Abstract

Copper-64 (t1/2 = 12.7 h, β+: 17.4%, Eβ+max = 656 keV; β−: 39%, Eβ-max = 573 keV) has emerged as an important non-standard positron-emitting radionuclide for PET imaging of diseased tissues. A significant challenge of working with copper radionuclides is that they must be delivered to the living system as a stable complex that is attached to a biological targeting molecule for effective imaging and therapy. Significant research has been devoted to the development of ligands that can stably chelate 64Cu, in particular, the cross-bridged macrocyclic chelators. This review describes the coordination chemistry and biological behavior of 64Cu-labeled cross-bridged complexes.

Introduction

Non-traditional positron-emitting radionuclides, particularly those of the transition metals, have gained considerable interest for imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) because of increased production and availability. Significant research effort has been devoted to the copper radionuclides because they offer a varying range of half-lives and positron energies as depicted in Table 1[1]. In addition, the well-established coordination chemistry of copper allows for its reaction with a wide variety of chelator systems that can potentially be linked to antibodies, proteins, peptides and other biologically relevant small molecules.

Table 1.

Decay Characteristics of Copper Radionuclides

| Isotope | t1/2 | β− MeV (%) | β+ MeV (%) | EC (%) | γ MeV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60Cu | 23.4 min | --- | 2.00 (69%) 3.00 (18%) 3.92 (6%) |

7.0% | 0.511 (186%) 0.85 (15%) 1.33 (80%) 1.76 (52%) 2.13 (6%) |

| 61Cu | 3.32 h | --- | 1.22 (60%) | 40% | 0.284 (12%) 0.38 (3%) 0.511 (120%) |

| 62Cu | 9.76 min | --- | 2.91 (97%) | 2% | 0.511 (194%) |

| 64Cu | 12.7 h | 0.573 (38.4%) | 0.655 (17.8%) | 43.8% | 0.511 (35.6%) 1.35 (0.6%) |

| 67Cu | 62.0 h | 0.395 (45%) 0.484 (35%) 0.577 (20%) |

--- | --- | 0.184 (40%) |

Coordination Chemistry of Copper

The aqueous solution coordination chemistry of copper is limited to its three accessible oxidation states (I-III) [2-4]. The lowest oxidation state, Cu(I) has a diamagnetic d10 configuration and forms complexes without any crystal-field stabilization energy. Complexes of this type are readily prepared using relatively soft polarizable ligands like thioethers, phosphines, nitriles, isonitriles, iodide, cyanide and thiolates; however, Cu(I) complexes are typically not used for in vivo imaging due to their lability. Copper (II) is a d9 metal of borderline softness which favors amines, imines, and bidentate ligands like bipyridine to form square planar, distorted square planar, trigonal pyramidal, square pyramidal, as well as distorted octahedral geometries. Jahn-Teller distortions in six-coordinate Cu(II) complexes are often observed as an axial elongation or a tetragonal compression. Due to the presence of some crystal-field stabilization energy, Cu(II) is generally less labile toward ligand exchange and is the best candidate for incorporation into radiopharmaceuticals. A third oxidation state Cu(III) is relatively rare and difficult to attain without the use of strong π-donating ligands.

Production of 64Cu

Copper-64 can be effectively produced by both reactor-based and accelerator-based methods. One method of 64Cu production is the 64Zn(n,p)64Cu reaction in a nuclear reactor [5]. Most reactor-produced radionuclides are produced using thermal neutron reactions, or (n,γ) reactions, where the thermal neutron is of relatively low energy, and the target material is of the same element as the product radionuclide. For producing high-specific activity 64Cu, fast neutrons are used to bombard the target in a (n,p) reaction. This method enabled the production of high specific activity 64Cu at the Missouri University Research Reactor (MURR) in amounts averaging 250 mCi [5].

The production of no-carrier-added 64Cu via the 64Ni(p,n)64Cu reaction on a biomedical cyclotron was proposed by Szelecsenyi et al. In this study small irradiations were performed demonstrating the feasibility of 64Cu production by this method [6]. Subsequent studies by McCarthy et al. were performed, and this method is now used to provide 64Cu to researchers throughout the United States [7]. Recently, Obata et al. reported the production of 64Cu on a 12 MeV cyclotron, which is more representative of the modern cyclotrons currently in operation [8]. They utilized very similar methods to those previously published [7]. A remote system was described for separation of the 64Cu from the 64Ni target.

