Abstract

Background:

Nucleoside analogues are recommended as antiviral treatments for patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV)-associated liver failure. Clinical data comparing entecavir (ETV) and lamivudine (LAM) are inconsistent in this setting.

Objectives:

To compare the efficacy and safety of ETV and LAM in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB)-associated liver failure.

Patients and Methods:

A literature search was performed on articles published until January 2014 on therapy with ETV and LAM for patients with CHB-associated liver failure. Risk ratio (RR) and mean difference (MD) were used to measure the effects. Survival rate was the primary efficacy measure, while total bilirubin (TBIL), prothrombin activity (PTA) changes and HBV DNA negative change rates were secondary efficacy measures. A quantitative meta-analysis was performed to compare the efficacy of the two drugs. Safety of ETV and LAM was observed.

Results:

Four randomized controlled trials and nine retrospective cohort studies comprising a total of 1549 patients were selected. Overall analysis revealed comparable survival rates between patients received ETV and those received LAM (4 weeks: RR = 1.03, 95%CI [0.89, 1.18], P = 0.73; 8 weeks: RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.85, 1.14], P = 0.84; 12 weeks: RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.90, 1.08], P = 0.70; 24 weeks: RR = 1.02, 95% CI [0.94, 1.10], P = 0.66). After 24 weeks of treatment, patients treated with ETV had a significantly lower TBIL levels (MD = -37.34, 95% CI [-63.57, -11.11], P = 0.005), higher PTA levels (MD = 11.10, 95% CI [2.47, 19.73], P = 0.01) and higher HBV DNA negative rates (RR = 2.76, 95% CI [1.69, 4.51], P < 0.0001) than those treated with LAM. In addition, no drug related adverse effects were observed in the two treatment groups.

Conclusions:

ETV and LAM treatments had similar effects to improve 24 weeks survival rate of patients with CHB-associated liver failure, but ETV was associated with greater clinical improvement. Both drugs were tolerated well during the treatment. It is suggested to perform further studies to verify the results.

Keywords: Entecavir, Lamivudine, LAM, Hepatitis B, Liver Failure

1. Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. China has one of the world’s highest rates of HBV infection despite availability of an effective vaccine (1). It is estimated that 93 million individuals in China are infected with HBV, including 20 million with active chronic hepatitis B (CHB) (2). Patients with chronic HBV infection are at an increased risk of developing liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (3). In some cases, patients may develop severe acute exacerbations, resulting in liver failure and death. Liver failure is inability of the liver to perform its normal synthetic, metabolic, excretory and biotransformation functions, and it is usually manifested as coagulopathy, jaundice, ascites and hepatic encephalopathy (4). In China, HBV infection is the leading cause of liver failure, which can develop to acute liver failure (ALF), subacute liver failure (SALF), acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) or chronic liver failure (CLF) (5). HBV-induced liver failure is usually severe and associated with a high mortality rate (5). In the “Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Liver Failure” (6), “Acute on Chronic Liver Failure: Consensus Recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver” (7) and “AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011” (8) reports, nucleoside analogue (NA) drugs were recommended as antivirus treatment for patients with HBV-associated liver failure. Both entecavir (ETV) and lamivudine (LAM) are NAs with a high antiviral activity. ETV is the strongest commercially available NA and the first line drug for HBV treatment in China market. ETV is also clearly superior to LAM as a therapy for CHB (9), and ETV appears to be better than LAM for patients with HBV-associated liver failure, at least theoretically. Nevertheless, clinical data are inconsistent regarding the efficacy of ETV and LAM in this clinical setting (10-12). Studies performed by Huo (10) and Lei (11) indicated that the efficacy of ETV was better than LAM, while Jing Lai’s study (12) showed that short-term efficacy of ETV versus LAM was similar for patients with ACLF. ETV was reported to be potentially related to fatal lactic acidosis in severely decompensated patients with cirrhosis (13). Furthermore, investigators from Hong-Kong reported a mortality rate of 19% in ETV treated patients with acute exacerbation of CHB compared to only 4% in LAM treated controls (14). In this study, 36 and 117 patients were treated with ETV and LAM, respectively. By week 48, seven patients in the ETV group and five patients in the LAM group died. They concluded that ETV treatment was associated with increased mortality in patients with severe acute exacerbation of CHB. The reason for increased short-term mortality in ETV-treated patients was not completely understood. Although many studies were conducted to evaluate the effects of ETV or LAM in the treatment of patients with CHB-associated liver failure, few systematic reviews compared the efficacy of the two drugs. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis of prospective and retrospective studies to explore the efficacy and safety of ETV compared to LAM in patients with CHB-associated liver failure.

2. Objectives

We aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of ETV and LAM in the treatment of patients with CHB-associated liver failure.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included any randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational cohort studies that provided data to calculate survival rate related to ETV and LAM therapy for patients with CHB-associated liver failure. According to the following reports: “Prevention and Treatment Scheme for Virus Related Hepatitis ” released in 2000 (15), “Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Liver Failure” released in 2006 (6) and “Acute on Chronic Liver Failure: Consensus Recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver” released in 2009 (7), we made the criteria for choosing eligible studies in our meta-analysis.

