Abstract

Context:

Insulin resistance is a hallmark of metabolic syndrome (MS). It has been proposed that both polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are correlated with Insulin resistance. Therefore, PCOS and NAFLD can be attributed with insulin resistance and therefore MS. The aim of this meta-analysis was to determine whether PCOS patients are at a high risk of NAFLD.

Evidence Acquisition:

Google scholar, Scopus, ISI Web of Science, Embase, MEDLINE, and some Iranian databases such as scientific information database (SID), IranMedex, and MagIran were searched to identify relevant studies. We included all papers regardless of their language from January 1985 to June 2013. By using data on prevalence of NAFLD in patients with and without PCOS, odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated in each study. Chi-squared test was used to assess heterogeneity between studies.

Results:

We finally included seven eligible studies. According to chi-squared test, there was a significant heterogeneity (73.6%) between studies (P = 0.001). NAFLD prevalence was significantly higher in patients with PCOS compared to healthy control, with an overall OR of 3.93 (95% CI: 2.17, 7.11).There was no significant publication bias based on Begg's and Egger's tests.

Conclusions:

According to the results of this meta-analysis, there was a high risk of NAFLD in women with PCOS. We suggest evaluating patients with PCOS regarding NAFLD.

Keywords: Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Insulin Resistance, Metabolic Syndrome, Meta-Analysis

1. Context

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), as one of the most common reasons of chronic liver disease in western countries, is characterized by accumulation of fat in hepatocytes without presence of significant consumption of alcohol (1, 2). This disorder includes a simple steatosis, which can progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Patients with NASH can also develop liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (2). A powerful correlation between NAFLD and insulin resistance has been proposed. This correlation may play a prominent role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD (1, 3). By considering insulin resistance as a hallmark of metabolic syndrome (MS), NAFLD can be considered as hepatic component of MS (4-7). Another disease with a powerful association with MS is polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) (1). PCOS as the most common endocrine disorder among women at child bearing age (affecting up to 10%) is characterized by hyperandrogenism and ovulatory dysfunction. hirsutism, acne, and androgenic type of alopecia are common clinical presentations of hyperandrogenism and ovulary dysfunction can be expressed with oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea (2, 8). Although, a higher frequency of dyslipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance test and diabetes mellitus (DM) has been reported in these patients, indicating the association of this disease with MS (2). Approximately 50% of patients with PCOS have insulin resistance and therefore can be considered as patients with MS (1). It is concluded that PCOS and NAFLD can be coincident via insulin resistance and therefore MS (9). On the other hand, some original studies showed that NAFLD is common in patients with PCOS (4, 8-10). Screening patients with PCOS for NAFLD is an issue of debate. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to provide a clear and exact answer for this question that whether patients with PCOS are at a higher risk of NAFLD.

2. Evidence Acquisition

2.1. Search Strategy

An electronic literature search was performed using key terms of "PCOS", "NAFLD" and "insulin resistance", and all their synonyms in Google scholar, Scopus, ISI Web of Science, Embase, MEDLINE and some Iranian databases such as scientific information database (SID), IranMedex and MagIran. Two investigators separately did all of searches and quality assessment procedures and any disagreements between them were resolved by the third author. We included all papers regardless of their language from January 1985 to June 2013. We also searched Cochrane library especially for clinical trials registry to ensure minimum publication bias. In addition, all of references of relevant review studies were checked to find further investigations not found before in primary electronic search.

2.2. Study Selection

Studies with all languages were included according to the following criteria:

Having a reasonable study design to assess prevalence of NAFLD in patients with PCOS, such as cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies;

Using the Rotterdam criteria to diagnose PCOS and abdominal ultrasound for fatty liver;

Studies that clearly determined the prevalence of NAFLD in patients with PCOS compared to matched controls;

Studies that had an appropriate statistical method to compare NAFLD prevalence in patients with PCOS and controls.

In addition, exclusion criteria were review, case report, letter to editor, editorial and commentarial papers; studies without age, weight/BMI matched control group; studies with very low quality assessment score; studies that only determined the prevalence of NASH in patients with PCOS and those that did not use a definitive method to diagnose PCOS.

