Abstract

One barrier to searching for novel mutations in African American families with breast cancer is the challenge of effectively recruiting families—affected and non-affected relatives—into genetic research studies. Using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) orientation, we incorporated several evidence-based approaches through an iterative fashion to recruit for a breast cancer genetic epidemiology study in African Americans. Our combined methods allowed us to successfully recruit 341 African American women (247 with breast cancer and 94 relatives without breast cancer) from 127 families. Twenty-nine percent of participants were recruited through National Witness Project (NWP) sites, 11 % came from in-person encounters by NWP members, 34 % from the Love Army of Women, 24 % from previous epidemiologic studies, and 2 % from a support group. In terms of demographics, our varied recruitment methods/sources yielded samples of African American women that differ in terms of several sociodemographic factors such as education, smoking, and BMI, as well as family size. To successfully recruit African American families into epidemiological research, investigators should include community members in the recruitment processes, be flexible in the adoption of multipronged, iterative methods, and provide clear communication strategies about the underlying benefit to potential participants. Our results enhance our understanding of potential benefits and challenges associated with various recruitment methods. We offer a template for the design of future studies and suggest that generalizability may be better achieved by using multipronged approaches.

Keywords: African American, Genetic epidemiology, Community-based participatory research (CBPR), Breast cancer

Introduction

Not only are African Americans historically under-represented in scientific research, but due to lack of engagement in the power structure influencing discovery decisions, they are also seldom in a position to direct research focused on the problems and issues that directly impact their health (Durant et al. 2007; Hughes et al. 2004). Accelerating the nation’s cancer disparities research agenda requires opportunities that allow target audience members to provide significant input about the science and methods as well as proposed solutions (e.g., interventions) to address disparities (Israel et al. 2005; Minkler and Wallerstein 2012).

In 2008, an African American woman in Buffalo, NY (VMR), asked, “Why? What is the gene that is affecting MY family?” She had had eight other family members diagnosed with breast cancer and she herself tested BRCA negative. This led to an innovative community-based participatory research (CBPR) collaboration between a genetic epidemiologist (HO-B), a national organization of African American breast cancer advocates (The National Witness Project®), and a 3-year recruitment effort (Ochs-Balcom et al. 2011). The resulting breast cancer genetic epidemiology study, “The Jewels in Our Genes study,” was designed to search for novel genetic loci associated with breast cancer in African American pedigrees. Our study was the first of its kind; reasons for this include challenges of identification and access to appropriate families, failure to recruit adequate sample sizes, and failure of inclusion of this audience and these patients in the scientific discovery process (Johnson et al. 2011; Murphy and Thompson 2009).

The methodological objective of our study was to develop an efficient method to identify and recruit within 3 years approximately 340 participants (African American women diagnosed with cancer as well as their affected and non-affected kin) from a minimum of 125 families nationally, for participation in this genetic study. Herein, we report the process and results of our recruitment efforts as developed and operationalized within our academic-community research partnership. The resulting multilevel, iterative process—a key element of CBPR (Israel et al. 2005)—was essential for effective recruitment.

Methods

As published previously (Ochs-Balcom et al. 2011), we utilized a partnership with the National Witness Project (NWP), a culturally competent, community-based breast and cervical cancer education program designed to meet the specific cultural, spiritual, and learning styles of African American women (Erwin et al. 1992; Hurd et al. 2003). The NWP helped to design materials, develop the study name (The Jewels in Our Genes study), study logo, the initial recruitment strategy, and specific plans for data collection. These materials and plans were developed through formative research involving African American breast cancer survivor/advocates and their relatives (Ochs-Balcom et al. 2011). Our initial recruitment plan was to focus on families who could be located within and through the NWP. African American women ever diagnosed with breast cancer with at least one living blood relative also diagnosed with breast cancer were recruited along with their older unaffected siblings, where available. Women who were carriers of BRCA mutations were not eligible. The study was approved by the University at Buffalo Institutional Review Board (IRB).

