Abstract

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) catalyzes trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) and its demethylation is catalyzed by UTX. EZH2 levels are frequently elevated in breast cancer and have been proposed to control gene expression through regulating repressive H3K27me3 marks. However, it is not fully established whether breast cancers with different levels of H3K27me3, EZH2 and UTX exhibit different biological behaviors. Levels of H3K27me3, EZH2 and UTX and their prognostic significance were evaluated in one hundred forty six (146) cases of breast cancer. H3K27me3 levels were higher in HER2-negative samples. EZH2 expression was higher in cancers that were LN+, size > 20mm, and with higher tumor grade and stage. Using a Cox regression model, H3K27me3 levels and EZH2 expression were identified as independent prognostic factors for overall survival for all the breast cancers studied as well as the ER-positive subgroup. The combination of low H3K27me3 and high EZH2 expression levels were significantly associated with shorter survival. UTX expression was not significantly associated with prognosis and there were no correlations between H3K27me3 levels and EZH2/UTX expression. To determine if EZH2 is required to establish H3K27me3 marks in mammary cancer, Brca1 and Ezh2 were deleted in mammary stem cells in mice. Brca1-deficient mammary cancers with unaltered H3K27me3 levels developed in the absence of EZH2, demonstrating that EZH2 is not a mandatory H3K27 methyltransferase in mammary neoplasia and providing genetic evidence for biological independence between H3K27me3 and EZH2 in this tissue.

Keywords: histone modification, EZH2, UTX, cancer, prognosis

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in Korean women and represents 16% of all female cancers [1]. Cancer, including breast cancer, was initially thought to arise mainly through genetic alterations, such as mutations and chromosomal abnormalities. However, it has become apparent that epigenetic alterations are frequently causally linked to hematopoietic malignancies [2] and possibly epithelial cancers [3].

The Polycomb group protein enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), which exhibits methyltransferase activity, is a critical regulator of cell type identity and stem cell activity [4]. Elevated levels of EZH2 have been observed in human bladder, breast, colon and prostate cancers [5] and are defined as a validated marker of aggressiveness and poor outcome in breast cancer [6]. EZH2 is described as involved in expansion of mammary stem cells and a bi-lineage identity in basal cancer stem cells [6-8]. In contrast, loss-of-function mutations in EZH2 have been linked to hematopoietic malignancies in humans and mice [9,10]. EZH2 together with SUZ12 and EED form the polycomb repressive complex 2 that catalyzes trimethylation of lysine 27 of histone H3 (H3K27me3). This leads to recruitment of other polycomb complexes, DNA methyltransferases, and histone deacetylases resulting in transcriptional repression and chromatin compaction [5]. In lymphomas, somatic mutations of EZH2 result in an increase of H3K27me3 levels associated with suppression of gene expression [11]. However, increased expression of EZH2 does not necessarily correlate with increased H3K27me3 levels in breast cancer [12]. Therefore, it remains unresolved whether altered EZH2 levels in cancer result in an aberrant H3K27me3 pattern, and whether this might be subject to tissue- and cancer-specificities.

The discovery of the H3K27me3 demethylase UTX revealed that removal of H3K27me3 also is under active control. UTX is a component of the mixed-lineage-leukemia 2/3 complex that also promotes histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation [13,14]. H3K4 methylation is a marker of open and actively transcribed chromatin [15]. Inactivating somatic mutations of UTX in human cancers suggest UTX as a tumor suppressor gene acting through transcriptional control mechanisms [16]. However, there is a lack of correlation between global H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 levels with UTX mutation and the mechanism of UTX-mediated tumor suppression remains unclear.

Global histone modifications are associated with specific breast cancer subtypes and an important role in breast cancer progression has been proposed [17]. Estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer comprises approximately 75% of all breast cancers. In these cancers treatments targeting either ER (such as tamoxifen) or estrogen synthesis (aromatase inhibitors) are effective adjuvant therapies. However, up to 30% of patients treated with tamoxifen can exhibit resistance to this agent [7]. Identification of the subgroup of ER+ breast cancer patients with poorer prognosis may allow us to determine if they also represent a group more likely to demonstrate resistance to antihormonal agents. In this study, we investigated the relationship between global levels of H3K27me3, EZH2 and UTX protein expression and defined their predictive value in all types of breast cancers represented in the cohort as well as specifically in the ER+ subgroup. A genetic study utilizing a Brca1-deficient mouse model was performed to test whether or not EZH2 was mandatory for H3K27me3 in mammary cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case selection

