Abstract

We analyzed the correlation between survival and antitumor effect evaluated by RECIST in advanced NSCLC patients with chemotherapy plus target therapy or not as first-line treatment, to examine the applicability of RECIST in this population. The patients were screened from 4 clinical trials (12621, 12006, FASTACT-I, and FASTACT-II), and those who received chemotherapy plus target therapy or chemotherapy alone were eligible. Among the 59 enrolled patients, 29 received combination therapy, while the other 30 received chemotherapy only. In the combination therapy group, patients with PR or SD had longer overall survival (OS) than those with PD (P < 0.001 and P = 0.002, respectively). However, in the chemotherapy alone group, compared with PD patients, either PR or SD group had no significant overall survival benefit (P = 0.690 and P = 0.528, respectively). In summary, for advanced NSCLC patients receiving chemotherapy plus target therapy as first-line treatment and evaluated by RECIST criteria, SD has the same overall survival benefit as PR, suggesting that antitumor effective evaluation by RECIST criteria cannot be translated to overall survival benefit especially for this kind of patients. Therefore, developing a more comprehensive evaluation method to perfect RECIST criteria is thus warranted for patients received target therapy in NSCLC.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the world, about 85% cases of which are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Appropriately 25% of NSCLC patients possess local advanced disease, and 40% have metastatic disease at initial diagnosis; systemic chemotherapy has been the main therapeutic method for these patients1. However, the standard cytotoxic chemotherapy of platinum-based doublet has reached the therapeutic bottleneck, with an OS of about 10 months and one-year survival rate at 35%2. Recent successful development of targeted therapy has greatly improved the survival of NSCLC patient population and changed the therapeutic situation to a large extent. These agents include angiogenesis inhibitors, tumor cell apoptosis inducers, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs)3,4, which have been widely used in advanced NSCLC.

In recent years, the combination therapy of cytotoxic drugs with target agents, especially the small-molecular tyrosine kinase inhibitors, has been studied as the first-line treatment. A phase III study (INTACT 2) confirmed the safety of Gefitinib plus paclitaxel and carboplatin in chemotherapy- naive patients with advanced NSCLC5. Besides, a phase II trial of sequential combination of erlotinib and chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced NSCLC showed a significant improvement in PFS6, which was further confirmed by the FASTACT-II study7. Now this model of combination therapy has become a promising option for the management of advanced cancers.

In clinical trials and practice using chemotherapy, RECIST has been widely used to identify and quantify the antitumor activity of new agents, providing a relatively quick assessment of efficacy. The treatment effect was usually evaluated as PR (≥30% decrease in the sum of diameter of target lesions), PD (≥20% increase in the sum of diameter of target lesion), SD (<20% increase in the sum of diameter of target lesion or <30% decrease in them). However, many anticancer drugs especially the target agents show their main antitumor effect as slowing down or inhibiting the growth of tumor volume rather than decreasing it; Therefore, it is uncommon to observe marked shrinkage of tumor on the imaging. It has been found that the objective response rate of target agents has not always been corresponding with the clinical benefit. For example, in a phase II clinical trials assessing the efficacy of bevacizumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma, the response was only 10–13%8, but the subsequent phase III clinical trial demonstrated that the PFS in bevacizumab group was significant longer than that in placebo (4.8 months vs. 2.5 months, HR = 0.39, P < 0.001)9. Moreover, our previous study indicated that although SD patients showed no significant difference from PR group (P = 0.528), the PFS (5.56 months vs. 2.03 days, P < 0.001) and OS (12.2 months vs. 7.1 months, P < 0.001) of SD+ patients were significantly shorter than those of SD-/0 patients10. Hence, many specialists recommended the disease control rate (DCR), rather than response rate for clinical evaluation of target agent in research. However, there is still lack of special study on the assessment of combination of target therapy and chemotherapy.

Therefore, the present study aimed to analyze the correlation of objective response evaluated by RECIST with patient survival in advanced NSCLC patients who received combination of target therapies and chemotherapy or chemotherapy alone from 4 independent clinical trials, in order to ultimately provide a better management for advanced cancer patients.

