Abstract

Objectives

To assess the overall safety and potential endometrial stimulation of soy isoflavone tablets consumed (3-year) by postmenopausal women. To determine the endometrial thickness response-to-treatment among compliant women, taking into account hormone concentrations and other hypothesized modifying factors.

Methods

We randomized healthy postmenopausal women (45.8–65.0 years) to placebo control or two doses (80 or 120 mg/day) of soy isoflavones at two sites. We used intent-to-treat (N=224) and compliant (>95%; N=208) analyses to assess circulating hormone concentrations, adverse events, and endometrial thickness (via transvaginal ultrasound).

Results

Median values for endometrial thickness (mm) declined from baseline through 36 mo. Nonparametric ANOVA for treatment differences among groups showed no differences in absolute (or percentage change) endometrial thickness at any time point (Chi-Square p-values ranged from 0.12–0.69), nor in circulating hormones at any time point. A greater number of adverse events for the genitourinary system (p=0.005) was noted in the 80 compared to 120 mg/day group, whereas other systems showed no treatment effects. The model predicting the endometrial thickness response-(using natural logarithm)-to-treatment with compliant women across time points was significant (p<0.0001), indicating that estrogen exposure (p=0.0013), plasma 17 β-estradiol (p=0.0086), and alcohol intake (p=0.023) contributed significantly to the response. Neither the 80 (p=0.57) nor 120 (p=0.43) mg/day dose exerted an effect on endometrial thickness across time.

Conclusions

Our RCT verified the long-term overall safety of consuming soy isoflavone tablets by postmenopausal women who displayed excellent compliance. We found no evidence of a treatment effect on endometrial thickness, adverse events, or circulating hormone concentrations, most notably thyroid function, during a three year period.

Keywords: Soy isoflavone supplements, safety, transvaginal ultrasound, 17 β-estradiol, estrone-sulfate, thyroid-stimulating hormone

INTRODUCTION

Soy isoflavone supplements, which have been promoted in the lay press, are very popular as an alternative to hormone therapy for peri- and postmenopausal women. Despite the widespread use of soy isoflavones and published efficacy trials using soy isoflavones for a variety of outcomes, very few studies have reported on adverse events or safety outcomes in midlife women. Yet, it is critical to examine the long-term safety of chronic soy isoflavone exposure in humans, particularly because high doses can be ingested with supplements. Indeed, soy isoflavone tablets easily allow intake in excess of 100 mg isoflavones/d, five times that of isoflavone intake from typical Asian diets1. One long-term (3 y) study2 indicated that soy isoflavone (extract form) intake was safe for the endometrium and breast, another (2 y) study3 demonstrated that soy hypocotyl isoflavones (80 or 120 mg) did not adversely affect endometrial thickness, and another recent (1 y) study4 showed that soy isoflavones (60 mg) combined with Lactobacillus sporogenes was safe for the endometrium, mammary glands, and liver function. Indeed, a 2-y study5 indicated that genistein (54 mg/d), the predominant soybean isoflavone, reduced the mean number of hot flushes/d, but it did not affect the endometrium. Another small randomized crossover design study6 noted that neither a low- nor high-isoflavone diet for 3 mo had a significant effect on either vaginal cytology or endometrial biopsy results. In contrast to these studies, one report7 revealed that long-term (up to 5 y) soy isoflavone treatment (150 mg/d) was associated with increased (3.8%) occurrence of endometrial hyperplasia (five with simple and one with complex hyperplasia) at 60 but not at 30 mo, with no cases of endometrial carcinoma in either group. Although the majority of studies have demonstrated safety, additional long-term studies are needed to corroborate either the stimulatory or non-stimulatory effect of these compounds on the endometrium, as well as to report on adverse events and overall safety-related outcomes. Unique features of the current study were its long duration, realistic daily isoflavone doses, robust sample size, excellent rates of compliance during a 3-year intervention, adverse event monitoring throughout, and longitudinal modeling of the multiple factors hypothesized to modify the endometrial thickness response-to-treatment. The overall objective of this double-blind randomized controlled trial was to determine whether long-term (3 y) intake of soy isoflavone tablets by postmenopausal women was related in general to adverse events, and in particular to hormone concentrations and/or endometrial thickness.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Study design

Participants for the current study were from the parent trial (Soy Isoflavones for Reducing Bone Loss [SIRBL]),8 which had a primary objective to determine the 3-y effect of 2 doses (80 or 120 mg/d) of isoflavones extracted from soybeans on lumbar spine and total proximal femur BMD in at-risk postmenopausal women. The overall objective of the current study was to determine whether there was a treatment effect on circulating hormones, adverse events, and/or endometrial thickness. A secondary objective was to determine the response-to-treatment of endometrial thickness among the compliant women, while taking into account hormone concentrations, as well as other hypothesized factors, that may modify the response-to-treatment or be related to endometrial thickness. These modulating factors included hormones (17 β-estradiol, free estradiol, or bioavailable estradiol; estrone-sulfate; sex hormone-binding globulin [SHBG], thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH]); age or estrogen exposure (EstExp) or time since last menstrual period (TLMP); BMI or whole-body fat mass; alcohol intake, and duration of lactation in relation to pregnancies carried to term. Healthy postmenopausal women aged 45.8–65.0 y were enrolled in this prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter (Iowa State University [ISU], Ames, IA; University of California at Davis [UCD], Davis, CA; University of Minnesota, St Paul, MN [analysis site]), National Institutes of Health–funded clinical trial. We collected data from participants at baseline and at 6, 12, 24, and 36 mo from 2003 through 2008.

Our study protocol, data and safety monitoring plan, consent form, and all participant-related materials were approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards at ISU (ID 02-199) and at UCD (ID 200210884-2). Approvals for the dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) procedures were obtained from each institution’s Institutional Review Board and the State Department of Public Health in Iowa and California. At prebaseline screening, each woman was provided a written description and verbal explanation and written informed consent (signed after staff responded to questions) prior to any study procedures.