Tissue microarrays containing a total of 146 cases of invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) (stage I-III) treated between April 1997 and December 2002 were provided by the Chonnam National University, Hwasun Hospital National Biobank of Korea, a member of the National Biobank of Korea supported by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Family Affairs. All samples collected were used with informed consent under protocols approved by the institutional review board. The mean age of the cases was 46 years (range, 21-89). Clinical follow-up data including overall survival were available for all cases. Sixty-nine percent of cancers were ER+, 15% were human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positive, 47% were lymph node positive, 66% were > 20 mm and 38% were grade 3. Patients were treated with endocrine therapy (69%), adjuvant chemotherapy (84%) and radiation therapy (54%). The mean observation time for overall survival was 6.2 years (range, 0.1–11.6) with 31 deaths from breast cancer during this time. Details of the characteristics of this study are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient tumor characteristics

| Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range), years | 46 (21 - 89) | |

| Mean follow-up (range), years | 6.2 (0.1 - 11.6) | |

| Number of breast cancer deaths (%) | 31 (21.2) | |

| Breast cancer-specific 5-year survival (%) | 117 (80) | |

|

| ||

| Number (%) | ||

|

| ||

| ER status | Negative | 44 (30.1) |

| Positive | 102 (69.9) | |

| HER2 status | Negative | 123 (84.2) |

| Positive | 23 (15.8) | |

| Node status | Negative | 76 (52.1) |

| Positive | 70 (47.9) | |

| Tumor size | ≤20 mm | 49 (33.6) |

| >20 mm | 97 (66.4) | |

| Tumor grade | 1 | 19 (13.0) |

| 2 | 71 (48.6) | |

| 3 | 56 (38.4) | |

| Tumor Stage | I | 22 (15.1) |

| II | 80 (54.8) | |

| III | 44 (30.1) | |

| H3K27me3 | Low | 76 (52.1) |

| High | 70 (47.9) | |

| EZH2 | Low | 74 (50.7) |

| High | 72 (49.3) | |

| UTX | Low | 84 (57.5) |

| High | 62 (42.5) | |

Tissue microarray (TMA) construction

Arrays were constructed with a 1.5mm punch on a Beecher arrayer (Beecher Instruments, Sun Prairie, WI). The array layout in grid format was designed using Microsoft Excel. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of IDC were reviewed and the area of interest marked out on the slide. Using a marker pen, the corresponding region was circled on the archival ‘donor’ paraffin block. The samples were then arrayed on to a ‘recipient’ blank block. Each sample was arrayed in triplicate to minimize tissue loss and overcome tumor heterogeneity.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Automated IHC staining was performed using the Bond-max system (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL), which is able to process up to 30 slides at a time. The slides carrying the tissue sections cut from paraffin-embedded tissue microarray blocks were labeled and baked for 1 hour at 60°C. The slides were then covered by Bond Universal Covertiles (Leica Microsystems) and placed into the Bond-max instrument. All subsequent steps were performed by the automated instrument according to the manufacturer‘s instructions (Leica Microsystems), in the following order: (1) deparaffinization of the tissue slides with Bond Dewax Solution (Leica Microsystems) at 72°C for 30 minutes; (2) heat-induced epitope retrieval (antigen unmasking) with Bond Epitope Retrieval Solution 1 (Leica Microsystems) for 20 minutes at 100°C; (3) peroxide block placement on the slides for 5 minutes at ambient temperature; and (4) incubation with ER (1:35, clone 1D5, Dako), PGR (1:50, clone PgR 636, Dako), HER2 (1:250, Dako), EZH2 (1:50, Cell Signaling), UTX (1:100, Sigma) and H3K27me3 (1:50, Cell Signaling) primary antibodies, for 15 minutes at ambient temperature; (5) incubation with Post Primary reagent (Leica Microsystems) for 8 minutes at ambient temperature, followed by washing with Bond Wash solution (Leica Microsystems) for 6 minutes; (6) Bond Polymer (Leica Microsystems) placement on the slides for 8 minutes at ambient temperature, followed by washing with Bond Wash and distilled water for 4 minutes; (7) color development with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride chromogen for 10 minutes at ambient temperature; and (8) hematoxylin counterstaining for 5 minutes at ambient temperature, followed by mounting of the slides. Normal human serum served as a negative control. Tissue microarrays were digitized (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA) and immunoreactivity was evaluated.

Evaluation of IHC staining

Two pathologists (Lee JS and Kim Y) independently performed blinded assessments of the IHC staining. Cases were considered positive for ER or PGR when strong nuclear staining was observed in at least 10% of tumor cells tested. HER2 immunostaining was considered positive when strong (3+) membranous staining was observed in at least 30% of tumor cells, whereas cases with 0 to 2+ were regarded as negative. Both intensity and proportion of positive nuclei were assessed for H3K27me3, EZH2 and UTX IHC. Intensity values ranged between 1 and 3, with 1 being weak, and 3 strong. Proportion scores ranged between 1 and 10, with 1 representing 1-10% positive nuclei, and 10 representing 91-100% positive nuclei. Negative staining was scored as 0. A score that ranged from 0 to 30 was calculated as the product of the intensity and proportion scores. Each tumor was represented three times on the TMAs and an average was calculated among the three scores [12]. The same cutoff point was used for analysis of associations and outcome for expression levels with the median score utilized for all proteins (3 for EZH2, 2 for UTX and 12 for H3K27me3). Thus, categories of high and low expression were consistently defined as groups with scores above or below/equal to the median score used for each group.

