Abstract

Bacterial microcompartments (MCPs) are subcellular organelles that are composed of a protein shell and encapsulated metabolic enzymes. It has been suggested that MCPs can be engineered to encapsulate protein cargo for use as in vivo nanobioreactors or carriers for drug delivery. Understanding the stability of the MCP shell is critical for such applications. Here, we investigate the integrity of the propanediol utilization (Pdu) MCP shell of Salmonella enterica over time, in buffers with various pH, and at elevated temperatures. The results show that MCPs are remarkably stable. When stored at 4°C or at room temperature, Pdu MCPs retain their structure for several days, both in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, Pdu MCPs can tolerate temperatures up to 60°C without apparent structural degradation. MCPs are, however, sensitive to pH and require conditions between pH 6 and pH 10. In nonoptimal conditions, MCPs form aggregates. However, within the aggregated protein mass, MCPs often retain their polyhedral outlines. These results show that MCPs are highly robust, making them suitable for a wide range of applications.

Keywords: bacterial microcompartments, protein encapsulation, propanediol utilization, microcompartment stability

Introduction

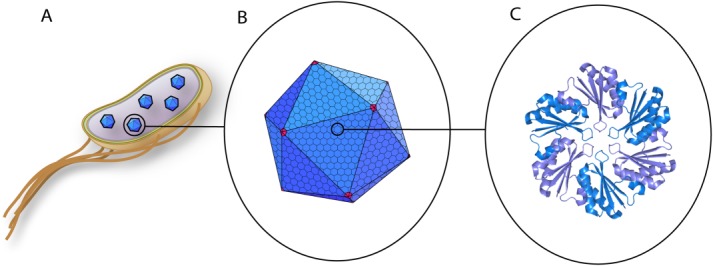

Microcompartments (MCPs) are structures utilized by bacteria to organize and sequester enzymes and the biochemical pathways they catalyze.1,2 The propanediol utilization (Pdu) MCP, found in several enteric bacteria, consists of a protein shell and encapsulated enzymes involved in 1,2-propanediol (1,2-PD) catabolism [Fig. 1(A)].3 In the first two steps of the Pdu pathway, the substrate 1,2-PD is converted by the enzyme PduCDE to propionaldehyde, which is then converted to propionyl-CoA by PduP.4,5 It is proposed that these first two steps within the Pdu MCP are encapsulated in order to sequester the toxic intermediate propionaldehyde.6 The MCP shell, approximately 125–175 nm in diameter, is made up of thousands of copies of protein subunits, of which there are nine different types [Fig. 1(B)].7–10 The structures of several of these shell proteins have been solved, providing insight on how the subunits assemble to form the polyhedral shell.11–13 The major constituents of the Pdu MCP shell form homohexamers and self-assemble to create the facets of the MCP [Fig. 1(C)]. The vertices are thought to be composed of PduN, a less abundant shell protein which form homopentamers, and thus possess the five-fold axis of symmetry required to form a vertex.14,15

Figure 1.

Diagram of bacterial MCPs shown with increasing detail. A: S. enterica expressing several in vivo MCPs. The inner and outer membranes are shown in yellow, peptidoglycan layer in green, and the cytosol in purple. B: The Pdu MCP is composed of many repeating units of hexameric proteins, shown in blue, which form the facets of the polyhedra. PduN, shown in red, is thought to assemble as a homopentamer and form the vertices of the Pdu MCP. C: Crystal structure of PduA (PDB ID: 3NGK),12 a shell protein that crystallizes as a homohexamer. Adjacent monomers are shown in different colors. Reprinted from Current Opinion in Biotechnology, Vol. 24, Issue 4, E.Y. Kim and D. Tullman-Ercek, Engineering nanoscale protein compartments for synthetic organelles, pp. 627–632. Copyright 2013, with permission from Elsevier.

