Abstract

Biting midges in the genus Culicoides are important vectors of arboviral diseases, including epizootic hemorrhagic disease, bluetongue, and likely Schmallenberg, which cause significant economic burden worldwide. Research on these vectors has been hindered by the lack of a sequenced genome, the difficulty of consistent culturing of certain species, and the absence of molecular techniques such as RNA interference (RNAi). Here, we report the establishment of RNAi as a research tool for the adult midge, Culicoides sonorensis. Based on previous research and transcriptome analysis, which revealed putative siRNA pathway member orthologs, we hypothesized that adult C. sonorensis midges have the molecular machinery needed to preform RNA silencing. Injection of control dsRNA, dsGFP, into the hemocoel 2–3 day old adult female midges resulted in survival curves that support virus transmission. DsRNA injection targeting the newly identified C. sonorensis inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (CsIAP1) ortholog, resulted in a 40% decrease of transcript levels and 73% shortened median survivals as compared to dsGFP-injected controls. These results reveal the conserved function of IAP1. Importantly, they also demonstrate the feasibility of RNAi by dsRNA injection in adult midges, which will greatly facilitate studies of the underlying mechanisms of vector competence in C. sonorensis.

Keywords: biting midge, vector-borne disease, orbivirus, reverse genetics

Introduction

Biting midge species within the genus Culicoides (family: Cetratopogonidae) vector economically significant arboviruses, including bluetongue (BTV, orbivirus), epizootic hemorhagic disease (EHDV, orbivirus), and Schmallenberg (Bunyaviridae). While not affecting human health, these viral diseases cause fatalities in several ruminant species including cattle, sheep and goat livestock (Garigliany et al., 2012, Mellor et al., 2000). Disease control is focused on host-based methods, including vaccinations against BTV/EHDV, as well as control of livestock movement and housing (Maclachlan & Mayo, 2013). In addition, several potential vector-based control strategies, such as breeding site removal, repellents, traps, and insecticides have been evaluated (summarized in Carpenter et al., 2008). Despite the positive impact of surveillance and preventative measures on disease transmission, the potential economic losses due to a BTV outbreak would be substantial and could benefit significantly from long-term cost-effective vector control strategies (Calistri et al., 2004, Giovannini et al., 2004).

Novel control strategies, based on detailed molecular understanding of vector-pathogen interactions or biology of the vector species, have been proposed and are being implemented for Culicidae (e.g. Fu et al., 2010, Hoffmann et al., 2012). However, similar molecular studies into the biology and vector competence of Culicoides midges are hindered by many factors. These factors include lack of laboratory colonies for the vast majority of Culicoides vector species, sequence information, and molecular and genetic protocols. In addition, their minute size severely limits the amount of protein or nucleic acids that can be obtained from an individual, and challenges their fine-scale manipulations. This knowledge gap can be shortened, most easily, in C. sonorensis, the major vector of BTV in North America (Tabachnick, 1996), as it is one of the two species for which robust colonies and cell lines exist (Nayduch et al., 2014a). In addition, a number of transcriptome studies have been published (Campbell et al., 2005, Campbell & Wilson, 2002), most recently using RNAseq data (Nayduch et al., 2014b). Some of these C. sonorensis gene products are potential targets for new vector control strategies, but require gene function analysis on the molecular level.

A central molecular tool to study gene function in non-model organisms is targeted gene knockdown by RNA interference (RNAi), which degrades mRNAs through the endogenous small interfering (si)RNA pathway in a sequence-specific manner. Reverse genetic analyses by so-called environmental RNAi depends on the ability of tissues to uptake an exogenous molecular trigger, either long dsRNA or siRNAs (Winston et al., 2007), and the function of Dicer2, R2D2 and AGO2 (most recently reviewed in (Wilson & Doudna, 2013). A recent study revealed that RNAi can be induced by exogenous dsRNA in a larval cell line of C. sonorensis (Schnettler et al., 2013). However, based on studies in other insect species (Terenius et al., 2011) these results may not be a good predictor of environmental RNAi success in the whole organism. This study therefore aims to test the efficacy of environmental RNAi in adult female C. sonorensis midges by assessing the knockdown phenotype of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP)1. Knockdown of this conserved gene in other insect species results in increased apoptosis and decreased lifespan (Hay et al., 1995, Walker III & Allen, 2011, Wang et al., 2012), and thus is a potential target to interrupt viral transmission in C. sonorensis.

Results

Adult midges encode and express components of the siRNA pathway

Previous work demonstrated that a cloned C. sonorensis cell line was capable of environmental RNAi, and provided support for the potential application of reverse genetics in this species. As the first step to examine whether a functional siRNA pathway exists in adult C. sonorensis, we queried the recently published transcriptome (Nayduch et al., 2014b). Using Aedes aegypti siRNA pathway protein sequences as queries, multiple C. sonorensis transcripts with sequence similarity to AGO2, Dicer2, and R2D2 were identified by best reciprocal Blast hits. Overall, this analysis identified three AGO2, one Dicer2, and two R2D2 putative orthologous sequences (Table 1, alignments to mosquito orthologs are shown in Figure S1).

Table 1.