Results

Of the 59 patients evaluated, 29 received combination of target therapy and chemotherapy, while the other 30 received only chemotherapy. As shown in Table 1, 31 patients were evaluated as PR (52.5%); 22 had a best evaluation of SD (37.3%), and 6 were evaluated as PD (10.2%). The median PFS for this series of 59 patients was 6.9 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.13–8.73), and the median OS was 22.8 months (95% CI, 19.13–26.41).

Table 1. Characteristics of all patients.

| Characteristics | Cases (n = 59) | Percentage(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | ||

| Median | 57(27–78) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 38 | 64.4 |

| Female | 21 | 35.6 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never-smoker | 29 | 48.3 |

| Smoker | 31 | 51.7 |

| Histological feature of tumor | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 49 | 83.1 |

| Nonadenocarcinoma | 10 | 16.9 |

| Disease stage | ||

| IIIB | 5 | 8.5 |

| IV | 54 | 91.5 |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 17 | 28.8 |

| 1 | 42 | 71.2 |

| Response | ||

| PR | 31 | 52.5 |

| SD | 22 | 37.3 |

| PD | 6 | 10.2 |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

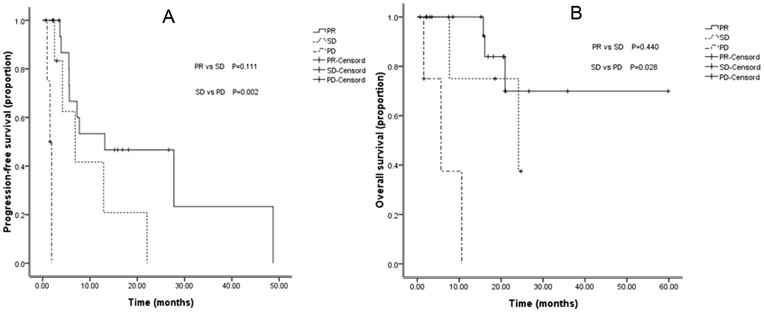

In the 29 patients who received both target therapy and chemotherapy (9 patients from 12006: GP + Sorafenib; 8 patients from 12621: TC + Sorafenib; 5 patients from FASTACT-I: GP/GC + Tarceva; and 7 patients from FASTACT-II: GP/GC + Tarceva), 16 with best evaluation of PR; 9 with best response of SD, and the rest 4 patients had a response of PD. Among these 29 patients, there was no significant difference between the PR and SD groups with respect to PFS (P = 0.111) and OS (P = 0.440). However, in comparison with the PD group, significant differences were found between the PR and PD groups in PFS (P < 0.001) and OS (P < 0.001). The patients with SD also exhibited a longer PFS (P = 0.002) and OS (P = 0.028) compared with PD patients (Table 2 and Figure 1). Moreover, patients with disease control (PR + SD) achieved significant longer PFS and OS compared to those with PD (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively).

Table 2. Correlation between different response and the PFS in patients treated with target therapy and chemotherapy (n = 29).

| Items | PFS (months) (95% CI) | Univariate analysis P* | Median survival (months) (95% CI) | Univariate analysis P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PR | 13.1(0.0–27.3) | 0.111 | - | 0.440 |

| SD | 6.9(1.2–12.5) | 24.1(0.0–48.8) | ||

| 2. PR + SD | 12.9(4.4–21.4) | <0.001 | - | <0.001 |

| PD | 1.5(0.9–2.2) | 5.7(0.0–11.8) | ||

| 3. SD | 6.9(1.2–12.5) | 0.002 | 24.1(0.0–48.8) | 0.028 |

| PD | 1.5(0.9–2.2) | 5.7(0.0–11.8) | ||

| 4. PR | 13.1(0.0–27.3) | <0.001 | - | <0.001 |

| PD | 1.5(0.9–2.2) | 5.7(0.0–11.8) |

Note:*Log-Rank test.

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence interval; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Figure 1.

