ABSTRACT

Adherence to prescribed medications continues to be a problem in the treatment of chronic disease. Motivational interviewing (MI) has been shown to be successful for eliciting patients’ motivations to change their medication-taking behaviors. Due to the constraints of the US healthcare system, patients do not always have in-person access to providers. Because of this, there is increasing use of non-traditional healthcare delivery methods such as telephonic counseling. A systematic review was conducted among published studies of telephone-based MI interventions aimed at improving the health behavior change target of medication adherence. The goals of this review were to (1) examine and describe evidence and gaps in the literature for telephonically delivered MI interventions for medication adherence and (2) discuss the implications of the findings for research and practice. The MEDLINE, CINAHL, psycINFO, psycARTICLES, Academic Search Premier, Alt HealthWatch, Health Source: Consumer Edition, and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition databases were searched for peer-reviewed research publications between 1991 and October 2012. A total of nine articles were retained for review. The quality of the studies and the interventions varied significantly, which precluded making definitive conclusions but findings among a majority of retained studies suggest that telephone-based MI may help improve medication adherence. The included studies provided promising results and justification for continued exploration in the provision of MI via telephone encounters. Future research is needed to address gaps in the current literature but the results suggest that MI may be an efficient option for healthcare professionals seeking an evidence-based method to reach remote or inaccessible patients to help them improve their medication adherence.

Keywords: Motivational interviewing, Medication adherence, Telephonic, Behavior change

INTRODUCTION

Medication non-adherence continues to be a problem in the treatment of chronic disease [1]. In the US, for example, studies have shown that only 51 % of patients with hypertension adhere to treatment regimens [1]. Non-adherence can lead to increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs [1]. Improving patient adherence to medication regimens can improve clinical outcomes and decrease consumption of medical resources. Patients may be non-adherent to medication regimens for various reasons that may include aversion to medications and/or their side effects, cost, and limited access, among others; therefore, an intervention tailored to meet each patient’s needs or access may be likely to impact a person’s adherence decision-making.

Healthcare settings in today’s environment leave providers with limited patient contact time [2, 3]. Because of this, efficient means of delivery of medication adherence interventions are being studied. An additional concern is that persons who live in areas with access barriers to healthcare providers, including those in rural, underserved parts of the US, do not have opportunities to be exposed to health behavior education and change interventions, and may be more at risk of medication non-adherence. To address provider time limits and patient access limits, non-traditional methods that engage telephonic contact and/or technology are being explored for potential as efficient methods for delivering tailored medication adherence communication strategies to those who may need it most.

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a tailored, patient-centered communication skills set that has been shown to have a significant impact on a broad range of health behavior change targets and patient populations, including medication adherence [4]. With its origins in counseling for substance abuse and addiction treatment, MI works by supporting a patient’s autonomy and by activating his/her own internal motivation for change or adherence to treatment [5]. The communication principles and skills of MI are applied in a collaborative, caring, nonjudgmental interview so that the patient ends up making the argument for the target change. Through brief patient-centered interactions, providers using MI can help patients explore and resolve their ambivalence regarding a specific behavior change [5]. The most recent (2014) American Diabetes Association practice recommendations include an emphasis on using patient-centered communication like motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing has been examined and studied for its potential as a medication adherence intervention in pharmacy, healthcare settings, and in disease-specific interventions [6–9].

Examples of non-traditional delivery methods in which MI is being explored include telephone, group format, computerized, and paper- or print-based self-help manuals [9]. It would be useful to examine the evidence and gaps in reported research to describe the potential for impact of MI on medication adherence when provided via non-traditional delivery methods that have been proposed for use with populations that have limited access to care.

Telephone counseling is attractive because it is less expensive compared to in-person counseling, it is convenient, it allows a sense of anonymity, and it gives the participant a sense of control [10]. It is also believed that telephone-provided counseling can increase access to underserved populations, such as rural populations and those with low socioeconomic status [10]. In addition, telephone counseling in general has been shown to be effective for reduction of tobacco use and for nicotine therapy [11, 12], increased mammogram use [13], and physical activity in older people [14], to name a few. While the movement to telehealth delivered by more advanced technology than telephones is progressing, persons in remote areas may be more inclined to have and use a telephone than more complex high-tech devices.

