Abstract

Background

Anxiety has been indicated as one of the main symptoms of the cocaine withdrawal syndrome in human addicts and severe anxiety during withdrawal may potentially contribute to relapse. As alterations in noradrenergic transmission in limbic areas underlie withdrawal symptomatology for many drugs of abuse, the present study sought to determine the effect of cocaine withdrawal on β-adrenergic receptor (β1 and β2) expression in the amygdala.

Methods

Male Sprague Dawley rats were administered intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of cocaine (20 mg/kg) once daily for 14 days. Two days following the last cocaine injection, amygdala brain regions were micro-dissected and processed for Western blot analysis. Results showed that β1–adrenergic receptor, but not β2–adrenergic receptor expression was significantly increased in amygdala extracts of cocaine-withdrawn animals as compared to controls. This finding motivated further studies aimed at determining whether treatment with betaxolol, a highly selective β1–adrenergic receptor antagonist, could ameliorate cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety. In these studies, betaxolol (5 mg/kg via i.p. injection) was administered at 24 and then 44 hours following the final chronic cocaine administration. Anxiety-like behavior was evaluated using the elevated plus maze test approximately 2 hours following the last betaxolol injection. Following behavioral testing, betaxolol effects on β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression were examined by Western blotting in amygdala extracts from rats undergoing cocaine withdrawal.

Results

Animals treated with betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal exhibited a significant attenuation of anxiety-like behavior characterized by increased time spent in the open arms and increased entries into the open arms compared to animals treated with only saline during cocaine withdrawal. In contrast, betaxolol did not produce anxiolytic-like effects in control animals treated chronically with saline. Furthermore, treatment with betaxolol during early cocaine withdrawal significantly decreased β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression in the amygdala to levels comparable to those of control animals.

Conclusions

The present findings suggest that the anxiolytic-like effect of betaxolol on cocaine-induced anxiety may be related to its effect on amygdalar β1-adrenergic receptors that are up-regulated during early phases of drug withdrawal. These data support the efficacy of betaxolol as a potential effective pharmacotherapy in treating cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety during early phases of abstinence.

Keywords: norepinephrine, cocaine, amygdala, anxiety, withdrawal, beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists, betaxolol, western blot, elevated plus maze, rat

Introduction

The cocaine withdrawal syndrome is mainly characterized by depression and anxiety (Gawin and Kleber, 1986; Gawin, 1991; Erb et al., 2006). Severe anxiety, as a component of the affective changes (dysphoria and anhedonia) that occur during withdrawal in human cocaine addicts, may cultivate the repetitive cycle of chronic cocaine abuse and/or motivate relapse to use (Gawin and Kleber, 1986; Koob and Bloom, 1988; Gawin and Ellinwood, 1989; Wise, 1996; Koob et al., 1998; Weiss et al., 2001).

Cocaine use and withdrawal from cocaine causes alterations in norepinephrine transmission in both humans (McDougle et al., 1994) and animals (Harris and Williams, 1992; Baumann et al., 2004). Moreover, an underlying dysregulation in noradrenergic function exists particularly during early discontinuation of cocaine use (typically 1 to 2 days following cessation of use) in both human addicts (McDougle et al., 1994) and drug-treated animals (Baumann et al., 2004), and that this dysregulation is strongly associated with the development of panic anxiety in humans (McDougle et al., 1994) and depressive-like symptoms in animals (Baumann et al., 2004) during this early time period. Furthermore, several studies have reported the manifestation of anxiety-like behavior in animals also during early withdrawal (2 days) from chronic cocaine administration (experimenter delivered; 20 mg/kg/day; 14 days) (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993; Sarnyai et al., 1995; Basso et al., 1999; Paine et al., 2002), while such anxiety-like behavior is absent in animals that undergo no withdrawal period and are evaluated 30 minutes following chronic cocaine administration (20 mg/kg/day; 14 days) (Sarnyai et al., 1995). In addition, Coffey et al. has reported that cocaine withdrawal related-anxiety in humans is also at its peak two days following cessation of cocaine use and is significantly and linearly improved with time (Coffey et al., 2000).

Animal studies have demonstrated that during early or short-term withdrawal (2 days) from chronic cocaine exposure, mRNA (Zhou et al., 2003) and protein (Sarnyai et al., 1995) expression of the stress-related neurotransmitter corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is significantly elevated in the amygdala, a limbic forebrain structure responsible for motivation, emotional behavior and fear. Notably, alterations in amygdalar gene expression do not persist following an extended withdrawal period (10 days) (Zhou et al., 2003). Therefore, these findings suggesting potent activation of amygdalar stress peptide activity following early cocaine withdrawal, have implicated the amygdala as the main candidate mediator in the ‘anxiety-like’ behavior that is observed during the initial phase of cocaine abstinence (Sarnyai, 1998; Zhou et al., 2003). It is known that the amygdala receives noradrenergic innervation from the brainstem nucleus locus coeruleus (Pitkanen, 2000), as well as from other brain regions such as the nucleus of the solitary tract (Clayton and Williams, 2000; Pitkanen, 2000); however, the effect of cocaine withdrawal on amygdalar noradrenergic receptors has not been investigated.

β-adrenergic receptor antagonists, propanolol and atenolol, have both demonstrated efficacy in blocking cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety in rats during early abstinence (2 days) from chronic cocaine administration (20 mg/kg/day, 14 days) (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993) and these effects were demonstrated using the conditioned defensive burying paradigm. Propanolol is a non-selective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist, having an equal affinity for both β1 and β2 –adrenergic receptors, while atenolol has a much greater affinity for β1 (Hardman et al., 2001). Treatment with either of these drugs following chronic cocaine administration blocked the behavioral manifestations of anxiety in animals, such as significantly shorter latencies to begin burying as well as substantial increase in burying duration relative to saline-treated animals, that were seen during early cocaine withdrawal in untreated animals (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993). Data from these studies suggest that β1 and/or β2 -adrenergic receptor activation may play an integral role in the etiology of cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety.

Our initial studies sought to examine β-adrenergic receptor (both β1 and β2) expression in the amygdala of rats following both short (2 days) and intermediate- term (12 days) withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration (20 mg/kg/day, 14 days). Results from these experiments demonstrated a significant and dramatic increase in β1, but not β2 -adrenergic receptor protein expression in the amygdala of rats following only short-term withdrawal. We subsequently tested the hypothesis that treatment with the selective β1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, betaxolol (Mosby, 2006), during early cocaine withdrawal may attenuate cocaine withdrawal-related anxiety-like behavior in rats. To test our hypothesis, we administered betaxolol to animals during early cocaine withdrawal and then evaluated anxiety-like behavior in these animals using the elevated plus maze, a widely used procedure for investigating the anxiogenic effects of drugs in animals (Pellow et al., 1985). The open arms of the maze combine the fear of a novel, brightly-lit open space and the fear of balancing on a narrow, raised platform, while the closed arms have high walls forming a narrow alley that offers protection from potential threats (Dawson and Tricklebank, 1995). This behavioral paradigm was chosen for our studies, as it has been particularly indicated as useful in the elucidating the anxiogenic effects of cocaine in rats (Rogerio and Takahashi, 1992).

