Abstract

During much of the twentieth century, Jersey City, New Jersey was the leading center of chromate production in the United States. Chromate production produced huge volumes of chromium ore-processing residue containing many parts per million of hexavalent chromium. Starting in the 1990s, we undertook a series of studies to identify exposed populations, sources and pathways of exposure and the effectiveness of remediation activities in Jersey City. These studies revealed the effectiveness and success of the remediation activities. The sequence of studies presented here, builds on the lessons learned from each preceding study and illustrates how these studies advanced the field of exposure science in important ways, including the use of household dust as a measure of exposure to contaminants originating in the outdoor environment; development of effective and reproducible dust sampling; use of household dust to track temporal changes in exposure; understanding of the spatial relationship between sources of passive outdoor particulate emissions and residential exposure; use of focused biomonitoring to assess exposure under conditions of large inter-individual variability; and utility of linking environmental monitoring and biomonitoring. For chromium, the studies have demonstrated the use of Cr+6-specific analytical methods for measuring low concentrations of Cr+6 in household dust and understanding of the occurrence of Cr+6 in the background residential environment. We strongly recommend that environmental and public health agencies evaluate sites for their potential for off-site exposure and apply these tools in cases with significant potential as appropriate. This approach is especially important when contamination is widespread and/or a large population is potentially exposed. In such cases, these tools should be used to identify, characterize and then reduce the exposure to the off-site as well as on-site population. Importantly, these tools can be used in a demonstrable and quantifiable manner to provide both clarity and closure to concerned stakeholders.

Keywords: chromium, hexavalent chromium, COPR, dust, biomonitoring, urine

INTRODUCTION

During much of the twentieth century, Jersey City, in Hudson County, New Jersey was the leading center of chromate production in the United States. The process of extracting chromate from chromite ore produced huge volumes of chromium ore-processing residue (COPR), which still contained many parts per million of hexavalent chromium. In addition to being the source of this waste material, Jersey City was also its repository.1 Over a period of decades, the COPR was distributed as landfill throughout Hudson County and surrounding areas. In the late 1980s, the magnitude of this contamination became evident, and it became an environmental health concern, and the subject of a two-day conference at the Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute (EOHSI; February 1990). From the early 1990s to the present, we and our collaborators undertook a series of studies intended to elucidate the occurrence, nature of exposure and effects of COPR for the purposes of identifying exposed populations, sources and pathways of exposure and for assessing the effectiveness of control and remediation activities in Jersey City. Hexavalent chromium contamination at approximately 200 sites was identified, and because of their location near and among residential neighborhoods, potential health risks were identified and required study and remediation.1,2 The large number of sites and the size of the population potentially exposed provided an opportunity to conduct meaningful studies across differing conditions of exposure and over a time period that allowed repeat sampling and comparison of pre- and post-remediation exposure.

Below, we summarize and integrate the findings of the studies we conducted in Jersey City and present them in the context of the development and application of important exposure science tools and concepts, as well as in the context of their application to hazardous waste issues. Taken together, these studies provide a unique opportunity to appreciate the advances and maturation of exposure science. At the same time, this review will illuminate the history of what has been learned about exposure to COPR in what has proved to be one of the largest known cases of community exposure to hazardous waste.

BACKGROUND

In order to provide the context for the exposure and health studies on chromate production waste discussed below, it is helpful to understand the general outline of the chromate production process. Chromium occurs naturally in both the reduced (trivalent) and oxidized (hexavalent) states designated Cr+3 and Cr+6, respectively. The former is an essential trace element with low toxicity, and the latter a carcinogen. Cr+6 has long been recognized as a human inhalation carcinogen,3 and recent evidence also shows it to be carcinogenic by ingestion.4 In addition, Cr+6 is one of the most common and persistent chemical contact allergens.5 Both forms are present in varying concentrations and proportions in chromate waste.

Chromate refers broadly to both chromate () and dichromate () ions, both of which were produced at various times by one or more of the three chromate production plants located in Jersey City. In solution, the two ions can exist in equilibrium and both contribute to the toxicology of the underlying Cr+6 ion. Depending on the specifics of the production process and on the conditions of the soil at the sites of the deposition of COPR, the chromate ions can form a range of salts with various cations. These salts have a range of solubility from highly soluble (e.g., sodium, potassium chromate) to essentially insoluble (e.g., lead chromate). Pulmonary toxicity and carcinogenicity vary among the salts with the moderately insoluble forms having longer retention in the respiratory tract, allowing them to slowly leach Cr+6 into the surrounding tissue.6,7 However, even the relatively insoluble species have toxic activity.

The chromate production process used chromite ore (nominally FeCr2O4, but with possible contributions by Al and Mg), as the starting point. The ore was roasted at high temperature with alkali, sometimes with the addition of lime, and the resulting chromate was extracted with water.8 Neither the roasting nor extraction procedures were quantitative, and the resulting slag could contain percent quantities of Cr+3 and thousands of parts per million of Cr+6. Although this waste slag has been referred to by several different terms, we will refer here to the composite waste material by the commonly encountered terminology, chromium ore-processing residue or COPR. It was apparently not economical for the chromate producers to exhaustively reprocess the slag. At the point where it was no longer economically feasible to further extract chromium, the COPR was disposed of on the company property and in many locations in Jersey City and the surrounding Hudson County where it was used for fill and dikes. Some of the fill locations were eventually used as residential property. This created a patchwork of many waste sites, most of which were in Jersey City, that tended to be clustered in specific neighborhoods. Jersey City is densely populated (approximately 16,000 people per square mile). The large number of sites and the high population density presented a greater potential for exposure than is encountered in many other cases of contaminated sites.

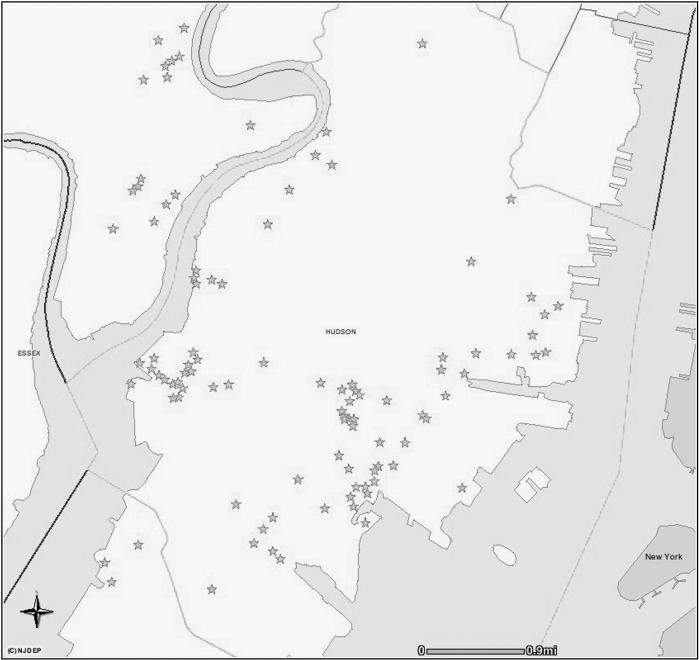

Figure 1 shows a map of the known historic COPR waste sites in Jersey City. In some cases, the waste material was present on the surface, where it was subject to dispersion by wind, adhesion to shoes, clothing and pets and to transport by water. In other cases, where it had been used for below-grade fill, or where it was paved over, the Cr+6 located at depth was particularly subject to subsurface groundwater transport which carried it to foundations and through concrete walls to the interior wall surfaces of basements.1 Thus, there were potentially three pathways of residential exposure: inhalation of particles; ingestion through hand-to-mouth contact; and dermal contact. Exposure could occur outside on waste sites, as well as inside residences where Cr+6-containing particulates were deposited on surfaces through infiltration of outside air, tracking by residents or pets or following seepage through foundations.