2.3. Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

Quality assessment was performed using the STROBE Statement (11), a checklist that evaluates observational and report studies. This checklist evaluates 22 items. Each item has one score and a total score of 22. The studies were evaluated by two reviewers. The scores were optimized together, and if the scores were different more than 10%, reviewers negotiated in a similar score. After evaluating studies, Information was extracted from each study and imported to Microsoft Office Excel 2010 Software including first author's name, publication year, country, study design, diagnostic method of NAFLD and PCOS, sample size of PCOS and control groups, quality assessment score and prevalence of NAFLD in patients with and without PCOS.

2.4. Definitions

PCOS was defined as the presence of two of the three following characteristics, according to the Rotterdam criteria (12):

clinical and/or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism;

oligoovulation or anovulation; or

polycystic ovaries (PCO) at ultrasound evaluation.

We also defined NAFLD as the presence of ultrasonography findings of hepatic steatosis and fatty liver disease. For example, a significant increase in fine echoes of liver parenchyma with impaired visualization of the intrahepatic vessels and posterior beam attenuation was considered for NAFLD diagnosis with ultrasonography.

2.5. Analytical Methods

By using data regarding the prevalence of NAFLD in patients with and without PCOS, odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated in each study. Chi-squared test was used to assess heterogeneity between studies. P value ≤ 0.1 represented a significant heterogeneity. According to the result of heterogeneity test, we used random Mantel-Haenszel model (in case of heterogeneity) or fixed Mantel-Haenszel model (in case of homogeneity) to achieve pooled OR. Publication bias was checked statistically using both Egger regression and Begg-Mazumdar tests, and a P value less than 0.05 was considered as significant publication bias. We also checked the funnel plot figure visually for publication bias. All analyses were performed with STATA software version 11 for windows.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

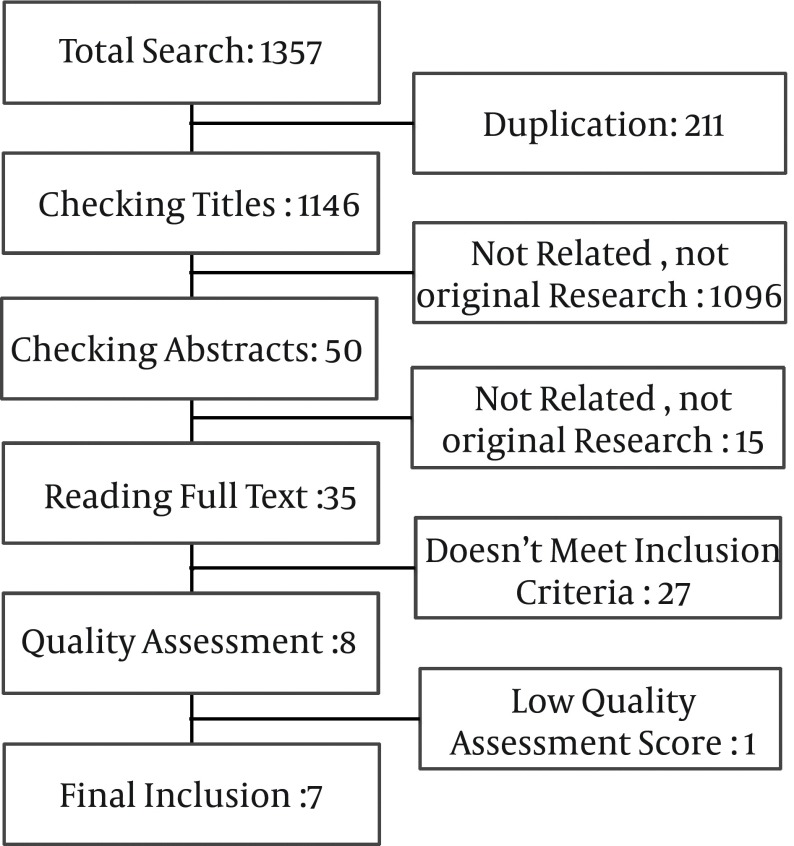

A total of 1357 manuscripts were obtained in online search in different databases. After that, 211 duplicate papers were excluded. Initial assessment with checking the title of articles led to excluding 1096 other manuscripts because of being not an original research, appropriate manuscript or related titles. Next, in abstract evaluation, 15 manuscripts were found to be not related or an original article. We read 35 full papers to check the studies for inclusion criteria. From these studies, 27 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Besides, one manuscript was excluded after quality assessment. We finally included seven well quality investigations (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Results of Search Strategy.