Recent studies have shown that the Pdu MCP is capable of encapsulating a variety of heterologous protein cargo.16,17 This feature can be exploited to create nanobioreactors by encapsulating enzymes for synthetic pathways,18 as has been done for virus capsids,19–21 which share an analogous structural architecture. In this regard, Lawrence et al. showed that a Pdu-based ethanol nanobioreactor is functional both in vivo and in vitro.17 In addition to creating nanobioreactors, the Pdu MCP can also be adapted for use as protein cages in drug delivery. Polyhedral virus capsids have already shown promise in this field,22–25 and the increased size of MCPs may permit additional cargo loading per particle.

One of the barriers currently limiting progress towards practical application of bacterial MCPs is the lack of stability data. Studies on virus capsids show that protein capsids can range from being exceptionally stable, such as in the case of bacteriophage MS2, to being transient or metastable, as with cowpea chlorotic mottle virus.26 Recently, Sinha et al. have identified key amino acids in PduA that govern proper shell assembly in the first study to investigate the phenotypic effects of structural mutations in the Pdu MCP.27 Here, we seek to investigate the robustness of the Pdu MCP shell with respect to time, pH, and temperature. We find that MCPs are remarkably stable and retain their structure for several days, and can tolerate temperatures up to 60°C without apparent degradation. MCPs are, however, sensitive to pH and require conditions between pH 6 and pH 10. We conclude that MCPs maintain their integrity under a variety of physiologically relevant conditions, making them suitable for a wide variety of applications. These results also provide a starting point for engineering MCPs with enhanced stability.