Putative C. sonorensis siRNA pathway members. For sequence alignments, please see Figure S1

| Protein |

Culicoides sonorensis |

Length [AA] |

Anopheles gambiae |

Length [AA] |

Aedes aegypti | Length [AA] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGO2 | GAWM01012834 | 269 | AGAP011537-PA | 841 | AAEL017251-RA | 992 |

| GAWM01012835 | 633 | |||||

| GAWM01012837 | 254 | |||||

| Dicer2 | GAWM01016560 | 1679 | AGAP012289-PA | 1673 | AAEL006794-RA | 1659 |

| R2D2 | GAWM01013568 | 295 | AGAP009887-PA | 325 | AAEL011753-RA | 319 |

| GAWM01017705 | 334 |

Each of the three partial transcripts identified as AGO2 mapped to amino acids 242–786 of the Ae. aegypti ortholog (AAEL017251-RA). The amino acid sequence identity between the three C. sonorensis AGO2 sequences was very high, ranging from 88–97 %. In contrast, both sequences orthologous to R2D2 spanned the entire Ae. aegypti R2D2 protein sequence (AAEL011753-RA), and showed sequence divergence between them, with only 36% sequence identity and a unique N-terminal extension of 21 amino acids encoded by the GAWM1017705 transcript. Finally, the in silico translated single putative C. sonorensis Dicer2 transcript aligned to the complete Ae. aegypti Dicer2 protein (AAEL006794-RA), with 46% amino acid identity. Taken together, these data suggested strongly that a functional siRNA pathway was present in adult midges that may be exploited for RNA interference by provision of exogenous dsRNA.

Delivery of dsRNA into adult C. sonorensis

Intrathoracic injection is the most direct means of dsRNA delivery and has been used successfully in multiple insect species to induce RNAi (recently reviewed by Scott et al. 2013). Injection requires immobilization of insects by either cold treatment (Harris et al., 1965) or exposure to CO2 (Blandin et al., 2002).

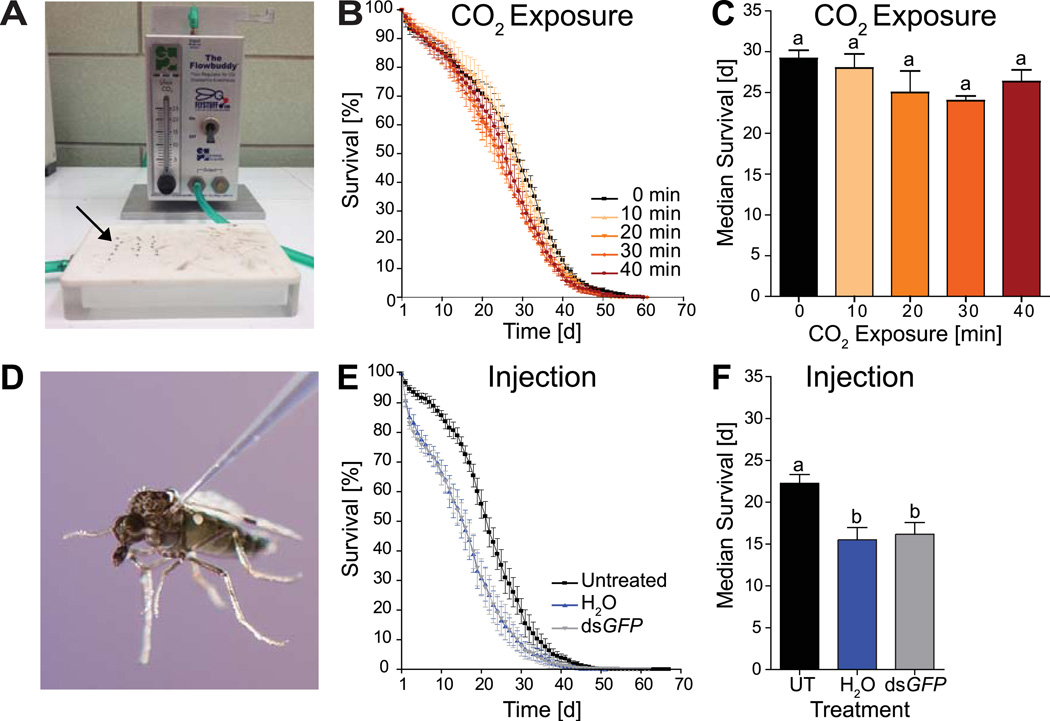

Despite several attempts of cold treatment using either a cold plate or ice, we were unable to immobilize C. sonorensis females sufficiently to allow for injection. Placement of adult female midges on a Flypad (Figure 1A) and exposure to constant CO2 levels at 7 l/min immobilized adult midges within 30 s. After CO2 exposure, all midges recovered completely and were motile within 10 min. To determine possible long term detrimental effects of CO2 exposure on midge survival, 2–4 d old adult C. sonorensis were placed under a constant flow of 7 l/min CO2 for 0, 10, 20, 30, and 40 min. Analysis of survival by Kaplan-Meier revealed statistically significant differences based on CO2 exposure (Log-Rank test, P<0.0001; Figure 1B, see Figure S1 for individual replicates). However, these difference were small with hazard ratios of 1.316 (1.153–1.501 95% CI) when comparing the longest CO2 exposures to untreated controls. In addition, CO2 treatment did not affect median survival (One-way ANOVA, P=0.2348, Tukey’s post test, P>0.05; Figure 1C). Given these results, we deemed CO2 exposure as the method of choice for C. sonorensis injection.

Figure 1. Delivery of dsRNA by microinjection to adult midges.

(A–C) Effects of CO2 exposure on C. sonorensis adults. (A) Midges (arrow) were immobilized using a Flypad. (B) Survival curves of midges after exposure to CO2 at indicated time intervals. (C) Comparison of median survival after CO2 exposures. Lettering denotes lack of statistically significant differences (Tukey’s post test, P>0.05). Data were combined from three biological replicates (Figure S2), and are presented as mean ± one standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). (D–F) Effects of injection on C. sonorensis adult females. (D) Female midges were injected intrathoracically into the soft cuticle between wing base and the second pleural sclerite. (E) Graph depicts survival curves of midges after no, H2O, or dsGFP injection. (F) Midge median survival after injection treatments. Statistically significant differences are indicated by different letters (Tukey’s post test, P<0.05). All data are presented as mean ± one S.E.M. from six biological replicates (Figure S3). UT; untreated control

