Abstract

Objective:

The main objective of this study is to formulate polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) loaded with zaltoprofen, an NSAID drug. The optimization, in terms of polymer concentration, stabilizer concentration and pH of the formulation was employed by 3-factor-3-level Box-Behnken experimental design.

Materials and Methods:

The NPs of zaltoprofen were fabricated using chitosan and alginate as polymers by ionotropic gelation. The ionic interaction between the ionic polymers was studied using Fourier transform infrared and differential scanning calorimetry study.

Result:

For different formulation the average particle size ranged between 156 ± 1.0 nm and 554 ± 2.8 nm. The drug entrapment ranged between 61.40% ± 3.20% and 90.20% ± 2.47%. The ANOVA results exhibited that all the three factors were significant. The resultant optimized batch was characterized by particle size 156.04 ± 1.4 nm, %entrapment efficacy 88.67% ± 2.0%, zetapotential + 25.3 mV and polydispersity index 0.320. The scanning electron microscopy showed spherical NPs of average size 99.5 nm. The optimized NPs were loaded in carbopol gel, which was subjected to study of drug content, viscosity, spreadability, in vitro drug diffusion and in vivo antiinflammatory test on rats.

Conclusion:

This study showed that zaltoprofen NPs prepared using the ratio of polymer CS:AG:1:1.8, stabilizer concentration 0.98% and pH 4.73 was found to be of optimized particle size, maximum drug entrapment. The NPs loaded gel showed controlled release for 12 h following Korsmeryer-peppas model of the diffusion profile. The in vivo antiinflammatory study showed prolonged effect of NPs loaded gel for 10 h.

Keywords: Antiinflammatory study, Box-Behnken, chitosan nanoparticle, diffusion study, scanning electron microscopy

INTRODUCTION

Zaltoprofen (2-(10-oxo-10, 11, dihydrodibenzo [b, f] thiepin-2-yl) propionic acid belongs to the class of NSAIDs.[1] It is a low molecular weight drug that acts by inhibiting the bradykinin-induced responses by blocking bradykinin interaction with the bradykinin β2 receptor on dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons.[2] Zaltoprofen also significantly inhibits bradykinin-induced 12-lipoxygenae activity and the slow bradykinin-induced onset of substance P from DRG neurons. All these results suggest that zaltoprofen possesses novel antiinflammatory mechanism, which inhibits β2-type BK receptor function in nerve endings.[3]

Zaltoprofen is marketed in as a tablet of dosage regimen of 80 mg thrice a day for adults. Further, the attempt is also attempt is made to reduce the side effect and increase the bioavailability by exempting the first pass effect on the drug. Zaltoprofen is a short half-life drug, so a need arises for a sustained release formulation, which is beneficial to increase the patient compliance.[3]

Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) have attracted prominent interest in past few decades as a novel drug carrier due to its longer half-life and greater drug entrapment efficacy.[4,5] The polymeric NPs embraced the site-specific targeting and tend to permeate deeply into the skin substructures that are attributed to its nanoscale particle size.[6] Moreover, the biodegradable NPs can protect the drug from the harsh environment and prolong the duration of drug mucoadhesion at target tissues.[7,8] Antiinflammatory drugs represent a broad range of molecules, many with potential for topical delivery.[9] The reports on NP delivered drug with antiinflammatory properties for topical use include: Aceclofenac, betamethasone-17-valerate, celecoxib, flufenamic acid, flurbiprofen, ketoprofen and naproxen.[10,11]

In this research, the attempt is made to formulate a zaltoprofen drug loaded Chitosan-Alginate nanoparticles (NPs).[12,13] The pH of the formulation, polymer ratio, stabilizer concentration and stirring speed, as well as stirring time, is adjusted to yield drug loaded NPs. Thus, biode gradable NP is designed to increase drug loading, increase the penetration into skin tissues due to its nanosize, and show controlled release of drug from polyelectrolyte complex.[14] The NPs are further incorporated into gel and form topical delivery at site of action for inflammation disease. Thus, the side-effects of its marketed tablet are eliminated as topical delivery reduces first pass effect as well as protect from gastric mucosa irritation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Sodium dihydrogen phosphate dehydrate (S.D. Fine Chem Ltd.), Sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, acetic acid, carbopol 934, propylene glycol, triethanolamine (Finar Reagent), Chitosan and Alginate were bought from S.D. Fine Chem Ltd., Mumbai. The API Zaltoprofen and the surfactant Poloxamer F127 was obtained as gift sample from Lincoln Pharmaceuticals, Mehsana.

