Abstract

Background

Little is known about short-duration episodes of mania-like symptoms in youth. Here we determine the prevalence, morbid associations, and contribution to social impairment of a phenotype characterised by episodes during which symptom and impairment criteria for mania are met, but DSM-IV duration criteria are not (Bipolar not otherwise specified; BP-NOS).

Methods

A cross-sectional national survey of a sample (N=5326) of 8-19 year olds from the general population using information from parents and youth. Outcome measures were prevalence rates and morbid associations assessed by the Developmental and Well-Being Assessment, and social impairment assessed by the impact scale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

Results

While only seven individuals (0.1%) met definite or probable DSM-IV criteria for BPI or BPII, the prevalence of BP-NOS was 10-fold higher, 1.1% by parent report and 1.5% by youth report. Parent-youth agreement was very low: κ=0.02, p>0.05 for BP-NOS. Prevalence and episode duration for BP-NOS did not vary by age. BP-NOS showed strong associations with externalising disorders. After adjusting for a dimensional measure of general psychopathology, self-reported (but not parent-reported) BP-NOS remained associated with overall social impairment.

Conclusions

BP meeting full DSM-IV criteria is rare in youth. BP-NOS, defined by episodes shorter than those required by DSM-IV, but during which DSM-IV symptom and impairment criteria are met, is commoner and may be associated with social impairment that is beyond what can be accounted for by other psychopathology. These findings support the importance of research into these short episodes during which manic symptoms are met in youth but they also call into question the extent to which BP-NOS in youth is a variant of DSM-IV BP - superficially similar symptoms may not necessarily imply deeper similarities in aetiology or treatment response.

Keywords: Bipolar Disorder, Manic Episodes, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder

Introduction

The rate of diagnosis of bipolar disorder (BP) in children and adolescents has increased dramatically over the last decade (Blader and Carlson, 2007, Moreno et al., 2007), becoming a matter of intense debate, especially in the United States (Carlson and Meyer, 2006, Leibenluft, Charney, Towbin, Bhangoo and Pine, 2003). Traditionally, BP has been thought to be exceedingly rare in children(Goodwin and Jamison, 2007). Consistent with this view, the only recent, reasonably-sized US epidemiological study to examine BP prevalence in youth found no cases of mania and an 0.1% prevalence of hypomania in children up to age 13 (Costello et al., 1996). However, the question has been raised as to whether the duration criteria required by DSM-IV definitions of mania or hypomania (i.e. episodes of at least 7 and 4 days duration, respectively) (APA, 2000) are developmentally inappropriate for children, and whether BP in youth should therefore be diagnosed on the basis of episodes of shorter duration, or by re-defining the relationship between episodes and cycles (Geller, Tillman and Bolhofner, 2007). In support of less restrictive duration criteria, a prospective clinic study found that approximately 25% of youth with episodes too short to meet DSM-IV criteria for mania or hypomania developed BPI within two years (Birmaher et al., 2006). Epidemiological studies in adults also suggest that hypomanic episodes lasting 1-3 days may be on a continuum with classical BP (Angst et al., 2003).

This paper is an epidemiological investigation in youth of episodes of manic symptoms that meet DSM-IV symptom and impairment criteria but persist for less than four days. Leaning on previous empirical work (Axelson et al., 2006), common DSM-IV practice, and guidelines of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP; (McClellan, Kowatch and Findling, 2007)), we designated such short episodes as bipolar not otherwise specified (BP-NOS). Given that irritability is a widespread and less-specific symptom in youth, we required that elation, rather than elation or irritability, be present in order for an episode to meet DSM-IV's “criterion A” for manic episodes. Since elated mood is present in the great majority of youth with BP (92% for BPI and 82% for BP-NOS (Axelson et al., 2006)), it seems unlikely that many true cases of BP will be lost by stipulating elation, but not irritability, as the A criterion.

We tested three hypotheses

Firstly, that the prevalence of BP-NOS would be markedly higher than that of BPI or BPII in youth. This is based on studies in adults, where relaxing the duration criterion leads to a substantial increase in the prevalence of hypomania (Angst et al., 2003). This would also be in agreement with findings from a community sample of adolescents (Lewinsohn, Klein and Seeley, 1995), where relaxed duration and symptom-count criteria led to higher prevalence rates.

