Abstract

PURPOSE

Encouraging dog walking may increase physical activity in dog owners. This cluster randomized controlled trial investigated whether a social networking website (Meetup™) could be used to deliver a multi-component dog walking intervention to increase physical activity.

METHODS

Sedentary dog owners (n=102) participated. Eight neighborhoods were randomly assigned to the Meetup condition (Meetup) or a condition where participants received monthly emails with content from the American Heart Association on increasing physical activity (AHA). The Meetup intervention was delivered over 6 months and consisted of newsletters, dog walks, community events and an activity monitor. The primary outcome was steps; secondary outcomes included social support for walking, sense of community, perceived dog walking outcomes, barriers to dog walking and feasibility of the intervention.

RESULTS

Mixed model analyses examined change from baseline to post-intervention (6 months) and whether change in outcomes differed by condition. Daily steps increased over time (p=0.04, d=0.28), with no differences by condition. The time x condition interaction was significant for the perceived outcomes of dog walking (p=0.04, d=0.40), such that the Meetup condition reported an increase in the perceived positive outcomes of dog walking, whereas the AHA condition did not. Social support, sense of community and dog walking barriers did not significantly change. Meetup logins averaged 58.38 per week (SD=11.62). Within two months of the intervention ending, organization of the Meetup groups transitioned from study staff to Meetup members.

CONCLUSION

Results suggest that a Meetup group is feasible for increasing physical activity in dog owners. Further research is needed to understand how to increase participation in the Meetup group and facilitate greater connection among dog owners.

Keywords: Meetup, exercise, physical activity, cluster randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Despite the health benefits of physical activity, less than 50% of US adults engage in the American College of Sports Medicine/Center for Disease Control’s (ACSM/CDC) recommended 150 minutes of physical activity per week (24). Walking is an excellent way to increase activity as it is inexpensive, accessible and has a low injury risk. Public health initiatives like the Surgeon General’s Everybody Walk initiative have prioritized walking (35). Yet, nearly 40% of adults report no engagement in regular walking for physical activity (6).

Owning a dog may promote physical activity via dog walking (3). Dog owners report more physical activity than non-dog owners.(4,23,10,32,25,9,16,14) Despite this advantage, 59% of dog owners report no dog walking (3). Since 40% of households own a dog,(17) interventions that increase dog walking could potentially increase population-level physical activity.

Few interventions have examined the use of dog ownership to promote physical activity. The only RCT that intervened on dog walking provided written information on canine health and a calendar to record walks. Dog walking increased, though not significantly more than participants who were asked to maintain their current dog walking (27). Kushner(19) tested whether a combined dog and owner weight loss intervention stimulated weight loss. The dog and owner intervention consisted of groups where participants received a weight loss intervention and dog walking strategies. This intervention was compared to a condition that consisted of non-dog owners who received the weight loss intervention. Participants significantly increased their physical activity, with no differences between conditions (19).

Dog walking interventions may benefit from expanding the focus on individual level factors. Interventions guided by a socio-ecological framework could address environmental factors,(18,28,29) such as the context in which individuals live and factors relevant to increasing physical activity in dog owners (e.g., dog friendly spaces, social support for dog walking). We aimed to test whether an online social network used to deliver a multicomponent dog walking intervention could increase physical activity in dog owners.

Online social networks like Facebook™ are increasingly popular platforms for intervening on physical activity because they can create supportive networks for disseminating interventions. Two RCTs used Facebook to increase physical activity in female college students (5) and young adult cancer survivors (36). In both studies, a moderator facilitated Facebook discussions and provided physical activity information. In Cavallo’s(5) study of college students, physical activity increased in participants randomized to the Facebook intervention, but not significantly more than participants who only received education on increasing physical activity. Young adult cancer survivors also increased their physical activity regardless of whether they received the moderator-led or the self-help Facebook intervention.(36) Engagement and acceptability of the Facebook interventions were high, which suggests that online social networks are feasible platforms for promoting physical activity.

While the Facebook interventions attempted to encourage use of the online social network to facilitate online social support for physical activity, no specific attempt was made to connect participants in the “real world” to provide offline (i.e., in person) support. For participants with little offline social support, increases in online social support may not be sufficient to increase physical activity. Meetup™ is an online social network that is structured around scheduling community events to connect members around a specific interest. This unique feature of Meetup may result in greater social support and an enhanced sense of community.

This cluster randomized controlled trial examined the feasibility and initial efficacy of a multi-component dog walking intervention delivered using a Meetup group, compared to a control condition that received monthly emails highlighting content from the American Heart Association’s physical activity website (AHA). Outcomes included daily steps, social support for physical activity, a sense of community and dog walking barriers and perceived outcomes. We hypothesized that participants in the Meetup intervention would significantly improve their daily steps, social support for walking, sense of community, dog walking barriers and positive perceived outcomes from dog walking, compared to participants in the AHA condition. The Meetup intervention feasibility was assessed by evaluating intervention receipt and satisfaction, adverse events and sustainability of the Meetup.

