Abstract

Depression often accompanies chronic illness. Study aims included determining (1) the level of current depression (Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-8 ≥ 10) for two sets of Chronic Disease Self-Management Programs (CDSMP) participants; (2) if depression or other outcomes improved for those with PHQ-8 ≥ 10; and (3) if outcomes differed for participants with or without depression. This study utilized longitudinal secondary data analysis of depression cohorts (PHQ-8 ≥ 10) from two independent translational implementations of the CDSMP, small-group (N = 175) and Internet-based (N = 110). At baseline, 27 and 55 % of the two samples had PHQ-8 10 or greater. This decreased to 16 and 37 % by 12 months (p < 0.001). Both depressed and non-depressed cohorts demonstrated improvements in most 12-month outcomes (pain, fatigue, activity limitations, and medication adherence). The CDSMP was associated with long-term improvements in depression regardless of delivery mode or location, and the programs appeared beneficial for participants with and without depression.

Keywords: Depression, Self-management, Patient education, Chronic disease

There is growing attention to the interplay between physical and mental health. In particular, several studies have noted the association of depression with other chronic diseases [1–5]. For example, Corbin and Strauss [1], in a landmark qualitative study, determined that emotions were one of three major concerns for people with chronic illness. Studies have also suggested “depression is associated with poor adherence to medication across a range of chronic diseases” [6, 7].

In addition, several studies have found an association between low self-efficacy and depression [8, 9] with one concluding “enhancing self-efficacy levels might reduce anxiety and depression” [9]. The Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) was designed to increase self-efficacy as one means to manage chronic conditions. Improvements in self-efficacy by CDSMP programs participants are associated with improved health outcomes [10, 11].

The CDSMP programs were developed for people with one or more chronic conditions. In fact, participants usually have two or more conditions. In the U.S. National Study small-group CDSMP [12], participants reported a mean of 2.6 chronic conditions (SD = 1.4), ranging from 1 to 10. Unlike most studies where the population is carefully screened to assure that all participants have similar characteristics, participants in CDSMP studies are very heterogeneous.

The CDSMP in both small-group and on-line formats (also known as Internet-based Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (ICDSMP)) has been shown to improve health symptoms, including depression, and health behaviors. The effect sizes, however, are small [13, 14]. For example, in the U.S. National Study [13], there was a significant 12-month reduction in a measure of depression, but the effect size of the change (Cohen’s d, computed as change divided by baseline standard deviation) was 0.22, considered a small effect size [15]. The heterogeneity of the population could account for the small to moderate effect sizes, as not all subjects have all symptoms. In particular, many participants in these programs did not have symptoms of depression and thus would not be expected to show improvements in depression measures.

Given the above background, the question arises whether individuals with symptoms of depression, as indicated by high Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) scores, are likely to benefit from generic chronic disease programs. To examine these issues, we performed secondary data analyses on data from two independent CDSMP translation studies, one presented via small-group workshops in the USA and one utilizing Internet-based workshops in Canada. We used the data to determine within each of the two programs:

The percentage of small-group and Internet participants who met the criteria for current depression

If the interventions were effective in reducing depression and improving other outcome measures for those with depression

If those with depression had similar or different results for other outcome variables compared to those without current depression

METHODS

Data sources

The two data sets chosen for secondary data analyses are both from translational studies presented in community setting. The first consists of data from a large national study conducted in 22 sites in the USA. All participants in this study attended a 6-week small-group Chronic Disease Self-Management workshop [12]. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at both Stanford University and Texas A&M University. The academic investigators had no role in leader training, recruitment for workshops, or program implementation, which were carried out by the participating organizations in their usual fashion.

The second study was a version of the same program delivered via the Internet. The ICDSMP, known as Healthy Living Canada, was delivered Canada-wide [16]. ICDSMP workshops were funded and administered by Alberta Health Services with software support and assistance from the U.S. National Council on Aging (NCOA). The investigators again had no role in training facilitators, recruitment for workshops, or program implementation, with the exception that on-line facilitators were monitored by mentors associated with investigators. Rather than comparing the two programs, this study treats them as two independent replications of the effect of the CDSMP on people with depression.

Both the U.S. National Study of the CDSMP and the Healthy Living Canada ICDSMP included the PHQ-8 measure of depression among the self-reported outcome measures. Both programs demonstrated small but statistically significant mean decreases in PHQ-8 scores, and both programs included participants with and without symptoms of depression at baseline [12, 16].

The interventions

The CDSMP is designed to impart skills that are common across a variety of chronic diseases. Thus, its participants can have almost any mental or physical chronic condition. The CDSMP is peer led and utilizes face-to-face small groups meeting 2.5 h a week for 6 weeks.

