Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) screening guidelines for hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients are not well defined. Retrospective assessment of standardized pre-transplant MRSA screening in a large single center cohort of HCT recipients demonstrated that colonization was uncommon, and that no colonized patients developed post-transplant invasive complications.

Keywords: Hematopoietic cell transplant, MRSA, Screening

INTRODUCTION

Hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients are at increased risk for infections, so screening for certain high-risk pathogens is recommended.1 Although research on the prevalence and prevention of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) exists in other vulnerable populations,2 data on MRSA carriage, screening, and associated morbidity and mortality in this population are limited.3,4 National HCT guidelines do not offer recommendations for routine screening for MRSA carriage,1 as unlike vancomycin-resistant enterococci,5 no studies have demonstrated associations between pre-transplant carriage and post-transplant infections.

At our center, Infection Prevention (IP) policy requires screening of all HCT recipients for MRSA nasal carriage upon arrival. Using a retrospective cohort design, we assessed the prevalence of MRSA colonization detected from this screening program over 5 years, and explored relationships between nasal carriage and post-transplant MRSA complications. These data are some of the first to assess standardized pre-transplant MRSA screening in HCT recipients.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective single center cohort study of adults undergoing HCT between 1/1/2008 and 12/31/2012. All HCT recipients underwent a pre-transplant evaluation that included screening cultures for MRSA nasal carriage; swabs were cultured on MRSA chromogenic media (Spectra™ MRSA, Fisher Scientific, Lenexa, KS). Demographic data were retrieved from a prospectively collected center database and medical record review. Antimicrobial prophylaxis was administered as described elsewhere.6 Chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) impregnated dressings (Biopatch®, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ; Tegaderm™, 3M, St. Paul, MN) were applied to central lines; CHG wipes were routinely used on the inpatient units beginning in January 2010. Colonized patients were placed into contact isolation, with decolonization at the primary team’s discretion.

MRSA carriage was defined by results of the first nasal swab collected between two weeks prior to transplant arrival date and transplant. Bacteremia was defined as isolation of MRSA from any blood culture. Pneumonia was defined as isolation of ≥103 colony forming units of MRSA from bronchoaveolar lavage (BAL) in conjunction with clinical/radiologic findings consistent with pneumonia. The incidence rates of bacteremia and pneumonia were assessed through 100 days post-transplant; 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated based on a Poisson distribution. Characteristics of patients with missed screens were assessed using Pearson’s chi-squared test. The study was approved by the center’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

A total of 1895 patients were transplanted between 1/1/2008 and 12/31/2012 and eligible for inclusion in the cohort; demographics are listed in Table 1. Nearly all patients, 1770/1895 (93.4%), were screened for MRSA at a median of 8 days after arrival to the center (interquartile range = 7 days). Patients not screened (125/1895 [6.6%]) were more likely to have undergone autologous transplant (p≤0.001) or an allogeneic transplant with multiple arrival visits (p=0.02).

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of adult hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, 2008–2012

| Variable | n (%) (n=1895) |

|---|---|

| Age (years)--median (IQR)* | 55.5 (44.3, 62.6) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1131 (59.7) |

| Female | 764 (40.3) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 1496 (84.3) |

| Black | 44 (2.5) |

| Hispanic | 50 (2.8) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 109 (6.1) |

| Native American | 16 (0.9) |

| Other | 59 (3.3) |

| Transplant Type | |

| Allogeneic related | 324 (17.1) |

| Allogeneic unrelated | 595 (31.4) |

| Autologous | 965 (50.9) |

| Syngeneic | 11 (0.6) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Acute leukemia† | 482 (25.4) |

| Multiple myeloma | 439 (23.2) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 207 (10.9) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 410 (21.6) |

| Other | 357 (18.8) |

IQR=interquartile range

Includes acute myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoid leukemia

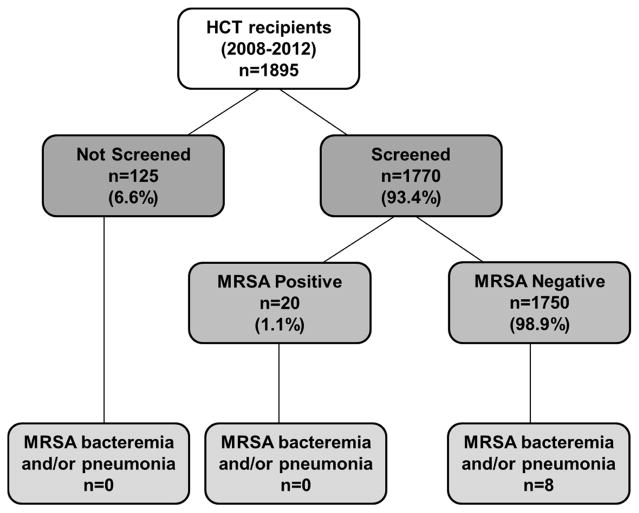

The prevalence of MRSA nasal carriage was low among screened patients (20/1770 [1.13%]). Six patients that screened positive were treated with intranasal mupirocin. Among all patients in the cohort, seven developed MRSA bacteremia and two developed MRSA pneumonia, with incidence rates of 0.39 (95% CI: 0.15, 0.80) and 0.11 per 10,000 patient-days (95% CI; 0.01, 0.40), respectively. Most bacteremia cases (6/7) occurred within two weeks post-transplant, where pneumonia developed later (day +16 and +95); there was no evidence of clustering of events. There were two MRSA-associated deaths, one 12 days after MRSA bacteremia and one 12 days after MRSA pneumonia diagnosis. All patients that developed MRSA bacteremia or pneumonia had negative pre-transplant nasal cultures for MRSA (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship between pre-transplant screening and post-transplant MRSA events in adult hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, 2008–2012