Figure 1.

COPR waste sites in and around Jersey City, New Jersey.

The public health challenge of COPR waste sites in Jersey City was exacerbated in the period from 1990 to 2006 by the revitalization of large parts of this once moribund industrial city by the relocation of financial institutions from New York City. This resulted in a real estate boom that precipitated commercial and residential redevelopment in areas previously occupied by industrial facilities. It was not unusual to find that residential buildings were on top of or adjacent to previously remote or unknown COPR sites. In response to increasing concerns about residential exposure as well as in response to new risk assessment approaches to the health effects of Cr+6, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection's (NJDEP) site cleanup criteria changed several times on an interim basis during this period. At the time of this writing, a value of 20 mg Cr+6/kg soil is applied to all sites regardless of their intended use. This value is based on lifetime cancer risk by the inhalation route of exposure. Given new information about the carcinogenicity of Cr+6 by the ingestion route of exposure,4 however, this value may again change to a lower value.

It is against this background that our studies in Jersey City were conducted.

REVIEW OF THE STUDIES

The NJDEP/EOHSI initial investigations set the stage for the 1990 EOHSI Conference on chromium contamination of soil in Jersey City and elsewhere. The conference addressed what was known about the toxicology and epidemiology of Cr+6 and set an agenda for research and risk assessment..2 One of the major challenges identified was the need for reliable and accurate analytic methods for Cr+6 rather than a reliance on measurement of total Cr. Under various real-world conditions Cr+6 and Cr+3 can interconvert. This had been observed in the environment and also in the laboratory, using the standard analytical methodologies for measurement of Cr+6 in environmental samples.9,10 When we initiated this series of studies, there was no reliable analytical method for measurement of Cr+6 in microenvironmental samples (e.g., house dust, air). Thus, for much of the course of these studies, there was no alternative to measurement of total Cr in these samples. The presence of Cr+6 was inferred from these measurements based on the physical relationship of sampled locations to known sources of COPR. However, the need to accurately measure low concentrations of Cr+ in environmental samples for exposure assessment and risk assessment purposes in Jersey City and elsewhere initiated a fruitful area of analytical research that enabled us, toward the latter portion of this series of studies, to specifically measure sub part-per-million concentrations of Cr+6 in microenvironmental samples.

The studies below are presented in chronological order to highlight the logical progression of discovery and refinement that dictated the course of the studies. The studies progressed from initial identification of a hazard, to identification of a route of exposure, to characterization of the exposure, to identification of the susceptible populations and, finally, to documentation of the efficacy of intervention and remediation efforts. The chronological presentation of these studies also highlights the development of the exposure science tools that co-evolved with our understanding of the nature of the exposure. Some of these tools, such as the LWW (Lioy–Weisel–Wainman) dust sampler were developed specifically for the chromium exposure studies, while other tools, such as linkage of biomarkers and physical environmental sampling, were also being developed during this period for similar types of studies of lead and pesticide exposure.

In addition to presenting the rationale, structure, and methodology of each study and summarizing its findings, we also show the lessons we learned from the study that guided subsequent efforts and/or contributed to the development of exposure science.

“Microenvironmental Analysis of Residential Exposure to Chromium-Laden Wastes in and Around New Jersey Homes”11

This was the first study designed to investigate the occurrence and extent of exposure to COPR in Jersey City. Measurements of total Cr and Cr+6 in soil had been made previously by the NJDEP to identify COPR waste sites and the presence of chromate residue had been noted on the outside and the inside of some structures in Jersey City. However, no information was available at the time about residential exposure or about the relationship between the location of COPR waste sites and the potential for Cr+6 exposure. This first foray into assessing exposure to chromate production waste occurred as an outgrowth of the then, still new concept of microenvironmental exposure analysis.12 The first objective was to identify microenvironments presenting opportunities for Cr+6 exposure in residential settings. This was investigated through measurement of indoor air, outdoor air and house dust.

For the Lioy et al.11 study, COPR sites with a high potential for residential exposure were selected using site-specific data obtained from samples generated by the NJDEP for the purpose of identifying COPR sites. This study was based on a “purposive” exposure assessment approach13 in which subject selection is not random but targeted to a specific population of interest in order to better define its exposure. This approach differs fundamentally from the more common practice of survey sampling in that it does not attempt to describe the distribution of exposure within either the total population or the total exposed population. Consistent with this design, we selected four locations adjacent to or across the street from known COPR sites. Two to seven residences were sampled at each location (n = 19). In addition, following the same protocol, we sampled 11 comparison residences from two New Jersey communities with no known sources of Cr+6.

This was one of the first studies to use the LWW sampler14 that was developed to quantitatively and reproducibly sample accumulated dust on surfaces. The LWW sampler was used to collect dust samples from furniture, window sills, refrigerator tops and similar locations that are not cleaned frequently. The LWW sampler was a significant improvement over previous surface-dust sampling methods because it eliminated variability due to hand pressure, provided quantitative recovery of dust from smooth surfaces and sampled a reproducible area.15

We attempted to comprehensively characterize particle-bound Cr exposure in the residential environment in order to understand how living near a known COPR site presenting a high exposure potential might be associated with residential contact with the COPR material. Dust was sampled on surfaces with the LWW sampler and on floors with a small hand-held vacuum. PM10 (particulate matter having a diameter ≤ 10 μm) was sampled in indoor and outdoor air over 3–4 days. We also obtained information on heating, ventilation and non-environmental sources of Cr exposure, including occupational exposures. At the end of the sampling period, we collected data on cleaning and recreational activities that occurred during the study.

We found that for the Jersey City locations as a whole, both Cr dust loading (μg/cm2) and Cr concentration (p.p.m, μg-Cr/g dust) were significantly greater than at the comparison locations. Cr concentration was less variable than Cr loading. Indoor and outdoor concentrations of Cr in air were comparable in Jersey City and the comparison location. Indoor smoking appeared to make a major contribution to indoor Cr levels.

Lessons Learned from This Study

Households located on or near COPR contaminated sites had the potential for accumulating Cr associated with nearby sites.

With the possible exception of individuals who spent a significant fraction of their time outdoors and/or who had direct and frequent contact with waste sites, indoor locations likely accounted for the bulk of exposure to particulate-based contaminants that originated outdoors.

In household dust, Cr loading and concentration are not closely correlated and reflect different aspects of exposure. Loading reflects exposure potential as it is directly related to the mass of available material, while concentration is a signal for specific (i.e., non-background) sources. Loading is dependent on both concentration and total dust mass. Particularly when considering dust with a relatively unchanging combination of sources, concentration is essentially independent of dust mass.

At least for Cr contamination in Hudson County, outdoor ambient Cr air concentrations were not correlated with either loading or concentration in indoor dust. This result suggests that transport indoors and/or re-entrainment indoors are episodic events.

Floor vacuum samples do not reflect the same material that is available for exposure by wipe sampling on surfaces. Wipe sampling appears to provide a more sensitive indication of differences in exposure potential across household locations. This may be because, like all particles, the Cr-rich COPR particles are subject to re-suspension, thus resulting in their eventual deposition on elevated surfaces. Thus, wipe samples obtained from these surfaces reflect more active source of Cr particles than do floor vacuum samples.

