Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, affecting more than 10% of people over the age of 65. Age is the greatest risk factor for AD, although a combination of genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors also contribute to disease development. Common features of AD are the formation of plaques composed of beta-amyloid peptides (Aβ) and neuronal death in brain regions involved in learning and memory. Although Aβ is neurotoxic, the primary mechanisms by which Aβ affects AD development remain uncertain and controversial. Mouse models overexpressing amyloid precursor protein and Aβ have revealed that Aβ has potent effects on neuroinflammation and cerebral blood flow that contribute to AD progression. Therefore, it is important to consider how endogenous signaling in the brain responds to Aβ and contributes to AD pathology. In recent years, Aβ has been shown to affect ATP release from brain and blood cells and alter the expression of G protein-coupled P2Y receptors that respond to ATP and other nucleotides. Accumulating evidence reveals a prominent role for P2Y receptors in AD pathology, including Aβ production and elimination, neuroinflammation, neuronal function and cerebral blood flow.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, P2Y receptors, neuroinflammation, neurovascular regulation, ATP receptors, purinergic receptors

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive cognitive decline causing the most prevalent form of dementia in western society. The global incidence of AD is estimated to be around 24 million worldwide with a predicted doubling every 20 years until 2040 (Mayeux and Stern, 2012). The neuropathological lesions manifested in AD include senile amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, and are accompanied by reactive microgliosis, dystrophic neurites and loss of neurons and synapses (Serrano-Pozo et al., 2011). The main components of senile plaques are the neurotoxic beta-amyloid peptides (Aβ) that are derived from cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretase (Haass and Selkoe, 2007; Mayeux and Stern, 2012). Conversely, the neurofibrillary tangles are mainly constituted by intracellular accumulation of τ protein (Liu et al., 2005; Selkoe, 2001). Research efforts in the past two decades in animal models of AD have revealed that neuroinflammation plays a crucial role in AD progression. It is well known that Aβ induces microglia to produce nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and IL-18) and prostaglandins (e.g., PGE2), which contribute to neuronal death (Akiyama et al., 2000). Furthermore, studies have also shown that cells involved in the central nervous system (CNS) immune response, such as dendritic cells, microglia, and astrocytes, are able to detect Aβ through Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling. TLR2, in particular, plays a key role in triggering neuroinflammatory events that lead to the activation of signal-dependent transcription factors driving expression of downstream genes associated with the inflammatory pathway (Liu et al., 2005). In addition to a neuroinflammatory phenotype, AD is often preceded by malfunctions in the cerebrovascular system, including accumulation of Aβ in cerebral blood vessels (cerebral amyloid angiopathy) and decreased cerebral blood flow, which leads to hypoxia, breakdown of the blood-brain barrier and ultimately to brain atrophy and death (Bell et al., 2009; Iadecola, 2004; Kelleher and Soiza, 2013; Sagare et al., 2013; Zlokovic, 2008). Studies in mice and humans indicate that Aβ peptides cause forceful constriction of cerebral blood vessels (Niwa et al., 2001; Paris et al., 2003), suggesting that vascular factors play an early pathogenic role in AD.

Purinergic signaling, through activation of A1–3 adenosine receptors, P2X cation channel receptors for ATP and P2Y nucleotide receptors with subtype specificity for ATP, ADP, UTP, UDP and UDP-glucose (Table 1), has been implicated in neuroinflammation, vascular regulation and the progression of many neurodegenerative diseases, including AD (Burnstock, 2008; Burnstock and Ralevic, 2014; Erlinge and Burnstock, 2008; Rahman, 2009; Takenouchi et al., 2010; Weisman et al., 2012a). In the following sections, we discuss experimental evidence linking P2Y receptors to neuroinflammatory events, neuronal functions, the regulation of cerebral blood flow and the pathophysiology of AD.

Table 1.

Known agonists and antagonists of P2YRs

| P2YR subtypes | Endogenous agonists | Synthetic agonists | Synthetic antagonists |

|---|---|---|---|

| P2Y1R | ADP>ATP | 2MeSADP, 2MeSATP, ATPγS, MRS2365 | Suramin, RB2, MRS2179, MRS2279, MRS2365, MRS2500, A3P5PS, PPADS, BzATP |

| P2Y2R | ATP=UTP | ATPγS, UTPγS, BzATP | Suramin, RB2 |

| P2Y4R | UTP (human) ATP (rat, mouse) |

UTPγS | MRS2578, ATP (human), RB2 (rat), PPADS (weak), BzATP (rat) |

| P2Y6R | UDP | UDPγS | Suramin, RB2, PPADS |

| P2Y11R | ATP | BzATP, ADPγS | Suramin, RB2 |

| P2Y12R | ADP | 2MeSADP, ADPγS | Suramin, RB2, ARC69931, ARC66096, MRS2395 |

| P2Y13R | ADP | 2MeSADP, ADPγS | Suramin, RB2, PPADS, ARC69931, ARC66096, MRS2211 |

| P2Y14R | UDP-glucose |

Abbreviations: 2MeSADP, 2-methylthio-adenosine 5′-diphosphate; 2MeSATP, 2-methylthio-adenosine 5′-triphosphate; ATPγS, adenosine 5′-(γ-thio)triphosphate; RB2, reactive blue 2; PPADS, pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid; BzATP, 2′(3′)-O-(4-benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine 5′-triphosphate; UTPγS, uridine 5′-(γ-thio)triphosphate; UDPγS, uridine 5′-(γ-thio)diphosphate

CHANGES IN P2Y RECEPTOR EXPRESSION AND NUCLEOTIDE RELEASE IN AD

P2Y receptor expression in human and animal models of AD

Expression of all eight subtypes of P2YRs (P2Y1,2,4,6,11,12,13,14) has been documented in the brain (Weisman et al., 2012a). In AD patients and mouse models of AD, changes in expression patterns of P2Y1,2,4 receptors have been observed. Immunohistochemical localization of P2Y1R with neurofibrillary tangles, neuritic plaques and neuropil threads, which are associated with AD, has been reported in human AD brain samples (Moore et al., 2000b). Lai et al. assessed the expression of P2Y2,4,6 receptors in human AD brain samples by immunoblot analysis and found lower protein levels of P2Y2R compared to age-matched controls, while P2Y4R and P2Y6R levels were unaltered (Lai et al., 2008). However, lack of specificity for commercially available P2Y2R and P2Y6R antibodies has also been reported (Ben Yebdri et al., 2009; Yu and Hill, 2013). In the TgCRND8 mouse model of AD, which expresses the Swedish (K670N/M671L) and Indiana (V717F) mutations in human APP, P2Y2R mRNA expression is elevated in the brain at 10 weeks of age and reduced after 25 weeks of age compared to age-matched controls (Ajit et al., 2013). In an AD mouse model expressing the Swedish APP mutation and the γ-secretase mutation (PS1dE9), an increase in P2Y4R expression in cerebral cortical sections was observed in activated microglia compared to resting microglia (Li et al., 2013). This study also demonstrated that the microglial P2Y4R contributes to pinocytosis of soluble Aβ, suggesting that the murine P2Y4R is neuroprotective by stimulating microglia-mediated clearance of Aβ (Li et al., 2013).

Effects of Aβ on P2YR expression and nucleotide release

Aβ has been found to alter ATP release and/or P2YR expression in microglia and erythrocytes. In rat primary cortical astrocytes, oligomeric Aβ1–42 (oAβ1–42) induces the release of endogenous ATP (Peterson et al., 2010). In mouse primary microglial cells, fibrillar Aβ (fAβ1–42) and oAβ1–42 aggregates cause ATP release (Kim et al., 2012) and in microglial N13 cells, the Aβ25–35 peptide causes a dose-dependent release of ATP (Sanz et al., 2009). Aβ-induced release of ATP from microglial cells, as well as microglial activation, are dependent on expression of the ionotropic P2X7 receptor, which is thought to release ATP through the formation of a membrane pore (Sanz et al., 2009). Expression of the P2Y2R is upregulated in mouse primary microglia treated with fAβ1–42 or oAβ1–42 aggregates (Kim et al., 2012). In the vasculature, hypoxia causes the release ATP from erythrocytes into the blood stream (Bergfeld and Forrester, 1992) and a 24 h exposure of human erythrocytes to Aβ inhibits ATP release from deoxygenated cells (Misiti et al., 2008). P2Y receptors expressed in human vascular endothelium, including P2Y1,2,4,6R, trigger vasodilation through release of NO, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) and prostacyclin (Burnstock and Ralevic, 2014), thus activation of these receptors may help to counteract the vasoconstrictive effects of Aβ.

ROLE OF P2Y RECEPTORS IN THE REGULATION OF AD SYMPTOMS AND BIOMARKERS

Effects of P2Y receptors on Aβ metabolism

APP production and cleavage

Although it remains unclear whether nucleotides and P2YRs affect the production and/or release of APP in neurons, ATP and UTP have been shown to increase the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-dependent production and secretion of APP in primary rat cortical astrocytes (Tran, 2011), presumably through activation of the P2Y2R and P2Y4R. The non-selective P2YR antagonists, suramin and reactive blue 2 (RB2), inhibited expression of 130 kD APP to similar extents, but suramin was more effective at reducing 110 kD APP expression while RB2 was more effective at inhibiting APP release (Tran, 2011). Considering that suramin is a more potent antagonist of P2Y2R and RB2 is a more potent antagonist of P2Y4R, it was suggested that these two P2YRs may play different roles in the regulation of APP production and release.