Methods for formulation

Methodology for preparing of CS-AG nanoparticles

The CS-AG NPs were prepared by modified coacervation method known as ionotropic gelation.[15] Prior to this the polymer solutions were prepared by dissolving chitosan in 1% v/v acetic acid and alginate in deionized water. The pH (4.6-5.0) was adjusted with the help of 0.1M NaOH/0.1M HCl. Briefly, the aqueous solution of alginate was added drop-wise into the chitosan solution containing Pluronic F-127 under continuous magnetic stirring at 1000 rpm for 30 min. For the preparation of drug loaded NP, zaltoprofen in methanol was mixed with chitosan solution prior to addition of alginate solution. NPs were formed as a result of the interaction between the negatively charged carboxylic groups of AG and the positively charged amino groups of CS (ionotropic gelation). NPs were collected by ultracentrifugation (REMI high speed, cooling centrifuge, REMI Corporation, India) at 18,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C.

Statistical modeling

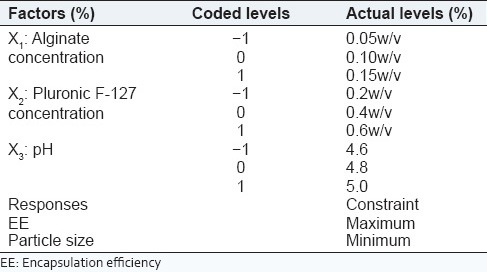

In this experiment, Box-Behnken design was adopted for the optimization process such as finding the optimal conditions for targeted results.[16,17] The three levels selected for three factors were based on trial experiments. Their levels are summarized in Table 1. All analytical treatments were performed using Design-Expert 8.0 software, Manufactured by Stat-Ease, Inc. Analysis of variance was carried out to determine the significance of the fitted equation.[15] The process variables, their coded experimental values, are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Process variables and responses with constraints for Box-Behnken factorial design

Table 2.

Matrix of Box-Behnken design

Freeze-drying of nanoparticles

The obtained NPs after ultracentrifugation was redispersed into de-ionized water. Mannitol (5%) was added as a cryoprotectant to samples and frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized (VirTris BenchStop lyophilizer) for 24 h at condenser temperature of −99°C and 50 mT vaccum pressure.

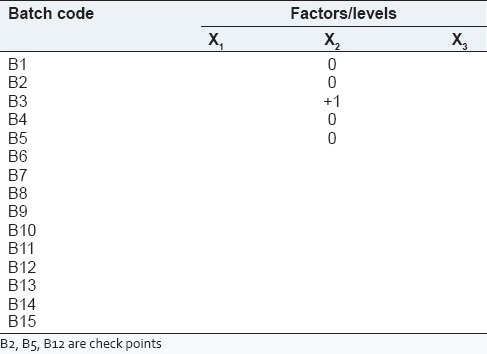

Drug loading

The drug loading in optimized formulation result in different four batches namely F1 (10 mg), F2 (20 mg), F3 (30 mg) and F4 (40 mg). The loading capacity of zaltoprofen in CS-AG NPs was calculated as,[18]

Formulation of topical gel containing zaltoprofen loaded CS-AG nanoparticles

The F1, F2, F3 and F4 batches were incorporated into 1% (w/w) carbopol gel with an electrical mixer (25 rpm, 2 min).[19] This resulted in NPs loaded gels labeled as G1 gel (0.8% w/w), G2 gel (1.6% w/w), G3 gel (2.8% w/w), G4 (3.7% w/w). Similarly, plain drug gel of 2% zaltoprofen was labeled as P1 gel.

Characterization of NPs

Morphology and size determination

The freeze-dried samples of zaltoprofen loaded CS-AG NPs were mounted on metal stubs plating coated under vaccum and then examined on JSM-5610 scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at ×550, ×1000, ×2700 and ×20,000 magnification. NP size and zeta potential were assessed by dynamic lights cattering (DLS) using a DTS version 5.10, serial Number: MAL1025328, Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern zeta-sizer. All DLS measurements were done with a wavelength of 532nm at 25°C with anangle of detection 90°. All measurements were performed in triplicate, and standard deviation was recorded.