Chelating Ligands for 64Cu

Utilizing 64Cu of high specific activity with a chelator that forms a stable complex in vivo is critical in achieving high uptake of the copper radionuclide in the tissue or organ of interest while minimizing the non-selective binding or incorporation into non-target organs or tissues. Ligands that can form radio-copper complexes with high kinetic inertness to Cu(II) decomplexation (proton-assisted as well as transchelation or transmetallation) are ideal, since this is more significant than thermodynamic stability after the radio-copper complex is injected into a living organism [9, 10]. Reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I) and subsequent Cu(I) loss may also be a pathway for loss of radio-copper, and resistance of the radio-copper complex to Cu(II)/Cu(I) reduction as well as reversibility can also be important [11]. Rapid complexation kinetics are also essential to allow for the facile formation of the radio-copper complex. Finally, chelators also must be designed with available functional groups that allow them to be covalently linked to targeting peptides, proteins, and antibodies.

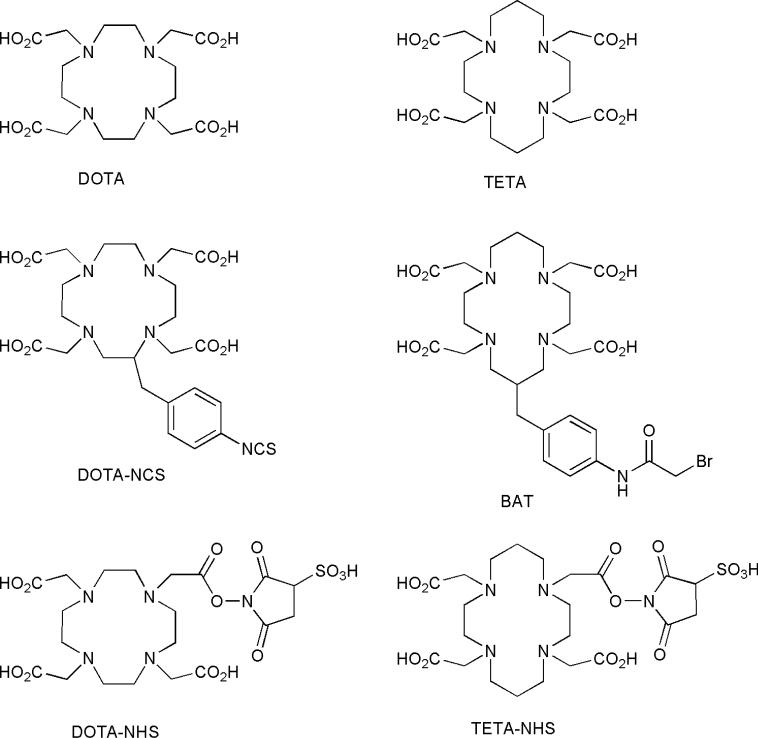

Chelators Based on Cyclam and Cyclen Backbones

The most widely used chelators for attaching 64Cu to biological molecules are tetraazamacrocyclic ligands with pendant arms that utilize both the macrocyclic and chelate effects to enhance stability. By far the most extensively used class of chelators for 64Cu has been the macrocyclic polyaminocarboxylates shown in Fig. (1). These systems have been thoroughly investigated, and in vitro and in vivo testing have shown them to be superior to acyclic chelating agents for 64Cu [12]. This enhanced stability is most likely due to the greater geometrical constraint incorporated into the macrocyclic ligand that enhances the kinetic inertness and thermodynamic stability of their 64Cu complexes [13-15]. Two of the most important chelators studied were DOTA (1) and TETA (2). While DOTA has been used as a BFC for 64Cu, its ability to bind many different metal ions, and its decreased stability compared to TETA make it less than ideal [16-21]. The tetraazamacrocyclic ligand TETA therefore, has been extensively used as a chelator for 64Cu, and successful derivatization of this ligand has allowed researchers to conjugate it to antibodies, proteins, and peptides [22-32].

Figure 1.

Cyclic polyaminocarboxylates and their derivatives.