Studies with patients meeting the following criteria were included:

Previously diagnosed CHB or HBV-associated cirrhosis;

Rapidly deepening jaundice, with total bilirubin (TBIL) five times greater than the upper limit of normality (> 85 µmol/L or > 5 mg/dL) or a daily increase ≥ 17.1 µmol/L;

Hemorrhagic tendency with international normalized ratio (INR)≥ 1.5, or prothrombin activity (PTA)≤ 40%;

HBV DNA > 103 copies/mL;

Interventional measure: LAM (100 mg/d) combined with routine comprehensive treatment in one group (LAM group); ETV (0.5 mg/d) combined with routine comprehensive treatment in another group (ETV group); and

Neutrality and comparability of the two groups for age, gender, and other biological or chemical predictors.

Exclusion criteria were:

Superinfection with hepatitis A, C, D and E virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus and others;

Other causes of chronic liver failure, such as drug-induced liver injury, auto-immune liver disease, alcoholic liver disease and inherited metabolic disease;

Patients with malignant tumors and severe blood anomalies;

Patients receiving antiviral therapy at the time they were recruited or received antiviral therapy six months prior to the study;

Non-convertible or unusable data in literature; and

Literature not published as full text.

3.2. Literature Search

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of science, Cochrane Library, Chinese BioMedical Literature (CBM), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Technological Journal of Database (VIP) and Wanfang databases for eligible articles until January 2014 without language and publication limitations. We applied a free key word or mesh word searching with the following terms: severe hepatitis B, chronic severe hepatitis B, liver failure, hepatic failure, acute on chronic liver failure, acute exacerbation, severe acute exacerbation, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis B virus infection, HBV, entecavir, ETV, lamivudine, LAM, nucleoside analog* and nucleotide analog*. After finding all articles fulfilling our selection criteria, we used search engines (i.e. Google and Baidu) to search gray literature relevant to our study. In addition, a manual search of abstracts of international liver meetings, reference lists of retrieved articles and qualitative topic reviews was performed.

3.3. Indicators of Therapeutic Efficacy

Survival rate was the primary efficacy measure for this analysis. TBIL, PTA changes and HBV DNA negative change rate were secondary efficacy measures. The safety of ETV and LAM was also observed.

3.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (Xiaoguo Zhang and Yong An) independently selected the studies and extracted data and outcomes according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Cohen's kappa coefficient was used to measure the agreement between the two reviewers. In cases of disagreement between the two reviewers, a third reviewer (Shijun Chen) examined the data and discussed the choices with the two initial reviewers. Data was incorporated only when the three reviewers reached a consensus. Collected information included basic information on the studies, sample sizes, receiver characteristics and the results. Quality assessment of included studies was performed. For RCTs, methodological quality was evaluated using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other sources of bias) described in the Cochrane Reviewer’s Handbook 5.1.0. For observational cohort studies, methodological quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (16) with some modifications to match the needs of this study. This measure assessed aspects of methodology in observational studies related to study quality, including selection of cases, comparability of populations, and assessments of outcome. Studies were graded on an ordinal star scoring scale with higher scores (more stars) representing studies of higher quality.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed by reviewing manager version 5.2.9 (Rev Man 5.2.9 from Cochrane Collaboration). Among the indicators compared, risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were used to compare survival and HBV DNA negative change rates. Mean difference (MD) and 95% CI were used to compare TBIL and PTA changes. Collected data heterogeneity was measured using the Cochran’s Q (Chi-square χ2 test) and I² tests. Fixed or random effect model was used depending on the absence or presence of significant heterogeneity. In our meta-analysis, P > 0.10 in Cochran’s Q test and I2 < 25% signified no heterogeneity, and the fixed effects model was adopted when data was pooled across studies. Otherwise, the random effects model was used. For all tests, except for tests of heterogeneity, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Funnel chart and trim and fill method (17) were used to detect possible publication biases. Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate validity and reliability of primary meta-analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics and Quality of Included Studies