Participant screening and selection

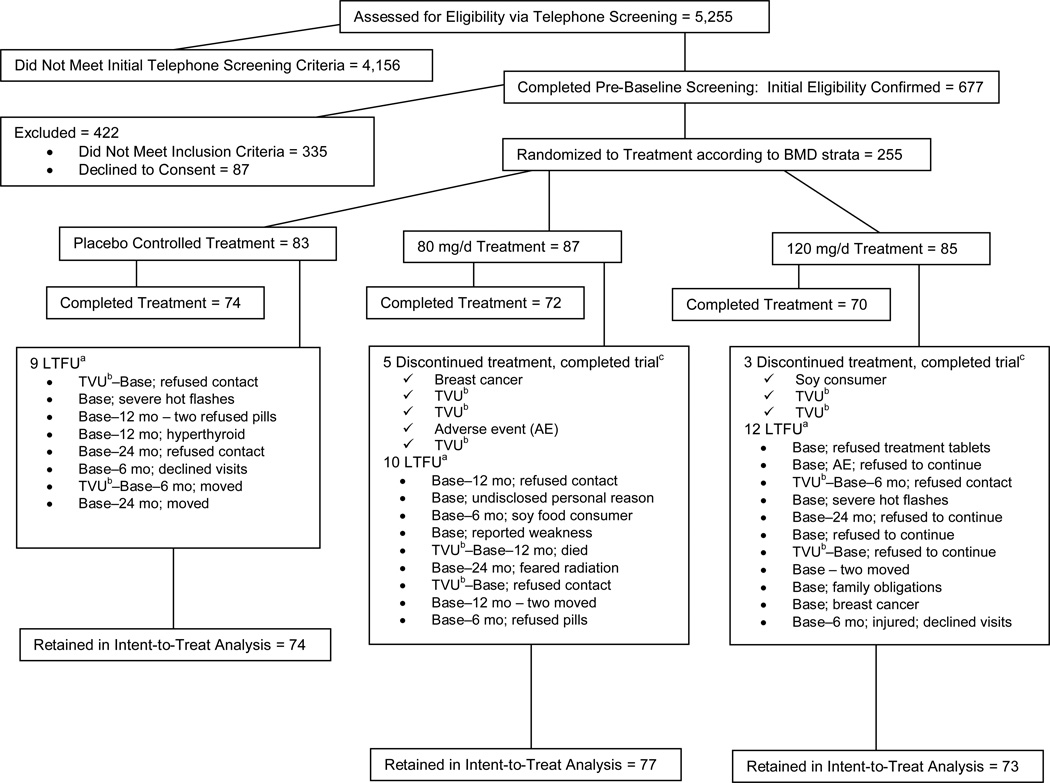

We recruited participants (2003 through 2005) from the state of Iowa and the greater Sacramento and Bay Area regions in northern California, primarily through direct mailing lists, stories in local newspapers, and local/regional radio advertisements. Women who responded (N=5255) to outreach materials were screened initially via telephone (Figure 1) to identify healthy women aged <65 y who had undergone natural menopause (cessation of menses 1 through 8 y), were not experiencing excessive vasomotor symptoms, were nonsmokers, and had a BMI (kg/m2) from 18.5 through 29.9. We excluded vegans because they would likely be soy food consumers, and women who were high alcohol consumers (>7 servings/wk) because alcohol interferes with hormone metabolism9. We excluded women diagnosed with chronic disease, who had a first-degree relative with breast cancer, or who used medication chronically (current: cholesterol lowering or antihypertensive; past 3 mo: antibiotics; past 6 mo: calcitonin, estrogen/progestogen creams; past 12 mo: oral hormones/estrogen or selective estrogen receptor modulators; ever: bisphosphonates).

Figure 1.

Study participant CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) diagram8

a Altogether, 31 women were lost to follow-up (LTFU; 2 at Iowa State University [ISU], 29 at University of California at Davis [UCD]). Diagram indicates the last time point [baseline (base) or 6, 12, 24 mo] at which we collected data for each woman who was LTFU and reasons for discontinuance.

b Eleven women at UCD had thickened endometria [(determined by transvaginal ultrasound (TVU)] and thus did not meet inclusion criterion (≤5 mm). BMD, bone mineral density

c Eight women discontinued treatment but completed trial (1 at ISU, 7 at UCD)

Women who met the initial screening criteria (N=677) were invited to the clinic for further eligibility assessment (Figure 1). We measured height and weight to confirm BMI; we used a Delphi-W QDR DXA bone densitometer (Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA) to assess BMD eligibility. Because the SIRBL project focused on disease prevention in women who had “normal” BMD, we excluded women with BMD lumbar spine and/or proximal femur T scores that were low (>1.5 SD below young adult mean) or high (>1.0 SD above mean) and those with evidence of previous or existing spinal fractures. Once she qualified on the basis of BMD, each woman had blood drawn for a chemistry profile. We excluded women with laboratory evidence of diabetes mellitus; abnormal renal, liver, and/or thyroid function; or abnormal lipid profile. On the basis of our entry criteria, we randomly assigned 255 participants to treatment.

Each participant obtained a signed medical release form from her personal physician; she was also required to complete an annual physical and a mammogram, as well as breast and gynecologic examinations prior to initiation of study treatment. We monitored endometrial thickness (measured at the thickest portion) using transvaginal ultrasonography (Siemens Aspen Advanced at ISU and Siemens Accusone Sequoia at UCD) at baseline and at 12 and 36 mo. Transvaginal ultrasound evaluation included length, width, and axial measurements of the uterus and ovaries (both right and left), as well as the internal echo content. Gynecologists also evaluated the cul de sac for any fluid and the cervix. Irregularities or abnormalities in any of these structures were evaluated, documented, and follow-up medical care was provided as needed. We excluded women at baseline with endometrial thickness >5.0 mm, except for those with values of 5.0–6.0 mm who underwent an endometrial biopsy that proved normal. At baseline, 11 women at UCD who had endometrial thickness >5.0 mm were inadvertently started on treatment, but were instructed to cease treatment, because of the safety concern of isoflavone exposure. These women were invited to continue with follow-up safety examinations throughout the study. Nine women at UCD had BMI values beyond our inclusion criteria (1 woman: <18.5; 8 women: ≥30.0), 4 at UCD did not meet the criterion for time since last menstrual period (TLMP [current age–menopausal age]; 1 woman: <1 y; 3 women: >8 y), and 2 (1 at UCD and 1 at ISU) had a lumbar spine BMD T score slightly below (−1.6) or above (+1.1) our cutoff (−1.5 to ≤+1.0). Our Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), appointed by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), granted waivers that sanctioned continued treatment of women with values beyond our criteria for BMI, TLMP, and BMD, since these violations did not pose a safety threat.

Randomization and treatment

To balance treatment allocation with respect to factors that may have influenced response-to-treatment, participants at each site (ISU, UCD) were stratified according to initial total proximal femur BMD (high, medium, low) on the basis of the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database population values10. Once participants met inclusion/exclusion criteria, they were randomly assigned at each site within each BMD strata to 1 of 3 treatment groups: 1) placebo control, 2) 80 mg isoflavones, or 3) 120 mg isoflavones. The ratio of genistein to daidzein to glycitein (aglycone form) in these tablets was 1.3 to 1.0 to 0.3, similar to that found in soybeans. An independent researcher at ISU confirmed that the actual and formulated, respectively, isoflavone doses (mean ± SD) were similar to those tested by the Archer Daniels Midland Co (Decatur, IL): control=0 compared with 0.3±0.4 mg; 80 mg=89.5±5.0 compared with 84.3±4.5 mg; 120 mg=124.0±7.7 compared with 122.5±3.4 mg. Participants in each group were instructed to take 3 compressed tablets/d. To preserve the double-blind of the study, bottles did not indicate treatment assignment. For further details, the reader is referred to the parent project manuscript8.

Interviewer-administered, validated health-related questionnaires

To verify the health status and obtain health-related data of each participant, at prebaseline we used a health and medical history questionnaire11,12. We also gathered data on prescription and over-the-counter medications (indication, dose, unit, frequency, duration, administration route) at each time point, as well as previous and/or present use of dietary supplements (which they were asked to discontinue) and current usual alcohol intake. Each woman was asked questions about menstrual history (e.g., age at menarche and date of final period), previous use of estrogen or hormone therapy, and pregnancy and lactation history using a reproductive history questionnaire13,14. To account for habitual soy food consumption, as well as to verify avoidance of soy foods during the trial, we used a soy food questionnaire15.

Anthropometric measures

A trained research assistant assessed anthropometric measures for each participant. Body weight (to the nearest 0.1 kg) was measured with women wearing minimal clothing, using a balance beam scale (abco Health-o-meter; Health-o-meter Inc, Bridgeview, IL) at ISU and an electronic scale (Circuits and Systems Inc, E. Rockaway, NY) at UCD. Standing height without shoes was measured (to the nearest 0.1 cm) with the use of a wall-mounted stadiometer (Ayrton stadiometer, model S100; Ayrton Corp, Prior Lake, MN). We calculated BMI based upon weight and standing height measures.

Biological samples

Phlebotomists collected overnight fasted blood samples between 7:00 and 8:00 am. We separated serum from whole blood, centrifuged for 15 min (4°C) at 1300 X g, and stored serum and plasma aliquots at −80°C until analyzed. Certified clinical laboratories (LabCorp, Kansas City, KS, for ISU; UCD Medical Center, Sacramento, CA, for UCD) analyzed serum samples for general health markers, including the complete blood count with differential, chemistry panel, and thyroid screen (TSH and free T4 if TSH was abnormal). We measured plasma concentrations (in duplicate) of ultra-sensitive 17 β-estradiol and estrone-sulfate by radioimmunoassay (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Austin, TX) and SHBG by ELISA (IBL America, Minneapolis, MN) in batch at the University of Minnesota. Free estradiol (fraction not protein-bound) and bioavailable estradiol (albumin-bound plus free estradiol fractions) were calculated for each participant using the equations by Vermeulen et al.16 and association constants estimated by the method of Mazer et al.17. All samples from a given participant were analyzed in the same batch. Intra-assay coefficients of variation were 4.4% for 17 β-estradiol, 4.3% for estrone-sulfate, and 5.8% for SHBG.