Secondly, we sought to determine the associations of BP-NOS with other disorders in youth. Previous clinic studies (Axelson et al., 2006) have found high rates of comorbidity between BP-NOS and externalising disorders of childhood, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder. We expected to confirm this pattern in our community-based study.

Thirdly, we wanted to establish whether BP-NOS contributed to overall social impairment in youth, beyond that explained by comorbid psychopathology and substance use. The validity of the BP-NOS category would be supported by an association with overall impairment, independent of other childhood psychopathology or substance use.

Method

Population

The 2004 British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey (B-CAMHS04) was carried out in 2004 on a representative group of 5-16 year olds (N=7977). The design of the B-CAMHS04 survey has been described in detail (Green, McGinnity, Meltzer, Ford and Goodman, 2005). “Child benefit” is a universal state benefit payable in Great Britain for each child in the family. The child benefit register was used to develop a sampling frame of postal sectors from England, Wales, and Scotland that, after excluding families with no recorded postal code, was estimated to represent 90% of all British children. Of the 12,294 recruited, 1,085 opted out and 713 were ineligible or had moved without trace, leaving 10,496 who were approached. Of those, 7,977 participated (65% of those selected; 76% of those approached). Three years after the original survey (i.e. in 2007), families were approached again unless they had previously opted out or the child was known to have died. Of the original 7,977, 5,326 (67%) participated in the detailed follow-up(Parry-Langdon, 2008).

Measures

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) is a 25-item questionnaire with robust psychometric properties (Bourdon, Goodman, Rae, Simpson and Koretz, 2005, Goodman, 1997, Goodman, 2001). It was administered to parents and youth and used to generate an SDQ total symptoms score (reflecting hyperactivity, inattention, behaviour problems, emotional symptoms and peer problems). The SDQ symptom items do not contain items on elated or expansive mood.

In addition, we used the SDQ total impact score, a measure of overall distress and social impairment due to all mental health problems (Goodman and Scott, 1999). It specifically enquires about impairment in the domains of family, school, learning and leisure. Hereafter, we refer to this score as social impairment.

The Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA) was used in the survey and has been described extensively previously (Ford, Goodman and Meltzer, 2003, Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward and Meltzer, 2000). It is a structured interview administered by lay interviewers. The questions are closely related to DSM-IV (American Psychiatric, 2000) diagnostic criteria and focus on current rather than life-time problems. The κ-statistic for chance-corrected agreement between two raters was 0.86 for any disorder (SE 0.04), 0.57 for internalizing disorders (SE 0.11), and 0.98 for externalizing disorders (SE 0.02) (Ford et al., 2003). Children were assigned a diagnosis only if their symptoms were causing significant distress or social impairment. The DAWBA interview was administered to all parents and to all youth aged 11 or over. DSM-IV diagnoses are assigned by integrating the parent, youth and teacher reports on symptoms and impairment as extensively described (Ford et al., 2003). Further information on the DAWBA is available from http://www.dawba.com, including on-line and downloadable versions of the measures and demonstrations of the clinical rating process.

The 2007 survey incorporated questions on elated mood and symptoms of mania that had not been administered in 2004. The complete bipolar section of the interview can be seen at http://www.dawba.com/Bipolar. In summary, the parents of 8-19 year olds and the 11-19 year olds themselves were presented with the following preamble: “Some young people have episodes of going abnormally high. During these episodes they can be unusually cheerful, full of energy, speeded up, talking fast, doing a lot, joking around, and needing less sleep. These episodes stand out because the young person is different from their normal self.” They were then asked: “Do you [Does X] ever go abnormally high?”, to which they had the options of answering: No, A little, A lot. Those who answered “A little” or “A lot” were asked 26 more questions about specific symptoms of mania, including those stipulated by DSM-IV(APA, 2000), that may occur during such episodes of going high. BP was diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria, although no distinctions between BP-I (which requires the presence of at least one episode of mania) and BP-II (which requires the presence of depression and at least one episode of hypomania) were made and, accordingly, there was no requirement for the presence of a depressive episode; hence, the minimum required duration was 4 days. The DSM-IV and ICD-10 largely overlap with regard to symptom criteria. Here we refer explicitly to the DSM-IV in order to facilitate comparability with studies in the US, where the bipolar debate has originated. The category we designated BP-NOS, was defined by the following requirements:

Distinct episodes involving elevated or expansive mood (not just irritable mood), by answering “a little” or “a lot” to the screening question.