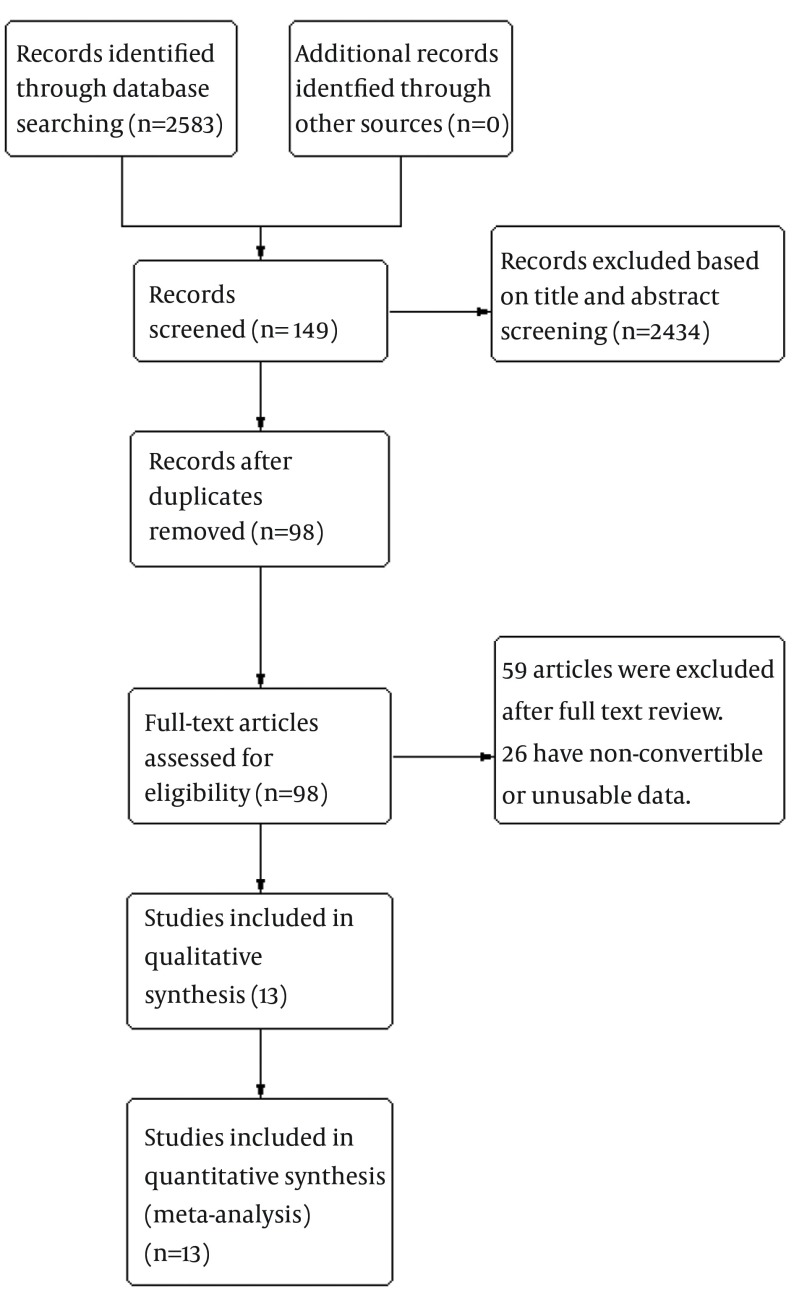

Thirteen studies comprising 1549 patients fulfilled the criteria for this meta-analysis. There was an acceptable agreement between the two reviewers for study selection (Kappa coefficient: 0.77). Of thirteen studies included, four (11, 18-20) were RCT and nine (10, 12, 21-27) were retrospective cohort studies. In total, 797 cases were included in the ETV group, and 752 cases in the LAM group. The process of selecting eligible studies in our meta-analysis is shown in Figure 1. All included studies were performed in China and reflecting the high incidence of HBV infection in China. Four articles were published in English and the rest in Chinese. Of these studies, the shortest follow-up time was 4 weeks and the longest was 24 weeks. Characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Flow-Chart Identifying Eligible Studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of Thirteen Studies Included in the Meta-Analysisa.

| Study Year | Study Design | Region | Language of Paper | Number of Patients | Male | Female | Reported Endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fang Li 2008 (21) | Retrospective cohort | China | Chinese | 143 | 112 | 31 | mortality, TBIL, ALT and HBVDNA |

| Liya Huo 2008 (10) | Retrospective cohort | China | Chinese | 44 | 33 | 11 | mortality, TBIL, ALT, PTA and HBVDNA |

| Qiheng Xu 2009 (22) | Retrospective cohort | China | Chinese | 116 | NA | NA | survival, HBVDNA and TBIL |

| Cuijun Peng 2010 (23) | Retrospective cohort | China | Chinese | 92 | 63 | 29 | mortality, TBIL, and PTA |

| Jinhua Hu 2010 (18) | RCT | China | Chinese | 218 | 155 | 63 | survival, HBVDNA and MELD score |

| Xiaomin Wang 2010 (20) | RCT | China | Chinese | 74 | 62 | 12 | mortality, HBVDNA, PTA and TBIL |

| Yaoli Cui 2010 (24) | Retrospective cohort | China | English | 67 | 6 | 61 | survival, recurrence , HBV DNA and MELD score |

| Hongbo Gao 2011 (25) | Retrospective cohort | China | Chinese | 183 | NA | NA | survival, TBIL, PTA and HBVDNA |

| Tianyan Chen 2012 (26) | Retrospective cohort | China | English | 72 | 56 | 16 | mortality , recurrence and HBVDNA |

| Zhiyong Yang 2012 (19) | RCT | China | Chinese | 40 | NA | NA | survival, HBVDNA and MELD score |

| Lei Fan 2013 (11) | RCT | China | Chinese | 120 | NA | NA | mortality, TBIL, ALT PTA and HBVDNA |

| Jing Lai 2013 (12) | Retrospective cohort | China | English | 182 | 163 | 19 | mortality, MELD score and YMDD mutations |

| Junshuai Wang 2014 (27) | Retrospective cohort | China | English | 198 | NA | NA | survival, MELD score and TPPM score |

a Abbreviations: TBIL, total bilirubin; ALT, alanine transaminase; PTA, prothrombin activity; RTC, randomized controlled trial.

The overall quality of included RCTs in this meta-analysis was suboptimal. None of four RCTs reported how the allocation sequences were generated. Three studies (11, 19, 20) did not report the methods of allocation concealment, and one study (18) took an open random allocation schedule. None of the trials referred to blinding method. Methodological quality of RCTs is shown in Table 2. Quality of included observational cohort studies was assessed, and each of the studies had at least six stars. Two studies (22, 25) did not describe the comparability of ETV and LAM groups. The study conducted by Jing Lai (12) recruited hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) negative patients with ACLF but not HBeAg positive patients, thus limiting the representative capacity of this study. Quality of retrospective studies is shown in Table 3.