Monitoring adverse events

Our DSMB monitored all outcomes and adverse events semiannually, whereas we documented serious adverse events and provided details to our DSMB and respective Institutional Review Board committees within 24 h of participant notification. We monitored adverse events using a health status update form, review of a health diary and medication update, chemistry profile, and complete blood count at each visit; bone loss annually (in consultation with our DSMB, considered an adverse event if cumulative bone loss was ≥8% at 12 mo, ≥10% at 24 mo, or ≥12% at 36 mo); and endometrial thickness via transvaginal ultrasound at 12 and 36 mo. Any abnormality noted on the woman’s physical examination report constituted an adverse event. Adverse events were also defined as any self-reported health event that required treatment or resulted in a new diagnosis or new/worsened signs or symptoms, such as blood clots, vaginal bleeding, dizziness, headaches, insomnia, or fatigue. We required follow-up with our consulting physician if change was noted in her transvaginal ultrasound scan, such as a 300% increase from baseline or thickened endometrium (>5 mm), or appearance/development or increase in the size of a polyp, fibroid, or cyst. Our consulting physician at each site determined whether or not an abnormality in the scan constituted an adverse event and performed the appropriate follow-up (i.e., monitoring, endometrial biopsy, hysteroscopy).

Compliance

We evaluated treatment compliance by calculating the difference between the number of tablets provided and tablets returned by each woman at each visit. To classify participants as either compliant (≥80%) or noncompliant (<80%), we used the 36-mo cumulative percentage compliance8. Urinary isoflavone concentrations verified compliance but did not classify participants into “compliant” or “noncompliant” groups based on isoflavone excretion because of the relatively large inter-individual variability in isoflavone excretion.

Statistical power and analyses

Power analysis was based upon the primary bone outcomes of interest for the overall SIRBL study8, including the intent-to-treat women (N=224; control: n = 74; 80 mg/d: n = 77; 120 mg/d: n = 73), with blocking by site (ISU, UCD) and prebaseline proximal femur BMD strata (high, medium, low). Statistical analyses were performed with the use of SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Inc, Cary, NC) and R software (version 3.01; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria) with results considered statistically significant (2-sided) at p<0.05. Descriptive statistics with 255 women at baseline included median (minima, maxima) values for all data, because the outcome data and most variables were not normally distributed. Hormone data are presented at each time point for all women who returned for visits. Change (mm) in endometrial thickness data are presented at each time point (baseline, 12 mo, 36 mo) separately according to site because of site differences in ultrasound equipment. The primary analysis was intent-to-treat18, which included all data from all women who had a follow-up BMD at 36 mo (N = 224), regardless of treatment compliance. Because the assumption of normality was not supported by the data, we used non-parametric ANOVA to determine the effect of treatment on concentrations of circulating hormones and on endometrial thickness. To determine whether treatment differences were consistent across all time points, we used tests for parallel profiles (based on Wilks’ lambda criterion) for change in endometrial thickness at each site. To determine the effect of treatment on adverse events, we used a Poisson regression model with an extra dispersion parameter that links the natural logarithms of rates of occurrence of adverse events to treatment and site effects. The extra dispersion parameter is needed to account for the over-dispersion in the response variable (i.e., its variance is larger than its mean). The most common adverse events according to treatment are reported.

Secondary analyses included all women from the intent-to-treat analysis who were protocol compliant (>80%, based on her cumulative percentage compliance) and for whom we had complete data for variables included in the models. One UCD participant did not have a baseline blood sample and thus did not remain in the analyses for compliant women. The linear mixed-effects longitudinal model assessed the effect of treatment after adjustment for covariates that might influence the response of endometrial thickness across time points. We modeled the natural logarithm of endometrial thickness to stabilize its variance. The fitted model included site and treatment as obligatory design variables. The ISU site effect was part of each model intercept, whereas the UCD site effect was indicated separately. Classes of variables in modeling the outcomes of interest included biologically plausible independent variables that we hypothesized would be related to endometrial thickness. These included: age or estrogen exposure (age at menopause–age at menarche) or TLMP at baseline; weight or whole-body fat mass at baseline; plasma concentrations of 17 β-estradiol, estrone-sulfate, and SHBG across time points; serum TSH concentration across time points; alcohol intake (usual weekly intake estimated from questionnaire) at baseline; and lactation duration (in mo per pregnancy carried to term). The model selection was guided by a stepwise procedure based upon Akaike’s information criterion to provide the best predictive model for the outcome19. We employed a cut-off of p≤0.10 as the acceptable Type 1 error rate for covariates in the model to allow consideration of variables that may be borderline, in the event they might provide a greater understanding of potential biologic phenomena. After transforming endometrial thickness, residual diagnostics indicated homogeneous variability. No other violations of mixed-effects model assumptions emerged during the analysis.

RESULTS

Enrollment and retention of participants

Among the 677 women who completed prebaseline screening and met initial eligibility, 37.7% met subsequent criteria and were randomly assigned to treatment at each site (122 at ISU, 133 at UCD) within each proximal femur BMD strata (high, medium, low). Among the 255 women randomly assigned to treatment, 31 women (12.2%) were lost to follow-up (2 at ISU, 29 at UCD) and 8 women (3.1%) discontinued treatment but completed the trial (1 at ISU, 7 at UCD). Reasons for discontinuance and loss to follow-up are provided in Figure 1. The 11 participants at UCD (8.3%) who had thickened endometria (>5 mm, thus they did not meet inclusion criterion) were removed from treatment; five of these 11 women completed study visits. Altogether, 224 women (intent-to-treat) were retained (120 at ISU, 104 at UCD), and 216 remained on treatment (119 at ISU, 97 at UCD) for 36 mo. Participants in treatment groups for intent-to-treat and compliant models, respectively, were as follows: n = 74 and 72 in placebo control; n = 77 and 67 in 80 mg/d; and n = 73 and 69 in 120 mg/d group.

Compliance

Based upon returned tablet counts, compliance was excellent in women who remained on treatment (N = 216), with 209 (96.8% [117 at ISU and 92 at UCD]) of 216 women who achieved ≥80% compliance (cumulative at 36 mo)8. One participant at UCD did not have a baseline blood sample and thus did not remain in the compliant analyses (N = 208). Median compliance (all women who remained on treatment) likewise was high, but was significantly (p ≤0.0001) higher at ISU (98.0% [94.0, 99.6%]) than at UCD (95.2% [88.0, 98.2%]). We noted no difference in median compliance values across the 3 treatment groups (p = 0.49) or across BMD strata within site (p = 0.39). Median (lower quartile, upper quartile values) compliance was 97.0% (93.1, 99.2%) for the placebo control (n = 74), 96.1% (91.3, 98.6%) for the 80 mg/d (n = 72), and 97.2% (91.8, 99.3%) for the 120 mg/d (n = 70) group. Consistent with excellent compliance, median values from baseline to 36 mo for urinary daidzein (nmol/d) did not change (302 to 195; NS) in the control group, increased from 208 to 8706 in the 80 mg/d (p ≤ 0.0001) and increased from 304 to 11,411 in the 120 mg/d (p ≤0.0001) group. Similar patterns were noted in the excretion of other urinary isoflavone metabolites among the three treatment groups.