Although 64Cu-TETA complexes are more stable than 64Cu-DOTA and 64Cu-labeled complexes of acyclic ligands, their instability in vivo has been well documented. Bass et al. demonstrated that when 64Cu-TETA-octreotide was injected into normal Sprague-Dawley rats, nearly 70% of the 64Cu from 64Cu-TETA-octreotide was transchelated to a 35 kDa species believed to be superoxide dismutase (SOD) in the liver 20 h post-injection [33]. These results are supported by the observations of Boswell et al. [34].

Despite the considerable efforts made by researchers to use tetraaza-tetracarboxylate macrocyclic ligands as effective BFCs for 64Cu, it is evident that the in vivo instability of these 64Cu complexes emphasizes the need for more inert 64Cu chelators. With this in mind, new ligand systems, including those based upon the cross-bridged (CB) tetraazamacrocycles have been developed to complex 64Cu more stably.

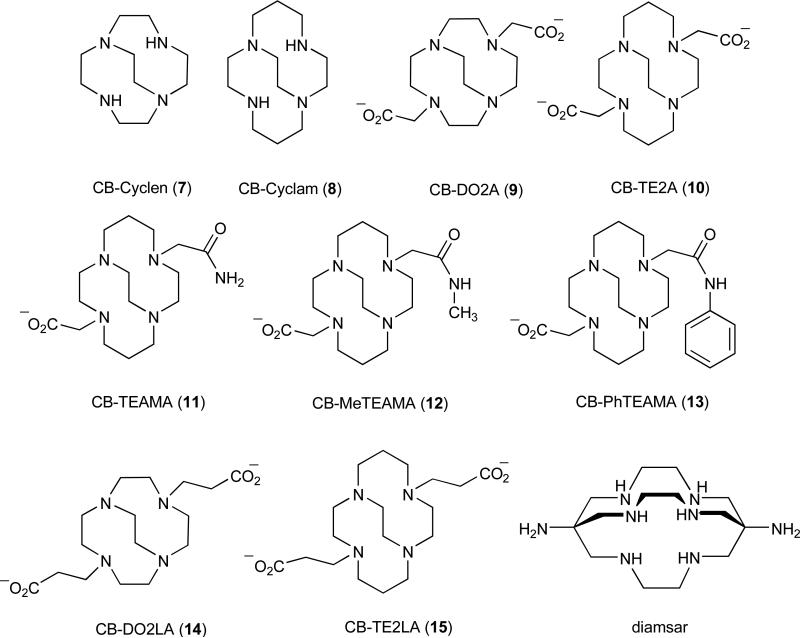

The Cross-bridged Tetraamine Ligands (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Cross-bridged macrocyclic complexes and analogs compared to the sarcophogene chelator, diamsar.

This class of chelators was first conceived of and synthesized by Weisman and Wong and coworkers in the 1990's [35, 36], and they were originally designed to complex metal cations like Li+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ within their clamshell-like clefts. Numerous copper complexes of these and related ligands have since been prepared and studied by Wong, Weisman and coworkers as well as other research groups [37-42]. With available structural data, the expected cis-folded coordination geometry of these chelators has been confirmed in all cases. Attachment of two carboxymethyl pendant arms to CB-cyclam (8) to give CB-TE2A (10) further ensures complete envelopment of a six-coordinate Cu(II) as shown in Fig. (3).

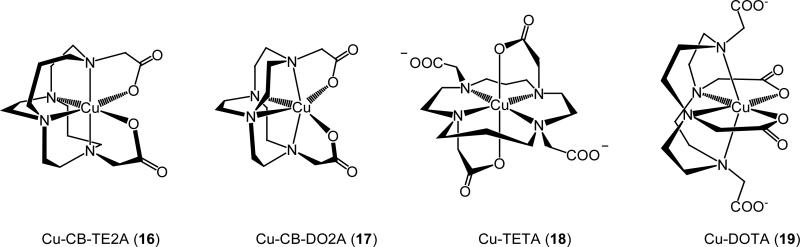

Figure 3.

A comparison of the structures of Cu(II) complexes of the CB ligands CB-TE2A and CB-DO2A with those of TETA and DOTA based on published crystallographic data from references [14, 15, 34, 42].