The individual meets at least three of the seven B criteria for DSM-IV mania during these episodes.

The episodes result in impairment, as judged by interference with family functioning, friendship, learning, or leisure.

The typical duration of these episodes is more than one hour and less than four days.

For the purposes of further subanalyses, we divided the BP-NOS group into those with episodes lasting between 1 hour and less than one day and those with episodes lasting at least one day but less than 4 days.

Preliminary validation

The bipolar section was administered to the parents of 5,254 children in the community sample and also to the parents of 14 children with a clinical diagnosis of BP who attended an outpatient pediatric psychopharmacology clinic. The community and clinic samples did not differ significantly in age or gender. The mean score of manic symptoms (summing the S4, S5 and S6 questions on http://www.dawba.com/Bipolar) was 2.9 (SD=8.6) for the community sample as compared with 37.1 (SD=12.1) for the clinic sample (t=10.6, 13.0 df, p<0.001). In a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis using the manic symptoms score to predict membership of the clinic group, the area under the curve (AUC) was 0.98 (95% confidence interval 0.96 to 0.99). As a guide to interpretation, the AUC would have been 0.50 if the symptom score had no predictive value and 1.00 if the symptom score had been a perfect predictor.

In the 2007 survey, youth aged 11 and above where asked about their use of alcohol and illicit drugs. For the purposes of the analyses reported here, we define moderate to heavy substance use by one or more of the following: alcohol use almost every day; cannabis use more than once per week; ecstasy use on more than 5 occasions; amphetamine use on more than 5 occasions; or cocaine use on more than 5 occasions.

Analysis

The rate of participation was lower for children and young people with the baseline characteristics shown in Supplementary Table 1. An inverse propensity score was used to generate sampling weights to adjust for missingness and estimate prevalences. For example, prevalence was calculated as the weighted proportion of those meeting threshold for the construct of parent-reported BP-NOS divided by the total number of study participants with available parent-report. Logistic regression models included DSM-IV diagnoses as the dependent variable and either parent- or self-reported BP-NOS as the independent variable. Linear regression models included the SDQ total impact score as the dependent variable and either parent- or self-reported BP-NOS, along with substance use and the SDQ total difficulties score, as independent variables. STATA Version 10 (StataCorp, 2007) was used.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Central Office for Research Ethics Committees (COREC) of the United Kingdom. Children provided assent for their own participation, but could not veto their parents' participation on the basis of the parents' informed consent.

Results

Approximately 2.0% of the 2007 sample reported drinking alcohol almost every day, 2.3% used cannabis more than once per week, 1.3% used ecstasy on more than 5 occasions, 0.7% used amphetamine on more than 5 occasions, and 0.7% used cocaine on more than 5 occasions. Approximately 4.7% reported one or more of the above – referred to subsequently as moderate to heavy substance use.

Two individuals met the full DSM-IV criteria for recurrent hypomanic or manic episodes. Five other individuals met criteria by parent or child report, although there were inconsistencies between or within informants about duration, symptoms or impact. Thus, the overall prevalence for DSM-IV BP in the total sample of 8-19 year olds was between 0.04% and 0.13%. Both of the definite cases were in the 16-19 year age range, as were four of the five probable cases; the prevalence of DSM-IV BP in the 16-19 year olds in the sample was thus between 0.1% and 0.3%. Only one of the 8-15 year olds (N=3618) met criteria for DSM-IV BP. Of the seven individuals with definite or probable BP I or II according to DSM-IV criteria, four individuals had a concurrent internalizing disorder (three with anxiety plus depression, and one with just anxiety) and a further two individuals had conduct disorders. The small numbers precluded meaningful further analyses.