Cleavage of APP by β- and γ-secretases produces neurotoxic peptides, Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, whereas cleavage of APP by α- and γ-secretases produces the non-amyloidogenic Aβ17–40/42 fragments (Roberts et al., 1994; Sisodia, 1992; Vassar et al., 2009). Competition between α-secretases (i.e., ADAM9/10/17) and β-secretase (i.e., BACE1) in APP processing has been documented (Deuss et al., 2008; Lichtenthaler, 2012; O’Brien and Wong, 2011; Skovronsky et al., 2000) and production of neurotoxic Aβ is reduced by promoting α-secretase activity (Caccamo et al., 2006; Kuhn et al., 2010). Activation of the P2Y2R enhances α-secretase-mediated APP processing in primary rat cortical neurons and human astrocytoma cells, which was dependent on two members of the ADAM family: ADAM 10 and ADAM17 (Camden et al., 2005; Kong et al., 2009; Leon-Otegui et al., 2011). Regulation of ADAM10/17 activity by the P2Y2R requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and ERK1/2 activity, whereas the involvement of protein kinase C (PKC) varies with cell type (Camden et al., 2005; Kong et al., 2009).

Matrix metalloprotease activity and Aβ degradation

Matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9) is a secreted protease that breaks down extracellular matrix in normal physiological conditions, but is expressed at higher levels in AD patients (Lorenzl et al., 2003) and co-localizes with Aβ plaques (Backstrom et al., 1996). Aβ induces the astrocytic production and activation of MMP-9 (Hernandez-Guillamon et al., 2009; Mizoguchi et al., 2009; Talamagas et al., 2007), which in turn degrades Aβ peptide (Backstrom et al., 1996) and fibrils in vitro (Yan et al., 2006), and compact plaques in situ (Yan et al., 2006). However, homozygous knockout of MMP-9 in mice or administration of GM6001, a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor, was found to improve Aβ-induced memory loss, suggesting that MMP-9 activity promotes Aβ-induced cognitive impairment and neurotoxicity (Mizoguchi et al., 2009). Recently, Kinoshita et al. (2013) reported that MMP-9 production in rat primary astrocytes is increased upon treatment with apyrase, RB2 and pertussis toxin (PTX, a Gi-inhibitor). By pharmacological examination with P2Y agonists and antagonists, P2Y14R was identified to be associated with MMP-9 production and knockdown of P2Y14R led to a significant increase in MMP-9 expression. Treatment of astrocytes with apyrase, RB2 or PTX, also increased expression of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-3, TNF-α, tissue inhibitory metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1 and monocyte chemoattrant protein-1 (MCP-1). While TIMP-1 is known to bind MMP-9 and inhibit its proteolytic activity (Hernandez-Guillamon et al., 2009), TNF-α induces MMP-9 release from astrocytes in vitro (Kinoshita et al., 2013). These findings suggest a protective role of the P2Y14R in AD via suppressing MMP-9 expression.

Effects of P2Y receptors on neuroinflammation

There is now a consensus that neuroinflammation is involved in AD, although its role remains ambiguous, whether as a primary cause of disease progression or a protective response (Rivest, 2009; Wyss-Coray and Rogers, 2012). While clinical trials of anti-inflammatory drugs are still inconclusive for AD treatment (Wyss-Coray and Rogers, 2012), modulation of inflammation has been effective in animal models of AD (Klegeris et al., 2007; McGeer et al., 2005; Rozemuller et al., 2005).

Cytokine and chemokine production

In monocytes and microglia, Aβ induces secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, as well as chemokines, including CC chemokines CCL2/macrophage inflammatory protein-1α/β (MIP-1α/β), MCP-1 and CXC chemokine IL-8 (Akiyama et al., 2000; Fiala et al., 1998; Walker et al., 1995). Among these cytokines, IL-1β is particularly important for regulating the expression of other proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, and interferons) and chemokines (e.g., CXCL1 and CXCL2) (Rothwell and Luheshi, 2000; Shaftel et al., 2008). In vivo, over-expression of IL-1β in the hippocampus accelerates phagocyte recruitment and clearance of Aβ plaques in a mouse model of AD (Shaftel et al., 2007). In vitro, Aβ causes IL-1β release from microglia that is dependent on P2X7R expression (Sanz et al., 2009). Aβ treatment also increases expression of the P2Y2R in microglia (Kim et al., 2012) and neurons (Kong et al., 2009; Peterson et al., 2013), which is likely triggered by P2X7R-mediated IL-1β release (Chakfe et al., 2002; Choi et al., 2007; D’Alimonte et al., 2007; Mingam et al., 2008; Sanz et al., 2009; Suzuki et al., 2004; Takenouchi et al., 2011; Takenouchi et al., 2009).

P2Y1 receptors are important for regulating cytokine and chemokine production in a rat cerebral stroke model and, therefore, may also affect neuroinflammatory conditions occurring in AD. In the cerebral stroke model, administration of the P2Y1R specific agonist MRS2365 significantly increased the infarct volume (a measure of cerebral damage) after a 30-min occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (MCAO), whereas administration of the P2Y1R antagonists MRS2179, A3P5PS and MRS2279 significantly reduced infarct volume (Kuboyama et al., 2011). Furthermore, upregulation of cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, CCL2/MCP-1 and interferon-inducible protein-10 (IP-10)/CXCL10, was inhibited after MCAO by MRS2179 application. The P2Y1R-dependent upregulation of cytokines and chemokines and cerebral infarct were suggested to act via the NF-κB signaling pathway (Kuboyama et al., 2011). Similarly, Chin et al. (2013) observed hippocampal neuroinflammation and microstructural alterations, as well as a long-lasting deficit in cognitive function, after a 90-min MCAO in wild-type rats and mice. However, MCAO in P2Y1R−/− mice caused defective sensory-motor function but cognition and hippocampal neuroinflammation and microstructure were unaltered. In addition, treatment with the P2Y1R-specific antagonist MRS2500 helped wild-type mice maintain cognitive function after MCAO (Chin et al., 2013).

Microglia recruitment

Microglial cells are CNS macrophages that differentiate from monocytes. As the primary immune effector cells in the CNS, activated microglia are thought to play a neuroprotective role in AD by migrating towards Aβ plaques (Bolmont et al., 2008; Frautschy et al., 1998; Meyer-Luehmann et al., 2008; Perlmutter et al., 1990; Zheng et al., 2010) and clearing neurotoxic Aβ by endocytosis (Bolmont et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2012; Shie et al., 2005) and degradation (Jiang et al., 2008). The importance of microglia in reducing Aβ levels has been confirmed not only in AD mouse models, but also in Aβ-immunized AD patients who showed decreased plaque load and increased microglial cell accumulation (Boche et al., 2010; Nicoll et al., 2003; Schenk et al., 1999). The population of microglia in the CNS can be amplified by recruiting blood-derived macrophages/monocytes (Hao et al., 2011; Simard et al., 2006). In an in vitro blood-brain barrier model, monocytes pretreated with Aβ1–42 on the “brain side” were recruited much more effectively from the “blood side” than untreated monocytes, a process thought to be related to Aβ1–42-induced secretion of chemokines (Fiala et al., 1998).

In an early in vitro study, extracellular ATP or ADP enhanced membrane ruffling and migration of cultured microglia (Honda et al., 2001). Later, local ATP was found to cause a rapid chemotactic response in microglia to local brain injury and ATP induced further release of ATP from surrounding astrocytes that was essential to the microglial response (Davalos et al., 2005). Although the P2 receptor subtype responsible for microglial migration to the injured site was not determined, application of the ATP-hydrolyzing enzyme apyrase or the P2YR inhibitors, RB2 and PPADS, showed efficient inhibition, whereas inhibition by suramin was incomplete (Davalos et al., 2005). ADP-induced membrane ruffling and chemokinesis of microglia is inhibited by the P2Y12/13R antagonist ARC69931 or by elevated intracellular cAMP levels, indicating P2Y12/13R-mediated microglia chemokinesis towards ADP (Nasu-Tada et al., 2005). Moreover, the β1 integrin is thought to be involved since it traffics to membrane ruffles after ADP stimulation (Nasu-Tada et al., 2005).