Generation of mice carrying deletions of Brca1 and Ezh2 in mammary epithelium

Brca1f/f mice [18] heterozygous for Trp53 were crossed with Ezh2f/f;MMTV-CreA to generate female mice with a Ezh2 and Brca1 deficient mammary epithelium on a germ-line Trp53 haploinsufficient background. Genotyping was confirmed by PCR of DNA extracted from ear skin. All experiments and procedures were performed according to a protocol approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Immunofluorescence and special stains

Cancer and mammary tissues of Ezh2 and Brca1 mutant mice were removed and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Five micrometer sections were prepared for H&E staining and immunofluorescence analyses using primary antibodies for detection of EZH2 (5246S, Cell Signaling), H3K27me3 (07-449, Millipore), ER (SC-542, Santa Cruz) and E-cadherin (610182, BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Associations between markers and clinicopathological features were assessed using Pearson’s chi-square test and Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Survival analyses were stratified by ER status to account for the fact that ER expression fundamentally defines clinically distinct prognostic groups in breast cancer [19]. The log-rank test was used to compare survival between groups in Kaplan-Meier survival plots. Association with breast cancer-specific survival was estimated using a Cox proportional-hazards model, providing an estimate of the hazard ratio (HR) and a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for each variable. All tests were two-sided and considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS (v.18).

RESULTS

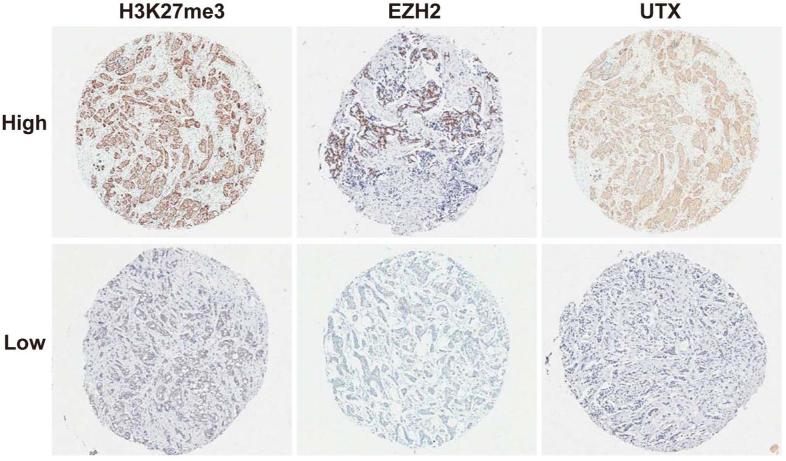

Correlation of H3K27me3 and EZH2 levels with clinicopathological parameters

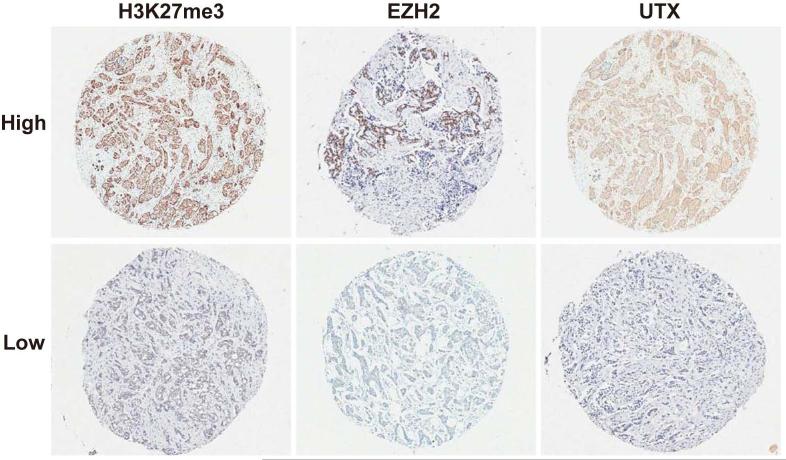

EZH2 is considered the mandatory methyltransferase to establish H3K27me3 epigenetic marks but little is known about the correlation of EZH2 expression with H3K27me3 level in breast cancer subtypes. To explore this question, EZH2 levels and the degree of H3K27me3 were initially analyzed in human breast cancer specimen. Representative IHC staining of H3K27me3, EZH2 and UTX are shown in Figure 1. The average score of H3K27me3 was 12.8 ± 6.8, EZH2 was 4.9 ± 5.1 and UTX was 3.7 ± 4.7. Associations between levels of H3K27me3, EZH2 and different clinicopathological parameters for the entire cohort of breast cancers studied are presented in Table 2. Strong staining was associated with HER2 negativity (p=0.006). High EZH2 was associated with lymph node positivity (p=0.032), larger tumor size (p=0.031), higher tumor grade (p=0.001) and stage (p=0.004). However, no clinical parameter was significantly associated with UTX expression. Correlations between levels of H3K27me3 and EZH2/UTX were investigated. No significant correlation was observed between H3K27me3 and EZH2 (Spearman correlation 0.01). However, there was a positive correlation between and UTX expression (Spearman correlation 0.31, p=0.001), a result that could be considered contrary to the known function of UTX as H3K27me3 demethylase.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of breast tumors for H3K27me3, EZH2 and UTX. Shown are representative examples of low and high expression, respectively.