The academic partners (HO-B, DOE, LJ) had established collaborations with three studies involving African American breast cancer patients (Ambrosone et al. 2009; Thompson and Li 2012; Thompson et al. 2012) in the hopes that previous participation would result in women being open to participation in our family-based study. With a focus on those with a family history of breast cancer and who agreed to be contacted for future studies, we obtained permissions/IRB approvals at all partnering institutions to allow for contact with these women via mailing.

Our NWP/WP community partners (who were also members of our study team, VMR, MJW, DJ) attended various selected national conferences and events (e.g., breast cancer race/walks and conferences) to recruit. Events were selected to have a high proportion of potentially eligible women (i.e., African American breast cancer survivors) and table space was either arranged or purchased. At these events, it was important for at least one partner to “work the crowd” and direct women to the booth, while another partner stayed at the table to talk specifically about the study. Our displays included tchotchkes such as rings with colored lights/buttons with our study logo. Not only did these tchotchkes bring potential participants to our table to investigate, once participants were given the ring or button to wear, but they also became moving “billboards” for the study and could promote it throughout the venue for several days, thus bringing attention to the study.

Our study team members who were also NWP/WP community partners are strong proponents of direct, face-to-face recruitment opportunities from the start of the study. This was further supported by the responses, and lack thereof, from the NWP site coordinators whom we did not initially engage face-to-face, but rather through conference calls. Therefore, several NWP teams were invited to gather for a “user” meeting while attending another national conference to meet the academic partner (HO-B) in person and learn more about the study. All study team members addressed the group and had candid discussions. From this meeting, five NWP site coordinators agreed to arrange for eligible survivors in their area to attend “spit parties,” which are in-person group meetings of potential participants who could complete the study requirements (i.e., consents, surveys, and saliva sample) with the support of study team members.

The Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation’s Army of Women (AOW) offers a website registration process for women to register online to receive information about opportunities for participation in research studies. Once a woman registers, she receives periodic emails (e-blasts) with information about ongoing studies and opportunities to participate. AOW staff worked with us to develop the e-blast messages detailing brief study background and eligibility criteria.

One NWP volunteer discussed the study at a breast cancer support group in New York City and provided contact information for women to call the study staff to determine eligibility.

Results

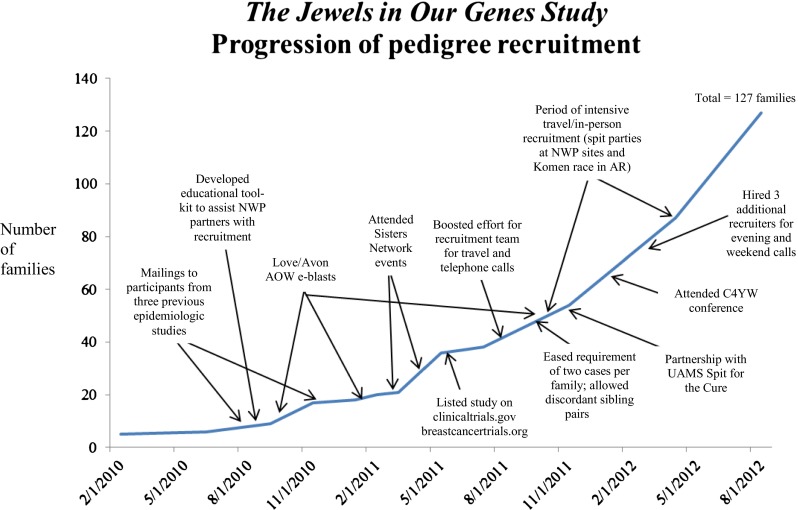

The study had a specified recruitment timeline that extended 9 months beyond the planned period in order to allow us to reach our recruitment goals. In a true CBPR approach, the research partners brainstormed and produced new ideas to augment the initial recruitment plan. The methods were thus iterative through various venues over the time between 2010 and 2012 (Fig. 1). By fall 2012, a total of 743 African American women were contacted in total by our study staff from all recruitment sources, yielding 341 African American women (247 affected and 94 unaffected relatives) from 127 families who ultimately participated in the study.