The importance of the P2Y12R in microglia polarization, migration and extension of processes toward nucleotides in vitro and in vivo was later supported by Haynes et al. (2006). They showed primary brain microglia from wild-type, but not the P2Y12R−/− mice, underwent membrane ruffling after exposure to ATP, ADP, or 2MeSADP. In living brains of P2Y12R−/− mice, the microglial processes extending toward the exogenous ATP resource or sites of focal laser ablation were significantly reduced in comparison to those in wild-type mice (Haynes et al., 2006). Impairment of microglial chemotaxis to ATPγS (an ATP homologue) in rat primary microglia after treatment with MRS2395, a selective antagonist of the P2Y12R, has also been reported (Li et al., 2013). These observations are consistent with an earlier report that P2Y12R-expressing microglia accumulate around damaged neurons in vivo (Sasaki et al., 2003). Interestingly, it was found that “resting” (albeit quite dynamic) microglia express more P2Y12R than activated microglia (Haynes et al., 2006), whereas the immunoreactivity of P2Y12R was not observed in macrophages in spleen or abdominal cavity (Haynes et al., 2006; Sasaki et al., 2003). Hence, the function of the P2Y12R might be to selectively motivate resting microglia for chemotaxis in the CNS.

Although microglial P2Y1R is undetectable, cytokines and chemokines released by P2Y1R-expressing astrocytes lead to macrophage infiltration and microglia activation in ischemic rat brain, which are abrogated by the P2Y1R antagonist MRS2179 (Kuboyama et al., 2011). The importance of P2Y1R in astrocytes challenged with extracellular ATP has also been implied by its involvement in ATP-induced ERK activation in response to stretch-induced injury (Neary et al., 2003).

P2Y6R was at first thought to mediate only the phagocytosis but not the chemotaxis or migration of microglia (Koizumi et al., 2007). However, Kim et al. (2011) found in primary cultured microglia, astrocytes and cortical slice cultures that UDP, a selective agonist of P2Y6R, induces expression of the chemokines CCL2 (MCP-1) and CCL3 (MIP-1α), which are important for monocyte infiltration into the injured brain. Two calcium-activated transcription factors, NFATc1 and c2, rather than NF-κB, were responsible for UDP-induced chemokine expression. Moreover, UDP-treated astrocytes recruited monocytes in an in vitro transmigration assay (Kim et al., 2011). Based on their regulation of microglia migration, P2Y1,6,12,13Rs in microglia may contribute to the pathophysiology of AD, although direct evidence is still lacking.

More evidence exists for the essential role of the P2Y2R in recruiting microglia to the brain during the development of AD. Although UTP was reported to be insufficient to induce ruffle formation in rat primary microglia (Haynes et al., 2006; Honda et al., 2001), it enhances migration of mouse primary microglia in vitro (Kim et al., 2012). In the TgCRND8 mouse model of AD, expression of CD11b, a marker for activated microglia, is elevated in hippocampal brain sections but reduced when P2Y2R expression is suppressed (Ajit et al., 2013).

Aβ uptake and degradation by microglia

Phagocytes, including microglia, use two types of clathrin-independent endocytosis: pinocytosis for uptake of liquids and phagocytosis for uptake of solids. Pinocytosis is further divided into two separate pathways: micropinocytosis and macropinocytosis, whose vesicle diameters and mechanisms differ. It has been experimentally demonstrated that microglia-mediated clearance of soluble Aβ is via macropinocytosis, both in vitro and in vivo (Mandrekar et al., 2009). The clearance of insoluble fAβ and fAβ-containing plaques is carried out by microglial phagocytosis, during which fAβ interacts with a cell surface receptor complex formed by the B-class scavenger receptor CD36, the α6β1 integrin and CD47/integrin associated protein (Bamberger et al., 2003; Koenigsknecht and Landreth, 2004).

The UDP-activated P2Y6R was found to stimulate phagocytosis in rat primary microglia where a CysLT receptor was involved (Koizumi et al., 2007). This P2Y6R-mediated microglial phagocytosis was confirmed by an in vivo phagocytosis assay in which fluorescently-labeled microspheres were injected into rats receiving kainic acid (KA), a brain injury model (Koizumi et al., 2007). Recently, time-lapse imaging visualized P2Y6R-mediated microglial cell membrane motility. Application of 100 μM UDP stimulated both immediate formation of lamellipodia-like structures and long-lasting active motility in the cell membranes (Uesugi et al., 2012). Moreover, UDP treatment induced formation of large vacuoles that had taken up extracellular fluorescently-labeled dextran, soluble Aβ1–42 or microspheres, which demonstrated that the P2Y6R mediates macropinocytosis and phagocytosis. These endocytic processes involved PKC-independent functions and protein kinase D (Uesugi et al., 2012).

In monocytes and macrophages, the P2Y2R is a critical sensor of nucleotides released by apoptotic cells, whose phagocytic clearance function is promoted (Elliott et al., 2009). Consistent with this, the phagocytosis and degradation of insoluble fAβ1–42 and oAβ1–42 aggregates by primary microglia was enhanced after UTP stimulation that activated the P2Y2R, as well as the αv integrin, Rac and Src pathways, neuroprotective responses (Kim et al., 2012). There is a similarity between the tyrosine kinase-Vav-Rac1 signaling cascade following fAβ-CD36 binding in microglia (Wilkinson et al., 2006) and the Vav2-Rac1 signaling cascade activated by association of the P2Y2R and αv integrin (Bagchi et al., 2005). Therefore, it was hypothesized that the P2Y2R and CD36 both interact with CD47 and its associated integrins to induce phagocytosis of insoluble Aβ by microglia (Kim et al., 2012).

Li et al. (2013) found that application of UTP, ATP or ATPγS, a non-hydrolyzable ATP homologue, efficiently stimulated pinocytosis in primary rat microglia. At first, both rat P2Y4R and P2Y2R were suspected to be involved, since unlike humans where ATP is an antagonist of the P2Y4R, in rats ATP is an agonist of P2Y4R with less potency than UTP (Kennedy et al., 2000). Using specific siRNAs, it was determined that the P2Y4R was responsible for pinocytosis. Such P2Y4R-mediated pinocytosis occurs spontaneously without exogenous nucleotide stimulation to internalize soluble Aβ1–42, but not an Aβ42-1 control (Li et al., 2013). In regards to the pharmacological differences between murine and human P2Y4Rs, it will be important to assess whether human P2Y4Rs mediate microglial pinocytosis of soluble Aβ.

Oxidative stress

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), mainly superoxide (O2−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), are unavoidable by-products of cellular respiration. ROS react with molecules within cells, including DNA, and cause cell damage, i.e., oxidative stress. One of the major contributors of oxidative stress is the NADPH oxidase (NOX) complex that produces O2−.

Oxidative stress is a noted contributor to the pathogenesis of AD and has been recently reviewed (Mao and Reddy, 2011). Antioxidants and NOX-targeting therapeutics have shown positive effects in counteracting oxidative stress in vitro and in rodent models of AD (Simonyi et al., 2010). Primary cortical neurons exposed to Aβ1–42 had significant ROS production, which required NOX activity (Shelat et al., 2008). Primary hippocampal neurons treated with the general NOX inhibitor apocynin and soluble oAβ1–42, survived better than neurons treated with oAβ1–42 alone (Bruce-Keller et al., 2010). AD patients with mild cognitive impairment followed longitudinally had higher NOX expression and activity in the temporal gyri than controls, whereas preclinical or late-stage AD samples showed no difference (Bruce-Keller et al., 2010). Hence, the NOX-mediated redox pathway may be a pathogenic mechanism mainly in early AD within vulnerable regions of the brain, which may relate to previous clinical trials with antioxidants that failed to significantly retard AD progression (Pratico, 2008).

Microglia are known to express the NOX1, NOX2 and NOX4 subtypes, and treatment of mouse microglial BV2 cells with the P2Y2/4R specific agonist UTPγS increases expression of NOX1 and NOX2, but not NOX4 (Mead et al., 2012). UTPγS also increased O2− production, whereas the P2Y1R agonist MRS2365 had no effect. Interestingly, the UTPγS-induced production of O2− was inhibited by apocynin, but not by thioridazine (an inhibitor of the ferrocytochrome subunit of NOX) or wortmanin (an inhibitor of PI3K-mediated NOX2 regulation), whereas rottlerin (an inhibitor of PKC-mediated NOX1 regulation) slightly enhanced UTPγS-induced O2− production. Apocynin-sensitive O2− production in primary rat microglia was induced by BzATP (Mead et al., 2012), a stable ATP homologue and a potent agonist of the P2X7R, but also an agonist for the rat P2Y2R (Wildman et al., 2003).

To protect cells from oxidative stress, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and biliverdin reductase-A can be induced to neutralize ROS. In the hippocampus of samples from postmortem AD patients, HO-1 protein levels and serine phosphorylation are significantly higher than in the age-matched controls (Barone et al., 2012). Potential roles for nucleotides and P2YRs in protection from oxidative stress in AD were suggested by Espada et al. (2010), who found that HO-1 was upregulated in primary cerebellar granule neurons (CGN) from rats and mice after treatment with ADP or its stable analogue 2MeSADP. Among the three 2MeSADP-reactive P2YR subtypes, P2Y12R was barely expressed in CGN and it was determined that the P2Y13R and not the P2Y1R mediates ADP/2MeSADP-induced HO-1 expression, using the selective antagonists of P2Y13R and P2Y1R, MRS2179 and MRS2211, respectively. It also was shown that activation of the transcription factor Nrf2 is critical to 2MeSADP-evoked protection of CGN from H2O2-induced death (Espada et al., 2010). In contrast, Fujita et al. (2009) found that ATP and 2MeSADP had no impact on the cell death of primary rat hippocampal neurons exposed to H2O2. However, when these neurons were co-cultured with primary astrocytes, the H2O2-induced neuronal death was greatly decreased after ATP or 2MeSADP pretreatment. Using P2Y1R-specific siRNA, it was shown that this neuroprotection against oxidative stress was conferred by activation of astrocytic P2Y1R and release of IL-6 in response to extracellular ATP (Fujita et al., 2009).