3.2. Characteristics of Studies

We included seven investigations from six counties, which provided data on the prevalence of NAFLD in patients with and without PCOS. Two studies from China and one from each of Athens, Chile, India, Egypt, and Brazil. In total, 42.5% of studies were from Asia, 28.5% from the America, 14.5% from Africa and 14.5% from the Europe. There were four case control studies (57.1%), two cohort studies (28.5%) and one cross-sectional study (14.2%). One study was published in 2007, one in 2008, two in 2010, two in 2012 and one in 2013. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the investigations enrolled in this meta-analysis.

Table 1. Characteristics of Studies a.

| Author | Year | Country | Method | Sample size (PCOS) | Healthy control | QAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerda, C (1) | 2007 | Chile | Cohort | 41 | 31 | 20 |

| Zheng, RH (13) | 2008 | China | Case-Control | 60 | 60 | 18 |

| Vassilatou, E (2) | 2010 | Greece | Case-Control | 57 | 60 | 19 |

| Qu, Z (22) | 2010 | China | Case-Control | 306 | 286 | 18 |

| Faisal, A (9) | 2012 | Egypt | Cohort | 53 | 32 | 19 |

| Zueff, LF (8) | 2012 | Brazil | Case-Control | 45 | 45 | 20 |

| Karoli, R (4) | 2013 | India | Cohort | 54 | 55 | 20 |

a Abbreviation: PCOS, Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome; QAS, Quality Assessment Score.

Age, BMI, LDL, HDL, and TG were available in five studies (1, 2, 4, 8, 9). ALT and AST were measured in four studies, alkaline phosphatase in only one study (9), and fasting insulin in five studies (1, 2, 4, 8, 13), with overall mean values shown in Table 2. In addition, Table 3 shows data on prevalence of NAFLD in patients with and without PCOS.

Table 2. The Overall Mean Amounts of Age, BMI, ALT, AST, LDL, HDL, TG, Fasting Insulin and Alkaline Phosphatase in Studies a,b.

| PCOS Patients | Healthy Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 27.23 ± 6.61 | 28.59 ± 6.6 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.56 ± 6.51 | 29.07 ± 5.83 |

| ALT, mg/dL | 36.23 ± 17.52 | 22.06 ± 13.02 |

| AST, mg/dL | 33.53 ± 13.97 | 23.92 ± 11.63 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 114.34 ± 30.25 | 106.39 ± 25.16 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 46.07 ± 9.63 | 49.13 ± 8.9 |

| TG, mg/dL | 123.86 ± 50.81 | 124.33 ± 41.95 |

| Fasting insulin, µIU/L | 13.47 ± 10.58 | 10.21 ± 6.59 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase, mg/dL | 87.3 ± 54.6 | 82.4 ± 64.2 |

a Abbreviation: PCOS: Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome; BMI: Body Mass Index; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferases; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; TG: Triglyceride.

b All amounts are mean ± Standard deviation.

Table 3. Prevalence of NAFLD and PCOS-NAFLD Coexist in Studies a.

| Author | PCOS | Control | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFLD+ | NAFLD- | NAFLD+ | NAFLD- | ||

| Cerda, C (1) | 17 (41.46%) | 24 (58.54%) | 6 (19.36%) | 25 (80.64%) | 2.951 (0.996-8.745) |

| Zheng, RH (13) | 25 (41.67%) | 35 (58.33%) | 12 (20%) | 48 (80%) | 2.857 (1.265-6.452) |

| Vassilatou, E (2) | 21 (36.84%) | 36 (63.16%) | 12 (20%) | 48 (80%) | 2.333 (1.017-5.354) |

| Qu, Z (22) | 94 (30.72%) | 212 (69.28%) | 50 (17.48%) | 236 (82.52%) | 2.093 (1.417-3.091) |

| Faisal, A (9) | 46 (86.79%) | 7 (13.21%) | 4 (12.5%) | 28 (87.5%) | 46.000 (12.347-171.379) |

| Zueff, LF (8) | 33 (73.33%) | 12 (26.67%) | 21 (46.67%) | 24 (53.33%) | 3.143 (1.300-7.599) |

| Karoli, R (4) | 36 (66.67%) | 18 (33.33%) | 14 (25.45%) | 41 (74.55%) | 5.857 (2.555-13.427) |

a Abbreviation: PCOS: Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome; NAFLD: Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.