Results

MCP integrity over time

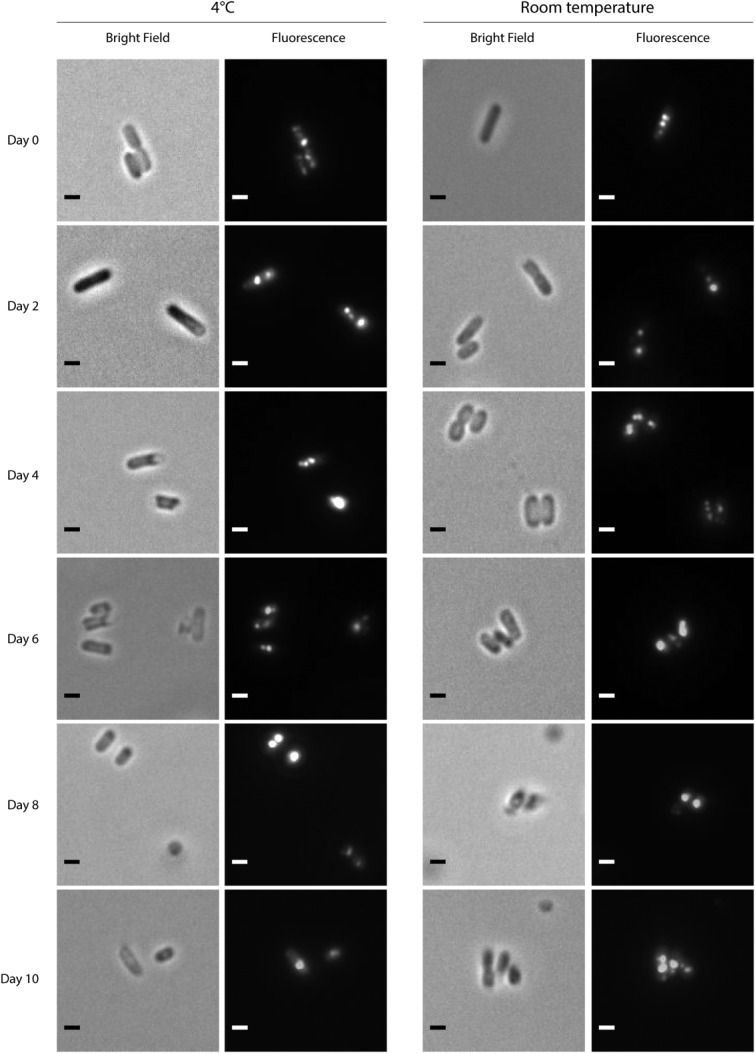

We first assessed the stability of the Pdu MCP in vivo using fluorescence microscopy. S. enterica was induced to form MCPs while expressing a reporter construct, a fusion of the N-terminus of PduP to green fluorescent protein (PduP1–18-GFP). The GFP is targeted to the MCP lumen by this N-terminal targeting sequence from the PduP enzyme, and the encapsulated reporter was shown previously to appear as fluorescent puncta in such cells.16,28 The cells were then resuspended in buffer with 100 μg/mL of kanamycin to halt further protein production. Cells were imaged every 48 h over the course of 10 days. Fluorescent puncta can be seen within cells for several days whether held at 4°C or at room temperature (Fig. 2; additional fields of view available in Supporting Information 1). After 8 days, we note that a substantial number of the cells contain only one or two large fluorescent puncta that are often found in the polar region. While these may still be intact MCPs, another potential explanation is that the MCPs and the reporter protein formed aggregates. In agreement with this latter hypothesis, a time course of cells expressing PduP1–18-GFP in the absence of MCP induction shows diffuse fluorescence for several days, and also shows potential aggregation after eight days, as seen by the emergence of fluorescent puncta (Supporting Information 2, Fig. S1). Taking these data together, we conclude that the MCPs are stable for at least 6 days under the conditions tested.

Figure 2.

Fluorescence microscopy time course of S. enterica expressing encapsulation reporter PduP1–18-GFP. Cells are resuspended in PBS with 100 μg/mL of kanamycin to halt further protein production. The microcompartment-encapsulated reporter protein appears as fluorescent puncta. The camera exposure times were 800 ms. Scale bar represents 1 μm.

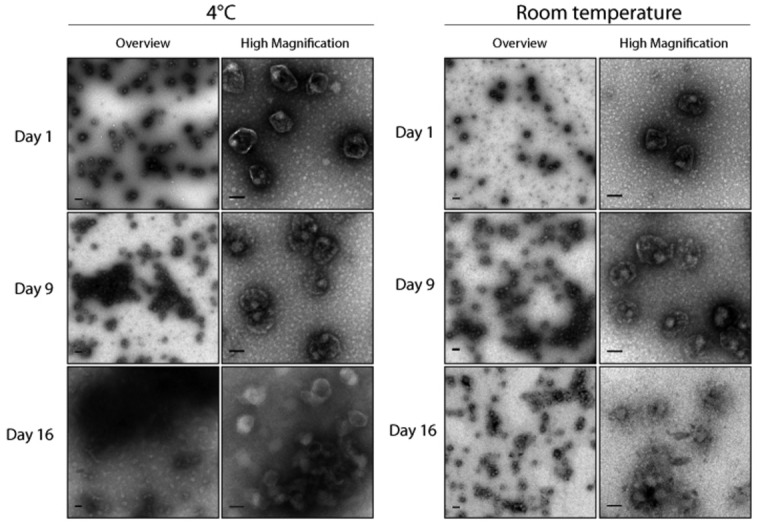

We then assessed the stability of the Pdu MCP in vitro. Purified MCPs from S. enterica expressing the encapsulation reporter PduP1–18-GFP were held at either 4°C or at room temperature over the course of several days, and imaged using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The results show that after nine days, a fraction of MCPs form aggregates, but individual MCPs appear to retain their characteristic shape and defined edges (Fig. 3). After sixteen days, the MCP shells appear deteriorated and no longer have clear, defined edges. These MCPs also appear to stain differently, possibly due to the loss of the encapsulated PduP1–18-GFP and/or natively encapsulated proteins.

Figure 3.

TEM images of an in vitro time course of purified Pdu MCPs encapsulating PduP1–18-GFP. MCPs were held at either 4°C or at room temperature. Two representative images are shown for each time point—one overview image (scale bar represents 200 μm), and one higher magnification image (scale bar represents 100 μm) to highlight the details of the MCPs.