Characteristics of participants

Descriptive characteristics and data are presented in Table 1. We found no statistically significant differences among the treatment groups at baseline for any of these variables. Women ranged in age from 45.8 to 65.0 y; TLMP ranged from 0.8 to 10.0 y. Despite our efforts to enroll women from all racial/ethnic backgrounds (self-reported as defined by the National Institutes of Health), we enrolled predominantly white (92%) women. At baseline, BMI values ranged from 17.8 to 32.7; approximately half of the women had values <25. Median weight and height remained stable over time, as did BMI, whole-body lean mass, and whole-body fat mass. Whole-body fat mass as assessed by DXA indicated wide variability among women. Further details on these results are provided in the parent project manuscript8.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Reproductive History According to Treatment at Baseline

| Characteristic | Treatmenta | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo Control n=83 |

80 mg/d n=87 |

120 mg/d n=85 |

Total N=255 |

||

| Age (yr) | Median | 54.2 | 54.3 | 54.7 | 54.3 |

| Min, Max | 45.8, 61.4 | 48.2, 65.0 | 46.5, 62.0 | 45.8, 65.0 | |

| Time since Last Menstrual Period | |||||

| [Baseline test date minus date of | Median | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| last menstrual period] (yr)b | Min, Max | 0.8, 7.9 | 0.9, 10.0 | 1.0, 8.0 | 0.8, 10.0 |

| Age at Menopause (yr) | Median | 51.0 | 50.0 | 51.0 | 51.0 |

| Min, Max | 42.0, 57.0 | 44.0, 60.0 | 41.0, 59.0 | 41.0, 60.0 | |

| Endogenous Estrogen Exposure | |||||

| [Age at last menstrual cycle minus | Median | 38.0 | 38.0 | 38.0 | 38.0 |

| age at menarche] (yr) | Min, Max | 30.0, 45.0 | 31.0, 46.0 | 27.0, 48.0 | 27.0, 48.0 |

| Pregnancies Carried to Term (N) | N | 69 | 78 | 66 | 213 |

| Median | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| Min, Max | 1.0, 5.0 | 1.0, 5.0 | 1.0, 5.0 | 1.0, 5.0 | |

| Total Lactation (mo) | N | 54 | 59 | 53 | 166 |

| Median | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | |

| Min, Max | 0.5, 99.0 | 1.0, 132.0 | 0.25, 96.0 | 0.25, 132.0 | |

| Past Hormone Therapy | N | 38 | 35 | 36 | 109 |

| (estrogen+progestogen) (mo) | Median | 15.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 |

| Min, Max | 0.25, 120.0 | 0.25, 108.0 | 0.0c, 70.0 | 0.0, 120.0 | |

| Past Estrogen Therapy(mo) | N | 6 | 5 | 8 | 19 |

| Median | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | |

| Min, Max | 1.0, 6.0 | 1.0, 3.0 | 1.0, 6.0 | 1.0, 6.0 | |

| Past Progestogen/Progesterone | N | 12 | 6 | 8 | 26 |

| Therapy (mo) | Median | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.5 |

| Min, Max | 1.0, 6.0 | 1.0, 4.0 | 1.0, 8.0 | 1.0, 8.0 | |

| Body Weight (kg) | Median | 66.1 | 68.7 | 66.6 | 67.3 |

| Min, Max | 50.4, 87.7 | 43.7, 94.5 | 46.3, 88.5 | 43.7, 94.5 | |

| Standing Height (cm) | Median | 165.6 | 164.6 | 165.6 | 165.5 |

| Min, Max | 152.3, 182.1 | 150.6, 177.4 | 146.3, 182.2 | 146.3, 182.2 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Median | 24.3 | 25.0 | 24.6 | 24.6 |

| Min, Max | 19.8, 31.7 | 17.8, 32.7 | 18.9, 31.0 | 17.8, 32.7 | |

| Whole Body Fat (%) | Median | 35.4 | 34.8 | 34.2 | 34.5 |

| Min, Max | 24.1, 49.9 | 18.4, 45.4 | 18.1, 55.9 | 18.1, 55.9 | |

| Alcohol Intake (g/week) | N | 66 | 63 | 60 | 189 |

| Median | 32.4 | 50.9 | 47.1 | 45.0 | |

| Min, Max | 1.3, 228.0 | 3.0, 302.4 | 2.0, 258.3 | 1.3, 302.4 | |

| Endometrial Thickness (mm), | N | 40 | 41 | 41 | 122 |

| Iowa State University (ISU) site | Median | 1.30 | 1.60 | 1.70 | 1.50 |

| Min, Max | 0.80, 3.40 | 0.60, 3.60 | 0.60, 5.10 | 0.60, 5.10 | |

| Endometrial Thickness (mm), | N | 41 | 41 | 40 | 122 |

| University of California-Davis (UCD) | Median | 3.00 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.60 |

| sited | Min, Max | 1.00, 6.00 | 0.30, 6.50 | 1.00, 5.00 | 0.30, 6.50 |

At baseline, there were no statistical differences among treatment groups for these characteristics

Four women (2 in 80 mg/d, 1 in 120 mg/d, 1 in control group) at UCD were beyond range of inclusion criterion for time since last menstrual period (1 through 8 yr), but these women were included in the trial because intervention did not pose a safety threat.

One woman in 120 mg/d group started hormone therapy, but stopped within days and thus min value=0.

Statistics do not include 11 women with thickened endometria who were incorrectly randomized to treatment at UCD prior to receipt of their TVU report results; SIRBL discontinued treatment for these 11 women. Five of these women at UCD had endometrial thickness >5.0 (5.5, 5.9, 6.0, 6.0, 6.5) at baseline. Four women with endometrial thickness greater than 5.5 mm underwent endometrial biopsies but had normal results; thus, these women were included in these statistics and remained on treatment.

Serum analytes/hormones and endometrial thickness

Nonparametric ANOVA indicated that there were no differences among treatment groups in circulating hormone concentrations (Table 2) at various time points. Results did not differ when analyses were performed on calculated free and bioavailable estradiol. However, there were a few site differences, not attributable to treatment. At baseline, women from UCD had significantly higher estrone-sulfate (p≤;0.0001) and lower (p=0.0002) TSH compared with women at ISU. Differences persisted for estrone-sulfate at each subsequent time point (p≤0.0001) and for TSH at 6 mo (p=0.044), 12 mo (p=0.022), and 36 mo (p=0.0058). At 12 months UCD had lower (p=0.032) estrone-sulfate in the 120 mg group than the other two groups. Sex hormone-binding globulin trended higher at ISU than UCD at baseline (p=0.071) and at 6 mo (p=0.049), but otherwise differences between sites were not noted.

Table 2.

Reproductive Hormone and Thyroid Hormone Concentrations at Each Time Pointa

| Analyte | Baseline | 6 Months | 12 Months | 24 Months | 36 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma(Sample Size unless otherwise noted): | N=254 | N=242 | N=236 | N=227 | N=223 |

| 17 β-Estradiol (pg/mL) | |||||

| Median | 9.10 | 8.42 | 8.19 | 8.28 | 8.70 |

| Min, Max | 2.50, 103.46 | 2.50, 114.09 | 2.50, 48.96 | 2.50, 41.65 | 2.50, 47.07 |

| Free Estradiol (pg/mL) | |||||

| Median | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| Min, Max | 0.04, 2.64 | 0.04, 2.88 | 0.04, 1.27 | 0.04, 1.05 | 0.05, 1.23 |

| Bioavailable Estradiol (pg/mL) | |||||

| Median | 6.27 | 5.76 | 5.58 | 5.62 | 5.98 |

| Min, Max | 1.15, 77.43 | 1.25, 84.62 | 1.10, 37.25 | 1.21, 30.73 | 1.36, 35.97 |

| Estrone-Sulfateb(ng/mL) | |||||

| Median | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.70 |

| Min, Max | 0.19, 3.26 | 0.21, 3.81 | 0.03, 1.93 | 0.17, 2.86 | 0.18, 1.76 |

| Sex Hormone-Binding Globulinb (nmol/L) | |||||

| Median | 27.40 | 28.19 | 26.65 | 27.14 | 27.00 |

| Min, Max | 3.38, 91.57 | 3.52, 79.57 | 3.54, 80.24 | 5.05, 73.16 | 1.49, 75.02 |

| Serum | |||||

| Thyroid-Stimulating Hormoneb(TSH) (µIU/mL) | N=255 | N=242 | N=236 | N=227 | N=224 |

| Median | 2.46 | 2.30 | 2.54 | 2.35 | 2.51 |

| Min, Max | 0.34, 10.76 | 0.03, 9.03 | 0.01, 23.26 | 0.21, 13.00 | 0.54, 13.76 |

| Free Thyroxinec (Free T4) (ng/dL) | N=22 | N=24 | N=33 | N=10 | N=13 |

| Median | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.05 |

| Min, Max | 0.65, 1.39 | 0.72, 1.39 | 0.73, 2.08 | 0.52, 1.69 | 0.75, 1.29 |

Nonparametric ANOVA indicated that there were no treatment differences in circulating hormone concentrations at any time point, except at 12 months UCD had lower (p=0.032) estrone sulphate in the 120 mg group than the other two groups.