While the measurement of stability constants of Cu-CB complexes have been limited by the proton-sponge nature of these chelators, available data for Cu-CB-cyclam (log Kf = 27.1) revealed very similar values to non-bridged Cu-cyclam (log Kf = 27.2) and related complexes [43]. On the other hand, their kinetic inertness, especially in aqueous solution, has been shown to be truly exceptional [11, 44]. Proton-assisted decomplexation is a convenient indicator of solution inertness. Under pseudo-first order conditions of high acid concentration (e.g. 5 M HCl), decomplexation half-lives can provide a comparative gauge. Remarkable resistance of Cu-CB complexes toward such processes has recently been demonstrated [11, 44]. As shown in Table 2, Cu-CB-cyclam is almost an order of magnitude more inert than Cu-cyclam in 5 M HCl at 90°C, while Cu-CB-TE2A is 4 orders of magnitude more inert. Impressively, the latter complex resists acid decomplexation even better than the fully-encapsulated sarcophagine complex Cu(II)-diamsar. It was confirmed that both the cross-bridged cyclam backbone as well as presence of two enveloping carboxymethyl arms are required for this unusual kinetic inertness.

Table 2.

Pseudo-first order half-lives for acid-decomplexation and reduction potentials of Cu(II) complexes (all values are from Heroux et al. [44] unless otherwise noted).

| Chelator | 5 M HCl 90°C | 12 M HCl 90°C | Ered (V) vs Ag/AgCl |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOTA | <3 min | <3 min | −0.94 (irrev.)a |

| cyclam | <3 min | <3 min | −0.68 (quasi-rev) |

| TETA | 4.5(5) min | <3 min | −1.18 (irrev.) |

| CB-cyclam | 11.7(1) min | <3 min | −0.52 (quasi-rev) |

| CB-TE2A | 154(6) h | 1.6(2) h | −1.08 (quasi-rev.) |

| CB-DO2A | < 3 min | n.d. | −0.92 (irrev.) |

| CB-TE2LA | 100 h | 39(5) min | −0.68 (quasi-rev.) |

| CB-DO2LA | < 3 min | n.d. | −0.78 (irrev.) |

| CB-TEAMA | n.d. | n.d. | −0.96 (quasi-rev.) |

| diamsar | 40(1) h | < 3 min | −1.1 (irrev) |

[34]

The effect of pendant arm length on acid stability was also investigated. Heroux et al. compared the properties of Cu(II) complexes of cross-bridged cyclam and cyclen having N-carboxyethyl pendant arms (CB-DO2LA (14) and CB-TE2LA (15)) to the corresponding CBTE2A and CB-DO2A complexes [44]. The inertness of Cu-CB-TE2LA in 5 N HCl at 90°C of 100 h was very high compared to other chelators, though not quite as good as 154 h for Cu-CB-TE2A (Table 2).

With respect to ease of Cu(II)/Cu(I) reduction, cyclic voltammetric studies of Cu(II) complexes of a variety of tetraazamacrocyclic complexes revealed that Cu-CB-TE2A (16) is not reduced in 0.1 N sodium acetate until a relatively negative potential of −1.07 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) [11]. Further, unlike the Cu-DOTA (19), Cu-TETA (18) and Cu-diamsar cyclic voltammograms, this reduction is quasi-reversible, suggesting the innate ability of the cross-bridged cyclam ligand to adapt to a geometry suitable for Cu(I) coordination [11] (Gustafson L, Wong Edward H. Unpublished results. 2006). The reduction of the Cu-CB-TE2LA was also quasi-reversable, but was 400 mV more easily reduced than Cu-CB-TE2A [44]. Both resistance to proton-assisted decomplexation and the Cu(II)/Cu(I) reduction of Cu-CB-TE2A suggest that the ligand may be an especially promising chelator candidate for 64/67Cu(II).

Biological stability of several of the 64Cu complexes of the CB-macrocycle ligands shown in Fig. (2) has been investigated [34, 43, 48]. The 64Cu complex of CB-TE2A was formed under carrier-added and no-carrier-added conditions in less than 2 h at 55°C [43]. Serum stability experiments indicated that these complexes are stable in rat serum out to 24 h. Results of biodistribution studies of these 64Cu complexes in female Sprague Dawley rats were highly dependent upon the chelator. The complex 64Cu-CB-TE2A was determined to be the most stable and was cleared most rapidly from the blood, liver, and kidney.