Next, we examined the intrathoracic injection volume delivered into adult midges using a hand-held microinjector. Injected volumes of up to 50 nl lead to complete fluid retention using a single injection under the wing base (Figure 1D). To determine the extent of injury through the injection process, a control dsRNA, dsGFP, or its vehicle, ddH2O, were injected into adult midges. Survival was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier, revealing accelerated mortality in both treatment groups as compared to untreated controls (Log Rank test, P<0.0001; Figure 1E, see Figure S3 for individual replicates). Injection also shortened median survival by 6–8 d (One-way ANOVA, P=0.2348, Tukey’s post test, P<0.05; Figure 1F). Hazard ratios of 1.433 (1.229–1.581 95% CI) due to dsGFP injection and 2.159 (1.912–2.438 95% CI) due to H2O injection indicated that increased mortality rates, in part, were caused by injury and potentially exacerbated by the vehicle due to osmotic shock (Figure S3). Nevertheless, average lifespan of dsGFP injected midges exceeded 17 days and demonstrated the feasibility of this dsRNA injection protocol using dsGFP as a reliable negative control.

Identification of C. sonorensis IAP1 ortholog

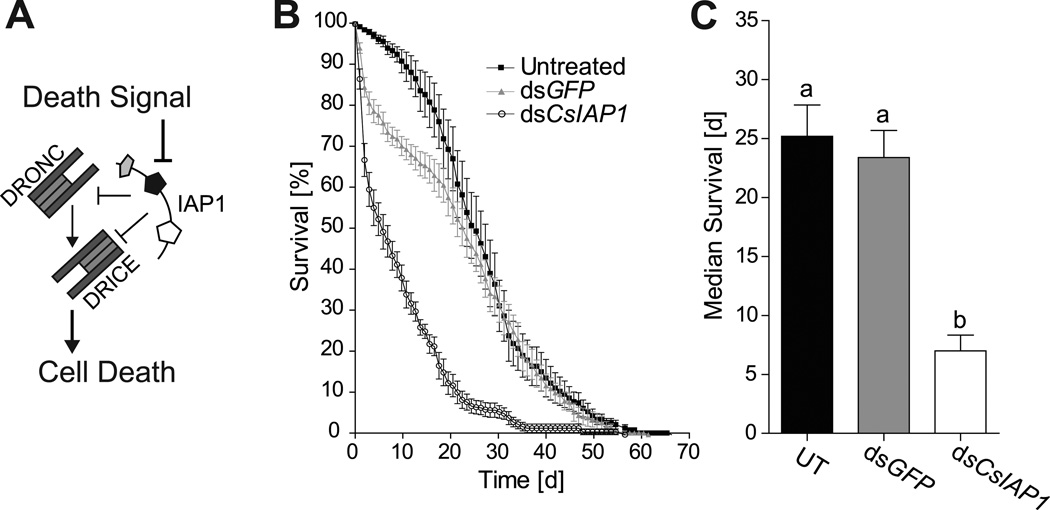

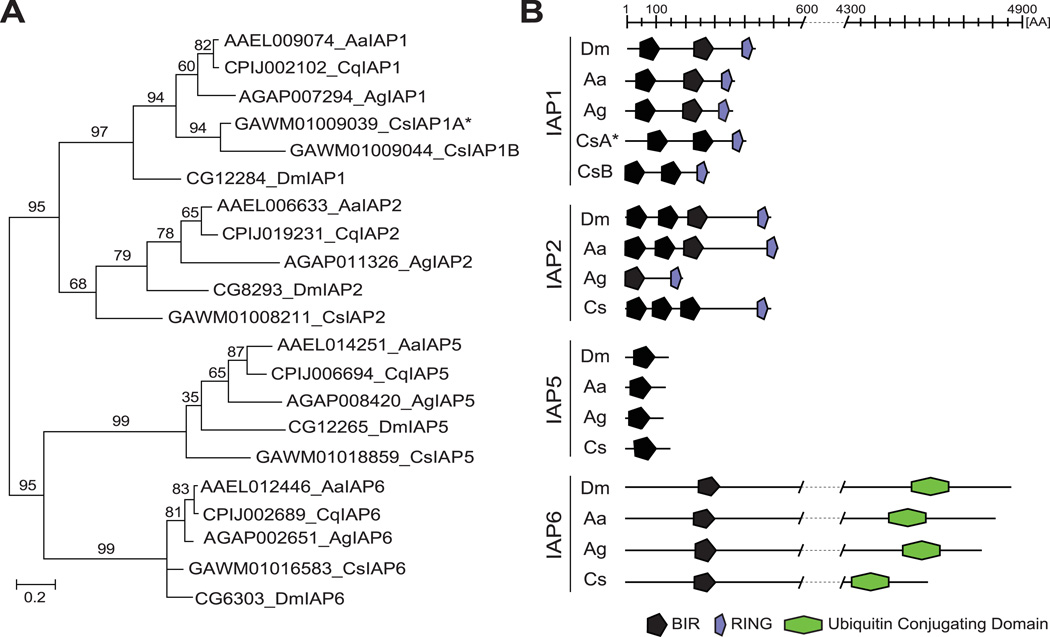

Inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (IAP1) regulates apoptosis by inhibiting caspases, which are essential for cell death (Figure 3A). Since inhibition of IAP1 results in increased cell death and mortality, this protein has been discussed as a potential target for insect pest control by RNAi (Zhang et al., 2013). To identify an ortholog of IAP1 in C. sonorensis, Dipteran IAP protein sequences were attained from ImmunoDB (http://cegg.unige.ch/Insecta/immunodb) and used to query the C. sonorensis transcriptome. We recovered five full-length transcripts that encoded putative IAPs. To determine orthology, their deduced amino acid sequences and known IAPs from Ae. aegypti (Aa), An. gambiae (Ag), Culex quinquefaciatus (Cq), and D. melanogaster (Dm) were used to reconstruct their phylogenetic relationships by maximum likelihood (Figure 2A, see Figure S4 for sequences). In general, the tree topology for IAP1, 2, 5, and 6 mirrored the phylogenetic relationships among the five species (Wiegmann et al., 2011). Clusters for IAP2, 5, and 6 contained a single protein from each species, while two potential C. sonorensis IAP1 orthologs were found (CsIAP1A, CsIAP1B). Similar results were obtained after performing the phylogenetic analysis using alignments of the individual BIR domains (Figure S5, see Figure S6 for sequences). Protein domain analysis further corroborated the phylogenetic analysis and identified the expected number and location of BIRs, RINGs and Ubiquitin-conjugating domains required for the function of each protein (Figure 2B).