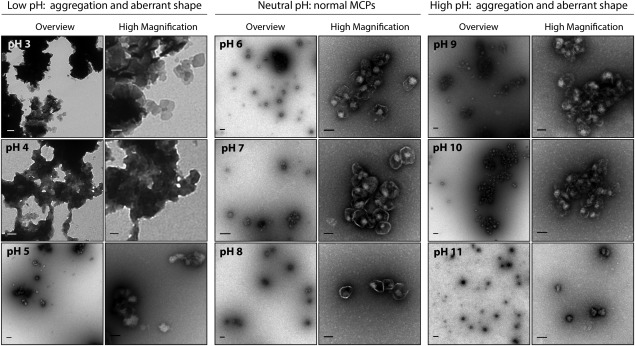

MCP integrity at various pH

Next, we probed the stability of purified MCPs in buffers of different pH. To ensure that stability is unaffected by the presence of the heterologous protein reporter, both native Pdu MCPs and those encapsulating PduP1–18-GFP were examined. We observed no significant difference between native MCPs and those isolated from cells that coexpress the PduP1–18-GFP construct, indicating that our reporter protein is not substantially affecting the stability of the protein shell (Fig. 4 and Supporting Information 2, Fig. S2). TEM images show that individual MCPs display normal morphology between pH 6 and pH 10, although large aggregates are observed at pH 9 and above (Fig. 4). At pH 10 and 11, MCP bodies appear to lose characteristic features and are smaller in size, with approximately 100 nm Feret’s diameters, (Supplementary Material 2, Fig. S3) than untreated MCPs, which typically have 125 to 175 nm Feret’s diameters.3,7,29 At pH 5, we again observe the deterioration of MCP structure, as well as the decrease in size. The size analysis could not be performed on samples that were incubated below pH 5 due to the extensive aggregation that occurred.

Figure 4.

TEM images of purified MCPs encapsulating PduP1–18-GFP in buffers of varying pH. Two representative images are shown for each pH—one overview image (scale bar represents 200 μm), and one higher magnification image (scale bar represents 100 μm) to highlight the details of the MCPs.

Heat-induced aggregation of MCPs

We characterized the heat stability of purified Pdu MCPs in two ways. One method to characterize the thermal stability of proteins is a thermal shift assay. In this assay, purified Pdu MCPs are incubated with the fluorescent dye SYPRO Orange, which is strongly quenched by water. As proteins denature, the dye nonspecifically binds to hydrophobic surfaces. Fluorescence is measured as the temperature is increased at a rate of 1°C per minute. Using this assay, we find the melting point, as defined as the inflection point in the thermal shift curve, to be 53.52°C and 52.09°C for the native and GFP-containing MCPs, respectively (Supporting Information 2, Fig. S4). Given the similarity in stability between native and GFP-encapsulating MCPs, only those encapsulating the reporter protein were used for the remaining experiments.