Effects of P2Y receptors on neuronal function

P2Y receptors in neurons have been shown to mediate neuroprotective responses through their regulation of axonal growth, neurite extension and synaptic transmission. All of the P2Y receptor subtypes are expressed in neurons or oligodendrocytes under a variety of conditions (Amadio et al., 2007; del Puerto et al., 2012; Heine et al., 2007; Koles et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2000a; Weisman et al., 2012b). Although relatively few studies have examined the roles of these P2Y receptors in the context of AD, studies have determined functional responses in neurons mediated by each P2Y receptor subtype that are thought to be protective in the face of inflammation or other pathological insults in the brain. In addition, a wide range of agonists and antagonists that are relatively selective for specific P2Y receptor subtypes have been developed (Weisman et al., 2012b) that may ultimately prove useful in the treatment of AD and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Expression of P2Y receptors in neurons

The P2Y1R for ADP is widely expressed in the brains of mammals, including in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Koles et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2000a; Moran-Jimenez and Matute, 2000; Simon et al., 1997), regions predominantly impacted in AD (Lee et al., 2010; Obulesu et al., 2011; Wyss-Coray and Rogers, 2012; Zilka et al., 2006). The P2Y1R has been shown to be expressed in glutamatergic and glycinergic neurons (Jimenez et al., 2011; Rodrigues et al., 2005), oligodendrocytes (Agresti et al., 2005), neuroprogenitor cells (Mishra et al., 2006), dorsal root ganglia and horn neurons (Kobayashi et al., 2006; Ruan and Burnstock, 2003; Sanada et al., 2002). In human brain from AD patients, P2Y1Rs in neurons co-localize with tau tangles and Aβ plaques (Moore et al., 2000b).

Low expression levels of the P2Y2R for ATP and UTP have been demonstrated in neurons of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Moore et al., 2001; Verkhratsky et al., 2009). However, P2Y2R expression has been shown to be significantly increased in cortical neurons upon treatment with the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β, whose levels are elevated in AD patients and animal models of AD, as compared to normal controls (Cacabelos et al., 1994; Lee et al., 2010). Interestingly, the P2Y2R is also upregulated in mammalian cells and tissues under conditions associated with inflammation or injury (Kong et al., 2009; Koshiba et al., 1997; Schrader et al., 2005; Seye et al., 2002; Shen et al., 2004; Turner et al., 1997), including in the spinal cord (Rodriguez-Zayas et al., 2010) and brain (Franke et al., 2004). These findings suggest that P2Y2R upregulation in neurons in response to cell damage plays a potential role in neuroprotection.

Recent studies have shown that P2Y4R and P2Y6R can function as homo- or heterodimers in neurons (D’Ambrosi et al., 2007). Both P2Y4R and P2Y6R mRNA are detected in rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Rodrigues et al., 2005), whereas P2Y6R mRNA is expressed in mouse superior cervical ganglion (Calvert et al., 2004) and rat dorsal-root ganglion neurons (Ruan and Burnstock, 2003; Sanada et al., 2002). The P2Y4 and P2Y6 receptors (D’Ambrosi et al., 2007; Koles et al., 2011) are expressed in other neuronal cell types of the CNS (Moore et al., 2001; Verkhratsky et al., 2009).

Expression of the P2Y11R for ATP has been described in rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons, cerebellar Purkinje cells (Rodrigues et al., 2005; Volonte et al., 2006) and other neuronal cell types (Moore et al., 2001; Verkhratsky et al., 2009). P2Y11R activation has been shown to inhibit apoptosis induced by pathogens or inflammation, suggesting a role in neuroprotection (Vaughan et al., 2007). Other studies have shown that the P2Y12R, known to regulate platelet aggregation (Dorsam and Kunapuli, 2004; Jantzen et al., 1999; Wallentin, 2009; Xu et al., 2002), is expressed in neurons (Jimenez et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2001; Rodrigues et al., 2005; Verkhratsky et al., 2009) and oligodendrocytes (Amadio et al., 2006).

P2Y13Rs for ADP are expressed in a variety of neuronal cell types (Jimenez et al., 2011; Moore et al., 2001; Verkhratsky et al., 2009), where they have been postulated to play a role in cell survival (Weisman et al., 2012b). P2Y14Rs for UDP-glucose have been detected in neurons (Moore et al., 2001; Verkhratsky et al., 2009), and sensory neurons have been shown to express P2Y13 and P2Y14, as well as P2Y1 receptors (Malin and Molliver, 2010).

Neuroprotective responses mediated by P2Y receptors

Cellular functions coupled to the activation of various P2YR subtypes in neurons appear to be largely neuroprotective, suggesting that these receptors could serve as effective pharmacological targets to impede the progression of AD. However, these pathways have not been investigated as extensively as the neuroprotective functions of P2YRs in glial cells of the brain (see above). Nonetheless, the activation of specific P2YR subtypes in neurons has been shown to stimulate neurite extension/axonal elongation and non-amyloidogenic processing of APP and promote cell survival, as described below.

The coordinate regulation of axonal growth by the P2Y1 and P2Y13 receptors has been demonstrated in rat hippocampal neurons, where axonal elongation is stimulated by the P2Y1R through Gq-dependent activation of PI3K and axonal elongation is inhibited by the P2Y13R via Gi-dependent activation of adenylate cyclase, pathways that could be targeted to counteract the neurodegenerative effects of neurofibrillary tangles (del Puerto et al., 2012). Studies with rat primary cortical neurons indicate that neurite extension is stimulated by P2Y2R-mediated interactions with αvβ3/5 integrin leading to activation of a pathway involving G12-dependent Rho activation and the phosphorylation of the actin-depolymerizing protein cofilin (Peterson et al., 2013), which is known to promote neurite extension (Aizawa et al., 2001; Endo et al., 2007; Endo et al., 2003; Figge et al., 2012; Meberg and Bamburg, 2000; Meberg et al., 1998). Activation of the P2Y2R in the presence of nerve growth factor has been shown to enhance tyrosine kinase A-dependent neuronal differentiation and acceleration of neurite formation in PC12 cells and dorsal root ganglion neurons (Arthur et al., 2005). Therefore, the ability of P2Y2Rs to be upregulated by the cytokine IL-1β, whose levels are elevated in the AD brain, strongly suggests that acute inflammation serves to stimulate P2Y2R-mediated neuroprotection (i.e., enhanced axonal elongation/neurite outgrowth) in response to extracellular nucleotide release from activated glia or apoptotic cells in the inflammatory environment of early AD.

Activation of the P2Y2R in primary cortical neurons and neuroblastoma cells increases the α-secretase-dependent degradation of APP to generate the soluble APPα peptide rather than neurotoxic Aβ1–42 peptide, a response that can be prevented by pretreatment with inhibitors of the metalloproteases ADAM10/17, i.e., the TNF-α converting enzyme (Camden et al., 2005; Kong et al., 2009). It has been shown that neuropathology in AD (e.g., synapse loss) is correlated with a decrease in P2Y2R expression in the parietal cortex of human postmortem AD brain samples (Lai et al., 2008), as compared to controls, which is similar to the enhanced neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative phenotype seen in the TgCRND8 mouse model of AD upon knockout of the P2Y2R (see below). The P2Y2R also protects against trauma-induced death of astrocytic cells (Burgos et al., 2007), through P2Y2R-mediated phosphorylation of the pro-apoptotic factor Bad and reduction in the bax/bcl-2 mRNA expression ratio (Chorna et al., 2004), which are known to be involved in cell survival mechanisms. Thus, loss of protective functions regulated by the P2Y2R in brain neurons and glial cells in humans and mice appears to promote the progression of the AD phenotype and suggests that activation of P2Y2Rs may serve to delay neurodegeneration caused by inflammation in the AD brain.

Other potential neuroprotective responses mediated by P2YR activation in neurons include the enhancement of Na+- and Cl−-dependent glycine transport in the synaptic cleft by P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptor activation (Jimenez et al., 2011) and resensitization of ionotropic P2X2 receptors (Chen et al., 2010) and vanilloid type 1 channels (TRPV1) in sensory neurons by P2Y2R activation (Wang et al., 2010). P2Y11R activation in glutamatergic neurons also can delay cell apoptosis by a cAMP-dependent mechanism (Vaughan et al., 2007), whereas P2Y13R activation inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 phosphorylation and enhances the PI3K/Akt-dependent nuclear translocation of β-catenin leading to the elevated expression of cell survival genes (Ortega et al., 2008). Activation of the P2Y13R also has been shown to induce the expression of Nrf2 and cytoprotective heme oxygenase-1 to prevent oxidative stress-induced death in neurons (Espada et al., 2010). As recently reviewed (Koles et al., 2011), activation of P2YRs can increase dopamine (Heine et al., 2007; Krugel et al., 1999; Krugel et al., 2001) and glutamate release (Price et al., 2003), but also can inhibit neurotransmitter release (De Lorenzo et al., 2006) in the cerebral cortex(Bennett and Boarder, 2000; Cunha et al., 1994; Luthardt et al., 2003; Rodrigues et al., 2005; von Kugelgen et al., 1994) and hippocampus (Csolle et al., 2008; Koch et al., 1997; Mendoza-Fernandez et al., 2000). This wide diversity in the regulatory effects on neurotransmission caused by activation of individual P2Y receptor subtypes requires further investigation, particularly in the context of neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD.