“Residential Exposure to Chromium Waste—Urine Biological Monitoring in Conjunction with Environmental Exposure Monitoring”16

Given our findings in Lioy et al.11 that the residential microenvironments in homes near COPR sites with high exposure potential had higher levels of Cr in household dust, the next question was whether this increased exposure potential in the indoor environment was reflected in internal measures of exposure. To investigate the question, we combined the household Cr dust study design used in Lioy et al.11 with urine Cr biomonitoring of residents in the same homes.

The study population consisted of 50 residents in 17 homes at four locations in Hudson County (mostly in Jersey City) on or adjacent to known waste sites. The comparison population was 24 residents in 11 homes in two communities with no history of COPR contamination. We collected one-time (spot) urine samples from adults and children in these homes.

Before the Stern et al.16 study, Cr biomonitoring had mostly been used as a tool for occupational exposure assessment. In occupational settings with specific Cr exposures, urine concentrations are anticipated to be much higher than in residential settings—even those residential settings with significant environmental contamination. Historically, comparison of urine Cr concentrations in non-occupational settings had been limited by high laboratory-background contamination and by the confounding of Cr urine concentration by inter-individual variability in urine diluteness. In the 10–20 years before this study, with the recognition of the need for “clean” sampling and analytical procedures and with the introduction of laboratory methods such as Zeeman effect correction that minimized matrix interferences, estimates of normal urine Cr had decreased by 1–2 orders of magnitude.

In the biomonitoring portion of the study, when the study population was stratified on the basis of high (75th or 90th percentile) Cr dust loading in their homes, we observed that, with creatinine-based correction for urine diluteness, urine Cr levels in the residents of the Jersey City homes were significantly greater than those of the residents in the comparison locations.

Lessons Learned from This Study

The Cr levels in household dust are reflected in Cr concentrations in urine when examined on a population basis.

There is significant background variability in urine Cr from non specific sources. Measurement of Cr in household dust is also subject to sources of background variability from sources that are unrelated to nearby soil contamination. The sources of variability and uncertainty in exposure estimation that are inherent in each of these measures are different. Thus, when both urine Cr and household dust Cr are considered together, a more precise picture of exposure emerges than could be achieved with either measure alone.

Cr levels in household dust can be used as an effective discriminator variable for urine Cr based on identifying those exposed to a specific source.

Accounting for urine diluteness through creatinine (or other) correction can be an important tool for increasing the specificity of population-based Cr urine biomonitoring.

In using population-based urine grab/spot sampling, it is necessary to avoid overcorrection due to over-dilute urines (i.e., low creatinine concentrations).

Despite known foods and beverages with elevated Cr levels, there does not appear to be any specific aspect of diet that significantly affects urine Cr levels. This is likely due to an easily saturated Cr+3 absorption capacity.

“Purposive” exposure assessment, such as in this study, is an important tool for drawing conclusions regarding exposure and particularly in focusing Cr biomonitoring results.13 Random (i.e., unbiased) subject selection in such cases can obscure important relationships in the exposed population subsets of true interest.

“Particle-Size Distributions of Chromium: Total and Hexavalent Chromium in Inspirable, Thoracic, and Respirable Soil Particles from Contaminated Sites in New Jersey”17

Given the potential for the transport of COPR into residences as well as the possibility of outdoor exposure through passive (wind-blown) and active (e.g., truck traffic on unpaved surfaces) processes, it was necessary to characterize the size distribution of the Cr in the COPR material. To this end, we collected and composited surficial samples from two known COPR sites, Liberty State Park and Kearny, NJ. At the latter site, the soil had yellow “chrome blooms,” a hallmark of COPR contamination1 produced by cycles of capillary movement of Cr+6-containing soil water to the surface followed by efflorescence (the evaporation of water from salt solutions).

Samples were manually sieved to <30 μm and then fractionated in a resuspension chamber. The sieved material was extracted with water and was also digested with several different acid extractions (nitric, sulfuric or hydrofluoric) to investigate the potential availability of the Cr in the COPR material after inhalation or ingestion into the body.

As expected, given the naturally occurring in situ extraction process that resulted in the Cr+6 blooms, the Cr+6 concentration in the chrome blooms was much higher than in the bulk COPR soil. Although total Cr was somewhat enriched in the 10–30-μm size fraction, both total Cr and Cr+6 were found throughout the size fractions, including PM2.5 (particulate matter having a diameter ≤ 2.5 μm). Cr+6 in the bloom material varied by less than a factor of two between total suspended particulate and PM2.5. Thus, the Cr+6 in the COPR material would be available for deposition in the lower reaches of the respiratory tract and a reasonable estimate of the concentration of Cr+6 in the particles that could be retained in the respiratory tract could be obtained from the concentration in the total suspended particulate. Another important finding was that a significant fraction of the total Cr was refractory to nitric or sulfuric acid extraction, but was liberated by hydrofluoric acid. Thus, although this refractory portion might not be biologically available with ingestion exposure, with inhalation exposure and long-term retention of small particles in the lower respiratory tract, continuous, low-level extraction of this material could result in toxicologically significant chronic exposure.

Lessons Learned from This Study

When considering the inhalation exposure potential of contaminated soil, it is important to address the contaminant profile in the toxicologically relevant size fraction.

Cr+6-containing particles in the COPR were easily resuspend able by wind or vehicle traffic.

A significant amount of the particle Cr was refractory to all but the most aggressive acid extraction. This implied that standard extraction would not yield the total Cr content. To the extent that particles were retained long term in the respiratory tract, refractory Cr+6 in refractory material could pose a greater cancer risk than readily extractable Cr+ as it would result in more continuous exposure due to long-term leaching by lung fluid.6,7

The “blooms” were highly enriched in Cr+6 and although Cr+6 was not enriched in the smallest size fractions it was well represented in those fractions. Therefore, the bloom material posed a significant Cr+6 exposure potential.

“The Effect of Remediation of Chromium Waste Sites on Chromium Levels in Urine of Children Living in the Surrounding Neighborhood”18

As originally designed, the purpose of this study was to follow up on the relationship between Cr in household dust and Cr in residents’ urine observed in our earlier study16 by focusing specifically on children. In addition, we investigated the relationships between children's outdoor activity in areas near COPR sites and their Cr+6 exposure as reflected in urine Cr concentration. The study focused on a specific residential neighborhood adjacent to multiple COPR sites that was found in our earlier study11 to have significantly elevated household dust Cr loading relative to comparison locations. As children's outdoor activity varies seasonally, we designed the study to compare Cr exposure metrics in repeat sampling of children and their homes. The house dust data were from three rounds of dust sampling from these homes: our earlier study in summer 1990;11 and two samples obtained from the same homes during this study (summer 1991 and fall 1991). Spot urine samples were obtained from the same children in summer and fall 1991. Serendipitously, remediation of the surrounding COPR sites was carried out after the initial summer 1990 study.11 This provided a unique opportunity for us to ask the question: Did elimination of the presumed source of the elevated Cr in the house dust lead to reduction of Cr in indoor dust and urine?

In addition, given the potential for inter-individual variability in urine diluteness to decrease the utility of population-based urine biomonitoring for Cr exposure,16 we investigated the use of creatinine correction and specific gravity as methods to compensate for this variability.