Figure 3. Effects of dsCsIAP1 injection on female C. sonorensis mortality.

A) Illustration of the IAP1’s regulatory function of apoptosis through caspase (D. melanogaster DRONC and DRICE) inhibition. B) Graph represents percent survival of midges after no, dsGFP, or dsCsIAP1 injection. C) Median survival of midges after corresponding treatments. Statistically-significant differences are indicated by different letters (Tukey’s post test, P<0.05). Data are presented as mean ± one S.E.M. from five biological replicates (Figure S9). UT; untreated control

Figure 2. Identification of Culicoides IAP orthologs.

(A) Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of Dipteran IAPs. IAPs are identified by their accession number, species abbreviation, and IAP subfamily. (B) Schematic representation of IAP proteins indicating the length and location of functional domains including BIR (black pentagon), RING (purple narrow pentagon), and Ubiquitin Conjugating domain (green hexagon). Corresponding total protein sequences are listed in Figure S4, and BIR domain sequences are listed in Figure S6.

Aa, Ae. aegypti; Ag, An. gambiae; Cq, C. quinquefasiatus; Cs, C. sonorensis; Dm, D. melanogaster; * putative functional ortholog of IAP1 in C. sonorensis used for further analysis.

To further discriminate between the two putative orthologs of IAP1 in C. sonorensis, alignments of CsIAP1A/B were inspected. CsIAP1B lacks the DXXD motif and contains a truncated linker region between BIR1 and BIR2 (Figure 2B, and Figure S7), which are required for IAP1 function (Ditzel et al., 2003, Sun et al., 1999). Based on these findings, CsIAP1A (GAWM01009039; CsIAP1) was chosen as the target for further analysis.

Targeted knockdown of CsIAP1 by dsRNA injection in adult midges

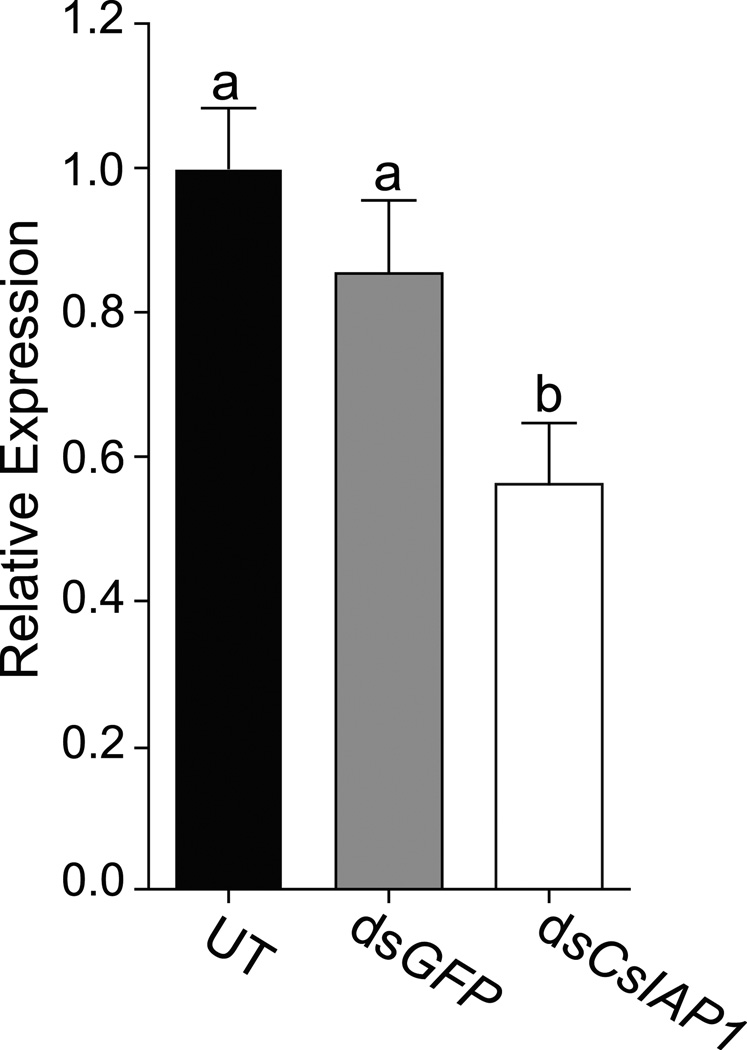

IAP1 regulates apoptosis by inhibiting initiator and effector caspases, called DRONC and DRICE in D. melanogaster (Figure 3A), for which we identified putative orthologs in the C. sonorensis transcriptome (Figure S8). Depletion of IAP1 by RNAi was shown previously to increase mortality in Lygus lineolaris and Ae. aegypti (Walker III & Allen, 2011, Wang et al., 2012). To test if GAWM01009039 is indeed IAP1, dsRNA targeting CsIAP1 (dsCsIAP1) was injected into adult midges, and survival was monitored daily. As expected, injection of dsCsIAP1 resulted in a significant increase in mortality rates and decreased life span when compared to both untreated and dsGFP-injected midges (Log-Rank test, P<0.0001; Figure 3B, see Figure S9 for individual replicates). DsCsIAP1- injected midges were twice as likely to die as compared to dsGFP- treated controls (Log Rank test, P<0.0001; Hazard ratio=2.098), and their median survival was reduced three-fold to 7 days post injection (1-Way ANOVA, P<0.0001, Tukey’s post test P<0.05, Figure 3C). Transcript levels of CsIAP1 were determined by qRT-PCR 5 dpi. Elongation factor 1b (EF1b, GAWM01010754) was used as the reference gene, as its expression remains constant during multiple physiological processes (Nayduch et al., 2014b). CsIAP1 expression was reduced by 40% in dsCsIAP1-treated midges relative to both dsGFP-injected and untreated midges (1-Way ANOVA, P<0.001, Newman-Keuls post test P<0.05; Figure 4). These decreased transcript levels specific to dsCsIAP1-injection demonstrate that dsRNA targeted knockdown can be utilized in adult C. sonorensis.