Although P2YRs, including the P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors, are expressed in oligodendrocytes (Agresti et al., 2005; Amadio et al., 2006), little is known about the functional role of these P2Y receptors in this important neuroprotective cell type that regulates axonal myelination and other functions (Liu et al., 2013). Since the AD phenotype has been associated with oligodendrocyte dysfunction (Higuchi et al., 2005; Kohama et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013; Rowe et al., 2007), the investigation of P2YR functions in these cells may elucidate novel pharmacological targets to enhance neuroregenerative pathways mediated by oligodendrocytes. P2Y12R expression in oligodendrocytes has been found to decrease with demyelination in cortical grey matter lesions of post-mortem multiple sclerosis brain samples (Amadio et al., 2010) and decreases in P2Y2R expression have been reported in human AD brain (Lai et al., 2008). Thus, the loss of P2YR receptor functions appears to correlate with neuronal dysfunction associated with neurodegenerative diseases and more studies are needed to determine whether approaches that promote upregulation and sustained activation of specific P2YR subtypes in neurons will lead to a slower onset of neurological deficits in AD.

Neurovascular dysregulation in AD

Evidence over the last decade suggests that vascular dysfunction in the brain plays a central role in the development of AD and is the subject of several reviews (Bell and Zlokovic, 2009; Iadecola, 2004; Kelleher and Soiza, 2013; Sagare et al., 2013; Zlokovic, 2008). Breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is observed more frequently in AD patients than age-matched controls without AD (Claudio, 1996; Matsumoto et al., 2007) and brain-imaging techniques have revealed that there is typically a reduction in cerebral blood flow (CBF) during the development of AD (Alsop et al., 2000; Ruitenberg et al., 2005; Schuff et al., 2009; Warkentin et al., 2004). In transgenic mice overexpressing the Swedish mutation of APP, behavioral deficits and memory loss occur at 6 months of age and amyloid plaques at 9–12 months (Hsiao et al., 1996; Kawarabayashi et al., 2001; Westerman et al., 2002). However, reductions in CBF precede these events and are observed as early as 2 months of age and include disruption of cerebrovascular autoregulation and attenuation of increases in CBF caused by endothelium-dependent vasodilators (Niwa et al., 2002; Niwa et al., 2000b). These cerebrovascular effects are greater in transgenic mice that express higher brain levels of Aβ and occur in the absence of cognitive impairment or amyloid plaques (Niwa et al., 2002; Niwa et al., 2000b). Furthermore, cerebrovascular dysregulation can be reproduced in normal mice by topical application of Aβ1–40 to the neocortex (Niwa et al., 2000a). In isolated cerebral arteries from rodents and humans, Aβ causes blood vessel constriction that can be reversed by treatment with free radical scavengers, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD1) (Niwa et al., 2001; Paris et al., 2003). SOD1 treatment also reverses cerebrovascular dysfunction in mice overexpressing mutant APP (Iadecola et al., 1999), suggesting that Aβ causes vasoconstriction through production of free radicals. These observations support the hypothesis that soluble Aβ is a crucial factor in cerebrovascular dysfunction in AD that occurs early in disease progression, well before deposition of Aβ in amyloid plaques.

Hypoxia is a direct consequence of reduced CBF and is a common component of many AD risk factors, including stroke, atherosclerosis, hypertension and diabetes mellitus. In vivo studies show that exposure of mice overexpressing mutant APP to hypoxia greatly accelerates the appearance of AD symptoms and biomarkers, including memory loss and increased β-amyloid plaque deposition and brain levels of Aβ and BACE1, the secretase that is critical for the generation of Aβ (Sun et al., 2006). Furthermore, in vitro experiments show that hypoxia increases the level of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and BACE1 in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells and that the BACE1 promoter contains a hypoxia response element that binds and is activated by HIF-1α (Sun et al., 2006). Therefore, it is thought that reduced CBF and the resulting hypoxia facilitates AD pathogenesis by increasing the production of HIF-1α and HIF-1α-inducible proteins, including BACE1 (Zhang et al., 2007), VEGF (a vascular endothelial growth factor that increases vascular permeability and breakdown of the BBB) (Yeh et al., 2007), endothelin-1 (a potent vasoconstrictor) (Hisada et al., 2012), RAGE (a receptor for advanced glycation end products that transports Aβ from the bloodstream to underlying tissues) (Pichiule et al., 2007), serum response factor and myocardin (transcription factors that suppress expression of LRP1, a major transporter of Aβ from vascular cells in the brain to the bloodstream) (Bell et al., 2009; Chow et al., 2007) and PERK (an endoplasmic reticulum kinase that deactivates translation initiation factor eIF2α and represses global protein synthesis that is necessary for synaptic plasticity and memory function) (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2013).

Cerebrovascular effects of nucleotides and P2Y receptors

Purinergic signaling regulates vascular blood flow throughout the body and brain and has been extensively reviewed (Burnstock and Ralevic, 2014; Erlinge and Burnstock, 2008). Long ago, ATP release from active brain slices was detected (Pull and McIlwain, 1972) and shown to stimulate oxygen uptake and increase CBF (Forrester, 1978). In general, regulation of cerebrovascular tone by nucleotides (i.e., vasoconstriction versus vasodilation) depends on the nucleotide source. When ATP is released as a neurotransmitter or cotransmitter with noradrenaline from perivascular sympathetic nerves it causes vasoconstriction by activating P2X1 and P2Y2,4,6 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells (Burnstock and Knight, 2004; Burnstock and Ralevic, 2014). When ATP and UTP are released into the vascular lumen (e.g., from endothelial cells in response to changes in blood flow induced by exercise (Farias et al., 2005; Hashimoto et al., 1999) or hypoxia (Bodin and Burnstock, 1995), from erythrocytes in response to hypoxia (Bergfeld and Forrester, 1992) or from activated platelets and immune cells (Beigi et al., 1999; Eltzschig et al., 2006; Piccini et al., 2008)) they cause vasodilation by activating P2Y1,2,4,6 receptors on endothelial cells (Burnstock and Ralevic, 2014). Studies in various vasculature systems, including the cerebral vasculature, have shown that intraluminal application of ATP or UTP (equipotent agonists of the P2Y2R) induces endothelium-dependent dilation of blood vessels and a decrease in blood pressure, which have been attributed to activation of the endothelial P2Y2R (Dietrich et al., 2009; Guns et al., 2006; Kennedy and Burnstock, 1985; Miyagi et al., 1996; Ralevic and Burnstock, 1996; Rieg et al., 2007; Rieg et al., 2011; Terada et al., 1976). P2Y1,2,4,6 receptors, which are expressed in human and rodent vascular endothelium (Guns et al., 2005; Wihlborg et al., 2003), increase blood flow through the release of NO, prostaglandins and EDHF (Buvinic et al., 2002; Guns et al., 2006; Lustig et al., 1992; Wihlborg et al., 2003).

The effects of nucleotides on cerebrovascular tone vary, however, depending on the species, size and age of blood vessel being studied. For example, in isolated human pial arteries, 10−7 to 10−5 M UTP and UDP cause transient, endothelium-dependent dilation and endothelium-independent constriction at higher concentrations (Hardebo et al., 1987), suggesting that P2Y2,4,6 receptors are involved. In human cerebral arteries denuded of endothelium, activation of the P2Y6 receptor causes vasoconstriction (Malmsjo et al., 2003). ATP- and ADP-induced dilation of arteries isolated from monkeys was endothelium-dependent in temporal arteries, but largely endothelium-independent in cerebral arteries (Toda et al., 1991). In baboon and cat cerebral arterioles, perivascular and intracarotid application of ATP increases CBF at concentrations ranging from 10−11 to 4×10−8 M (Forrester et al., 1979). In bovine middle cerebral arterial strips, UTP causes constriction when the endothelium is removed, but causes dilation via NO when the endothelium is present (Miyagi et al., 1996). ADP-induced dilation of rabbit small cerebral arteries was endothelium-dependent (Brayden, 1991). In isolated rat cerebral arterioles, microapplication of ATP causes transient constriction via smooth muscle P2X1 receptors and sustained dilation that is primarily due to endothelial P2Y receptor activation (Dietrich et al., 2009). In aging rat cerebral arteries, downregulation of P2X1 and upregulation of P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptor mRNA levels are observed in smooth muscle cells, whereas downregulation of P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptor mRNA levels are observed in endothelial cells (Miao et al., 2001), suggesting that age affects cerebrovascular responses to nucleotides. Although cerebral capillary studies are not available, capillary blood flow in the subventricular region of the mouse brain in response to UTP has been investigated. Using laser Doppler flowmetry, Lacar et al. (2012) showed that intraventricular UTP injection transiently decreases blood flow. Furthermore, they demonstrate that UTP application to acute brain slices increases calcium levels in pericytes leading to capillary constriction (Lacar et al., 2012).