In a randomized trial, the CDSMP was found to improve a number of health statuses and health-related behaviors as well as self-efficacy. Improvements were found to persist up to 2 years [13, 17]. The CDSMP has been widely used and disseminated, and there have been several studies of the small-group CDSMP for participants with chronic diseases in diverse populations, including Spanish speakers in the USA, Chinese in both China and Australia, Bangladeshis in London, African-Americans in the USA, and British in England [18–24]. For the U.S. National translation study, more than 1,000 people from 22 sites in the USA were recruited for a 1-year longitudinal study [12]. The English-language participants in this study comprise the small-group data set for the current study. Workshop leaders for this translation study were trained by Stanford-certified CDSMP master trainers, and the programs offered were not modified or locally adapted from standard CDSMP protocols.

Although large numbers of people have attended the CDSMP, there are those who do not like small groups, live in isolated areas where groups are not available, or have disabilities that make it difficult to attend groups. Thus, the ICDSMP was designed as a second mode of delivery. We view small groups and the Internet as two modes to deliver the same intervention.

The ICDSMP was originally evaluated with a population from all over the USA in a 1-year randomized trial. Like the small-group program, it was found to improve health status and self-efficacy, as well as reduce emergency department visits [14]. A second longitudinal (non-randomized) study for people served by the English National Health Service found that the ICDSMP was both feasible and associated with positive results [25]. More recently the Alberta Health Services in Canada chose to replicate the English study using a nationwide sample [16]. Participants in this study make up the data set for the on-line (ICDSMP) analyses in the current study.

Both the content and the process of the 6-week ICDSMP are based on and similar to that of the small-group program. Specifically, both programs have the same content and integrate self-efficacy theory throughout [26]. Both are led by trained peers, are highly interactive, and place emphasis on participants assisting each other. Both are 6 weeks long, include planning and problem solving as key elements, and utilize the same reference book. They differ in that the CDSMP participants and leaders talk face to face in real time, while in the ICDSMP, participants and leaders interact asynchronously using threaded bulletin boards. The ICDSMP workshops consist of 20 to 25 persons compared to 10 to 15 participants in the CDSMP workshops. The program as offered by Alberta Health Services was the same program that is currently being offered by NCOA in the USA under the name “Better Choices, Better Health.”

Participants

The U.S. National Study participants consisted of adults enrolled in English-language CDSMP workshops delivered nationwide between August 2010 and April 2011. Each participating CDSMP delivery site recruited people for workshops in their usual fashion, which included referrals from organizations specifically serving older adults (e.g., senior centers, Area Agencies on Aging), health care facilities, and social service organizations, as well as self-referrals from a variety of recruitment activities including community flyers, brochures, and health fairs. Participant eligibility criteria for this study included (1) having at least one self-reported chronic disease or condition; (2) enrolling in a CDSMP workshop delivered in English; (3) attending at least one of the first two class sessions; (4) not having taken CDSMP previously; (5) completing a baseline questionnaire; and (6) consenting to being in this study. There were over 900 English-speaking participants in 103 workshops presented by 19 organizations in 15 states [12].

The Healthy Living Canada ICDSMP participants were recruited from across Canada using social media, flyers, and posters. Inclusion criteria were similar to the small-group CDSMP workshops with participants required to login to the on-line workshops at least once. The study involved 277 participants from nine provinces and territories who enrolled in 12 on-line workshops [16]. Since this was considered a pilot program to test the feasibility of its use for wider dissemination by Alberta Health Services, it was only funded for 12 on-line workshops, and enrollment was stopped at that point.

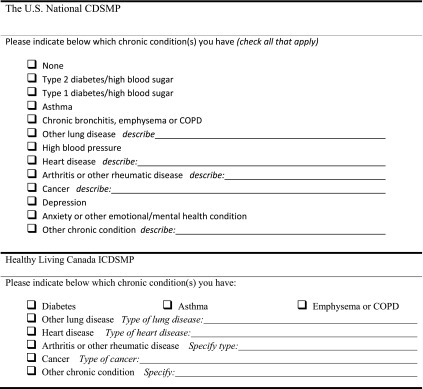

The list of possible self-reported chronic conditions that participants were allowed to choose from differed somewhat between the two programs. Table 1 shows the actual baseline questions participants were given. In both cases, participants were allowed to specify any other condition they considered a chronic disease. Only when potential participants indicated they had no chronic disease were they were excluded from the study (although some without a chronic condition might still attend the workshops, for example if they were accompanying a spouse with chronic diseases).