In the initial 1990 study in this Jersey City neighborhood,11 we found that the Cr dust loading was 2–14 times higher than in the comparison (non-Jersey City) homes. However, in the two follow-up (post-remediation) samples in the same homes, the Cr loading had declined by 68% in the first follow-up sample and by 89% by the second follow-up. Cr concentration similarly declined by 16% and 69%. Furthermore, in the follow-up study, there was no significant difference in loading compared with the comparison homes. The observed decline in Cr dust levels was thus temporally associated with the remediation of the surrounding sites that involved removal of the contaminated soil from each residential location. Consistent with the decline in household dust Cr levels, children's urine Cr was no longer correlated with household dust measures.

The post-remediation urine Cr levels were highly correlated between summer and fall samples. With the elimination of all or most of Cr contribution from COPR, the seasonal consistency in urine Cr showed that population-based urine biomonitoring for Cr was reproducible despite the underlying intra-individual variability in diet and other background sources of Cr exposure and despite temporal variability in urine diluteness. This observation provided additional validation of the use of urine Cr to assess population-based environmental exposure around the waste sites. Interestingly, the correlation between the fall and summer urine Cr results was strongest for uncorrected or specific-gravity-corrected concentrations but considerably weaker for creatinine-corrected values. This probably stemmed from age-dependent differences in creatinine-clearance rates and points to the importance of investigating multiple measures of urine biomarker concentration. Finally, despite the fact that the children at the Jersey City location spent more time outside than children in the comparison locations, there was no clear difference in urine Cr levels. This further supports the effectiveness of the waste-site remediation.

Lessons Learned from This Study

Removal of the COPR waste was effective in reducing the potential for residential contact with Cr in homes adjacent to waste sites.

Household dust Cr levels appear to be responsive over the course of 1 year to elimination of significant outdoor sources of Cr.

Despite several potential sources of intra-individual variability, urine Cr biomonitoring with spot/grab samples can provide a consistent measure of population-based exposure.

Correction for urine diluteness (creatinine or specific gravity) can be of value in biomonitoring for Cr. However, its utility is not necessarily predictable a priori in a given study. In this study, for example, the uncorrected urine Cr concentration gave the strongest correlation between summer and fall samples from the same individuals.

Pre- and post-remediation analyses are essential for verifying the success of remediation efforts in reducing exposure.19

“Community Exposure and Medical Screening near Chromium Waste Sites in New Jersey”20

The initial information on the scope of Cr contamination and residential exposure raised sufficient concern about exposure that the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services (NJDHSS) sponsored a Chromium Medical Surveillance Program (CMSP). During 1992–93, screening was offered to residents in 14 neighborhoods and workers in 78 workplaces identified as being on or near COPR sites. The final report was published by the NJDHSS in 1994.

The goals of the CMSP were (1) to provide both clinical screening and laboratory analysis to resident and worker populations and (2) to provide the State of New Jersey with a public health basis for decision-making about remedial actions. The screening included a physical examination for dermal irritant or allergic effects and measurement of urine chromium concentration as a measure of recent exposure. Individuals with lesions possibly attributable to Cr exposure or with elevated urinary Cr were referred for further evaluation. Of the 806 residents and 938 workers, 32 adults were referred for follow-up evaluation based on physical findings, and 158 adults and children were referred for urine levels >0.5μg/l. The proportion of persons referred on the basis of the urine chromium test varied among the screened groups. Multiple linear regression models showed that average urine chromium differences between residents and a comparison group, adjusting for potential confounders, were highest in children <6 years of age. Of the 32 persons who were referred for further clinical evaluation, chromium was determined to be a likely cause of lesions in 6 (18%). The screening results indicated the need for expanded environmental evaluation in specific residential areas and workplaces.

The urine Cr concentrations (Cr-U) of the 1712 potentially exposed persons (within two city blocks of a known COPR site) were compared with 315 non-exposed individuals, from other parts of Jersey City. For children 1–5-years old, the 90th percentile of urine Cr was 1.14 μg/l versus 0.46 μg/l. Multiple regression models accounting for confounders and urine diluteness found significantly higher urine chromium in children <6-years old in the chromium-exposed neighborhoods compared with the reference children. This was consistent with earlier studies comparing urine Cr with chromium in household dust.16

Lessons Learned from This Study

Consistent with what had been observed previously on a smaller scale, urine Cr biomonitoring is capable of detecting population-based differences in exposure above the “noise” of inter- and intra-individual variability in Cr toxicokinetics.

Children are a more sensitive population for detecting exposure to Cr in house dust. This is likely the result of their greater vulnerability to uptake of contaminants in household dust through hand-to-mouth behavior.21 This vulnerability is well-documented in the case of lead exposure in toddlers.22

“Exposure to Chromium Dust from Homes in a Chromium Surveillance Project”23

We had demonstrated the positive association of Cr in house dust and internal measures of exposure (i.e., urine Cr) in the presence of an ongoing source of COPR exposure in Stern et al.16 and the lack of association of these metrics in the absence of an ongoing source (following site remediation) in Freeman et al.18 Those associations, however, were based on a relatively small sample size. The large amount of biomonitoring data that was anticipated to be collected in the CMSP provided a unique opportunity to refine our knowledge about the relationship between these external and internal metrics of exposure. We therefore took advantage of the structure of the CMSP to conduct household dust sampling and administer exposure questionnaires in a sample of the households of individuals who were examined in the CMSP. Houses were included if at least one person in the household was screened in the CMSP. A total of 220 homes with CMSP participants was included and 47 comparison homes outside Hudson County were similarly studied. Although all of the Hudson County homes were selected on the basis of a resident's participation in the CMSP, house selection and sampling were conducted blind to the “referral status” (i.e., the dichotomous characterization of urine Cr level of the CMSP participants—see above for a more detailed description of “referral status”).

The sampled homes were located in eight distinct neighborhoods. The neighborhoods differed both geographically and with respect to the density of nearby COPR waste sites. In contrast to our earlier studies that were designed as focused investigations of one or, at most, a few neighborhoods, the design of this study allowed us to investigate the variability of household dust measures of Cr exposure across different neighborhoods. COPR waste sites occurred throughout large areas of Hudson County and particularly, Jersey City. Thus, it was not known whether exposure to Cr from COPR occurred more or less uniformly throughout the area or varied by neighborhood depending on various factors, including the character and density of the nearby waste sites. In addition to homes identified in the CMSP as being within the catchment of a known COPR site(s), the study also included 21 homes located in proximity to, but not within, a catchment area, and 20 homes in Jersey City that were not associated with any of the catchment areas. These homes allowed us to better define the variability in the association between house dust Cr measures and proximity to COPR waste sites. Because it was not clear that any area of Jersey City could a priori be considered to be free of the potential for exposure to COPR, we selected comparison homes in communities outside of Hudson County from among the comparison homes in the CMSP and supplemented those with additional homes from other non-Hudson county locations. Finally, the large number of homes in this study allowed us to investigate household practices that influenced measures of Cr in house dust.

For both Cr concentration and Cr loading, the Hudson County homes had levels about twice those in the comparison homes in Jersey City (i.e., not located in proximity to known waste sites) as well as the comparison homes outside Hudson County. There was significant variability among the catchment areas in both concentration and loading. Compared with the group of comparison homes, 63% of the catchment areas had significantly greater Cr dust concentration and 50% had significantly greater Cr dust loading. This precluded the notion that homes throughout Hudson County or Jersey City were all similarly subject to COPR waste exposure. However, homes located “adjacent” to catchment areas were also significantly elevated in concentration and loading compared with the comparison houses. For the houses not associated with catchment areas, loading and concentration were also elevated compared with the comparison houses. Thus, although COPR exposure was not ubiquitous in Hudson County or Jersey City, neither did it appear to be confined strictly to the immediate vicinity of waste sites.