A recent ex vivo study by Dietrich et al. (2010) in rat penetrating cerebral arterioles, the vessels most responsible for controlling cerebrovascular resistance, looked at the vasoconstrictive/vasodilatory effects of extraluminally applied ATP and soluble Aβ. They found that extraluminal application of ATP causes transient vasoconstriction and sustained vasodilation. Furthermore, they demonstrate that extraluminal application of Aβ causes significant vasoconstriction through a ROS-dependent mechanism and that co-application of ATP and Aβ enhances the transient ATP-induced vasoconstriction and diminishes the sustained ATP-induced vasodilation (Dietrich et al., 2010). This suggests that endothelial P2YRs play an important role in counteracting cerebral vasoconstriction and reduced CBF caused by Aβ as it begins to accumulate during the early stages of AD.

In vivo effects of the loss of P2Y2 receptor expression in an AD mouse model

Previous studies with post-mortem human AD brain tissue show decreased expression of P2Y2Rs, as compared to non-AD controls (Lai et al., 2008). Interestingly, recent studies show initial upregulation of the P2Y2R during early stage disease pathology (10–25 weeks) in TgCRND8 mice, a well-characterized AD mouse model. However, the expression of P2Y2R decreases by 25–48 weeks of age with disease progression (Ajit et al., 2013), suggesting that P2Y2R-mediated neuroprotection is available early in AD, but is lost at later stages of the disease.

Mortality

The heterozygous deletion of the P2Y2R in the TgCRND8 mouse model of AD leads to accelerated pathology and premature death (10–12 weeks) compared to TgCRND8 mice expressing the full complement of P2Y2R. Furthermore, homozygous deletion of the P2Y2R in TgCRND8 mice leads to a sharp decline in the survival rate with death occurring at 4–5 weeks of age (Ajit et al., 2013). Other studies indicate that the cellular distribution of the P2Y1R is altered in human AD brains, where the P2Y1R is localized to neurofibrillary tangles, neuropil threads and neuritic plaques (Moore et al., 2000b). However, the functional consequences of P2Y1R redistribution in AD require further investigation. Nonetheless, these observations indicate a potential beneficial role for P2YRs in the prevention of AD.

Aβ accumulation

Chronic inflammation contributes to neurodegeneration in AD (Akiyama et al., 2000; Griffin, 2006; Ho et al., 2005), however, acute inflammation is important for tissue repair and may limit brain damage (Monsonego and Weiner, 2003), in part by promoting the clearance of Aβ. Accumulation of Aβ is a characteristic feature of AD and current therapeutic strategies are targeting mechanisms that enhance the clearance of Aβ. Previous studies have shown that P2Y2R upregulation and activation enhances fibrillar Aβ1–42 uptake by microglial cells through P2Y2R interaction with αv integrins that results in activation of Rac1, a signaling protein known to regulate phagocytosis (Kim et al., 2012). These results were substantiated by heterozygous deletion of the P2Y2R in TgCRND8 mice, which accelerates accumulation of soluble Aβ in the brain as compared to age-matched TgCRND8 mice with a full complement of P2Y2R. These studies support a role for the P2Y2R in the phagocytosis and degradation of Aβ in the brain, particularly since heterozygous deletion of the P2Y2R in TgCRND8 mice did not alter levels of APP or the APP processing enzymes ADAM10, ADAM17 or BACE1. Therefore, it seems likely that increased Aβ accumulation upon P2Y2R deletion is related to the inefficient clearance of Aβ.

Microglial cell recruitment

Under neuroinflammatory conditions associated with AD, resident microglia become activated, proliferate and migrate towards and surround Aβ plaques (Bolmont et al., 2008), and blood-derived macrophages infiltrate the brain (Hao et al., 2011; Simard et al., 2006). These activated microglia are thought to play a neuroprotective role through the phagocytosis and degradation of neurotoxic forms of Aβ (Jiang et al., 2008). The crucial role of microglia in controlling Aβ levels has been demonstrated in AD mouse models and AD patients where Aβ immunization has been shown to decrease plaque load and increase microglial cell accumulation (Boche et al., 2010; Nicoll et al., 2003; Schenk et al., 1999).

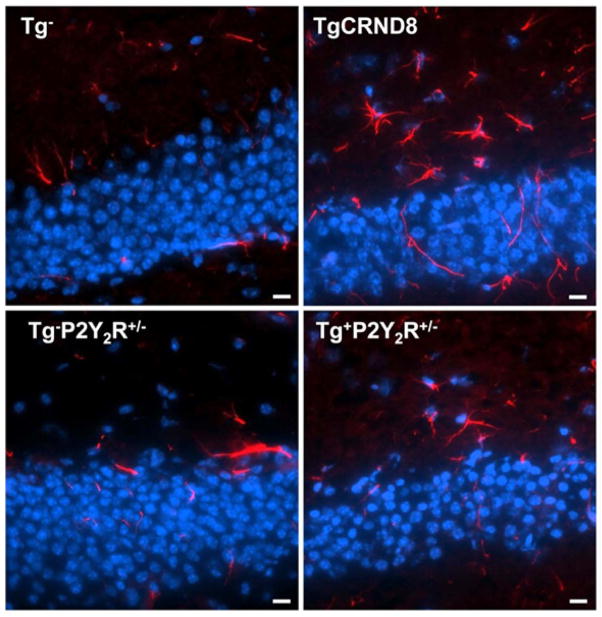

Upregulation and activation of P2Y2Rs in mouse primary microglial cells treated with oligomeric Aβ increased migration of microglial cells towards Aβ and enhanced Aβ uptake and degradation (Kim et al., 2012), a neuroprotective mechanism that could slow disease progression in vivo. Accordingly, heterozygous deletion of P2Y2Rs in TgCRND8 mice decreased the number of CD11b+ and CD45+ (Figure 1) microglial cells surrounding Aβ plaques in the brain, suggesting that a reduction in P2Y2R expression leads to inefficient microglial cell accumulation and activation that would be expected to have negative effects on nerve function (Kim et al., 2012).

Figure 1. Heterozygous knockout of the P2Y2R attenuates CD45+ microglial cell accumulation in the brains of TgCRND8 mice.

Microglial cell activation in the brains of 10-week-old TgCRND8 mice, and a non-transgenic littermate control (Tg−), TgCRND8 mice heterozygous for P2Y2R (Tg+P2Y2R+/−) and non-transgenic littermate control mice heterozygous for P2Y2R (Tg−P2Y2R+/−) were investigated by subjecting hippocampal brain sections to immunofluorescence analysis using anti-CD45 antibody (red) and Hoescht nuclear stain (blue). Results indicate a decrease in microglial cell accumulation in TgCRND8 mouse brain with deletion of the P2Y2R. Images are representative of results from 3 independent experiments and scale bar = 10 μm.

Neurological symptoms

Abnormal reflexes in limb-flexion and paw-clasping are non-specific markers of neurological deficits that have been used to evaluate neurodegeneration in AD and Huntington’s disease (Komatsu et al., 2006; Mangiarini et al., 1996). Impaired posture and gait have been previously reported even in early stages of AD (Pettersson et al., 2002).

P2Y2R deletion in TgCRND8 mice resulted in abnormal limb-flexion and paw-clasping at 10–12 weeks of age (Ajit et al., 2013). However, these symptoms were absent at this age in TgCRND8 mice with a full complement of P2Y2R, suggesting a neuroprotective role for the P2Y2R in AD. Additionally, heterozygous deletion of the P2Y2R in TgCRND8 mice results in loss of motor coordination. Gait analysis using a Noldus CatWalk system indicates that P2Y2R deletion in TgCRND8 mice reduces swing speed (i.e., the speed of the paw while not in contact with the walkway) and stride length (i.e., the distance between successive paw placements), as compared to age-matched TgCRND8 mice. Additionally, the regularity index, a measure of interpaw coordination defined as the number of normal step sequence patterns relative to the number of paw placements, was significantly decreased with heterozygous deletion of the P2Y2R in TgCRND8 mice. These results strongly support the hypothesis that the P2Y2R plays a neuroprotective function in the TgCRND8 mouse model of AD and encourage studies to assess the effects of the deletion of other P2YR subtypes in animal models of neurodegenerative diseases, including AD.