Fourier transform analysis (Fourier transformin frared) study

Samples were lyophilized, mixed with micronized KBr powder and compressed into discs using a normal tablet press. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) Spectra were obtained using 8400S FTIR-Spectrophotometer.

Differential scanning calorimetry study

Differential scanning calorimetric analysis was used to characterize the thermal behavior using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC-60) (ShimadzuCo., Japan.). 2.0 mg of dried powder of formulation crimped in a standard aluminum pan and heated from 20°C to 350°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min under constant purging of nitrogen.

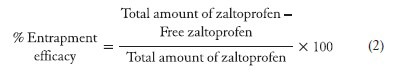

%Entrapment efficacy

To determine encapsulation efficiency (%EE) of NPs, they were first separated by ultracentrifugation at 18,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C from the aqueous medium containing nonassociated zaltoprofen. The supernatant was collected and quantified spectrophotometerically at λmax 243.40 nm of drug.[20] The amount of zaltoprofen loaded into NPs was calculated as the difference between the total amount used to prepare loaded NP and that recovered as nonassociated drug. The drug %EE of the NPs was calculated by the following equation:

Characterization of gel

Appearance of gel

All developed gels were tested for homogeneity by visual inspection after the gels have been set in the container. They were tested for their appearance and presence of any aggregates.

pH and viscosity of the gel

The pH values of 1% aqueous solutions of the prepared gels were measured by a pH meter (Welltronix Digital pH meter PM 100). Viscosity of prepared gels was measured by Brookfield-DV-II+Pro Viscometer. Apparent viscosity measured at 25°C and rotating the spindle S95 at 20 rpm with maximum torque.

Drug content of the gel

A specific quantity (100 mg) of developed gels were taken and dissolved in 100 ml of phosphate buffer. The volumetric flask containing gel solution was shaken for 2 h on the mechanical shaker in order to get complete solubility of the drug. This solution was filtered and estimated spectrophotometerically at 243.40 nm using phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) as blank.[20]

Spreadability study of gel

An excess of gel (about 2 g) under study was placed on the ground slide. The gel was then sandwiched between this slide and another glass slide having the dimension of fixed ground slide and provided with a hook. A 1 kg weight was placed at the top of the two slides for 5 min to expel air and to provide a uniform film of the gel between the slides. Excess of the gel was scrapped off from the edges. The top plate was then subjected to pull of 80 g with the help of string attached to the hook and the time (in seconds) required by the top slide to cover a distance of 7.5 cm was noted. A shorter interval indicated better spreadability.[19] Spreadability was calculated using the following formula:

M = Weight tied to the upper slide

L = Length moved by the glass slide

T = Time (in sec) taken to separate the upper slide from the ground slide.

In vitro drug diffusion study

In vitro diffusion studies were carried out to compare the release behavior of drug from carbopol gel and NPs loaded in carbopol gels (G1), (G2), (G3) and (G4), by dialysis method using cellophane membrane as a semi permeable membrane. The gel formulation was taken in an open ended tube tied with cellophane membrane and placed into a receptor compartment containing distilled phosphate buffer pH 6.8 stirred by magnetic stirrer (Franz diffusion cell). The contents were uniformly rotated by a magnetic bead at 50 rpm at 37°C ± 2°C. The samples were taken periodically, and the absorbance was measured at 243.40 nm by ultraviolet (UV)-spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800).[21] The cumulative percentage drug release was plotted against time to compare the release pattern from all gel formulations.

Drug diffusion kinetic study

The in vitro release pattern was evaluated to check the goodness of fit to the zero-order release kinetics equation 4, first order kinetics equation 5, Higuchi's square root of the time equation 6 and Korsmeyer's Peppas power law equation 7:

-

Zero order releases

- f (t) = K0 × t (release proportional to amount of drug remaining) (4)

-

First order release

- lnQt = lnQ0 + K × t (release independent of drug concentration) (5)

-

Higuchi's square root of the time equation

- f (t) = KH × t½ (release proportional to square root of time) (6)

-

Korsmeyer-Peppas’ power law equation

- Mt/M∞ = K × tn (7)

The goodness of fit was evaluated using ‘r’ (correlation coefficient) values.