Similar to findings of other studies (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993; Sarnyai et al., 1995), animals undergoing 48-hours of withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration displayed a significant increase in anxiety-like behavior, indicated by more time spent in the closed arms and less entries into the open arms, compared to saline control animals. The major finding of our studies was that betaxolol administration in animals during early withdrawal from chronic cocaine exposure produced an anxiolytic-like type of effect in these animals as demonstrated by an increased percentage of time spent in the open arms and increased percentage of open arm entries as compared to animals undergoing cocaine withdrawal without betaxolol treatment. The importance of this result is not just in the abolishment of anxiety-like behavior in these animals, but in the specificity of the anxiolytic-like action of this drug, as treatment with betaxolol did not produce anxiolytic-like effects in animals treated with only chronic saline. Lastly, in these studies we found that betaxolol treatment during early cocaine withdrawal abrogated increases in β1-adrenergic receptor expression levels in the rat amygdala. Taken together, data from these studies provide evidence for the anxiolytic effects of betaxolol during early cocaine withdrawal likely via its effect on β1-adrenergic receptors in the amygdala which are up-regulated during this time period.

Materials and Methods

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN; age 60 days old, 250–274 g) were used in this study. The animal procedures used were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Thomas Jefferson University and conform to National Institutes of Health guidelines. Rats were housed two per cage on a 12-h light schedule (lights on at 7:00 am) in a temperature-controlled (20°C) colony room and allowed ad libitum access to food and water. Rats were allowed to acclimate to the animal housing facility for several days prior to the start of the study. To sufficiently eliminate handling apprehension in the animals by the time they were to undergo behavioral testing, the animals were handled for 5 minutes per day for 5 days prior to the start of drug treatment and then were handled and weighed daily during the course of drug treatment.

Drug Treatment

Cocaine hydrochloride (supplied by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD) was dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride (saline) solution at a concentration of 20 mg/ml, such that experimental and control animals were injected with 0.1 ml/100 g body weight of either cocaine or saline, respectively.

For the no withdrawal and two and 12 day withdrawal experiments, animals were randomly assigned to two treatment groups at the beginning of the study. One half of the animals were administered cocaine once daily at a dosage of 20 mg/kg via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection for 14 days, while the other half of the animals received chronic once daily i.p. injections of saline solution (1 ml/kg) for 14 days. Following the drug treatment, the animals were randomly subdivided into groups based on length of withdrawal that they would undergo. The animals that underwent no withdrawal were euthanized 30 minutes following the last cocaine injection for the purposes of protein immunoblotting experiments. For the two and 12 day withdrawal experiments, the animals received no further injections for either two or 12 days following the drug treatment, respectively. Following the designated withdrawal period, these animals were euthanized for the purposes of protein immunoblotting experiments.

For the betaxolol dose response study, animals were randomly assigned to five different treatment groups at the beginning of the study. Four groups of animals were administered cocaine once daily at a dosage of 20 mg/kg via i.p. injection for 14 days, while the fifth group received chronic once daily i.p. injections of saline solution (1 ml/kg) for 14 days. Subsequent to the 14 day cocaine administration period, three groups of animals received betaxolol hydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 0.9 % sodium chloride at one of three different doses (0.5, 2, or 5 mg/kg). Additionally, another group of animals received only saline (1 ml/kg) via i.p. injection during the withdrawal period. The control animals that received only chronic saline treatment during the drug administration period, also received only saline (1 ml/kg) during the withdrawal period. The first dose of betaxolol was administered 24 hours after the final treatment of chronic cocaine. Another dose of betaxolol was administered at 44 hours following cessation of chronic cocaine administration. Animals were evaluated for anxiety-like behavior on the elevated plus maze approximately 2 hours following their final treatment with either betaxolol or saline.

For the betaxolol administration experiments, animals were randomly assigned to two treatment groups at the beginning of the study. One half of the animals were administered cocaine once daily at a dosage of 20 mg/kg via i.p. injection for 14 days, while the other half of the animals received chronic once daily i.p. injections of saline (1 ml/kg) for 14 days. Subsequent to the 14 day drug administration period, animals were randomly sorted into the four distinct treatment groups based on the treatment they would receive during the 48 hour withdrawal period. The four treatment groups are described in Table 1. As indicated in Table 1, two groups of animals received betaxolol hydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in saline (5 mg/ml) and two groups received only saline (1 ml/kg) via i.p. injection during the withdrawal period. The first dose of betaxolol was administered 24 hours after the final treatment of chronic cocaine or saline. Another dose of betaxolol was administered at 44 hours following cessation of chronic cocaine administration. Animals were evaluated for anxiety-like behavior on the elevated plus maze approximately 2 hours following their final treatment with either betaxolol or saline. Immediately following the elevated plus maze test, a subset of randomly selected animals from the four treatment groups (see Table 1) underwent locomotor testing and then were euthanized for the purposes of Western blotting experimentation.

Table 1.

Drug Treatment Conditions

| Drug Treatment: (Daily Injections; 14 Days) | 24 hrs after Final Drug Treatment | 44 hours after Final Drug Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Saline (1 ml/kg) | Saline (1 ml/kg) | Saline (1 ml/kg) |

| Group 2 | Cocaine (20 mg/kg) | Saline (1 ml/kg) | Saline (1 ml/kg) |

| Group 3 | Saline (1 ml/kg) | Betaxolol (5 mg/kg) | Betaxolol (5 mg/kg) |

| Group 4 | Cocaine (20 mg/kg) | Betaxolol (5 mg/kg) | Betaxolol (5 mg/kg) |

Elevated Plus Maze Test

The elevated plus maze (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA) consists of four equal-sized arms made of black Plexiglas (approximately 50 cm long x 10 cm wide). The maze was elevated 50 cm above the floor. The arms are arranged in a cross, with two opposite arms being enclosed (closed arm; 40 cm high walls) and with the other two arms left open (open arm; 0.5 cm high edges). Each arm is positioned at a 90 degree angle to the adjacent arm. Behavioral testing was conducted in a quiet dimly lit room providing a constant illumination along the two open arms. At the beginning of each test, the animal was placed onto the center of the apparatus facing a closed arm. The behavior of each animal on the elevated plus maze test was video recorded for 5 minutes and later analyzed and scored. The maze was cleaned with water and ethanol between each animal testing session. For each animal, the duration of time spent in the open arms and the number of entries into the open and closed arms was counted and scored over the 5 minute testing session (Pellow et al., 1985). Entry into either the open or closed arms was counted when all four feet entered into one arm (Pellow et al., 1985).