Table 2. Assessment of Methodological Quality of Included RCTs.

| Studies Included | Randomization | Allocation Concealment | Blinding | Incomplete Outcome Data | Selective Reporting | Other Sources of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jinhua Hu 2010 (18) | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Xianmin Wang 2010 (20) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Zhiyong Yang 2012 (19) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Lei Fan 2013 (11) | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

Table 3. Assessment of Methodological Quality of Included Observational Cohort Studiesa.

| Studies Included | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Scores | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Fang Li 2008 (21) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 9 |

| Liya Huo 2008 (10) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 9 |

| Qiheng Xu 2009 (22) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 7 | ||

| Cuijun Peng 2010 (23) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 9 |

| Yaoli Cui 2010 (24) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 9 |

| Hongbo Gao 2011 (25) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 6 | |||

| Tianyan Chen 2012 (26) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 9 |

| Jing Lai 2013 (12) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 8 | |

| Junshuai Wang 2014 (27) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | 9 |

a For cohort studies, 1 indicates exposed cohort truly representative; 2, non-exposed cohort drawn from the same community; 3, ascertainment of exposure; 4, outcome of interest not present at start; 5, cohorts comparable based on TBIL and PTA; 6, cohorts comparable on other factors; 7, quality of outcome assessment; 8, follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur; and 9, adequacy of follow-up of cohorts

The overall quality of included RCTs in this meta-analysis was suboptimal. None of four RCTs reported how the allocation sequences were generated. Three studies (11, 19, 20) did not report the methods of allocation concealment, and one study (18) took an open random allocation schedule. None of the trials referred to blinding method. Methodological quality of RCTs is shown in Table 2. Quality of included observational cohort studies was assessed, and each of the studies had at least six stars. Two studies (22, 25) did not describe the comparability of ETV and LAM groups. The study conducted by Jing Lai (12) recruited hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) negative patients with ACLF but not HBeAg positive patients, thus limiting the representative capacity of this study. Quality of retrospective studies is shown in Table 3.

4.2. Survival Comparison Between ETV and LAM Treatment Groups

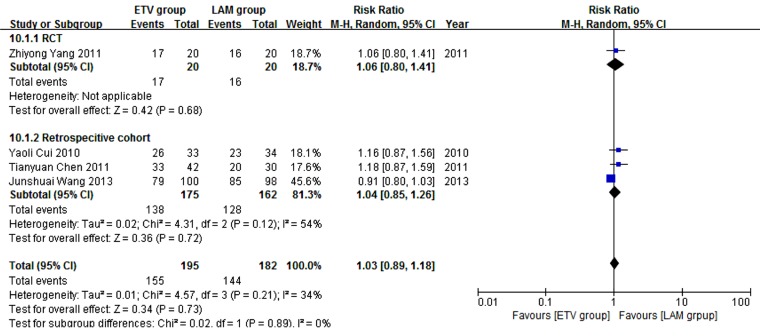

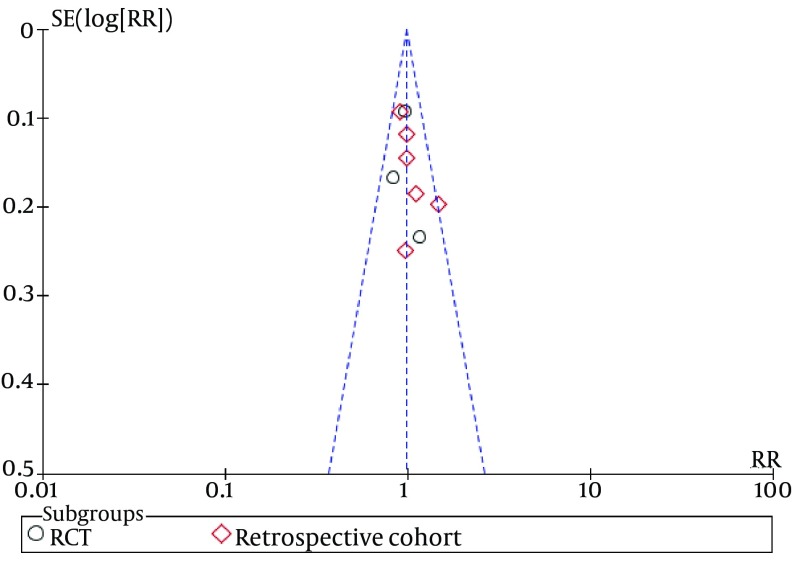

Four studies (19, 24, 26, 27) comprising 377 patients reported four weeks survival. One hundred and ninety five patients in the four studies used ETV and 182 used LAM. According to χ2 and I2 analyses, studies were significantly heterogeneous (χ2 = 4.57, P = 0.21 and I2 = 34%); therefore, random effect method was used to analyze data. Survival rates were comparable between the two treatment groups (79.5% versus 79.1%, RR = 1.03, 95% CI [0.89, 1.18], P = 0.73) (Figure 2). Subgroup analysis was also conducted. In RCT subgroup, survival rates were not significantly different between the ETV and LAM groups. In the retrospective cohort subgroup, survival rates were comparable between the two treatment groups (RR = 1.04, 95% CI [0.85, 1.26], P = 0.72).

Figure 2. Comparing Four Weeks Survival Between ETV and LAM Treatment Groups.

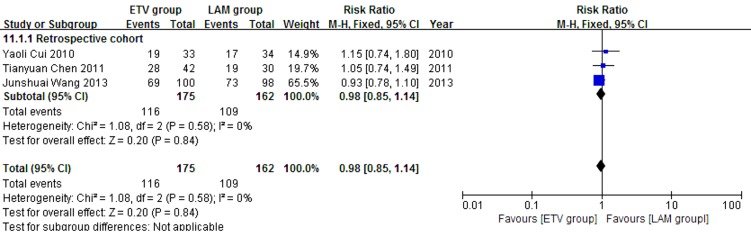

Three retrospective cohort studies (24, 26, 27) comprising 337 patients reported eight weeks survival. 175 patients in the three studies used ETV and 162 used LAM. These studies were not significantly heterogeneous (χ2 = 1.08, P = 0.58 and I2 = 0%); therefore, the fixed effect model was used to analyze the data. Survival rates were not significantly different between the two treatment groups (RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.85, 1.14], P = 0.84) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparing Eight Weeks Survival Between ETV and LAM Treatment Groups.