Methods

Design and Randomization

This cluster RCT randomized 8 neighborhoods to the Meetup condition or AHA condition. The 8 neighborhoods were divided based on geographical markers (e.g., highways, city planning designations) and the socio-economic distribution of the cities to ensure that median income would be consistent across conditions. Randomization was stratified by city and median income. An investigator created a random number generator, which was used by the project director to allocate neighborhoods to conditions. Recruitment then occurred in these neighborhoods.

Participants

Residents of Worcester and Lowell, MA were eligible if they owned a healthy dog that was considered a pet, were ≥ 21 years old and had home internet access. Participants with chronic health conditions were eligible with permission from their physician. Exclusion criteria included inability or unwillingness to give informed consent, plans to move out of the area during the study time period, participation in a focus group on the Meetup intervention development, another household member participating in the study, pregnant or planned pregnancy in the next 6 months, a condition that inhibits exercise, self-reported exercise of more than 150 minutes per week, activity monitor measured steps greater than 56,000 steps per week (i.e., 8000 per day), owning a dog with a history of biting humans, a dog that had not received a rabies vaccine or a dog that was incapable of walking a ¼ mile.

Procedures

Participants were recruited from January to May 2012 via flyers sent to registered dog owners in Worcester and Lowell, flyers posted in veterinary clinics, pet stores and other community locations, Craigslist advertisements and advertisements in local newspapers. Students and employees of the University of Massachusetts were recruited through ads posted on the intranet, in emailed newsletters and on bulletin boards within the institution. Interested individuals called to learn about the study and complete an initial eligibility screening. Interested individuals provided their home address so that the research assistant could determine if they resided in an included neighborhood. Those who met initial eligibility received information on the study. Potentially eligible participants were scheduled for a 30-minute in-person screening where they provided written informed consent and their dog’s rabies vaccination paperwork, completed a medical history form and a physical activity questionnaire, and received an activity monitor to wear for 7 days. Participants with chronic health conditions also had a form faxed to their physician for permission to participate. After 7 days, participants returned for a 60-minute baseline visit to download their steps; those with <8000 steps/day were eligible and completed baseline questionnaires. Participants from neighborhoods randomized to the Meetup condition also received an orientation to the Meetup website. Participants received $25 (cash or gift card) for completing baseline procedures. The University of Massachusetts Medical School and the University of Massachusetts Lowell Internal Review Boards approved this study, and a Data Safety and Monitoring Board met biannually to review the trial.

Intervention development

The intervention was developed by the investigators and reviewed by two community advisory boards consisting of dog owners and community partners from each city. Nine focus groups with dog owners from each city were also conducted to inform the intervention. Common suggestions were identified, integrated into the intervention and reviewed by the investigative team and community advisory boards. Suggestions included: 1) an introductory meeting for dog owners to meet one another and establish guidelines, 2) specific newsletter content (e.g., ask the veterinarian, information on free/reduced veterinarian services and dog friendly-establishments and highlighting adoptable dogs, 3) allowing steps to be tracked steps on the Meetup website and 4) providing incentives for tracking steps.

Meetup condition

Participants in the Meetup condition participated in a 6 month, online social network focused on increasing dog walking. The intervention was delivered via a Meetup group, which is a freely available online social network. Meetup includes a message board where members can post comments and questions. Two Meetup groups were created, one in each city. After the baseline assessment, participants received an email with the link to the Meetup group to sign up. Participants who did not sign up received reminder emails. Research staff monitored Meetup content. The intervention began in May for Worcester and June, 2012 for Lowell, due to recruitment challenges. There were 5 intervention components.

1. Introductory meeting

Meetup participants were invited to participate in a one-hour meeting where they could meet dog owners and establish guidelines for using Meetup and participating in the neighborhood walks.

2. Neighborhood walks

Walks were posted on Meetup and led by a staff member. Walks were initially scheduled every other week, but increased after 2 months to weekly in Worcester and three times/month in Lowell per participant requests. Walks occurred in different locations within the Meetup neighborhoods and on different days (weekdays and weekends) and times (late morning, late afternoon, and early evening) to accommodate participant preferences for walk days and times. Walk length typically ranged between 1–2 miles.

3. Community events

Three community events that were dog friendly and involved physical activity (e.g., charity run/walk) were promoted on Meetup. The study sponsored a booth to promote dog walking and the Meetup group, and to provide an opportunity for dog owners to meet with the study’s animal behavior expert to address dog behavior issues.

4. Newsletters

Newsletters were posted weekly on Meetup to encourage participants to access the website. Newsletter content was based on social-cognitive theory and included information on the benefits of dog walking and dog health, strategies for increasing and maintaining dog walking, relapse prevention, dog training tips, descriptions of places to walk dogs and dog related-resources (e.g., discounts for dog services).