Based on what we know about MI as an intervention and on what has been demonstrated in the literature regarding the efficiency and effectiveness of telephone-based counseling, exploring the evidence and gaps in the literature related to MI as a medication adherence intervention delivered by telephone would be an important contribution, particularly when considering effective and efficient means for reaching persons with limited access to care and adherence interventions. Although some practitioners and case managers are using MI as a telephone intervention, no systematic assessment of evidence and gaps in the literature has been conducted to date. This report describes a systematic review of telephone-based MI interventions aimed at improving the health behavior change target, medication adherence. The goals of this review were to examine and describe evidence and gaps in the literature for telephonically delivered MI interventions for medication adherence and to discuss practice implications of the findings.

METHODS

A modified Cochrane method was used to conduct a systematic search and review of peer-reviewed journal articles relevant to telephonically delivered MI interventions for medication adherence. The modified Cochrane systematic approach included an a priori identification of a specific intervention (MI delivered telephonically), specific outcome (change for the target behavior, medication adherence), population (adults with any chronic condition requiring medication), and study design (any rigorous study designs, with randomized controlled trials having first priority in the first search tier). The traditional Cochrane method was modified in that the Cochrane systematic search and review methods were applied to a more exploratory research question regarding descriptive evidence and gaps in the literature instead of a narrow and specific research question that is often seen in Cochrane reviews. The search was conducted among relevant databases, including MEDLINE, CINAHL, psycINFO, psycARTICLES, Academic Search Premier, Alt HealthWatch, Health Source: Consumer Edition, and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition. Search terms included were motivational interviewing (i.e., motivational interviewing OR motivational enhancement therapy OR MI), adherence (i.e., adherence OR compliance OR medication adherence), and telephone (i.e., telephone OR telephonic OR telehealth OR telecommunication). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the search tiers.

The time frame between January 1991 and October 2012 was used because the development and description of MI were not widely published prior to the early 1990s. Opinion articles, reviews, and articles not published in the English language were excluded. Both investigators evaluated the search results. Articles were included for full text review based on search tiers that first included title and abstract review from the results of searches among the previously listed databases; this tier also included hand searches for relevant articles cited in reference lists of reviews and relevant articles. The subsequent search tier included intention to screen first for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and then evolved to the next tier for other rigorous study designs. If there was any discrepancy between reviewers regarding the inclusion of a study, consensus was reached through discussion.

When a systematic review is conducted among published peer reviewed papers, it is important to evaluate the quality of the study designs/reports before describing any evidence summary or drawing conclusions among suggested results. While there are several study “grading” systems commonly used and reported among published systematic reviews, the authors of this report chose to use the Cochrane Collaboration method that assesses risk of bias among studies [15]. In describing a summary of evidence in the literature, or in drawing conclusions from the results of retained literature, it is important to consider how level of bias risk resulting from study design flaws or limitations may influence these descriptions and/or conclusions. The Cochrane system includes provision to examine and assign levels of risk based on important study design factors including randomization methods (if any) and sample size, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and practitioners to intervention and outcome, completion level of outcome data, and treatment fidelity. It is clear that behavior change interventions, because of their interactive nature and design, can rarely be considered without some level of bias from characteristics like blinding or concealment, since delivery of an MI intervention requires a well-trained and intentional practitioner.