At baseline, women from the University of California at Davis (UCD) site had significantly higher estrone sulfate (p≤0.0001) and lower (p=0.0002) TSH compared with women at Iowa State University (ISU). Differences persisted for estrone sulfate (p≤0.0001) at each subsequent time point and for TSH at 6 mo (p=0.044), 12 mo (p=0.022), and 36 mo (p=0.0058). Sex hormone-binding globulin trended higher at ISU than UCD at baseline (p=0.071) and at 6 mo (p=0.049).

Free thyroxine analysis was only run on those samples that revealed abnormal TSH values (<0.35 or >5.5 µIU/mL) at each time point.

Median values for endometrial thickness (mm) declined from baseline through 36 mo (Figure 2) at ISU (1.5 to 1.1) and at UCD (2.6 to 1.9). The two geographic sites remained separate for analysis (except for linear mixed-effects longitudinal model [Table 5] where we accounted for site difference) because endometrial thickness (mm) values were statistically different (p≤0.0001) between sites at each time point due to site differences in transvaginal ultrasound equipment. Although the values for endometrial thickness were approximately 30–40% higher at UCD than ISU, these differences persisted throughout treatment and did not influence the interpretation of results. Based upon nonparametric ANOVA for treatment differences (absolute) among groups, no differences in endometrial thickness emerged at any time point (Chi-Square p-values ranged from 0.12–0.69). Likewise, nonparametric ANOVA indicated that treatment had no effect on percentage change at 12 months (Chi-Square p-value=0.46) or at 36 months (Chi-Square p-value=0.28). Tests for parallel profiles (based on Wilks’ lambda criterion) to determine whether treatment differences in endometrial thickness were consistent across all time points indicated that there was no interaction between treatment and time for either ISU (p=0.41) or UCD (p=0.70), further indicating no effect of treatment over time.

Figure 2. Endometrial Thickness (mm): Iowa State University (ISU, left panel); University of California-Davis (UCD, right panel).

| Iowa State University (ISU) Site: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Point | Placebo Control | 80 mg/day | 120 mg/day |

| Baseline | 40 | 41 | 41 |

| 12 Months | 40 | 40 | 37 |

| 36 Months | 40 | 41 | 37 |

| University of California at Davis (UCD): | |||

| Time Point | Placebo Control | 80 mg/day | 120 mg/day |

| Baseline | 41 | 41 | 40 |

| 12 Months | 39 | 38 | 33 |

| 36 Months | 33 | 32 | 31 |

Adverse events

The adverse events (Table 3) were classified into 14 broad physiological systems: cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, gynecologic, hematologic, metabolic, nervous, nonspecific (i.e., bone, joint, spine disorders, etc.), ophthalmic, pathological, pulmonary, renal, and skin. In a given system, there was a tendency for higher rates of reporting adverse events at ISU than UCD, but site differences were not significant, with the exception of upper respiratory infections (p≤0.0001) and pathological conditions (p=0.0017), including sinusitis and other infections, that were more common at ISU than UCD. The pathological conditions that were more common at ISU than UCD, respectively, included sinusitis (23 versus 3 cases) and a variety of infections (21 versus 5 cases), such as bacterial, otitis media, and benign cysts. The pathological conditions that were more common at UCD than ISU, respectively, included malignancies (7 versus 2 cases), such as squamous cell carcinoma and carcinoid (lung) tumor. The most common adverse event, regardless of treatment group, was upper respiratory infection, followed by non-specific complaints. However, we observed a significant treatment effect on the genitourinary system (p=0.005; Table 3), with a greater number of events in the 80 mg/d, but fewer events in the 120 mg/d group. Nevertheless, there were relatively few genitourinary events during the course of three years in these postmenopausal women. Spotting or bleeding due to small polyps or fibroids was not related to changes in endometrial thickness. During the course of treatment, 10 women required further evaluation: five women (2 at ISU, 3 at UCD) underwent an endometrial biopsy and five women (3 at ISU, 2 at UCD) underwent a hysteroscopy (distributed across treatment groups), with normal pathology reported by the attending physician. No other significant treatment effect emerged for other systems. The most common adverse events in each treatment are shown in Table 4. The number of adverse events was 412 in the control group (n=76), 401 in the 120 mg/d group (n=76), and 427 in the 80 mg/d group (n=82). Given the long-term nature of this study, adverse events (other than respiratory infections) were relatively uncommon. One woman (120 mg/d group) had excessive lumbar spine bone loss at 24 mo (28.3%) and 36 mo (212.1%) and another woman (control group) had excessive proximal femur bone loss at 24 mo (28.7%). Each woman with excessive bone loss was notified and advised to report these results to her primary care physician for follow-up care.

Table 3.

Adverse Events for Major System, by Site and Treatmenta

| AE System | Site | Treatment | Rateb | Count | Exposure | Site effect (p value) |

Treatment effect (p value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | ISU | Placebo | 0.050 | 2 | 120.00 | 0.67 | 0.68 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.049 | 2 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.102 | 4 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.053 | 2 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.125 | 5 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.056 | 2 | 107.75 | |||||

| Endocrine | ISU | Placebo | 0.325 | 13 | 120.00 | 0.091 | 0.38 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.122 | 5 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.255 | 10 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.132 | 6 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.150 | 6 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.111 | 4 | 107.75 | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | ISU | Placebo | 0.450 | 18 | 120.00 | 0.50 | 0.25 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.683 | 28 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.383 | 15 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.423 | 16 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.450 | 18 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.418 | 15 | 107.75 | |||||

| Genitourinary | ISU | Placebo | 0.150 | 6 | 120.00 | 0.78 | 0.005 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.366 | 15 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.128 | 5 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.185 | 7 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.300 | 12 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.084 | 3 | 107.75 | |||||

| Gynecologic | ISU | Placebo | 0.250 | 10 | 120.00 | 0.085 | 0.32 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.537 | 22 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.255 | 10 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.238 | 9 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.175 | 7 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.251 | 9 | 107.75 | |||||

| Hematologic | ISU | Placebo | 0.300 | 12 | 120.00 | 0.33 | 0.084 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.268 | 11 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.409 | 16 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.106 | 4 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.250 | 10 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.390 | 14 | 107.75 | |||||

| Metabolic | ISU | Placebo | 0.450 | 18 | 120.00 | 0.51 | 0.69 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.415 | 17 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.664 | 26 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.582 | 22 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.425 | 17 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.278 | 10 | 107.75 | |||||

| Nervous | ISU | Placebo | 0.300 | 12 | 120.00 | 0.97 | 0.99 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.244 | 10 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.102 | 4 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.132 | 5 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.175 | 7 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.334 | 12 | 107.75 | |||||

| Nonspecific | ISU | Placebo | 1.050 | 42 | 120.00 | 0.31 | 0.88 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.854 | 35 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 1.302 | 51 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.846 | 32 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 1.075 | 43 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.752 | 27 | 107.75 | |||||

| Ophthalmic | ISU | Placebo | 0.050 | 2 | 120.00 | 0.29 | 0.18 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.073 | 3 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.128 | 5 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.079 | 3 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.100 | 4 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.195 | 7 | 107.75 | |||||

