Abstract

Islet Amyloid Polypeptide (IAPP) is a 37-residue hormone cosecreted with insulin by the β-cells of the pancreas. Amyloid fiber aggregation of IAPP has been correlated with the dysfunction and death of these cells in type II diabetics. The likely mechanisms by which IAPP gains toxic function include energy independent cell membrane penetration and induction of membrane depolarization. These processes have been correlated with solution biophysical observations of lipid bilayer catalyzed acceleration of amyloid formation. Although the relationship between amyloid formation and toxicity is poorly understood, the fact that conditions promoting one also favor the other suggests related membrane active structural states. Here, a novel high throughput screening protocol is described that capitalizes on this correlation to identify compounds that target membrane active species. Applied to a small library of 960 known bioactive compounds, we are able to report identification of 37 compounds of which 36 were not previously reported as active toward IAPP fiber formation. Several compounds tested in secondary cell viability assays also demonstrate cytoprotective effects. It is a general observation that peptide induced toxicity in several amyloid diseases (such as Alzhiemer’s and Parkinson’s) involves a membrane bound, preamyloid oligomeric species. Our data here suggest that a screening protocol based on lipid-catalyzed assembly will find mechanistically informative small molecule hits in this subclass of amyloid diseases.

Keywords: IAPP, amylin, toxicity, small molecules, HTF, high throughput screen, amyloid, Type 2 diabetes, lipids

Introduction

Amyloid related diseases affect an ever-growing percentage of the world’s population.1,2 This is due in large part to an aging population, as well as other factors such as diet and more sedentary lifestyles. The pathology within each disorder is due, in part, to the self-assembly of a disease specific protein. For neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, the self assembling proteins are Aβ and α-synuclein, respectively. Amyloid contributes to pathology in many other disease states including diabetes, cancer, and HIV.3–5

Cross β-sheet formation is a hallmark of amyloid pathology,6 but is not necessarily the origin of cytotoxicity.7 Amyloid fibers themselves have been implicated as the toxic species, either through growth at a membrane8–10 or as part of a multistep process involving preamyloid states.11 In cancer12 and HIV3, for example, fiber formation is central to gains of function. For other diseases, fibers often retain a degree of toxicity, but preamyloid toxins are dominant and therefore the principle therapeutic target.13 In Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and type II diabetes, for example, cytotoxicity is increasingly attributed to intermediate states of self assembly. Amyloid precursor states offer an incredible challenge as they are oligomeric in nature, membrane associated, and heterogeneous in size and conformational arrangement. Out of this ensemble of states arise species resulting in several interdependent gains-of-functions including membrane translocation, amyloidogenesis, subcellular localization, membrane associated self-assembly, and cell toxicity. The recent shift in focus from amyloid to precursor oligomeric states enjoys the benefit of hindsight. It has long been understood that correlation between amyloid burden in Alzheimer’s disease and manifestations of dementia are quantitatively poor. In our own work with diabetes related amyloid in vitro, we have shown that amyloid assembly can be suppressed without loss of cytotoxic potential (and vice-versa).14 We therefore hypothesize that a small molecule screen based on direct targeting of membrane-associated assembly intermediates would prove to be a productive approach in finding novel and mechanistically informative small molecules.

Human islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) is a 37-residue peptide cosecreted with insulin by the β-cells of the endocrine pancreas.5 Its normal function is thought to be hormonal, for example, providing autocrine and paracrine feedback.15 Pathological assembly of this protein is associated with β-cell death in type II and stem cell transplant failures in type I diabetes.16 Increasing evidence implicates membrane-bound oligomeric intermediates as central to initiating this β-cell pathology. This includes observation of puncta on plasma membrane, subsequent localization of such structures to mitochondria, and concentration dependent self-assembly that gives rise to cell-penetrating peptide-like gains of function.14 One consequence of this is the capacity of IAPP to cross membranes and cause dysfunction at subcellular compartments, such as the mitochondria, but only at toxic concentrations.