PFS and OS curves for patients received both target therapy and chemotherapy with different response: (A) Comparison of PFS among patients with PR, SD, and PD.(B) Comparison of OS among patients with PR, SD, and PD.

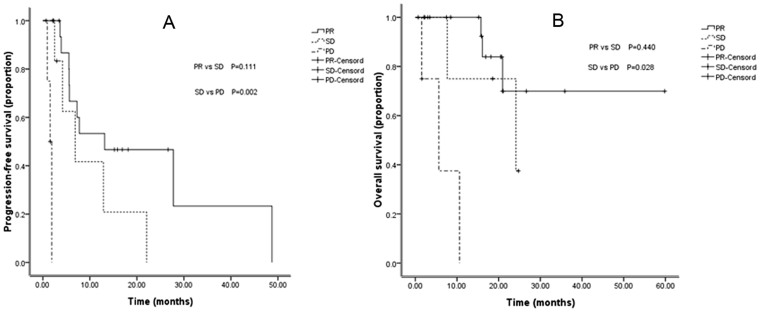

Among the other 30 patients treated with chemotherapy alone (9 from GP group in 12006, 5 from TC group in 12621, 4 from GP/GC group in FASTACT-I, and 6 from GP/GC group in FASTACT-II), 15 had tumor regression more than 30%, 13 had tumor regression less than 30%, and the rest patients had tumor enlargement more than 20%. Comparing with SD group, the patients with PR had no obvious survival benefit (P = 0.588); however, the PFS of the latter was significantly longer than that of the PD (P = 0.010) and SD (P < 0.001) patients. Nevertheless, neither PR group nor SD group showed longer OS compared with PD group, which was different from the results of combined target therapy and chemotherapy (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Table 3. Correlation between different response and the PFS in patients treated with chemotherapy (n = 30).

| Items | PFS (months) (95% CI) | Univariate analysis P* | Median survival (months) (95% CI) | Univariate analysis P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PR | 5.0(3.0–6.9) | 0.136 | 27.8(-) | 0.588 |

| SD | 6.9(6.3–7.5) | 22.1(8.5–35.8) | ||

| 2.PR + SD | 6.8(4.3–9.3) | <0.001 | 22.1(8.5–35.8) | 0.564 |

| PD | 0.8(-) | 13.3(-) | ||

| 3.SD | 6.9(4.7–9.2) | <0.001 | 22.1(8.5–35.8) | 0.528 |

| PD | 0.8(-) | 13.3(-) | ||

| 4.PR | 5.0(3.4–6.9) | 0.010 | 27.8(-) | 0.690 |

| PD | 0.8(-) | 13.3(-) |

Note:*Log-Rank test.

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence interval; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Figure 2.

PFS and OS curves for patients received chemotherapy only with different response: (A) Comparison of PFS among patients with PR, SD, and PD.(B) Comparison of OS among patients with PR, SD, and PD.

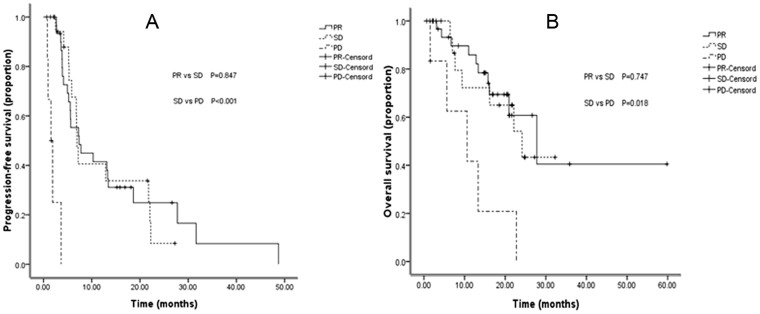

The correlation between the response to therapy and the survival was examined using univariate analysis. The median survival time of PR, SD, and PD groups was 27.8, 24.1, and 10.6 months, respectively, while the corresponding median PFS was 7.4, 6.9, and 1.5 months, respectively. Of the 59 evaluated patients, comparing with PD patients, the ones with disease control (PR + SD) showed obvious survival benefit (P = 0.001) (Table 4). In further comparison, the PFS of both PR and SD groups were significantly longer than that of the PD group (both P < 0.001). The PR and SD groups also showed a longer survival time compared with PD group (P = 0.002 and P = 0.018, respectively. There were no significant difference in OS (P = 0.847) and PFS (P = 0.747) observed between PR and SD groups (Figure 3).