| Pathological | ISU | Placebo | 0.850 | 34 | 120.00 | 0.0017 | 0.13 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.512 | 21 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.511 | 20 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.344 | 13 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.250 | 10 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.390 | 14 | 107.75 | |||||

| Pulmonary | ISU | Placebo | 2.250 | 90 | 120.00 | ≤0.0001 | 0.83 | |

| 80 mg/d | 1.610 | 66 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 1.736 | 68 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.449 | 17 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.975 | 39 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.780 | 28 | 107.75 | |||||

| Renal | ISU | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 120.00 | 0.92 | 0.77 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.024 | 1 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.026 | 1 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.026 | 1 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0 | 0 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.028 | 1 | 107.75 | |||||

| Skin | ISU | Placebo | 0.275 | 11 | 120.00 | 0.72 | 0.36 | |

| 80 mg/d | 0.146 | 6 | 123.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.281 | 11 | 117.50 | |||||

| UCD | Placebo | 0.185 | 7 | 113.50 | ||||

| 80 mg/d | 0.175 | 7 | 120.00 | |||||

| 120 mg/d | 0.251 | 9 | 107.75 | |||||

Results were obtained by fitting a Poisson regression model with an extra dispersion parameter that links the natural logarithms of rates of occurrence of AEs to treatment and site effects.

Incidence rates are calculated using the expected counts divided by exposure time. For women who completed the entire study, exposure time=36 mo; for women who dropped out, exposure time=time point when woman was last examined plus ½ of next time interval.

Table 4.

Most Common Adverse Events by Treatment (using frequencies, considering the primary system affected)

| Placebo Control (from 76 subjects, nAE = 412) |

80 mg/day (from 82 subjects, nAE = 427) |

120 mg/day (from 76 subjects, nAE = 401) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %a | No. | %a | No. | %a | |||

| Upper Respiratory Infection | 98 | 24% | Upper Respiratory Infection | 95 | 22% | Upper Respiratory Infection | 86 | 21% |

| LDL Increase | 15 | 4% | Urinary Tract Infection | 23 | 5% | Pain | 11 | 3% |

| Sinusitis | 14 | 3% | Flu | 17 | 4% | LDL Increase | 10 | 2% |

| Gastroenteritis | 13 | 3% | Gastroenteritis | 15 | 4% | Flu | 9 | 2% |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 13 | 3% | Sinusitis | 12 | 3% | Sinusitis | 9 | 2% |

| Joint Trauma | 12 | 3% | Pain | 11 | 3% | Joint Trauma | 8 | 2% |

| Flu | 11 | 3% | LDL Increase | 10 | 2% | Urinary Tract Infection | 8 | 2% |

| Insomnia | 10 | 2% | Tooth Disorder | 8 | 2% | Gastroenteritis | 6 | 1% |

| Pain | 10 | 2% | Joint Trauma | 7 | 2% | Headache | 6 | 1% |

| Headache | 9 | 2% | Insomnia | 6 | 1% | Tooth Disorder | 6 | 1% |

| Tooth Disorder | 4 | 1% | Iron Decrease | 5 | 1% | Iron Decrease | 3 | 1% |

Percent of adverse events for a given adverse event is based on the number of adverse events in relation to the total number for each treatment.

We documented 18 serious adverse events among 16 women during the 36 mo: 4 in the control group, 8 in the 80 mg/d group, and 6 in the 120 mg/d group. In the control group, one woman experienced a myocardial infarction, one woman a breast reduction, and one woman experienced two occurrences of benign parathyroid tumors. In the 80 mg/d group, one woman experienced two occurrences of anterior cystocele (bladder disorder), one woman a traumatic bone fracture, one woman a hip replacement, one woman died due to infection, one woman contracted malaria while traveling overseas, one woman had a carcinoid tumor, and one woman had breast cancer. In the 120 mg/d group, one woman experienced a benign parathyroid tumor, one woman a hysterectomy, two women traumatic bone fractures, and two women breast cancer. Each serious adverse event was reviewed carefully by our DSMB and deemed not related to treatment.

Predictors of endometrial thickness

The model predicting the endometrial thickness response (using the natural logarithm) to treatment with compliant women (N = 208) across time points (Table 5) was significant (p≤0.0001), indicating that estrogen exposure (p=0.0013), plasma 17 β-estradiol (p=0.0086), and alcohol intake (p=0.023) contributed significantly to the endometrial thickness response. Although neither the 80 nor 120 mg/d treatment dose exerted an effect (p=0.57, p=0.43, respectively) on endometrial thickness across time, site (consistently higher values at UCD) and time (endometrial thickness decreased at both sites from baseline through 36 mo) both exerted significant (p≤0.0001) effects. However, the interaction between treatment and time (log likelihood ratio=3.996; df=2) was not significant (p=0.14). In this group of women, as estrogen exposure decreased or as plasma 17-β estradiol decreased, there was greater loss in endometrial thickness. As alcohol intake increased, the decline in endometrial thickness lessened. Serum TSH remained in the model, but did not reach statistical significance (p=0.066). The independent variables that did not remain in the model were body weight or body fat mass, lactation duration, plasma estrone concentration, and SHBG.

Table 5.

Linear Mixed-Effects Longitudinal Modela: Endometrial Thicknessb Response Across Time Points (N=208, compliant model)

| Outcome Variable | Independent Variable | Parameter Estimate |

Standard Error |

pValuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial Thicknessb |

Intercept | −0.401 | 0.262 | 0.13 |

| Site (ISU=0) | 0.528 | 0.049 | ≤0.0001 | |

| Treatment (80 mg) | 0.032 | 0.056 | 0.57 | |

| Treatment (120 mg) | 0.043 | 0.055 | 0.43 | |

| Time (mo) | −0.008 | 0.001 | ≤0.0001 | |

| Estrogen Exposured (y) | 0.022 | 0.007 | 0.0013 | |

| Plasma 17-β Estradiol (pg/mL) | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.0086 | |

| Alcohol Intakee (g/week) | −0.001 | 0.0004 | 0.023 | |

| Serum Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (µIU/L) | −0.020 | 0.011 | 0.066 | |

Overall model vs model with obligatory design variables only: likelihood ratio = 12.149; df=4; p≤0.0001. Likelihood ratio based on maximum likelihood estimation; estimates and significances based on restricted maximum likelihood estimation.

Natural logarithm of endometrial thickness as variance stabilizing transformation.

P values are based on asymptotic normality of t-distribution; variables left in model were significant at p≤0.10 level (acceptable Type I error rate in modeling endometrial thickness). Additional variables (i.e., body weight, lactation duration, etc.) did not remain in model. The interaction between treatment and time (log likelihood ratio=3.996; df=2) was not significant (p=0.14).

Calculated at baseline, estrogen exposure in years = age at menopause – age at menarche; estrogen exposure was not related to plasma 17-β estradiol (Pearson correlation coefficient = −0.05).

Represents usual weekly alcohol intake at baseline, which was assessed at baseline from a dietary questionnaire.

DISCUSSION

The current study is unique in that we assessed the long-term overall safety and potential endometrial stimulation using transvaginal ultrasound among a fairly large group of postmenopausal women who consumed (with excellent compliance) soy isoflavone (80 or 120 mg/d) tablets for 3 years. Nonetheless, there were limitations to this study: We had numerous exclusion criteria; these women were relatively healthy and agreed to participate for three full years. The women were sampled from two distinct U.S. locations and hence did not represent women from the east coast or southern states. Despite our attempts to include a broader spectrum of women, they were relatively homogeneous from a socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and cultural perspective. Thus, these women were not necessarily representative of postmenopausal women in general. In addition, a greater number of women at UCD (n=29) than ISU (n=2) were lost to follow-up, in part because more women at UCD relocated during the study than those at ISU. Also, we speculate that because the ISU site was more rural than the UCD site, women in Iowa were more accustomed to traveling long distances for services and thus the majority of ISU women did not find it burdensome to attend visits (many traveled 3 to 4 hours; a few had moved to distant states but remained in the study). We also speculate that the more urban lifestyle at the UCD site imposed different and perhaps greater challenges in traveling to the clinic site. Although both sites implemented similar follow-up contact procedures, the UCD site experienced greater staff turnover during the course of the study and hence had less continuity of personnel contact than participants at ISU.