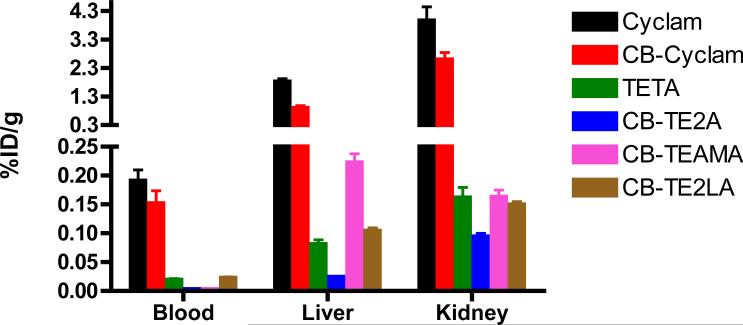

Boswell et al. directly compared the in vivo stability of the 64Cu complexes of CB-TE2A and CB-DO2A (9), which are analogues of TETA and DOTA respectively, and developed the analytical conditions to purify and isolate the kinetic 64Cu-CB-complexes and their metabolic analytes [34, 45]. Both CB-ligands were labeled in high radiochemical purity at 95°C using ethanol and cesium carbonate, followed by the addition of 64CuCl2. These relatively harsh conditions were needed to ensure that the competing reactions between 64Cu and any trace impurity ligands were suppressed. The biodistribution of the 64Cu-CB-DO2A complex was also completed and compared to that of 64Cu-DOTA. At 4 h p.i., 64Cu-CB-DO2A demonstrated significantly better clearance properties than the 64Cu-DOTA analogue. Metabolism studies in normal rats were also conducted and demonstrated that the CB-ligands are less susceptible to 64Cu transchelation than their non cross-bridged analogues. By 4 h 64Cu-CB-TE2A underwent significantly less transchelation in the liver than 64Cu-TETA (13% vs. 75%), while 64Cu-CB-DO2A underwent less transchelation than 64Cu-DOTA (61% vs. 90%). 64Cu-CB-TE2A was clearly the most stable of all of the 64Cu complexes tested and this was most evident at 20 h, where only 24% of the injected 64Cu was transchelated to proteins; in contrast, 92% of the 64Cu associated with TETA was transchelated. In addition, a survey of biodistribution data of several 64Cu-tetraazamacrocycles in normal rats reveals that 64Cu-CB-TE2A has superior clearance properties as shown in Fig. (4) [34, 43, 46]. These data correspond with the in vitro data, and demonstrate the enhanced in vivo stability that the ethylene cross-bridge and carboxylate pendant arms provide to the tetraazamacrocycles.

Figure 4.

Biodistribution data of selected 64Cu-labeled cyclam and bridged cyclam analogs at 24 h p.i. in normal rats. Adapted from references [43, 44, 46, 48].

Studies also focused upon modifying these CB chelators for conjugation to small molecules and peptides [47]. Sprague et al. confirmed that CB-TE2A will be a valuable BFC for 64Cu. In this study, CB-TE2A was conjugated to the somatostatin analogue Y3-TATE and directly compared to the 64Cu-TETA-Y3-TATE conjugate [47]. 64Cu-CB-TE2A-Y3-TATE was radiolabeled in high radiochemical purity with specific activities of 1.3-5.1 mCi/µg of peptide without the need for harsh labeling conditions. Biodistribution studies using AR42J tumors implanted in male Lewis rats revealed that this complex had greater affinity for somatostatin-positive tissues compared to the TETA conjugate. Accumulation of 64Cu-TE2A-Y3-TATE was lower at all time points in blood and liver, and less accumulation was observed in the kidney at earlier time points when compared to 64Cu-TETA-Y3-TATE. These data suggest that the 64Cu-CB-TE2A-Y3-TATE is more resistant to transchelation than the TETA analogue.

To further examine the stability of cross-bridged macrocycles with one carboxylate and one amide group, a series of Cu(II) complexes of cross-bridged macrocyclic chelators (CBTEAMA (11), CB-MeTEAMA (12), and PhTEAMA (13)) were synthesized and evaluated as model compounds for 64Cu-CB-TE2A-peptide conjugates. The biological behavior of the 64Cu complexes was evaluated in normal rats [48]. These agents showed rapid blood clearance and relatively low liver uptake at 24 h post-injection, demonstrating that one carboxylate is likely to be sufficient for in vivo stability. In addition, Cu-TEAMA showed a highly negative, quasi-reversible reduction potential (−0.96 V) (Wong et al., unpublished results), which is consistent with the in vivo results.