Fig. 1.

The Jewels in Our Genes study recruitment activity timeline

Table 1 shows that our collaboration with the NWP allowed us to screen 122 women, 80 % of whom were eligible and completed the study. Approximately 29 % of our total sample was recruited directly through the NWP. We experienced a minimal response from the NWP site coordinators following the initial conference call and e-mailed materials alone. As we re-evaluated our approach, we developed a protocol that involved sending team members to NWP sites for in-person recruitment meetings in attempts to more fully engage with them to both help educate about the research study. Six sites extended invitations to the study team members to visit their programs in person to help recruit participants; these visits were easily scheduled and carried out due to the existing relationship of our team members with the NWP. Three members of our study team (DOE, DJ, MJW) have been part of the NWP for years; thus, we did not have to start at ground zero with establishing a partnership.

Table 1.

Recruitment yield according to method and source

| The National Witness Projecta | Recruitment at National Conferences/Eventsb | Love/Avon Army of Women | Participated in previous research | Support group | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential participants contacted | 122 | 122 | 272 | 218 | 9 | 743 |

| Not eligible | 3 | 17 | 65 | 81 | 1 | 167 |

| Unable to contact/refused | 21 | 66 | 91 | 57 | 0 | 235 |

| Completed the study | 98 | 39 | 116 | 80 | 8 | 341 |

| Percentage of all contacted who participated | 80.3 % | 32.0 % | 42.6 % | 36.7 % | 88.9 % | 45.9 % |

| Percentage of all eligible who participated | 82.4 % | 37.1 % | 56.0 % | 58.4 % | 100 % | 59.2 % |

aIncludes recruitment by partnering PIs/sites and from in-person site visits

bFace-to-face and national meetings other than the National Witness Project, but were staffed by National Witness Project members

Recruitment at national conferences and events provided us with 122 potentially eligible women; 37 % of eligible women completed the study. A total of 272 women responded to our AOW e-blasts; we were able to successfully recruit 43 %.

Of the 218 women whose names we received from previous studies, 80 completed the study (37 % yield). Here, 58 % of eligible women participated. Many women were ineligible because they lacked a living family member who had breast cancer and an older unaffected sister. Fifty-eight percent of women who participated in previous studies and are eligible participated in our study. Interestingly, this yield is similar to that for the Love/Avon AOW rate of 56 %. However, these two methods differ markedly in their cost and time; the original study staff had to obtain necessary IRB amendments for additional mailings.

Table 2 shows variation in several characteristics according to recruitment method/source. Our results highlight differences in education, where women enrolled in the Army of Women were more likely to have some college or be a college graduate compared to the other methods, less likely to be a current smoker, later age that menstrual periods stopped permanently, more likely to have a mother alive (in spite of similar age distributions across types), and overall have smaller families than all other recruitment methods.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Jewels in Our Genes study

| Characteristics Mean (SD) or N (%) | Recruitment method/source | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Love/Avon Army of Women (N = 116) | Participated in previous research (N = 80) | Recruitment at National Conferences/Events (N = 39) | The National Witness Project + Support group (N = 106) | p value | |

| Ever diagnosed with breast cancer (yes) | 86 (74.1 %) | 55 (68.8 %) | 31 (79.5 %) | 75 (70.8 %) | 0.61 |

| Age at diagnosis for cases, age at study entry for controls, years (N = 234) | 50.5 (12.6) | 51.0 (11.7) | 49.2 (12.4) | 50.7 (11.6) | 0.93 |

| Current BMI (kg/m2) | 28.9 (6.6) | 31.5 (6.3) | 31.4 (7.3) | 31.8 (7.3) | 0.01 |

| Highest level of education completed (N = 337) | |||||

| ≤High school/GED | 12 (10.4 %) | 22 (28.2 %) | 6(15.4 %) | 24 (22.9 %) | 0.01 |

| Some college | 28 (24.4 %) | 26 (33.3 %) | 15(38.5 %) | 38 (36.2 %) | |

| College graduate or more | 75 (65.2 %) | 30 (38.5 %) | 18(46.2 %) | 43 (41.0 %) | |