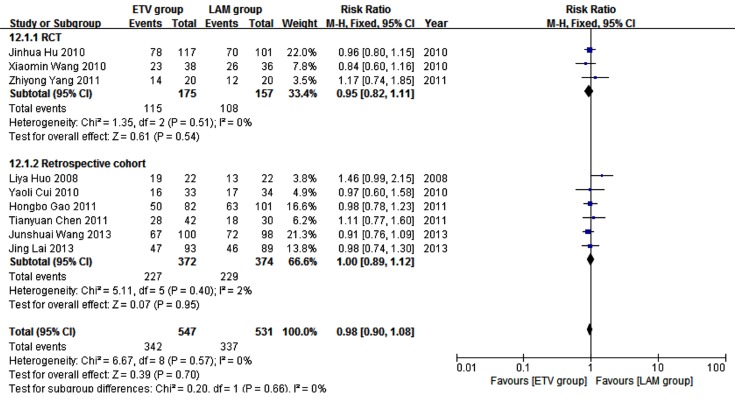

Nine studies (10, 12, 18-20, 24-27) comprising 1078 patients reported 12 weeks survival. In these studies, 547 patients received ETV, and 531 patients received LAM. In heterogeneity test, χ2 = 6.67, P = 0.57, and I2 = 0% (Figure 4), suggesting no significant variability among the included studies; therefore, the fixed effect model was used to analyze data. Survival rates were not significantly different between the two treatment groups (RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.90, 1.08], P =0.70). Subgroup analysis showed comparable survival rates between the two treatment groups in both the RCT and retrospective cohort subgroups (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Comparing Twelve Weeks Survival Between ETV and LAM Treatment Groups.

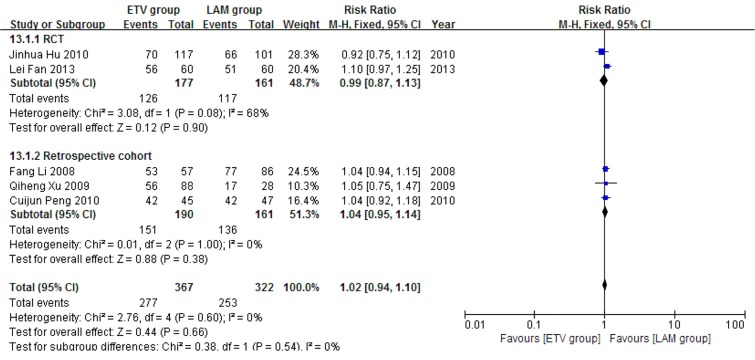

Five studies (11, 18, 21-23) comprising 689 patients reported 24 weeks survival. 367 patients in these studies received ETV and 322 patients received LAM. No heterogeneity was observed according to χ2 and I2 analyses, (χ2 = 2.76, P = 0.60 and I2 = 0%); therefore, the fixed effect method was used to analyze the data. Survival rates were comparable between the two treatment groups (RR = 1.02, 95% CI [0.94, 1.10], P = 0.66) (Figure 5). Subgroup analysis showed no significant difference in survival rates between the ETV and LAM treatment groups.

Figure 5. Comparing 24 Weeks Survival Between ETV and LAM Treatment Groups.