Table 1.

Enrollment questionnaires and sections for indicating types of chronic conditions

Most participants in both studies reported multiple chronic conditions. In the U.S. National Study, 30 % of participants listed depression as one of their self-reported conditions [12], but only 5 % of these reported depression as their only condition (N = 14). Unfortunately, depression was not one of the criteria conditions included in the Healthy Living Canada Study baseline questionnaire.

Measures

PHQ-8 depression measure

Depression is the major variable of interest for both segmenting the samples and as an outcome measure. For both studies, it was measured using the PHQ-8. The original PHQ is a 21-item scale developed in the late 1990s “for making criteria-based diagnoses of depressive and other mental disorders commonly encountered in primary care” [27, 28]. The PHQ-9 is a nine-item subset of the PHQ that focuses specifically on depression. The PHQ-9 was assessed among 6,000 patients and found to be a “reliable and valid measure of depression severity” [28]. Item 9 of the PHQ-9 asks about thoughts of being better off dead or hurting oneself. The item has been used to assess suicide risk. It is often omitted from questionnaires, yielding the PHQ-8 measure of depression. Kroenke and colleagues found that the PHQ-8 was a useful measure for population-based studies as well as clinical diagnoses and that “a cut point > or = 10 can be used for defining current depression” [29]. More recently, Razykov and colleagues compared the PHQ-9 to the PHQ-8 in 1,022 outpatients with the chronic condition of coronary artery disease (CAD). They concluded that item 9 was not an accurate suicide screen and that “the PHQ-8 may be a better option than the PHQ-9 in CAD patients” [30]. PHQ-8 scores range from 0 to 24 and had an internal consistency reliability of 0.89 among the Healthy Living Canada participants. For both the PHQ-9 and the PHQ-8, a decrease of 5 points or more has been used as a general indicator of clinically significant improvement [31, 32].

Other outcome measures

In addition to PHQ-8 depression, six outcomes were measured in both studies. These consisted of three health indicators (pain, fatigue, and social role/activity limitation), one behavior (medication adherence), and two utilization (emergency department visits and hospitalizations) variables. Single-item visual numeric scales were used to measure pain and fatigue [33]. These are adaptations of visual analogue scales [34], with a range of 0 (no pain/fatigue) to 10 (severe pain/fatigue). Health interference with social roles was measured using the social role/activity limitations scale [35]. It consists of the mean of four items asking about health interfering with activities with a range of 0 (not at all) to 4 (almost totally). Medication adherence was measured using the sum of 4 yes–no items that asked about participants forgetting or stopping their medication [36]. It thus had a range of 0 to 4, with higher values indicating less adherence. Emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalization were obtained from participant self-report of how many times they had been to the ED or stayed overnight in the hospital in the past 6 months. These reports have been found to correlate well with chart audits [37].

Data analyses

All analyses were conducted separately within each of the studies. The subsets with PHQ-8 scores of 10 or greater became the depression cohorts, which were then analyzed in greater detail. First, we examined whether there was significant change in depression between baseline and 12 months using paired t tests. We then examined change scores within the depression cohorts for the six additional outcome variables, again using paired t tests to determine if 12-month changes were significantly greater than would be expected had they been sampled from a population that had no changes. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were computed as the change scores divided by the baseline standard deviations. Effect sizes of d = 0.2 were considered small, d = 0.5 medium, and d = 0.8 large [15]. We also computed the percentages of participants in the programs who improved or worsened by 5 or more units on the PHQ-8 score since, as noted above, a change of 5 or more is considered clinically significant [32].

The depression cohorts were compared to cohorts with lower depression scores using analyses of covariance. Changes in outcomes, including PHQ-8 depression, were examined with baseline outcome scores and demographic variables as covariates. These analyses were used to determine if those who had PHQ-8 scores indicative of depression did or did not have improvements comparable to those with low (non-depression) PHQ-8 scores. We would hypothesize that the depression cohort would do at least as well as the non-depressed in both studies.

Results of the data analyses are presented separately for the U.S. National Study participants and for the Health Living Canada participants.

RESULTS

The U.S. National Study

Baseline characteristics

For all English-language participants in the U.S. National Study, the mean baseline PHQ-8 score was 6.6 (SD = 5.5). At baseline, 27 % of the U.S. sample had PHQ-8s of 10 or above (N = 258). The mean age was 66.6 (SD = 13.7) and the mean years of education was 13.8 (SD = 3.0). Participants were predominantly female (83 %), 72 % were non-Hispanic White, and 38 % were married. Additional details regarding the demographic characteristics of the overall U.S. National Study can be found elsewhere [12].

