Abstract

The metal coordinating properties of the prion protein (PrP) have been the subject of intense focus and debate since the first reports of copper interaction with PrP just before the turn of the century. The picture of metal coordination to PrP has been improved and refined over the past decade, and yet the structural details of the various metal coordination modes have not been fully elucidated in some cases. Herein we employ X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy as well as extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy to structurally characterize the dominant 1:1 coordination modes for CuII, CuI and ZnII with an N-terminal fragment of PrP. The PrP fragment constitutes four tandem repeats representative of the mammalian octarepeat domain, designated OR4, which is also the most studied PrP fragment for metal interactions, making our findings applicable to a large body of previous work. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations provide additional structural and thermodynamic data, and candidate structures are used to inform EXAFS data analysis. The optimized geometries from DFT calculations are used to identify potential coordination complexes for multi-histidine coordination of CuII, CuI and ZnII in an aqueous medium, modeled using 4-methylimidazole to represent the histidine side chain. Through a combination of in silico coordination chemistry as well as rigorous EXAFS curve fitting, using full multiple scattering on candidate structures from DFT calculations, we have characterized the predominant coordination modes for the 1:1 complexes of CuII, CuI and ZnII with the OR4 peptide at pH 7.4 at atomic resolution, which are best represented as a square planar [CuII(His)4]2+, digonal [CuI(His)2]+ and tetrahedral [ZnII(His)3(OH2)]2+, respectively.

Keywords: prion, copper, zinc, X-ray absorption spectroscopy, density functional calculations

Introduction

The characterization of metal coordination to the prion protein (PrP) has been an area of special interest to the prion research field since the association of copper with PrP was initially reported in the late 1990s.1,2,3,4 Since this time the range of metals investigated has expanded considerably, however, copper remains a key player in the metallobiochemistry of PrP. The N-terminal region of PrP contains a number of conserved His residues (Table 1) which serve as the primary anchoring residues for interaction with metals. Histidine is a common metal binding ligand in bioinorganic chemistry and is found within binding sites of metallochaperones and reaction sites in enzymes. Within biological systems, histidine-bound copper is used primarily for its ability to take or give up an electron. The His side chain can act as a pH-sensitive switch that responds to changes in pH by altering its protonation state as well as its metal binding capacity.

Table 1.

Multiple sequence alignment for the prion protein N-terminal domain (residues 23-112 shown, human numbering) from representative species.a

| Homo sapiens | KKRPKPGG-WNTGGSRYPGQGSPGGNRYPPQGGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGG |

| Mus musculus | KKRPKPGG-WNTGGSRYPGQGSPGGNRYPPQGG-TWGQPHGGGWGQPHGG |

| Ovis aries | KKRPKPGGGWNTGGSRYPGQGSPGGNRYPPQGGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGG |

| Bos taurus | KKRPKPGGGWNTGGSRYPGQGSPGGNRYPPQGGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGG |

| Homo sapiens | GWGQPHGG--------GWGQPHGGG-WGQGGGTHSQWNKPSKPKTNMKHM |

| Mus musculus | SWGQPHGG--------SWGQPHGGG-WGQGGGTHNQWNKPSKPKTNLKHV |

| Ovis aries | GWGQPHGG--------GWGQPHGGGGWGQGG-SHSQWNKPSKPKTNMKHV |

| Bos taurus | GWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGWGQPHGGGGWGQGG-THGQWNKPSKPKTNMKHV |

| OR4 peptide | Acetyl-KKRPKPHGGGWGQPHGGSWGQPHGGSWGQPHGGGWGQ-NH2 |

Full-length PrP alignments are shown in Supporting Information Table S1.