Table 4. Correlation between different response and the PFS in whole series of NSCLC patients (n = 59).

| Items | PFS (months) (95% CI) | Univariate analysis P* | Median survival (months) (95% CI) | Univariate analysis P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PR | 7.4(3.7–11.0) | 0.847 | 27.8(15.7–39.9) | 0.747 |

| SD | 6.9(6.4–7.4) | 24.1(13.2–35.1) | ||

| 2. PR + SD | 7.3(6.1–8.4) | <0.001 | 27.8(20.0–35.6) | 0.001 |

| PD | 1.5(0.6–2.5) | 10.6(0.3–21.0) | ||

| 3. SD | 6.9(6.4–7.4) | <0.001 | 24.1(13.1–35.2) | 0.018 |

| PD | 1.5(0.6–2.5) | 10.6(0.3–21.0) | ||

| 4. PR | 7.4(3.7–11.0) | <0.001 | 27.8(15.7–39.9) | 0.002 |

| PD | 1.5(0.6–2.5) | 10.6( 0.3–21.0) |

Note:*Log-Rank test.

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence interval; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Figure 3.

PFS and OS curves for the 59 patients with different response after therapy: (A) Comparison of PFS among patients with PR, SD, and PD. (B) Comparison of OS among patients with PR, SD, and PD.

The results of the univariate analysis of the correlation between clinical characteristics and prognosis of the 59 patients revealed that there were no statistically significant correlation between the prognosis and the smoking history (P = 0.421), age (P = 0.482), and pathological type (P = 0.209).

Discussion

We have retrospectively analyzed the correlation of therapeutic efficacy evaluated by RECIST with the patient survival in 4 clinical trials with target agents. Among the total 59 patients evaluated, PR and SD groups had similar PFS and OS, which was consistent with the population receiving combination therapy. Based on this, our research firstly analyzed the correlation between objective response and survival after combination treatment of chemotherapy with target therapy.

Target therapy aims to inhibit the growth of tumor, which is different from the killing-effect of cytotoxic drugs. The molecular-targeted therapies available for lung cancer are more likely to result in SD than to produce tumor regression. Our previous study10 reported EGFR-TKI for advanced NSCLC, with survival benefit observed in patients with tumor stabilization. Kurata et al.11 demonstrated that 1% increase in DCR would prolong the survival time by 0.0375 months in advanced NSCLC patients receiving EGFR-TKI as second-line therapy. About 67% phase II and phase III clinical trials for target therapy take DCR (CR + PR + SD), other than objective response rate, as primary objective12. We also found the same results in the chemo and target therapy queue, SD patients had no difference with PR patients in OS (P = 0.440) and PFS (P = 0.111). However, both PR and SD patients had better survival benefit than PD patients (P < 0.001 and P = 0.028, respectively), indicating that the SD patients also obtained survival benefit from the combination of chemo and target therapy or target therapy only. This information suggested that DCR may be a better endpoint than response rate in this kind of clinical study, to avoid missing a good antitumor drug. Moreover, better criteria should be explored in the evaluation of combination of target and chemotherapy.

In the chemotherapy queue, overwhelming superiority of SD and PR patients over PD patients was observed in PFS (P < 0.001 and P = 0.010, respectively); however, there was no difference in OS between (PR + SD) group and PD group (P = 0.564), which was different from the present study13. The possible reasons for this may include the small sample size, which had no enough power to distinguish the difference in survival between patients with disease control and PD. Besides, the subsequent therapies are confounding factors of OS, which may counteract the difference of OS between groups.