Within the depression cohort of the U.S. National Study, 83 % of participants were female, 76 % White, and 33 % married (Table 2). The mean age was 60.0 (SD = 14.5) and mean years of education 13.4 (SD = 2.9). Those with indications of depression tended to be younger (60.0 versus 68.9, t = 8.78, p < 0.001), slightly less educated (13.4 years of school versus 13.9, t = 2.45, p = 0.01), and less likely to be married (33 versus 40 %, chi-square = 4.16, p = 0.04) than those without indications of depression. Table 2 shows the baseline demographic characteristics for both the depression cohort and those without indications of depression.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic characteristics of depression cohort and those with PHQ-8 less than 10 (non-depressed)

| Demographic variable | U.S. National CDSMP (English speakers) | Healthy Living Canada ICDSMP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-8 < 10 (non-depressed) (N = 692) | PHQ-8 ≥ 10 (depression cohort) (N = 258) | PHQ-8 < 10 (non-depressed) (N = 129) | PHQ-8 ≥ 10 (depression cohort) (N = 148) | |

| Age (mean) | 68.9 (SD = 12.6) | 60.0 (SD = 14.5) | 49.0 (SD = 12.2) | 46.6 (SD = 10.4) |

| Years of education (mean) | 13.9 (SD = 3.06) | 13.4 (SD = 2.9) | 14.9 (SD = 2.65) | 14.6 (SD = 2.68) |

| Non-Hispanic White (percent) | 79.7 % | 75.6 % | 90.7 % | 96.6 % |

| Married (percent) | 39.8 % | 32.6 % | 64.3 % | 61.0 % |

| Female (percent) | 82.7 % | 82.6 % | 74.4 % | 77.7 % |

Changes in depression

In the U.S. National Study, the proportion with PHQ-8 of 10 and above was 15.7 % at 12 months compared to 27 % at baseline (differences from baseline, chi-square = 202.5, p < 0.001). For participants with 12-month questionnaires, there was a 12-month reduction of 1.25 (effect size Cohen’s d = 0.23, p < 0.001) [12]. Looking at the depression cohort (only participants with a PHQ-8 of 10 or more at baseline, N = 258), there was a statistically significant decrease in PHQ-8 of 3.5 (approximately 1.1 effect sizes) at 12 months when compared to baseline (Table 3). The percentage of the U.S. National Study depression cohort who decreased by 5 or more on PHQ-8 between baseline and 12 months was 40.7 % (Table 4). The percentage who increased by 5 or more was 5.7 %.

Table 3.

Baseline, 12-month changes, and participants with indications of depression who completed 12-month questionnaires

| Variable name (possible range) | U.S. National CDSMP (English speakers), N = 175 | Healthy Living Canada ICDSMP, N = 110 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline mean (SD) | 12-month change, mean (SD) | p | Baseline mean (SD) | 12-month change, mean (SD) | p | |

| PHQ-8 Depression (0–24) | 13.9 (3.78) | −3.47 (5.75) | <0.001 | 15. 5 (4.34) | −4.30 (5.51) | <0.001 |

| Pain (0–10) | 6.43 (2.48) | −0.600 (2.55) | 0.002 | 6.91 (2.67) | −0.691 (1.97) | <0.001 |

| Fatigue (0–10) | 7.02 (2.29) | −0.869 (2.71) | <0.001 | 7.66 (1.47) | −0.691 (2.05) | <0.001 |

| Activity limitation (0–4) | 2.38 (0.936) | −0.287 1.17) | 0.001 | 2.67 (0.898) | −0.295 (0.906) | 0.001 |

| Medication adherence (0–4) | 1.43 (1.28) | −0.240 (1.06) | 0.003 | 1.45 (1.18) | −0.311 (1.18) | 0.009 |

| Number of emergency department visits (last 6 months) | 0.451 (1.53) | 0.0 (1.91) | 1.00 | 0.573 (1.14) | −0.235 (1.00) | 0.015 |

| Number of hospitalizations (last 6 months) | 1.22 (3.46) | 0.815 (6.53) | 0.103 | 0.091 (0.440) | −0.027 (0.515) | 0.579 |

For all health indicators and behaviors, a lower score is desirable. Mean changes are changes in scale scores or in number of visits. P values are from pair-wise t tests indicating the likelihood that a change this large could have occurred if sampling form a population with zero change

Table 4.