Figure 4. Relative expression of CsIAP1 transcripts after dsRNA injection.

Graph depicts CsIAP1 mean transcript levels at 5 dpi for dsGFP and dsCsIAP1-injected midges relative to untreated controls. QRT-PCR results were analyzed using EF1b as reference gene and untreated midges as calibrator condition. Statistically significant differences are indicated by different letters (Newman-Keuls post test, P<0.05). Data are presented as mean ± one S.E.M., from four biological replicates (Figure S2). UT; untreated control

Discussion

Over the last 15 years, RNAi has become the standard genetic tool for gene function analysis in non-model insect species. It also harbors the promise of highly species-specific insect control both for agricultural and public health purposes. The canonical siRNA pathway is characterized by three key proteins: Dicer2 and R2D2, which are required to process long dsRNA into 21 nt siRNAs, as well as AGO2, which forms the protein core of the RISC complex and cleaves the single-stranded target (recently reviewed in RNA (Wilson & Doudna, 2013). Based on available transcriptome data, we identified their putative orthologs in C. sonorensis. The high percent identities amongst the three putative AGO2 proteins strongly suggest that these transcripts are from a single gene, and sequence differences are likely the result of haplotype variation within the midge laboratory strain. In contrast, R2D2 has potentially undergone gene duplication in the midge lineage. Of the two putative R2D2 proteins, we hypothesize that GAWM01013568 has retained function required for siRNA pathway activity.

To develop RNAi as a molecular tool for C. sonorensis, we chose dsRNA injection as the delivery method to avoid inconsistent dose uptake due to variable feeding volumes or degradation by digestive enzymes (Arimatsu et al., 2007). In addition, injection disseminates dsRNA through hemolymph circulation, allowing direct contact between dsRNA and all midge tissues. Immobilization for intrathoracic injection is essential and can be achieved in insects through cold treatment or CO2 exposure (Harris et al., 1965). The inability of adult C. sonorensis to be immobilized by cold plate was an interesting observation, and may be a result of their ability to overwinter at low temperatures as larvae (Barnard & Jones, 1980). In contrast, CO2 exposure immobilized adult midge effectively and over prolonged periods of time with barely measureable adverse effects on their survival.

Not surprisingly, injury due to injection accelerated midge mortality rates. However, increased mortality rates were usually limited to the first three to five days post injection, suggesting that by five days the surviving midges had overcome initial injury by wound healing. This period was followed by decreased daily mortality rates as compared to untreated controls, which resulted in roughly similar median survival between injected and control groups. Importantly, the lifespan of dsGFP-injected midges supports the BTV intrinsic incubation period, which is between 4–20 days depending on temperature (Foster et al., 1968; Purse et al., 2005). This protocol thus enables the study of the molecular basis of arbovirus-midge interactions by reverse genetics.

As proof of principle, we targeted CsIAP1 for knockdown by dsRNA injection in adult female midges. IAP1 is a key regulator of apoptosis (Hay et al., 1995, Tenev et al., 2007), which functions in persistent viral infection as well as antiviral defense in insects (reviewed in (Clarke & Clem, 2003). Apoptosis affects virus replication in multiple insect cell lines (Settles & Friesen, 2008, Wang et al., 2008). Furthermore, cytopathic apoptosis in a mammalian cell line caused by BTV infection is hindered by expression of recombinant Ae. aegypti IAP1 (Li et al., 2007). These published data suggest that regulation of apoptosis could be integral for persistent virus infection within the midge vector. Putative orthologs of both initiator and effector caspases inhibited by IAP1 are expressed in adult midges, further supporting that the core of the apoptosis pathway is conserved in C. sonorensis.

As expected, injection of dsCsIAP1 into adult female midges lead to accelerated mortality rates, a conserved phenotype observed previously in hemiptera (Walker III & Allen, 2011) and mosquitoes (Wang et al., 2012). Given that CsIAP1 transcript levels were significantly and specifically reduced, this phenotype is in all likelihood the result of RNAi triggered by the injection of long dsRNAs. In some cases, the RNAi trigger is amplified and propagated through endogenous production and release of siRNAs (Winston et al., 2002). However, very few insect species are capable of this so-called systemic RNAi (Tomoyasu et al., 2008). The 40% transcript reduction of CsIAP1 induced by a comparatively high dose of dsRNA (Miller et al., 2012) suggests that the initial RNAi trigger is not amplified in C. sonorensis. Similar results have been obtained from closely related Culicidae (Blandin et al., 2002, Zhu et al., 2003). Nevertheless, our data clearly demonstrate that environmental RNAi in C. sonorensis can be exploited for gene function analysis. Determining average transcript reduction levels across other C. sonorensis genes requires further empirical assessment, as knockdown levels are influenced by a multitude of factors, including species, tissue, target gene, as well as temperature (recently reviewed in (Scott et al., 2013).