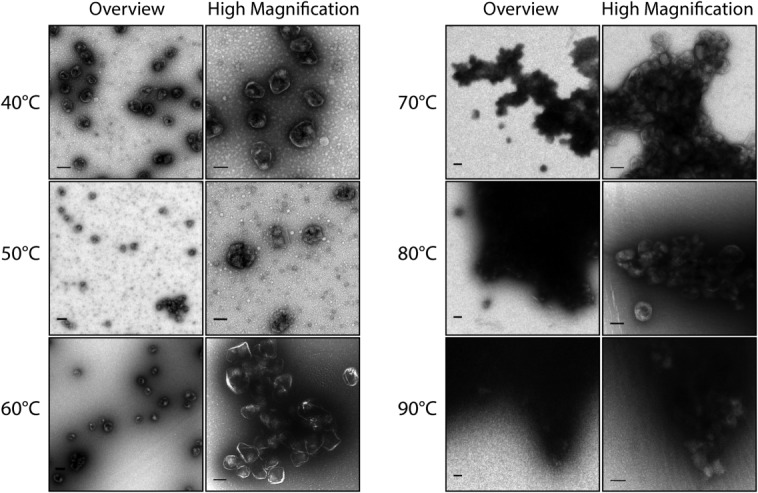

We next incubated the MCPs encapsulating PduP1–18-GFP at elevated temperatures for 15 min then cooled to 4°C for storage. The MCPs appear, by TEM, to be normal in size and retain their defined edges at temperatures up to 60°C, although we observe clustering of MCPs at 50°C and above (Fig. 5). This result corresponds to the approximate melting temperature as measured by the thermal shift assay. Analysis of the Feret’s diameter as a function of temperature reveals no significant differences in size as the temperature is increased (Supporting Information 2, Fig. S5). At 70°C, the majority of MCPs are found within large aggregates. Surprisingly, within these aggregates, the outline of individual MCP bodies can be seen up to 90°C.

Figure 5.

TEM images of heat-treated purified MCPs encapsulating PduP1–18-GFP. MCPs were incubated at elevated temperatures for 15 min then cooled to 4°C. Two representative images are shown for each temperature—one overview image (scale bar represents 200 μm), and one higher magnification image (scale bar represents 100 μm) to highlight the details of the MCPs.

We used dynamic light scattering (DLS) to complement TEM for investigating the process of aggregation. A representative size distribution profile for purified MCPs without heat treatment shows general agreement with TEM images (Supporting Information 2, Fig. S6). As temperature is raised to 50°C, a second peak is detected, corresponding to larger sized particles (Supporting Information, Fig. S7). The appearance of these larger particles at 50°C is in agreement with both the thermal shift assay and the appearance of aggregates in the TEM images. The proportion of signal intensity corresponding to the aggregate peak increases with increasing temperature. At temperatures above 65°C, the particle size in the sample is too polydisperse for size distribution analysis.

Discussion

The Pdu MCP is remarkably stable over time and at elevated temperatures. We found that MCPs are able to retain their structure for over one week at 4°C or at room temperature, and can endure temperatures up to 60°C, with slight aggregation in vitro, but otherwise without any visible aberrations to the shell structure. This makes MCPs suitable for a diversity of applications. As an example, the high temperature stability of MCPs could allow for expanding its use as in vivo nanobioreactors for pathways that may be unique to thermophilic organisms incubated at elevated temperatures.

We observe that MCPs require environmental conditions between pH 6 and pH 10. However, the disruption of the MCP shell below pH 6 may be exploited for use in drug delivery. Many particles of similar size to MCPs, such as virus capsids, are taken up by cells through endosomes; endosomal escape of therapeutics before their degradation in the lysosome remains a major challenge for effective drug delivery. An MCP-based delivery system can exploit the lowered pH in maturing endosomes, which reaches pH 5, to disassemble and release its cargo.30–32 Coupled with encapsulated cytolysin proteins, the now-released therapeutic cargo could escape the endosome and release into the cytoplasm of target cells.

It is interesting that TEM images of partially disrupted MCPs, either by high temperature or extreme pH, show that MCP bodies persist, though they are misshapen and/or smaller in size than untreated MCPs. We speculate that certain components of the MCP shell, of which there are nine known protein constituents, are more susceptible to denaturation than others. The differential degradation among the shell constituents may cause the shell to collapse and could explain the aberrantly-shaped and smaller-sized bodies observed in TEM. For instance, the unfolding of all but one hexameric shell constituent, such as PduA, and the pentameric shell protein PduN, may result in the formation of a unique, smaller, stable structure. Such changes to size and geometry have previously been observed in virus capsids. For example, in vitro assembly studies of the CCMV capsid, in which the N-terminal 34 amino acids of the coat protein have been removed, results in a statistically predictable distribution of the native T=3 capsids composed of 90 copies of the coat protein dimer, the T=2 capsid composed of 60 dimers, and the T=1 capsid composed of 30 dimers.22 Vernizzi et al. modeled possible geometries of a two-component system and show that many different shapes, ranging from icosahedron to sphere, can be formed by simply changing the ratio of the two components.33 With additional shell components, such as some of the nine constituents of the Pdu MCP shell, even more complex sizes and structures are possible.