RESULTS

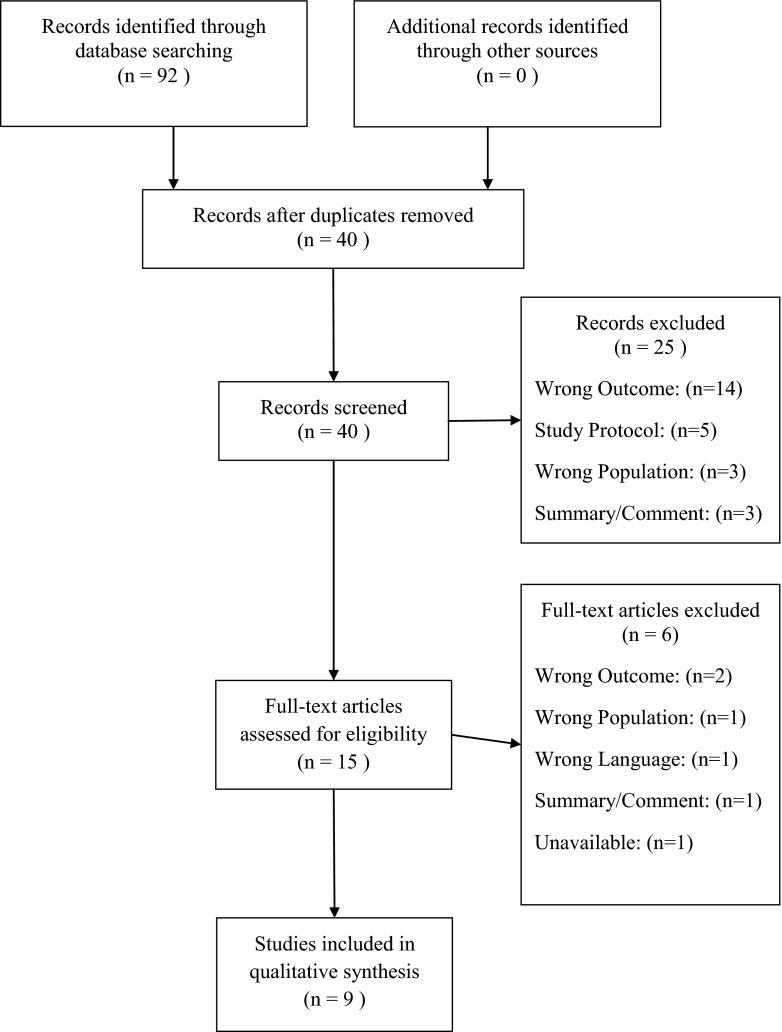

The inclusion of studies across search tiers is depicted in the trial flow diagram (Fig. 1). The final tier resulted in 15 full-text articles that were fully assessed for eligibility; six being excluded for wrong outcome (n = 2),wrong population (n = 1), wrong language (n = 1),wrong publication type (n = 1), or were unavailable/not peer-reviewed (n = 1). A total of nine articles were retained for review of their contribution to the evidence (or gaps) regarding telephonic MI interventions and its impact on the target behavior outcome, medication adherence. Due to the heterogeneity of diseases and their relevant clinical indicators in the retained studies, and since not all retained studies examined clinical indicators, clinical outcomes were not reported or analyzed within the scope of this paper.

Fig 1.

Trial flow diagram

Risk of bias in each of the included studies was evaluated using a modified form of the Cochrane [15] tool for assessing risk of bias; the tool’s factors and applications to the retained studies are summarized in Table 1. Four articles were RCTs and five were cohort studies. Among the nine retained articles, two studies had the lowest potential risk of bias while four were assessed as having a higher potential risk of bias compared to the group as a whole. Allocation concealment and blinding are not common among the retained studies, and study samples varied in size from more than 2,000 at the beginning of one study to less than 40 at the end of another. Fidelity of the MI intervention was explicitly assessed in five of the nine retained studies.

Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment for included studies (modified from Cochrane method)

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Treatment fidelity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berger, 2005 | ? | ? | − | + | − | − |

| Cook, 2007 | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Cook, 2008 | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Cook, 2009 | − | − | − | − | ? | + |

| Cook, 2010 | − | − | − | − | ? | + |

| Konkle-Parker, 2012 | ? | ? | ? | − | ? | + |

| Lawrence, 2008 | − | − | + | + | + | ? |

| Solomon, 2012 | + | ? | + | + | + | + |

| Williams, 2012 | ? | + | + | ? | + | + |

+ Low risk of bias in study design

− High risk of bias in study design

? Unclear or insufficient detail

The retained studies examined telephone delivered motivational interviewing interventions and their impact on medication adherence for the treatment of HIV (n = 2), osteoporosis (n = 2), cardiovascular disease and/or diabetes (n = 1), kidney disease and diabetes (n = 1), ulcerative colitis (n = 1), mental illness (n = 1), and multiple sclerosis (n = 1).