We report no treatment effect on circulating hormone concentrations (or on other circulating analytes, not reported), no treatment effect on endometrial thickness, no appreciable treatment effect on adverse events, except that the 80 mg/d group had higher (27 events) genitourinary adverse events compared with the 120 mg/d group (8 events). The majority of these genitourinary adverse events were urinary tract infections, clustering in a small group of women. Collectively, these results indicate that soy isoflavones did not adversely impact circulating hormone concentrations or the genitourinary system in these postmenopausal women. The lower number of genitourinary adverse events in the higher dose suggested the relative safety of soy isoflavones on this system. By a wide margin, the greatest number of adverse events was for upper respiratory infections (Table 4), particularly among women in Iowa (Table 3, pulmonary system), presumably due to a longer flu season than in California.

Comparisons herein are limited to the human model, since there are sufficient data to provide insights solely from the human literature. The current study did not document treatment-induced effects on serum 17 β-estradiol, free estradiol, bioavailable estradiol, estrone-sulfate, SHBG, or TSH, consistent with a systematic review and meta-analysis that reported no statistically significant effect of soy or isoflavones on 17 β-estradiol, estrone, or SHBG in postmenopausal women20. Our results are also similar to a study using red clover-derived isoflavones21, which did not show a treatment effect on serum reproductive hormones in 205 postmenopausal women. Further, our results demonstrated no treatment effect on thyroid function, concurring with other studies in postmenopausal women: Levis et al.22 used soy isoflavones (200 mg/d) for two years in 168 women, Steinberg et al.3 used soy hypocotyl isoflavones (80 or 120 mg/d) for two years in 362 women, and Bitto et al.23 used genistein (54 mg/d) for three years in 138 women. Given the long-term nature of these studies with various formulations, it is reasonable to believe that these doses of soy isoflavones do not negatively impact thyroid function in postmenopausal women.

In addition, we report no effect of treatment on endometrial thickness at any time point, with a decline in thickness at both sites across treatments, particularly from baseline to 12 mo. Prior to the initiation of our clinical trial, few data in humans on the endometrial safety of isoflavones had been published, with few exceptions. A small randomized crossover design study6 indicated that neither a low-(1.0) nor high-(2.0) isoflavone (mg/kg/d) diet for 3 mo had a significant effect on either vaginal cytology or endometrial biopsy results in premenopausal women. In addition, Upmalis et al.24 reported no change in endometrial thickness or vaginal maturation index with either treatment (50 mg/d genistin + daidzin vs. placebo) after 12 wk. However, once our project was underway25,26,27, but prior to publishing the results from this manuscript2,3,5, additional studies have been published more firmly establishing the endometrial safety of isoflavones. The earlier studies were relatively short-term (≤12 mo), whereas the later studies demonstrating safety are based upon longer term exposure to soy isoflavone treatment.

Han et al.25 reported that soy isoflavones (100 mg/d) for four months had no proliferative effect on the endometrium as assessed by transvaginal ultrasound exams. Likewise, Penotti et al.26 documented that soy isoflavones (72 mg/d) for six months had no stimulatory effect on the endometrium as assessed by transvaginal ultrasound exams or on uterine pulsatility index as assessed by Doppler velocimetry. Murray et al.27 used four groups (25 g/d soy protein isolate with 120 mg/d isoflavones + 0.5 mg/d estradiol vs. 25 g/d soy protein isolate with 120 mg/d isoflavones + 1.0 mg/d estradiol vs. 0.5 mg/d estradiol + placebo vs. 1.0 mg/d estradiol + placebo) to test the hypothesis that six months of soy protein with isoflavones would oppose the proliferative effects of exogenous estradiol on the endometrium. Although they did not find that soy protein plus isoflavones protected the endometrium from exogenous estradiol, these researchers reported that endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial stromal and epithelial cellular proliferation, and endometrial thickness were similarly affected in all groups. The design of this last short-term study was not similar to our study, despite providing similar daily isoflavone doses, but provided valuable information that soy protein isolate with isoflavones did not protect the endometrium from estradiol-induced hyperplasia in postmenopausal women.

Among the longer term studies, D’Anna et al.5 indicated that genistein (54 mg/d) improved vasomotor symptoms at 12 mo, and found no adverse effect on the endometrium or vagina, either at baseline or after 24 mo. A 24 mo (2 y) study3 using soy hypocotyl isoflavones (80/d or 120 mg/d, doses similar to our study), reported transvaginal ultrasound measurements from the California cohort (N=116) with no significant differences in endometrial thickness among the three treatment groups. Likewise, Palacios et al.2 did not report any significant change in endometrial thickness (98.4% inactive or atrophic, 0.3% proliferative at 12 mo), with only one case of simple hyperplasia diagnosed among 197 post-baseline interpretable biopsies. Global safety was rated as either excellent or good by 99% of investigators and patients after 36 mo of isoflavone (70 mg/d) extract treatment. In contrast, one report7 indicated that longer-term (up to 5 y) soy isoflavone exposure was associated with an increased (3.8%) occurrence of endometrial hyperplasia (five with simple and one with complex hyperplasia), whereas no cases of endometrial carcinoma occurred in either group. It is important to note that this last study used a relatively high dose of isoflavones (150 mg/d) and did not demonstrate hyperplasia at 30 mo, but reported hyperplasia with longer exposure (60 mo).

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that there is evidence for the endometrial safety of isoflavones over a 3 y period, in that these compounds do not exert uterotrophic effects when consumed in doses of ≤120 mg/d. Only one study7 has raised concern with use longer than 36 mo (5 y), indicating that a higher dose of isoflavones (150 mg/d) may cause a slightly higher risk of simple endometrial hyperplasia in some (<3%) women. In contrast, our study did not find evidence of endometrial stimulation with 120 or 80 mg/d of soy isoflavone intake for 3 years in these postmenopausal women. Additionally, there are no data to suggest that soy food intake promotes endometrial hyperplasia.

Although soy isoflavone treatment did not alter the decline in endometrial thickness, a few factors modified slightly the decline in endometrial thickness from baseline to 36 mo. For example, women in this study who had longer lifetime estrogen exposure and higher circulating 17-β estradiol concentration experienced less loss in endometrial thickness from baseline to 36 mo. Interestingly, estrogen exposure was not related to plasma 17-β estradiol (Pearson correlation coefficient = −0.05) and thus each of these estrogen variables uniquely prevented the loss of endometrial thickness. We were somewhat surprised that women with a higher usual alcohol intake experienced less decline (slightly) in endometrial thickness from baseline to 36 mo, considering that our participants were not heavy drinkers. There is some evidence that alcohol intake elevates circulating estrogen28,29, which in turn might alter endometrial thickness, but further large studies have not corroborated an association between alcohol intake and endometrial cancer risk30,31, thereby dispelling the notion that alcohol intake promotes risk for endometrial cancer. Nevertheless, the predominant factor that contributed, as expected, to the decline in endometrial thickness was time, reflecting the increase in TLMP.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, regardless of treatment, postmenopausal women in this study experienced a progressive decrease over time in endometrial thickness, which was particularly marked from baseline to 12 mo. Our study verified the long-term overall safety of consuming soy isoflavone (80 or 120 mg/d) tablets by postmenopausal women who displayed excellent compliance. We found no evidence of a treatment effect on endometrial thickness, adverse events, or circulating hormone concentrations, most notably thyroid function, during a three year period.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The SIRBL study team thanks all of our participants because without their dedication our study could not have been completed. We acknowledge our phlebotomists and students (graduate and undergraduate alike) who reported early and steadfastly for testing at our clinic sites. We thank the James R Randall Research Center, Archer Daniels Midland Company (Decatur, IL), which supplied the ingredients free of charge, with the use of certified good manufacturing procedures, for the treatment tablets (Novasoy), as well as Atrium Biotechnologies Inc, which compressed the ingredients into tablets. We thank GlaxoSmithKline (Moon Township, PA) for donating the calcium and vitamin D supplements (Os-Cal). We also thank our DSMB (Dennis Black, chair) and Joan McGowan, Musculoskeletal Diseases Branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, who provided scrutiny, guidance, and valuable feedback throughout the trial.