RNAi has evolved as a fundamental antiviral immune response and affects virus replication in insect vectors (Olson et al., 1996, (Bronkhorst & van Rij, 2014). The demonstration of an active siRNA pathway in adult female midges dictates that replication of arboviruses with dsRNA genomes, such as BTV and EHDV must overcome this defense mechanism. One hypothesis is that during infection BTV escapes RNA silencing due to the release of only positive sense capped mRNA transcripts into the cytosol and sequestration of dsRNA genome to the inner viral capsid (Roy, 2008). In addition, the BTV core has a high affinity for dsRNA, effectively trapping and concealing it from host detection (Diprose et al., 2002). Nevertheless, engineered dsRNA specific for BTV non-structural protein 1 limits virus replication in a C. sonorensis cell line (Schnettler et al., 2013). Studies are currently underway to determine the contribution of the siRNA pathway to biting midge vector competency in vivo.

Taken together, this study provides the first demonstration of RNAi in adult C. sonorensis midges providing a much needed means to study this important arbovirus vector species. With the development of an intrathoracic injection protocol and delivery of long dsRNAs, we verify the conserved function of CsIAP1 as a negative regulator of cell death in adult midges. The decreased life span of dsIAP1-treated midges ablates virus transmission, and thus may be exploited for novel disease control strategies targeting the vector. In addition, we provide annotation of siRNA and apoptosis pathway components in C. sonorensis enabling future studies on their role in vector competence for arboviruses.

Experimental Procedures

Insect Rearing and maintenance

The C. sonorensis AK strain was reared as described previously (Jones & Foster, 1974). At 1–3 d post-eclosion, midges were immobilized with CO2 (Flypad, Flowbuddy Benchtop Regulator; Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA, USA) then counted and sexed. Adults were maintained on sugar water (8% fructose in 2.5 mM 4-aminobenzoic acid) at 21–25°C and 70% relative humidity, with a photoperiod of 12:12 (L:D) h. Midges were allowed to recover for 1–2 d before performing experiments, and returned to the rearing conditions described above.

Sequence alignment, Phylogenetic analysis, and Protein Domain identification

Amino acid sequence alignments were performed in MEGA 6.0 (Tamura et al., 2013) using ClustalW (Larkin et al., 2007) with default settings. To reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships, Maximum likelihood trees were generated using MEGA 6.0, with the following settings: Bootstrap method with 1,000 iterations, Jones-Taylor-Thorton substitution model, complete gap deletions, and nearest-neighbor-interchange. Protein domains were identified by means of the ScanProsite tool (http://prosite.expasy.org/scanprosite/; de Castro et al., 2006).

Total RNA extraction

Midges were frozen and stored at −80 °C prior to RNA extraction. Frozen midges (n=20) were homogenized in 200 µl homogenized Trizol (Ambion, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and total RNA was extracted using a final volume of 1 ml Trizol according to manufacturer instructions. Pellets were air dried and resuspended in 100 µl RNAse-free water (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA was purified with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) using the standard protocol and eluted in 50 µl RNAse-free water. RNA integrity was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and concentration determined by Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). On average, 17–21 ng of total RNA was obtained per midge.

cDNA synthesis

C. sonorensis cDNA was synthesized from 100 ng of purified total RNA with iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA), using oligo(dT) and random hexamer primers, in a total reaction volume of 20 µl, following manufacturer’s protocol.

double-stranded (ds)RNA Synthesis

Template for dsRNA synthesis was generated by two-round PCR initially using 100 ng of cDNA. Primers for first round PCR (25 µl total reaction volume) were as follows: dsCsIAP1_F 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGTTGAAGAACACTTGAGATGG -3′; dsCsIAP1_R 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGCCAATCTTCATACGACACC-3′. The resulting PCR product was purified by gel extraction (QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit; Qiagen). Next, 1 µl of first round PCR product was then amplified in a 50 ul second round PCR reaction using T7 primers: T7_F 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′; T7_R 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′. PCR product from these reactions was precipitated using 1 volume of isopropanol and resuspended in deionized water.

DsGFP (An et al., 2010) and dsCsIAP1 were synthesized as described previously (An et al., 2010) using 1 µg of second round PCR template in a total reaction volume of 20 µl. Purified dsRNA was resuspended in RNase-free water at a final concentration of 3 µg/µl.

Injection of adult female C. sonorensis

Midges were anesthetized under a constant flow of CO2 (7 l/min). Female midges (n=100 per treatment and replicate) were injected with 50 nl H2O, dsGFP, or dsCsIAP1 under the wing base using a nanoinjector (Nanoject II, Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA, USA). Injection needles were made from borosilicate capillaries (3.5”, outer diameter = 1.143 mm, inner diameter = 0.0531 mm, Drummond Scientific) using a Micropipette Puller (P-97, Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA, USA) and following pulling protocol: H* = 546, V =160, P = 170, T = 133 (*setting specific to each filament; instrument). Needles were opened by clipping the tip with scissors, and dsRNA was front-filled using the nanoinjector.

Survival analysis

After injection, survival was monitored daily until all midges within the experiment had died. Resulting data were analyzed and graphed using Kaplan-Meier and compared using the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test and Hazard ratios. Median survival data were evaluated statistically with 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Multiple Comparison post test. Biological replicates for CO2 exposure (N = 3), injection (N = 6), and CsIAP1 knockdown (N = 5) were performed. All statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism software version 5.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Quantitative (q)RT-PCR

Female midges (n = 20 per treatment and replicate) were collected 5 d post injection (dpi) for expression analysis. QRT-PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Biorad) according to manufacturer’s protocol with 1 µl of diluted cDNA (1:2) as template for each 20 µl volume reaction. QPCRs were executed on the StepOnePlus RT-PCR System and analyzed with the StepOne Software 2.0 (Life Technologies) with the following amplification protocol: initial cycle of 5 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 1 min at 59°C, and 1 min at 72°C (detection). Primers, designed using the Beacon Design 8 (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA, USA), were as follows: CsIAP1_F 5′-TTGTGGACATATTATTGCCTGTG-3′; CsIAP1_R 5′-CATGACTTTCGTGAATGGTTGT- 3′; EF1b_F 5′-ATCCGTGAAGAACGTCTCAAA- 3′; EF1b_R 5′-CATGGCTTAACTTCGAGGATG-3′.