Intervention

Study designs were heterogeneous regarding the number of counseling sessions and design of the telephone intervention itself. The design of the intervention can be classified into categories: (1) in-person and telephone delivered MI, (2) telephone delivered MI with educational materials, and (3) telephone delivered MI with cognitive–behavioral techniques. Table 2 summarizes the designs of the interventions utilized in the retained studies. In the four studies conducted by Cook and associates [16–19], a program was used that facilitated semi-structured telephonic MI counseling to improve medication adherence; therefore, the intervention for these four retained studies is nearly identical but is applied across different diseases/conditions. The other retained studies had vastly different interventions, including reported number of telephone counseling sessions which ranged from one to ten over the duration of 3 to 17 months. In addition, the number of follow-ups to evaluate medication adherence ranged from one to three.

Table 2.

Disease, duration, intervention training, and outcome measures

| First author, year | Disease | Duration (months) | Study design | Intervention | MI training | Outcome measures of adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berger, 2005 | Multiple Sclerosis | 3 | RCT | I: Software based on MI and transtheoretical model of change guided telephone counseling provided by one of three counselors every 2 to 4 weeks C: Standard care |

8 h of MI-based software training | Discontinuation of Avonex treatment |

| Cook, 2007 | Osteoporosis | 4.1 | Cohort Study | I: Telephonic counseling delivered by one of four RNs trained in MI and cognitive-behavioral techniques • At-risk patients received a median of five contacts • Low-risk patients received a median of three contacts C: N/A |

No explanation of training | Self-reported adherence Pharmacy Rx fills |

| Cook, 2008 | Mental Illness | 6 | Cohort Study | I: Telephonic counseling delivered by one of three RNs trained in MI and cognitive-behavioral techniques • At-risk patients received an average of 3.5 calls • Average length of 11 min • Low-risk patients received one call at 6 months; also toll-free number for at-will contacts C: N/A |

8 h of training on the counseling model | Self-reported adherence Pharmacy Rx fills Emergency department utilization |

| Cook, 2009 | HIV | 6 | Cohort Study | I: Telephonic counseling delivered by RNs trained in MI and cognitive-behavioral techniques • High-risk patients received a median of 3 calls • Average length of 7.5 min • Low-risk patients received one call at 6 months C: N/A |

8 h of training on the counseling model | Self-reported adherence |

| Cook, 2010 | Ulcerative Colitis | 6 | Cohort Study | I: Telephonic counseling delivered by RNs trained in MI and cognitive-behavioral techniques • High-risk patients received multiple calls from the same RN • Low-risk patient received one call at 6 months • All patients received a toll-free number to call with any questions C: N/A |

8 h of training on the counseling model | Self-reported adherence |

| Konkle-Parker, 2012 | HIV | 6 | RCT | I: In-person MI sessions at weeks one and two • Lasted 30–60 min Telephone MI sessions at weeks 3, 4, 6, 10, 16, and 24. • Lasted less than 10 min $10 incentive paid for in-person sessions C: Usual care |

18 h of training from MINTa trainer and practice | Self-reported adherence Pharmacy Rx refill rate |

| Lawrence, 2008 | Cardiovascular Disease and/or Diabetes | 17 | Cohort Study | I: Care managers call patient when software indicated an Rx filled within 120 days that was 60+ days late • MI, active listening, and health behavior change techniques used to address patients’ readiness to change behaviors related to adherence |

No explanation of training | Refill re-initiation Time to therapy reinitiation |

| Solomon, 2012 | Osteoporosis | 12 | RCT | I: MI delivered by one of seven health educators • Aim was ten sessions per patient • seven mailings covering exercise, fall prevention, and recommended calcium intake C: seven mailings covering exercise, fall prevention, and recommended calcium intake |

Half day of training from MI expert | Medication Possession Ratio |

| Williams, 2012 | Kidney Disease and Diabetes | 3 | RCT | I: MI delivered by nurse every 14 days • Used standing script and checklist • Self-monitoring of BP, medication review, 20 min DVD C: Usual care |

