Abstract

To reduce costs in a large tuberculosis household contact cohort study in Lima, Peru, we replaced laboratory-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing with home-based rapid HIV testing. We developed a protocol and training course to prepare staff for the new strategy; these included role-playing for home-based deployment of the Determine® HIV 1/2 Ag/Ac Combo HIV test. Although the rapid HIV test produced more false-positives, the overall cost per participant tested, refusal rate and time to confirmatory HIV testing were lower with the home-based rapid testing strategy compared to the original approach. Rapid testing could be used in similar research or routine care settings.

Keywords: TB, rapid testing, human immunodeficiency virus

Abstract

A Lima, Pérou, nous avons remplacé les tests pour le virus de l’immunodéficience humaine (VIH) exécutés au laboratoire par un test rapide exécuté au domicile afin de réduire les coûts dans une grande étude de cohorte chez les contacts de cas de tuberculose au sein du ménage. Nous avons élaboré un protocole et un cours de formation pour préparer le personnel à cette nouvelle stratégie qui comprend le test Determine® 1/2 Ag/Ac Combo HIV ; ces formations comportaient un jeu de rôle pour l’expansion à domicile. Bien que le test VIH rapide entraîne un plus grand nombre de faux positifs, le coût total par participant testé, le taux de refus et la durée avant un test de confirmation VIH ont été plus faibles avec la stratégie de test rapide exécuté au domicile par comparaison avec l’approche initiale. Le test rapide pourrait être utilisé dans des contextes similaires de recherche ou de soins de routine.

Abstract

Para disminuir los costos en un gran estudio de cohorte sobre contactos intra-domiciliarios de pacientes con tuberculosis en Lima, Perú, reemplazamos la prueba de virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana(VIH) del laboratorio por pruebas rápidas de VIH realizadas en el domicilio. Desarrollamos un protocolo y un entrenamiento para preparar al equipo en esta nueva estrategia, incluyendo el desarrollo de ‘juego de roles’ sobre la implementación de la prueba Determine® VIH 1/2 Ag/Ac Combo en el domicilio de los participantes. Aunque la prueba rápida de VIH produjo más resultados falsos positivos, el costo total por participante evaluado, la tasa de rechazo y el tiempo de la prueba confirmatoria de VIH fueron menores con la estrategia de evaluación basada en el domicilio en comparación con la estrategia original. La prueba rápida podría utilizarse en investigaciones similares o en escenarios rutinarios de atención de salud.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a serious health threat in Peru, with 29 194 new cases in 2011 and an annual incidence of 101 per 100 000 population; 2% of TB patients are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive.1 To better understand the epidemic, we began enrolling household contacts (HHCs) of TB patients in Lima, Peru, into a study cohort observing the bacterial, host and environmental factors associated with TB infection and disease. As part of this study, HHCs were screened both for latent tuberculous infection using the tuberculin skin test and for HIV, as HIV infection increases the risk of progression from latent to active TB.2 Moreover, HIV and TB co-infection drastically worsens each infection,3 and while HIV testing of TB contacts is not routine in Peru, as a risk factor for active TB it needed to be accounted for in our study. Blood samples of HHCs were collected at the contacts’ homes and sent to a laboratory for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay testing. Negative results were delivered to the HHCs 2–4 weeks later, while participants with non-negative results were linked to a Ministry of Health clinic for confirmatory sample extraction and follow-up outside of our study.

ASPECT OF INTEREST: CHANGING HIV TESTING PROCEDURES

Benefits of rapid HIV testing

In August 2011, we replaced laboratory-based HIV testing with home-based rapid HIV testing to reduce study costs. We were enrolling >700 HHC per month and the transportation of staff to HHC homes represented a major cost. With eight separate visits to more than 4000 households necessary to complete the study, eliminating even one study visit would lower costs. Rapid HIV testing was being used in Peru and had been found acceptable in a study of TB cases and their HHCs in Lima.4 We projected that by switching to rapid HIV testing, we could in the majority of cases eliminate transportation and staff costs for returning to deliver negative results and at the same time link HIV-positive participants more quickly to care. Moreover, the rapid test cost 60% less than the laboratory-based test.