3.3. Meta-Analysis of NAFLD Prevalence in PCOS Patients

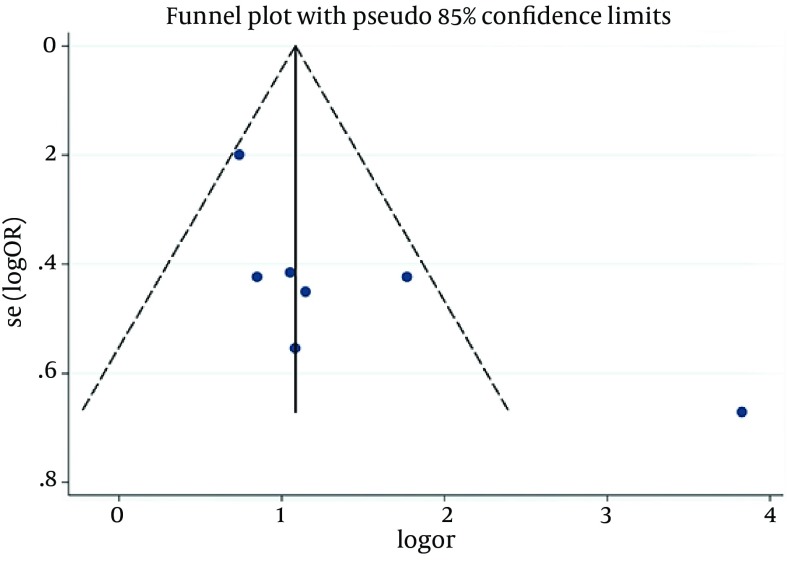

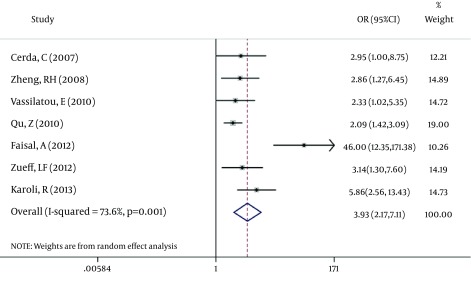

According to chi-squared test, there was a significant heterogeneity (73.6%) between studies (P = 0.001), so in a random method overall OR was 3.93 with a 95% CI of 2.17-7.11 (Figure 2). There was not a significant publication bias based on the Begg's and Egger's tests (Tables 4 and 5). In addition, Funnel plot (Figure 3) was relatively symmetric, which suggested no publication bias.

Figure 2. Correlation Between NAFLD and PCOS.

Table 4. Publication Bias Checked by the Begg's Test.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Kendall's Score (P-Q) | 11 |

| Std. Deviation of Score | 6.66 |

| P value | 0.099 |

Table 5. Publication Bias Checked by the Egger's Test.

| Std-Eff. | Std. Err. | P > |t| | 95% Conf. Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | 0.5329 | 0.983 | -1.3817 | 1.3583 |

| Bias | 1.4609 | 0.076 | -.4954 | 7.0157 |

Figure 3. Funnel Plot of Studies.

4. Discussion

NAFLD refers to a spectrum of liver damage ranging from simple steatosis to NASH, advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis (14). NAFLD is a condition of accumulation of fat, which exceeds 5% in hepatocytes. NAFLD primarily results from insulin resistance, and thus frequently occurs as a part of metabolic changes of obesity, type II diabetes, and dyslipidemia. Estimated prevalence of NAFLD in general population ranges from 3% to 24% (15), while different studies detected a higher prevalence of NAFLD in PCOS as the most common endocrinopathy affecting women of reproductive age (1, 2, 8). The aim of this meta-analysis was to determine whether patients with PCOS are at a high risk of NAFLD.

Women with PCOS are at a substantial risk of developing metabolic abnormalities such as glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia and MS (16, 17). Prevalence of MS in women with PCOS is significantly higher than age-matched counterparts from the general population. More recently, a link between PCOS and NAFLD has been demonstrated according to their some same etiology such as obesity and insulin resistance (18-21). We found that patients with PCOS had a 3.93 fold increase in the risk of coexist NAFLD (95% CI: 2.17-7.11). This increased risk of NAFLD in patients with PCOS is due to their same etiology. On the other hand, the prevalence of NAFLD in women with PCOS varies in different countries. The prevalence of NAFLD in Chinese women with PCOS was 32.9% (22), 55% in the American women, 41.5% in Chilean women (1, 23) and 73.3% in Brazilian women (8). It seems that these differences are related to genetic, ethnicity and specially lifestyle such as food habits and exercise. Several investigations proved that lifestyle modification could reduce MS prevalence and severity (24, 25).