The robust nature of the Pdu MCP makes it a promising platform for applications in biotechnology and biomedicine. Further enhancements in stability may be desirable for particular applications, such as those requiring a buffer at low pH. To this end, we anticipate studies on the stability of individual shell proteins will be informative and enable the engineering of MCPs for these conditions.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions

The bacterial strain used in this study is Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Cultures were grown in 2 ml of LB Miller medium overnight and were diluted 1:1000 into 400 mL of no-carbon-E (NCE) minimal medium supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4, 50 µM ferric citrate, 0.5% succinate, 0.4% 1,2-propanediol, and antibiotic (17 μg/mL chloramphenicol) in a 2 L flask.34 All growth was done at 37°C in an orbital shaker at 225 rpm. Upon reaching OD600 = 0.4, 0.02% arabinose was added to induce the production of the reporter protein. After five additional hours of growth, 100 μL aliquots of cell culture were set aside for microscopy, and the rest of the cells were harvested by centrifugation for Pdu MCP purification.

Fluorescence microscopy

Bacteria were viewed using a Nikon Ni-U upright microscope with a 100x, 1.45 n.a. plan apochromat objective. Images were captured using an Andor Clara-Lite digital camera. Fluorescence images were collected using a C-FL Endow GFP HYQ band pass filter.

Pdu MCP purification

The MCP purification protocol was performed as previously described.10

Electron microscopy

Totally, 10 μL of purified MCPs, at a concentration of 100 μg/mL, were placed on 400 mesh formvar coated copper grids with a carbon film for 2 min. The grids were washed three times with deionized water, then stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate for 1 min. Samples were observed and photographed with a FEI Tecnai T12 transmission electron microscope and a Gatan Ultrascan 1000 camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA).

Size distribution analysis

TEM images were imported into ImageJ and the ellipse tool was used to manually draw an ellipse circumscribing each MCP. The measure function was used to determine the Feret’s diameter for at least 100 MCPs per condition tested, obtained from random fields of view. The diameters were averaged and reported as a bar graph, with the error bars representing one standard deviation from the mean Feret’s diameter for MCPs at that condition.

In vivo stability time course

Totally 100 μL aliquots of cell culture were centrifuged for 5 min at 5000g to pellet the cells. The supernatant was removed and the cells were resuspended in 400 μL phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 100 μg/mL kanamycin to halt protein production. Samples were then kept at 4°C or at room temperature until the time indicated.

Incubation at various pH

Totally, 100 μL of purified MCPs, at a concentration of 300 μg/mL, were centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min at 21,000g to pellet the MCPs. The supernatant was removed and the MCPs were resuspended in 100 μL of the appropriate buffer. See Supporting Information Table T1 for a list of buffers used. Samples were stored in buffer at 4°C for up to 2 h until samples were processed for TEM.

Thermal shift assay

Totally, 7 μg of purified Pdu MCPs were incubated with 15x SYPRO Orange (Life Technologies; the absolute concentration of SYPRO Orange is not disclosed by the manufacturer) in a total volume of 25 μL. Measurements were recorded in a Bio-Rad CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System using the Channel 6 FRET filter settings (excitation 450–490 nm, detection 560–580 nm). The temperature was raised from 35°C to 80°C at a rate of 1°C/min, and measurements were recorded every 12 s. The data shown is averaged over three replicates run in parallel.