In our study, the median survival of target combined with chemotherapy group was 15.9 months, which was much longer than 2 phase II trials of first-line EGFR-TKI in unselected patients with advanced NSCLC14,15. All patients in this group had received chemotherapy, which enhanced the killing effect on tumor cells to certain extent. In terms of the killing-effect of chemotherapy, in the 22 patients evaluated with SD, only 1 patient had slight tumor enlargement, while the other 21 had tumor regression, which is different from the result of our previous report that 13 out of the 40 patients in SD group had slight tumor enlargement10. The median survival of chemotherapy group was 14.1 months, much longer than the result of other studies, possibly due to a subsequent treatment.

At present, OS is considered to be the most important indicator of clinical efficacy endpoints for therapy regimen, but it requires prolonged follow-up and is often affected significantly by other factors, such as subsequent treatment. Therefore, OS may lead to either a waste of the medical resources or a loss of the benefit from maintained therapy. Therefore, a more effective parameter is needed to guide the choice of treatment during the course of disease. In oncology, change in tumor size is linked to survival in some solid tumors. Bruno et al. suggested that change in tumor size can be used as a primary endpoint in the design and evaluation of phase II studies and in supporting go/no-go decisions and phase III study design16. Kris also indicated that any increase or decrease of tumor size should be taken as a surrogate endpoint for efficacy17. Many analyses showed that the change of tumor size was an independent prognostic factor. We also found that SD patients with tumor regression had significant survival benefit. He et al. suggested that initial PR and SD patients with advanced NSCLC enjoy similar PFS and OS18. These results suggest that response rate may be not a suitable indicator to define the evaluation of antitumor treatment.

The World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, evaluating the effect of treatment by comparing the sum of the products of bidimensional lesion measurement, were a reliable norm in assessing the effectiveness of chemotherapy for patients with advanced NSCLC. However, after 20 years of practice, we found that the criteria remained to be improved. The measurable, evaluable lesions were not defined, and estimating the tumor size by the product of the longest diameter and its vertical length caused inaccuracy of the result. Thus the EORTC, NCI, and NCIC put forward the RECIST, which was also based on the morphological features of tumor, but used the unidimensional lesion measurement, defining both the measurable lesions and the number of target lesions, making a great progress when compared to the WHO criteria19,20. Therefore, in both clinical trials and practice, the RECIST became a standard for evaluation of efficacy. However, limitations remained in RECIST criteria, which is especially true when dealing with the targeted therapy. Ours and several other studies have verified that patients with SD have been also benefited from the continuation of the original treatment17.

Several limitations need to be considered. The sample size of the present study is small, and this is a retrospective study; all the patients with advanced NSCLC were from 4 clinical trials enrolled in one center. Moreover, in the field of combinatorial chemotherapy and target therapy, a limited number of the clinical trials are available, so we were unable to enroll more patients into this study. However, these patients were initially enrolled under strict inclusion criteria and received treatment in a standard way with a long follow-up, and the imaging evaluation was performed by a systematical radiologic review committee. Therefore, the results of the present study could still provide important information.

Our study showed that in patients with chemotherapy plus target agents as first-line treatment, under evaluation with RECIST criteria, SD patients had the same overall survival benefit as PR patients. Moreover, when compared with PD group, patients with disease control (PR + SD) had longer survival. However, in the chemotherapy alone group, there was no significant difference between disease control group and PD group. These findings indicated that RECIST criteria may not reflect the change of tumor cell viability timely to fully reliably predict patient's prognosis, especially for advanced NSCLC patients receiving chemotherapy plus target therapy as first-line treatment. Therefore, a more comprehensive evaluation method is thus needed to evaluate therapeutic efficacy in this population. Prospective randomized studies with advanced NSCLC patients are required to further validate the present results.