CONCLUSIONS

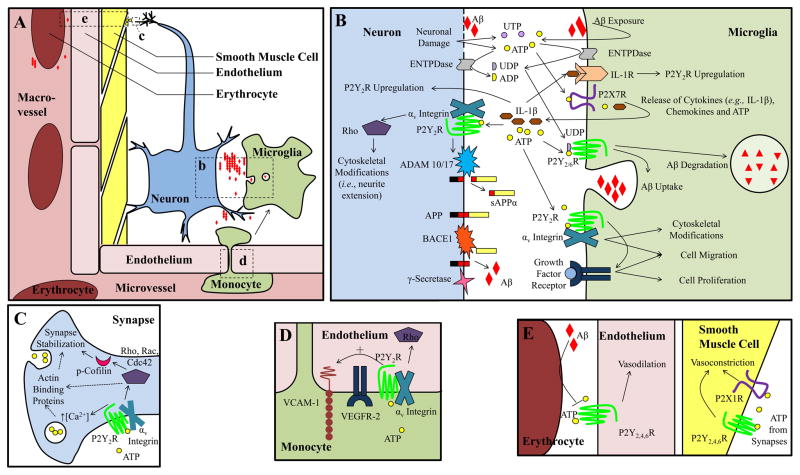

G protein-coupled P2Y nucleotide receptors play a role in neuroinflammation, cerebral blood flow and the progression of many neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, as described in this review. All eight known P2Y receptor subtypes are expressed in the brain where they regulate a variety of neuronal, neuroinflammatory and neurovascular functions, including non-amyloidogenic APP processing, the production of cytokines and chemokines, the migration of microglia, microglial cell-mediated endocytosis and degradation of neurotoxic Aβ, responses to oxidative stress, axonal outgrowth and neurite extension in neurons, the regulation of neurotransmission, and the endothelium-dependent dilation of cerebral blood vessels. Aβ can increase the release of nucleotides from cells and stimulate the upregulation of P2Y receptors. Overall, the collective results from numerous studies suggest that P2YRs can regulate neuroprotective effects, particularly under neuroinflammatory conditions. Therefore, there is considerable interest in targeting P2YRs to prevent the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD. Interestingly, deletion of the P2Y2R in a mouse model of AD accelerates mortality, enhances neurological deficits and Aβ accumulation in the brain and decreases the migration of microglial cells to Aβ plaques (pathways coupled to P2Y2R activation in the brain are shown in Figure 2). Similarly, reduced P2Y2R expression has been reported in post-mortem brain samples from AD patients, as compared to normal controls, suggesting that loss of P2Y2R expression in humans correlates with the AD phenotype. These findings encourage further research to evaluate the contribution of each P2Y receptor subtype to AD progression as a means to develop novel therapeutic approaches to delay the onset and retard pathological manifestations of this debilitating disease that is anticipated to impact 50 million people worldwide within the next few decades.

Figure 2. P2Y receptor function in AD.

A. Overview of cell types involved in neuroinflammation and the neurovascular unit. Areas b–e in panel A are magnified in panels B–E. Although intimately involved, neuron-associated astrocytes and oligodendrocytes and microvessel-associated pericytes are not shown for simplicity. Aβ alters cellular release of nucleotides, including increased ATP release from microglia and decreased ATP release from hypoxic erythrocytes. In perivascular neurons, ATP is released from synaptic vesicles and causes vasoconstriction by activating P2X1 and P2Y2,4,6 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells. P2Y1,2,4,6 receptors in vascular endothelial cells promote vasodilation by responding to ATP in the blood stream. The endothelial P2Y2R facilitates monocyte adhesion to the vascular wall, through VEGFR-2-dependent upregulation of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) as well as monocyte extravasation. Activation of neuronal P2Y1,2 receptors promote neurite extension and stabilization, whereas P2Y13R inhibits neurite extension. Neuronal P2Y2R facilitates non-amyloidogenic processing of APP through ADAM10/17-dependent production of soluble APPα (sAPPα). P2Y1,12,13 receptors enhance glycine transport in the synaptic cleft and P2Y11R activation in glutamatergic neurons delays apoptosis. P2YRs increase dopamine and glutamate release, but can also inhibit neurotransmitter release in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. In microglia, P2Y1,2,6,12,13 receptor activation increases microglial cell migration and P2Y2,6 receptors promote Aβ uptake and degradation. In astrocytes, P2Y1,6 receptors stimulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, P2Y2,4 receptors increase the production and secretion of APP and P2Y14R increases expression of MMP9, which degrades Aβ.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by research grants from the National Institute of Health (NIH grants AG018357 and HL088228) and the BrightFocus Foundation for Alzheimer’s disease research (grant A2013171S).