The time spent in the open arms and the number of entries into the open arms are parameters of this behavioral paradigm which have been shown to be increased by effective anxiolytic drugs (Pellow et al., 1985) and decreased by anxiogenic drugs (Basso et al., 1999). Scored data is expressed as a percentage [(open/open + closed) x 100]. Therefore, data is represented as a percentage of time spent in the open arms/total time spent in both open + closed arms ± Standard Error of the Mean (S.E.M.) and as a percentage of the entries into the open arms/total number of entries into both the open and closed arms (± S.E.M). Data was analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post-hoc Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Locomotor Activity Test

Locomotor activity was analyzed in a subset of randomly selected animals from the four drug treatment groups (see Table 1) immediately following behavioral testing on the elevated plus maze. Animals were placed into their home cages, which were inserted into a Home Cage Video Tracking System (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). This system was equipped with a sound attenuating cubicle, video tracking interface, a computer interface card, and Activity Monitor 5 software (Med Associates). The locomotor activity measurements of the animals were recorded by a computer interface for 10 minutes. Two different variables were evaluated: (1) distance traveled and (2) velocity of ambulation. For each animal, the mean of the distance traveled was calculated from the total distance traveled in one minute increments over the ten minute testing session. The final reported value of distance traveled reflects the mean distance (centimeters) traveled per minute of the testing session. Also, the mean of the average velocity for each animal was calculated from the summation of the average velocities recorded in one minute increments over the ten minute testing session. Thus, the final reported value of average velocity of ambulation reflects the mean average velocity (in centimeters per second) per minute of the testing session. Data of the mean distances traveled and the average velocities of ambulation, key indices of locomotor activity, were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Western Blot Analysis

Immediately following either the designated withdrawal periods or exposure to the elevated plus maze and the locomotor activity tests, animals were briefly exposed to isoflurane and then euthanized by decapitation. Brain tissue was rapidly removed on ice from each animal and using a trephine and razor blades, the amygdala and frontal cortex brain regions were micro-dissected from each. The amygdala and frontal cortex regions were separately homogenized with a pestle and extracted in RadioImmunoPrecipitation Assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) on ice for 20 min. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 12 min at 4 ºC. Supernatants were diluted with an equal volume of Novex® 2X Tris-Glycine Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing dithiothreitol (DTT; Sigma). Protein concentrations of the supernatants were quantified using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were separated on 4–12% Tris-Glycine polyacrylamide gels and then electrophoretically transferred to Immobilon-P PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were incubated in β1-adrenergic receptor (1:500; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or β2-adrenergic receptor (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) primary antibodies (a minimum of two hours) and then secondary antibodies for 30 minutes in order to probe for the presence of proteins using a Western blotting detection system (Western Breeze Chemilluminescent Kit, Invitrogen). Following incubation in a chemiluminescent substrate (Western Breeze Chemiluminescent Kit, Invitrogen), blots were exposed to X-OMAT AR film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) for different lengths of time to optimize exposures. β1 and/or β2 -adrenergic receptor protein expression was readily detected by immunoblotting in rat amygdala and/or frontal cortex extracts. β1-adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity was visualized as a single band that migrates at approximately 64 kDa, whereas β2-adrenergic receptor migrates at 46.5 kDa. Blots were incubated in stripping buffer (Restore Stripping Buffer, Pierce) to disrupt previous antibody-antigen interactions and then re-probed with β-actin (1:5000; 1 hour incubation, Sigma) to ensure proper protein loading. The density of each band was quantified using Un-Scan-It blot analysis software (Silk Scientific Inc., Orem, Utah). β1 and/or β2 -adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity was normalized to β-actin immunoreactivity on each respective blot. Depending on the experiment, western blotting data was analyzed by either unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison test. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

β1–adrenergic Receptor Expression is Increased Following Early (2 Day) Withdrawal from Chronic Cocaine Administration

Statistical analysis showed that amygdala extracts from rats that were euthanized following chronic cocaine administration with no withdrawal period exhibited no significant difference in the expression of β1 (unpaired t-test, p > 0.05, n = 5/group) or β2 -adrenergic receptors (unpaired t-test, p > 0.05, n = 5/group) compared to saline-treated animals (Figure 1). Conversely, amygdala extracts from rats that underwent short-term withdrawal (2 days) from chronic (14 days) cocaine administration exhibited a significant increase (unpaired t-test; p < 0.05; n = 5/group) in the expression of β1-adrenergic receptor compared to saline-treated animals (Figure 1). However, no significant difference (unpaired t-test; p > 0.05; n = 5/group) was found in expression levels of β2-adrenergic receptor between cocaine withdrawn and control animals (Figure 1). Animals that underwent 12 days of withdrawal following chronic cocaine administration exhibited no significant change in amygdala protein expression levels of either β1 (unpaired t-test; p > 0.05; n = 5/group) or β2-adrenergic receptors (unpaired t-test; p > 0.05; n = 5/group) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. β1–adrenergic receptor expression is increased following early (2 day) withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration.

Amygdala extracts from rats that were euthanized following chronic cocaine administration (20 mg/kg i.p. for 14 days) with no withdrawal period exhibited no significant difference in the expression of either β1 or β2 -adrenergic receptors compared to saline-treated animals. Following 2 day withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration, β1–adrenergic receptor expression was significantly increased (p < 0.05), while β2-adrenergic receptor expression was unchanged in rat amygdala extracts. Animals that underwent 12 days of withdrawal following chronic cocaine administration exhibited no significant change in amygdala protein expression levels of either β1 or β2 -adrenergic receptors.