A substantial proportion of respondents endorsed the screening question about distinct episodes of elevated or expansive mood. By parent report, 10.5% were mildly screen positive (replying “a little” to the screening question) and a further 2.2% were strongly screen positive (replying “a lot” to the screening question). By youth report, 23% were mildly screen positive and a further 5% were strongly screen positive.

Prevalence of episodes qualifying for BP-NOS was 1.1% (58/5247) and 1.5% (48/3295) according to parent and youth report respectively. Boys made up 64% of those assigned BP-NOS as judged by parent report and 42% of those assigned BP-NOS as judged by youth report; neither proportion differed significantly from the sample as a whole. By parent report, the mean age of those with BP-NOS was 12.8 (SD=3.4) years as compared to 13.4 (SD=3.3) years for those without (not significant), whereas by youth report, the mean age of those with BP-NOS was 13.7 (SD=1.7) years as compared to 14.8 (SD=2.4) years for those without (p<0.01). Kappas for inter-rater agreement between parent- and youth-rated BP-NOS were 0.02 (not significant).

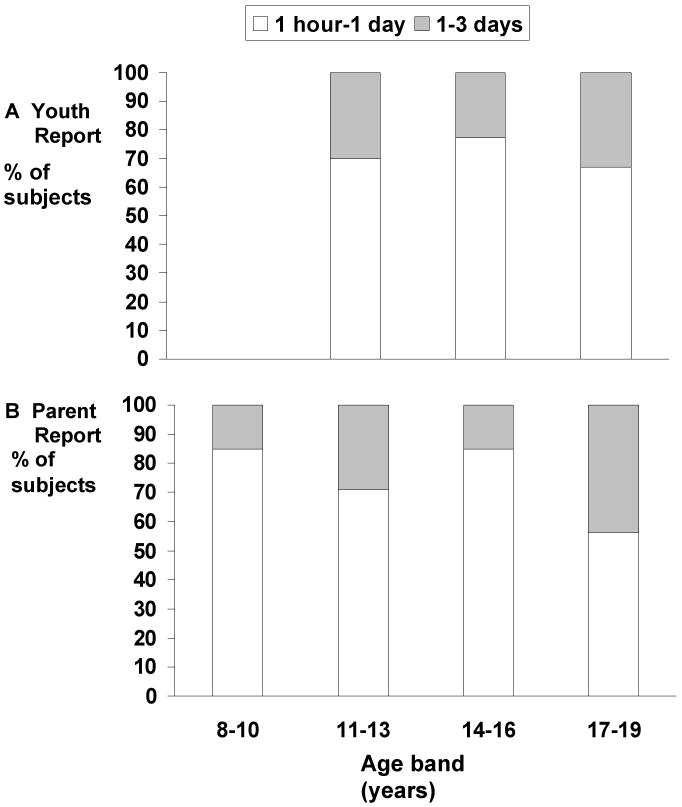

The relationship between episodes of elated mood with age is shown for each informant in Figure 1. For those with BP-NOS according to parent or youth report, there was no significant association of episode duration with age across the 8-19 year age span: for youth report (only available from the age of 11), the Spearman correlation between age (banded) and duration (banded) was -0.06 (p=0.70); the corresponding correlation for parent report was 0.15 (p=0.29).

FIGURE 1. Relationship of episodes of elated mood with age.

Typical duration of an episode of going high as reported for children and adolescents with BP-NOS, shown separately for youth and parent report according to age bands.

Table 1 presents the comorbid associations of BP-NOS by parent and youth report. Parent-reported BP-NOS showed particularly strong associations with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct or oppositional defiant disorder (CD/ODD) as well as pervasive developmental disorder (PDD). Youth-reported BP-NOS was significantly associated with CD/ODD, ADHD and anxiety disorders. Neither parent nor youth-reported BP-NOS were associated with depression.

TABLE 1.