Both PCOS and NAFLD have high prevalence in obese women. Angolo in his review stated that American ethnic group, central obesity, type II diabetes, hyperlipidemia and hypertension are risk factors of NAFLD (26). Qu et al. (22) reported that women with both PCOS and NAFLD had higher BMI compared to those without NAFLD. In addition, studies which reported a high prevalence of NAFLD in patients with PCOS stated higher BMI in their patients compared to those studies with lower prevalence of NAFLD. These observations showed that obesity is a main reason for coincident of NAFLD and PCOS. Many authors believed that NAFLD and PCOS are hepatic and ovarian manifestations of MS.

The role of insulin resistance (IR) in PCOS and NAFLD has been evaluated in many studies (27-31). The prevalence of IR in PCOS plus NAFLD patients in evaluated studies was more than PCOS patients without NAFLD. Excess dietary fat, increased delivery of free fatty acids to the liver, insufficient fatty acid oxidation, and increased de novo lip genesis may lead to accumulation of fat in the liver. IR may enhance hepatic fat accumulation by increasing free fatty acid delivery and through the effect of hyperinsulinemia to stimulate anabolic processes (27). Insulin-sensitizing medications such as metformin had useful effects on NAFLD and PCOS (32, 33). Most common biochemical indexes in NAFLD patients are increased levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and to a lesser extent aspartate aminotransferase (AST). ALT is a more sensitive biomarker than AST for impaired insulin signaling and NAFLD (34, 35). Furthermore, it had been demonstrated that NAFLD is the most common cause of persistent elevated serum ALT level in general population of Iran (36).

Our study had some inevitable limitations. Although ultrasonography (US) is usually used to diagnose NAFLD in clinic, liver biopsy is the gold standard method (37-39). Since US had been used in evaluated studies as a diagnostic method for NAFLD as a high sensitive method, it can overestimate prevalence of NAFLD. Another limitation was the small sample size in the evaluated studies, so we could not perform any subgroup analysis.

In conclusion, according to the results of this meta-analysis, there is a high chance of NAFLD in women with PCOS. We suggest evaluating patients with PCOS regarding NAFLD. In this regards, general physicians have an essential role, because patients refer to them firstly. We suggest evaluating BMI, liver function test and other risk factors such as diabetes mellitus in patients by general physicians and referring them to a gastrointestinologist in case of any risk factor.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions:Ramezani Binabaj M made an electronic literature search. A critical appraisal (CA) was performed by Karimi Sari H, Motalebi M and Ramezani Binabaj. M. Rezaee-Zavareh M and Karimi Sari H analyzed the data. All authors contributed in interpretation of results. Alavian SM read the manuscript and supervised the team.