Effect of Varying Doses of Betaxolol on Anxiety-Like Behavior During Early Abstinence from Chronic Cocaine Administration

Using the elevated plus maze behavioral test, the effect of three different betaxolol doses (0.5, 2, and 5 mg/kg administered 24 and then 44 hours following 14 day chronic cocaine administration) was evaluated on anxiety-like behavior in rats. Data is represented as a percentage of time spent in the open arms divided by the total time spent in both the open and closed arms (± S.E.M.; Figure 2A) and as a percentage of the entries into the open arms divided by the total number of entries into both the open and closed arms (± S.E.M.; Figure 2B). Behavioral data from animals was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison test. Statistical analyses showed that there were significant behavioral differences among groups (n = 5/treatment group) regarding both the percentage of time spent in the open arms (p = 0.0015; F(4,20) = 6.606) and the percentage of entries into the open arms (p = 0.0033; F(4,20) = 5.632). Animals undergoing short-term cocaine withdrawal exhibited appreciable anxiety-like behavior compared to control animals. This was demonstrated on the elevated plus maze as the percentage of time spent in the open arms and the percentage of entries into the open arms of the maze was significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in animals receiving only saline treatment during cocaine withdrawal, compared to chronic saline-treated control animals (Figures 2A and 2B). Betaxolol administered at 0.5 mg/kg and 2.0 mg/kg dosages during cocaine withdrawal did not appreciably attenuate anxiety-like behavior in cocaine-withdrawn animals. There was no significant difference demonstrated in the percent of time spent in the open arms (Figure 2A; p > 0.05) or percent of open arm entries (Figure 2B; p > 0.05) between animals treated with chronic cocaine followed by either the 0.5 mg/kg or 2.0 mg/kg dosages of betaxolol compared with animals that received only saline during cocaine withdrawal. Conversely, the 5 mg/kg dosage of betaxolol administered 24 and 44 hours following chronic cocaine treatment significantly ameliorated cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behavior in the animals, as 5 mg/kg betaxolol-treated rats demonstrated increased open arm exploration time (Figure 2A; p < 0.05) and increased entries into the open arm (Figure 2B; p < 0.05) of the elevated plus maze as compared to cocaine withdrawn animals. Furthermore, the animals that received the 5 mg/kg dosages of betaxolol also demonstrated similar open arm exploration time and entries into the open arms of the maze as control animals treated only with saline. This was confirmed as a lack of significant difference between open arm exploration time (Figure 2A; p > 0.05) and open arm entries (Figure 2B; p > 0.05) between these two groups of animals.

Figure 2. Dose response of betaxolol administration on cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behavior measured by the elevated plus maze.

Data is represented as (A) the mean percentage of time spent in the open arms/total time spent in both open + closed arms (± S.E.M) and (B) the mean percentage of the entries into the open arms/total number of entries into both the open and closed arms (± S.E.M.). Prior to testing, rats were administered chronic cocaine (20 mg/kg i.p. daily for 14 days) followed by one of three different betaxolol treatments (0.5, 2.0 or 5.0 mg/kg i.p.) at 24 and 44 hours following the last cocaine injection. Control animals received either chronic i.p. injections of cocaine (20 mg/kg) or saline (1 ml/kg) for 14 days followed by administration of saline (1 ml/kg) at 24 and 44 hours during the withdrawal phase. (*p < 0.05)

Betaxolol Diminishes Anxiety-Like Behavior During Early Abstinence from Chronic Cocaine Administration

Statistical analyses showed that there were significant behavioral differences among groups of animals (see Table 1; n = 15/treatment group) regarding both the percentage of time spent in the open arms (p = 0.007; F(3,56) = 4.471; Figure 3A) and the percentage of entries into the open arms (p < 0.0001; F(3,56) = 8.899; Figure 3B). Animals undergoing short-term cocaine withdrawal exhibited appreciable anxiety-like behavior compared to control animals. This was demonstrated on the elevated plus maze as the percentage of time spent in the open arms was significantly decreased by 63% (p < 0.05) in animals receiving only saline treatment during cocaine withdrawal (Group 2; see Table 1), compared to chronic saline-treated control animals (Group 1). In addition, the percentage of entries into the open arms of the maze was also significantly decreased by 62% (p < 0.01) in these cocaine-withdrawn animals (Group 2) compared to saline control animals (Group 1). Animals receiving only saline treatment during cocaine withdrawal (Group 2) also demonstrated a 60% decrease (p < 0.05) in the percent of open arm exploration time and a 57% decrease (p < 0.01) in the percent of open arm entries compared to animals that received chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (Group 3).

Figure 3. Betaxolol diminishes anxiety-like behavior during early abstinence from chronic cocaine administration in rats.

Data is represented as (A) the mean percentage of time spent in the open arms/total time spent in both open + closed arms (± S.E.M); (B) the mean percentage of the entries into the open arms/total number of entries into both the open and closed arms (± S.E.M.); and (C) the mean number of closed arm entries (± S.E.M). Prior to testing, rats were administered either chronic i.p. injections of cocaine (20 mg/kg) or saline (1 ml/kg) for 14 days followed by either i.p. betaxolol (5 mg/kg) or saline (1 ml/kg) at 24 and 44 hours following the last drug injection. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001)

The percent of time spent in the open arms of the maze was substantially and significantly increased by 218% (p < 0.01) in animals treated with betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal (Group 4) compared to animals that underwent cocaine withdrawal without betaxolol treatment (Group 2). Additionally, the percentage of open arm entries was also significantly increased by 227% (p < 0.001) in animals treated with betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal (Group 4) compared to animals not administered betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal (Group 2).

Furthermore, animals treated with betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal (Group 4) demonstrated indices of behavior on the elevated plus maze similar to those of both, animals treated with chronic saline with no betaxolol treatment (Group 1), and animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (Group 3). This was shown by a lack of significant difference in the percent of time spent in the open arms (p > 0.05) and the percent of open arm entries (p > 0.05) between animals receiving chronic saline with no betaxolol (Group 1) and animals that received betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal (Group 4). Additionally, there was no significant difference demonstrated in the percent of time spent in the open arms (p > 0.05) or percent of open arm entries (p > 0.05) between animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (Group 3) compared with animals that received betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal (Group 4).

Importantly, treatment with betaxolol alone did not produce anxiogenic or anxiolytic –like behavior in animals treated with chronic saline. There was no significant difference in percent of time spent in the open arms (p > 0.05) or the percent of open arm entries (p > 0.05) between animals treated with chronic saline and no betaxolol (Group 1) and animals that received chronic saline and then betaxolol (Group 3).