5. Activity monitor

Participants received an activity monitor to track walking goals. They could log their steps daily via a website linked to the Meetup. Each month, participants with the three highest monthly step counts received a gift card ($10, $15 or $25).

AHA condition

Participants in neighborhoods randomized to the AHA condition received 6 monthly emails with encouragement to begin walking and a link from the AHA website for starting a physical activity program.(1) Each month a different section of the website was highlighted (e.g., The Price of Inactivity, Get Moving!). Emails were sent over the same 6-month period as the intervention to control for seasonal variation in physical activity.

Post-intervention assessment

After 6 months, participants wore the activity monitor for 7 days and completed a one-hour assessment visit to complete questionnaires and download their steps. They received $25 (cash or gift card) for completing the assessment.

Measures

Screening measures

Age, gender, race/ethnicity and education were self-reported. Body weight and height was measured using a balance beam or digital scale with the participant wearing only light clothing and no shoes and used to calculate BMI. Participants completed a brief medical history questionnaire and the Revised Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (rPAR-Q)(34) as assurance that they were safe to increase their walking. Participants completed the reliable and valid Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale(7) to capture environmental aspects related to walking, for use as a possible covariate in analyses.

Steps

Participants were instructed to wear an activity monitor (New Lifestyles NL-800) for 7 days, at least 10 hours/day at baseline and 6-months. A different version of NL-800, the NL-2000, which uses the same piezoelectric pedometer mechanism to measure steps, demonstrated strong reliability and validity in adults, in laboratory and non-laboratory settings. (11,12,21,31,33) Participants received verbal and written instructions on the placement of the activity monitor and situations in which it should not be worn (e.g., swimming, sleeping). The activity monitor has a memory chip that stored the number of steps walked. After 7 days, participants returned to the lab and their steps were recorded. Only days with ≥ 100 steps were considered valid and used to calculate average steps/day (2). Only 0.012% of the steps/day were deemed invalid. Except for one participant who only had 3 days, participants had at least 4 days of valid and non-missing data.

Dogs and Physical Activity Tool(13)

This validated measure assesses minutes individuals spend walking their dog in a typical week, dog walking barriers (e.g., weather) and perceived outcomes from dog walking (e.g., help me relax). The 17-item barriers subscale and the 12-item perceived outcomes subscale are rated on a 7-point scale (1=very unlikely to 7=very likely). Higher scores indicate greater barriers and more positive perceived outcomes. Internal consistency was α=0.81 for the barriers subscale and α=0.73 for the perceived outcomes subscale. Weekly dog walking minutes was omitted from analyses due to validity concerns. Weekly dog walking minutes was not correlated with weekly steps at baseline (r=0.05, p=0.64 or 6 months (r=0.10; p=0.40), 17% of participants did not provide a total at baseline and 34.9% of participants may have misinterpreted the question as they reported between 1 and 3.5 minutes per week.

Social Support for Walking

This valid and reliable 26-item measure has participants rate whether friends/family support their exercise behavior using a 1–5 scale (1=none and 5=very often) (30). The measure asked specifically about walking. Internal consistency for the family and friend participation subscales was α=0.91 and α=0.92, respectively. The rewards and punishment subscale demonstrated poor internal consistency (α=0.30), so this subscale was omitted from analyses.

Sense of Community Index

This 24-item valid and reliable scale assesses community membership, influence, whether or not one’s needs are being met and presence of a shared emotional connection within one’s community (8). Items are rated on a 4-point scale where 0=not at all and 3=completely; α= 0.94.

Feasibility

Intervention receipt was assessed via Meetup logins, which were tracked using Google analytics (staff logins were subtracted from total logins). Participants also self-reported their use of intervention components (e.g., newsletters). Participants reported their intervention satisfaction by rating the Meetup components on a scale, where 1=very dissatisfied and 5=very satisfied. Adverse events were tracked and rated as being possibly related to study participation or unrelated. Contamination was examined by having participants in the AHA condition complete a questionnaire inquiring about whether they knew anyone in the Meetup group and their participation at community events and neighborhood dog walks. Sustainability was assessed two months after the intervention ended by examining Meetup membership and frequency of neighborhood walks. After the intervention ended, the Meetup group was opened to all participants and community members to assess the extent to which the Meetup group could be sustained. Two months following intervention completion, Meetup organization was transitioned from staff to Meetup members who agreed to be a co-organizer.

Sample size

Sample size was determined for change in steps, compared between conditions. To demonstrate a difference of 400 steps/day, 31 participants/condition would yield 80% power, assuming a two-sided test and α=0.05. Adjusting for 20% loss to follow-up requires 39 participants/condition. The design effect (DEFF) was calculated to account for clustering. Assuming an average cluster size of 10 participants (and 4 clusters/city) and a reasonably low intraclass correlation (i.e., 0.05), the DEFF = 1+0.05(10-1) = 1.45. Sixty participants per condition (N=120) would provide 80% power to detect differences in the 400 step range.