No explanation of training | Pill counts Morisky scale |

I Intervention group; C control group

aMotivational Interviewing Network of Trainers

Adherence

Table 2 shows the source of data and various measurements of adherence utilized in the included studies. Medication adherence was measured using patient self-report (n = 7) and health plan or pharmacy claims data (n = 5). Three studies used both patient self-reported adherence and pharmacy claims data. In the studies that utilized patient self-report of medication adherence, one used pill counts and the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale, one used a 3–4 week recall by visual analog scale during an in-person visit, and five assessed medication adherence through questions, such as, “how many days in the last week have you taken your medication as prescribed.” In the studies that utilized health plan or pharmacy claims data, one used medication possession ratio, one measured time from intervention to prescription refill, and three used the number of refills and prescription fill dates obtained from pharmacies. In the three studies that utilized both patient self-reported adherence and health plan or pharmacy claims data, two found agreement between measures. The remaining study that utilized both measures did not report correlation between measures.

Table 3 shows the number of participants included in each study and the results of the MI intervention on the medication adherence outcome measures. Six of the nine studies reported statistically significant differences between intervention and control groups for change in adherence. Five of these were cohort studies and one was a RCT. One study, conducted by Berger and associates [20], looked at the adherence problem from the perspective of reduction in non-adherence for a treatment commonly abandoned by patients due to unpleasant side effects; they found that telephonic MI intervention resulted in 1.2 % of patients in the treatment arm discontinuing use of Avonex injections for their multiple sclerosis while those in the control arm discontinued Avonex at a rate of 8.7 % (P = 0.001). A study conducted by Cook and associates [16] in patients with osteoporosis showed that adherence to medication was significantly higher than the population base rate after 3 months (76.7 vs. 67.5 %; P = 0.007) and after 6 months (68.8 vs. 40.5 %; P = 0.009); they also had better adherence than those who were referred to the study but did not participate at 6 months (69 vs. 63 %) although this difference was not significant (P = 0.06). Another study by Cook and associates [17] found adherence to medications for mental illness in the group that received the MI telephone intervention was significantly higher at 6 months than the comparison group in both the pharmacy claims analysis (48 vs. 26 %; P = 0.004) and the self-report analysis (50 vs. 26 %; P = 0.002). In a third study conducted by Cook and associates [18], the percentage of HIV+ participants who were 95 % or more adherent with their antiretroviral therapy regimen was significantly higher than the expected rate of 50 % based on previous literature (P = 0.001). A fourth study conducted by Cook and associates [19] found significantly higher adherence to medications for ulcerative colitis in the nurse-delivered treatment arm compared to the expected level of adherence (57 vs. 88 %; P < 0.001). In the study conducted by Lawrence and associates [21], the patients in the intervention arm had significantly higher reinitiation of overdue medications after an MI-based telephone encounter compared to patients in the control group (59.3 vs. 42.1 %; P < 0.05) and significantly shorter amount of time to reinitiation (59.5 vs. 107.4 days; P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Participants and results

| First author, year | Study participants: N (%) | Results for medication adherence outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Berger, 2005 | I: 172 (46.9) C: 195 (53.1) |

Discontinuation of Avonex: 1.2 % (I) vs. 8.7 % (C)** |

| Cook, 2007 | I: 402 C: National Baseline Data |

Self-reported adherence: Month 3: 81.8 % (I) vs. 67.5 % (C)** Month 6: 69.8 % (I) vs. 40.5 % (C)** Pharmacy Rx fills: Month 3: 76.7 % (I) vs. 67.5 % (C)** Month 6: 68.8 % (I) vs. 40.5 % (C)** |

| Cook, 2008 | I: 51 (25.2) C: 151 (74.8) |

Self-reported adherence: Month 3: 79 % (I) vs. 36 % (C)** Month 6: 50 % (I) vs. 26 % (C)** Pharmacy Rx fills: Month 3: 59 % (I) vs. 36 % (C)** Month 6: 48 % (I) vs. 26 % (C)** Mean Emergency Department visits per person: 1.11 (I) vs. 5.03 (C)** |