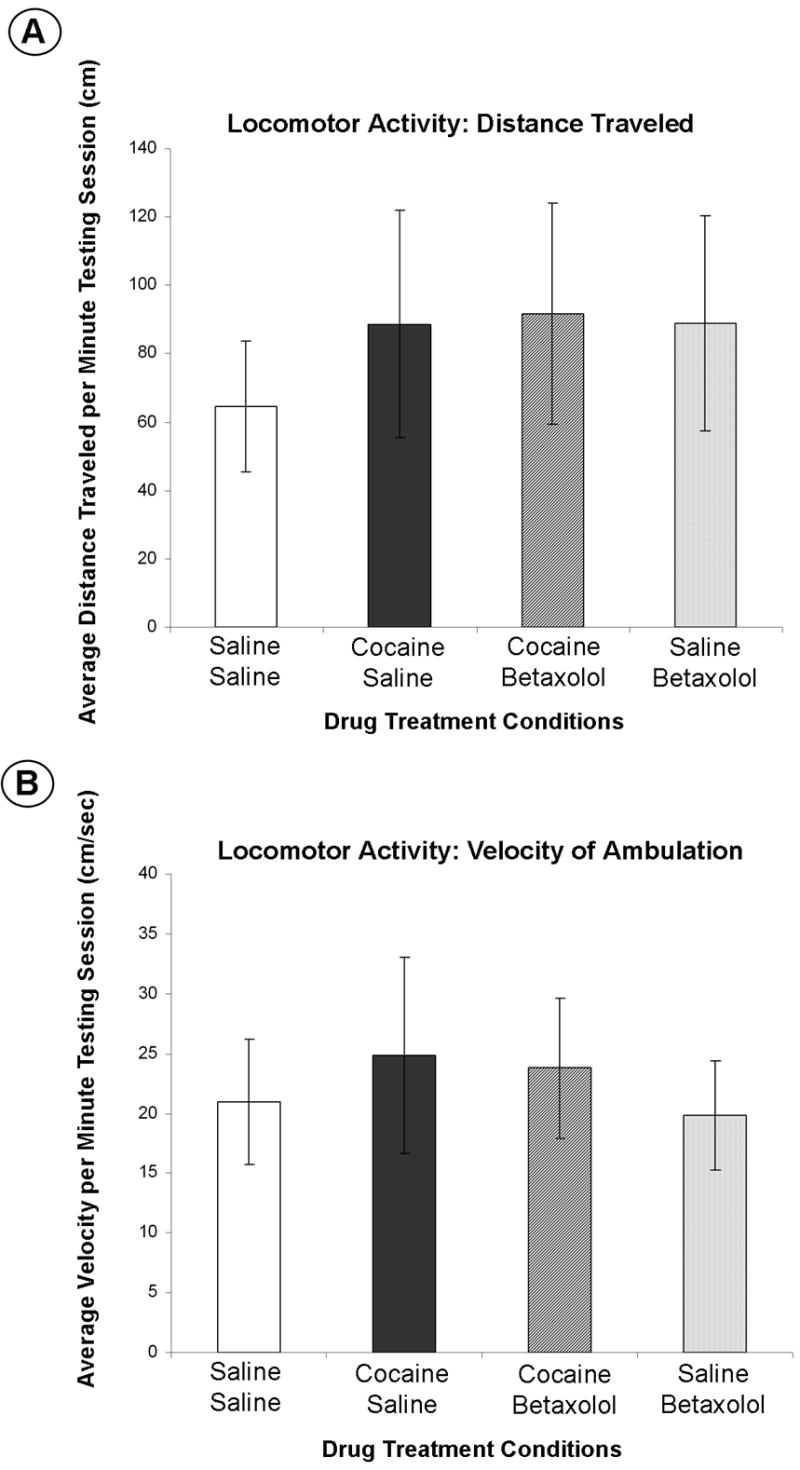

Effect of Betaxolol Treatment on Locomotor Activity During Early Abstinence from Chronic Cocaine Administration

As shown in Figure 3C, one-way ANOVA statistical analyses demonstrated no significant difference between groups (see Table 1; n = 15/treatment group) in the mean number of closed arm entries on the elevated plus maze (p = 0.6073; F(3,56) = 0.6164). Additionally, ANOVA statistical analyses showed no significant difference between groups (see Table 1; n = 5/treatment group) in either mean ambulatory distance traveled (p = 0.9074; F(3,16) = 0.1814; Figure 4A) or average velocity of ambulation (p = 0.9319; F(3,16) = 0.1442; Figure 4B) over the testing session, therefore, it was not necessary to perform post-hoc group comparisons on this data. However, it is essential to note that there was no significant difference found in the mean distance traveled between animals undergoing cocaine withdrawal (Group 2; see Table 1) and saline control animals (Group 1), nor was there a significant difference between average velocity of ambulation of these animals (Group 2 vs. Group 1). Most importantly, there was also no significant difference found between groups of animals that underwent cocaine withdrawal with no betaxolol treatment (Group 2) and animals that were treated with betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal (Group 4) in either mean distance traveled or average velocity of ambulation.

Figure 4. Anxiolytic-like effects of betaxolol demonstrated during early withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration are not attributable to alterations in ambulatory activity.

Data is represented as (A) the mean distance traveled per minute of the testing session (± S.E.M) and (B) the mean average velocity (in centimeters per second) per minute of the testing session (± S.E.M). For each animal, the mean of the distance traveled was calculated from the total distance traveled over the ten minute testing session that was reported in one minute increments. The mean of the average velocity for each animal was calculated from the summation of the average velocities recorded in one minute increments over the ten minute testing session..

Betaxolol Treatment During Early Cocaine Withdrawal Abrogates Increases in β1–Adrenergic Receptor Protein Expression in the Amygdala

An one-way ANOVA analysis demonstrated a significant difference among treatment groups (see Table 1; n = 5/treatment group) in β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression in the amygdala extracts (p = 0.0248; F(3,16) = 4.086) and post-hoc comparison tests among these groups revealed the differences. Conversely, ANOVA analysis revealed no statistically significant difference among groups (see Table 1; n = 5/treatment group) in β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression in the frontal cortex extracts (p = 0.6805; F(3,16) = 0.5108), therefore, post-hoc pair-wise comparison tests were not performed between these groups. Amygdala extracts from animals undergoing cocaine withdrawal with no betaxolol treatment (Group 2) exhibited a significant 48% increase (p < 0.05) in β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression compared to saline control animals (Group 1; Figure 5). Likewise, β1-adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity was significantly greater by 32% (p < 0.05) in cocaine withdrawn animals (Group 2) compared to animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (Group 3; Figure 5). However, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression levels between animals treated with chronic saline and no betaxolol (Group 1) and animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (Group 3; Figure 5).

Figure 5. Betaxolol treatment during early cocaine withdrawal decreases β1–adrenergic receptor protein expression in the amygdala to levels comparable to that of control animals.

β1-adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity was evaluated in amygdala and frontal cortex extracts from animals that were administered either chronic i.p. injections of cocaine (20 mg/kg) or saline (1 ml/kg) for 14 days followed by either i.p. betaxolol (5 mg/kg) or saline (1 ml/kg) at 24 and 44 hours following the last drug injection. β1-adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity in the amygdala of experimental animals is expressed as a percentage of the control mean when the control equals 100. Significant differences are indicated: *, significantly different from saline control animals (p < 0.05) and #, significantly different than cocaine control animals.

Importantly, betaxolol administration had a significant effect on β1-adrenergic receptor expression in the amygdala of animals that underwent cocaine withdrawal. Specifically, amygdala extracts from those animals (Group 4) displayed a significant 29% decrease (p < 0.05) in β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression compared to cocaine administered animals that did not receive betaxolol treatment during withdrawal (Group 2; Figure 5). Also of importance, amygdala extracts from animals treated with betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal (Group 4) exhibited similar levels of β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression as animals treated with chronic saline and no betaxolol treatment (Group 1; p > 0.05), and also animals treated with chronic saline followed by betaxolol treatment (Group 3; p > 0.05; Figure 5).