4.3. Comparing TBIL, PTA and HBV DNA Negative Change Rates Between ETV and LAM Treatment Groups

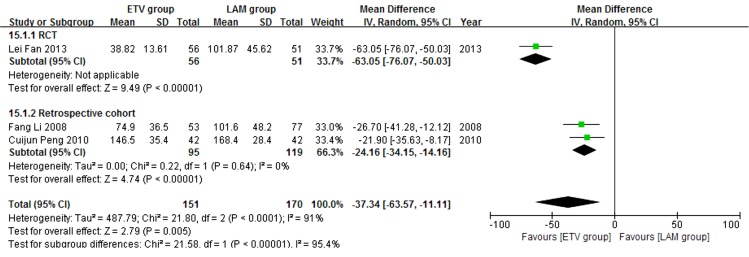

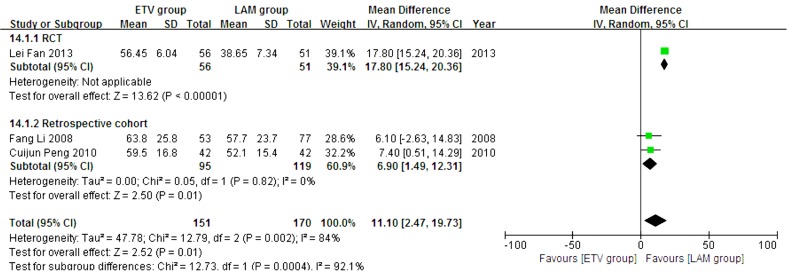

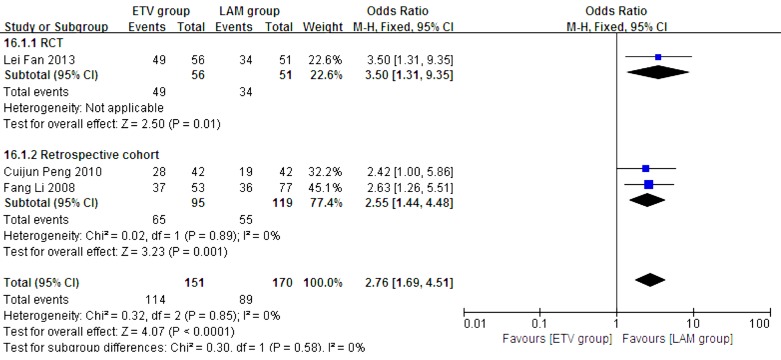

In this analysis, data regarding TBIL, PTA and HBV DNA negative change rates were available from only three studies (11, 21, 23). Patients in each of these studies were followed up for 24 weeks. We compared the impact of ETV and LAM on these indexes. Heterogeneity was analyzed using χ2 and I2 tests (TBIL: χ2 = 21.80, P < 0.0001 and I2 = 91%; PTA: χ2 = 12.79, P = 0.0002 and I2 = 84%; HBV DNA negative rate: χ2 = 0.32, P = 0.85 and I2 = 0%), and the fixed or random effect model was used depending on the absence or presence of significant heterogeneity. Our results showed that patients treated with ETV had significantly lower TBIL levels (MD = -37.34, 95% CI [-63.57, -11.11], P = 0.005) (Figure 6), higher PTA levels (MD = 11.10, 95% CI [2.47, 19.73], P = 0.01) (Figure 7) and higher HBV DNA negative rates (RR = 2.76, 95% CI [1.69, 4.51], P < 0.0001) (Figure 8) after 24 weeks treatment. Subgroup analysis showed that ETV was more effective than LAM to decrease HBV DNA level and improving liver function.

Figure 6. Comparing 24 Weeks TBIL Levels Between ETV and LAM Treatment Groups.

Figure 7. Comparing 24 Weeks PTA Levels Between ETV and LAM Treatment Groups.

Figure 8. Comparing 24 Weeks HBV DNA Negative Rates Between ETV and LAM Treatment Groups.

4.4. Safety

Of seven studies (10, 12, 18, 19, 22, 24, 26) reporting safety of ETV and LAM in treating CHB-associated liver failure, none reported drug-related adverse events or drug-related viral mutation.

4.5. Sensitivity Analysis

To confirm the stability of the primary analysis, we conducted sensitivity analysis using different statistical approaches (e.g. using the random effect model besides a fixed effect one); we also performed sensitivity analysis by excluding studies one by one. We found that results did not change significantly, suggesting the stability of this meta-analysis results.

4.6. Publication Bias

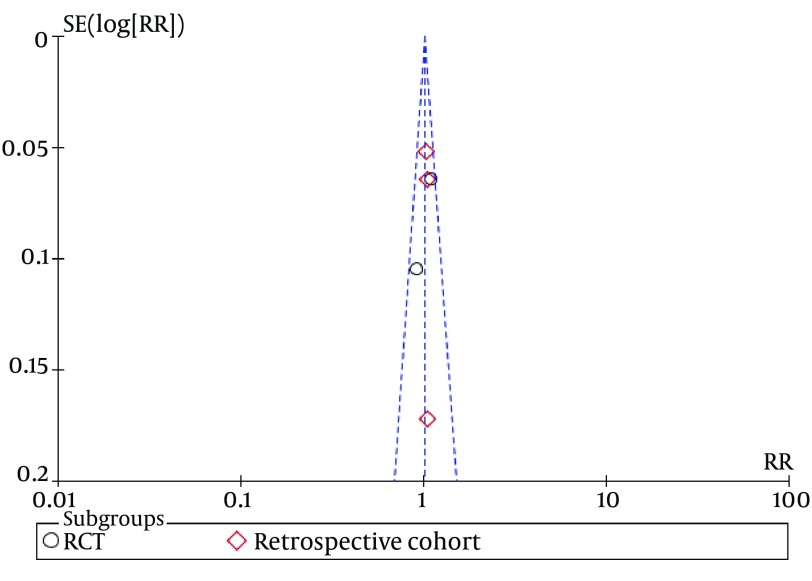

Funnel plots of studies used in this meta-analysis reporting 12 weeks and 24 weeks survival are shown in figures 9 and 10, respectively (Funnel plots for other survival time-points are not presented). None of the studies lay outside the limits of 95% CI. The trim and fill method analysis obtained the theoretical pooled estimate RR (12 weeks: RR = 0.86, 95% CI [0.68, 1.09], P = 0.20; 24 weeks: RR = 0.88, 95% CI [0.62, 1.24], P = 0.46) after theoretically unreported studies (3 and 3 for 12 and 24 weeks, respectively) were added and the results did not affect the outcome of the meta-analysis. Therefore, no evidence of publication bias was found in our study.

Figure 9. Funnel Plots for Studies Evaluating Twelve Weeks Survival.

Figure 10. Funnel Plots for Studies Evaluating 24 Weeks Survival.