Lipid bilayer surfaces stabilize IAPP in a heterogeneous and predominantly α-helical set of conformational states.17,18 These states result in loss of membrane integrity and greatly accelerate the formation of amyloid fibers in vitro. Thus, lipid-catalyzed amyloid formation serves as a convenient surrogate to screen for compounds that may have an enhanced probability of interacting with or preventing the formation of structural states responsible for toxic gains of function. Here, we report the development and initial execution of a screen for molecules active in the context of lipid-catalyzed IAPP fiber formation. The assay was developed in a high throughput format based on reporting of an exogenously introduced dye and used to identify molecules from a redundant word library of known biologically active compounds.

The original kinetic traces of all initial hit compounds from the screen and selected dose dependence kinetic measurements to confirm inhibitory action are included as Supporting Information Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Related Supporting Information methods are also included.

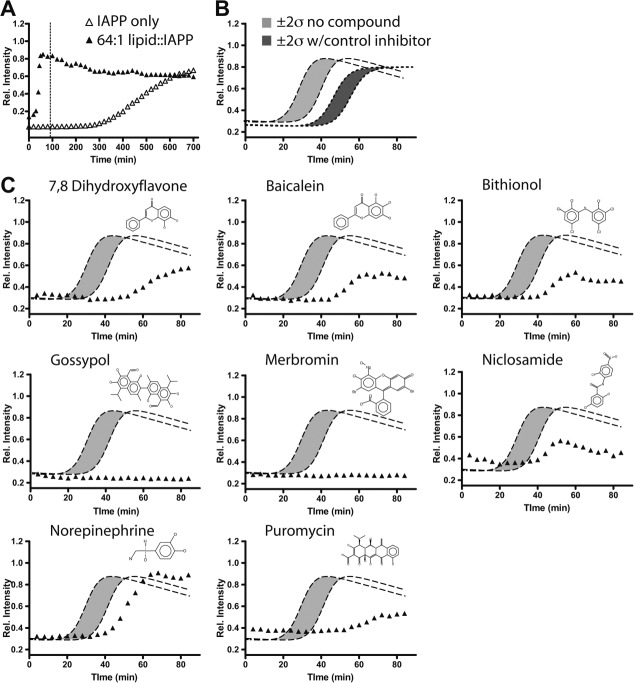

Figure 1.

Kinetic profiles of a lipid-catalyzed IAPP fiber formation and selected hits. A: Lipid-catalyzed compared with lipid-free conditions shown over a 12-hour period. The dotted line indicates the time period over which automated screening was monitored. B: Automated acquisition of lipid-catalyzed IAPP kinetics only (light grey) and insulin inhibited profiles (dark grey). A total of greater then 24 profiles were collected and independently fit [Eq.(1)]. Grey areas are flanked by dotted lines showing simulated profiles using the fitted parameters set to the average t50 ± 2 times the observed standard deviations. C: Representative hits from the screen are shown relative to the behavior of IAPP only reactions.

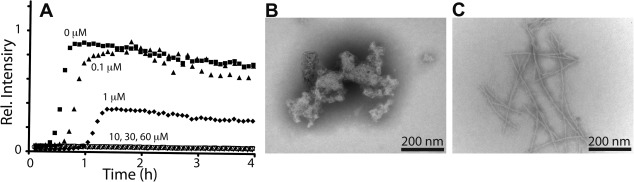

Figure 2.

Validation and characterization of merbromin effects. A: Merbromin strongly inhibits lipid-catalyzed fiber formation at sub-stoichiometric ratios. Kinetics of 10 μM IAPP monitored as a function of time with inclusion of the indicated concentrations of merbromin. B: Negative stain TEM of inhibited kinetics (no ThT positive signal) shows only amorphous aggregates. C: Control IAPP amyloid fibers prepared and visualized as a control. All kinetic profiles are representative of triplicate. Scale bar represents 200 nm.

