due to the variety of endpoints reported in breast cancer studies, we operationally defined breast cancer PFS to include MFS or DDFS for studies that did not provide DFS and had to exclude LRFS and CRFS results(which were considered to be parts of PFS for some studies) from a few studies. Third, most of studies were focused on western population; only one study included Asian women.(3)Additional studies are needed to better understand the effects of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations on survival among carriers in Asian and for other ethnicity or geographic regions. Finally, nearly half of the studies selected for our breast cancer meta-analysis failed to provide sufficient data on patient characteristics which may have impacted the validity of subgroup analysis.

Despite these limitations, our meta-analysis rigorously evaluated the effects of BRCA1 and 2 mutations on both ovarian and breast cancer survival using all eligible studies in the same setting and had performed intensive subgroup analyses. Our results may have important implications for the clinical management of both ovarian and breast cancer. The results can be used immediately by health care professionals for patients counseling regarding expected survival. Also, there is a widespread agreement that PARP inhibitors (PARPi) can effect on BRCA-related cancers by using the inherent HR defectiveness of the tumors in a synthetically lethal manner. Many phase I and II trials have reported the successful applications of PARP inhibitors in ovarian and breast cancer patients with BRCA mutations, and phase III trials are under way. (19, 20, 50) Given the prognostic information provided by different BRCA status and the possibility for personalized treatments in carriers and non-carriers, the next step would be to see how this knowledge can be used to optimize treatments and testing targeted therapy in the future. The design of upcoming clinical trials could be stratified by BRCA status to avoid potential bias introduced by unequal numbers of carriers in treatment groups or between study cohorts. Routine testing of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation status of ovarian cancer and BRCA1 mutation status of breast cancer may now be warranted.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

This report compiles data from fourteen studies of 9,588 women with ovarian cancer, and thirteen studies of 10,016 women with breast cancer and confirms the positive prognostic effect of both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations on ovarian cancer overall and progression free survival, and adverse prognostic effect of BRCA1 mutation on breast cancer overall survival. The results can be used immediately by health care professionals for patients counseling regarding expected survival. In addition, stratification by BRCA status should be considered for cancer treatments and the design of clinical trials for targeted therapy.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health (P50-CA83638 to W-T. Hwang and L. Zhang; R01-CA142776 to L. Zhang); Department of Defense (W81XWH-10-1-0082 to L. Zhang); Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (to L. Zhang); the Basser Research Center for BRCA grant (to L. Zhang); and Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research grant (to L. Zhang). Q. Zhong was supported by a scholarship from Sichuan University and National Natural Science Foundation of China (0040215401068).