Drawbacks of home-based, rapid HIV testing

While home-based rapid testing has been used in high HIV prevalence settings such as South Africa5,6 and Uganda,7 Peru’s HIV epidemic is not generalized (adult prevalence = 0.4% [low-high estimate, 0.3–0.5]8) and HIV testing targets at-risk groups and not TB contacts. As we were implementing rapid testing in the context of a research study, we were unsure of the implications of this change. Would HHCs accept rapid HIV testing in their homes, and would our staff be prepared to conduct them? Furthermore, although the Determine® HIV 1/2 Ag/Ac Combo test* (Alere, Jouy-en-Josas, France) has 100% specificity to HIV-1 and HIV-2,9 and it was selected because it was being used in health clinics among TB patients, how would reactive rapid test results requiring confirmation be explained to the participant? Furthermore, discussion groups conducted with staff revealed biosafety concerns, as testing would be performed in the domiciles of the HHCs.

We developed a training program and procedures in consultation with rapid HIV test counselors from a neighbour organization for the correct use of the rapid test and staff practiced using the rapid test during observed role-play exercises to ensure procedural fidelity. Quality control measures included staff observation by an independent monitor.

The study was reviewed and approved by research ethics committees at the Harvard School of Public Health and Peru’s National Institute of Health. All participants provided voluntary informed consent prior to participation.

DISCUSSION

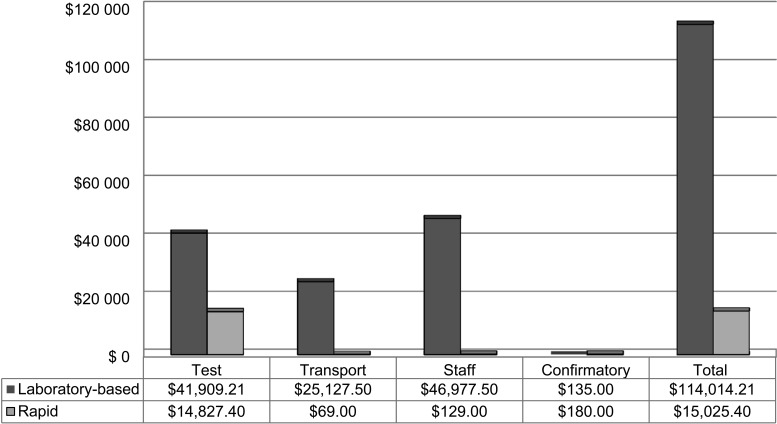

By September 2012, we had offered in-home rapid HIV testing to 6265 HHCs aged ≥2 years, of whom 4361 (69.6%) agreed to the test. The refusal rate for the rapid test was lower than for laboratory-based testing (30.4% vs. 43.31%). Among the 4361 individuals who underwent rapid testing, 14 (0.32%) had initial positive results; of these, 12 accepted confirmatory re-testing and nine were confirmed positive, yielding a positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.75 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.43–0.95). Among the 3974 individuals who underwent laboratory-based testing, 15 (0.38%) had initial positive results of which all 15 were positive on confirmation, yielding a PPV of 100% (95%CI 0.78–1.0; Table). One HHC who tested HIV-positive in the laboratory-based group was found to be in a serodiscordant relationship with an HIV-negative, active TB case. Staff reported no participant barriers to the rapid test acceptance. The estimated cost savings to our study by switching to the rapid test was US$98 988.81, including additional costs for confirmatory testing incurred by the false-positive rapid tests. The Figure compares the actual cost of the 4361 rapid tests with the estimated costs of laboratory-based testing. The average time from the first blood test to the confirmatory test fell from 34 days (median 15, range 6–156) for laboratory-based testing to 30 (median 10, range 1–165) for rapid testing.

TABLE.