Results

A high throughput screening protocol has been developed based on attenuation of lipid-catalyzed assembly of IAPP. Despite its diminished relevance to toxicity, fiber formation may nevertheless serve as a robust reporter for high throughput screening. Therefore, we use fiber formation as a tool, but operate in a bilayer catalyzed regime. Small molecules hits found using this approach will more likely have mechanisms that either displace IAPP from the membrane, or that directly inhibit conformation conversion of IAPP while bound to the membrane. Briefly, IAPP fiber formation reactions are initiated by dilution of 5 μL of a 40 μM IAPP stock solution in water to a final concentration of 10 μM protein in 20 μL of reaction buffer for a final buffer condition of 50 mM potassium phosphate, 150 mM KCl, pH 7.4. This is conducted using automated liquid handling in 384-well microtiter plate (See Material and Methods). The buffer also includes 50 μM ThT as a fluorescent reporter of the conversion to an amyloid state.19 Full kinetic profiles, rather than single point analyses are collected. This enables the potential for identifying agonists and antagonists, both or which are mechanistically useful. Collection of kinetic profiles also enables direct determination of changes in reaction midpoint, t50. This circumvents false positives that might occasionally arise from fluorescence quenching of ThT by the screened molecule. Under these conditions, the midpoint for amyloid assembly in lipid-free buffer is 7.6 ± 0.8 h. Addition of a phospholipid surface in the form of 640 μM (in monomer units) unilamellar liposomes formed from 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)] (DOPG). This catalyzes assembly yielding sigmoidal profiles with t50 = 35 ± 3min [Fig. 1(A)].

Modulators of IAPP assembly were identified by kinetic profile analysis of reactions performed in the presence of 10 μM of each screened compound. These were introduced before addition of protein using a pin-tool to transfer 20 nL from 10 mM DMSO stocks. Human insulin was used as a positive control inhibitor for this screen as we previously showed it to inhibit IAPP fiber formation under membrane catalyzed conditions.20 Addition of 40 μM insulin to standard compound free reactions gives a t50 of 51 ± 3 min. Thus, inhibition greater that two standard deviations from repeated experiments of our compound free reaction serves as our threshold for identifying hits in this assay [Fig. 1(B)].

Hits presented here were obtained from the MicroSource GenPlus library of 960 known bioactive compounds using a lipid to protein ratio of 64:1 DOPG:IAPP (Fig. 1). A total of 37 hits were found under this condition (see Supporting Information Fig. S1) using a semiautomated hit picking method based on ThT intensity and altered t50 values (Table 1). All hits were subjected to secondary fitting. Several initial hits were discarded due to fitting errors that arose, for example, from quenched ThT intensities that obscured the fact that t50 had not changed substantively from control values. All accepted hits resulted in either delay of t50 or complete inhibition of fiber formation within the time scale of the screen. No agonists were observed.

Table 1.

Calculated t50 Values from Each Initial Hit Compound

| Compound | t50 (min) | Compound | t50 (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone | 58.1 | Methyldopa | 45.2 |