| Cook, 2009 | I: 41 C: Expected Rate |

Self-reported adherence: Month 6: 76 % (I) vs. 50 % (C)** |

| Cook, 2010 | I: 135 C: Expected Rate |

Self-reported adherence: Month 6: 88 % (I) vs. 57 % (C)** |

| Konkle-Parker, 2012 | I: 22 (61.1) C: 14 (39.9) |

Self-reported adherence by recall: 86 % (I) vs. 87 % (C) Pharmacy Rx refill rate: 0.93 (I) vs. 0.92 (C) |

| Lawrence, 2008 | I: 94 (60.6) C: 61 (39.4) |

Refill reinitiation: 59.3 % (I) vs. 42.1 % (C)* Time to therapy reinitiation 59.5 days (I) vs. 107.4 days (C) * |

| Solomon, 2012 | I: 1,046 (50.1) C: 1,041 (49.9) |

Medication Possession Ratio: 49 % (I) vs. 41 % (C) Medication Possession Ratio improvement by Age: Aged 65–74: 48 % (I) vs. 31 % (C)* Aged 75 or older: 49 % (I) vs. 46 % (C) |

| Williams, 2012 | I: 36 (48.0) C: 39 (52.0) |

Pill counts: 66 % (I) vs. 58.4 % (C) Morisky scale: Forget to take medicines: 63.9 % (I) vs. 64.1 % (C) Problems remembering: 66.7 % (I) vs. 64.1 % (C) Sometimes stop taking: 91.7 % (I) vs. 100 % (C) Stop because feel worse: 94.4 % (I) vs. 94.9 % (C) |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

I Intervention, C Control

The three studies that reported no statistically significant differences between treatment and control groups were RCTs. Solomon and associates [22] showed an improvement in adherence to osteoporosis medications based on medication possession ratio in the intervention group compared to the control group (49 vs. 41 %), but this difference was not significant (P = 0.07). Subgroup analyses in the study found significant differences in adherence to osteoporosis medications between groups aged 65–74 years (intervention group median adherence, 48 % and control group median adherence, 31 %) compared with little difference in the group aged 75 or older (intervention group median adherence, 49 % and control group median adherence, 46 %; P = 0.045). Williams and associates [23] found no significant difference when using pill counts to determine adherence to medications for blood pressure control between the intervention group and control group (66 vs. 58.4 %; P = 0.162). Konkle-Parker and associates [24] reported no significant differences between intervention and control groups in terms of HIV medication adherence.

DISCUSSION

Although the quality of the studies and the interventions varied as noted in the Cochrane quality assessment, the results across studies suggest some support for potential use of telephone-delivered motivational interviewing, but it is clear that further research is warranted due to quality concerns and heterogeneity among retained studies in this review. No one intervention protocol seemed to stand out in terms of optimal number or type of calls. Overall, the majority (five of nine) of studies found that MI can be effective in increasing medication adherence when provided telephonically. While the studies retained in this review did not specify geographic location of their participants, it can be assumed that telephone-based MI could be used to reach persons who may otherwise have access challenges (i.e., rural, inner city, and home-bound). Additionally, the findings suggest that the results from the retained studies may contribute to the MI literature that has shown positive impact on medication adherence.

The heterogeneity of the interventions and of the measurements of adherence among the studies included is a limitation for drawing definitive conclusions from this review. Some of the studies used MI combined with cognitive-behavioral techniques or other psychological techniques that may have influenced the increased medication adherence in those studies [16–20]. Although this is a possibility, these studies were included in this review because MI-trained practitioners commonly also have knowledge and training in other counseling techniques, and MI itself is founded from concepts across theories of psychotherapy and behavior change. As for the measurements of adherence, patient self-reported adherence tends to be over-estimated while claims data is often used as a proxy for adherence and true adherence to medications is not measured. This suggests that validated measures of medication adherence are also seen as beneficial. Only one of the included studies used a validated and widely recognized measure of adherence and therefore high adherence rates in some studies may be misleading.