5. Discussion

CHB-associated liver failure has a high mortality rate and is one of the most difficult to treat liver diseases. The disease mechanism is rather complicated and remained unclear. One of the important mechanisms is the high level of HBV replication and protein antigen expression on target cell surfaces, which often leads to an overactive immune response, especially the cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) reaction to infected hepatocytes. This mechanism is necessary for HBV clearance and causes significant apoptosis and necrosis of hepatocytes (28-30). Zhao’s study on the cause and outcome of chronic and acute liver failure showed that HBV replication and mutation were primary factors related to liver failure (31). Therefore, a reasonable solution for treating CHB-associated liver failure would be inhibiting HBV replication within the body and relieve immune hyperactivity using antiviral drugs. Many studies (26, 32-34) found that both ETV and LAM were effective to treat hepatitis B-associated liver failure. Patients treated with either of the two agents showed higher survivals, significant decrease of HBV DNA levels and higher clinical and biochemical responses compared to those not treated with any NA. As liver function is poor in patients with liver failure and the progression of disease is fast, selection of an appropriate antiviral drug in this setting is especially important. A study conducted by Sun QF showed that prognosis of patients with CHB-associated severe liver disease might be related to pretreatment HBV DNA load (35). Accordingly, it is possible that this group of patients would benefit from more potent anti-HBV drugs, which could decrease viral load more rapidly. ETV was demonstrated to be superior to LAM in suppressing HBV replication (36, 37). Therefore, it seems more reasonable to use ETV to treat patients with CHB-associated liver failure. In the present study, we included RCTs and observational cohort studies to compare the effects of ETV and LAM in patients with CHB-associated liver failure. Our data showed that patients treated with ETV had significantly lower TBIL levels, higher PTA levels and higher HBV DNA negative rates after 24 weeks of treatment. However, we found no significant difference between ETV and LAM to improve short-term survival. Interestingly, these results were consistent with a prior report conducted by Yaochun Hsu (38). In that study, 126 consecutive treat-naïve patients received either ETV (n = 53) or LAM (n = 73) for decompensated CHB. After one year of follow-up, effects of ETV and LAM on mortality rate were similar, but ETV was associated with greater clinical improvement among CHB survivors who recovered from hepatic decompensation. While explanations for discrepancy between laboratory improvement and survival benefits are currently unclear, insufficient sample sizes and inadequate observation periods are probable candidates. Besides, liver failure in some patients may already reach irreversibility beyond the rescue of viral suppression, and hence antiviral therapy would not affect short-term mortality in these patients.

Data comparing the efficacy of long-term treatment with ETV and LAM for patients with liver failure is lacking in the available literature, which might be due to severity of liver disease, poor prognosis of patients or high mortality rates restricting the continuation of long-term trials. There has been a particular concern for administration of ETV in patients with CHB-associated liver failure, because severe lactic acidosis during treatment of CHB with ETV occurred more often in patients with impaired liver function, especially in those with high MELD scores and multi-organ failure (13). However, in clinical trials for patients with decompensated liver disease due to CHB, lactic acidosis rarely occurred in ETV receivers and did not affect the safety profile compared to other NAs (39, 40). In our included studies, no severe adverse reactions were reported in the two treatment groups. Based on these data, we considered both ETV and LAM to be safe and tolerable for patients with HBV-related live failure. Our study had several limitations. First, total number of included trials was small, and some did not include all outcome parameters aimed to be analyzed in this study at different follow-up time points. Second, only four RCTs were included and the quality of these RCTs was suboptimal. Third, all included studies were conducted in China, so our conclusions might not be generalizable to other populations. Lastly, we restricted our research to articles published in full text, which might make us omit high-quality studies published in abstract form. It is suggested to assess high-quality, well-designed and multicenter RCTs with larger sample sizes in future studies. In conclusion, ETV and LAM had similar effects to improve 24 weeks survival rate for patients with CHB-associated liver failure, but ETV was associated with greater clinical improvement among those who survived. In addition, both ETV and LAM were well tolerated during the treatment. Further studies are needed to verify these results.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Jinan Infectious Disease Hospital. We thank Prof. Zhuangbo Mu (president of Jinan Infectious Disease Hospital) for his advice for this study. We also thank the members of Prof. Shijun Chen’s Laboratory for their helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions:Study conception and design: Shijun Chen and Yaguang Xi. Data acquisition and analysis: Xiaoguo Zhang, Yong An, Xuemei Jiang, Minling Xu and Linlin Xu. Writing of the paper: Xiaoguo Zhang. Critical revision: Shijun Chen and Yaguang Xi. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding/support:This work was supported by Jinan Infectious Disease Hospital.