| Acetylcarnitine | 46.0 | Mcl-186 | 32.5* |

| Aesculin | 48.3 | Nicolsamide | 44.3 |

| Baicalein | 54.0 | Nigericin sodium | 45.9 |

| Beta-carotene | 46.0 | Norepinephrine | 52.6 |

| Bithionol | 41.2 | Pararosaniline pamoate | 37.6* |

| Carboplatin | 48.3 | Pasiniazid | 46.8 |

| Celastrol | 52.4 | Phenazopyridine hydrochloride | 37.8* |

| Cisplatin | ND | Protoporphyrin ix | 45.4 |

| Cobalamine | 49.8 | Puromycin hydrochloride | 63.7 |

| Dibekacin | 45.2 | Pyrvinium pamoate | ND |

| Dipyrone | 46.6 | Quinalizarin | 50.5 |

| Gossypol-acetic acid complex | ND | Quinapril hydrochloride | 45.9 |

| Levodopa | 59.4 | Quipazine maleate | 45.2 |

| Levonordefrin | 55.1 | Salicyl alcohol | 46.9 |

| Lidocaine hydrochloride | 46.0 | Sanguinarine sulfate | 47.8 |

| Meclocycline sulfosalicylate | 55.3 | Sulfameter | 49.6 |

| Merbromin | ND | Tannic acid | 46.6 |

| Methylbenzethonium chloride | 48.4 | ||

Kinetic traces [see Fig. 1(B) and Supporting Information Fig. 1] were fit to Eq. (1) to determine the midpoint of the transition. Compounds resulting in no or minimal change in ThT intensity were also included as hits, but t50 values were not determined (ND).

Compounds marked with an asterisk where originally labeled as hits due to very low ThT intensity or automated fitting errors but were excluded from further analysis after secondary manual fitting.

Lipid catalyzed control t50 values were 35 ± 3 min.

A subset of screened compounds that delayed amyloid formation was validated by manually conducting dose dependence studies (Supporting Information Fig. S2). For example, merbromin, a topical antiseptic, wholly eliminated response in our plate based assay (Fig. 1). Such a response can be artifactual if the compound simply suppresses the reporter dye, ThT. Dose dependence studies instead reveal that merbromin acts as an effective substoichiometric inhibitor [Fig. 2(A)]. Fiber formation delay was evident at stoichiometries as low as 1:100, small molecule:protein. In addition, samples of IAPP incubated under both lipid and nonlipid-catalyzed assembly conditions reveal, by negative stain transmission electron microscopy (TEM), that merbromin promotes amorphous, nonfibrillar aggregation of IAPP [Fig. 2(B)]. These amorphous aggregates are stable, and do not go on to form amyloid on the days timescale. This suggests that inhibition of fiber formation by merbromin is due to promotion of off-pathway amorphous aggregation.

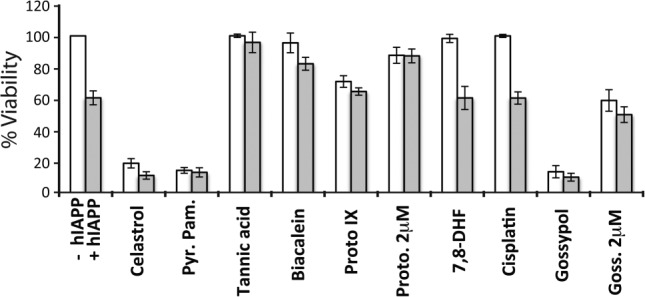

Small molecules identified by this screen have activity in cell viability assays. Here, we use INS-1, an insulinoma based β-cell line. Under our conditions, addition of 10 μM human IAPP results in ∼40% toxicity after 24 h as measured using a colorimetric assessment of viability. This is comparable to our own and other previously reported assays for IAPP induced toxicity.21,22 A sample of readily available hit compounds were obtained to test for rescue of IAPP induced cytotoxic (Fig. 3). A number of these compounds revealed cytoprotective effects when compared with carrier (DMSO) only controls. A subset of these molecules, equimolar celastrol, pyrvinium pamoate, protoporphyrin IX, and gossypol were intrinsically toxic resulting in reduced viability even in the absence of IAPP. This intrinsic toxic effect was attenuated for protoporphyrin IX and gossypol by reducing concentrations to 2 μM. In the case of protoporphyrin IX, the lowered concentration eliminated intrinsic toxicity and revealed a weakly cytoprotective effect on IAPP’s toxicity. Other molecules such as 7,8 dihydroxyflavone and cisplatin did not have intrinsic cytotoxicity at 10 μM, but failed to rescue IAPP toxicity. Tannic acid and baicalein showed a low level of intrinsic toxicity but effectively rescued of IAPP induced toxicity at 10 μM. These results show this screen was capable of identifying an array of molecules with varied effects on IAPP induced toxicity.

Figure 3.