Analytic plan

Data were plotted using histograms and skewness was formally assessed to ensure that data were normally distributed and met assumptions required for analysis. Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe the sample.

Intent-to-treat analyses were completed; all participants were included in the analysis in their assigned condition. Missing data at the 6-month assessment remained coded as missing. Mixed models were conducted to estimate the effect of the Meetup condition on the outcomes over time using maximum likelihood and an identity covariance structure. Models included time, condition and the time by condition interaction. An indicator for neighborhood was included in the models by nesting neighborhood within the condition variable, as neighborhood was the unit of randomization (i.e., clustering factor). Models included a random intercept and were adjusted to account for repeated observations of participants over time.

T-tests and chi-square analyses were used to compare conditions on variables associated with physical activity (e.g., age, BMI, neighborhood walkability, gender and race/ethnicity) for possible inclusion as covariates. Since the recruitment timeframe spanned a change in seasons (January to May) and weather can impact physical activity, chi-square was also used to compare conditions on the month of the baseline assessment. Mixed models were also run adjusting for covariates to ensure that results were consistent with unadjusted models.

Descriptive statistics were conducted for the feasibility analyses. An alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. SPSS (Version 20.0; IBM Corporation) was used for data analysis.

Results

Enrollment and retention

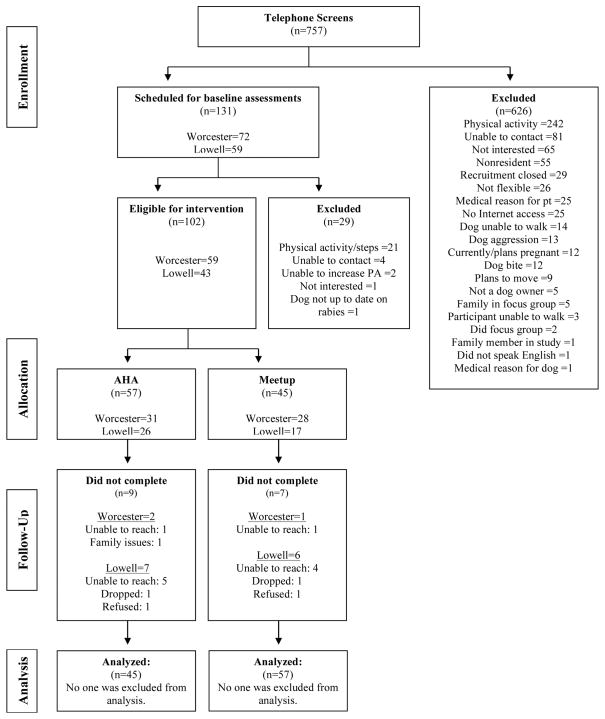

See Figure 1 for a diagram of participant enrollment and retention. Of the 757 individuals who inquired about the study, 131 (17.31%) met initial telephone eligibility criteria. Of those scheduled for a baseline, 102 (78.86%) completed the visit and were enrolled. At the 6-month follow-up, 86 participants (84.31%) provided data on the primary outcome.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study phases.

Participants

Participant demographics, stratified by condition, are reported in Table 1. Participants were mostly female (76.47%) and non-Hispanic white (84.31%), with 65.69% who had a college degree or higher. At baseline, participants in the Meetup condition walked significantly more [Msteps/day=5436.72; SD=1408.96] compared to participants in the AHA condition [Msteps/day=4478.63; SD=1500.36] (t=3.29, p=0.001). Baseline steps were normally distributed such that skewness and kurtosis were less than 1. The conditions also differed at baseline on two walkability subscales: neighborhood aesthetics (t=2.203, p=0.046) and neighborhood crime (t=2.996; p=0.003), with participants in the Meetup condition reported greater aesthetics and less crime than participants in the AHA condition. The month during which participants completed their baseline also differed by condition with participants in the AHA condition more likely to complete their baselines early in the recruitment timeframe (i.e., January) compared to Meetup participants (Χ2=16.26, p=0.006). Adjusted models controlled for neighborhood aesthetics, neighborhood crime and month of baseline assessment.

Table 1.