References

- 1.Zhang C, Zhong Y, Guo L. Strategies to prevent hepatitis B virus infection in China: immunization, screening, and standard medical practices. Biosci Trends. 2013;7(1):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chinese Society of H, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases CMA. [The guideline of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B (2010 version)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2011;19(1):13–24. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50(3):661–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization Committee of 13th Asia-Pacific Congress of Clinical M, Infection. 13th Asia-Pacific Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infection Consensus Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of liver failure. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12(4):346–54. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(13)60055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assiciation CM. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of liver failure. Chin J Clin Infect Dis. 2012;5(6):321–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association CM. Diagnostic and treatment guidelines for liver failure. Chin J Hepatol. 2006;14(9):643–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, Chawla YK, Fan ST, Garg H, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver (APASL). Hepatol Int. 2009;3(1):269–82. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9106-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee WM, Stravitz RT, Larson AM. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Position Paper on acute liver failure 2011. Hepatology. 2012;55(3):965–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.25551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tillmann HL, Zachou K, Dalekos GN. Management of severe acute to fulminant hepatitis B: to treat or not to treat or when to treat? Liver Int. 2012;32(4):544–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huo L. Effect of entecavir in patients with chronic severe hepatitis B. J Xinxiang Med Coll. 2008;25(5):482–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lei F. The treatment effect of enticavir on chronic severe hepatitis B. Med Front. 2013;8:7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai J, Yan Y, Mai L, Zheng YB, Gan WQ, Ke WM. Short-term entecavir versus lamivudine therapy for HBeAg-negative patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12(2):154–9. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(13)60025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lange CM, Bojunga J, Hofmann WP, Wunder K, Mihm U, Zeuzem S, et al. Severe lactic acidosis during treatment of chronic hepatitis B with entecavir in patients with impaired liver function. Hepatology. 2009;50(6):2001–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.23346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong VW, Wong GL, Yiu KK, Chim AM, Chu SH, Chan HY, et al. Entecavir treatment in patients with severe acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2011;54(2):236–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Association CM. National viral hepatitis control programme. Chin J hepatol. 2000;8(6):324–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2014 Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 17.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu JH, Wang HF, He WP, Liu XY, Du N, Huang K, et al. [Lamivudine and entecavir significantly improved the prognosis of early-to-mid stage hepatitis B related acute on chronic liver failure]. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi. 2010;24(3):205–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhiyong Y, Dongxia L, Ni W. Observation of efficacy and safety of entecavir in treatment of liver failure. Mod Chin Dr. 2012;50(14):71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X. The effects of entecavir and lamivudine for patients with chronic severe hepatits b. Chin Mod Med. 20;17(34):62–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang L, Chen T, Jiangxia D. The short-term clinical effect of entecavir in the treatment of patients with chronic severe hepatitis B. J Clin Hepatol . 2008;11(6):383–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu QH, Chen LB, Xu Z, Shu X, Chen N, Cao H, et al. [The short-term efficacy of antiviral treatment in patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure]. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi. 2009;23(6):467–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuijun P, Wenqiu L, Ying Z. Entecavir for chronic severe viral hepatitis B: clinical observation of 45 cases. Progress in Modern Biomedicine. Prog Mod Biomed. 2010;10(24):4735–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui YL, Yan F, Wang YB, Song XQ, Liu L, Lei XZ, et al. Nucleoside analogue can improve the long-term prognosis of patients with hepatitis B virus infection-associated acute on chronic liver failure. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(8):2373–80. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hongbo G, Min X, Haiyan S, Yueping L, Lei X. Clinical analysis of antiviral treatment in chronic severe hepatitis B with HBVDNA positive. Chin J Integr Tradit West Med Liver Dis. 2011;21(6):330–2. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen T, He Y, Liu X, Yan Z, Wang K, Liu H, et al. Nucleoside analogues improve the short-term and long-term prognosis of patients with hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure. Clin Exp Med. 2012;12(3):159–64. doi: 10.1007/s10238-011-0160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Ma K, Han M, Guo W, Huang J, Yang D. Nucleoside analogs prevent disease progression in HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure: Validation of the TPPM model. Hepatol Int. 2014;8(1):64–71. doi: 10.1007/s12072-013-9485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rolando N, Wade J, Davalos M, Wendon J, Philpott-Howard J, Williams R. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome in acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2000;32(4 Pt 1):734–9. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.17687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Jiang D, Zhang H, Lv S, Rao H, Fei R, et al. Proteome responses to stable hepatitis B virus transfection and following interferon alpha treatment in human liver cell line HepG2. Proteomics. 2009;9(6):1672–82. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoofnagle JH, Doo E, Liang TJ, Fleischer R, Lok AS. Management of hepatitis B: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 2007;45(4):1056–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.21627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Z, Han T, Gao Y, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Wu Z. Analysis on the predisposing cause and outcome of 289 cases of hepatitis B patients complicated with chronic or acute liver failure. World J Gastroenterol . 2009;17:3269–72. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma K, Guo W, Han M, Chen G, Chen T, Wu Z. Entecavir treatment prevents disease progression in hepatitis B virus-related acute-on-chronic liver failure: Establishment of a novel logistical regression model. Hepatol Int. 2012;6(4):735–43. doi: 10.1007/s12072-012-9344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin B, Pan CQ, Xie D, Xie J, Xie S, Zhang X. Entecavir improves the outcome of acute-on-chronic liver failure due to the acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Int. 2013;7(2):460–7. doi: 10.1007/s12072-012-9415-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun LJ, Yu JW, Zhao YH, Kang P, Li SC. Influential factors of prognosis in lamivudine treatment for patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(3):583–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun QF, Lu Y, Xu DZ, Lan XY, Liu JY, Sun XJ. The impact of HBeAg positivity/negativity and HBV DNA loads on the prognosis of chronic severe hepatitis B. Chin J Hepatol. 2006;14(6):410–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai CL, Shouval D, Lok AS, Chang TT, Cheinquer H, Goodman Z, et al. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(10):1011–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao YC, et al. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(10):1001–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsu YC, Mo LR, Chang CY, Perng DS, Tseng CH, Lo GH, et al. Entecavir versus lamivudine in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B patients with hepatic decompensation. Antivir Ther. 2012;17(4):605–12. doi: 10.3851/IMP2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liaw YF, Sheen IS, Lee CM, Akarca US, Papatheodoridis GV, Suet-Hing Wong F, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), emtricitabine/TDF, and entecavir in patients with decompensated chronic hepatitis B liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53(1):62–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.23952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liaw YF, Raptopoulou-Gigi M, Cheinquer H, Sarin SK, Tanwandee T, Leung N, et al. Efficacy and safety of entecavir versus adefovir in chronic hepatitis B patients with hepatic decompensation: a randomized, open-label study. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):91–100. doi: 10.1002/hep.24361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]