Temperature incubation on purified MCPs

Totally, 50 μL of purified MCPs, at a concentration of 300 μg/mL, were incubated at the specified temperature for 15 min, then cooled and stored at 4°C for up to 2 h until samples were processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Dynamic light scattering

Totally, 100 μL of purified MCPs, at a concentration of 750 μg/mL, were placed in 8.5 mm disposable spectrophotometry cuvettes and analyzed on a Malvern Instruments Zen 3600. For temperature-induced aggregation studies, the instrument was programmed to increment the temperature by 5°C, equilibrate for 5 min, and record.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Matthew Francis, Jeff Glasgow, and Christopher Jakobson for helpful discussions.

Glossary

- CCMV

cowpea chlorotic mosaic virus

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MCP

microcompartment

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- Pdu

propanediol utilization

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- Cheng S, Liu Y, Crowley CS, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Bacterial microcompartments: their properties and paradoxes. Bioessays. 2008;30:1084–1095. doi: 10.1002/bies.20830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates TO, Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Shively JM. Protein-based organelles in bacteria: carboxysomes and related microcompartments. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:681–691. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havemann GD, Bobik TA. Protein content of polyhedral organelles involved in coenzyme B12-dependent degradation of 1,2-propanediol in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:5086–5095. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.17.5086-5095.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobik TA, Xu Y, Jeter RM, Otto KE, Roth JR. Propanediol utilization genes (pdu) of Salmonella typhimurium: three genes for the propanediol dehydratase. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6633–6639. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6633-6639.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal NA, Havemann GD, Bobik TA. PduP is a coenzyme-a-acylating propionaldehyde dehydrogenase associated with the polyhedral bodies involved in B12-dependent 1,2-propanediol degradation by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Arch Microbiol. 2003;180:353–361. doi: 10.1007/s00203-003-0601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson EM, Bobik TA. Microcompartments for B12-dependent 1,2-propanediol degradation provide protection from DNA and cellular damage by a reactive metabolic intermediate. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2966–2971. doi: 10.1128/JB.01925-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havemann GD, Sampson EM, Bobik TA. PduA is a shell protein of polyhedral organelles involved in coenzyme B(12)-dependent degradation of 1,2-propanediol in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium LT2. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1253–1261. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.5.1253-1261.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JB, Dinesh SD, Deery E, Leech HK, Brindley AA, Heldt D, Frank S, Smales CM, Lunsdorf H, Rambach A, Gass MH, Bleloch A, McClean KJ, Munro AW, Rigby SEJ, Warren MJ, Prentice MB. Biochemical and structural insights into bacterial organelle form and biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14366–14375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JB, Frank S, Bhella D, Liang MZ, Prentice MB, Mulvihill DP, Warren MJ. Synthesis of empty bacterial microcompartments, directed organelle protein incorporation, and evidence of filament-associated organelle movement. Mol Cell. 2010;38:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Cheng S, Fan C, Bobik TA. The PduM protein is a structural component of the microcompartments involved in coenzyme B(12)-dependent 1,2-propanediol degradation by Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:1912–1918. doi: 10.1128/JB.06529-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley CS, Sawaya MR, Bobik TA, Yeates TO. Structure of the PduU shell protein from the Pdu microcompartment of Salmonella. Structure. 2008;16:1324–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley CS, Cascio D, Sawaya MR, Kopstein JS, Bobik TA, Yeates TO. Structural insight into the mechanisms of transport across the Salmonella enterica Pdu microcompartment shell. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37838–37846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang A, Warren MJ, Pickersgill RW. Structure of PduT, a trimeric bacterial microcompartment protein with a 4Fe-4S cluster-binding site. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:91–96. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910050201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Sinha S, Fan C, Liu Y, Bobik TA. Genetic analysis of the protein shell of the microcompartments involved in coenzyme B12-dependent 1,2-propanediol degradation by Salmonella. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:1385–1392. doi: 10.1128/JB.01473-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley NM, Gidaniyan SD, Liu Y, Cascio D, Yeates TO. Bacterial microcompartment shells of diverse functional types possess pentameric vertex proteins. Protein Sci. 2013;22:660–665. doi: 10.1002/pro.