Abbreviations used

- Aβ

beta-amyloid peptide

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADAM

a disintegrin and metalloprotease

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- BACE1

β-secretase

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- CNS

central nervous system

- EDHF

endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- fAβ

fibrillar Aβ

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- IL

interleukin

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattrant protein-1

- MMP-9

matrix metalloprotease-9

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOX

NADPH oxidase

- oAβ

oligomeric Aβ

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Agresti C, Meomartini ME, Amadio S, Ambrosini E, Volonte C, Aloisi F, Visentin S. ATP regulates oligodendrocyte progenitor migration, proliferation, and differentiation: involvement of metabotropic P2 receptors. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa H, Wakatsuki S, Ishii A, Moriyama K, Sasaki Y, Ohashi K, Sekine-Aizawa Y, Sehara-Fujisawa A, Mizuno K, Goshima Y, Yahara I. Phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase is necessary for semaphorin 3A-induced growth cone collapse. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:367–373. doi: 10.1038/86011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajit D, Woods LT, Camden JM, Thebeau CN, El-Sayed FG, Greeson GW, Erb L, Petris MJ, Miller DC, Sun GY, Weisman GA. Loss of P2Y Nucleotide Receptors Enhances Early Pathology in the TgCRND8 Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;49:1031–1042. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8577-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, Bradt B, Bauer J, Cole GM, Cooper NR, Eikelenboom P, Emmerling M, Fiebich BL, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsop DC, Detre JA, Grossman M. Assessment of cerebral blood flow in Alzheimer’s disease by spin-labeled magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadio S, Montilli C, Magliozzi R, Bernardi G, Reynolds R, Volonte C. P2Y12 receptor protein in cortical gray matter lesions in multiple sclerosis. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:1263–1273. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadio S, Montilli C, Picconi B, Calabresi P, Volonte C. Mapping P2X and P2Y receptor proteins in striatum and substantia nigra: An immunohistological study. Purinergic Signal. 2007;3:389–398. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9069-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadio S, Tramini G, Martorana A, Viscomi MT, Sancesario G, Bernardi G, Volonte C. Oligodendrocytes express P2Y12 metabotropic receptor in adult rat brain. Neurosci. 2006;141:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur DB, Akassoglou K, Insel PA. P2Y2 receptor activates nerve growth factor/TrkA signaling to enhance neuronal differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:19138–19143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505913102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backstrom JR, Lim GP, Cullen MJ, Tokes ZA. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) is synthesized in neurons of the human hippocampus and is capable of degrading the amyloid-beta peptide (1–40) J Neurosci. 1996;16:7910–7919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-07910.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi S, Liao Z, Gonzalez FA, Chorna NE, Seye CI, Weisman GA, Erb L. The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor interacts with alphav integrins to activate Go and induce cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39050–39057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger ME, Harris ME, McDonald DR, Husemann J, Landreth GE. A cell surface receptor complex for fibrillar beta-amyloid mediates microglial activation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2665–2674. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02665.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone E, Di Domenico F, Sultana R, Coccia R, Mancuso C, Perluigi M, Butterfield DA. Heme oxygenase-1 posttranslational modifications in the brain of subjects with Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:2292–2301. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beigi R, Kobatake E, Aizawa M, Dubyak GR. Detection of local ATP release from activated platelets using cell surface-attached firefly luciferase. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C267–278. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.1.C267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, Deane R, Chow N, Long X, Sagare A, Singh I, Streb JW, Guo H, Rubio A, Van Nostrand W, et al. SRF and myocardin regulate LRP-mediated amyloid-beta clearance in brain vascular cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:143–153. doi: 10.1038/ncb1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular mechanisms and blood-brain barrier disorder in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0522-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Yebdri F, Kukulski F, Tremblay A, Sevigny J. Concomitant activation of P2Y(2) and P2Y(6) receptors on monocytes is required for TLR1/2-induced neutrophil migration by regulating IL-8 secretion. Euro J Immunol. 2009;39:2885–2894. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GC, Boarder MR. The effect of nucleotides and adenosine on stimulus-evoked glutamate release from rat brain cortical slices. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:617–623. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergfeld GR, Forrester T. Release of ATP from human erythrocytes in response to a brief period of hypoxia and hypercapnia. Cardiovasc Res. 1992;26:40–47. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boche D, Denham N, Holmes C, Nicoll JA. Neuropathology after active Abeta42 immunotherapy: implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:369–384. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodin P, Burnstock G. Synergistic effect of acute hypoxia on flow-induced release of ATP from cultured endothelial cells. Experientia. 1995;51:256–259. doi: 10.1007/BF01931108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolmont T, Haiss F, Eicke D, Radde R, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Kohsaka S, Jucker M, Calhoun ME. Dynamics of the microglial/amyloid interaction indicate a role in plaque maintenance. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4283–4292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4814-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayden JE. Hyperpolarization and relaxation of resistance arteries in response to adenosine diphosphate. Distribution and mechanism of action. Circ Res. 1991;69:1415–1420. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.5.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller AJ, Gupta S, Parrino TE, Knight AG, Ebenezer PJ, Weidner AM, LeVine H, 3rd, Keller JN, Markesbery WR. NOX activity is increased in mild cognitive impairment. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1371–1382. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos M, Neary JT, Gonzalez FA. P2Y2 nucleotide receptors inhibit trauma-induced death of astrocytic cells. J Neurochem. 2007;103:1785–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling and disorders of the central nervous system. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:575–590. doi: 10.1038/nrd2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Knight GE. Cellular distribution and functions of P2 receptor subtypes in different systems. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;240:31–304. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)40002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Ralevic V. Purinergic signaling and blood vessels in health and disease. Pharmacological Reviews. 2014;66:102–192. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.008029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buvinic S, Briones R, Huidobro-Toro JP. P2Y(1) and P2Y(2) receptors are coupled to the NO/cGMP pathway to vasodilate the rat arterial mesenteric bed. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:847–856. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacabelos R, Alvarez XA, Fernandez-Novoa L, Franco A, Mangues R, Pellicer A, Nishimura T. Brain interleukin-1 beta in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1994;16:141–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo A, Oddo S, Billings LM, Green KN, Martinez-Coria H, Fisher A, LaFerla FM. M1 receptors play a central role in modulating AD-like pathology in transgenic mice. Neuron. 2006;49:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert JA, Atterbury-Thomas AE, Leon C, Forsythe ID, Gachet C, Evans RJ. Evidence for P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y6 and atypical UTP-sensitive receptors coupled to rises in intracellular calcium in mouse cultured superior cervical ganglion neurons and glia. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:525–532. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camden JM, Schrader AM, Camden RE, Gonzalez FA, Erb L, Seye CI, Weisman GA. P2Y2 nucleotide receptors enhance alpha-secretase-dependent amyloid precursor protein processing. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18696–18702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakfe Y, Seguin R, Antel JP, Morissette C, Malo D, Henderson D, Seguela P. ADP and AMP induce interleukin-1beta release from microglial cells through activation of ATPprimed P2X7 receptor channels. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3061–3069. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03061.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Molliver DC, Gebhart GF. The P2Y2 receptor sensitizes mouse bladder sensory neurons and facilitates purinergic currents. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2365–2372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5462-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin Y, Kishi M, Sekino M, Nakajo F, Abe Y, Terazono Y, Hiroyuki O, Kato F, Koizumi S, Gachet C, Hisatsune T. Involvement of glial P2Y(1) receptors in cognitive deficit after focal cerebral stroke in a rodent model. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:95. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HB, Ryu JK, Kim SU, McLarnon JG. Modulation of the purinergic P2X7 receptor attenuates lipopolysaccharide-mediated microglial activation and neuronal damage in inflamed brain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4957–4968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5417-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorna NE, Santiago-Perez LI, Erb L, Seye CI, Neary JT, Sun GY, Weisman GA, Gonzalez FA. P2Y receptors activate neuroprotective mechanisms in astrocytic cells. J Neuroschem. 2004;91:119–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow N, Bell RD, Deane R, Streb JW, Chen J, Brooks A, Van Nostrand W, Miano JM, Zlokovic BV. Serum response factor and myocardin mediate arterial hypercontractility and cerebral blood flow dysregulation in Alzheimer’s phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:823–828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608251104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudio L. Ultrastructural features of the blood-brain barrier in biopsy tissue from Alzheimer’s disease patients. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;91:6–14. doi: 10.1007/s004010050386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N. Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron. 2009;61:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csolle C, Heinrich A, Kittel A, Sperlagh B. P2Y receptor mediated inhibitory modulation of noradrenaline release in response to electrical field stimulation and ischemic conditions in superfused rat hippocampus slices. J Neurochem. 2008;106:347–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha RA, Ribeiro JA, Sebastiao AM. Purinergic modulation of the evoked release of [3H]acetylcholine from the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of the rat: role of the ectonucleotidases. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alimonte I, Ciccarelli R, Di Iorio P, Nargi E, Buccella S, Giuliani P, Rathbone MP, Jiang S, Caciagli F, Ballerini P. Activation of P2X(7) receptors stimulates the expression of P2Y(2) receptor mRNA in astrocytes cultured from rat brain. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2007;20:301–316. doi: 10.1177/039463200702000210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosi N, Iafrate M, Saba E, Rosa P, Volonte C. Comparative analysis of P2Y4 and P2Y6 receptor architecture in native and transfected neuronal systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:1592–1599. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, Kim JV, Zuo Y, Jung S, Littman DR, Dustin ML, Gan WB. ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:752–758. doi: 10.1038/nn1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lorenzo S, Veggetti M, Muchnik S, Losavio A. Presynaptic inhibition of spontaneous acetylcholine release mediated by P2Y receptors at the mouse neuromuscular junction. Neuroscience. 2006;142:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Puerto A, Diaz-Hernandez JI, Tapia M, Gomez-Villafuertes R, Benitez MJ, Zhang J, Miras-Portugal MT, Wandosell F, Diaz-Hernandez M, Garrido JJ. Adenylate cyclase 5 coordinates the action of ADP, P2Y1, P2Y13 and ATP-gated P2X7 receptors on axonal elongation. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:176–188. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuss M, Reiss K, Hartmann D. Part-time alpha-secretases: the functional biology of ADAM 9, 10 and 17. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:187–201. doi: 10.2174/156720508783954686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich HH, Horiuchi T, Xiang C, Hongo K, Falck JR, Dacey RG., Jr Mechanism of ATP-induced local and conducted vasomotor responses in isolated rat cerebral penetrating arterioles. J Vascular Res. 2009;46:253–264. doi: 10.1159/000167273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich HH, Xiang C, Han BH, Zipfel GJ, Holtzman DM. Soluble amyloid-beta, effect on cerebral arteriolar regulation and vascular cells. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsam RT, Kunapuli SP. Central role of the P2Y12 receptor in platelet activation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:340–345. doi: 10.1172/JCI20986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, Lazarowski ER, Kadl A, Walk SF, Park D, Woodson RI, Ostankovich M, Sharma P, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig HK, Eckle T, Mager A, Kuper N, Karcher C, Weissmuller T, Boengler K, Schulz R, Robson SC, Colgan SP. ATP release from activated neutrophils occurs via connexin 43 and modulates adenosine-dependent endothelial cell function. Circ Res. 2006;99:1100–1108. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250174.31269.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M, Ohashi K, Mizuno K. LIM kinase and slingshot are critical for neurite extension. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13692–13702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M, Ohashi K, Sasaki Y, Goshima Y, Niwa R, Uemura T, Mizuno K. Control of growth cone motility and morphology by LIM kinase and Slingshot via phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of cofilin. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2527–2537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02527.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlinge D, Burnstock G. P2 receptors in cardiovascular regulation and disease. Purinergic Signal. 2008;4:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9078-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espada S, Ortega F, Molina-Jijon E, Rojo AI, Perez-Sen R, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Miras-Portugal MT, Cuadrado A. The purinergic P2Y(13) receptor activates the Nrf2/HO-1 axis and protects against oxidative stress-induced neuronal death. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farias M, 3rd, Gorman MW, Savage MV, Feigl EO. Plasma ATP during exercise: possible role in regulation of coronary blood flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1586–1590. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00983.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala M, Zhang L, Gan X, Sherry B, Taub D, Graves MC, Hama S, Way D, Weinand M, Witte M, et al. Amyloid-beta induces chemokine secretion and monocyte migration across a human blood--brain barrier model. Mol Med. 1998;4:480–489. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figge C, Loers G, Schachner M, Tilling T. Neurite outgrowth triggered by the cell adhesion molecule L1 requires activation and inactivation of the cytoskeletal protein cofilin. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2012;49:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester T. Extracellular nucleotides in exercise: possible effect on brain metabolism. J Physiol (Paris) 1978;74:477–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester T, Harper AM, MacKenzie ET, Thomson EM. Effect of adenosine triphosphate and some derivatives on cerebral blood flow and metabolism. J Physiol. 1979;296:343–355. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp013009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke H, Krugel U, Grosche J, Heine C, Hartig W, Allgaier C, Illes P. P2Y receptor expression on astrocytes in the nucleus accumbens of rats. Neuroscience. 2004;127:431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frautschy SA, Yang F, Irrizarry M, Hyman B, Saido TC, Hsiao K, Cole GM. Microglial response to amyloid plaques in APPsw transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:307–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Inoue K. P2Y1 receptor signaling enhances neuroprotection by astrocytes against oxidative stress via IL-6 release in hippocampal cultures. Glia. 2009;57:244–257. doi: 10.1002/glia.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS. Inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:470S–474S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.470S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guns PJ, Korda A, Crauwels HM, Van Assche T, Robaye B, Boeynaems JM, Bult H. Pharmacological characterization of nucleotide P2Y receptors on endothelial cells of the mouse aorta. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:288–295. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guns PJ, Van Assche T, Fransen P, Robaye B, Boeynaems JM, Bult H. Endothelium-dependent relaxation evoked by ATP and UTP in the aorta of P2Y2-deficient mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:569–574. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]