Conclusion

The development, production, and use of 64Cu as a radionuclide for diagnostic imaging and therapy have greatly increased over the last decades. Because of the choice of copper isotopes with variable emission types and energies, it has become essential to develop ligand systems that can stably complex 64Cu to form kinetically inert radiometal complexes. To accomplish this goal, the importance of improved ligand design and synthesis as well as the employment of rigorous physical and biological screening processes to evaluate their in vivo effectiveness is highly essential for the future development of 64Cu radiopharmaceuticals as practical diagnostic imaging and/or radiotherapeutic agents.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge NIH grants R01 CA093375 (to EHW, CJA and GRW) and F32 CA115148 (to TJW).

Abbreviations

- BAT

bromoacetamidobenzyl

- BFC

bifunctional chelator

- CB

cross-bridged

- CB-DO2A

4,10-bis(carboxymethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazabicyclo[5.5.2]tetradecane

- CB-TE2A

4,11 - bis(carboxymethyl)-1,4,8,11-tetraazabicyclo[6.6.2]hexadecane

- Ci

curie

- diamsar

3,6,10,13,16,19-hexaazabicyclo[6.6.6]eicosane-1,8-diamine

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7, 10-tetraacetic acid

- h

hour(s)

- mCi

millicurie

- mmole

millimole

- OC

octreotide

- PET

positron emission tomography

- p.i.

post injection

- SOD

superoxide di smutase

- SUV

Standard uptake value

- TETA

1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane-1,4,8, 11-tetraacetic acid