The prion protein has been linked to an ancient family of metal trafficking/regulating proteins, the ZIP protein family.5 The prion protein appears to play multiple functional roles, some of which are related to trace metal trafficking and homeostasis,6,7,8,9 as well as neuronal differentiation,10 and neuroprotection.11,12 The prion protein also appears to play a critically important role in modulating N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activity through regulation of copper.13

The coordination of copper to the N-terminal domain of mammalian PrP is relatively complex and displays a range of coordination modes which have been characterized in detail.14,15,16 Under low copper occupancy conditions the PrP N-terminal octarepeat domain can coordinate a single Cu2+ ion through multiple His residues, with a Kd in the low nM range.Error: Reference source not found Under high copper occupancy conditions each of the four octarepeat His residues along with several deprotonated amide residues from the immediately adjacent protein backbone serve as the donor ligands, with a Kd in the range of 7-12μM.Error: Reference source not found Intermediate occupancy likely corresponds to a range of coordination modes with differing numbers of coordinating histidines and a range of charge states at each binding site, which has been partially elucidated in recent work by Di Natale, et al.Error: Reference source not found Low and high occupancy coordination for CuII present easily reached end points, whereas characterization of the complex mixture of species under intermediate CuII loadings will likely remain a considerable challenge for coordination chemistry for the foreseeable future. Prior to the current dynamic picture of copper coordination to PrP the plasticity of the PrP N-terminal region for accommodating a complex range of copper coordination structures was problematic for early investigations. Due to these early challenges in characterizing Cu-PrP interactions older research in this area must always be carefully assessed under the lens of current knowledge in order to understand which coordination forms were being characterized in previous work.

The N-terminal region of PrP is a good example of an intrinsically disordered protein, although, in the presence of metals it can attain some structure.17,18,19,20 Because of its disordered nature structural characterization of the PrP N-terminal domain has proven challenging for conventional structure determination methods such as X-ray crystallography and NMR. Due to this significant challenge there is limited experimental data of atomic resolution for this region of PrP. To date there is one crystal structure of copper(II) bound octarepeat fragment, HGGGW,21 which also provides insight into the imposed conformation of the local protein backbone.

The inherent challenges for conventional techniques to characterize the structure of the metal bound forms of PrP opens the door for new methods of characterization, such as structure calculations and molecular dynamics. Computational methods are most effectively employed within the framework of a holistic approach where parameters and structural data from experiment are used to inform model generation and initial conditions. To do this, information regarding the metal coordination geometry, the number and type of ligands, as well as the metal-ligand bond lengths may be required. Such computational approaches are at the forefront of methods to characterize intrinsically disordered proteins and peptides as well as the study of processes leading to protein misfolding where metals are be implicated – noteworthy examples include prion diseases (involving the prion protein), Alzheimer's disease (the Aβ peptide) and Parkinson's disease (β-synuclein).

The N-terminal region of PrP has also been reported to bind other metals.22,23,24,25 Copper coordination to PrP has also been observed to be redox competent, cycling between CuII and CuI.26 Zinc(II), on the other hand, is redox inactive, but has also been implicated in the functional bioinorganic chemistry of PrP.Error: Reference source not found,27,28 Unlike CuII, both CuI and ZnII possess a fully occupied 3d10 outer shell and are therefore colourless and do not present any readily accessible spectroscopic handle with which to probe their coordination properties directly by conventional means. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), however, is an atomic-based technique that exploits the fundamental electronic structure of the element being analyzed and in theory can be used to probe any element of interest.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy, specifically near edge (also called X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy, or XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy, alongside computational chemistry methods, such as density functional theory (DFT) for structure calculations, are highly complementary tools for elucidating chemical and structural information of metal interactions with biological systems – from small molecules, to macromolecular bioinorganic species, to proteins.29 EXAFS is most sensitive to changes in bond length and this can be used as a critical metric for narrowing down the type of coordinating ligand(s) – such as a bound oxo vs. OH− vs. H2O – as well as coordination number and in some cases coordination geometry. Both EXAFS and DFT structure calculations can provide similar atomic-scale resolution information of the local structure around the site of interest. Structural information available from EXAFS of the metal sites within biological systems is typically limited to ~5 Å around the metal centre. This same volume surrounding the central metal atom is sufficient to contain the primary coordinating ligands available from protein side chains and therefore makes a useful scale for generation of structures for DFT calculations. Additionally, EXAFS provides a chemically and structurally sensitive probe which can be used to better inform DFT structure calculations. On the other hand, EXAFS curve fitting with multiple scattering contributions from outer shell atoms requires 3D structural information, which can be obtained from small molecule crystal structures or from DFT-optimized structure calculations. DFT calculations can additionally be used to test alternate structures and chemical forms, as well as provide thermodynamic insight (through calculation of energies (E), enthalpies (H) and entropic components (S)) which can further inform and bolster the choice of models used to fit experimental data.