Antiinflammatory activity of the gel on carrageenan induced paw edema model

Experimental animals

Albino Wistar rats of either sex, weighing 150-200 g were used. They were housed in standard environmental conditions and fed with standard rodent diet with water ad libitum. All animal procedures were followed in three groups namely Control, Test and Standard of six animals each.[22]

Carrageenan induced rat paw-edema

Animals were fasted for 24 h before the experiment with water ad libitum. Approximately 50 μl of a 1% suspension of carrageenan in saline was prepared 1 h before each experiment and was injected into the plantar side of right hind paw of the rat. Maximum inflammation was observed after 2 h of injection. 1 g G3 gel was applied to the plantar surface of the hind paw by gentle rubbing 50 times with the index finger. Rats of the control groups received the carbopol gel without drug and 1 g P1 gel was used as a standard. Paw volume was measured immediately after carrageenan injection and at 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 h intervals after the administration of the noxious agent by using a plethysmometer[21,22]

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

Optimization of formulation using Box-Behnken surface response

The results obtained for 15 formulations are shown in Table 3. The average particle size ranged between 156 ± 1.0 nm and 554 ± 2.8 nm. The drug entrapment ranged between 61.40% ± 3.20% and 90.20% ± 2.47%.

Table 3.

Results of measured responses

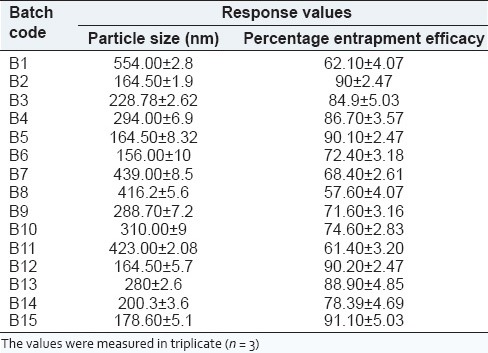

Regression analysis

The optimization resulted in achieving 88.67% entrapment efficacy and 156.04 nm particle size. For predicting the optimal region, a second-order polynomial function was fitted to correlate the relationship between variables and responses.[17] The behavior of the system was explained using following quadratic equation:

Y = β0 + Σ βi Xi + Σβij Xi Xj + Σβii Xi2 (8)

Where, Y is predicted the response, β0 is a model constant (intercept), βi is linear offset, βii is squared offset and βij is the interaction effect. Xi and Xj are dimensionless coded value of independent variables. The quality of fit of polynomial model equation was expressed by adjusted coefficient of determination R2adj.[23] The values were found to be 0.95 and 0.98 for % entrapment efficacy and particle size respectively.

