Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) is a major cause of morbidity and late non-relapse mortality following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)1. Sclerodermatous chronic GVHD (scGVHD) is a distinct form of cutaneous GVHD with predominant involvement of skin, subcutaneous tissue and fascia without visceral or vasomotor involvement, and is generally refractory to standard therapies2. Patients with scGVHD have elevated levels of agonistic antibodies against the PDGF receptor and TGF-β, leading to activation of these intracellular pathways3. Imatinib, a first generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), exerts selective dual inhibition of both TGF-β and PDGF pathways. Additionally, imatinib reduces synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins COL1A1, COL1A2 and fibronectin in cultured dermal fibroblasts derived from patients with scGVHD4. Both imatinib and dasatinib have been used to treat patients with steroid refractory scGVHD with promising early results4-6 including correlation with a decline in agonistic PDGFR-α antibodies as measured by a functional fibroblast bioassay7. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that patients exposed to TKI therapy post-HCT would have a decreased incidence of later developing scGVHD.

We retrospectively analyzed the City of Hope database for patients with Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) undergoing allogeneic HCT between 2005 and 2010. Eighty-nine consecutive patients were identified:, 48 Ph+ ALL and 41 CML. Patient and treatment characteristics are shown in Table 1. All patients received mobilized peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs). The median CD34+ cell dose was 5.9×106/Kg (1.5–17.3×106/kg). Most patients received a tacrolimus/sirolimus-based GVHD prophylaxis (82%), with anti-thymocyte globulin used in 10 patients.

Table 1.

Patient & Treatment Characteristics and Outcomes (N=89)

| VARIABLE | All patients (N=89) |

TKI Exposure (n=55) |

TKI non-exposure (n=34) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient gender (Female/Male) | 36(40%) / 53(60%) | 22 (40%) / 33 (60%) | 14 (41%) / 20 (59%) |

| Age (years) at HCT: median (range) | 44 (18 - 62) | 45 (18 - 62) | 41 (20 − 59) |

|

Time (months) from diagnosis to HCT

median (range) |

8.4 (1.8 - 125.9) | 5.5 (1.8 - 125.9) | 18 (3 − 123.1) |

|

Diagnosis

ALL Ph+ CML |

48(54%) 41(46%) |

36 (65%) 19 (35%) |

12 (35%) 22 (65%) |

|

Donor type

Matched Sibling Mismatched Sibling Matched Unrelated Donor Mismatched Unrelated Donor |

48(54%) 1 (1%) 12(14%) 28 (31%) |

33 (60%) 0 (0%) 6 (11%) 16 (29%) |

15 (44%) 1 (3%) 6 (18%) 12 (35%) |

|

Conditioning regimen

Reduced intensity Myeloablative Radiation-based Non-radiation-based |

15(17%) 74(83%) 59 (66%) 30 (34%) |

11 (20%) 44 (80%) 40 (73%) 15 (27%) |

4 (12%) 30 (88%) 19 (56%) 15 (44%) |

|

GVHD prophylaxis

Sirolimus/Tacrolimus-based Tacrolimus/Methotrexate-based Cyclosporine/MMF |

73 (82%) 14(16%) 2(2%) |

46 (85%) 7 (11%) 2 (4%) |

27 (79%) 7 (21%) 0 (0%) |

|

Time (months) to TKI start:

median (range) |

1.9 ( 0.7-17.9) | 1.9 ( 0.7-17.9) | N/A |

|

Duration (months) of TKI exposure*:

median (range) |

9.1 (0.1-89.4) | 9.1 (0.1-89.4) | N/A |

|

Acute GVHD

None Grade I Grade II Grade III Grade IV |

36(40%) 11 (12%) 27 (30%) 12 (14%) 3 (4%) |

24 (43%) 7 (13%) 16 (29%) 7 (13%) 1 (2%) |

12 (35%) 4 (12%) 11 (32%) 5 (15%) 2 (6%) |

|

Chronic GVHD

None Limited Extensive Died Prior to Day +100 |

13(14%) 6 (7%) 64 (72%) 6(7%) |

9 (16%) 5 (9%) 39 (71%) 2 (4%) |

4 (12%) 1 (3%) 25 (73%) 4 (12%) |

|

Sclerodermatous GVHD

Time of Onset Median (months) |

15 (17%) 16.8 (6.7-53.7) |

8 (15%) 13.8 (10.3-33.1) |

7 (21%) 17.1 (6.7-53.7) |

| 2-year Overall Survival | 72.5% ( 95% CI 61.8-80.7) | 73.8% (59.8 − 83.6) | 70.4% (51.9 − 82.8) |

| 2-year Progression-Free Survival | 65.9% (95% CI 54.9- 74.8) | 65.1% (50.9 − 76.2) | 67.3% (48.7 − 80.4) |

|

2-year Relapse/Progression

(cumulative incidence) |

14.8% (95% CI 8.9-24.3) | 22.0% (13.3 − 36.2) | 3.1% (0.4 − 21.1) |

HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; scGVHD, sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease

Duration of exposure defined as start of TKI until discontinuation, last follow-up, or development of scGVHD, whichever occurred first.

Fifty-five patients started TKI therapy at a median of 1.9 months post-HCT (TKI-exposed group)with a median duration of exposure to TKI of 9.1 months. Duration of exposure was defined as the start of TKI until discontinuation, last follow-up, or development of scGVHD, whichever occurred first. Thirty-four patients did not receive TKI therapy (TKI-unexposed group) based on resistance/intolerance to these agents as documented prior to HCT (n=9) or other post-HCT conditions including cytopenias (n=15), acute GVHD (n=3), infections (n=2), abnormal liver enzymes (n=2), early death (n=2) and early TKI discontinuation (n=1).

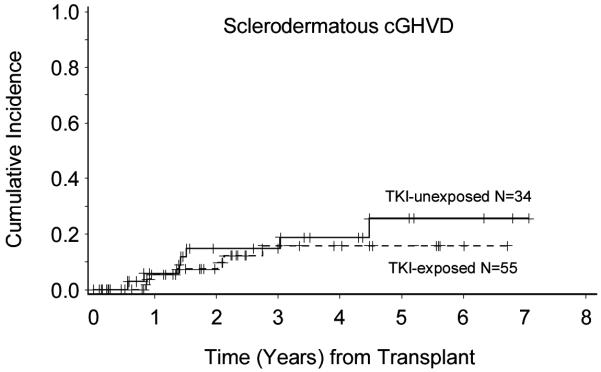

After a median follow-up of 41.4 months (range: 15.6-84.8 months) for surviving patients, 15 total patients developed scGVHD. The cumulative incidence of scGVHD at 2 years for the entire cohort of 89 patients was 10.3% (95%CI: 5.0–17.8%). The 2-year cumulative incidence of scGVHD for the TKI-exposed patients was 7.4% (95%CI: 2.3–16.4%), compared with 14.8% (95%CI: 5.3–29.0) in the TKI-unexposed group (p =0.46) (Figure 1). When considering TKI initiation as a time-dependent variable, the cumulative incidence of scGVHD was not significantly different in TKI-exposed and TKI-unexposed groups [Hazard Ratio 0.76 (95% CI 0.26-2.22) P= 0.61]. The median time of scGVHD onset for TKI-exposed patients was 13.8 months and for unexposed patients was 17.1 months. Three patients developed scGVHD after discontinuation of TKI therapy at 1 month, 7 months and 20 months, respectively.

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of sclerodermatous cGVHD.

Cumulative incidence of scGVHD measured from date of transplant to onset of scGVHD shown in years. The solid line corresponds to patients not exposed to prior TKI therapy (n=34) and the dashed line corresponds to TKI-exposed patients (n=55).

For the entire cohort, the cumulative incidence of cGVHD at 2 years was 75.8% (95%CI: 65.1–83.7%): 76% (95%CI: 61.1–85.8%) for TKI-exposed patients and 76.5% (95%CI: 57.3–87.9%) for TKI-unexposed patients (p=0.86). The median time from HCT to onset of cGVHD was 4.3 months (range 2.3-12.0) in the TKI non-exposed group, and 3.9 months (3.2-22.6) in the TKI-exposed group. There was no difference in median time of cGVHD onset between the TKI- and non-TKI-exposed groups (p=0.91 Wilcoxon). The 2-year overall survival for the entire cohort was 72.5% and 2-year progression-free survival was 65.9%. The 2-year cumulative incidence of relapse was 14.8%. The cumulative incidence of acute GVHD at 100 days was 58.4%, with grade III/IV aGVHD seen in 17% of the patients.