Footnotes

AUTHOR’S DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moynahan ME, Chiu JW, Koller BH, Jasin M. Brca1 controls homology-directed DNA repair. Mol Cell. 1999;4:511–8. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orban TI, Olah E. Emerging roles of BRCA1 alternative splicing. Molecular pathology : MP. 2003;56:191–7. doi: 10.1136/mp.56.4.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolton KL, Chenevix-Trench G, Goh C, Sadetzki S, Ramus SJ, Karlan BY, et al. Association between BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and survival in women with invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2012;307:382–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safra T, Lai WC, Borgato L, Nicoletto MO, Berman T, Reich E, et al. BRCA mutations and outcome in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC): experience in ethnically diverse groups. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2013;24(Suppl 8):viii63–viii8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, deFazio A, Emmanuel C, George J, et al. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:2654–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Majdak EJ, Debniak J, Milczek T, Cornelisse CJ, Devilee P, Emerich J, et al. Prognostic impact of BRCA1 pathogenic and BRCA1/BRCA2 unclassified variant mutations in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:1004–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLaughlin JR, Rosen B, Moody J, Pal T, Fan I, Shaw PA, et al. Long-term ovarian cancer survival associated with mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:141–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyman DM, Zhou Q, Iasonos A, Grisham RN, Arnold AG, Phillips MF, et al. Improved survival for BRCA2-associated serous ovarian cancer compared with both BRCA-negative and BRCA1-associated serous ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:3703–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang D, Khan S, Sun Y, Hess K, Shmulevich I, Sood AK, et al. Association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with survival, chemotherapy sensitivity, and gene mutator phenotype in patients with ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2011;306:1557–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal T, Permuth-Wey J, Kapoor R, Cantor A, Sutphen R. Improved survival in BRCA2 carriers with ovarian cancer. Familial Cancer. 2007;6:113–9. doi: 10.1007/s10689-006-9112-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunningham JM, Cicek MS, Larson NB, Davila J, Wang C, Larson MC, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Ovarian Cancer Classified by BRCA1, BRCA2, and RAD51C Status. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4026. doi: 10.1038/srep04026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huzarski T, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Gorski B, Domagala P, Cybulski C, et al. Ten-year survival in patients with BRCA1-negative and BRCA1-positive breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:3191–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.3571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foulkes WD, Chappuis PO, Wong N, Brunet JS, Vesprini D, Rozen F, et al. Primary node negative breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers has a poor outcome. Annals of Oncology. 2000;11:307–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1008340723974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moller P, Evans DG, Reis MM, Gregory H, Anderson E, Maehle L, et al. Surveillance for familial breast cancer: Differences in outcome according to BRCA mutation status. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;121:1017–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee EH, Park SK, Park B, Kim SW, Lee MH, Ahn SH, et al. Effect of BRCA1/2 mutation on short-term and long-term breast cancer survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:11–25. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0859-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodwin PJ, Phillips KA, West DW, Ennis M, Hopper JL, John EM, et al. Breast cancer prognosis in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: an International Prospective Breast Cancer Family Registry population-based cohort study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:19–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cortesi L, Masini C, Cirilli C, Medici V, Marchi I, Cavazzini G, et al. Favourable ten-year overall survival in a Caucasian population with high probability of hereditary breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tryggvadottir L, Olafsdottir EJ, Olafsdottir GH, Sigurdsson H, Johannsson OT, Bjorgvinsson E, et al. Tumour diploidy and survival in breast cancer patients with BRCA2 mutations. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;140:375–84. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2637-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:123–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Audeh MW, Carmichael J, Penson RT, Friedlander M, Powell B, Bell-McGuinn KM, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:245–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60893-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Ansquer Y, Dreyfus H, Gautier C, Gauthier-Villars M, Bourstyn E, et al. Familial invasive breast cancers: worse outcome related to BRCA1 mutations. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18:4053–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.24.4053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brekelmans CT, Tilanus-Linthorst MM, Seynaeve C, vd Ouweland A, Menke-Pluymers MB, Bartels CC, et al. Tumour characteristics, survival and prognostic factors of hereditary breast cancer from BRCA2-, BRCA1- and non-BRCA1/2 families as compared to sporadic breast cancer cases. European Journal of Cancer. 2007;43:867–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goffin JR, Chappuis PO, Begin LR, Wong N, Brunet JS, Hamel N, et al. Impact of germline BRCA1 mutations and overexpression of p53 on prognosis and response to treatment following breast carcinoma: 10-year follow up data. Cancer. 2003;97:527–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamann U, Sinn HP. Survival and tumor characteristics of German hereditary breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;59:185–92. doi: 10.1023/a:1006350518190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foulkes WD, Wong N, Brunet JS, Begin LR, Zhang JC, Martinez JJ, et al. Germ-line BRCA1 mutation is an adverse prognostic factor in Ashkenazi Jewish women with breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 1997;3:2465–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonadona V, Dussart-Moser S, Voirin N, Sinilnikova OM, Mignotte H, Mathevet P, et al. Prognosis of early-onset breast cancer based on BRCA1/2 mutation status in a French population-based cohort and review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;101:233–45. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D'Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health technology assessment. 2003;7:iii–x. doi: 10.3310/hta7270. 1-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altman DG. Systematic reviews of evaluations of prognostic variables. BMJ. 2001;323:224–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7306.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parmar MKB, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:2815–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981230)17:24<2815::aid-sim110>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Tamer M, Russo D, Troxel A, Bernardino LP, Mazziotta R, Estabrook A, et al. Survival and recurrence after breast cancer in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2004;11:157–64. doi: 10.1245/aso.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armakolas A, Ladopoulou A, Konstantopoulou I, Pararas B, Gomatos IP, Kataki A, et al. BRCA2 gene mutations in Greek patients with familial breast cancer. Human Mutation. 2002;19:81–2. doi: 10.1002/humu.9003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in medicine. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chetrit A, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, Ben-David Y, Lubin F, Friedman E, Sadetzki S. Effect of BRCA1/2 mutations on long-term survival of patients with invasive ovarian cancer: the national Israeli study of ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:20–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.6905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buller RE, Shahin MS, Geisler JP, Zogg M, De Young BR, Davis CS. Failure of BRCA1 dysfunction to alter ovarian cancer survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramus SJ, Fishman A, Pharoah PD, Yarkoni S, Altaras M, Ponder BA. Ovarian cancer survival in Ashkenazi Jewish patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:278–81. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2000.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pharoah PD, Easton DF, Stockton DL, Gayther S, Ponder BA. Survival in familial, BRCA1-associated, and BRCA2-associated epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:868–71. United Kingdom Coordinating Committee for Cancer Research (UKCCCR) Familial Ovarian Cancer Study Group. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyd J, Sonoda Y, Federici MG, Bogomolniy F, Rhei E, Maresco DL, et al. Clinicopathologic features of BRCA-linked and sporadic ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2000;283:2260–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Budroni M, Cesaraccio R, Coviello V, Sechi O, Pirino D, Cossu A, et al. Role of BRCA2 mutation status on overall survival among breast cancer patients from Sardinia. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rennert G, Bisland-Naggan S, Barnett-Griness O, Bar-Joseph N, Zhang S, Rennert HS, et al. Clinical outcomes of breast cancer in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:115–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eerola H, Vahteristo P, Sarantaus L, Kyyronen P, Pyrhonen S, Blomqvist C, et al. Survival of breast cancer patients in BRCA1, BRCA2, and non-BRCA1/2 breast cancer families: a relative survival analysis from Finland. International Journal of Cancer. 2001;93:368–72. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun C, Li N, Ding D, Weng D, Meng L, Chen G, et al. The role of BRCA status on the prognosis of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014;9:e95285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hyman DM, Spriggs DR. Unwrapping the implications of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2012;307:408–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu G, Yang D, Sun Y, Shmulevich I, Xue F, Sood AK, et al. Differing clinical impact of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in serous ovarian cancer. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:1523–35. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pothuri B. BRCA1- and BRCA2-related mutations: therapeutic implications in ovarian cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2013;24(Suppl 8):viii22–viii7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicoletto MO, Donach M, De Nicolo A, Artioli G, Banna G, Monfardini S. BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 mutations as prognostic factors in clinical practice and genetic counselling. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2001;27:295–304. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2001.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaye SB, Lubinski J, Matulonis U, Ang JE, Gourley C, Karlan BY, et al. Phase II, open-label, randomized, multicenter study comparing the efficacy and safety of olaparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:372–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.