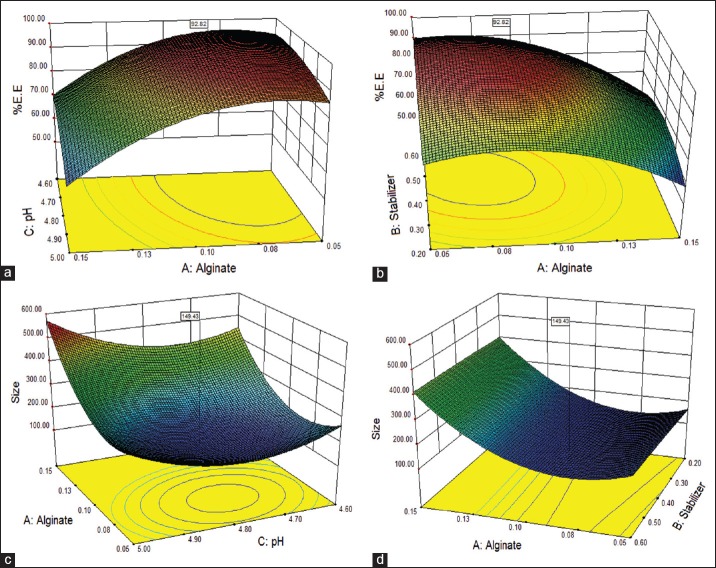

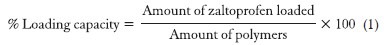

Response-surface analysis

The aim of optimization is to find the optimization levels of the variables that affect the process, whereby a product of desired characteristics can be produced easily and reproducibly.[23] Using the response-surface of selected responses with constraint (maximum entrapment efficacy and minimum particle size); it was possible to identify the optimum region. Figure 1 shows three-dimensional relationship between factors and responses.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional surface plots of entrapment efficacy and particle size as a function of alginate concentration, stabilizer concentration and pH: (a) Insignificant changes in encapsulation efficacy due to change in pH. This may be due to fact that increases in pH from optimal level leads to lesser ionic interaction between chitosan and alginate to form nanoparticles (NPs). (b) Moreover shows that there is a proportional relationship between stabilizer and %entrapment efficacy. (c) That pH around intermediate level allows stronger interaction between CS-AG leading to more compact and smaller NPs. (d) Depicts that there is no effect of stabilizer on particle size

Effect of factors on response

% Entrapment efficacy

ANOVA results and regression coefficient are shown in Table 4. All three variables were statistically significant (P < 0.05) and exhibited positive influence on the responses. From the surface plots of responses for % entrapment efficacy, it can be concluded that alginate concentration was factor with the greatest influence and had a positive effect (i.e., response increases with an increase in factor level).

Table 4.

ANOVA results (P values): Effect of the variables on % entrapment efficacy and particle size

Particle size

As shown in Table 4, the pH (factor X3, most influential) had a positive coefficient, while the alginate concentration had a negative coefficient. All three process variables were statically significant (P < 0.05). The particle size is also influenced by the orifice of the needle through which solution is allowed to pass, addition of surfactant, rate of addition, stirring speed and time.

Moreover, the increased viscosity at higher concentration of polymer resulted in larger size particle. The desired size was optimized at intermediate level of pH variable. The surfactant concentration showed a positive response for lower size constraint. The surfactant acts as a stabilizer as well as solubilizer of zaltoprofen for the formulation.

Interaction between factors

The ANOVA results [Table 4] showed that the interaction X1 × 2 had a significant influence on the percent entrapment as well as on particle size. However, this interaction was found to have a positive influence for particle size and negative influence on % entrapment efficacy. However, interaction terms X1×3 and X2×3 were nonsignificant statistically for both responses.

Evaluation of zaltoprofen loaded CS-AG nanoparticles

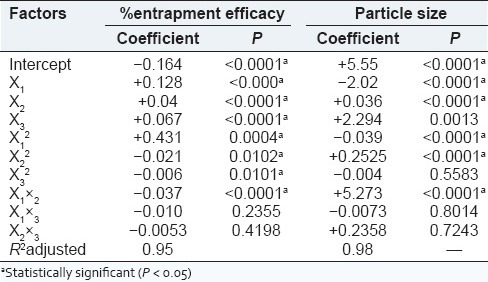

Morphology and size determination

The SEM study of freeze-dried formulation showed distinct, spherical, and spongy dense structure with diameter to be 99 nm [Figure 2]. The NPs appeared to be considerably smaller when viewed with SEM as compared to average particle size observed with DLS. This apparent disperancy between the two results can be explained by dehydradation of CS-AG NPs during lyophilization. The DLS measures the apparent size (hydrodynamic radius) of a particle, including hydrodynamic layers that form around hydrophilic particles such as those composed of CS-AG, leading to overestimation of NPs size.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy micrographs of optimized zaltoprofen loaded chitosan-alginate nanoparticles at (a) ×550, (b) ×1000 and (c) ×20,000

Fourier transform infrared

The FTIR spectrum of chitosan showed strong protonated amino peak at 1596 cm−1. Consequently, after complexation with Chitosan-alginate, carboxyl peaks of alginate near 1631 cm−1 and 1425 cm−1 were broadened and shift slightly from this values to 1567 cm−1–1411 cm−1 and the amino peak disappeared. The amide peak at 1534 cm−1 was observed.