| Smoked at least 100 cigarettes (Yes) | 39 (33.6 %) | 44 (55.0 %) | 10 (25.6 %) | 37 (34.9 %) | 0.01 |

| Current smoker (N = 340) | |||||

| Yes | 10 (8.6 %) | 10 (12.7 %) | 0 ( %) | 13 (12.3 %) | 0.01 |

| No | 29 (25.0 %) | 33 (41.8 %) | 10 (25.6 %) | 24 (22.6 %) | |

| Never smoked | 77 (66.4 %) | 36 (45.6 %) | 29 (74.6 %) | 69 (65.1 %) | |

| Age at menarche (N = 334) | 12.4 (1.68) | 12.3 (1.9) | 12.1(1.9) | 12.9 (1.9) | 0.08 |

| Number of pregnancies (N = 339) | 3.0 (2.2) | 3.4 (2.2) | 2.7 (1.9) | 2.8 (1.8) | 0.25 |

| Age at first full-term stillbirth (N = 265) | 23.27 (5.3) | 21.5 (5.3) | 22.3 (5.8) | 21.8 (5.8) | 0.23 |

| Number of full-term births (N = 305) | 1.93 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.5) | 2.4 (1.7) | 0.10 |

| Ever breastfeed (N = 339) | |||||

| Yes | 49 (42.2 %) | 28 (35.0 %) | 11 (29.0 %) | 29 (27.6 %) | 0.11 |

| No | 39 (33.6 %) | 38 (47.5 %) | 19 (50.0 %) | 56 (53.3 %) | |

| NA | 28 (24.1 %) | 14 (17.5 %) | 8 (21.1 %) | 20 (19.1 %) | |

| Age menstrual periods stop permanently (N = 282) | 46.5 (7.7) | 45.3 (7.8) | 40.2 (7.6) | 42.9 (7.7) | 0.01 |

| Age at first mammogram (N = 326) | 36.5 (9.1) | 39.2 (10.8) | 36.0 (8.7) | 38.3 (9.7) | 0.18 |

| Mother alive | 61 (52.6 %) | 31 (38.8 %) | 15 (38.5 %) | 29 (27.4 %) | 0.01 |

| Number of sisters | 2.3 (1.9) | 2.4 (2.2) | 2.7 (1.8) | 3.4 (2.7) | 0.01 |

| Number of brothers | 1.7 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.9) | 2.4 (2.2) | 2.6 (2.4) | 0.01 |

| Number of daughters | 0.9 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.2) | 0.40 |

| Number of sons | 0.8 (0.9) | 1.0 (1.01) | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.1) | 0.28 |

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate the effectiveness and necessity of a CBPR orientation for a successful academic-community partnership for recruitment of African American families for research, confirming outcomes by Sadler et al. (2005). Our findings point to differences in samples based on recruitment source; we believe that using multiple and varied recruitment methods allows for more representative sample. Although successful, it is challenging to identify a “best method” for recruitment as all approaches “worked” and it required all methods to achieve the recruitment goals. Future research should determine the best approach for specific studies and their associated costs including the labor intensiveness we identified. Our results offer significant keys to minority recruitment that can be applied to future studies.

Face-to-face activities often yielded more immediate results than other methods, as some participants were more likely to participate on site with their relatives with the chance to interact with study staff in person. This experience is further supported by previous research that showed positive outcomes for face-to-face contact methods for African Americans for genetics research (Satia et al. 2005). In addition, our face-to-face activities with the community group were successful as they included education about different types of research, the risks and benefits of research, and the process of research.

E-mail/e-blasts through the AOW produced more total numbers of women (n = 272), but with more ineligibles or unable to contact (57 %). AOW accrual was considered very cost effective at $12.93/woman accrued and $5.51/woman responding ($1,500/116 and $1,500/272, respectively) (not including the costs of follow-up phone calls).