In contrast to our findings in Stern et al.,16 we did not find associations between elevated urine Cr concentration (as reflected in a positive referral status in the CMSP) and either Cr dust concentration or loading in this study. At the time of this study, the urine data from the CMSP study were only available in dichotomous form (referral/non-referral). In investigating associations between urine Cr and dust Cr, the use of dichotomized urine data necessitated, in turn, the dichotomization of the Cr dust data. It is likely that the use of dichotomous data weakened our ability to detect underlying relationships between these inherently continuous variables. This was subsequently addressed in Stern et al.24 (below).

We found that Cr loading was significantly lower in homes where house cleaning had occurred within 1 week before sampling. House cleaning also appeared to be associated with a reduced exposure to Cr. Residents were more likely to have a non-referral status for urine Cr (i.e., a lower urine Cr concentration) if their home was recently cleaned. Interestingly, the presence of a doormat was also associated with a non-referral status. The result suggested that Cr-containing particles tracked in to the home significantly contributed to exposure.

Lessons Learned from This Study

Dust concentration and loading are effective measures for distinguishing among locations with respect to their potential for residential exposure to a dust-borne contaminant.

Although dichotomous measures of exposure are useful for screening, they can pose important limitations when investigating associations.

Dust sampling in areas of the house that are not normally cleaned can, nonetheless, provide an indication of dust levels throughout the house.

Tracking in of contaminants on shoes (as reflected by the effectiveness of doormats in reducing dust levels) could have been a significant source of contaminant transfer into homes and can be a source at other locations.

“The Association of Chromium in Household Dust with Urinary Chromium in Residences Adjacent to Chromate Production Waste Sites”24

Given our findings in previous Hudson County chromium studies that urine Cr concentrations and household dust measures of Cr exposure were significantly associated, we were surprised to find that the results from Freeman et al.23 failed to show such associations. In Freeman et al.,23 the sample size was larger than in our previous studies and thus that study might have been expected to be even more likely to reveal such an association. Nonetheless, we suspected that our inability to observe such an association resulted from the restrictions on statistical power posed by a dichotomous urine Cr measure (referred/non-referred) and the necessity of pairing that variable with a similarly dichotomous measures of Cr in house dust. Both the urine Cr data and the house dust Cr data were initially generated as continuous variables. For the purposes of medical screening in the CMSP, however, the continuous urine Cr concentration data were transformed into a dichotomized variable. We thus obtained the raw CMSP urine data, including Cr concentration, creatinine concentration and specific gravity, and combined these data with our original continuous measures of Cr concentration and loading in house dust.23 We also obtained demographic information for each CMSP participant (n = 329) whose house was sampled for dust in the Freeman et al.23 study (n 220). This approach allowed us to investigate models that simultaneously addressed multiple determinants of urine Cr, potentially including measures of urine diluteness, age and household dust Cr measures.

We found a significant bivariate relationship between urine Cr concentration and house dust Cr concentration for the entire population (Figure 2a). This relationship was stronger when we looked only at those ≤ 10-years old (Figure 2b). There also appeared to be a relationship between urine Cr and Cr dust loading in that group, albeit of borderline statistical significance. Consistent with our observations in Freeman et al.,18 the strongest association was obtained with uncorrected urine Cr concentration. Despite the fact that variability in urine diluteness increases inter-and intra-individual variability in urine Cr concentration, adjusting the urine Cr concentration by creatinine or specific gravity did not increase the strength of the association. When we examined the population < 10-years old, we found no relationship between urine and dust Cr measures (Figure 2c). Thus, the relationship we observed between Cr dust concentration and urine Cr concentration in the full sample was attributable to exposure of children but not adults. The dust–urine exposure relationship in children became even clearer in our best-fitting multiple regression model of urine Cr. Within the stratum of ≤ 10-years old, age, Cr dust concentration and creatinine urine concentration (as a separate variable from urine Cr concentration) were all highly significant independent variables. Age was negatively associated and Cr dust concentration positively associated with urine Cr concentration. No house dust Cr measure was significantly associated with the urine Cr concentration for those > 10-years old.

Figure 2.

(a–c) Relationship between the logarithm of urinary chromium concentration and chromium concentration in house dust in homes in Jersey City, New Jersey. Reproduced by the permission of Environmental Health Perspectives. From Stern et al.24 reprinted with permission of Environmental Health Perspectives.

This study not only confirmed our earlier findings in Stern et al.16 of an association between the urine Cr biomarker of exposure and the household dust Cr environmental measure of exposure but, consistent with the findings in the CMSP study,20 also showed that the relationship was due to children and that younger children's urine Cr concentrations were associated with their household dust exposure. The result is what would have been expected based on observations of children's hand-to-mouth behavior25 and their greater access to soil, floors and other dusty surfaces. Further, this observation is consistent with the observation of the increased exposure of young children to pesticides21 and lead.26

We had previously shown that both house dust Cr measures and urine Cr were associated with living near unremediated COPR waste sites. However, each of these measures carries its own inherent imprecision as a predictor of exposure. House dust Cr is a valid measure of Cr in the residential environment, but it is an external (i.e., potential) measure of exposure and thus one step removed from internal exposure. Urine Cr is a direct measure of internal exposure, but it is potentially confounded by non-environmental (i.e., dietary) Cr exposures and by inter- and intra-individual variability in urine diluteness. This study demonstrated that by simultaneously applying both types of measures to the same population, a more focused picture of exposure can be obtained.

Consistent with our previous observations, this study found that while urine diluteness can be a source of uncertainty in the use of urine Cr as a measure of exposure, there is no a priori best method for adjusting for dilution. The best strategy is to collect both creatinine and specific gravity data and to investigate their utility (or lack of utility) through statistical analysis of the data using models that account for multiple predictors of urine Cr, particularly age.

Lessons Learned from This Study

The predictive value of dust sampling (an external measure of exposure) and urine sampling (an internal measure of exposure) is each increased when both measures are combined. This is because each measure has different sources of imprecision in predicting exposure.

The elevated exposure of children (as opposed to adolescents and adults) to Cr in house dust is consistent with what has been observed for pesticides and lead.

The concentration of chromium in any spot urine sample is subject to variation from, at least, intake, elimination kinetics and urine diluteness. This has the potential to result in both inter- and intra-individual variability. There is not necessarily an a priori best method to reduce the variability in the concentration of a urinary biomarker, and such adjustments are best investigated within an overall regression model.

Continuous biomarker data (such as that utilized in this study) are a more appropriate measure of exposure than a dichotomous reduction of those data (such as referral status), which is often subject to arbitrary cutpoints. Although this is obvious from a statistical standpoint, the frequent use of dichotomous biomarker data in exposure studies makes this lesson worthy of repetition.

“Reduction in Residential Chromium Following Site Remediation”27 In Freeman et al.,18 our return to a neighborhood after the adjacent COPR sites had been remediated serendipitously provided an opportunity to observe the effect of site remediation on our measures of Cr exposure potential. However, that study focused on a single neighborhood and incorporated a limited follow up. Hazardous site remediation is the goal that drives a large amount of the environmental efforts that continue to be undertaken by environmental agencies on the state and federal levels. Nonetheless, it is rare that the site remediation efforts are evaluated for their effectiveness in reducing exposure to the contaminants of concern. Thus, the continuing COPR site remediation in Jersey City provided a unique opportunity to determine whether these efforts were, in fact, successful in reducing residential exposure to Cr and to understand the time frame over which such exposure reductions might occur.