Comorbid associations of BP-NOS by reporting source.

| Any Disorder | ADHD | CD/ODD | Depression | Anxiety | PDD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-based diagnosis of BP-NOS (n=58) | % (N) OR CI |

72 (41) 24.6 (13.0 to 46.4.)*** |

29 (17) 31.5 (15.7 to 63.4)*** |

50 (29) 21.1 (11.6 to 38.4)*** |

4 (2) 4.1 (0.9 to 17.6) |

9 (5) 2.5 (0.9 to 6.6) |

12 (7) 16.3 (5.6 to 47.3)*** |

| Youth-based diagnosis of BP-NOS (n=48) | % (N) OR CI |

37 (18) 6.4 (3.4 to 12.0)*** |

6 (3) 6.0 (1.7 to 20.6)** |

22 (11) 7.3 (3.4 to 15.8)*** |

4 (2) 2.4 (0.3 to 18.5) |

13 (6) 3.8 (1.6 to 9.3)** |

0 - |

p<0.001

p<0.01 in logistic regression models.

BP-NOS, assigned based on either parent or youth report, was significantly associated with social impairment, as judged by the SDQ total impact score (Table 3). The associations remained significant after adjusting for comorbidity with anxiety disorders, depression, ADHD, CD/ODD and PDD. Youth-reported BP-NOS remained a significant predictor of social impairment even after further adjustment using the SDQ total symptoms score. Parent-reported BP-NOS was no longer significantly associated with impairment after these adjustments. Repeating these analyses after adjusting for moderate to heavy substance did not change the pattern of associations (results available from the authors upon request).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of episode duration within BP-NOS.

| Episode Duration | Comorbidity Rate† % | Total SDQ Symptom Score‡ | Total SDQ Impact Score‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-based diagnosis of BP-NOS | 1hour – 1day n=44 |

72 | 20.4 (6.2) | 3.2 (2.3) |

| 1 day – 3 days n=14 |

71 | 20.4 (6.5) | 2.0 (1.9) | |

| χ2 = 0.02, p=0.96 | t=-0.033, df=56, p=0.97 | t=-1.74, df=56, p=0.09 | ||

| Youth-based diagnosis of BP-NOS | 1hour – 1day n=36 |

33 | 15.6 (5.0) | 1.3 (1.6) |

| 1 day – 3days n=12 |

46 | 17.6 (6.1) | 1.7 (2.1) | |

| χ2 = 0.68, p=0.41 | t=-1.1, df=46, p=0.27 | t=-0.68, df=46, p=0.50 |

The two different episode categories comprising BP-NOS are compared for each parent and youth report. The comorbidity (overlap with other DSM-IV disorder) rates are presented as percentages;

denotes chi-square testing

denotes two-sided t-test.

Episodes lasting between 1 hour and 1 day did not differ significantly from episodes lasting between 1 day and 3 days with respect to rates of comorbidity, total SDQ symptom score and overall social impairment (Table 3).

Discussion

We used parent- and self-reported data from a national community survey of 8-19 year olds to examine the prevalence and correlates of BP-NOS, defined as meeting DSM-IV symptom and impairment criteria for mania during episodes lasting less than 4 days. Recurrent episodes of mania or hypomania meeting DSM criteria for episode duration were rare and almost completely restricted to 16-19 year olds. Even in this late teenage range, the prevalence was only in the 0.1%-to-0.3% range.

To our knowledge, this is the first epidemiologic study to report on the prevalence of children and adolescents meeting symptom and impairment criteria for mania during episodes of short duration. Previous reports on subthreshold symptoms in adolescents (Carlson and Kashani, 1988, Johnson, Cohen and Brook, 2000, Lewinsohn, Seeley and Klein, 2003) as well as most other epidemiologic studies were conducted before the onset of the debate on BP in children and adolescents (Costello et al., 1996, Goodwin and Jamison, 2007, Verhulst, van der, Ferdinand and Kasius, 1997). It is perhaps indicative of the prevalence expectations for BP among European child psychiatrists that several landmark studies have decided against ascertaining it as a diagnostic outcome (Fombonne, 1994, Steinhausen, Metzke, Meier and Kannenberg, 1998, Wittchen, Nelson and Lachner, 1998, Esser, Schmidt and Woerner, 1990). By insisting on the elation criterion, our study avoids problems estimating rates of BP-NOS by including episodes of pure irritability—a frequently expressed concern in the current discussion about BP (Carlson, 2007, Geller et al., 2007, Leibenluft et al., 2003). While DSM-IV BP was rare, the shorter episodes of elated mood we labeled BP-NOS was considerably more common. In view of its relatively high prevalence, the question as to whether BP-NOS represents a valid disorder is of considerable relevance to service planning as well as to clinicians and families.