We also thank the following individuals who worked on various aspects of the SIRBL project—project coordinators: Oksana Matvienko (ICU), Allyson Sage (ICU), and Carol Chandler (UCD); database managers/SAS programmers for statistical analysis for DSMB reports: Christine Chiechi (UCD) and Kathy Shelley (ISU) (merged data sets); medical consultants: Bonnie Beer (McFarland Clinic, Ames, IA) and TomWold (MatherWomen’s Health Clinic, CA), who read/interpreted the transvaginal ultrasound reports, reviewed abnormal exam results, and performed medical procedures as needed; clinical monitor: Debbie Sellmeyer (University of California at San Francisco); laboratory technicians: Erik Gertz (UCD), Michael Wachter (UMN), and Steven McColley (UMN); DXA operators: Kathy Hanson (ISU), who analyzed/reviewed DXA scans, and Barbara Gale (UCD); and budget specialist: Barbara Clark (ISU).

Funding: Supported mainly by a grant (RO1 AR046922) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS); also supported by the Nutrition and Wellness Research Center at Iowa State University; USDA/ARS, Western Human Nutrition Research Center (5306-51530-006-00D), Clinical and Translational Science Center, Clinical Research Center, University of California (1M01RR19975-01); and National Center for Medical Research (UL1 RR024146).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The content and views expressed in this article are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies or those of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine at the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Funding agencies did not play a role in data collection, management, analysis, interpretation, or in manuscript preparation or review. The NIH and USDA are equal opportunity providers and employers.

Conflict of Interest: MS Kurzer is a member of the Soy Nutrition Institute Scientific Advisory Board; otherwise, the authors had no known conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

D. Lee Alekel, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Ulrike Genschel, Department of Statistics, Iowa State University, Ames, IA.

Kenneth J Koehler, Department of Statistics, Iowa State University, Ames, IA.

Heike Hofmann, Department of Statistics, Iowa State University, Ames, IA.

Marta D Van Loan, US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service, Western Human Nutrition Research Center, and University of California, Davis, CA.

Bonnie S. Beer, McFarland Clinic, Ames, IA.

Laura N Hanson, Mayo Validation Support Services, Rochester, MN.

Charles T Peterson, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Food & Drug Administration, White Oak, MD.

Mindy S Kurzer, Department of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Minnesota, St Paul, MN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ursin G, Sun C-L, Koh W-P, et al. Associations between soy, diet, reproductive factors, and mammographic density in Singapore Chinese women. Nutr Cancer. 2006;56:128–135. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5602_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palacios S, Pornel B, Vázquez F, Aubert L, Chantre P, Marès P. Long-term endometrial and breast safety of a specific, standardized soy extract. Climacteric. 2010;13:368–375. doi: 10.3109/13697131003660585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg FM, Murray MJ, Lewis RD, et al. Clinical outcomes of a 2-y soy isoflavone supplementation in menopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:356–367. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.008359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colacurci N, De Franciscis P, Atlante M, et al. Endometrial, breast and liver safety of soy isoflavones plus Lactobacillus sporogenes in post-menopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29:209–212. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.738724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Anna R, Cannata ML, Marini H, et al. Effects of the phytoestrogen genistein on hot flushes, endometrium, and vaginal epithelium in postmenopausal women: A 2-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Menopause. 2009;16:301–306. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318186d7e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan AM, Underhill KE, Xu X, Lavalleur J, Phipps WR, Kurzer MS. Modest hormonal effects of soy isoflavones in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3479–3484. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unfer V, Casini ML, Castabile L, Mignosa M, Gerli S, Di Renzo GC. Endometrial effects of long-term treatment with phytoestrogens: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alekel DL, Van Loan MD, Koehler KJ, et al. The soy isoflavones for reducing bone loss (SIRBL) study: A 3-y randomized controlled trial in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:218–230. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen NR, Grønbaek M. Interactions between intakes of alcohol and postmenopausal hormones on risk of breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1109–1113. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, et al. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:468–489. doi: 10.1007/s001980050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alekel DL, St Germain A, Peterson CT, Hanson KB, Stewart JW, Toda T. Isoflavone-rich soy protein isolate attenuates bone loss in the lumbar spine of perimenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:844–852. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alekel DL. PhD dissertation. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois-Urbana; 1993. Contributions of physical activity, body composition, age, and nutritional factors to total and regional bone mass in premenopausal aerobic dancers and exercisers. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morabia A, Costanza MC. International variability in ages at menarche, first live birth, and menopause: World Health Organization collaborative study of neoplasia and steroid contraceptives. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:1195–1205. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.St. Germain A, Peterson CT, Robinson J, Alekel DL. Isoflavone-rich or isoflavone-poor soy protein does not reduce menopausal symptoms during 24 weeks of treatment. Menopause. 2001;8:17–26. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirk P, Patterson RE, Lampe J. Development of a soy food frequency questionnaire to estimate isoflavone consumption in U.S. adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:558–563. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00139-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3666–3672. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazer NA. A novel spreadsheet method for calculating the free serum concentrations of testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, estradiol, estrone and cortisol: With illustrative examples from male and female populations. Steroids. 2009;74:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials. Br Med J. 1999;319:670–674. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allison PD. Logistic regression using the SAS system—theory and application. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 1999. Multicollinearity. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooper L, Ryder JJ, Kurzer MS, et al. Effects of soy protein and isoflavones on circulating hormone concentrations in pre- and postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:423–440. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkinson C, Warren RM, Sala E, et al. Red clover-derived isoflavones and mammographic breast density: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R170–R179. doi: 10.1186/bcr773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levis S, Strickman-Stein N, Ganjei-Azar P, Xu P, Doerge DR, Krischer J. Soy isoflavones in the prevention of menopausal bone loss and menopausal symptoms: A randomized, double-blind trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1363–1369. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bitto A, Polito F, Atteritano M, et al. Genistein aglycone does not affect thyroid function: Results from a three-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3067–3072. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Upmalis DH, Lobo R, Bradley L, Warren M, Cone FL, Lamia CA. Vasomotor symptom relief by soy isoflavone extract tablets in postmenopausal women: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Menopause. 2000;7:236–242. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200007040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han KK, Soares JM, Jr, Haidar MA, de Lima GR, Baracat EC. Benefits of soy isoflavone therapeutic regimen on menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:389–394. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penotti M, Fabio E, Modena AB, Rinaldi M, Omodei U, Viganó P. Effect of soy-derived isoflavones on hot flushes, endometrial thickness, and the pulsatility index of the uterine and cerebral arteries. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1112–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray MJ, Meyer WR, Lessey BA, Oi RH, DeWire RE, Fritz MA. Soy protein isolate with isoflavones does not prevent estradiol-induced endometrial hyperplasia in postmenopausal women: A pilot trial. Menopause. 2003;10:456–464. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000063567.84134.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandera EV, Kushi LH, Olson SH, Chen WY, Muti P. Alcohol consumption and endometrial cancer: Some unresolved issues. Nutr Cancer. 2003;45:24–29. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC4501_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rinaldi S, Peeters PH, Bezemer ID, et al. Relationship of alcohol intake and sex steroid concentrations in blood in pre- and post-menopausal women: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:1033–1043. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loerbroks A, Schouten LJ, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and endometrial cancer risk: Results from the Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:551–560. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-0127-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fedirko V, Jenab M, Rinaldi S, et al. Alcohol drinking and endometrial cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]