Baseline participant description, by study condition (N=102).

| Meetup (n =45) | AHA (n =57) | |

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Age: | 49.20(13.72) | 47.49 (12.26) |

| BMI | 30.56(5.37) | 31.18 (7.32) |

| Baseline average steps per day | 5436.72 (1408.96) | 4478.63 (1500.36)* |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity: | ||

| Non-Hispanic, White | 40 (88.90%) | 46 (80.70%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (4.44%) | 4 (7.02%) |

| Other | 1 (2.22%) | 6 (10.53%) |

| Unknown | 2 (4.44%) | 1 (1.75%) |

| Gender: | ||

| Female | 34 (75.6%) | 44 (77.2%) |

| Male | 11 (24.4%) | 13 (22.8%) |

| Marital Status: | ||

| Married/Living with partner | 27 (60%) | 39 (68.4%) |

| Single | 10 (22.2%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 7 (15.5%) | 12 (21.1%) |

| Unknown | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (1.8%) |

| Highest Education Level Achieved: | ||

| Less than a Bachelors degree | 14 (31.11%) | 21 (36.84%) |

| Bachelors degree | 10 (22.22%) | 14 (24.56%) |

| Greater than a Bachelors degree | 20 (44.44%) | 21 (36.84%) |

| Unknown | 1 (2.22%) | 1 (1.75%) |

Primary and secondary outcomes

Steps

Unadjusted analyses indicated a non-significant time x condition interaction for steps (F=1.90, p=0.16), but a significant time main effect (F=4.36, p=0.04, d=0.28), such that daily steps increased from baseline to 6 months (MΔ=651.24; 95% CI: 32.43 – 1270.06). Although the time x condition interaction was not significant, the effect size for the interaction (d=0.28) was comparable to the time main effect, with average steps/day increasing by 919.46 in the Meetup condition and by 424.70 in the AHA condition. The time main effect was significant in the adjusted model (F=5.95, p=0.02).

Sense of community

Neither the interaction (F=1.55, p=0.22) nor the time main effect of (F=3.68, p=0.06) was significant for sense of community in unadjusted analyses.

Social support

The time main effect and the time x condition interaction were not significant for social support participation from friends (F=0.23, p=0.63 and F=0.99, p=0.38, respectively) or from family (F=0.08, p=0.78 and F=0.31, p=0.73, respectively).

Dogs and physical activity tool

For barriers, no significant condition x time (F=0.69, p=0.51) or time main effect (F=0.30, p=0.59) emerged. A significant condition x time interaction emerged for the perceived behavioral outcomes of dog walking (F=3.45, p=0.04, d=0.40). Simple effects revealed no change for the AHA condition (F=0.40, p=0.54; MΔ=−0.67, 95% CI=−2.80 – 1.47), while Meetup condition participants reported a significant increase in positive behavioral outcomes (F=4.73, p=0.04; MΔ=2.67, 95% CI: 0.17 – 5.18). The interaction was also significant in the adjusted model (F=3.58, p=0.03).

Feasibility

Intervention receipt

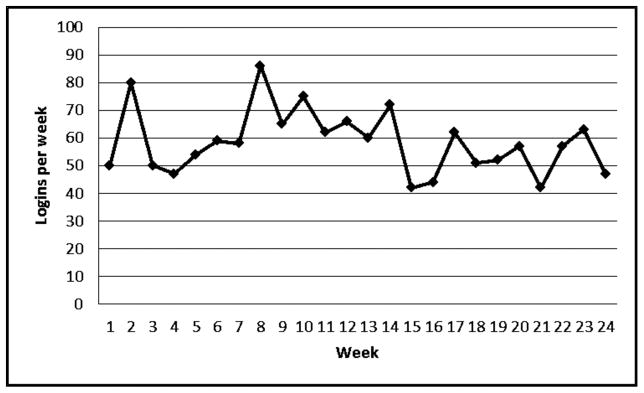

Twelve participants did not sign up for the Meetup. Participants reported not signing up because of: 1) deciding not to continue with the study; 2) laziness/too much work/no time; and 3) computer problems. Figure 2 displays weekly logins to the Meetup groups over the duration of the intervention. Logins averaged 58.38/week (SD=11.62). The majority of participants (55.0%) reported that they did not attend any community events and 42.9% reported that they never commented on the Meetup website. Participants reported attending a range of 0–11 dog walks (M=2.07; SD=3.11). Newsletter reading varied with 7.1% of participants reporting that they did not read any and 28.6% reporting that they read all 24. Activity monitor use also varied with 39.3% of participants reporting that they used it 5 times or less and 35.7% reporting daily or almost daily use; 60.7% of participants reported that they never recorded their steps on the website.

Figure 2.

Meetup logins per week during the intervention (n=45).

Participant satisfaction

Table 2 contains average satisfaction ratings for Meetup components. Satisfaction ratings ranged from a low of 2.97 (SD=1.27) for the schedule of neighborhood walks to 4.00 (SD=1.26) for the activity monitor. 46.4% of participants reported that none of the dog walks were scheduled at a convenient time.

Table 2.

Satisfaction ratings for the intervention components and each items correlation with change in steps (N=32).