Table 2.

Correlation of H3K27me3, EZH2 and UTX with clinicopathological variables

| No. of cases |

H3K27me3 | EZH2 | UTX | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Low | High | p-value | Low | High | p-value | Low | High | p-value | ||

| ER status | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Negative | 44 | 24 | 20 | 0.692 | 17 | 27 | 0.056 | 30 | 14 | 0. 087 |

| Positive | 102 | 52 | 50 | 57 | 45 | 54 | 48 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Her2 status | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Negative | 123 | 58 | 65 | 0.006 | 66 | 57 | 0.097 | 67 | 56 | 0.830 |

| Positive | 23 | 18 | 5 | 8 | 15.0 | 17 | 6 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Node status | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Negative | 76 | 40 | 36 | 0. 884 | 45 | 31 | 0.032 | 39 | 37.0 | 0. 113 |

| Positive | 70 | 36 | 34 | 29 | 41.0 | 45 | 25 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Tumor size | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| ≤20 mm | 49 | 26 | 23 | 0.863 | 31 | 18 | 0.031 | 26 | 23 | 0.437 |

| <20 mm | 97 | 50 | 47 | 43 | 54 | 58 | 39 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Tumor grade | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 1 | 19 | 9 | 10 | 0.891 | 15 | 4 | 0.001 | 8 | 11 | 0.387 |

| 2 | 71 | 38 | 33 | 40 | 31 | 49 | 22 | |||

| 3 | 56 | 29 | 27 | 19 | 37 | 27 | 29 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Tumor stage | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| I | 22 | 12 | 10 | 0.861 | 16 | 6 | 0.004 | 12 | 10 | 0.404 |

| II | 80 | 40 | 40 | 44 | 36 | 43 | 37 | |||

| III | 44 | 24 | 20 | 14 | 30 | 29 | 15 | |||

Survival analysis based on H3K27me3 and EZH2 levels

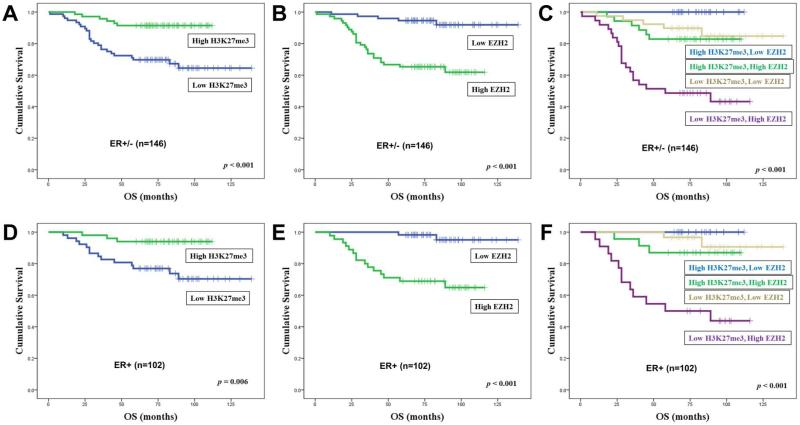

Univariate analyses showed that H3K27me3, EZH2 and UTX were strongly associated with overall survival (OS) irrespective of ER status (Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 1). In ER+ cancers, survival analysis including log rank testing and Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that high H3K27me3 (p<0.001, log-rank; Figure 2D) and low EZH2 (p<0.001, log-rank; Figure 2E) were associated with longer OS. To further analyze the relationship between the pattern of low H3K27me3 staining and high EZH2 expression, breast cancers were stratified into four groups (low H3K27me3, high EZH2; low H3K27me3, low EZH2; high H3K27me3, high EZH2; high H3K27me3, low EZH2) and OS was analyzed. OS was significantly shorter for patients with low H3K27me3 and high EZH2 compared to the other groups (p<0.001, log-rank; Figure 2C and F). The median OS of low H3K27me3 and high EZH2 group was only 45 months.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves based on abundance of H3K27me3 and EZH2. Overall survival plots stratified by high or low expression of H3K27me3 and EZH2 in all cases (A, B, C). Overall survival plots stratified by high or low expression of H3K27me3 and EZH2 in ER-positive cancers (D, E, F).