Discussion

The first major result of these studies is that β1-adrenergic receptor expression in the amygdala is unchanged immediately following chronic cocaine administration, but is significantly increased during early withdrawal from cocaine. Moreover, β1-adrenergic receptor expression in the amygdala returns to levels comparable to that of control animals following an intermediate-term withdrawal period. This data is compelling as it has been previously demonstrated that cocaine withdrawal-related symptomatology in humans is highest during early abstinence from cocaine use and gradually decreases during protracted abstinence in both inpatient and outpatient settings (Weddington et al., 1990; Satel et al., 1991; Coffey et al., 2000).

It is well established that the amygdala, a forebrain limbic region, is responsible for fear recognition (Davis, 2000; Charney, 2003) and mediating anxiety (Davis, 1992; Bremner et al., 1996; Tanaka et al., 2000; Charney, 2003) in humans and animals. Additionally, the amygdala is potently activated following administration and withdrawal from various drugs of abuse, including cocaine (Zhou et al., 2003; Pollandt et al., 2006), morphine (Maj et al., 2003; Watanabe et al., 2003b) and alcohol (Koob, 1999). The amygdala receives robust noradrenergic innervation (Clayton and Williams, 2000; Pitkanen, 2000) and previous studies have shown that dysregulation of the noradrenergic system may accompany long-term cocaine exposure (McDougle et al., 1994). Central noradrenergic activation specifically in the amygdala plays a crucial role in stress-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking in rats, as blockading the amygdala with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists abolishes stress, but not cocaine-induced drug-seeking in rats (Leri et al., 2002). This phenomenon can likely be explained by altered noradrenergic tone, which has been demonstrated to occur during cocaine withdrawal in humans (McDougle et al., 1994), and its concomitant changes that may occur in the regulation and availability of noradrenergic receptors. However, until now, the effect of cocaine withdrawal on noradrenergic receptor expression in the amygdala has been poorly understood.

As cocaine inhibits the re-uptake of synaptic norepinephrine by binding with high affinity to the norepinephrine transporter (Ritz et al., 1990), thus prolonging noradrenergic neurotransmission (Hadfield, 1995), it is tempting to speculate that alterations would exist in noradrenergic receptor regulation during chronic cocaine use and cocaine withdrawal. Indeed, repeated administration of cocaine up-regulates the norepinephrine transporter in limbic regions (Macey et al., 2003; Beveridge et al., 2005), suggesting the hypothesis that the presence of additional norepinephrine transporters may cause a transient depletion in synaptic norepinephrine and, as a result, post-synaptic β1-adrenergic receptors may be forced to up-regulate as a compensatory mechanism during this time period.

Behavioral studies in rats using the defensive burying paradigm have shown that treatment with either propanolol or atenolol during early cocaine withdrawal block withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behavior (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993). Although this study demonstrated that β-adrenergic receptor antagonists may be potentially effective in treating cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety during early withdrawal, the efficacy of those drugs in attenuating anxiety-like behavior was not directly attributed to a central nervous system effect (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993). Instead, the authors proposed that since propanolol, an antagonist of both β1 and β2 -adrenergic receptors, is also capable of binding serotonin receptors, and atenolol enters the brain in only limited amounts, that these drugs may be producing their anxiolytic-like effects by blocking peripheral β1-adrenergic receptors (Harris and Aston-Jones, 1993). To circumvent the caveat that the effects of the β1-adrenergic receptor antagonist may be acting through peripheral receptors, we selected betaxolol, out of the family of β1-antagonists, for use in these studies since betaxolol readily crosses the blood brain barrier (Swartz, 1998) and is classified as highly selective for β1-adrenegic receptors (Mosby, 2006). Betaxolol has also previously demonstrated therapeutic effects in reducing anxiety in patients with persistent anxiety disorders (Swartz, 1998). Additionally, in order to further examine the central nervous system effect of betaxolol treatment during cocaine withdrawal, we examined levels of β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression in the amygdala of rats immediately following the withdrawal period.

The experimental dose of betaxolol administered (5 mg/kg) in these studies was based on previous studies (Watanabe et al., 2003a) and on our dose response experiments (Figure 2). Similar to previous studies (Sarnyai et al., 1995), we observed an anxiogenic effect of cocaine withdrawal on animal behavior in the elevated plus maze following two days of withdrawal. Therefore, using the elevated plus maze behavioral test, we tested the effect of three different betaxolol doses (0.5, 2, and 5 mg/kg administered 24 and then 44 hours following 14 day chronic cocaine administration) on anxiety-like behavior in rats. Data from these studies demonstrated that neither the 0.5 mg/kg or 2 mg/kg dosages administered 24 and 44 hours following chronic cocaine treatment was sufficient to significantly diminish cocaine withdrawal induced anxiety-like behavior in the animals. However, cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behavior was significantly attenuated in betaxolol-treated rats (5 mg/kg, i.p. at 24 h and 44 h following chronic cocaine treatment) as indicated by increased open arm exploration time and increased entries into the open arm of the elevated plus maze as compared to cocaine-withdrawn saline-treated animals. Therefore, the 5 mg/kg dose and regimen of betaxolol was chosen for use in the present study. Betaxolol was administered twice during the course of withdrawal as opposed to just once because sudden discontinuation of beta-blocker type of drugs, such as betaxolol, can sometimes lead to rebound hyperactivity of β-adrenergic receptors (Lopez-Sendon et al., 2004). This phenomenon, however, occurs much less with betaxolol because of its long half-life (in humans), as compared with other beta-blocker drugs (Swartz, 1998). Although the exact half-life of betaxolol in rats is unknown, our dose response studies also indicated that a single dose of betaxolol administered during the two day withdrawal period was not sufficient to abolish anxiety-like behavior in cocaine withdrawn animals (data not shown). Specifically, our studies demonstrated that there was no significant difference between open arm exploration time and the number of open arm entries between cocaine withdrawn animals and animals that received only a single dose of betaxolol at 5 mg/kg at one time-point during the two day withdrawal period.

The major finding of our studies was that betaxolol administration in animals during early withdrawal from chronic cocaine exposure produced an anxiolytic-like type of effect in these animals as demonstrated by an increased percentage of time spent in the open arms and increased percentage of open arm entries as compared to animals undergoing cocaine withdrawal without betaxolol treatment. The importance of this result is not just in the abolishment of anxiety-like behavior in these animals, but in the specificity of the anxiolytic-like action of this drug. Treatment with betaxolol did not produce anxiolytic-like effects in animals treated with only chronic saline, providing evidence that the efficacy of this drug in producing anxiolysis during early cocaine withdrawal is potentially related to its effect on β1-adrenergic receptors in the amygdala which are up-regulated during this time period.