- V

volts

- Y3-TATE

tyrosine-3-octreotate

References

- 1.Anderson CJ, Welch MJ. Radiometal-labeled Agents (non-Technetium) for Diagnostic Imaging. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2219–34. doi: 10.1021/cr980451q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linder MC. Biochemistry of Copper. Plenum Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linder MC, Hazegh-Azam M. Copper Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. American J Clin Nutr (SUPPL) 1996;63:797s–811s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frieden E. Perspectives on Copper Biochemistry. Clin Physiol Biochem. 1986;4:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zinn KR, Chaudhuri TR, Cheng TP, Morris JS, Meyer WA. Production of No-Carrier-Added Cu-64 from Zinc Metal Irradiated under Boron Shielding. Cancer. 1994;73:774–78. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3+<774::aid-cncr2820731305>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szelecsenyi F, Blessing G, Qaim SM. Excitation function of proton induced nuclear reactions on enriched 61Ni and 64Ni: possibility of production of no-carrier-added 61Cu and 64Cu at a small cyclotron. Appl Radiat Isot. 1993;44:575–80. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy DW, Shefer RE, Klinkowstein RE, Bass LA, Margenau WH, Cutler CS, et al. The Efficient Production of High Specific Activity Cu-64 Using a Biomedical Cyclotron. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(96)00157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obata A, Kasamatsu S, McCarthy DW, Welch MJ, Saji H, Yonekura Y, et al. Production of therapeutic quantities of 64Cu using a 12 MeV cyclotron. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:535–39. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(03)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meares CF. Chelating agents for the binding of metal ions to antibodies. Nucl Med Biol. 1986;13:311–18. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(86)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun X, Anderson CJ. Production and applications of copper-64 radiopharmaceuticals. Meth Enzymol. 2004;386:237–61. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)86011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodin KSHK, Boswell CA, Wong EH, Weisman GR, Niu W, Tomellini SA, Anderson CJ, Zakharov LN, Rheingold AL. Kinetic inertness and electrochemical behavior of Cu(II) tetraazamacrocyclic complexes: possible implications for in vivo stability. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2005;23:4829–4833. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole WC, DeNardo SJ, Meares CF, McCall MJ, DeNardo GL, Epstein AL, et al. Serum Stability of 67Cu Chelates: Comparison with 111In and 57Co. Nucl Med Biol. 1986;13:363–68. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(86)90011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busch DH. The Compleat Coordination Chemistry. One Practitioner's Perspective. Chem Rev. 1993;93:847–60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riesen A, Zehnder M, Kaden TA. Structure of the barium salt of a Cu2+ complex with a tetraaza macrocyclic tetraacetate. Acta Crystallogr. 1988;C44:1740–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riesen A, Zehnder M, Kaden TA. Synthesis, properties, and structures of mononuclear complexes with 12-and 14-membered tetraazamacrocycle-N, N′, N″, N‴-tetraacetic acids. Helv Chim Acta. 1986;69:2067–73. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Y, Zhang X, Xiong Z, Chen Z, Fisher DR, Liu S, et al. microPET imaging of glioma integrin αvβ3 expression using 64Cu-labeled tetrameric RGD peptide. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1707–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McQuade P, Miao Y, Yoo J, Quinn TP, Welch MJ, Lewis JS. Imaging of Melanoma Using 64Cu-and 86Y-DOTA-ReCCMSH(Arg11), a Cyclized Peptide Analogue of a-MSH. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2985–92. doi: 10.1021/jm0490282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, Hou Y, Tohme M, Park R, Khankaldyyan V, Gonzales-Gomez I, et al. Pegylated Arg-Gly-Asp peptide: 64Cu labeling and PET imaging of brain tumor alphavbeta3-integrin expression. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1776–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X, Liu S, Hou Y, Tohme M, Park R, Bading JR, et al. MicroPET imaging of breast cancer alphav-integrin expression with 64Cu-labeled dimeric RGD peptides. Mol Imaging Biol. 2004;6:350–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Sievers E, Hou Y, Park R, Tohme M, Bart R, et al. Integrin alpha v beta 3-targeted imaging of lung cancer. Neoplasia. 2005;7:271–9. doi: 10.1593/neo.04538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li WP, Lewis JS, Kim J, Bugaj JE, Johnson MA, Erion JL, et al. DOTA-D-Tyr1-Octreotate: a somatostatin analog for labeling with halogen and metal radionuclides for cancer imaging and therapy. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:721–28. doi: 10.1021/bc015590k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson CJ, Pajeau TS, Edwards WB, Sherman ELC, Rogers BE, Welch MJ. In vitro and in vivo Evaluation of Copper-64-Labeled Octreotide Conjugates. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:2315–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson CJ, Jones LA, Bass LA, Sherman ELC, McCarthy DW, Cutler PD, et al. Radiotherapy, Toxicity and Dosimetry of Copper-64-TETA-Octreotide in Tumor-Bearing Rats. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:1944–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson CJ, Dehdashti F, Cutler PD, Schwarz SW, Laforest R, Bass LA, et al. Copper-64-TETA-octreotide as a PET imaging agent for patients with neuroendocrine tumors. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:213–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cutler PD, Schwarz SW, Anderson CJ, Connett JM, Welch MJ, Philpott GW, et al. Dosimetry Of Copper-64-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody 1A3 As Determined By Pet Imaging Of the Torso. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:2363–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeNardo S, DeNardo G, Kukis D, Mausner L, Moody D, Meares C. Pharmacology of Cu-67-TETA-Lym-1 Antibody in Patients with B Cell Lymphoma. Antibod Immunoconj Radiopharm. 1991;4:36. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis JS, Srinivasan A, Schmidt MA, Anderson CJ. In vitro and in vivo Evaluation of 64Cu-TETA-Tyr3-Octreotate. A New Somatostatin Analogs with Improved Target Tissue Uptake. Nucl Med Biol. 1998;26:267–73. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(98)00105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis JS, Lewis MR, Srinivasan A, Schmidt MA, Wang J, Anderson CJ. Comparison of Four 64Cu-Labeled Somatostatin Analogs in Vitro and in a Tumor-Bearing Rat Model: Evaluation of New Derivatives for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging and Targeted Radiotherapy. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1341–47. doi: 10.1021/jm980602h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis JS, Laforest R, Buettner TL, Song S-K, Fujibayashi Y, Connett JM, et al. Copper-64-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone):An agent for radiotherapy. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1206–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moi MK, Meares CF, McCall MJ, Cole WC, DeNardo SJ. Copper Chelates as Probes of Biological Systems: Stable Copper Complexes with a Macrocyclic Bifunctional Chelating Agent. Anal Biochem. 1985;148:249–53. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90653-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philpott GW, Dehdashti F, Schwarz SW, Connett JM, Anderson CJ, Zinn KR, et al. RadioimmunoPET (MAb-PET) with Cu-64-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody (MAb 1A3) Fragments [F(ab′)2] in Patients with Colorectal Cancers. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:9P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang M, Caruano AL, Lewis MR, Meyer LA, VanderWaal RP, Anderson CJ. Subcellular Localization of Radiolabeled Somatostatin Analogues: Implications for Targeted Radiotherapy of Cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6864–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bass LA, Wang M, Welch MJ, Anderson CJ. In vivo Transchelation of Copper-64 from TETA-octreotide to Superoxide Dismutase in Rat Liver. Bioconjug Chem. 2000;11:527–32. doi: 10.1021/bc990167l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boswell CA, Sun X, Niu W, Weisman GR, Wong EH, Rheingold AL, et al. Comparative in vivo stability of copper-64-labeled cross-bridged and conventional tetraazamacrocyclic complexes. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1465–74. doi: 10.1021/jm030383m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weisman GR, Rogers ME, Wong EH, Jasinski JP, Paight ES. Cross-Bridged Cyclam. Protonation and Li+ Complexation in a Diamond-Lattice Cleft. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:8604–05. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weisman GR, Wong EH, Hill DC, Rogers ME, Reed DP, Calabrese JC. Synthesis and transition-metal complexes of new cross-bridged tetraamine ligands. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1996:947–48. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hubin TJ, McCormick JM, Collinson SR, Alcock NW, Busch DH. Ultra rigid cross-bridged tetraazamacrocycles as ligands -the challenge and the solution. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1998:1675–76. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hubin TJ, McCormick JM, Alcock NW, Clase HJ, Busch DH. Crystallographic Characterization of Stepwise Changes in Ligand Conformation as their Internal Topology Changes and Two Novel Cross-Bridged Tetraazamacrocyclic Copper(II) Complexes. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:4435–46. doi: 10.1021/ic990491s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hubin TJ, Alcock NW, Morton MD, Busch DH. Synthesis, structure, and stability in acid of copper(II) and zinc(II) complexes of cross-bridged tetraazamacrocycles. Inorgan Chim Acta. 2003;348:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niu W, Wong EH, Weisman GR, Zakharov LN, Incarvito CD, Rheingold AL. Copper(II) and zinc(II) complexes of amide pendant-armed cross-bridged tetraamine ligands. Polyhedron. 2004;23:1019–25. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hubin TJ, Alcock NW, Busch DH. Copper(I) and copper(II) complexes of an ethylene cross-bridged cyclam. Acta Crystallogr. 2000;C56:37–39. doi: 10.1107/s010827019901255x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong EH, Weisman GR, Hill DC, Reed DP, Rogers ME, Condon JP, et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Cross-Bridged Cyclams and Pendant-Armed Derivatives and Structural Studies of their Copper(II) Complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:10561–72. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun X, Wuest M, Weisman GR, Wong EH, Reed DP, Boswell CA, et al. Radiolabeling and in vivo behavior of copper-64-labeled cross-bridged cyclam ligands. J Med Chem. 2002;45:469–77. doi: 10.1021/jm0103817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heroux KJ, Woodin KS, Tranchemontagne DJ, Widger PC, Southwick E, Wong EH, et al. The long and short of it: the influence of N-carboxyethyl versus N-carboxymethyl pendant arms on in vitro and in vivo behavior of copper complexes of cross-bridged tetraamine macrocycles. Dalton Trans. 2007:2150–62. doi: 10.1039/b702938a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boswell CA, McQuade P, Weisman GR, Wong EH, Anderson CJ. Optimization of labeling and metabolite analysis of copper-64-labeled azamacrocyclic chelators by radio-LC-MS. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones-Wilson TM, Deal KA, Anderson CJ, McCarthy DW, Kovacs Z, Motekaitis RJ, et al. The in vivo Behavior of Copper-64-Labeled Azamacrocyclic Compounds. Nucl Med Biol. 1998;25:523–30. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(98)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sprague JE, Peng Y, Sun X, Weisman GR, Wong EH, Achilefu S, et al. Preparation and biological evaluation of copper-64-Tyr3-octreotate using a cross-bridged macrocyclic chelator. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8674–82. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sprague JE, Peng Y, Fiamengo AL, Woodin KS, Southwick EA, Weisman GR, et al. Synthesis, characterization and in vivo studies of Cu(II)-64-labeled cross-bridged tetraazamacrocycle-amide complexes as models of peptide conjugate imaging agents. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2527–35. doi: 10.1021/jm070204r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]