The low number of randomized controlled trials and the weak results of the few included may also be considered cause for concern. Of the four randomized controlled trials, three did not find a significant impact of motivational interviewing on medication adherence. Two of these studies were conducted with very small sample sizes (n < 40 in intervention group) for which the investigators expressed concern [23, 24]. Both demonstrated improvements in adherence but the differences were not statistically significant. The third article reported a subgroup analysis that found significant improvements in patients aged 60–75 years compared to those older than 75 years. This raises a concern that further study is needed regarding possible differences in the effect of MI or other factors across age groups. Additional randomized controlled trials powered with larger sample sizes may be more likely to show significant improvements in adherence to medications among appropriate age groups from MI-based telephone interventions.

In addition, the majority of retained studies experienced very high attrition rates which is not uncommon when conducting behavior intervention research in chronic conditions that require follow-up over an extended period of time. The use of health plan and pharmacy claims data can allow for longitudinal analysis in situations where patients are likely to be lost to follow-up. The use of incentives when patient self-report is necessary may also encourage continued participation from study subjects.

Another important gap in the retained studies was the lack of a description of the MI training the providers received. Few studies detailed the type or length of MI training, where the training was provided, by whom the training was provided, and assessment of fidelity for MI in the intervention. A review of training in MI conducted by Madson and associates [25] suggests that this is cause for concern when evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention because it is not clear that the MI being provided is consistent with established MI principles and methods. While there is no “gold standard” for time required or methods of MI training, it is widely accepted that MI cannot be mastered overnight. Only one of the studies reported the MI training of interventionists in sufficient detail. This makes it difficult to fully claim that the results of the included studies were caused by MI alone or may have been contributed to by other outside factors.

Limitations

Several limitations are present in this review despite the methods intended to achieve valid and reliable results. First, only studies published in English were included for analysis introducing bias towards these studies. The researchers only know of one study [26] that was excluded due to this but others may have been as well. Second, the literature search and the initial inclusion/exclusion tiers were conducted by one researcher. This could have introduced judgment bias and possibly distorted the results. To minimize such distortion, both researchers worked together in subsequent tiers of inclusion/exclusion of studies. Another limitation is the inclusion of non-randomized trials in self-selected convenience samples; this introduces the potential for selection bias. Adherence rates have been shown to be higher among those who choose to participate in a study without incentive. The researchers believe that the rigorous designs of the retained studies minimized this potential risk of bias. Finally, it is difficult to compare adherence to medications between such diverse diseases as HIV and type 2 diabetes, among others. This review included studies across heterogeneous diseases which may vary regarding motivations for adherence. Results should be evaluated with this in mind.

Implications for practice

Overall, the studies included in this review suggest that motivational interviewing, when appropriately trained and applied, may be effective at increasing adherence to medication regimens when provided telephonically. Motivational issues can greatly impact patient behavior. MI can help patients elicit their own needed internal motivation to make health behavior changes, like medication adherence, that can result in positive health outcomes. Additional research is needed to explore potential business models for the provision of telephonic MI for medication adherence, including the economic impact of the intervention.

Implications for research

The results of this systematic review demonstrate the need for future research in telephone-delivered motivational interviewing to improve medication adherence. Included studies, despite heterogeneity in design and adherence measures as well as MI training of providers, exhibited results that support the assertion that continued exploration in the provision of MI via telephone is warranted. Also, the range of chronic diseases under investigation in the studies of MI’s impact on medication adherence suggests MI should be further studied in rigorous designs with similar disease-to-adherence motivational factors taken into consideration. Future studies should describe the MI training providers received and how treatment fidelity was evaluated throughout the study. Additional research, using rigorous study designs in actual practice situations, is needed; utilizing health plan or pharmacy claims data to assess medication adherence among the chronically ill across specific diseases or conditions will also be an important contribution to this body of work.

CONCLUSION

The effect of a telephonically-delivered MI intervention on medication adherence may be promising as an efficient means of delivering an evidence-based communication skills strategy, but additional research is warranted using rigorous study designs and adequately trained MI providers. Although there have been studies that demonstrate MI’s feasibility and effectiveness, they are not without flaws. Randomized-controlled trials that evaluate the effectiveness of MI in actual practice settings and situations are needed. MI is a potential option for healthcare professionals looking for a method to help patients decide to improve their medication adherence as well as for researchers evaluating the impact of behavior interventions on outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

All authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Motivational interviewing may be effective at increasing adherence to medication regimens when provided telephonically.