Subsequent to the elevated plus maze experiments, we performed locomotor activity testing in a subset of animals in order to evaluate if betaxolol administration or cocaine withdrawal itself altered ambulatory behavior, which could contribute to the behavioral changes observed on the elevated plus maze (Dawson and Tricklebank, 1995). Following the elevated plus maze testing session, the animals were returned to their home cages and allowed to acclimate to their home environments for approximately one hour. The animals’ home cages were moved into a sound-attenuated cubicle containing a video tracking system, and locomotor activity was recorded and evaluated by a computer interface for ten minutes. Data from the locomotor activity studies demonstrated that animals undergoing cocaine withdrawal displayed no significant difference in values of ambulation compared to saline control animals indicating that the anxiety-like behavior that was demonstrated in these cocaine withdrawn animals is not attributable to alterations in locomotor activity. Importantly, our locomotor activity studies also established that treatment with betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal did not significantly alter the distance the animals traveled during the locomotor test or the velocity of movement of the animals compared to saline control animals. As an additional measure of the ambulatory activity of the animals, the number of closed arm entries on the elevated plus maze were also recorded for each group of animals. Similar to the locomotor activity testing data, no significant difference was observed between treatment groups. Hence, from these experiments we concluded that the amelioration of anxiety-like behavior on the elevated plus maze that is seen in animals treated with betaxolol during cocaine withdrawal is due to the anxiolytic-like effects of the drug and cannot be attributed to alterations in locomotor activity.

The final key finding of our studies was that betaxolol treatment during cocaine withdrawal abrogated the increase in β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression in the amygdala as revealed by immunoblotting. Moreover, β1-adrenergic receptor levels were found to be similar between animals treated chronically with saline and no betaxolol, animals treated with saline and then betaxolol, and animals treated with cocaine and then betaxolol. Additionally, we found no significant difference in β1-adrenergic receptor protein expression in the frontal cortex region regardless of cocaine or betaxolol exposure in comparison to control animals. These findings further suggest that cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety is likely a limbic-mediated phenomenon. Taken together, this data provides additional evidence in support of our hypothesis that the anxiolytic-like effects of betaxolol are likely mediated by its effects on β1-adrenergic receptors in the amygdala that are up-regulated during early cocaine withdrawal, but are blocked following betaxolol treatment. Future studies are aimed at evaluating the effect of intracranial microinfusions of betaxolol into the amygdala during early cocaine withdrawal on cocaine withdrawal-related anxiety-like behavior in rats.

There are gaps in the literature as to the subcellular localization of β1-adrenergic receptors in the amygdala and little is known regarding their implicit function. However, recent studies from our laboratory (Van Bockstaele et al., 2006) suggest that β1-adrenergic receptors are frequently localized to cells containing corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), the stress and anxiety-related peptide neurotransmitter, of which gene expression is substantially increased in the amygdala also during early cocaine withdrawal (Maj et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2003). Interestingly, similar to β1-adrenergic receptor expression levels returning to that of control levels following intermediate-term withdrawal, increases in CRF gene expression in the amygdala are also abolished during this time period (Zhou et al., 2003). The central nucleus of the amygdala (CNA), specifically, is enriched with a dense population of CRF-containing neurons (Swanson et al., 1983). Alterations in CRF gene expression in the CNA have been linked with mediating anxiogenic states that occur during withdrawal from multiple drugs of abuse, including cocaine (Zhou et al., 2003), morphine (Maj et al., 2003), and alcohol (Hwang et al., 2004; Lack et al., 2005).

The β1-adrenergic receptor is known to be coupled to Gs (stimulatory G-protein), such that stimulation of this receptor increases intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels via a direct activation of adenylate cyclase (Schultz and Daly, 1973); and we predict that this cell signaling cascade eventually culminates in increases in CRF gene expression. Therefore, our future studies are aimed at elucidating the effect of betaxolol treatment during cocaine withdrawal on CRF gene expression in the amygdala of rats, thereby unmasking the interplay between the regulation of β1-adrenergic receptor expression and the expression of this highly regulated neurotransmitter, CRF, a substrate that may underlie cocaine-withdrawal related anxiety.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated the ability of betaxolol to diminish anxiety-like behavior in rats undergoing early withdrawal from chronic cocaine administration. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the anxiolytic-like effect of betaxolol on cocaine-induced anxiety may be related to its effect on amygdalar β1-adrenergic receptors that are up-regulated during early phases of drug withdrawal. These data support the efficacy of betaxolol as a potential effective pharmacotherapy in treating cocaine withdrawal-induced anxiety during early phases of abstinence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Predoctoral Fellowship, NIH, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F31DA019311) to C.R. and DA009082 and DA 15395 to E.V.B. The authors would like to thank Ronaldo Magtoto and Kristen Smith for technical assistance.

Grant support: This work was supported by a Predoctoral Fellowship, NIH, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F31–DA019311) to C.R. and DA009082 and DA15395 to E.V.B.