Multivariate survival analysis was performed to evaluate the independence of H3K27me3, EZH2 and UTX expression as a prognostic factor. H3K27me3 and EZH2 levels demonstrated independent prognostic influences when included together with multiple known prognostic variables such as ER status, HER2 status, lymph node status, tumor size and tumor stage (Table 3). Low H3K27me3 staining was also significantly associated with unfavorable OS (HR 0.18, 95% CI 0.07-0.49, p=0.001). High expression of EZH2 was associated with poorer survival (HR 3.34, 95% CI 1.20-9.27, p=0.021). Significantly even in the ER+ group, H3K27me3 (HR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06-0.72, p=0.013) and EZH2 expression (HR 6.31, 95% CI 1.42-28.13, p=0.016) demonstrated independent prognostic influences when included together with HER2 status, lymph node status, tumor size and tumor stage. Next, the prognostic value of combining H3K27me3 and EZH2 was evaluated. In multivariate analyses, low H3K27me3 and high EZH2 had independent prognostic significance both in the entire cohort (HR 2.57, 95% CI 1.63-4.04, p=0.001) and the ER+ subgroup (HR 2.78, 95% CI 1.52-5.09, p=0.001; Supplemental Table 2).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis with prognostic factors for overall survival

| Variables | Entire cohort of breast cancers (n=146) | ER-positive (n=102) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| ER+ | 0.30 | 0.13 - 0.71 | 0.006 | |||

| Her2+ | 0.66 | 0.27 - 1.60 | 0.354 | NA | ||

| LN+ | 1.24 | 0.22 - 7.05 | 0.810 | NA | ||

| Size > 20mm | 1.77 | 0.39 - 7.96 | 0.460 | NA | ||

| Tumor stage | 8.10 | 2.03 - 39.81 | 0.004 | 11.76 | 2.70 - 51.23 | 0.001 |

| H3K27me3 high | 0.18 | 0.07 - 0.49 | 0.001 | 0.21 | 0.06 - 0.72 | 0.013 |

| EZH2 high | 3.34 | 1.20 - 9.27 | 0.021 | 6.31 | 1.42 - 28.13 | 0.016 |

| UTX high | 0.68 | 0.27 - 1.74 | 0.423 | NA | ||

BRCA1-dependent mouse mammary tumors and H3K27me3 are unaltered upon loss of Ezh2

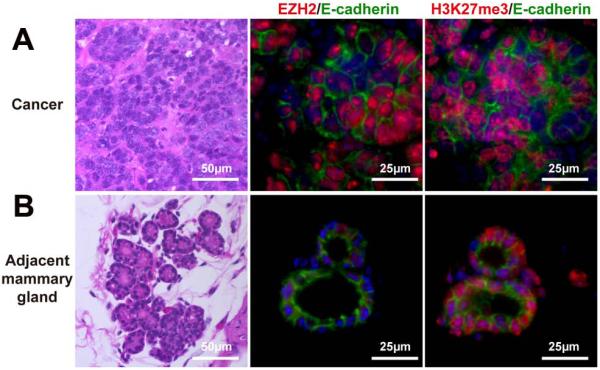

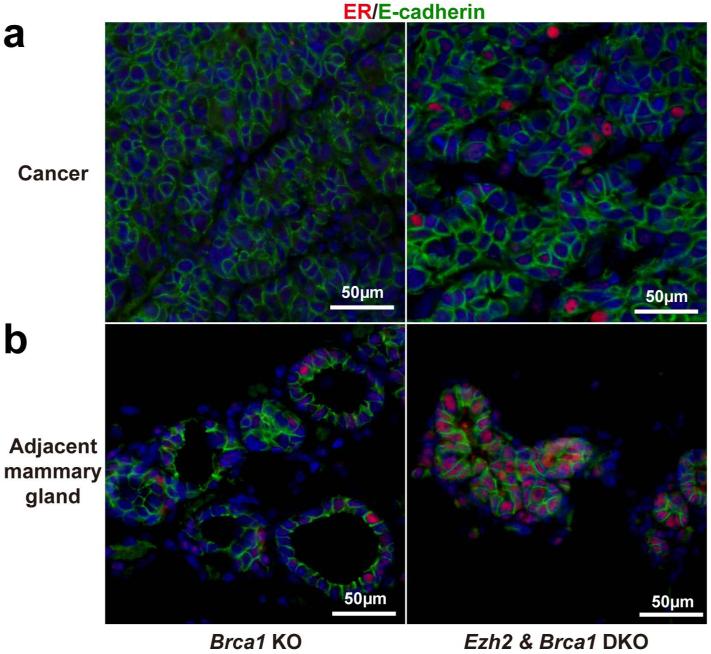

The human data in this study suggested that EZH2 might not be a mandatory methyltransferase for H3K27me3 marks in mammary gland cancers. To test if EZH2 was mandatory for basal mammary cancer development and/or required for H3K27me3 marks, Ezh2 was deleted in the well-characterized mammary-specific Brca1-deficient mouse model that develops basal-type mammary cancers [18]. This model appeared appropriate since human basal-type breast cancer stem cells are reported to express EZH2 [20]. These mice also carry one inactive Trp53 allele. Mammary adenocarcinoma developed at 32 weeks of age in the setting of Brca1 deficiency/Trp53 haploinsufficiency (Figure 3A) and 21 weeks in the setting of Brca1 deficiency/Trp53 haploinsufficiency/EZH2 deficiency (Figure 4A). In Brca1 deficient/Trp53 haploinsufficient mice strong nuclear staining of EZH2 was detected in the cancer tissue but not in adjacent normal epithelium, while the intensity of H3K27me3 staining in cancer tissue and adjacent epithelium was equivalent (Figure 3A and B). In contrast no EZH2 staining was seen in either cancer or normal mammary tissue from the Brca1 deficient/Trp53 haploinsufficient/EZH2 deficient mouse but H3K27me3 staining was maintained in both cancers and normal mammary epithelium (Figure 4A and B). To test if loss of EZH2 modified the basal cancer phenotype in these mice, ER status was evaluated. Interestingly, ER levels were elevated in the cancer that developed in the Brca1 deficient/Trp53 haploinsufficient/EZH2 deficient mouse providing preliminary evidence that EZH2 may have an influence on mammary cancer subtype development (Figure 5A and B).