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Correlation r | |

|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied were you with the Meetup website overall? | 3.78 | 1.07 | 0.12 |

| How satisfied were you with the ease of posting comments to the Meetup website? | 3.61 | 1.20 | 0.27 |

| How satisfied were you with the ease of starting a discussion on the Meetup website? | 3.4 | 1.13 | 0.10 |

| How satisfied were you with the Meetup members? | 3.41 | 1.01 | 0.17 |

| How satisfied were you with the participation of the Meetup members? | 3.16 | 1.04 | 0.00 |

| How satisfied were you with the neighborhood walks? | 3.53 | 1.11 | −0.003 |

| How satisfied were you with the location of the neighborhood walks? | 3.56 | 1.22 | −0.03 |

| How satisfied were you with the schedule of neighborhood walks? | 2.97 | 1.26 | 0.08 |

| How satisfied were you with the information provided in the newsletters? | 3.91 | 1.06 | 0.14 |

| How satisfied were you with the community events?a | 3.63 | 1.03 | 0.26 |

| How satisfied were you with the booth the study sponsored at the community?b | 3.31 | 1.03 | 0.55* |

| How satisfied were you with the pedometer provided? | 4.00 | 1.23 | 0.16 |

| How satisfied were you with the walker tracker website for tracking the pedometer? | 3.17 | 0.95 | 0.32 |

| How satisfied are you with the Meetups ability to help you walk your dog more? | 3.50 | 1.19 | 0.45** |

| How satisfied are you with the Meetups ability to help you increase your physical activity? | 3.47 | 1.19 | 0.47** |

| How satisfied are you with the Meetups ability to help you meet other dog owners? | 3.31 | 1.12 | 0.29 |

Only participants who attended a community event rated this item (n=16)

Only participants who attended a community event rated this item (n=13)

p<.05;

p<.01

Adverse events

One person in the Meetup condition died before the intervention began. Nineteen additional adverse events were person-related (5 in the Meetup condition and 14 in the AHA condition); 6, all in the AHA condition, were possibly related to dog walking. Fifteen dog-related adverse events occurred (6 in the Meetup condition and 9 in the AHA condition); 5 were possibly related to dog walking (2 in the Meetup condition)

Contamination

Only 19.6% of AHA participants had heard of Meetup. None of the AHA participants reported that they knew someone who was a member of the dog walking Meetup group, participated in a neighborhood walk or viewed any newsletters.

Sustainability

Following conclusion of the intervention, Meetup groups were opened to the entire community with Meetup members taking over the organizer responsibilities. After six months, membership grew to 110 members in Worcester and 71 in Lowell with dog walks occurring weekly in Worcester and 1–2 times per month in Lowell.

Post-hoc analyses

Given the variability in reported participation in the Meetup, post-hoc analyses were conducted to explore the relationship between change in steps and Meetup components. These analyses only included Meetup participants who completed the 6 month assessment (n=34; with the small sample size, a correction was not applied). Participants who did not sign up for the Meetup reported an average decrease in daily steps of 767.13 (SD=2106.86), while participants who did sign up reported an average increase of 1256.17 daily steps (SD=3905.49) (t=1.79, p=0.09). Correlations between change in daily steps and intervention components were only significant for activity monitor use (r=0.49, p=0.003). The correlations between change in daily steps and satisfaction are included in Table 2. Moderate associations were observed for change in daily steps and satisfaction with the Meetup’s ability to help participants walk their dog more (r=0.45, p=0.009) and help them increase their physical activity (r=0.47, p=0.007).

Discussion

This study examined whether a dog walking intervention delivered via a social networking website could increase physical activity more than material from the American Heart Association’s physical activity website. Participants significantly increased their daily steps from baseline to six months. While the Meetup condition participants increased their daily steps by 494 more than the AHA condition, the difference between conditions was not significant. However, the effect size for the time x condition interaction was comparable to the main effect of time. Although this difference in steps may seem modest, any increase in physical activity may confer benefits (22). The Meetup condition did not increase participants’ social support for walking, nor their sense of community, but participants in the Meetup intervention reported an increase in the perceived positive outcomes of dog walking compared to the AHA condition.

Results were consistent with the only other randomized trial that examined whether intervening on dog walking increases physical activity (27). Though the lack of a significant difference in steps between conditions could be attributed to low power, the intervention may have been too minimal to significantly increase steps beyond what a physical activity website can accomplish. Participants were not required to engage in any aspects of the intervention, and some participants took more advantage of the components than others. The Meetup groups were also small for a social network (Worcester n=28; Lowell n=17). Larger networks may be required to increase engagement in Meetup groups and ensure that participants feel connected to the social network (26).