Drawing on the pre/post-remediation sampling strategy that we used in Freeman et al.,18 we expanded the scope of that study to three different neighborhoods and extended the length of post-remediation follow-up in each home to four visits over the course of approximately 2 years. The initial sample in each house was collected in 1992–93. Remediation of all the surrounding COPR sites in each of the three neighborhoods had been completed before the first follow-up samples in this study at the end of 1996.

Because the concentration of a contaminant in house dust is a better maker for a source of that contamination than loading, which is more subject to influence by overall dustiness, we relied on concentration to determine whether site remediations had eliminated COPR as a source of Cr in house dust. Based on Cr dust concentrations measured in each house in the initial (pre-remediation) sample, we characterized each house as having either low, medium or high Cr dust concentration. Table 1 shows the Cr dust concentrations over the course of the sampling visits in each of the initial concentration categories. Homes that were initially in the high or medium category showed a steep decline in Cr concentration between the initial sample and all subsequent samples (Table 1). Homes with low Cr concentration continued to have a low concentration after remediation and following the decline, all categories maintained levels that were consistent with background.

Table 1.

Comparison of chromium concentrations (μg/g) in houses by initial chromium category.

| Category | Initial Cr | Visit 1 | Visit 2 | Visit 3 | Visit 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | |||||

| Mean ± s.d. | 58 ± 33 | 53 ± 61 | 61 ± 61 | 85 ± 53 | 54 ± 106 |

| Median | 48 | 30 | 49 | 105 | 1 |

| n | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Medium | |||||

| Mean ± s.d. | 248 ± 76 | 67 ± 58a | 49 ± 78a | 48 ± 34a | 66 ± 77a |

| Median | 245 | 47 | 21 | 45 | 34 |

| n | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| High | |||||

| Mean ± s.d. | 782 ± 331 | 97 ± 103a | 35 ± 27a | 78 ± 135a | 55 ± 60a |

| Median | 739 | 75 | 39 | 16 | 50 |

| n | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| P < 0.001b | nsc | nsc | nsc | nsc |

Significantly less than initial Cr concentration (P < 0.01) (Friedman and Wilocoxon analyses of variance).

Significant difference across categories (Mann–Whitney test).

No significant difference across categories.

From Freeman et al.27 Reproduced by permission of the Journal of the Air and Waste Management Association.

These findings were strongly consistent with a decline and return to background associated with the remediation resulting from the complete removal of the COPR from these locations. The remediation efforts appear to have been highly successful in reducing the Cr concentration in the dust in the homes adjacent to the contaminated sites. Relative to the time course of this study, the reduction occurred rapidly, within 1 year. This is consistent with the decline to background within a year seen in our earlier Freeman et al.18 study. Finally, the dramatic reduction in house dust Cr concentration associated with the remediation of the nearby COPR sites provided a strong validation of our earlier conclusions linking the presence of nearby sites to the measures of Cr in house dust.

Lessons Learned from This Study

Remediation of adjacent contaminated sites by removal of the contaminated soil is effective in reducing in-home exposure to particulate-bound Cr.

Reduction of in-home exposure potential is rapid—probably occurring over the course of ≤ 1 year.

Repeat sampling of household dust (under constant environ mental conditions) gives stable and consistent results.

“Hexavalent Chromium in House Dust—A Comparison Between an Area with Historic Contamination from Chromate Production and Background Locations”28

By the time that this study was initiated (2006), nearly all of the COPR sites in Jersey City had undergone excavation and removal of COPR material, permanent capping or, for a few large-scale sites, interim capping. Nonetheless, the community remained concerned about the potential for continued exposure resulting either from incomplete remediation of known sites or from the existence of unknown sites. The Stern et al.28 study was undertaken to address these concerns.

At this point in the history of our chromium exposure studies, the analytical laboratory methodology had evolved to make it feasible to quantify Cr+6 in wipe samples of house dust rather than relying on total Cr as in our previous studies. Cr+6 tends to be unstable and to become reduced to Cr+3 in non-oxidizing environments. Furthermore, Cr+6 had generally been believed to occur largely as a result of specific anthropogenic processes except in very specific geological environments.29 Thus, our expectation on entering into this study was that Cr+6 would be found in house dust only if it originated from COPR or from some other specific source of Cr+6 release outside the homes. As we were not aware of any significant source of Cr+6 in Jersey City other than COPR, our hypothesis was that Cr+6 in house dust in Jersey City would be a signal for ongoing sources of COPR exposure. By the same logic, we did not expect to find Cr+6 in the house dust from the comparison locations selected for this study from communities with no known sources of Cr+6.

The design of this study was similar to that of our earlier house dust studies. Jersey City homes (n = 100) were located in five neighborhoods in close proximity to remediated or interim remediated COPR sites. These included neighborhoods in which we had detected elevated Cr in dust a decade earlier. Also included were individual homes in locations self-identified by residents but without a history of a nearby COPR site. We also sampled 20 comparison homes in communities distant from Jersey City without COPR or other known chromate sources. We selected three areas in each home, including a living area (usually bedroom), a window well and a basement surface for dust sampling using the LWW sampler. We sought surfaces where dust was likely to accumulate. We also collected data on household renovation, house age and observations on adjacent ground cover.

To our surprise, Cr+6 was detected in every home, including in all of the comparison homes. For pooled household data, there was no significant difference in Cr+6 dust concentration between the Jersey City and comparison homes (3.9 p.p.m and 4.6 p.p.m, respectively). For Cr+6 loading, the levels in the comparison homes were significantly greater than the Jersey City homes (10.0 μg/m2 and 5.8 μg/m2, respectively). Within Jersey City, there were significant differences in Cr+6 concentration among the neighborhoods but with a maximum mean difference of a factor of three. The Jersey City neighborhood with the largest mean pooled household concentration exceeded the mean concentration in the comparison homes by a factor of 1.5. When we stratified the analysis on the basis of surface type and household location (wood/laminate surfaces in living areas; vinyl surfaces in window wells), there was no significant difference between Jersey City and the comparison locations for either concentration or loading. Thus, the study failed to find evidence of a Jersey City-specific source of Cr+6 in house dust but did find evidence of a pervasive Cr+6 presence in house dust that was not specific to Jersey City.

Interestingly, we observed lower dust Cr+6 concentrations in window-well samples compared with other, strictly indoor surfaces. Thus, it does not appear that outdoor sources were the major contributors to the Cr+6 in house dust. A possible clue to the source of the ubiquitous presence of Cr+6 in house dust in this study was that all samples with Cr+6 concentrations designated as “high” (>20 p.p.m.)—6 in Jersey City, 1 in a background home—were each found on single stained wooden surfaces in individual homes. This may be related to wood stains that were known to commonly contain Cr+6 in the period 1910–70.30 This is also consistent with our observation that in Jersey City, Cr+6 dust concentration was significantly correlated with the age of the house. We also found some intriguing associations with various aspects of adjacent ground cover, but the variability in ground cover was insufficient to draw firm conclusions about the possible contribution of soil or soil amendments.