Figure 3.

Mammary epithelium-specific Brca1 inhibition (Ezh2+/+Brca1f/f;MMTV-CreADp53+/−) induced mammary tumors in mice at 32 weeks. Representative photographs depict H&E (×400) staining and EZH2 and H3K27m3 immunofluorescence of cancer tissue (×800) (row A), and adjacent mammary tissue (×800) (row B).

Figure 4.

Mammary-specific loss of Ezh2 and Brca1 (Ezh2f/fBrca1f/f;MMTV-CreAp53+/−) in mice induced multiple different tumors at 21 weeks. Representative photographs depict H&E (X400) staining and EZH2 and H3K27m3 immunofluorescence of cancer tissue (X800) (row A) and adjacent mammary tissue (X800) (row B).

Figure 5.

Mammary-specific loss of Ezh2 and Brca1 (DKO, Ezh2f/fBrca1f/f;MMTV-CreAp53+/−) in mice induced higher expression of ER compared to Brca1 inhibition in the presence of intact EZH2 (Brca1 KO, Ezh2+/+Brca1f/f;MMTV-CreAp53+/−). Representative photographs depict ER immunofluorescence of cancer tissue (X400) (row A) and adjacent mammary tissue (X400) (row B).

DISCUSSION

The present study identifies low H3K27me3 and high EZH2 as a prognostic factor for shorter OS for breast cancer, including the ER+ breast cancer subtype. These results expand on previously published observations [21] suggesting that low H3K27me3 and high EZH2 levels are predictive of poor prognosis even in ER+ breast cancer. All of the ER+ breast cancer patients in this study were reported to receive anti-hormonal therapy. Previous publications report that high EZH2 expression is part of a gene signature predictive of tamoxifen resistance [22,23] while low EZH2 expression levels correlate with good tamoxifen response [24,25]. The results reported here extend these findings with the suggestion that in the presence of high H3K27me3 patients with high EZH2 levels may, nevertheless, have a favorable prognosis.

Increased EZH2 concentrations have been detected in precancerous cells in morphologically normal breast epithelium, suggesting that an increase in EZH2 expression is a possible early event in breast cancer development [26,27]. In vitro overexpression of EZH2 in immortalized human mammary epithelial cell lines promotes anchorage-independent growth and cell invasion [6] and in vivo EZH2 overexpression in mammary epithelium in genetically engineered mice leads to intraductal epithelial hyperplasia although cancers were not seen [16]. These experiments suggest that EZH2 can modulate cancer cell behavior even if it is not a primary driver of cancer development. The studies reported here demonstrated that EZH2 is not required for mammary cancer development. Because the EZH2-deficient cancers still showed high levels of H3K27me3, the role of this histone modification in mammary cancer development and the enzyme that catalyzes it still needs to be independently studied.

Inactivating mutations in the Ezh2 gene have been identified in patients with myeloid disorders and deletion of Ezh2 in mice is sufficient to induce myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) and myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) like diseases [28]. Aberrant expression patterns of EZH2 have been reported in oral squamous cell carcinoma [29] and high levels are reported in breast cancer stem cells [30]. Further work will be required to determine the mechanism of EXH2 over-expression in breast cancer and its downstream outcomes. As shown here and reported elsewhere, high levels of EZH2 do not always correlate with high levels of H3K27me3 It is possible that the functionality of the highly expressed EZH2 is compromised. One next step would be to sequence and compare the EZH2 genes in the breast cancers with and without low H3K27me3.

Aberrations in the regulation of histone methylation have been reported in human cancers due to mutation of both H3.3 and EZH2. Somatic mutations in H3.3 are reported in pediatric gliomas [31-34] and EZH2 in MDSs and MDS/MPNs [35]. Loss of H3K27me3 has been reported in association with expression of histone H3.1 or H3.3 K27M mutant proteins [33]. Further study into the mutation status of histone genes in breast cancer may be warranted.

High levels of H3K27me3 are linked to more malignant behavior and worse prognosis in patients with prostate [36], esophageal [37], nasopharyngeal [38] and hepatocellular carcinomas [39] but better prognosis in patients with breast, ovarian and pancreatic [21] and non-small cell lung cancers [24]. Here, we have observed that a higher level of H3K27me3 was associated with longer survival in breast cancer, as evidenced by univariate and multivariate analyses consistent with previously reported findings [21].