Although 27% of participants did not sign up for the Meetup website, those that did, regularly accessed the Meetup website and were mostly satisfied with the features. The lowest satisfaction ratings were for the schedule of neighborhood walks. Participants listed their preferred days and times for walks, which varied from mid-morning to after 6pm during the week and weekend. Walks were scheduled at different times and days to accommodate this variability, which meant that not all participants could attend every walk. Although the scheduling may not have been ideal, participants seemed to enjoy the neighborhood walks as evidenced by the request to increase the frequency of the walks, and the satisfaction rating.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for the feasibility of using an online social network, like Meetup, to connect local dog owners comes from the sustainability data. The membership of the two Meetup groups has grown and neighborhood dog walks have continued, without organizational assistance from research staff. Using an online social network focused on dog walking to increase physical activity did not require the space and expertise of many other formal physical activity programs. Though this informal approach may not have resulted in increases in physical activity comparable to more formal programs, the minimal requirements necessary to sustain the intervention may, in the long run, offer greater benefits, given the challenges of physical activity maintenance (20). Whether the sustainability of the Meetup group enabled participants to maintain their increased physical activity deserves further study.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use Meetup for intervention instead of Facebook, Twitter or another online social network. Meetup may offer certain advantages for interventions that seek to intervene within a specific community. Recruiting members may be easier with a Meetup group as Meetup promotes groups to non-members. That is, if you are a member of a certain Meetup, Meetup will inform you of other Meetup groups in your area that are relevant to your interests. Meetup also includes a formal mechanism for connecting members of the online social network in person to potentially facilitate online and offline connections. Although participants were encouraged to schedule their own dog walks as a way of increasing social contact and physical activity among members, no participants took advantage of this option, until the formal intervention ended and Meetup organization was transferred from research staff to Meetup members. During the initial meeting, we attempted to encourage participants to take ownership of the group by establishing Meetup guidelines. Further research could explore ways to facilitate participant scheduling of events and posting on the Meetup website. Resnick (26) identified providing contests with small prizes as the most effective way to encourage posting in online forums. Alternatively, research could shift to examining how to encourage sedentary dog owners to participate in existing dog-walking Meetups. Dog-related Meetups are quite popular with 784 Meetup groups representing over 102,000 members in 27 countries (15). Strategies for encouraging sedentary dog owners to connect to existing Meetups could include recommendations from veterinarians, connections with pet stores or mass mailings to licensed dog owners.

Although this study provides valuable information about the feasibility of a dog-walking Meetup group to increase physical activity, study limitations require discussion. While the age range of the study was broad (25 to 80 years), the sample was mostly female, white and well-educated, which limits generalizability. The wide age range may have hindered some participants’ interest in the Meetup, as one participant commented on the follow-up survey, “I felt like most of members were a little older than myself …I worry about lack of common interest.” A larger sample may have increased participant diversity and the likelihood that participants have shared interests, other than dog ownership. Whether participants maintained their gains in physical activity is unknown as the study only included a post-intervention assessment. The primary outcome, steps, was measured via an activity monitor. While activity monitors may be more accurate than self-report, they are vulnerable to measurement error.

Using a dog walking Meetup group to increase physical activity in sedentary dog owners is feasible and promotes the perception of positive outcomes from dog walking. Research on strategies for leveraging existing dog-related Meetups to increase physical activity in dog owners may address many of this study’s Meetup limitations and result in greater increases in physical activity in dog owners.

Acknowledgments

Our community partners, Common Pathways and Lowell Unleashed provided valuable input on the conduct of the study. The authors are grateful to Dr. Hayley Christian for giving permission to use her Dogs and Physical Activity tool for the study. We owe tremendous gratitude to the participants for their willingness to participate in this study. The present study’s results do not constitute endorsement by ACSM.

Funding source

This study was funded by a pilot project to Dr. Schneider (5 UL1RR031982-02) from the University of Massachusetts Medical School’s Center for Clinical and Translational Studies, which is funded by the National Institute of Health. The clinical trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (#NCT01593449).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise® Published ahead of Print contains articles in unedited manuscript form that have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication. This manuscript will undergo copyediting, page composition, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered that could affect the content.

References

- 1.American Heart Association. Getting Healthy: Physical Activity. 2013 Web site [Internet]. [cited 2010 August 15]. Available from: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/PhysicalActivity/Physical-Activity_UCM_001080_SubHomePage.jsp.

- 2.Bassett DJ, Wyatt H, Thompson H, Peters J, Hill J. Pedometer-measured physical activity and health behaviors in U.S. adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(10):1819–25. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181dc2e54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauman AE, Russell SJ, Furber SE, Dobson AJ. The epidemiology of dog walking: an unmet need for human and canine health. Med J Aust. 2001;175(11–12):632–4. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown SG, Rhodes RE. Relationships among dog ownership and leisure-time walking in Western Canadian adults. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(2):131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavallo D, Tate D, Ries A, Brown J, Devellis R, Ammerman A. A social media–based physical activity intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5):527–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More people walk to better health. CDC Vital Signs. 2012 [Internet] [cited 2012 August 1]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2012-08-vitalsigns.pdf.