Methods

Patients

Patients with stage IIIB or IV NSCLC were enrolled in 4 clinical trials (FASTACT-I study, FASTACT-II study, 12621 study, and 12006 study); among them the ones who received targeted therapy (Tarceva or Sorafenib) combining with chemotherapy or chemotherapy alone as first-line treatment in Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center from September, 2006 to August, 2011, were retrospectively analyzed. The criteria for eligibility were as follows: 1) histologically- or cytologically-confirmed stage IIIB or IV NSCLC, 2) an age of at least 18 years, 3) an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1, 4) having at least one measurable lesion, 5) possessing adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function, and 6) having a life expectancy of at least 3 months. Prior radiation therapy was permitted, if the indicator sites (the sites that were followed to determine whether there was a response) had not been irradiated, and the radiation therapy had been completed at least 4 weeks before the enrollment. Patients who had received systemic treatment, including target therapy, chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 4 weeks of study were excluded; patients with brain metastases were ineligible for the studies. All patients provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center. All the methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines from Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center.

Of the 64 patients enrolled, 4 patients in the 12006 study even had not completed a cycle treatment, and 1 patient dropped out after 1 cycle treatment due to AE in the 12621 study. A total of 59 patients were finally evaluated, with 21 females and 38 males. The median age was 57 years (range, 27–78 years). The clinical characteristics of the patients in the 4 clinical trials were similar (Table 1).

Treatment

In the 12621 study, patients received 175 mg of paclitaxel per square meter of body-surface area and carboplatin at a dose calculated to produce an AUC (area under the concentration–time curve) of 5 mg per milliliter per minute on day 1, and 400 mg Sorafenib/placebo on day 1–21. The cycle was repeated every 3 weeks. In the 12006 study, patients treated with gemcitabine, at a dose of 1250 mg per square meter of body-surface area (administered on day 1 and 8), 75 mg of cisplatin per square meter of body-surface area (administered on day 1), and Sorafenib/placebo 400 mg twice per day, for a cycle of 3 weeks. In both studies patients continued to receive Sorafenib or placebo until progression or unacceptable toxicity or death after 3 cycles of treatment. Patients were administered 6 cycles of gemcitabine at a dose of 1250 mg per square meter of body-surface area on days 1 and 8, followed by cisplatin at a dose of 75 mg per square meter of body-surface area or carboplatin 5× AUC on day 1, and with intercalated Tarceva/placebo 150 mg/day on days 15–28 every 4 weeks both in the FASTACT-I/II study. In the same way, patients continued to receive Tarceva or placebo until progression or unacceptable toxicity or death, and all patients in the placebo group were offered second-line Tarceva at the time of progression. We analyzed all the evaluable patients in these 4 trials. Among the 13 patients from 12621 study, 8 received GP and Sorafenib, while others received GP and placebo. Of the 24 patients from 12006 study, 9 were treated with GP and Sorafenib, and the remaining ones received GP and placebo. Among the 9 patients from FASTACT-I study, 5 received GP/GC and Tarceva, and 4 received GP/GC and placebo. The rest 13 patients were from FASTACT-II study; 7 of them received GP/GC and Tarceva, and the other 6 received GP/GC and placebo.

Tumor response evaluation

The target lesion was assessed with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at baseline within 4 weeks before randomization. RECIST (version 1.0) evaluation of therapeutic effect was based on tumor assessment with follow-up, including chest and upper-abdominal CT scan every 2 cycles of treatment or every 6 weeks until disease progression or death. Besides, the method of assessment was exactly the same as that in the corresponding clinical trials, and the imaging evaluation was performed by an independent radiologic review committee. The designations of CR, PR, SD, and PD were on the basis of the standardized response definitions established by the RECIST. CR was defined as the disappearance of all target lesions. Any pathological lymph nodes (whether target or non-target) must have reduction in short axis to <10 mm. PR was defined as at least a 30% decrease in the sum of diameter of target lesions, taking the baseline sum diameters as reference. SD referred to a change of lesion size ranging from an increase of <20% to a decrease of <30% and with no new lesion. PD was defined as at least a 20% increase in the sum of diameter of target lesions, taking the smallest sum on study as reference.