UTX is a histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase and inactivating mutations are found in multiple cancer types including breast cancer [16]. Wang et al [40] have reported that retinoblastoma pathway gene expression is correlated with UTX expression levels, and low UTX expression is a significant predictor of patient death. Similarly, here we found that high levels of UTX were associated with better overall survival. The fact that high levels of UTX expression were correlated with a high, rather than low, status of H3K27me3 points suggests that high expression of UTX is not the mechanism responsible for the low levels of H3K27me3, at least in this cohort.

A limitation of this study was the relatively small dataset and the use of TMAs to represent whole cancers. This caveat is especially pertinent to the assessment of heterogeneously expressed proteins. Additional prospective studies will be required to validate the prognostic significance of the factors described here. Laboratory and clinical studies will be required to elucidate the mechanism(s) responsible for the poor outcomes correlated with specific expression patterns. A third limitation is that a proliferation marker was not included for evaluation of prognosis. Inclusion of a marker may have provided additional insight into possible mechanisms. A fourth consideration was the choice of the Brca1-deficient mouse model in light of a previous report that BRCA1 reduction elevates H3K27me3 levels at PRC2 target loci through EZH2 re-targeting [41]. These investigators had observed increased migration and invasion of the MDA-MB-221 cell line upon depletion of BRCA1 using siRNA, which was reversed upon Ezh2 knock-down. In mice, loss of Ezh2 in Brca1 tumors did not result in a reduced tumor burden, and possibly even a shortened latency, pointing out differences between in vitro and in vivo experimental systems. This study provides further insight into the regulation of H3K27me3 in the absence of full-length BRCA1 as this mechanism would theoretically not be operative in mice lacking EZH2, yet significant expression of H3K27me3 was found.

In conclusion, this study indicated that the degree of H3K27me3 and EZH2 levels could be used as a prognostic marker in ER+ cancers and demonstrated that EZH2 is not the mandatory methyltransferase that establishes H3K27me3 marks in Brca1-deficient cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (WKB), the IRP of NIDDK and NCI, NIH Grant 5P30CA051008 (PAF).