DISCUSSION

This retrospective study conducted at a large comprehensive cancer center demonstrated that the prevalence of pre-transplant MRSA nasal carriage detected by culture was low in HCT recipients. Furthermore, no patients with proven pre-transplant nasal carriage developed post-transplant MRSA complications. Together, these findings bring into question the value of pre-transplant MRSA screening by nasal culture in HCT patients.

The limited published data on pre-transplant MRSA carriage in HCT recipients are consistent with our findings. A single center study following a nosocomial outbreak reported that 15/776 (1.9%) HCT recipients were MRSA colonized at any point pre-transplant.3 Another, found no MRSA in 45 HCT recipients with pre-transplant nasal screening.7 Low rates of carriage are somewhat unexpected, as HCT recipients commonly have multiple risk factors for MRSA acquisition, including extensive contact with healthcare environments, frequent antibiotic exposure, and a history of invasive procedures.8

With the exception of a small case series,9 no studies have linked post-transplant MRSA complications to pre-transplant screening in HCT recipients. Although the low rates of MRSA complications in our population are consistent with other studies,4,7 the small number of events did not permit us to quantify the relationship between pre-transplant carriage and post-transplant MRSA complications. However, an association has been demonstrated in other populations,10 and may be detectable at centers with higher prevalence of MRSA or more sensitive screening methods.

Our study has limitations commonly seen in retrospective analyses. Data on antibiotic use and decolonization efforts prior to arrival at our center were unknown, and may have affected the results. Variance in timing, missed screens, the use of culture rather than PCR, and restricting screening to the nares, rather than expanded screening with additional sites, likely led us to underestimate the number of colonized patients. It is unknown whether our results are generalizable to other centers, particularly those with higher MRSA prevalence, as increased colonization pressure is an important risk factor for MRSA acquisition.11 Routine screening along with aggressive eradication efforts have been successful in preventing transmission during an outbreak of MRSA in HCT recipients,3 but it is unclear whether these benefits extend to non-outbreak settings. Despite these limitations, this study is the largest to date to provide both carriage prevalence and outcome data associated MRSA in HCT recipients.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that the burden of MRSA in this cohort of HCT recipients was minimal, and routine pre-transplant MRSA screening may have limited impact. These data are highly relevant to IP programs at hospitals that care for HCT recipients, and may help inform MRSA screening policies for these high-risk patients. However, further studies are needed to confirm our findings at other centers, as local MRSA epidemiology likely affects the value of pre-transplant screening in this population.

Acknowledgments

Support: S.A.P. is supported by NIH Grant K23HL096831.

Footnotes

Presentation of material in submitted manuscript: Data from this manuscript were presented in part at the Association of Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology 41st Annual Conference in Anaheim, CA, June 2014.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: S.A.P. has received research support and been a consultant for Merck, Sharp and Dohme, Corp. and Optimer/Cubist Pharmaceuticals. All other authors report no conflicts.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(10):1143–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garzoni C, Vergidis P. Methicillin-resistant, vancomycin-intermediate and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(Suppl 4 1):50–8. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw BE, Boswell T, Byrne JL, Yates C, Russell NH. Clinical impact of MRSA in a stem cell transplant unit: analysis before, during and after an MRSA outbreak. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39(10):623–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mihu CN, Schaub J, Kesh S, et al. Risk factors for late Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a single-institution, nested case-controlled study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(12):1429–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstock DM, Conlon M, Iovino C, et al. Colonization, bloodstream infection, and mortality caused by vancomycin-resistant enterococcus early after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(5):615–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green ML, Leisenring W, Stachel D, et al. Efficacy of a viral load-based, risk-adapted, preemptive treatment strategy for prevention of cytomegalovirus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(11):1687–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nusair A, Jourdan D, Medcalf S, et al. Infection control experience in a cooperative care center for transplant patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(5):424–9. doi: 10.1086/587188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucet J-C, Chevret S, Durand-Zaleski I, Chastang C, Régnier B. Prevalence and risk factors for carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at admission to the intensive care unit: results of a multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(2):181–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato N, Tanaka J, Mori a, et al. The risk of persistent carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol. 2003;82(5):310–2. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0626-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis Ka, Stewart JJ, Crouch HK, Florez CE, Hospenthal DR. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) nares colonization at hospital admission and its effect on subsequent MRSA infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(6):776–82. doi: 10.1086/422997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merrer J, Santoli F, Appéré de Vecchi C, Tran B, De Jonghe B, Outin H. “Colonization pressure” and risk of acquisition of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a medical intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21(11):718–23. doi: 10.1086/501721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]