U.S. National Study 12-month changes, comparing participants with PHQ-8 10 or above (depression cohort) at baseline with those with PHQ-8 less than 10 (non-depressed)

| Variable name (possible range) | U.S. National Study (English speakers), N = 677 | Healthy Living Canada, N = 220 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-8 < 10 (non-depressed) change mean (SD) | PHQ-8 ≥ 10 (depression cohort) change mean (SD) | Effect size | p | PHQ-8 < 10 (non-depressed) change mean (SD) | PHQ-8 ≥ 10 (depression cohort) change mean (SD) | Effect size | p | |

| PHQ-8 Depression, (mean, 0–24) | −0.306* (3.11) | −3.47*** (5.75) | 0.518 | <0.001 | 0.146 (4.06) | −4.30*** (5.51) | 0.806 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-8 Depression (% decreased 5 or more) | 6.5 % | 40.7 % | n/a | <0.001 | 10.0 % | 44.6 % | n/a | <0.001 |

| Pain (0–10) | −0.268* (2.74) | −0.600** (2.55) | 0.114 | 0.160 | −0.227 (2.31) | −0.691*** (1.97) | 0.152 | 0.111 |

| Fatigue (0–10) | −0.267* (2.62) | −0.869*** (2.71) | 0.296 | 0.010 | −0.636** (2.27) | −0.691*** (2.05) | 0.020 | 0.852 |

| Activity limitation (0–4) | −0.086^ (1.27) | −0.287*** (1.17) | 0.185 | 0.044 | −0.284** (1.04) | −0.296*** (0.906) | 0.011 | 0.931 |

| Medication adherence (0–4) | −0.137** (1.03) | −0.240** (1.06) | 0.087 | 0.256 | −0.116 (1.02) | −0.311** (1.18) | 0.172 | 0.217 |

| Number of emergency department visits (last 6 months) | 0.002 (0.613) | 0.00 (1.91) | 0.001 | 0.989 | −0.073 (1.25) | −0.236* (1.00) | 0.151 | 0.285 |

| Number of hospitalizations (last 6 months) | 0.032 (0.527) | 0.058 (0.957) | 0.056 | 0.734 | 0.009 (0.459) | −0.027 (0.515) | 0.053 | 0.581 |

For mean changes for all health indicators and behaviors, a lower score is desirable. P value columns (except row 2) are from analyses of covariance indicating the likelihood that the difference in 12-month least-squared adjusted means could have been sampled from a population where changes were zero after controlling for baseline scores and demographic variables. Row 2 p values are from chi-squares. Effect sizes are calculated as the difference in mean change scores divided by the pooled baseline SD. For changes from baseline within each column, p values from pair-wise t tests are indicated by the following: ^≤0.10, *≤0.05, **≤0.01, ***≤0.001

Table 4 compares the depression cohort with the non-depressed within each study. As expected, those with baseline depression were more likely to have improvements in depression. In order to compare the proportion that changed by 5 or more on PHQ-8 to the depression cohort, we also computed the percentages for the non-depressed cohorts. In the U.S. National study, 6.5 % decreased by 5 or more and 6.5 % increased by 5 or more within the non-depressed cohort. These percentages are shown in the second row of Table 4, along with the percentages for the depression cohort (described above).

Changes in outcome variables

Looking at the six additional outcomes for the U.S. depression-cohort participants, four of six had statistically significant improvement at 12 months (Table 3). Comparing the depression cohort with the non-depression cohort, participants with baseline depression had significantly greater improvements in fatigue and activity limitation at 12 months (Table 4).

Twelve-month completers versus non-completers

Using intent-to-treat methodology (no change assumed for those with missing follow-up questionnaire), the p values for changes in PHQ-8 remained unchanged for the depression cohort in the U.S. National CDSMP. The 12-month mean PHQ-8 change score was reduced from −3.47 to −2.35 by substituting 0.0 change for those missing data at 12 months. There were no significant differences at baseline in PHQ-8 depression scores for those who completed and those who failed to complete 12-month follow-up questionnaires.

Using intent-to-treat methodology, the p values for 12-month change scores for all outcomes remained unchanged. When we compared the baseline values of those who failed to complete with those who completed questionnaires, there were a few differences within the depression cohort for the U.S. National Study. Twelve-month non-completers had greater emergency department visits at baseline (0.45 versus 0.98, t = 2.2, p < 0.05) and tended to be younger (56 versus 62, t = 2.94, p = 0.01, respectively).