Effect of readily available compounds on IAPP induced cell toxicity in INS-1 cells. Cell viability was assessed at 10 μM of specified hit compound (unless specified as 2 μM) with (grey) and without (white) 10 μM IAPP present. White bars are the control condition with hit compound present, without IAPP, and DMSO added to match solution conditions when IAPP is present (grey bar).

Discussion

The small molecule screen described here was designed to identify compounds that target membrane active states of amyloid formation. The weight of the publication record suggests that a subset of such membrane active states may be primarily responsible for toxic gains of function.13,23 In all, 37 hits were found and >25% (3 out of 8 tested) showed cellular activity. This is strong support of our stated working hypothesis underpinning the design of this screen. It is note worthy that no agonists of fiber formation were found by our approach. This may reflect the small size of our compound library. Alternatively, it may be that membrane bound intermediates are structurally distinct from amyloid itself and that stabilization of such species, regardless of form, results in a restricted capacity to nucleate. The mode of action of these identified compounds are likely varied, including both direct interaction with membrane bound states and/or prevention of membrane binding. We previously noted these possibilities in analysis of peptidomimetic inhibitors of IAPP.21

The hits identified here are a combination of known amyloid inhibitors and compounds not previously reported to have such activity. Three compounds (baicalein, 7,8 dihydroxyflavone, and aesculin) identified here as inhibitors of lipid-catalyzed IAPP assembly share a similar flavone-like scaffold, a class of compounds previously shown to have antiamyloid effects.24,25 Baicalein is known to interact with the amyloid precursor protein (APP) of Aβ and bias non-amyloidogenic cleavage,26 protecting cortical neurons from associated toxicity.27 The 7,8 dihydroxy-flavone has been reported to rescue memory defects in an Alzhiemer’s mouse model, albeit by TrkB activation mechanism, rather than a direct mechanism as seen for IAPP inhibition. Niclosamide is active against Aβ amyloid formation as well, altering amyloid morphology by EM.28 Lower levels of norepinephrine has been shown to correlate with tangles and amyloid plaque deposits in confirmed Alzheimer tissue,29 suggesting it may have cytoprotective effects in multiple amyloid systems. Both tannic acid30 and protoporphyrin IX31 demonstrate anti-amyloidogenic activity against Aβ, and IAPP has been shown to form strong complexes with heme groups by EPR.32 Cisplatin, shown here to inhibit IAPP amyloid formation but not toxicity, was shown to lack either function in Aβ.33 Many identified compounds, including bithionol, gossypol, puromycin and merbromin, have not been previously reported to have effects on amyloid formation. The inclusion of compounds and chemical scaffolds previously known to be amyloid active adds confidence to our identification of novel inhibitors and to the overall success of this screening approach.

Identifying drug-like compounds that can interfere with the function, or dysfunction, of an intrinsically disordered protein is a challenging task. Such systems likely have diverse assembly pathways to toxic states as a result of their conformational plasticity. As a result, it is not sufficient to merely identify inhibitors of a convenient observable (such as aggregation). Instead, approaches that bias the sampling of pre-amyloid states relevant to toxicity can dramatically focus the hits of a screen toward compounds appropriate for cellular and model organism of disease studies. The approach here is one such method that can be extended to other amyloid forming systems that act via related, membrane-active toxicity mechanisms.34–36

Material and Methods

Material

Human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide (IAPP) and a non-amyloid forming varient of IAPP from rat (rIAPP) were ordered from the W.M. Keck facility large-scale synthesis division (New Haven, CT). Compounds obtained for these studies include DOPG (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL), ThT (Acros, Geel, Belgium), DMSO (J.T. Baker, Center Valley, PA), and Merbromin (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland). The Microsource GenPlus library was accessed through the Yale Small Molecule Discovery Center.