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C, Cheng S, Liu Y, Escobar CM, Crowley CS, Jefferson RE, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Short N-terminal sequences package proteins into bacterial microcompartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7509–7514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913199107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AD, Frank S, Newnham S, Lee MJ, Brown IR, Xue W-F, Rowe ML, Mulvihill DP, Prentice MB, Howard MJ, Warren MJ. Solution structure of a bacterial microcompartment targeting peptide and its application in the construction of an ethanol bioreactor. ACS Synthetic Biology. 2014;3:454–465. doi: 10.1021/sb4001118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Tullman-Ercek D. Engineering nanoscale protein compartments for synthetic organelles. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:627–632. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriezema DM, Aragones MC, Elemans JAAW, Cornelissen JJLM, Rowan AE, Nolte RJM. Self-assembled nanoreactors. Chem Rev. 2005;105:1445–1489. doi: 10.1021/cr0300688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil A, Reichhardt C, Johnson B, Prevelige PE, Douglas T. Genetically programmed in vivo packaging of protein cargo and its controlled release from bacteriophage P22. Angewandte Chemie-Int Ed. 2011;50:7425–7428. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow JE, Capehart SL, Francis MB, Tullman-Ercek D. Osmolyte-mediated encapsulation of proteins inside MS2 viral capsids. ACS Nano. 2012;6:8658–8664. doi: 10.1021/nn302183h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow JE. Tullman-Ercek D Production and applications of engineered viral capsids. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 98:5847–5858. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Brown WL, Stockley PG. Cell-specific delivery of bacteriophage-encapsidated ricin A chain. Bioconjug Chem. 1995;6:587–595. doi: 10.1021/bc00035a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs EW, Hooker JM, Romanini DW, Holder PG, Berry KE, Francis MB. Dual-surface-modified bacteriophage MS2 as an ideal scaffold for a viral capsid-based drug delivery system. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:1140–1147. doi: 10.1021/bc070006e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Wen H, Wen Q, Chen X, Wang Y, Xuan W, Liang J, Wan S. Cucumber mosaic virus as drug delivery vehicle for doxorubicin. Biomaterials. 2013;34:4632–4642. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katen S, Zlotnick A. The thermodynamics of virus capsid assembly. Methods Enzymol. 2009;455:395–417. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)04214-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Cheng S, Sung YW, McNamara DE, Sawaya MR, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Alanine scanning mutagenesis identifies an asparagine-arginine-lysine triad essential to assembly of the shell of the pdu microcompartment. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:2328–2345. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EY, Tullman-Ercek D. A rapid flow cytometry assay for the relative quantification of protein encapsulation into bacterial microcompartments. Biotechnol J. 2014;9:348–354. doi: 10.1002/biot.201300391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobik TA, Havemann GD, Busch RJ, Williams DS, Aldrich HC. The propanediol utilization (pdu) operon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 includes genes necessary for formation of polyhedral organelles involved in coenzyme B(12)-dependent 1, 2-propanediol degradation. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5967–5975. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.5967-5975.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipe DM, Jesurum A, Murphy RF. Absence of Na+,K(+)-ATPase regulation of endosomal acidification in K562 erythroleukemia cells. Analysis via inhibition of transferrin recycling by low temperatures. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3469–3474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killisch I, Steinlein P, Romisch K, Hollinshead R, Beug H, Griffiths G. Characterization of early and late endocytic compartments of the transferrin cycle. Transferrin receptor antibody blocks erythroid differentiation by trapping the receptor in the early endosome. J Cell Sci 103 (Part. 1992;1):211–232. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak SL, Murphy RF. Primary cell cultures from murine kidney and heart differ in endosomal pH. J Cell Physiol. 1998;176:216–222. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199807)176:1<216::AID-JCP23>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernizzi G, Sknepnek R, Olvera de la Cruz M. Platonic and Archimedean geometries in multicomponent elastic membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4292–4296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012872108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel HJ, Bonner DM. Acetylornithinase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J Biol Chem. 1956;218:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.