References

- 1.Cerda C, Perez-Ayuso RM, Riquelme A, Soza A, Villaseca P, Sir-Petermann T, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Hepatol. 2007;47(3):412–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vassilatou E, Lafoyianni S, Vryonidou A, Ioannidis D, Kosma L, Katsoulis K, et al. Increased androgen bioavailability is associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(1):212–20. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saki F, Karamizadeh Z. Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and Fatty liver in obese Iranian children. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(5) doi: 10.5812/ircmj.6656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karoli R, Fatima J, Chandra A, Gupta U, Islam FU, Singh G. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2013;6(1):9–14. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.112370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranova A, Tran TP, Birerdinc A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: association of polycystic ovary syndrome with metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(7):801–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Morselli-Labate AM, Bianchi G, Bugianesi E, McCullough AJ, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. Am J Med. 1999;107(5):450–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahsaee S, Ghazizade A, Yazdanpanah M, Enhesari A, Malekzadeh R. Assessment of NAFLD cases and its correlation to BMI and metabolic syndrome in healthy blood donors in Kerman. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2012;5(4):183–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zueff LF, Martins WP, Vieira CS, Ferriani RA. Ultrasonographic and laboratory markers of metabolic and cardiovascular disease risk in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39(3):341–7. doi: 10.1002/uog.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FAISAL A, GADALLAH AN, ZYITON A, ESKANDER A. Liver Affection in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). ScholarlyEditions; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G, Tomassetti S, Bugianesi E, Lenzi M, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a feature of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1844–50. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmina E, Azziz R. Diagnosis, phenotype, and prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2006;86 Suppl 1:S7–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng RH, Ding CF. [Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2008;43(2):98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bugianesi E, Moscatiello S, Ciaravella MF, Marchesini G. Insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(17):1941–51. doi: 10.2174/138161210791208875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark JM. The epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40 Suppl 1:S5–10. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000168638.84840.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, Norman RJ. Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4):347–63. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cussons AJ, Stuckey BG, Watts GF. Cardiovascular disease in the polycystic ovary syndrome: new insights and perspectives. Atherosclerosis. 2006;185(2):227–39. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preiss D, Sattar N, Harborne L, Norman J, Fleming R. The effects of 8 months of metformin on circulating GGT and ALT levels in obese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(9):1337–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brzozowska MM, Ostapowicz G, Weltman MD. An association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(2):243–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Targher G, Solagna E, Tosi F, Castello R, Spiazzi G, Zoppini G, et al. Abnormal serum alanine aminotransferase levels are associated with impaired insulin sensitivity in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2009;32(8):695–700. doi: 10.3275/6375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutierrez-Grobe Y, Ponciano-Rodriguez G, Ramos MH, Uribe M, Mendez-Sanchez N. Prevalence of non alcoholic fatty liver disease in premenopausal, posmenopausal and polycystic ovary syndrome women. The role of estrogens. Ann Hepatol. 2010;9(4):402–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qu Z, Zhu Y, Jiang J, Shi Y, Chen Z. The clinical characteristics and etiological study of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese women with PCOS. Iran J Reprod Med. 2013;11(9):725–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gambarin-Gelwan M, Kinkhabwala SV, Schiano TD, Bodian C, Yeh HC, Futterweit W. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(4):496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Chrysohoou C, Skoumas J, Tousoulis D, Toutouza M, et al. Impact of lifestyle habits on the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among Greek adults from the ATTICA study. Am Heart J. 2004;147(1):106–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(03)00442-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orchard TJ, Temprosa M, Goldberg R, Haffner S, Ratner R, Marcovina S, et al. The effect of metformin and intensive lifestyle intervention on the metabolic syndrome: the Diabetes Prevention Program randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(8):611–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angulo P. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr Rev. 2007;65(6 Pt 2):S57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Utzschneider KM, Kahn SE. Review: The role of insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(12):4753–61. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bugianesi E, Gastaldelli A, Vanni E, Gambino R, Cassader M, Baldi S, et al. Insulin resistance in non-diabetic patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: sites and mechanisms. Diabetologia. 2005;48(4):634–42. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angulo P, Alba LM, Petrovic LM, Adams LA, Lindor KD, Jensen MD. Leptin, insulin resistance, and liver fibrosis in human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2004;41(6):943–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Insulin resistance in PCOS. Endocrine. 2006;30(1):13–7. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:30:1:13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Christakou CD. Insulin Resistance in PCOS. Springer; 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozturk ZA, Kadayifci A. Insulin sensitizers for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2014;6(4):199–206. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i4.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Awartani KA, Cheung AP. Metformin and polycystic ovary syndrome: a literature review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2002;24(5):393–401. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goessling W, Massaro JM, Vasan RS, Fox CS. Aminotransferase levels and 20-year risk of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Gastroenterol J. 2008;135(6):1935–44. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang Y, Ryu S, Sung E, Jang Y. Higher concentrations of alanine aminotransferase within the reference interval predict nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Chem. 2007;53(4):686–92. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.081257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jamali R, Khonsari M, Merat S, Khoshnia M, Jafari E, Bahram Kalhori A, et al. Persistent alanine aminotransferase elevation among the general Iranian population: prevalence and causes. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(18):2867–71. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saadeh S, Younossi ZM, Remer EM, Gramlich T, Ong JP, Hurley M, et al. The utility of radiological imaging in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(3):745–50. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegelman ES, Rosen MA. Imaging of hepatic steatosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21(1):71–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamali R. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Walter Siegenthaler; 2013. [Google Scholar]