The association of BP-NOS with other disorders was more pronounced by parent than by self report; however, regardless of reporting source, CD/ODD showed the highest rates of co-occurrence with BP-NOS. This confirms previous findings about the comorbidity between BP-NOS and externalizing disorders (Axelson et al., 2006). Previous accounts of BP in youth have questioned the validity of the bipolar diagnosis in children (Carlson and Meyer, 2006, Harrington and Myatt, 2003, Moreno et al., 2007), raising the concern that what is labeled BP in youth, especially in cases that do not meet the DSM-IV duration criterion, may simply be an epiphenomenon of other, mainly externalising, childhood disorders, or of moderate to heavy substance use. If this were so, then we anticipated that the presence of BP-NOS should be unrelated to social impairment once allowance was made for comorbid psychopathology or moderate to heavy substance use. We found that for both youth- and parent-reported BP-NOS, adjustment for comorbid diagnoses and substance use reduced but did not eliminate the association between BP-NOS and social impairment. This suggests that BP-NOS may represent clinically relevant psychopathology and is not necessarily just a consequence of other DSM-IV diagnoses. In addition, it makes it unlikely that BP-NOS is the result of drug- or alcohol-induced elation. To reduce the risk of making too little allowance for comorbid symptoms that are present and meaningful, even if they don't meet threshold for diagnosis, we then adjusted for dimensional measures of psychopathology (SDQ total symptom scores) as well as psychiatric diagnoses. Only self-reported BP-NOS remained significant after this further adjustment. The fact that prediction from parent-reported BP-NOS to social impairment was rendered non-significant casts some doubt on the validity of parent-reported BP-NOS, but could also be due to our having over-adjusted by making too much allowance for comorbid psychopathology.

We find that no clear distinctions can be drawn between episodes lasting between 1 hour and 1 day, and those lasting between 1 and 3 days in terms of their association with the SDQ total-symptom- and impairment-scores. This mirrors findings in the adult literature (Angst et al., 2003). It should be emphasized, however, that this lack of difference by no means excludes the possibility that these associations are non-specific, rather than an indication of equivalence of manic symptomatology.

Using the term BP-NOS to describe short episodes of manic symptoms implies that the condition is on a spectrum with BPI and BPII. In support of this, one clinical study showed that 25% of youth with BP-NOS developed DSM-IV BP within the following 2 years (Birmaher et al., 2006) However, it should be noted that this study (Birmaher et al., 2006) required a minimum episode duration of 4 hours, as well as four cumulative lifetime days, in order to meet the criteria for BP-NOS, which is higher than the minimum duration that was required here. In addition, this study was on a clinic-based sample of youth presenting for treatment, rather than a community sample. A previous community study of adolescents found that “subthreshold” BP, diagnosed using relaxed criteria for duration and symptom number, was associated with impairment and a family history of BP (Lewinsohn, Klein, Durbin, Seeley and Rohde, 2003). Indeed, considerations about where to draw the boundaries of BP, in terms of episode duration, are ongoing even in the adult literature. In adults, epidemiological studies suggest that subthreshold BP is common, impairing and probably on a continuum with BPI and II (Angst et al., 2003, Merikangas et al., 2007): episodes of mania-like symptoms lasting between 1 to 3 days are indistinguishable from episodes lasting 4 days or more with respect to their clinical correlates (Angst et al., 2003). Similarly, episodes of mania-like symptoms lasting 2-6 days did not differ in outcome compared to episodes lasting 7 days or longer (Judd et al., 2003).