Screening protocol

Lipids were prepared the day before any screening. These lipids were prepared using 100% DOPG, and extruded at 0.1 μm in buffer (50 mM PO4,150 mM KCl, pH 7.4) as previously described.37 Liposomes were diluted with screening buffer (66.6 mM PO4,200 mM KCl, pH 7.4) to 853 μM lipid. ThT was present in the buffer at 66.6 μM. These solutions were used as the standard assay buffer for this protocol and resulted in a final buffer condition of 50 mM PO4,150 mM KCl, pH 7.4 with 640 μM lipid and 50 μM ThT after addition of IAPP. Final DMSO concentration was less than 1%.

On the day of running the screen, IAPP was diluted to 40 μM in water from syringe filtered 1–1.5 mM stocks in 90% DMSO and kept at 4°C. Control wells were loaded by hand into 384-well Corning-3676, microtiter plates. Controls in the following number were added to each plate: 50 μM insulin (8X), 10 μM rIAPP (8X), 150 μM DOPG (16X), lipid-free (4X), and standard assay buffer (32X). A total of 15 μL of assay buffer was transferred to the 384-well plates (the 312 sample wells) by an Aquarius liquid handling robot (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). A pin-transfer tool was used to add screening compound to each well from the compound library plates. A total of 5 μL of the 40 μM IAPP water stock was then added to the plates by the same Aquarius robot. Plates were spun at 2000 rpm for 20 s to ensure all sample was properly in the bottom of each well. Plates were read at 4–15-min intervals using the EnVision plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), with up to 4 plates read at a time. Amyloid kinetics were monitored for up to 5 h.

Data collection was automated through the database system built into the screening facility. Data processing was performed in XLFit (IDBS), a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp.) add-on, and Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). XLFit enabled automated nonlinear regression with the return of specific values needed to simplify interpreting the data. The data was fit to a sigmoidal curve [Eq. (1)]. Hits were determined by comparison to the lipid-catalyzed control reactions. Deviations to the t50 and maximal ThT intensity from the controls were used to pick initial hits. Secondary fitting of initial hits in Prism identified three compounds that were ruled out for further consideration due to fitting errors in the automated approach.

Electron microscopy

Samples at specified concentrations of IAPP and compound and/or lipid were incubated in standard buffer. Pre-coated carbon copper EM grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) were glow discharged at 25 mA for 30 s. Sample was loaded onto grids and incubated for 30 s. Samples were blotted and rinsed then stained with 1% (w/v) PTA (phosphotungstic acid), pH 7.0. Images were acquired using a EM-900 transmission electron microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a MegaView soft imaging CCD camera (Olympus, Münster, Germany). Image scale noted by the inset bars in each image. All data shown were collected and recorded with the investigator blinded to sample identity. Each condition described was repeated and showed morphologically similar results.

Cellular viability assays

Cell viability assays were performed as previously described.14 Briefly, rat insulinoma cells (INS-1 832/13 clonal line), cultured in 24-well plates for 48 h, were exposed to media containing IAPP or carrier DMSO for 72 h in the presence or absence of specified compounds. DMSO was added to all media to ensure a constant 1% for all conditions. Thereafter, the medium was replaced with fresh medium without IAPP or compounds, and 100 μL CellTiter-Blue reagent (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) was added to each well. Following a 4 h incubation, at 37°C, the fluorescence of the resofurin product (ex/em 560/620) was measured using a FluoDia T70 fluorescence platereader (PTI, Birmingham, NJ). The percentage cell viability was determined from the ratio of the fluorescence of the treated cells to the control cells. Untreated wells were used as control, and wells with medium alone served as a blank. The percentage cell viability was determined from the ratio of the fluorescence of the treated cells to the control cells. The results presented are an average of 3–4 experiments carried out on separate days.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Paul Fletcher, Jane Merkel, and the Yale Center for Molecular Discovery for assistance in designing and performing this screen of their MicroSource Gen-Plus library. They also thank Prof. E. Rhoades and A. Nath for critical reading of this manuscript.