In-home rapid vs. laboratory-based HIV testing: offered, refused, performed and positive tests

| HIV tests | In-home rapid test participants enrolled after August 2011 |

Laboratory-based ELISA test participants enrolled before August 2011 |

||||

| Age 2–13 years | Age ≥14 years | Total | Age 2–13 years | Age ≥14 years | Total | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Offered | 1711 (100) | 4554 (100) | 6265 (100) | 1884 (100) | 5130 (100) | 7014 (100) |

| Refused | 976 (57.0) | 928 (20.4) | 1904 (30.4) | 1400 (74.3) | 1640 (32) | 3040 (43.3) |

| Performed | 735 (43.0) | 3626 (79.6) | 4361 (69.6) | 484 (25.7) | 3490 (68) | 3974 (56.7) |

| Positive | 2 (0.27) | 12 (0.33) | 14 (0.32) | 0 | 15 (0.43) | 15 (0.38) |

| Accepted confirmatory testing | 1 | 11 | 12 | — | 15 | 15 |

| Confirmed HIV-positive, n (% of all performed tests)* | 0 | 9 (0.25) | 9 (0.21) | — | 15 (0.43) | 15 (0.38) |

| Positive predictive value, % [95%CI] | 0 | 82 | 75 [0.43–0.95] | — | 100 | 100 [0.78–1.00] |

Using ELISA and indirect immunofluorescence assay.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; CI = confidence interval.

FIGURE.

Cost comparison for performing 4361 HIV tests using in-home rapid testing vs. laboratory-based testing in a research study. The following cost estimates were used: testing (per unit in 2011): laboratory-based ELISA US$9.61, rapid US$3.40, confirmatory US$15; transport (one round trip by taxi from study site to participant’s home) US$5.75; staff time (estimated at 1 h, including travel time) US$10.75. HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

CONCLUSION

Home-based, rapid HIV testing of HHC in a research study achieved considerable cost savings and higher testing rates, but only slightly shortened the time to confirmatory testing compared to laboratory-based testing. Nonetheless, for >99% of the participants, HIV infection was ruled out in minutes rather than weeks. As this was a research study, we did not address the time from testing to final HIV diagnosis; however, faster confirmatory testing should reduce time to receipt of antiretroviral therapy for confirmed positive cases. Likewise, rapid testing of HHC would more quickly identify serodiscordant relationships to avert HIV infection of the partner with active TB while speeding the HHC’s access to isoniazid preventive therapy. Our results were limited by the fact that participants could refuse testing, thereby preventing the generalization of our findings to all Peruvian HHCs. Furthermore, the lower PPV of the rapid test in a low HIV prevalence population resulted in more false-positives compared to laboratory testing; however, this was offset by faster knowledge about HIV status. Home-based rapid HIV testing is not routinely conducted in Peru in any population. This analysis demonstrates that it is feasible and acceptable to TB contacts and that it could be used in both research and practice settings.

Acknowledgments

The work performed and described in this article was supported by U19 AI-076217 ‘Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of MDR/XDR tuberculosis’ and U01 AI057786 ‘Epidemiology of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis’, under the auspices of the US National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Footnotes

At the time the Determine 4th generation test was selected, data on its limitations in detecting acute HIV infection were as yet unknown; we therefore do not consider this aspect of the test in this report. (See Brauer M, De Villiers J C, Mayaphi S H. Evaluation of the Determine fourth generation HIV rapid assay. J Virol Methods 2013; 189: 180–183.)

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2012. WHO/HTM/TB/ 2012.6. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/index.html Accessed April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollock K M, Tam H, Grass L, et al. Comparison of screening strategies to improve the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in the HIV-positive population: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000762. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munawwar A, Singh S. AIDS associated tuberculosis: a catastrophic collision to evade the host immune system. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2012;92:384–387. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson A K, Caldas A, Sebastian J L, et al. Community-based rapid oral human immunodeficiency virus testing for tuberculosis patients in Lima, Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:399–406. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro A E, Variava E, Rakgokong M H, et al. Community-based targeted case finding for tuberculosis and HIV in household contacts of patients with tuberculosis in South Africa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1110–1116. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-1941OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabapathy K, Van den Bergh R, Fidler S, Hayes R, Ford N. Uptake of home-based voluntary HIV testing in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lugada E, Levin J, Abang B, et al. Comparison of home and clinic-based HIV testing among household members of persons taking antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: results from a randomized trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:245–252. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e9e069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2010. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beelaert G, Fransen K. Evaluation of a rapid and simple fourth-generation HIV screening assay for qualitative detection of HIV p24 antigen and/or antibodies to HIV-1 and HIV-2. J Virol Methods. 2010;168:218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]