Our partnership with previous investigators was a very fruitful approach, confirming previous outcomes (Sadler et al. 2005) which demonstrated that participants who are receptive to one study are more likely to participate in another. In addition, knowledge of family history of breast cancer allowed for targeted recruitment. Even though the women responded as being interested in our study, we still experienced difficulties making contact. Obtaining permission to contact previous study participants through letters produced a relatively high yield per contact (80/218 woman in pool) with respect to the staff effort and time expended. Sending letters to participants from prior studies did not require staff travel but did require effort on the part of the original study team. Other researchers who became our partners were willing to sign on after receiving letters and/or having conversations about the study and its overall goals with the principal investigator.

Using multiple methods had the advantage of potentially enhancing the representativeness of the sample. The NWP sampling process represented a broad socioeconomic and geographic spectrum of African American women across multiple states in the Eastern, Southern, Midwestern, and Western USA, from very low income to higher income. Women recruited through the Army of Women had routine access to computers and the internet and therefore included younger women and those who are more likely to have been from at least middle income and higher socioeconomic and educational levels. This may be true of women who had participated in previous research as well.

All participants, regardless of recruitment method, required multiple follow-up phone calls for the following purposes: (1) to confirm that the participant was indeed interested and ready to participate, (2) to confirm that the woman was eligible, (3) to confirm that the woman had appropriate family members who also agreed to participate, (4) to check/correct completion of study materials and specimens, and (5) to set up conference calls or three-way calls with women who wanted to participate but were unable to adequately convey the study parameters to their relative(s) and wanted assistance in this process. For each woman who participated in the study, a range of three to eight telephone calls were made to obtain all approvals, materials, and samples. These telephone calls often had to be made in the evenings/weekends to reach women instead of answering machines. Telephone calls were initially made through the study coordinator from the academic setting. The NWP study team suggested that it would be more effective for them to make the calls as they were (a) more recognizable to the participants (from meeting and recruiting many of them at face-to-face events) and (b) race concordant. This resulted in improved call success and study accrual. As the pool of potential candidates grew in the last months of the study, we trained and paid a team of Buffalo WP members to help make calls to complete accruals.

An important administrative lesson for future recruitment of families for genetic studies, especially in minority populations, is the need to budget appropriately for (1) the high level of contact needed on the part of the recruiters, (2) culturally/racially concordant telephone follow-up support, (3) face-to-face meetings with prospective study participants where possible, and (4) development of partnerships with existing community organizations. Further, as we have shown, although labor and cost intensive, we were successful in meeting our recruitment goals. Our approach primarily involved establishing a community partnership with our target community, educating study advocates, and the use of other supplemental, culturally targeted approaches. There are benefits and risks of any recruitment method that should be weighed carefully depending on the needs of a particular study.

Regarding face-to-face recruitment, if participants are from a national population pool, funds are required for travel and for many types of tchotchkes, gifts, incentives, and promotional materials to help generate interest and attention. Although these “give-aways” are often seen by academic partners as extraneous to the science and not necessarily productive for the objective, they contributed significant value to recruitment efforts. Our experience demonstrated that at meeting venues, a clever, eye-catching item like the large, colorful flashing rings and buttons stood out, prompted immediate attention and questions, and was a creative method for bringing considerable attention to our staff and the study. Moreover, as these rings uniquely identified the “Jewels” study, women found this particular promotional gift to be a stylish and enjoyable way to announce their own participation in the study.

In our experience, the travel by committed and knowledgeable WP study partners to meet personally with WP site coordinators and potential candidates and their relatives was crucial in establishing credibility for the study. Moreover, these face-to-face meetings provided the facts, rationale, importance, and personal appeal often missing from passive recruitment approaches. Sending the NWP team members as study representatives was the equivalent of sending an experienced, effective sales team to close a deal rather than just publishing a printed advertisement in a newspaper, especially once they had become more comfortable with the study goals. Furthermore, they were seen as credible, trusted members of the target population since they have been part of the NWP for over 15 years. Once potential participants met the WP team members and developed a personal relationship, they were more likely to respond to follow-up calls, help them reach their non-responsive family members, and complete their study materials.