On the other hand, some of our findings do not support the conclusion that BP-NOS, as defined here, is on a continuum with DSM-IV BP I or II. In our sample of 8-19 year olds, the prevalence of BP-NOS was almost the same across the entire age span, and so too was the typical duration of reported episodes. The lack of age trends is contrary to what one might expect if short episodes of elation in childhood became progressively longer as the individual matures, eventually becoming long enough to meet DSM-IV duration criteria by late adolescence or early adulthood. In addition, and in keeping with previous results (Thuppal, Carlson, Sprafkin and Gadow, 2002, Tillman et al., 2004), we found that parent-youth agreement for BP-NOS was no better than chance. This raises the possibility that parents and youths are reporting on two rather different constructs, even if they are being asked the same questions. This finding suggests particular caution when attempting to combine information from the two reporting sources using, for example, an “or” rule as is frequently done in child and adolescent psychiatry. Finally, it is notable that BP-NOS showed no significant associations with depression by either informant. However, given that our survey focuses on depressive symptoms over the last month, rather than lifetime symptoms, these findings might represent an underestimate of the true association. Overall, however, our findings call into question the extent to which BP-NOS in youth really is a variant of DSM-IV BP; superficially similar symptoms may not necessarily imply deeper similarities in aetiology or treatment response Since clinical diagnoses of bipolar disorder in youth appear to be increasing in the USA (Blader and Carlson, 2007) and elsewhere (Holtmann, 2008), future research should continue to examine whether unequivocal bipolar disorder can be distinguished from manifestations that bear clinical similarities, but may be pathophysiologically distinct. Alternative conceptualisations, such as that of mood lability in youth (Stringaris and Goodman, 2008), a construct that is associated with a wide range of psychopathology and comorbidity, may therefore be helpful in formulating relevant research questions and avoiding possible semantic confusion. Indeed, our findings of low parent-child rating agreement and a wide association with externalising psychopathology—both suggestive of low diagnostic specificity—seem to mirror those of a previous study on adolescents in the community endorsing manic symptoms of at least two days duration (Carlson and Kashani, 1988).

The analyses presented in this paper use an epidemiological approach to examine a contentious topic. There are two main reasons why these results should be regarded as preliminary. Firstly, although the original sample was recruited from the community, only about two-thirds of those selected actually participated in 2004, and of those who did take part in the 2004 survey, only two-thirds participated in the 2007 follow-up that was the basis of this study. As a result, selective participation both in 2004 and 2007 may have biased our estimates of prevalence and morbid associations. Conceivably, there may have been attrition of cases with BP or BP-NOS and this may result in underestimating their prevalence. We adjusted for drop-out between 2004 and 2007 by using appropriate propensity weights; however it was not possible to adjust in a similar way for incomplete participation in 2004, since detailed information on non-participants was not available. A second reason for regarding this study as preliminary is that a new measure of BP had to be developed at short notice to fit the constraints of a large epidemiological survey carried out by lay interviewers. While the preliminary validation data are encouraging, more detailed validation is required. Unfortunately, given the uncertain status of BP-NOS, there is no true “gold standard” assessment for establishing criterion validity. We would also like to emphasise that the bipolar section of this instrument is yet to be validated for the purposes of clinical screening and decision making.

Further limitations also apply. We allowed an answer of “a little” to count as endorsement of a distinct episode of elated mood, thus possibly risking over-ascertainment. However, we believe this risk is largely offset by requiring that DSM-IV symptom and impairment criteria are met during the episode. Also, the clinical relevance of bipolar disorders was judged from its association with social impairment as reported by parents or youth, rather than with clinician ratings of social impairment. Our study was cross-sectional requiring caution when drawing aetiological inferences.

Supplementary Material

TABLE 2.