Policy: Research funding for interventions that have the ability to reach populations that do not have access to in-person providers is crucial to improve patient and public health.

Research: Future research should describe the motivational interviewing training that providers received, how treatment fidelity was evaluated throughout the study, and employ rigorous study designs that utilize health plan or pharmacy claims data to assess medication adherence among the chronically ill across specific diseases or conditions.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braddock CH, 3rd, Snyder L. The doctor will see you shortly. The ethical significance of time for the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1057–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dugdale DC, Epstein R, Pantilat SZ. Time and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(Suppl 1):S34–S40. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kavookjian J. Motivational interviewing. In: Richardson M, Chant C, Chessman KH, Finks SW, Hemstreet BA, Hume AL, editors. Pharmacotherapy self-assessment program. 7. Lenexa, KS: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2011. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler C. Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill S, Kavookjian J. Motivational interviewing as a behavioral intervention to increase HAART adherence in patients who are HIV+: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Care. 2012;24(5):583–592. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Possidente CJ, Bucci KK, McClain WJ. Motivational interviewing: a tool to increase medication adherence. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1311–1314. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM. Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reese RJ, Conoley CW, Brossart BF. Effectiveness of telephone counseling: a field-based investigation. J Couns Psychol. 2002;49(2):233–242. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.49.2.233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swartz SH, Cowan TM, Klayman JE, Welton MBT, Leonard BA. Use and effectiveness of tobacco telephone counseling and nicotine therapy in Maine. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu SH, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, et al. Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(14):1087–1093. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoddard AM, Fox SA, Costanza ME, et al. Effectiveness of telephone counseling for mammography: Results from five randomized trials. Prev Med. 2002;34(1):90–99. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolt GS, Schofield GM, Kerse N, Garrett N, Oliver M. Effect of telephone counseling on physical activity for low‐active older people in primary care: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(7):986–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

- 16.Cook PF, Emiliozzi S, McCabe MM. Telephone counseling to improve osteoporosis treatment adherence: an effectiveness study in community practice settings. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22(6):445–456. doi: 10.1177/1062860607307990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook PF, Emiliozzi S, Waters C, El Hajj D. Effects of telephone counseling on antipsychotic adherence and emergency department utilization. Am J Manage Care. 2008;14(12):841–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cook PF, McCabe MM, Emiliozzi S, Pointer L. Telephone nurse counseling improves HIV medication adherence: an effectiveness study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(4):316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook PF, Emiliozzi S, El-Hajj D, McCabe MM. Telephone nurse counseling for medication adherence in ulcerative colitis: a preliminary study. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81(2):182–186. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger BA, Liang H, Hudmon KS. Evaluation of software-based telephone counseling to enhance medication persistency among patients with multiple sclerosis. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2005;45(4):466–472. doi: 10.1331/1544345054475469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrence DB, Allison W, Chen JC, Demand M. Improving medication adherence with a targeted, technology-driven disease management intervention. Dis Manag. 2008;11(3):141–144. doi: 10.1089/dis.2007.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon DH, Iversen MD, Avorn J, et al. Osteoporosis telephonic intervention to improve medication regimen adherence: a large, pragmatic, randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(6):477–483. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams A, Manias E, Walker R, Gorelik A. A multifactorial intervention to improve blood pressure control in co-existing diabetes and kidney disease: a feasibility randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(11):2515–2525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konkle-Parker DJ, Erlen JA, Dubbert PM, May W. Pilot testing of an HIV medication adherence intervention in a public clinic in the Deep South. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2012;24(8):488–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2012.00712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madson MB, Loignon AC, Lane C. Training in motivational interviewing: a systematic review. J Subst Abus Treat. 2009;36(1):101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lange I, Campos S, Urrutia M, et al. Effect of a tele-care model on self-management and metabolic control among patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care centers in Santiago, Chile. Rev Med Chil. 2010;138(6):729–737. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872010000600010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]