Fold change for each treatment (dsGFP or dsCsIAP1) was assessed using a modified ΔΔCt method (Pfaffl, 2001), which takes potentially different primer efficiencies (Figure S10) into account. All qRT-PCRs were performed with 3 technical and four biological replicates. Expression data between treatments were compared statistically with 1-way ANOVA, followed by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison post test. All statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism software version 5.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Lee Cohnsteadt, Mr. James A. Kempert, and Mr. William E. Yarnell at the Arthropod-Borne Animal Disease Research Unit, USDA-ARS, Manhattan, KS for provision of all adult C. sonorensis midges and housing materials used in this study. We further thank Drs. Rollie Clem and W. Bart Bryant, Division of Biology, Kansas State University, for helpful discussions on IAP1. This is contribution no. 15-093-J from the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station. Research reported in this publication was supported by NIAID of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AI095842 (K.M.), and by Specific Cooperative Agreement 58-5430-1360 to K. M. from the USDA Agricultural Research Service. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

References

- An C, Budd A, Kanost MR, Michel K. Characterization of a regulatory unit that controls melanization and affects longevity of mosquitoes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;68:1929–1939. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0543-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimatsu Y, Kotani E, Sugimura Y, Furusawa T. Molecular characterization of a cDNA encoding extracellular dsRNase and its expression in the silkworm,Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard DR, Jones RH. Culicoides variipennis: seasonal abundance, overwintering, and voltinism in northeastern Colorado. Environmental Entomol. 1980;9:709–712. [Google Scholar]

- Blandin S, Moita LF, Kocher T, Wilm M, Kafatos FC, Levashina EA. Reverse genetics in the mosquitoAnopheles gambiae: targeted disruption of the Defensin gene. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:852–856. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronkhorst AW, van Rij RP. The long and short of antiviral defense: small RNA-based immunity in insects. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;7c:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calistri P, Giovannini A, Conte A, Nannini D, Santucci U, Patta C, Rolesu S, Caporale V. Bluetongue in Italy: Part I. Vet Ital. 2004;40:243–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CL, Vandyke KA, Letchworth GJ, Drolet BS, Hanekamp T, Wilson WC. Midgut and salivary gland transcriptomes of the arbovirus vectorCulicoides sonorensis(Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) Insect Mol Biol. 2005;14:121–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2004.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CL, Wilson WC. Differentially expressed midgut transcripts inCulicoides sonorensis(Diptera: ceratopogonidae) following Orbivirus (reoviridae) oral feeding. Insect Mol Biol. 2002;11:595–604. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2002.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter S, Mellor PS, Torr SJ. Control techniques forCulicoides biting midges and their application in the U.K. and northwestern Palaearctic. Med Vet Entomol. 2008;22:175–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke TE, Clem RJ. Insect defenses against virus infection: the role of apoptosis. Int Rev Immunol. 2003;22:401–424. doi: 10.1080/08830180305215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro E, Sigrist CJ, Gattiker A, Bulliard V, Langendijk-Genevaux PS, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A, Hulo N. ScanProsite: detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W362–W365. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diprose JM, Grimes JM, Sutton GC, Burroughs JN, Meyer A, Maan S, Mertens PP, Stuart DI. The core of bluetongue virus binds double-stranded RNA. J Virol. 2002;76:9533–9536. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9533-9536.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzel M, Wilson R, Tenev T, Zachariou A, Paul A, Deas E, Meier P. Degradation of DIAP1 by the N-end rule pathway is essential for regulating apoptosis. Nature Cell Biol. 2003;5:467–473. doi: 10.1038/ncb984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu G, Lees RS, Nimmo D, Aw D, Jin L, Gray P, Berendonk TU, White-Cooper H, Scaife S, Kim Phuc H, Marinotti O, Jasinskiene N, James AA, Alphey L. Female-specific flightless phenotype for mosquito control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4550–4554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000251107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garigliany MM, Bayrou C, Kleijnen D, Cassart D, Jolly S, Linden A, Desmecht D. Schmallenberg virus: a new Shamonda/Sathuperi-like virus on the rise in Europe. Antiviral Res. 2012;95:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini A, Calistri P, Nannini D, Paladini C, Santucci U, Patta C, Caporale V. Bluetongue in Italy: Part II. Vet Ital. 2004;40:252–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RL, Hoffman RA, Frazar ED. Chilling vs. Other Methods of Immobilizing Flies. 1965;58:379–380. [Google Scholar]