Thus, given our finding that Cr+6 in household dust at concentrations < 10 p.p.m. appeared to be ubiquitous in the Jersey City and comparison areas sampled in this study, and given the apparent association of “high” (420 p.p.m.) levels with indoor stained wood surfaces, Cr+6 house dust found in this study appears to be due, at least in part, to indoor sources. However, it is important to keep in mind that these findings are specific to the recent time frame (2006 and forward) within which this study was conducted. Between the initiation of our earliest studies in Jersey City and this study, a great deal of remediation occurred. As a likely result of this remediation, the results of Stern et al.28 appear to reflect the background of Cr+6 in house dust in general rather than conditions in Jersey City attributable to COPR. This is in marked contrast to the conditions we documented in our initial studies.

Allergic contact dermatitis due to Cr+6 is one of the most common allergic dermatoses. It is notable for its persistence in affected individuals.5 The apparent ubiquitous occurrence of Cr+6 in house dust may provide a clue to this persistence.

Lessons Learned from This Study

It is feasible to focus dust sampling studies specifically on Cr+6. This reduces the background “noise” from Cr+3 that can occur when total Cr is used as a surrogate for Cr+6.

There was no evidence of ongoing sources of household exposure specific to Jersey City. With the final remediation of nearly all residential COPR waste sites, Cr+6 in house dust in Jersey City is not statistically distinguishable from the general background in other locations.

Nonetheless, Cr+6 appears to be ubiquitous in house dust. The role of ambient sources (especially air) is not known, but much of the indoor Cr+6 appears to originate indoors.

Cr+6 in household dust may have implications for the clinical persistence of Cr+6 allergic contact dermatitis.

DISCUSSION

The chromium exposure studies in Jersey City discussed in this review can be viewed from two perspectives. The first is the perspective of the development of exposure science and how our studies of COPR exposure both paralleled, and, to a large extent, drove the development of some important concepts in exposure science. The second is the specific contribution of these studies to the understanding of Cr exposure in Hudson County/Jersey City, New Jersey, and the utility of these studies in defining the scope and importance of decisions by regulatory and judicial agencies.

From the first perspective, these studies were among the first to specifically use household dust as a measure of (external) exposure. This is particularly important because although off-site groundwater contamination was long recognized as a route of exposure from waste sites, exposure to soil-bound contaminants was generally addressed by sampling of soil cores on-site. Such an approach expressed a narrow understanding of exposure that tended to focus mainly on exposure on the site and to interdict the route of exposure to soil-bound contaminants by restricting access to the site.31 In our studies, we demonstrated that the soil-derived accumulation of chromium in household dust presented an important pathway of exposure to nearby waste sites even for those who never set foot on the sites. In addition, because inhalation exposure to soil-bound particles occurred off-site due to episodic re-suspension of particulates in household dust, air monitoring was not necessarily the best method by which to assess the potential for inhalation exposure. Furthermore, air monitoring was not a good method to assess the potential for ingestion of dust. To meet this need, we developed methods such as quantitative dust sampling using the LWW sampler that were capable of reproducible sampling of household dust—a proximate source for both inhalation and ingestion of dust. Using this approach, we were able to define the spatial and, ultimately, the temporal relationship between the waste sites and household exposure to Cr originating on those waste sites. In large part, due to the relationships and methods developed in these studies, household dust sampling has matured into an accessible and important tool in identifying and quantifying the exposure potential presented by waste sites and environmental contamination in general.31

Household dust sampling is a tool for characterizing the household microenvironment. In terms of time budgets of exposure, the home is a critical microenvironment—especially for children.31 Nonetheless, dust sampling is a measure of external exposure, which is to say, potential exposure. External exposure is defined as the concentration of a contaminant at the point of contact with the contaminant.32 For air, the link between this contact and internal exposure is tight. However, for dust (and soil) ingestion, the link is less tight and is governed by behaviors that result in contact such as mouthing behavior and hand-to-mouth contact. Thus, for understanding the exposure to contaminants in household dust, microenvironmental measurement cannot fully predict internal exposure.15 Following the very early example of lead, these studies were among the first to bridge the gap between measurement of external and internal exposure for other environmental contaminants by showing the association between Cr in household dust and Cr in urine. In particular, the demonstration that household dust Cr was strongly associated with urine Cr in children established the bridge between external and internal exposure to waste-site Cr in this environment. Although internal exposure is necessary for establishing a link to toxicological effects and dose response, it is less useful for understanding the etiology of exposure. By contrast, external exposure is a weaker predictor of dose but is well suited for investigating the sources of exposure.15 Thus, in the context of environmental science, the bridge between these measures of exposure is critical to understanding the full picture of exposure but is still not commonly investigated in exposure studies.15

From the more specific perspective of Hudson County/Jersey City, these studies were important in elevating the perception of the COPR exposure from an in-situ and site-specific perspective to one of off-site and household exposure. The major COPR sites that were located on, or immediately adjacent to, the chromate production facilities were known from the outset. Other sites were identified through the efforts of the state and local governments by diligent record searches and shoe-leather field surveys. The identification of these sites lead to engineering-based remediation efforts focused on the sites, themselves. Although specific instances of Cr+6 migration off-site through runoff and subsurface hydrologic transport were noted,1 the off-site impact of these sites from particulate transport was not anticipated before the studies in this review. The understanding that these sites had the widespread potential to contaminate nearby residences had a major role in transforming the perception of this contamination from a strictly waste-site issue to a neighborhood and community concern. This, in turn, had a role in empowering the residents to pursue legal remedies to site remediation when regulatory efforts of many years duration ultimately became bogged down.

These studies were also successful in closing the loop connecting discovery and remediation by verifying the success of the remediation efforts in Hudson County/Jersey City. Although it is a standard practice in Superfund and similarly designed site cleanups to test the post-remediation soil on-site to ascertain compliance with cleanup limits, it is still rare that these efforts are investigated post-remediation to ascertain that they were successful in eliminating off-site impacts.19 Failure to reduce off-site exposures may indicate that remediation efforts on site were not successful and/or that other, hitherto unknown sources of contamination are present at other nearby locations. We were lucky to have both fortuitous timing and the support of the NJDEP in being able to sample dust in houses known to be impacted by nearby waste sites both before and several times after remediation of those sites. These studies showed that not only were the remediation efforts successful in dramatically reducing Cr levels in the dust over a short period of time but that the post-remediation Cr levels remained at background levels. With the awareness of off-site household exposures that has evolved from these studies, it is important to consider such follow-up studies when off-site exposure has been identified or can reasonably be expected.

Finally, these studies brought to light the surprising finding that Cr+6 appears to be pervasive in household dust. This suggests an ongoing low-level dermal exposure to Cr+6 and raises the interesting possibility that such ongoing exposure contributes to the particularly persistent nature of chromate allergic contact dermatitis.5

CONCLUSION

Our studies of COPR exposure in Hudson County constitute one important chapter in the development of exposure science for the assessment of the impact of hazardous waste sites on communities. In addition to addressing the specific problem of chromium contamination and exposure in Jersey City, these studies established and/or significantly contributed to the development of the following key exposure science concepts:

The systematic and symbiotic integration of exposure data and site remediation to assist in guiding cleanup policies and to provide assurance of progress and completion to concerned stakeholders.

The coordinated use of biomonitoring and microenvironmental sampling (i.e., internal and external markers of exposure, respectively) to close the gap between external and internal exposure assessment.