While community-based recruitment results in variable recruitment rates in studies overall, race-concordance of the recruitment team with participants appears to be a significant factor (Johnson et al. 2011). Our recruitment experience is in full agreement with the systematic review by Johnson et al. (2011). We believe that initial face-to-face contact with potential study participants, ancestry-concordance of recruitment staff, and the opportunity for less invasive collection of DNA (saliva sample versus blood draw) are crucial for successful African American recruitment to research. There was a large amount of telephone follow-up required throughout the entire study process. As in other studies of African Americans (Johnson et al. 2011), participants in our study seldom responded to mailed correspondence, and even those who were enthusiastic about participating and who participated in prior epidemiologic studies needed to be contacted, reminded, or assisted multiple times to complete the process. Studies at our institutions, based on white, middle class women were not nearly as time/labor intensive. However, a local survey study of 75 white and 50 African American cancer patients showed much lower response rates (38 %) to mailed letters by African American patients compared to white patients (81 %). Conversely, 62 % of these African American patients were recruited by telephone versus only 19 % of white participants (unpublished data). Often, the African American women in our study had significant challenges that were of much higher priority (e.g., health crises of themselves or family members, and work, home, and/or financial stressors) than participating in the study. It was important that the study members making the telephone calls to participants understood, valued, and were empathic to these issues.

Likewise, our team, especially our NWP team, in combination with many other studies (Bates et al. 2005; Bussey-Jones et al. 2010; Corbie-Smith 1999; Furr 2002; Tambor et al. 2002), continue to re-state the need for investigators’ awareness regarding the challenge of overcoming the hesitation or refusal to participate in research and mistrust by African Americans and other minority groups. Reluctance to respond therefore makes the process of African American recruitment inherently different from the recruitment of White/European Americans. The hesitation or refusal is based on a myriad of reasons not limited to the tragic history of the Tuskegee experiments (Corbie-Smith 1999) and impact of other research such as the more recent Henrietta Lacks example (Skloot 2010). Minority research participation in the USA is indirectly or directly impacted by the sociopolitical legacy of slavery, Jim Crow policies, and lingering perceptions and reality of racism and discrimination (Bussey-Jones et al. 2010; Johnson et al. 2011; Satia et al. 2005). Part of the solution rests on the abilities of investigators and participants from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds to understand and perceive the world through each other’s worldviews and adapt recruitment strategies to reflect knowledge learned.

By the end of the extended recruitment period, we benefitted from the multilevel, multisource process, and our recruitment yield grew exponentially once we employed various adaptive strategies. Our recruitment experiences speak to the fact that minority recruitment “takes a village,” the “village” must include members of the audience to be recruited through all stages of research—true CBPR—and the “village” must employ multiple approaches to be successful. Each recruitment activity, and even monetary incentives, might locate and get interest in participation by women, but actual consent/accrual, completion of biospecimen sample, and questionnaire required intensive, time-sensitive personal contact through telephone calls or actual meetings.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Ochs-Balcom and Erwin and Ms. Johnson are supported by a grant from Susan G. Komen for the Cure, KG090937 and NIH/NCI/CRCHD U54CA153598. We wish to thank the NWP for helping us with this work, the Buffalo WP, Rosa Bordonaro, Mary Crawford, Anne Weaver, and the rest of the Jewels team for their tireless efforts. Others who were instrumental in study recruitment include Greg Ciupak and Dr. Christine Ambrosone (Women’s Circle of Health Study), Dr. Susan Kadlubar (Spit for the Cure study), Drs. Cheryl Thompson and Li Li (Breast Density Study), Jennie Ellison (GATE/TACT study), and Teri Deans-McFarlane. Thank you to the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation’s Army of Women Program. We also wish to thank all of the families who participated in our study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

All human subjects research was approved by the University at Buffalo Health Sciences Institutional Review Board and is in full compliance with the current laws that protect human subjects in the USA.