Abbreviations

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- CRF

corticotropin-releasing factor

- CNA

central nucleus of the amygdale

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Basso AM, Spina M, Rivier J, Vale W, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist attenuates the 'anxiogenic-like' effect in the defensive burying paradigm but not in the elevated plus-maze following chronic cocaine in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;145:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s002130051028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Milchanowski AB, Rothman RB. Evidence for alterations in alpha2-adrenergic receptor sensitivity in rats exposed to repeated cocaine administration. Neuroscience. 2004;125:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge TJ, Smith HR, Nader MA, Porrino LJ. Effects of chronic cocaine self-administration on norepinephrine transporters in the nonhuman primate brain. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005 doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Charney DS. Noradrenergic mechanisms in stress and anxiety: I. Preclinical studies. Synapse. 1996;23:28–38. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199605)23:1<28::AID-SYN4>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charney DS. Neuroanatomical circuits modulating fear and anxiety behaviors. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2003:38–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s417.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EC, Williams CL. Adrenergic activation of the nucleus tractus solitarius potentiates amygdala norepinephrine release and enhances retention performance in emotionally arousing and spatial memory tasks. Behav Brain Res. 2000;112:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Dansky BS, Carrigan MH, Brady KT. Acute and protracted cocaine abstinence in an outpatient population: a prospective study of mood, sleep and withdrawal symptoms. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1992;15:353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Chapter 6: The role of the amygdala in conditioned and unconditioned fear and anxiety. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The Amygdala: A Functional Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 213–287. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson GR, Tricklebank MD. Use of the elevated plus maze in the search for novel anxiolytic agents. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88973-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S, Kayyali H, Romero K. A study of the lasting effects of cocaine pre-exposure on anxiety-like behaviors under baseline conditions and in response to central injections of corticotropin-releasing factor. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH. Cocaine addiction: psychology and neurophysiology. Science. 1991;251:1580–1586. doi: 10.1126/science.2011738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH, Ellinwood EH., Jr Cocaine dependence. Annu Rev Med. 1989;40:149–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.40.020189.001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH, Kleber HD. Abstinence symptomatology and psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abusers. Clinical observations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:107–113. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800020013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield MG. Cocaine. Selective regional effects on central monoamines. Mol Neurobiol. 1995;11:47–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02740683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Goodman Gilman A, editors. McGraw-Hill: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Aston-Jones G. Beta-adrenergic antagonists attenuate withdrawal anxiety in cocaine- and morphine-dependent rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;113:131–136. doi: 10.1007/BF02244345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Williams JT. Sensitization of locus ceruleus neurons during withdrawal from chronic stimulants and antidepressants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:476–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang BH, Stewart R, Zhang JK, Lumeng L, Li TK. Corticotropin-releasing factor gene expression is down-regulated in the central nucleus of the amygdala of alcohol-preferring rats which exhibit high anxiety: a comparison between rat lines selectively bred for high and low alcohol preference. Brain Res. 2004;1026:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. The role of the striatopallidal and extended amygdala systems in drug addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:445–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Bloom FE. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence. Science. 1988;242:715–723. doi: 10.1126/science.2903550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron. 1998;21:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lack AK, Floyd DW, McCool BA. Chronic ethanol ingestion modulates proanxiety factors expressed in rat central amygdala. Alcohol. 2005;36:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Flores J, Rodaros D, Stewart J. Blockade of stress-induced but not cocaine-induced reinstatement by infusion of noradrenergic antagonists into the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis or the central nucleus of the amygdala. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5713–5718. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05713.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Sendon J, Swedberg K, McMurray J, Tamargo J, Maggioni AP, Dargie H, Tendera M, Waagstein F, Kjekshus J, Lechat P, Torp-Pedersen C. Expert consensus document on beta-adrenergic receptor blockers. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1341–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macey DJ, Smith HR, Nader MA, Porrino LJ. Chronic cocaine self-administration upregulates the norepinephrine transporter and alters functional activity in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of the rhesus monkey. J Neurosci. 2003;23:12–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00012.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maj M, Turchan J, Smialowska M, Przewlocka B. Morphine and cocaine influence on CRF biosynthesis in the rat central nucleus of amygdala. Neuropeptides. 2003;37:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(03)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle CJ, Black JE, Malison RT, Zimmermann RC, Kosten TR, Heninger GR, Price LH. Noradrenergic dysregulation during discontinuation of cocaine use in addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:713–719. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950090045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosby. Mosby's Drug Consult. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Paine TA, Jackman SL, Olmstead MC. Cocaine-induced anxiety: alleviation by diazepam, but not buspirone, dimenhydrinate or diphenhydramine. Behav Pharmacol. 2002;13:511–523. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellow S, Chopin P, File SE, Briley M. Validation of open:closed arm entries in an elevated plus-maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1985;14:149–167. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(85)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A. Chapter 2: Connectivity of the rat amygdaloid complex. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The Amygdala: A Functional Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pollandt S, Liu J, Orozco-Cabal L, Grigoriadis DE, Vale WW, Gallagher JP, Shinnick-Gallagher P. Cocaine withdrawal enhances long-term potentiation induced by corticotropin-releasing factor at central amygdala glutamatergic synapses via CRF, NMDA receptors and PKA. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1733–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Cone EJ, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine inhibition of ligand binding at dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin transporters: a structure-activity study. Life Sci. 1990;46:635–645. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90132-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogerio R, Takahashi RN. Anxiogenic propeFties of cocaine in the rat evaluated with the elevated plus-maze. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;43:631–633. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90203-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnyai Z. Neurobiology of stress and cocaine addiction. Studies on corticotropin-releasing factor in rats, monkeys, and humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;851:371–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnyai Z, Biro E, Gardi J, Vecsernyes M, Julesz J, Telegdy G. Brain corticotropin-releasing factor mediates 'anxiety-like' behavior induced by cocaine withdrawal in rats. Brain Res. 1995;675:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00043-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satel SL, Price LH, Palumbo JM, McDougle CJ, Krystal JH, Gawin F, Charney DS, Heninger GR, Kleber HD. Clinical phenomenology and neurobiology of cocaine abstinence: a prospective inpatient study. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1712–1716. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.12.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Daly JW. Accumulation of cyclic adenosine 3', 5'-monophosphate in cerebral cortical slices from rat and mouse: stimulatory effect of alpha- and beta-adrenergic agents and adenosine. J Neurochem. 1973;21:1319–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb07585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE, Rivier J, Vale WW. Organization of ovine corticotropin-releasing factor immunoreactive cells and fibers in the rat brain: an immunohistochemical study. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;36:165–186. doi: 10.1159/000123454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz CM. Betaxolol in anxiety disorders. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1998;10:9–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1026146528290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Yoshida M, Emoto H, Ishii H. Noradrenaline systems in the hypothalamus, amygdala and locus coeruleus are involved in the provocation of anxiety: basic studies. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;405:397–406. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00569-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Reyes AS, Rudoy CA. Anatomical substrates for cellular interactions between β1–adrenergic receptor and corticotropin-releasing factor in the amygdala. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Juan W, Narasimman G, Ma M, Inoue M, Saito Y, Wahed MI, Nakazawa M, Hasegawa G, Naito M, Tachikawa H, Tanabe N, Kodama M, Aizawa Y, Yamamoto T, Yamaguchi K, Takahashi T. Betaxolol improves the survival rate and changes natriuretic peptide expression in rats with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003a;41(Suppl 1):S99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Nakagawa T, Yamamoto R, Maeda A, Minami M, Satoh M. Involvement of noradrenergic system within the central nucleus of the amygdala in naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal-induced conditioned place aversion in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003b;170:80–88. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1504-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weddington WW, Brown BS, Haertzen CA, Cone EJ, Dax EM, Herning RI, Michaelson BS. Changes in mood, craving, and sleep during short-term abstinence reported by male cocaine addicts. A controlled, residential study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:861–868. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810210069010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Ciccocioppo R, Parsons LH, Katner S, Liu X, Zorrilla EP, Valdez GR, Ben-Shahar O, Angeletti S, Richter RR. Compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse. Neuroadaptation, stress, and conditioning factors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;937:1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Neurobiology of addiction. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:243–251. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Spangler R, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Increased CRH mRNA levels in the rat amygdala during short-term withdrawal from chronic 'binge' cocaine. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;114:73–79. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]