We performed Cox univariate analysis to look for associations between onset of scGVHD and TKI exposure, as well as other variables as reported in the literature. We found no significant association between incidence of scGVHD and TKI exposure. Likewise, TKI exposure was not significantly associated with acute or chronic GVHD. The only statistically significant association with incidence of scGVHD was HLA mismatch. Patients with mismatched donors were three times more likely to develop scleroderma compared to patients with matched donors [HR 3.2 (95% CI: 1.1-9.2), p=0.03]. Since HLA disparity was the only significant variable associated with development of scGVHD, multivariate analysis was not necessary.

Our overall incidence of scGVHD in the TKI exposed group was similar to previously published results. Inamoto et al. reported a cumulative incidence of scGVHD among patients with chronic GVHD requiring systemic steroids as 7% at initial diagnosis of cGVHD and 20% at 3 years8. Skert el al. showed a 5-year cumulative incidence of scGVHD of 11.5% in all patients and 15.5% in those who developed cGVHD9. Martires et al. reported a 52% incidence of scleroderma among patients with refractory cGVHD treated at their center10. Risk factors significantly associated with scGVHD in these studies included exposure to total body irradiation (>400cGy), use of PBSCs, peripheral eosinophillia, presence of autoimmune markers, decline in forced vital capacity, and skin involvement with cGVHD. In our cohort of patients, Cox univariate analysis detected an association between HLA mismatch and scGVHD but saw no correlation between radiation exposure or other factors and subsequent development of scleroderma. These differences could be due to factors such as patient population (% CML) and GVHD prophylactic regimens for the Inamoto series8, proportion of patients receiving bone marrow grafts in the Skert series9, and referral bias in the Martires series10.

In summary, we observed no clear differences in the incidence of cGVHD or scGVHD between TKI-exposed and unexposed patients in our study. However, our results must be interpreted with caution due to the heterogeneity of the cohort, the small sample size and the inherent selection biases of retrospective studies. The overall incidence of scGVHD in patients receiving TKI post-HCT appeared similar to previously published reports8, 9. In light of emerging data showing the efficacy of TKIs in treatment of established cGVHD and scGVHD, it may be useful to conduct prospective studies of TKIs for prevention of scGVHD, especially in high-risk patients such as HLA-mismatched HCT recipients.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Socie G, Stone JV, Wingard JR, Weisdorf D, Henslee-Downey PJ, Bredeson C, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Late Effects Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. N Engl J Med. 1999;3411:14–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gratwohl AA, Moutsopoulos HM, Chused TM, Akizuki M, Wolf RO, Sweet JB, et al. Sjogren-type syndrome after allogeneic bone-marrow transplantation. Ann. Intern. Med. 1977;876:703–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-6-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Distler JH, Jungel A, Huber LC, Schulze-Horsel U, Zwerina J, Gay RE, et al. Imatinib mesylate reduces production of extracellular matrix and prevents development of experimental dermal fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;561:311–22. doi: 10.1002/art.22314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magro L, Mohty M, Catteau B, Coiteux V, Chevallier P, Terriou L, et al. Imatinib mesylate as salvage therapy for refractory sclerotic chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;1143:719–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen GL, Arai S, Flowers ME, Otani JM, Qiu J, Cheng EC, et al. A phase 1 study of imatinib for corticosteroid-dependent/refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease: response does not correlate with anti-PDGFRA antibodies. Blood. 2011;11815:4070–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez-Ortega I, Servitje O, Arnan M, Orti G, Peralta T, Manresa F, et al. Dasatinib as salvage therapy for steroid refractory and imatinib resistant or intolerant sclerotic chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;182:318–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivieri A, Cimminiello M, Corradini P, Mordini N, Fedele R, Selleri C, et al. Long-term outcome and prospective validation of NIH response criteria in 39 patients receiving imatinib for steroid-refractory chronic GVHD. Blood. 2013;12225:4111–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-494278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inamoto Y, Storer BE, Petersdorf EW, Nelson JL, Lee SJ, Carpenter PA, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of sclerosis in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2013;12125:5098–103. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-464198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skert C, Patriarca F, Sperotto A, Cerno M, Fili C, Zaja F, et al. Sclerodermatous chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: incidence, predictors and outcome. Haematologica. 2006;912:258–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martires KJ, Baird K, Steinberg SM, Grkovic L, Joe GO, Williams KM, et al. Sclerotic-type chronic GVHD of the skin: clinical risk factors, laboratory markers, and burden of disease. Blood. 2011;11815:4250–4257. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-350249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]