Definitions for all abbreviations

- EZH2

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2

- H3K27me3

Histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation

- H3K4me3

Histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation

- ER+

Estrogen receptor-positive

- IDC

Invasive ductal carcinoma

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- TMA

Tissue Microarray

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- OS

Overall survival

- MDS

Myelodysplastic syndrome

- MPN

Myeloproliferative neoplasm

- UTX

Ubiquitously Transcribed Tetratricopeptide Repeat Gene on X Chromosome.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W. B. designed the human study and analyzed clinical samples. K.Y. designed and conducted the mouse study. J.L., Y.K. analyzed clinical samples. I.C., M.P., and J.Y. provided clinical samples and data. P.A.F. and L.H. provided the general concept and contributed to interpretation of results and manuscript writing and editing. All authors contributed to the final version.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ko SS. Chronological changing patterns of clinical characteristics of Korean breast cancer patients during 10 years (1996-2006) using nationwide breast cancer registration on-line program: biannual update. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98(5):318–323. doi: 10.1002/jso.21110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan SN, Jankowska AM, Mahfouz R, et al. Multiple mechanisms deregulate EZH2 and histone H3 lysine 27 epigenetic changes in myeloid malignancies. Leukemia. 2013;27(6):1301–1309. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piunti A, Pasini D. Epigenetic factors in cancer development: polycomb group proteins. Future Oncol. 2011;7(1):57–75. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laible G, Wolf A, Dorn R, et al. Mammalian homologues of the Polycomb-group gene Enhancer of zeste mediate gene silencing in Drosophila heterochromatin and at S. cerevisiae telomeres. EMBO J. 1997;16(11):3219–3232. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sauvageau M, Sauvageau G. Polycomb group proteins: multi-faceted regulators of somatic stem cells and cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(3):299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleer CG, Cao Q, Varambally S, et al. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(20):11606–11611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1933744100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez ME, Moore HM, Li X, et al. EZH2 expands breast stem cells through activation of NOTCH1 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(8):3098–3103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308953111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granit RZ, Gabai Y, Hadar T, et al. EZH2 promotes a bi-lineage identity in basal-like breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2013;32(33):3886–3895. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon C, Chagraoui J, Krosl J, et al. A key role for EZH2 and associated genes in mouse and human adult T-cell acute leukemia. Genes Dev. 2012;26(7):651–656. doi: 10.1101/gad.186411.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muto T, Sashida G, Oshima M, et al. Concurrent loss of Ezh2 and Tet2 cooperates in the pathogenesis of myelodysplastic disorders. J Exp Med. 2013;210(12):2627–2639. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yap DB, Chu J, Berg T, et al. Somatic mutations at EZH2 Y641 act dominantly through a mechanism of selectively altered PRC2 catalytic activity, to increase H3K27 trimethylation. Blood. 2011;117(8):2451–2459. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-321208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holm K, Grabau D, Lovgren K, et al. Global H3K27 trimethylation and EZH2 abundance in breast tumor subtypes. Mol Oncol. 2012;6(5):494–506. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee MG, Villa R, Trojer P, et al. Demethylation of H3K27 regulates polycomb recruitment and H2A ubiquitination. Science. 2007;318(5849):447–450. doi: 10.1126/science.1149042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Issaeva I, Zonis Y, Rozovskaia T, et al. Knockdown of ALR (MLL2) reveals ALR target genes and leads to alterations in cell adhesion and growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(5):1889–1903. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01506-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128(4):693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Haaften G, Dalgliesh GL, Davies H, et al. Somatic mutations of the histone H3K27 demethylase gene UTX in human cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41(5):521–523. doi: 10.1038/ng.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elsheikh SE, Green AR, Rakha EA, et al. Global histone modifications in breast cancer correlate with tumor phenotypes, prognostic factors, and patient outcome. Cancer Res. 2009;69(9):3802–3809. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu X, Wagner KU, Larson D, et al. Conditional mutation of Brca1 in mammary epithelial cells results in blunted ductal morphogenesis and tumour formation. Nat Genet. 1999;22(1):37–43. doi: 10.1038/8743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pharoah PD, Caldas C. Genetics: How to validate a breast cancer prognostic signature. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(11):615–616. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herschkowitz JI, Simin K, Weigman VJ, et al. Identification of conserved gene expression features between murine mammary carcinoma models and human breast tumors. Genome Biol. 2007;8(5):R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei Y, Xia W, Zhang Z, et al. Loss of trimethylation at lysine 27 of histone H3 is a predictor of poor outcome in breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers. Mol Carcinog. 2008;47(9):701–706. doi: 10.1002/mc.20413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai L, Rothbart SB, Lu R, et al. An H3K36 methylation-engaging Tudor motif of polycomb-like proteins mediates PRC2 complex targeting. Mol Cell. 2013;49(3):571–582. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi J, Wang E, Zuber J, et al. The Polycomb complex PRC2 supports aberrant self-renewal in a mouse model of MLL-AF9;Nras(G12D) acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2013;32(7):930–938. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Song N, Matsumoto K, et al. High expression of trimethylated histone H3 at lysine 27 predicts better prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Oncol. 2013;43(5):1467–1480. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bultman SJ, Herschkowitz JI, Godfrey V, et al. Characterization of mammary tumors from Brg1 heterozygous mice. Oncogene. 2008;27(4):460–468. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burkart MF, Wren JD, Herschkowitz JI, Perou CM, Garner HR. Clustering microarray-derived gene lists through implicit literature relationships. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(15):1995–2003. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, Gonzalez ME, Toy K, Filzen T, Merajver SD, Kleer CG. Targeted overexpression of EZH2 in the mammary gland disrupts ductal morphogenesis and causes epithelial hyperplasia. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(3):1246–1254. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ernst T, Chase AJ, Score J, et al. Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders. Nat Genet. 2010;42(8):722–726. doi: 10.1038/ng.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adler RH, Herschkowitz N, Minder CE. Homeopathic treatment of children with attention deficit disorder: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166(5):509. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0262-5. H. Frei R. Everts, K.v. Ammon et al. Eur J Pediatr. 2005; 164: 758-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Vlerken LE, Kiefer CM, Morehouse C, et al. EZH2 is required for breast and pancreatic cancer stem cell maintenance and can be used as a functional cancer stem cell reporter. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2(1):43–52. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartzentruber J, Korshunov A, Liu XY, et al. Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature. 2012;482(7384):226–231. doi: 10.1038/nature10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(4):425–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan KM, Fang D, Gan H, et al. The histone H3.3K27M mutation in pediatric glioma reprograms H3K27 methylation and gene expression. Genes Dev. 2013;27(9):985–990. doi: 10.1101/gad.217778.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis PW, Muller MM, Koletsky MS, et al. Inhibition of PRC2 activity by a gain-of-function H3 mutation found in pediatric glioblastoma. Science. 2013;340(6134):857–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1232245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tefferi A. Primary myelofibrosis: 2013 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(2):141–150. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellinger J, Kahl P, von der Gathen J, et al. Global histone H3K27 methylation levels are different in localized and metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Invest. 2012;30(2):92–97. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2011.636117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tzao C, Tung HJ, Jin JS, et al. Prognostic significance of global histone modifications in resected squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Mod Pathol. 2009;22(2):252–260. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai MY, Tong ZT, Zhu W, et al. H3K27me3 protein is a promising predictive biomarker of patients’ survival and chemoradioresistance in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol Med. 2011;17(11-12):1137–1145. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai MY, Hou JH, Rao HL, et al. High expression of H3K27me3 in human hepatocellular carcinomas correlates closely with vascular invasion and predicts worse prognosis in patients. Mol Med. 2011;17(1-2):12–20. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang JK, Tsai MC, Poulin G, et al. The histone demethylase UTX enables RB-dependent cell fate control. Genes Dev. 2010;24(4):327–332. doi: 10.1101/gad.1882610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L, Zeng X, Chen S, et al. BRCA1 is a negative modulator of the PRC2 complex. EMBO J. 2013;32(11):1584–1597. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.