Healthy Living Canada Study

Baseline characteristics

In the Healthy Living Canada Study, the mean PHQ-8 at baseline for all participants was 10.9 (SD = 6.1). The proportion at baseline with depression (PHQ-8s of 10 or more) was 55 % (N = 148). Among all participants in the Healthy Living Canada dissemination study, 94 % were non-Hispanic White, 63 % were married, and 76 % were female. The mean age was 47.7 (SD = 11.3) and the mean years of education was 14.7 (SD = 2.67). Further information about the demographics of the overall Healthy Living Canada participants can also be found elsewhere [16].

Among the depression cohort of the Healthy Living Canada Study (Table 2), 78 % were female, 97 % White, and 61 % married (Table 2). The mean age was 46.6 (SD = 10.4) and mean years of education 14.6 (SD = 2.7). There were no significant differences in demographic variables between the depression cohort and the participants with low depression scores within the Canadian sample.

Changes in depression

For the Healthy Living Canada participants, at 12 months, the proportion with depression symptoms was 36.8 % (compared to 55 % at baseline, chi-square = 43.2, p < 0.001). Among all participants who completed 12-month questionnaires, the 12-month change in depression was −2.1 (Cohen’s d = 0.34, t = 21.5, p < 0.001) [16]. Among participants with baseline indications of depression (N = 148), the mean 12-month change in PHQ-8 depression was a decrease of 4.3 (Table 3), an effect size of 1.01.

Again as expected, when we compared the depression cohort to those with lower PHQ-8 scores, there was a statistically significant difference in changes in PHQ-8 (Table 4, row 1). The percentage of the Canada depression cohort who decreased PHQ-8 by 5 or more between baseline and 12 months was 44.6 % (Table 4, row 2). The percentage who increased by 5 or more was 4.6 %. In the non-depressed cohort of the Healthy Living Canada Study, 10.0 % decreased by 5 or more and 13.6 % increased by 5 or more.

Changes in outcome variables

For the Canadian ICDSMP depression cohort, all variables with the exception of hospitalizations had improved significantly (Table 3). For participants in Health Living Canada who had PHQ-8 scores less than 10 (no indications of depression), none of the change scores were significantly different from those of the depression cohort (Table 4). However, for each measure, the depression cohort improved as much or more than the non-depression cohort.

Twelve-month completers versus non-completers

As in the U.S. National Study, when we used intent-to-treat methodology (no change assumed for those with missing follow-up questionnaire), the p values for changes in PHQ-8 remained unchanged for the depression cohort at 12 months. The mean PHQ-8 12-month change score was reduced to from −3.40 to −3.19 for those with baseline PHQ-8 of 10 or greater. For the depression cohort, there were no significant differences at baseline in PHQ-8 depression scores for those who completed and those who failed to complete 12-month follow-up questionnaires.

Using intent-to-treat methodology within the Healthy Living Canada depression cohort, the p values for 12-month change scores for all outcomes remained unchanged. There were no significant differences at baseline between those who completed questionnaires and those who did not.

DISCUSSION

Looking at the first of the three aims of this study, we found 27 % of the U.S. National Study participants and 55 % of the Health Living Canada participants had PHQ-8 levels of 10 and above. We cannot determine why the PHQ-8 scores were much higher in the Healthy Living Canada program than in the U.S. National Study, whether it had to do with cultural differences, recruitment differences resulting in different populations, or perhaps because people with depression may be more likely to enroll in Internet-based programs. There were also large differences in the mean ages of the two sample populations (60.0 versus 46.6, respectively). Within the depression cohorts, when we compare the two studies, there are some indications that the Canadian population had poorer baseline health (more pain, more fatigue, more depression). It is beyond the scope of this study to determine the reasons for the differences between the two program populations. It is sufficient to note that the two independent implementations of the CDSMP involved quite different populations. Future study of small-group and on-line implementations within additional Canadian and U.S. populations would certainly be warranted and may have implications for recruiting people with depression.

The interventions appeared to be effective for those with indications of depression. PHQ-8 depression scores were reduced in both programs by considerable effect sizes. This has two implications. First, it is possible for a generic program aimed at multiple chronic conditions to make a clinically significant impact on at least one symptom, depression, for those who entered the program with depression. We will need further study to determine if this finding extends to other symptoms.

Secondly, it suggests a need for reexamining the policy implications of meta-analyses when applied to programs aimed at participants with multiple co-morbidities. By definition, these programs, by championing heterogeneity, decrease overall effect size for specific medical indicator measures, since not all participants will be in need of improvement for all indicators. In the future, we will need methodologies to parse the effects of such programs for populations who meet specific condition criteria such as illustrated for depression by this study.