Glossary

- IAPP

human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide

- rIAPP

non-amyloidogenic rat variant of IAPP

- DOPG

1,2-dioleoyl-snglycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)

- Pyr.Pam.

pyrvinium pamoate

- Proto. IX

protoporphyrin IX

- 7,8 DHF

7,8 dihydroxyflavone

- Goss

gossypol

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- Holtzman JLL. Are we prepared to deal with the Alzheimer’s disease pandemic? Clin Pharm Therap. 2010;88:563–565. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Xie X, Wang S, Wang Y, Jonas JB. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in China. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2008;116:69–70. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munch J, Rucker E, Standker L, Adermann K, Goffinet C, et al. Semen-derived amyloid fibrils drastically enhance HIV infection. Cell. 2007;131:1059–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama K, Tsutsumi S, Suzuki T, Horie-Inoue K, Ikeda K, Kaneshiro K, Fujimura T, Kumagai J, Urano T, Sakaki Y, Shirahige K, Sasano H, Takahashi S, Kitamura T, Ouchi Y, Aburatani H, Inoue S. Amyloid precursor protein is a primary androgen target gene that promotes prostate cancer growth. Cancer Res. 2009;69:137–142. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppener JW, Ahren B, Lips CJ. Islet amyloid and type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:411–419. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008103430607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick AWP, Debelouchina GT, Bayro MJ, Clare DK, Caporini MA, Bajaj VS, Jaroniec CP, Wang L, Ladizhansky V, Müller SA, MacPhee CE, Waudby CA, Mott HR, De Simone A, Knowles TPJ, Saibil HR, Vendruscolo M, Orlova EV, Griffin RG, Dobson CM. Atomic structure and hierarchical assembly of a cross-β amyloid fibril. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5468–5473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219476110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel MF, Khemtemourian L, Kleijer CC, Meeldijk HJ, Jacobs J, Verkleij AJ, de Kruijff B, Killian JA, Hoppener JW. Membrane damage by human islet amyloid polypeptide through fibril growth at the membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6033–6038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708354105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciacca MFM, Brender JR, Lee D-KK, Ramamoorthy A. Phosphatidylethanolamine enhances amyloid fiber-dependent membrane fragmentation. Biochemistry. 2012;51:7676–7684. doi: 10.1021/bi3009888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparr E, Engel MF, Sakharov DV, Sprong M, Jacobs J, de Kruijff B, Hoppener JW, Killian JA. Islet amyloid polypeptide-induced membrane leakage involves uptake of lipids by forming amyloid fibers. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciacca MFM, Kotler SA, Brender JR, Chen J, Lee D-KK, Ramamoorthy A. Two-step mechanism of membrane disruption by Aβ through membrane fragmentation and pore formation. Biophys J. 2012;103:702–710. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Reumers J, Couceiro JR, De Smet F, Gallardo R, Rudyak S, Cornelis A, Rozenski J, Zwolinska A, Marine JC, Lambrechts D, Suh YA, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J. Gain of function of mutant p53 by coaggregation with multiple tumor suppressors. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:285–295. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fändrich M. Oligomeric intermediates in amyloid formation: structure determination and mechanisms of toxicity. J Mol Biol. 2012;421:427–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magzoub M, Miranker AD. Concentration-dependent transitions govern the subcellular localization of islet amyloid polypeptide. FASEB J. 2012;26:1228–1238. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-194613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AE, Jang J, Gurlo T, Carty MD, Soeller WC, Butler PC. Diabetes due to a progressive defect in beta-cell mass in rats transgenic for human islet amyloid polypeptide (HIP Rat): a new model for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53:1509–1516. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.6.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter KJ, Abedini A, Marek P, Klimek AM, Butterworth S, Driscoll M, Baker R, Nilsson MR, Warnock GL, Oberholzer J, Bertera S, Trucco M, Korbutt GS, Fraser PE, Raleigh DP, Verchere CB. Islet amyloid deposition limits the viability of human islet grafts but not porcine islet grafts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4305–4310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909024107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayasinghe SA, Langen R. Lipid membranes modulate the structure of islet amyloid polypeptide. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12113–12119. doi: 10.1021/bi050840w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath A, Miranker AD, Rhoades E. A membrane-bound antiparallel dimer of rat islet amyloid polypeptide. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:10859–10862. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe LS, Calabrese MF, Nath A, Blaho DV, Miranker AD, Xiong Y. Protein-induced photophysical changes to the amyloid indicator dye thioflavin T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16863–16868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002867107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JD, Williamson JA, Miranker AD. Interaction of membrane-bound islet amyloid polypeptide with soluble and crystalline insulin. Protein Sci. 2008;17:1850–1856. doi: 10.1110/ps.036350.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebda JA, Saraogi I, Magzoub M, Hamilton AD, Miranker AD. A peptidomimetic approach to targeting pre-amyloidogenic states in type II diabetes. Chem Biol. 2009;16:943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatarek-Nossol M, Yan L-MM-MM, Schmauder A, Tenidis K, Westermark G, Kapurniotu A. Inhibition of IAPP amyloid-fibril formation and apoptotic cell death by a designed IAPP amyloid- core-containing hexapeptide. Chem Biol. 2005;12:797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughey B, Lansbury PT. Protofibrils, pores, fibrils, and neurodegeneration: separating the responsible protein aggregates from the innocent bystanders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:267–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.010302.081142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao P, Raleigh DP. Analysis of the inhibition and remodeling of islet amyloid polypeptide amyloid fibers by flavanols. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2670–2683. doi: 10.1021/bi2015162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porat Y, Abramowitz A, Gazit E. Inhibition of amyloid fibril formation by polyphenols: structural similarity and aromatic interactions as a common inhibition mechanism. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006;67:27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-QQ, Obregon D, Ehrhart J, Deng J, Tian J, Hou H, Giunta B, Sawmiller D, Tan J. Baicalein reduces β-amyloid and promotes nonamyloidogenic amyloid precursor protein processing in an Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mouse model. J Neurosci Res. 2013;91:1239–1246. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeau A, Esclaire F, Rostène W, Pélaprat D. Baicalein protects cortical neurons from beta-amyloid (25-35) induced toxicity. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2199–2202. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200107200-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari M, Roberts JK, Desutter B, Duong KT, Tingling J, Fawver JN, Schall HE, Kahle M, Murray IVJ. Hydralazine modifies Aβ fibril formation and prevents modification by lipids in vitro. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10371–10380. doi: 10.1021/bi101249p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaddurah-Daouk R, Rozen S, Matson W, Han X, Hulette CM, Burke JR, Doraiswamy PM, Welsh-Bohmer KA. Metabolomic changes in autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K, Hasegawa K, Naiki H, Yamada M. Anti-amyloidogenic activity of tannic acid and its activity to destabilize Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibrils in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1690:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett D, Cutler P, Heales S, Camilleri P. Hemin and related porphyrins inhibit β-amyloid aggregation. FEBS Lett. 1997;417:249–251. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Dey SG. Heme bound amylin: Spectroscopic characterization, reactivity, and relevance to Type 2 diabetes. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:5226–5235. doi: 10.1021/ic4001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnham KJ, Kenche VB, Ciccotosto GD, Smith DP, Tew DJ, Liu X, Perez K, Cranston GA, Johanssen TJ, Volitakis I, Bush AI, Masters CL, White AR, Smith JP, Cherny RA, Cappai R. Platinum-based inhibitors of amyloid-β as therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6813–6818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800712105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Last NB, Miranker AD. Common mechanism unites membrane poration by amyloid and antimicrobial peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:6382–6387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219059110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Last NB, Schlamadinger DE, Miranker AD. A common landscape for membrane-active peptides. Protein Sci. 2013;22:870–882. doi: 10.1002/pro.2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebda JA, Miranker AD. The interplay of catalysis and toxicity by amyloid intermediates on lipid bilayers: Insights from Type II diabetes. Ann Rev Biophys. 2009;38:125–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JD, Miranker AD. Phospholipid catalysis of diabetic amyloid assembly. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:1175–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.