- Hay BA, Wassarman DA, Rubin GM. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell. 1995;83:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, Montgomery BL, Popovici J, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson PH, Muzzi F, Greenfield M, Durkan M, Leong YS, Dong Y, Cook H, Axford J, Callahan AG, Kenny N, Omodei C, McGraw EA, Ryan PA, Ritchie SA, Turelli M, O'Neill SL. Successful establishment ofWolbachia inAedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature. 2011;476:454–457. doi: 10.1038/nature10356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RH, Foster NM. Oral infection ofCulicoides variipennis with bluetongue virus: development of susceptible and resistant lines from a colony population. J Med Entomol. 1974;11:316–323. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/11.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Li H, Blitvich BJ, Zhang J. TheAedes albopictusinhibitor of apoptosis 1 gene protects vertebrate cells from bluetongue virus-induced apoptosis. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16:93–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclachlan NJ, Mayo CE. Potential strategies for control of bluetongue, a globally emerging, Culicoides-transmitted viral disease of ruminant livestock and wildlife. Antiviral Res. 2013;99:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor PS, Boorman J, Baylis M. Culicoides biting midges: their role as arbovirus vectors. Annu Rev Entomol. 2000;45:307–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.45.1.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SC, Miyata K, Brown SJ, Tomoyasu Y. Dissecting systemic RNA interference in the red flour beetleTribolium castaneum: parameters affecting the efficiency of RNAi. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayduch D, Cohnstaedt LW, Saski C, Lawson D, Kersey P, Fife M, Carpenter S. StudyingCulicoides vectors of BTV in the post-genomic era: resources, bottlenecks to progress and future directions. Virus Res. 2014a;182:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayduch D, Lee MB, Saski C. The reference transcriptome of the adult female biting midge (Culicoides sonorensis) and differential gene expression profiling during teneral, blood, and sucrose feeding conditions. PLOS ONE. 2014b doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098123. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KE, Higgs S, Gaines PJ, Powers AM, Davis BS, Kamrud KI, Carlson JO, Blair CD, Beaty BJ. Genetically engineered resistance to dengue-2 virus transmission in mosquitoes. Science. 1996;272:884–886. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purse BV, Mellor PS, Rogers DJ, Samuel AR, Mertens PP, Baylis M. Climate change and the recent emergence of bluetongue in Europe. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:171–181. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy P. Functional mapping of bluetongue virus proteins and their interactions with host proteins during virus replication. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2008;50:143–157. doi: 10.1007/s12013-008-9009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnettler E, Ratinier M, Watson M, Shaw AE, McFarlane M, Varela M, Elliott RM, Palmarini M, Kohl A. RNA interference targets arbovirus replication inCulicoides cells. J Virol. 2013;87:2441–2454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02848-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JG, Michel K, Bartholomay LC, Siegfried BD, Hunter WB, Smagghe G, Zhu KY, Douglas AE. Towards the elements of successful insect RNAi. J Insect Physiol. 2013;59:1212–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles EW, Friesen PD. Flock house virus induces apoptosis by depletion ofDrosophila inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein DIAP1. J Virol. 2008;82:1378–1388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01941-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Cai M, Gunasekera AH, Meadows RP, Wang H, Chen J, Zhang H, Wu W, Xu N, Ng SC, Fesik SW. NMR structure and mutagenesis of the inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein XIAP. Nature. 1999;401:818–822. doi: 10.1038/44617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick WJ. Culicoides variipennis and bluetongue-virus epidemiology in the United States. Annu Rev Entomol. 1996;41:23–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.41.010196.000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. 2013 doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenev T, Ditzel M, Zachariou A, Meier P. The antiapoptotic activity of insect IAPs requires activation by an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1191–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terenius O, Papanicolaou A, Garbutt JS, Eleftherianos I, Huvenne H, Kanginakudru S, Albrechtsen M, An C, Aymeric JL, Barthel A, Bebas P, Bitra K, Bravo A, Chevalier F, Collinge DP, Crava CM, de Maagd RA, Duvic B, Erlandson M, Faye I, Felfoldi G, Fujiwara H, Futahashi R, Gandhe AS, Gatehouse HS, Gatehouse LN, Giebultowicz JM, Gomez I, Grimmelikhuijzen CJ, Groot AT, Hauser F, Heckel DG, Hegedus DD, Hrycaj S, Huang L, Hull JJ, Iatrou K, Iga M, Kanost MR, Kotwica J, Li C, Li J, Liu J, Lundmark M, Matsumoto S, Meyering-Vos M, Millichap PJ, Monteiro A, Mrinal N, Niimi T, Nowara D, Ohnishi A, Oostra V, Ozaki K, Papakonstantinou M, Popadic A, Rajam MV, Saenko S, Simpson RM, Soberon M, Strand MR, Tomita S, Toprak U, Wang P, Wee CW, Whyard S, Zhang W, Nagaraju J, Ffrench-Constant RH, Herrero S, Gordon K, Swevers L, Smagghe G. RNA interference in Lepidoptera: an overview of successful and unsuccessful studies and implications for experimental design. J Insect Physiol. 2011;57:231–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoyasu Y, Miller SC, Tomita S, Schoppmeier M, Grossmann D, Bucher G. Exploring systemic RNA interference in insects: a genome-wide survey for RNAi genes inTribolium. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R10. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker III WB, Allen ML. RNA interference-mediated knockdown of IAP inLygus lineolaris induces mortality in adult and pre-adult life stages. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 2011;138:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Blair CD, Olson KE, Clem RJ. Effects of inducing or inhibiting apoptosis on Sindbis virus replication in mosquito cells. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2651–2661. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/005314-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Gort T, Boyle DL, Clem RJ. Effects of manipulating apoptosis on Sindbis virus infection of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. J Virol. 2012;86:6546–6554. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00125-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegmann BM, Trautwein MD, Winkler IS, Barr NB, Kim JW, Lambkin C, Bertone MA, Cassel BK, Bayless KM, Heimberg AM, Wheeler BM, Peterson KJ, Pape T, Sinclair BJ, Skevington JH, Blagoderov V, Caravas J, Kutty SN, Schmidt-Ott U, Kampmeier GE, Thompson FC, Grimaldi DA, Beckenbach AT, Courtney GW, Friedrich M, Meier R, Yeates DK. Episodic radiations in the fly tree of life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5690–5695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012675108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RC, Doudna JA. Molecular mechanisms of RNA interference. Annu Rev Biophys. 2013;42:217–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston WM, Molodowitch C, Hunter CP. Systemic RNAi in C. elegans requires the putative transmembrane protein SID-1. Science. 2002;295:2456–2459. doi: 10.1126/science.1068836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston WM, Sutherlin M, Wright AJ, Feinberg EH, Hunter CP. Caenorhabditis elegans SID-2 is required for environmental RNA interference. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10565–10570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611282104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Li HC, Miao XX. Feasibility, limitation and possible solutions of RNAi-based technology for insect pest control. Insect Sci. 2013;20:15–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Chen L, Raikhel AS. Posttranscriptional control of the competence factor betaFTZ-F1 by juvenile hormone in the mosquitoAedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13338–13343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234416100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.