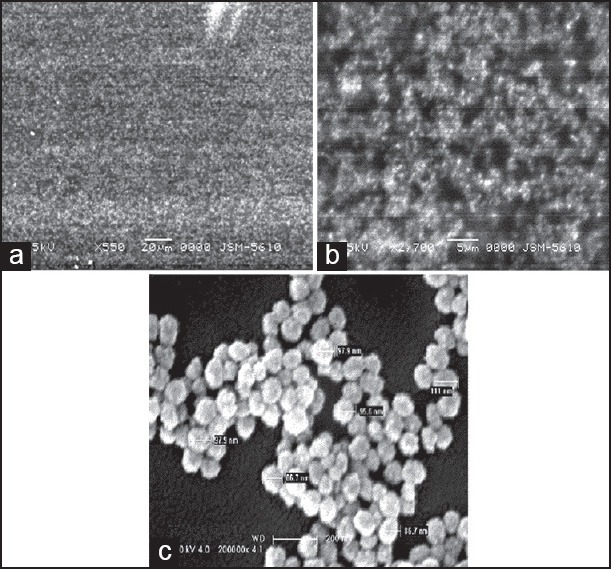

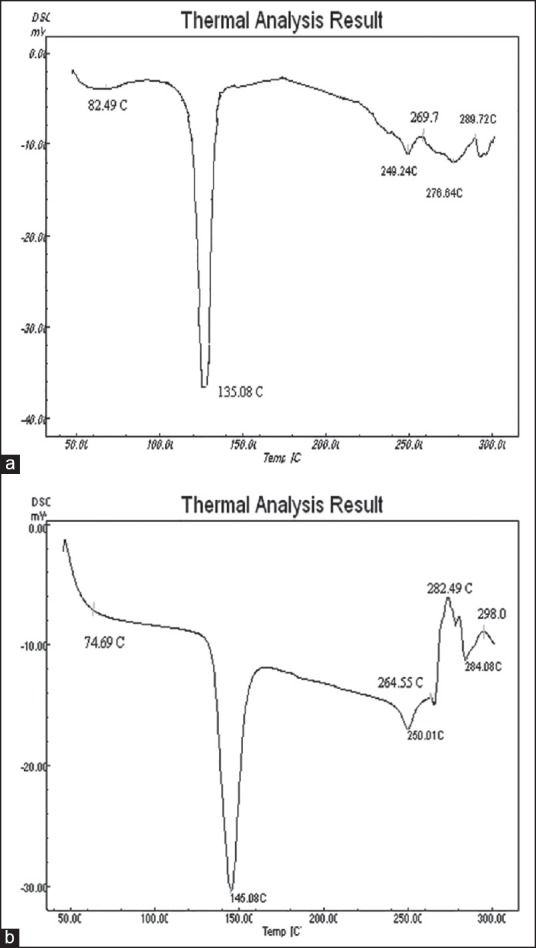

Differential scanning calorimetry

It could be seen from Figure 3 that the peaks of the drug loaded NPs were shifted from those of physical mixtures of polymers and zaltoprofen. The formulation showed the forward shifts for chitosan from 82.49°C to 74.69°C. The peak was endothermic and broader than that observed in individual polymers. The characteristic peak of zaltoprofen (M.P. 137.4°C) was also detected at 145.08°C in the thermogram of NPs. The melting point was increased to 7.6°C after getting encapsulated to the polyelectrolyte complex. The peaks of physical mixture of polymers and drug appeared to be a combination of each material, but they were different from those obtained for NPs loaded zaltoprofen probably because of complexation of polyelectrolytes resulted in new chemical bond, amide.

Figure 3.

Thermograms of (a) physical mixture of polymers and zaltoprofen and (b) zaltoprofen loaded CS-ALG nanoparticles formulation

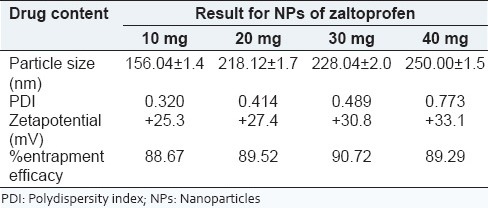

%loading capacity

The optimized batch was considered for increasing drug payload. The results show that CS-AG NPs can entrap up to 30 mg of zaltoprofen effectively. The characteristic evaluation of zaltoprofen loaded CS-AG NPs with increasing amount of drug is shown in Table 5. It is observed that increase in the amount of drug content comparatively increases the particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), zeta-potential as well as % entrapment efficacy.

Table 5.