- 7.Cerin E, Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD. Neighborhood environment walkability scale: validity and development of a short form. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(9):1682–91. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000227639.83607.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chavis DM, Lee KS, Acosta JD. The Sense of Community (SCI) Revised: The Reliability and Validity of the SCI-2. International Community Psychology Conference; 2008; Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christian H, Giles-Corti B, Knuiman M. "I'm just walking the dog" correlates of regular dog walking. Fam Community Health. 2010;33(1):44–52. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181c4e208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christian H, Westgarth C, Bauman A, Richards EA, Rhodes R, Evenson KR, et al. Dog ownership and physical activity: a review of the evidence. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10(5):750–9. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.5.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crouter SE, Schneider PL, Bassett DR., Jr Spring-levered versus piezo-electric pedometer accuracy in overweight and obese adults. Medi Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(10):1673–9. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000181677.36658.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crouter SE, Schneider PL, Karabulut M, Bassett DR., Jr Validity of 10 electronic pedometers for measuring steps, distance, and energy cost. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1455–60. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078932.61440.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutt HE, Giles-Corti B, Knuiman MW, Pikora TJ. Physical activity behavior of dog owners: development and reliability of the dogs and physical activity (DAPA) tool. J Phys Act Health. 2008;5 (Suppl 1):S73–89. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.s1.s73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cutt H, Giles-Corti B, Knuiman M, Timperio A, Bull F. Understanding dog owners' increased levels of physical activity: results from RESIDE. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(1):66–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.103499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dogs Meetup Groups. 2013 [Internet]. [cited 2013 November 1]. Available from: http://dogs.meetup.com/

- 16.Hoerster KD, Mayer JA, Sallis JF, Pizzi N, Talley S, Pichon LC, et al. Dog walking: its association with physical activity guideline adherence and its correlates. Prev Med. 2010;10:1016. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Humane Society of the United States. US Pet Ownership Statistics. 2009 [Internet] [cited 2009 May 1]. Available from: http://www.hsus.org/pets/issues_affecting_our_pets/pet_overpopulation_and_ownership_statistics/us_pet_ownership_statistics.html.

- 18.King AC, Satariano WA, Marti J, Zhu W. Multilevel modeling of walking behavior: advances in understanding the interactions of people, place, and time. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(7 Suppl):S584–93. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c66b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kushner RF. Companion dogs as weight loss partners. Obesity Management. 2008;10:232–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcus B, Dubbert P, Forsyth L, McKenzie T, Stone E, Dunn A, et al. Physical activity behavior change: issues in adoption and maintenance. Health Psychology. 2000;19(1 Suppl):32–41. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melanson EL, Knoll JR, Bell ML, Donahoo WT, Hill JO, Nysse LJ, et al. Commercially available pedometers: considerations for accurate step counting. Prev Med. 2004;39:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore S, Patel A, Matthews C, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Park Y, Katki H, et al. Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLOS Medicine. 2012;9(11):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oha K, Shibata A. Dog ownership and health-relted physical activity among Japanese adults. Journ Phys Act and Health. 2009;6:412–8. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prevalence of Regular Physical Activity Among Adults-United States 2001 and 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(46):1209–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reeves MJ, Rafferty AP, Miller CE, Lyon-Callo SK. The impact of dog walking on leisuire-time physical activity: results from a population-based survery of Michigan adults. Journ Phys Act and Health. 2011;8:436–44. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Resnick P, Janney A, Buis L, Richardson C. Adding an online community to an internet-mediated walking program. Part 2: strategies for encouraging community participation. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(4):e72. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhodes R, Murray H, Temple VA, Tuokko H, Higgins JW. Pilot study of a dog walking randomized intervention: effects of a focus on canine exercise. Prev Med. 2012;54:309–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sallis JF, Bauman A, Pratt M. Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15(4):379–97. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson KA, Kraft MK, Kerr J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:297–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med. 1987;16(6):825–36. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider PL, Crouter S, Bassett DR. Pedometer measures of free-living physical activity: comparison of 13 models. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(2):331–5. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000113486.60548.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serpell J. Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behaviour. J R Soc Med. 1991;84(12):717–20. doi: 10.1177/014107689108401208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swartz AM, Bassett DR, Jr, Moore JB, Thompson DL, Strath SJ. Effects of body mass index on the accuracy of an electronic pedometer. Int J Sports Med. 2003;24:588–592. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-43272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the physical activity readiness questionnaire (PAR-Q) Can J Sport Sci. 1992;17(4):338–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Health and Human Services USDoHH. Walking and Walkability. [Internet]. [cited 2013 October 1]Available from: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/initiatives/walking/index.html.

- 36.Valle C, Tate D, Mayer D, Allicock M, Cai J. A randomized trial of a Facebook-based physical activity intervention for young adult cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):355–68. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]