The importance of providing multiple and mutually reinforcing tools to stakeholders and risk managers to identify hazards and appropriate solutions that can be applied to multiple kinds of contaminants and settings when complex and controversial exposure and risk issues arise.

We strongly recommend that environmental and public health agencies evaluate sites relative to their potential for off-site exposure and apply these tools in cases with significant potential as appropriate. This approach is especially important when contamination is widespread and/or a large population is potentially exposed. In such cases, the use of these tools should be considered in order to define the goals of the remediation in terms of identifying, characterizing and then reducing the exposure to the off-site as well as on-site population. Importantly, these tools can be used in a demonstrable and quantifiable manner that can provide both clarity and closure to concerned stakeholders.

HIGHLIGHTS.

In this article we:

Review our studies of exposure to chromate production waste over two decades.

Discuss how these studies have advanced exposure science.

Show how the approaches developed are useful for characterizing and reducing exposure and providing clarity and closure for stakeholders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research discussed in this manuscript is derived from a number of research projects that started in the early 1990s, with the most recent projects funded by the NJ DEP, contract no. SR06-027 for Phase I, and contract no. SR08-016 for Phase II. In addition, PJL and MG are funded under the NIEHS CEED, 2P30ES005022-21780309. We also wish to thank the many community residents and members of the municipal government who assisted us throughout this 20-year effort. Finally, we wish to dedicate this work to Dr. Natalie Freeman who passed away in 2010. It was her insights on the behavior and activities of the residents that made the major conclusions much more plausible and reduced uncertainties in post-study remediation activities. Funding: The series of studies described in this review were supported by contracts with the State of New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CMSP

Chromium Medical Surveillance Program

- COPR

chromium ore-processing residue

- EOHSI

The Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute

- NJDEP

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DISCLAIMER

This paper does not necessarily reflect the policies of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burke T, Fagliano J, Goldoft M, Hazen RE, Iglewicz R, McKee T. Chromite ore processing residue in Hudson County, New Jersey. Environ Health Perspect. 1991;92:131–137. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9192131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gochfeld M. Setting the research agenda for chromium risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 1991;922:7–13. doi: 10.1289/ehp.91923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.USEPA. Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) 2010 accessed at: http://www.epa.gov/ncea/iris/subst/0144.htm11/4/2010.

- 4.Stern AH. A quantitative assessment of the carcinogenicity of hexavalent chromium by the oral route and its relevance to human exposure. Environ Res. 2010;110:798–807. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern AH, Bagdon RE, Hazen RE, Marzulli FN. Risk assessment of the allergic dermatitis potential of environmental exposure to hexavalent chromium. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1993;40:613–641. doi: 10.1080/15287399309531822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes AL, Wise SS, Sandwick SJ, Wise Sr JP. The clastogenic effects of chronic exposure to particulate and soluble Cr(VI) in human lung cells. Mutat Res. 2006;610:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langård S. Role of chemical species and exposure characteristics in cancer among persons occupationally exposed to chromium compounds. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1993;19(Suppl 1):81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.USPHS (US Public Health Service) In: Health of workers in chromate producing industry. Gafafer WM, editor. U.S. Public Health Service; Washington, D.C.: 1953. Pub No 192. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartlett RJ. Chromium cycling in soils and water: links, gaps, and methods. Environ Health Perspect. 1991;92:17–24. doi: 10.1289/ehp.919217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz SA. The analytical biochemistry of chromium. Environ Health Perspect. 1991;29:13–17. doi: 10.1289/ehp.919213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lioy PJ, Freeman NC, Wainman T, Stern AH, Boesch R, Howell T, et al. Microenvironmental analysis of residential exposure to chromium-laden wastes in and around New Jersey homes. Risk Anal. 1992;12:287–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1992.tb00676.x. Erratum in: Risk Anal 12: 463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lioy PJ. The analysis of total human exposure for exposure assessment: a multi-discipline science for examining human contact with contaminants. Environ Sci Technol. 1990;24:938–945. [Google Scholar]

- 13.NRC (National Research Council) Human exposure assessment for airborne pollutants: advances and opportunities. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lioy PJ, Wainman T, Weisel C. A wipe sampler for the quantitative measurement of dust on smooth surfaces: laboratory performance studies. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1993;3:315–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lioy PJ. Exposure science: a view of the past and milestones for the future. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1081–1090. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stern AH, Freeman NC, Pleban P, Boesch RR, Wainman T, Howell T, et al. Residential exposure to chromium waste—urine biological monitoring in conjunction with environmental exposure monitoring. Environ Res. 1992;58:147–162. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(05)80211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitsa V, Lioy PJ, Chow JC, Watson JG, Shupack S, Howell T, et al. Particle-size distribution of chromium: total and hexavalent chromium in inspirable, thoracic, and respirable soil particles from contaminated sites in New Jersey. Aerosol Sci Technol. 1992;17:213–229. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman NC, Wainman T, Lioy PJ, Stern AH, Shupack SI. The effect of remediation of chromium waste sites on chromium levels in urine of children living in the surrounding neighborhood. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 1995;45:604–614. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1995.10467390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lioy PJ, Burke T. Superfund: Is it safe to go home? J Expos Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2010;20:113–114. doi: 10.1038/jes.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagliano JA, Savrin J, Udasin II, Gochfeld M. Community exposure and medical screening near chromium waste sites in New Jersey. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1997;26:S13–S22. doi: 10.1006/rtph.1997.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman NC, Hore P, Black K, Jimenez M, Sheldon L, Tulve N, et al. Contributions of children's activities to pesticide hand loadings following residential pesticide application. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2005;15:81–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhoads GG, Ettinger AS, Weisel CP, Buckley TJ, Goldman KD, Adgate J, et al. The effect of dust lead control on blood lead in toddlers: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 1999;103:551–555. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeman NC, Stern AH, Lioy PJ. Exposure to chromium dust from homes in a Chromium Surveillance Project. Arch Environ Health. 1997;52:213–219. doi: 10.1080/00039899709602889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stern AH, Fagliano JA, Savrin JE, Freeman NC, Lioy PJ. The association of chromium in household dust with urinary chromium in residences adjacent to chromate production waste sites. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;10:833–839. doi: 10.1289/ehp.106-1533240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed K, Jimenez M, Freeman NCG, Lioy PJ. Quantification of children's hand and mouthing activities through a videotaping methodology. J Expos Anal Environ Epidemiol. 1999;9:513–520. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanphear BP, Roughmann KJ. Pathways of lead exposure in urban children. Environ Res. 1997;74:67–73. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1997.3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman NC, Lioy PJ, Stern AH. Reduction in residential chromium following site remediation. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2000;50:948–953. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2000.10464132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stern AH, Yu CH, Black K, Lin L, Lioy PJ, Gochfeld M, et al. Hexavalent chromium in house dust—a comparison between an area with historic contamination from chromate production and background locations. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408:4993–4998. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry) [7 January 2011];Draft Toxicological Profile for Chromium. 2008 http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp7.pdf. [PubMed]

- 30.Ruetze M, Schmitt U, Noack D, Kruse S. Untersuchungen zur mOglichen Beteiligung chromathaltiger Holzbeizen an der Entstehung von Adenokarzinomen in der NaseHolz als Roh- und Werkstoffs. 1994;52:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lioy PJ, Freeman NCG, Millette JR. Dust: a metric for use in residential and building exposure assessment and source characterization. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:969–983. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ott WR, Steinemann AC, Wallace LA, editors. Exposure Analysis. CRC-Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2007. [Google Scholar]