Characteristic evaluation of NPs of zaltoprofen

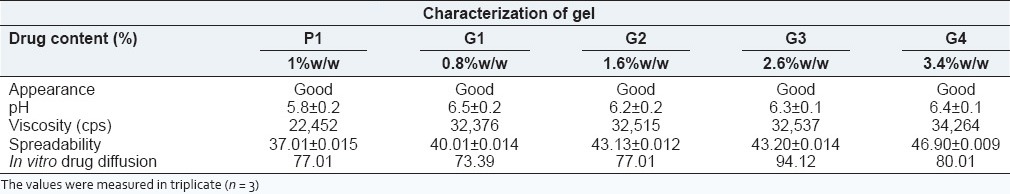

Evaluation of gel

The plain drug gel was comparatively transparent than gel containing NPs of drug. The pH and viscosity value of the gel with nanoformulations was higher than that of plain drug gel. The comparative results for characteristics of gels are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Characteristic evaluation of gels

In vitro diffusion study

The zaltoprofen release from carbopol gel P1 shows an uncontrolled, erratic and uneven release pattern. The G1 and G2 gels exhibit 73.39% and 77.01% cumulative drug release at end of 12 h respectively. Thus, it was observed from results in Table 6 that as drug loading increases the cumulative release also improves relatively. The maximum cumulative drug release from NPs was found for G3 gel. The similarity factor was 45 suggesting dissimilarity between their release patterns. The hydrophobic drug was entrapped into hydrophilic polymer shows a prolonged release, but in a time-controlled manner, which is improves the release profile of zaltoprofen.

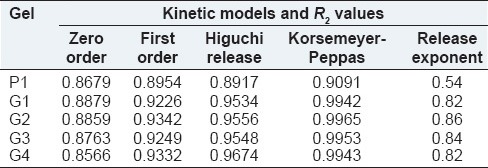

Drug diffusion kinetic study

The values of R2 for different mathematical models are shown in Table 7. The R2 values (~0.99) for zaltoprofen loaded carbopol gel and NPs loaded gels depicts that Korsemeyer-Peppas model fits best. The drug release from plain drug gel (P1) shows sustained release with critical ‘n’ value 0.54. The drug release from CS-AG NP also followed Korsmeyer-Peppas model with the critical value of “n” being between 0.82 and 0.86 suggesting non-Fickian diffusion processes. A sequential process of polymer hydration, solvent penetration, and drug dissolution and/or polymer erosion determine the drug release from hydrophilic matrixes.[24]

Table 7.

Kinetic modeling of diffusion profile from gels

Antiinflammatory activity of gels

The increase in %inhibition in paw-edema was seen up to 6 h and 10 h for P1 and G3 gels respectively. Thus G3 gel had a prolonged action than P1 gel. The highest % inhibition of paw-edema for G3 gel reached upto 50% at end of 10 h due to controlled release of zaltoprofen from CS-AG NP matrixes.

CONCLUSION

The objective of present investigation was to explore potential of CS-AG NPs as drug carrier system. Zaltoprofen, an NSAID drug, was entrapped in CS-AG NPs using ionotropic gelation method. The formulation was statistically optimized by experimental design considering the concentrations of polymer, stabilizer and pH of the system as independent variables. The ionic interaction between amino group of chitosan and carboxylic group of alginate was confirmed by FTIR and DSC studies.

These zaltoprofen loaded NPs were characterized by particle size, morphology, zetapotential, PDI and % entrapment efficacy. The optimized condition was obtained using Box–Behnken. The resultant NPs were dense, spherical NP with particle size of 156.04 ± 1.4 nm and entrapment efficacy of 88.67 ± 2.0%. The +25.3 mV zetapotential of system indicated good stability of NPs and 0.320 PDI indicated aggregation free system. Further the drug loading in the optimized batch concluded that increase in drug payload increases % entrapment efficacy. In vitro diffusion studies showed that the drug undergoes sustained diffusion from the optimized formulation over period of 10 h, primarily by non-Fickian diffusion. Thus it is concluded that CS-AG NPs improves the uneven and erratic drug release profile of zaltoprofen. In in vivo studies the NPs loaded gel showed anti-inflammatory activity for prolonged period while the gel with plain zaltoprofen showed abrupt decrease inactivity. Thus formulation helps in improving efficacy of drug.