The relation of BP-NOS by parent and youth report to social impairment

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for Comorbid Diagnoses | Adjusted for Comorbid Diagnoses and Psychopathology Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β, (p-value) | β, (p-value) | β, (p-value) | |

| Parent-based diagnosis of BP-NOS (n=58) | 0.202, p<0.001 | 0.057, p<0.01 | 0.022, NS |

| Youth-based diagnosis of BP-NOS (n=48) | 0.175, p<0.001 | 0.147, p<0.001 | 0.112, p<0.01 |

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Department of Health of the British Government.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- American Psychiatric, A. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Gamma A, Benazzi F, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W. Toward a re-definition of subthreshold bipolarity: epidemiology and proposed criteria for bipolar-II, minor bipolar disorders and hypomania. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:133–146. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Bridge J, Keller M. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:1139. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Keller M. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:175. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC, Carlson GA. Increased rates of bipolar disorder diagnoses among U.S. child, adolescent, and adult inpatients, 1996-2004. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:107. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon KH, Goodman R, Rae DS, Simpson G, Koretz DS. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: U.S. normative data and psychometric properties. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:557. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000159157.57075.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA. Who are the children with severe mood dysregulation, a.k.a. “rages”? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1140–1142. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07050830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, Kashani JH. Manic symptoms in a non-referred adolescent population. 1988;15:219. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, Meyer SE. Phenomenology and diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: complexities and developmental issues. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18:939–969. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, Stangl DK, Tweed DL, Erkanli A, Worthman CM. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth. Goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1129. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser G, Schmidt MH, Woerner W. Epidemiology and course of psychiatric disorders in school-age children--results of a longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1990;31:243–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. The Chartres Study: I. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among French school-age children. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164:69–79. doi: 10.1192/bjp.164.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford T, Goodman R, Meltzer H. The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey 1999: the prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:1203. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200310000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Tillman R, Bolhofner K. Proposed definitions of bipolar I disorder episodes and daily rapid cycling phenomena in preschoolers, school-aged children, adolescents, and adults. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17:217. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, Gatward R, Meltzer H. The Development and Well-Being Assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:645–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, Scott S. Comparing the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist: is small beautiful? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:17. doi: 10.1023/a:1022658222914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic Depressive Illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. Epidemiology; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H, Ford T, Goodman R. Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004. London: The Stationery Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington R, Myatt T. Is preadolescent mania the same condition as adult mania? A British perspective. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:961–969. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmann M, Poustka F, Duketis F, Bölte S. Pediatric Bipolar Disorder in Germany: National Trends in the Rates of Inpatients; 8th International Review of Bipolar Disorders (IRBD); Kopenhagen. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brook JS. Associations Between Bipolar Disorder and Other Psychiatric Disorders During Adolescence and Early Adulthood: A Community-Based Longitudinal Investigation. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1679–1681. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser JD, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Keller MB. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:261–269. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, Charney DS, Towbin KE, Bhangoo RK, Pine DS. Defining clinical phenotypes of juvenile mania. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:430. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Durbin EC, Seeley JR, Rohde P. Family study of subthreshold depressive symptoms: risk factor for MDD? J Affect Disord. 2003;77:149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Bipolar disorders in a community sample of older adolescents: prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidity, and course. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Klein DN. Bipolar disorders during adolescence. 2003. p. 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan J, Kowatch R, Findling RL. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:107–125. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242240.69678.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RM, Petukhova M, Kessler RC. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C, Laje G, Blanco C, Jiang H, Schmidt AB, Olfson M. National trends in the outpatient diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in youth. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1032–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry-Langdon N. Three years on: Survey of the emotional development and well-being of children and young people. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen HC, Metzke CW, Meier M, Kannenberg R. Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: the Zurich Epidemiological Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;98:262–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringaris A, Goodman R. Mood lability and psychopathology in youth. Psychol Med. 2008:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuppal M, Carlson GA, Sprafkin J, Gadow KD. Correspondence between adolescent report, parent report, and teacher report of manic symptoms. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12:27–35. doi: 10.1089/10445460252943542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman R, Geller B, Craney JL, Bolhofner K, Williams M, Zimerman B. Relationship of parent and child informants to prevalence of mania symptoms in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1278. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst FC, Van Der EJ, Ferdinand RF, Kasius MC. The prevalence of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a national sample of Dutch adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:329. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160049008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Nelson CB, Lachner G. Prevalence of mental disorders and psychosocial impairments in adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med. 1998;28:109–126. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.