When we compared the depressed and the non-depressed cohorts on additional health outcome variables (pain, fatigue, activity limitation, and medication adherence), the cohort with depression did at least as well if not considerably better than the participants with lower levels of PHQ-8 depression. This confirms that the programs are appropriate for participants with depression and suggests that the programs may be particularly beneficial for those with indications of depression.

Comparing the proportion who improved or got worse on PHQ-8 by a clinically significant 5 or more points, those in the depression cohort showed much higher proportions improving (46 and 45 % of the U.S. and Canadian samples, respectively), with relatively low proportions becoming more depressed (7 and 10 %). If this was merely a regression to the mean of those with higher scores, we would expect those with low baseline PHQ-8 scores to increase similarly. Instead, when we examined only the cohort with lower baseline depression, the numbers getting worse were only 8 and 14 % in the U.S. and Canadian samples. In addition, Table 4 shows that those with PHQ-8 under 10 did not have significant increases in PHQ-8 depression scores at 12 months, as might be possible if there were a regression to the mean for this chronically ill population.

Limitations

Because of the considerable differences between the populations in the two programs, we cannot address the question of whether the effects were similar for those in the small group versus the on-line intervention. Both groups showed improvements, but differences in change scores between the two groups were inconsistent. People who choose a small-group intervention as opposed to one via the Internet may have different motivations and learning styles. In addition, while both studies involved national samples, it may be that chronic disease patients living in the USA and Canada are different in multiple ways. Thus, any attempt to directly compare the two modes of delivery would not be warranted.

The two studies were both implementations and translational studies of the two respective programs, and neither were randomized studies. Thus, we have post hoc secondary subgroup analyses of longitudinal data, along with the limitation inherent to such samples. Unfortunately, the original randomized studies of the two programs [13, 14] did not include appropriate depression measures. Although indications of improvements are strong, there remains the possibility that individuals with indications of depression who did not participate in a program might have had similar improvements.

A further limitation is the use of PHQ-8 scores as indicators of depression. Although a value of 10 or greater is considered indicative of depression, it is not a clinical diagnosis of depression. In the U.S. National Study, where depression was one of the pre-listed conditions participants could report at enrollment, 59.3 % of those with PHQ-8 scores 10 or above-listed depression as one of their conditions (compared to 15.9 % of those with PHQ-8 scores below 10). PHQ-8 had a correlation of r = 0.503 with self-reported depression. Future research might examine the effects of the CDSMP on participants who self-report depression. Unfortunately, the Canadian study did not include depression as one of the listed chronic conditions that could be checked, and only 15 participants included it as one of their “other” chronic conditions. We also cannot determine if those in the U.S. National Study who listed depression as one of their conditions considered it the major reason for enrolling in the program or not.

In addition, although the 12-month follow-up rates were moderately high for dissemination studies (68 and 74 % for the two studies), we cannot be entirely sure that dropouts did not affect the change scores. Within the U.S. National Study, those who failed to complete questionnaires had only two differences at baseline from those who completed follow-up questionnaires. They were younger and had slightly more ER visits. There were no baseline differences among Healthy Living Canada participant completers and non-completers. This lack of baseline differences between questionnaire completers and “dropouts” increases the confidence in the results but does not rule out possible bias.

In summary, results from two independent translational studies suggest that both the small-group and Internet-based CDSMP appear to be appropriate and useful self-management education programs for participants with indications of depression.

Acknowledgments

This was an investigator-initiated secondary data analyses using data from two studies. The U.S. National Study was funded by the NCOA. Nancy Whitelaw was a principal investigator for the U.S. National Study and Audrey Alonis assisted with data collection and verification. The Healthy Living Canada Study was funded and administered by Alberta Health Services with software support and assistance from the NCOA. Doris Listoe of Alberta Health, Kathryn Plant at Stanford, and Jay Greenberg of NCOA were instrumental in administering and supporting the program and in collecting and managing data.

Conflict of interest

Laurent and Lorig receive royalties for the book that is used in the programs. There are no other potential conflicts of interest

Authors’ statement of and adherence to ethical standards

All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards and were approved by the IRB boards of institutions involved in the two original studies.

Footnotes

Healthy Living Canada was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT01047514, and the U.S. National study was registered as NCT01845857,

Implications

Practice: On-line and small-group generic self-management programs are effective for those with depression and should be considered for implementation as part of chronic disease management programs which include people with depression.

Policy: The Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) should be considered as an effective evidence-based program for people with depression.

Research: New methods are needed for analyzing and reporting the results of self-management programs with heterogeneous populations.