This new formulation is a viable alternative to conventional tablet by virtue of its ability to sustain the drug release, for its ease of administration because of topical gel which aids in better patient compliance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The work is financially supported by Shree S.K. Patel College of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Ganpat University. Kherva - 384 012, Mehsana. Gujarat.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Financial support from Shree S K Patel College of Pharmaceutical Edu and Res.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Secretariat JP Japanese Pharmacopeia Committee. Japan Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. 15th ed. Japan: Society of Japanese Pharmacopeia; 2006. Japanese Pharmacopeia XV; pp. 1242–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirate K, Uchida A, Ogawa Y, Arai T, Yoda K. Zaltoprofen, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, inhibits bradykinin-induced pain responses without blocking bradykinin receptors. Neurosci Res. 2006;54:288–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang HB, Inoue A, Oshita K, Hirate K, Nakata Y. Zaltoprofen inhibits bradykinin-induced responses by blocking the activation of second messenger signaling cascades in rat dorsal root ganglion cells. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:1035–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soppimath KS, Aminabhavi TM, Kulkarni AR, Rudzinski WE. Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles as drug delivery devices. J Control Release. 2001;70:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Y, Yang W, Wang C, Hu J, Fu S. Chitosan nanoparticles as a novel delivery system for ammonium glycyrrhizinate. Int J Pharm. 2005;295:235–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davda J, Labhasetwar V. Characterization of nanoparticle uptake by endothelial cells. Int J Pharm. 2002;233:51–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00923-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehr CM, Bouwstra J, Schacht E, Junginger H. In-vitro evaluation of mucoadhesive properties of chitosan and some other natural polymer. Int J Pharm. 1992;78:43–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinaudo M. Chitin and Chitosan: Properties and applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2006;31:603–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janes KA, Calvo P, Alonso MJ. Polysaccharide colloidal particles as delivery systems for macromolecules. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;23(47):83–97. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prow TW, Grice JE, Lin LL, Faye R, Butler M, Becker W, et al. Nanoparticles and microparticles for skin drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63:470–91. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danielsen S, Maurstad G, Stokke BT. DNA-polycation complexation and polyplex stability in the presence of competing polyanions. Biopolymers. 2005;77:86–97. doi: 10.1002/bip.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hejazi R, Amiji M. Chitosan-based gastrointestinal delivery systems. J Control Release. 2003;89:151–65. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly M, Knoor D. Chitosan-alginate complex coacervates capsules – Effects of calcium chloride, plasticizer and polyelectrolyte on mechanical stability. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;4:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu X, Gao H, Li C, Yang YW, Wang Y, Fan Y, et al. Polyelectrolyte complex nanoparticles of amino poly(glycerolmethacrylate) s and insulin. Int J Pharm. 2012;423:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvo P, Alonso MJ. Evaluation of cationic polymer-coated nanocapsules as ocular drug carriers. Int J Pharm. 1997;53:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plackett RL, Burman JP. The design of optimum multifactorial experiments. Brometrika. 1946;33:305–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunter JS. G.E.P. Box. Multifactorial design for exploring response surfaces. Ann Math Stat. 1957;28:195–241. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pawinee N, Wantanee R, Assadang P, Norang S. Development of acylovir-loaded bovine serum albumin nanoparticles for ocular drug delivery. Int J Drug Deliv. 2011;3:669–75. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel R, Patel H, Baria A. Formulation and evaluation of carbopolgel containing liposomes of ketoconazole. Int J Appl Pharm. 2011;3:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aher KB, Bhavar GB, Joshi HP, Chaudhari SR. Economical spectrophotometric method for estimation of zaltoprofen in pharmaceutical formulations. Pharm Methods. 2011;2:152–6. doi: 10.4103/2229-4708.84443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogel HG. 3rd ed. New York: Springer Publication; 2008. Drug Discovery and Evaluation: Pharmacological Assay; p. 1315. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marwaha M, Marwaha R, Padi S, Madaan I, Rishipal A. Pharmacodynamic investigation of gels containing a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug on experimental inflammation and related hyperalgesia. Int J Compr Pharm. 2010;2:45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Candioti LV, Robles JC, Mantovani VE, Goicoechea HC. Multiple response optimization applied to the development of a capillary electrophoretic method for pharmaceutical analysis. Talanta. 2006;69:140–7. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sankalia MG, Mashru RC, Sankalia JM, Sutariya VB. Reversed chitosan-alginate polyelectrolyte complex for stability improvement of alpha-amylase: Optimization and physicochemical characterization. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;65:215–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]