References

- Ambrosone CB, Ciupak GL, Bandera EV, Jandorf L, Bovbjerg DH, Zirpoli G, Pawlish K, Godbold J, Furberg H, Fatone A, Valdimarsdottir H, Yao S, Li Y, Hwang H, Davis W, Roberts M, Sucheston L, Demissie K, Amend KL, Tartter P, Reilly J, Pace BW, Rohan T, Sparano J, Raptis G, Castaldi M, Estabrook A, Feldman S, Weltz C, Kemeny M. Conducting molecular epidemiological research in the age of HIPAA: a multi-institutional case-control study of breast cancer in African-American and European-American Women. J Oncol. 2009;2009:871250. doi: 10.1155/2009/871250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates BR, Lynch JA, Bevan JL, Condit CM. Warranted concerns, warranted outlooks: a focus group study of public understandings of genetic research. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(2):331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey-Jones J, Garrett J, Henderson G, Moloney M, Blumenthal C, Corbie-Smith G. The role of race and trust in tissue/blood donation for genetic research. Genet Med. 2010;12(2):116–121. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181cd6689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G. The continuing legacy of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study: considerations for clinical investigation. Am J Med Sci. 1999;317(1):5–8. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant RW, Davis RB, St George DM, Williams IC, Blumenthal C, Corbie-Smith GM. Participation in research studies: factors associated with failing to meet minority recruitment goals. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(8):634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Turturro CL. Development of an African-American role model intervention to increase breast self-examination and mammography. J Cancer Educ. 1992;7(4):311–319. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr LA. Perceptions of genetics research as harmful to society: differences among samples of African-Americans and European-Americans. Genet Test. 2002;6(1):25–30. doi: 10.1089/109065702760093889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, Peterson SK, Ramirez A, Gallion KJ, McDonald PG, Skinner CS, Bowen D. Minority recruitment in hereditary breast cancer research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(7):1146–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd TC, Muti P, Erwin DO, Womack S. An evaluation of the integration of non-traditional learning tools into a community based breast and cervical cancer education program: the Witness Project of Buffalo. BMC Cancer. 2003;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, Salvatore A, Minkler M, Lopez J, Butz A, Mosley A, Coates L, Lambert G, Potito PA, Brenner B, Rivera M, Romero H, Thompson B, Coronado G, Halstead S. Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children's Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(10):1463–1471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VA, Powell-Young YM, Torres ER, Spruill IJ. A systematic review of strategies that increase the recruitment and retention of African American adults in genetic and genomic studies. ABNF J. 2011;22(4):84–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Improving health through community organizing and community building. In: Minkler M, editor. Community organizing and community building for health and welfare. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 2012. pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E, Thompson A. An exploration of attitudes among black Americans towards psychiatric genetic research. Psychiatry. 2009;72(2):177–194. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2009.72.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs-Balcom HM, Rodriguez EM, Erwin DO. Establishing a community partnership to optimize recruitment of African American pedigrees for a genetic epidemiology study. J Community Genet. 2011;2(4):223–231. doi: 10.1007/s12687-011-0059-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler GR, Peterson M, Wasserman L, Mills P, Malcarne VL, Rock C, Ancoli-Israel S, Moore A, Weldon RN, Garcia T, Kolodner RD. Recruiting research participants at community education sites. J Cancer Educ. 2005;20(4):235–239. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2004_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satia JA, Galanko JA, Rimer BK. Methods and strategies to recruit African Americans into cancer prevention surveillance studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(3):718–721. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skloot R. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Crown Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tambor ES, Bernhardt BA, Rodgers J, Holtzman NA, Geller G. Mapping the human genome: an assessment of media coverage and public reaction. Genet Med. 2002;4(1):31–36. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CL, Li L. Association of sleep duration and breast cancer OncotypeDX recurrence score. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(3):1291–1295. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson HS, Sussner K, Schwartz MD, Edwards T, Forman A, Jandorf L, Brown K, Bovbjerg DH, Valdimarsdottir HB. Receipt of genetic counseling recommendations among black women at high risk for BRCA mutations. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16(11):1257–1262. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2012.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]