References

- 1.Corbin, Strauss . Unending work and care: managing chronic illness at home. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavard JA, Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Prevalence of depression in adults with diabetes: an epidemiological evaluation. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(8):1167–1178. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.8.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egede LE. Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunn J, Ayton DR, Densley K, et al. The association between chronic illness, multimorbidity and depressive symptoms in an Australian primary care cohort. Soc Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2012;47(2):175–184. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0330-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanners M, Barton C. Depression in the context of chronic and multiple chronic illnesses. In: Olisah V, editor. Essential notes in psychiatry. Rijeka: InTech; 2012. pp. 535–546. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grenard JL, Munjas BA, Adams JL, et al. Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic diseases in the United States: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1175–1182. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1704-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiMatteo M, Lepper HS, et al. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu SF, Huang YC, Lee MC, Wang TJ, Tung HH, Wu MP. Self-efficacy, self-care behavior, anxiety, and depression in Taiwanese with type 2 diabetes: a cross-section survey. Nurs Health Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1111/nhs.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maddux JE, Meeier LJ. Self-efficacy and depression. In: Maddux JE, editor. Self-efficacy, adaptation, and adjustment: theory, research, and application. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 141–169. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeves D, Kennedy A, Fullwood C, et al. Predicting who will benefit from an expert patients programme self-management course. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:198–201. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X277320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritter PL, Lee J, Lorig K. Moderators of chronic disease self-management programs: who benefits? Chronic Illn. 2011;7(2):162–172. doi: 10.1177/1742395311399127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ory MG, Ahn S, Jiang L, et al. National study of chronic disease self-management: six month outcome findings. J Aging Health. 2013;25(7):1258–1274. doi: 10.1177/0898264313502531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorig K, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Plant K. Internet-based chronic disease self-management: a randomized trial. Med Care. 2006;44(11):964–971. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000233678.80203.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorig K, Laurent DD, Laurent DD, Plant K, Krishna E, Ritter PL. The components of action planning and their associations with behavior and health outcomes. Chronic Illn. 2014;10(1):50–59. doi: 10.1177/1742395313495572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Stewart AL, Sobel DS, Brown BW, Bandura A. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39(11):1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, González VM. Hispanic chronic disease self-management: a randomized community-based outcome trial. Nurs Res. 2003;52(6):361–369. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dongbo F, Hua F, McGowan P, et al. Implementation and quantitative evaluation of chronic disease self-management program in Shanghai, China: randomized controlled trial. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:174–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swerissen H, Belfrage J, Weeks A, et al. A randomized control trial of a self-management program for people with a chronic illness from Vietnamese, Chinese, Italian and Greek backgrounds. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths C, Motlib J, Azad A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a lay-led self-management program for Bangladeshi patients with chronic disease. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:831–837. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goeppinger J, Armstrong B, Schwartz T, Ensley D, Brady TJ. Self-management education for persons with arthritis managing comorbidity and eliminating health disparities. Arthritis Care Res. 2007;57:1081–1088. doi: 10.1002/art.22896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy A, Reeves D, Bower P, et al. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a national lay-led self care support programme for patients with long-term conditions: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:254–261. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Dost A, et al. The South Australia health chronic disease self-management internet trial. Health Educ Behav. 2012;40(1):67–77. doi: 10.1177/1090198112436969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Dost A, Plant K, Laurent DD, McNeil I. The expert patients programme online, a 1-year study of an Internet-based self-management programme for people with long-term conditions. Chronic Illn. 2008;4:247–256. doi: 10.1177/1742395308098886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Self-efficacy, the exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Patient Health Questionnaire Study Group. Validity and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spritzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9, validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spritzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1–3):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Razykov I, Ziegelstein RC, Whooley MA, Thombs BD. The PHQ-9 versus the PHQ-8—is item 9 useful for assessing suicide risk in coronary artery disease patients? Data from the Heart and Soul Study. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73(3):163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32(9):1–7. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells TS, Horton JL, LeardMann CA, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ. A comparison of the PRIME-MD PHQ-9 and PHQ-8 in a large military prospective study, the Millennium Cohort Study. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritter P, González V, Laurent DD, Lorig KR. Measurement of pain using the visual numeric scale. J Rheumatol. 2006;44(11):964–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dixon J, Bird H. Reproducibility along a 10-cm vertical visual analogue scale. Ann Rheum Dis. 1981;40:87–89. doi: 10.1136/ard.40.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorig K, Stewart A, Ritter P, González V, Laurent D, Lynch J. Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986; 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Ritter PL, Stewart AL, Kaymaz H, Sobel DS, Block DA, Lorig KR. Self-reports of health. [DOI] [PubMed]