Statistical analysis

We calculated 95% CI for PFS and OS outcomes to assess the treatment efficacy. Kaplan–Meier method was used to describe PFS and OS. All reported time-to-event comparisons were conducted using the log-rank test analysis respectively. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS 17.0 software was used for all statistical analysis (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Follow-up

The 59 patients received CT scan every 6 weeks until disease progression or death according to the criteria of these 4 clinical trials. They were also asked to answer questionnaire like quality of life (QoL) every 6 weeks at the clinic or on the phone. We compared the difference of patients' survival by means of PFS and OS. PFS was calculated from the date of randomization to disease progression (local or metastatic) or death for any reason. OS was defined as the time elapsed from the date of randomization to the time of death for any cause. Patients who had not progressed or died at the time of statistical analysis were censored at the time of last follow-up.

Author Contributions

Z.T. wrote manuscript and analyzed data; Z.L. performed research and analyzed data; Z.H.Y. and Z.L. designed research and performed research; H.Z.H. and F.W.F. analyzed data; G.J.Y., Z.Y.Y. and Z.Y. performed research.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by provincial science and technology fund in 2009 (303040791002).

References

- Novello S. & Le Chevalier T. Chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. Part 2: Advanced disease. Oncology (Williston Park) 17, 457–471 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis S. H., Murray T., Bolden S. & Wingo P. A. Cancer statistics, 1999. CA Cancer J Clin 49, 8–31, 31 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal C., Somaiah N. & Simon G. Antiangiogenic agents in the management of non-small cell lung cancer: where do we stand now and where are we headed? Cancer Biol Ther 13, 247–263, 10.4161/cbt.19594 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger D. S. et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 2.2013. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 11, 645–653, quiz 653 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst R. S. et al. Gefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial–INTACT 2. J Clin Oncol 22, 785–794, 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok T. S. et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II study of sequential erlotinib and chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 27, 5080–5087, 10.1200/jco.2008.21.5541 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. L. et al. Intercalated combination of chemotherapy and erlotinib for patients with advanced stage non-small-cell lung cancer (FASTACT-2): a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet Oncol 14, 777–786, 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70254-7 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. C. et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med 349, 427–434, 10.1056/NEJMoa021491 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler A. et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 355, 2542–2550, 10.1056/NEJMoa061884 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. The impact of tumor size change after target therapy on survival: analysis of patients enrolled onto three clinical trials of advanced NSCLC from one institution. Onco Targets Ther 5, 349–355, 10.2147/OTT.S38441 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata T. et al. Is the importance of achieving stable disease different between epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors and cytotoxic agents in the second-line setting for advanced non-small cell lung cancer? J Thorac Oncol 1, 684–691 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J. K. et al. Analysis of phase II studies on targeted agents and subsequent phase III trials: what are the predictors for success? J Clin Oncol 26, 1511–1518, 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8874 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAleer M. F. et al. Does response to induction chemotherapy predict survival for locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer? Secondary analysis of RTOG 8804/8808. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 76, 802–808, 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.053 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reck M. et al. Gefitinib monotherapy in chemotherapy-naive patients with inoperable stage III/IV non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 7, 406–411 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaccone G. et al. Erlotinib for frontline treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase II study. Clin Cancer Res 12, 6049–6055, 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0260 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno R. & Claret L. On the use of change in tumor size to predict survival in clinical oncology studies: toward a new paradigm to design and evaluate phase II studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther 86, 136–138, 10.1038/clpt.2009.97 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kris M. G. Foreword; challenging the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 60 Suppl 2S1–2, 10.1016/S0169-5002(08)70098-9 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L. et al. Initial partial response and stable disease according to RECIST indicate similar survival for chemotherapeutical patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 10, 681, 10.1186/1471-2407-10-681 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. O. et al. Measuring response in solid tumors: comparison of RECIST and WHO response criteria. Jpn J Clin Oncol 33, 533–537 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi K. et al. [CT evaluation of response to chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy in primary lung cancer: comparison of response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) and the WHO criteria, and comparison of both methods with the histological evaluation]. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi 64, 41–45 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]