EXAFS can provide bond lengths accurate to ±0.02 Å, while DFT calculations are typically regarded as accurate to ±0.05 Å, depending on the nature of the chosen functional and basis set, and in some cases the accuracies may be significantly better than this estimate.30 Small molecule crystal structures can also provide insight to supplement EXAFS and DFT, however, crystal packing forces and other factors can mislead,31 and a degree of chemical intuition on the part of the researcher is always required with any of these methods.

Herein we report the first detailed structural characterization of the 1:1 complexes of CuII, CuI and ZnII binding to the octarepeat region of PrP at physiological pH, using a combination of XAS and EXAFS spectroscopy as well as DFT calculations.

Results and Discussion

Structure calculations for CuII, CuI and ZnII

Structure calculations have been performed on multi-histidine model complexes of CuII, CuI and ZnII starting from their aquo complexes. The stepwise dehydration and addition of imidazole donors represents the stepwise binding of metals to the PrP N-terminal domain from a common reference point – their aqueous forms (Figure 1). The use of Mn+(aq) as a starting point is directly relevant to the experimental conditions used herein, however, in vivo these metal ions will likely have different initial coordination, rather than fully solvated, such as bonding to chaperones or other small molecules – in which case the most hydrated complexes modeled in the stepwise coordination schemes shown in Figure 1 will be the least relevant. As the chemical form and coordination environment of copper and zinc are presently unknown within the environment of the synaptic cleft, for example, the choice of a convenient common reference point, which is relevant to our experimental conditions, remains useful. It is anticipated that the most stable complexes from each coordination scheme should be the species observed spectroscopically. The flexibly disordered OR4 peptide, however, may not necessarily adequately accommodate the metal's preferred coordination geometry or number of His ligands, as will be seen in the case of ZnII.

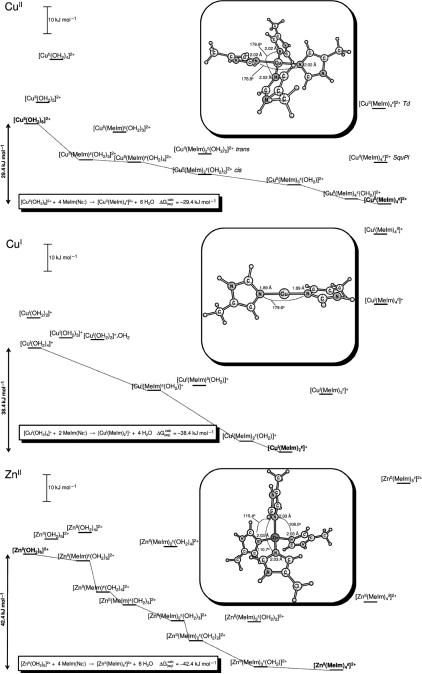

Figure 1.

Calculated aqueous free energy paths for stepwise coordination of (A) CuII, (B) CuI and (C) ZnII by 4-methylimidazole (MeIm) from their corresponding aquo complexes.

The calculated free energies (ΔG(aq)Calc) shown in Figure 1 represent stabilities between calculated models which can also be compared between different metal ions. For example, coordination of the first methylimidazole to CuI gives a calculated ΔG(aq)Calc = −27.0 kJ mol−1, which is larger than the corresponding calculated free energy change for coordination of the first methylimidazole to either CuII or ZnII. The structure calculations are, however, idealized systems which only capture the dominant interactions involved in the coordination of the ligands.

A coordinating imidazole moiety from a His side chain may bind through either the Nδ or Nε ring position,Error: Reference source not found however, all of the complexes we have investigated favour coordination via the Nε-atom, by at least 2 kJ mol−1, or more, per coordinating imidazole, over Nδ coordination. From our calculations we find that coordination of three or more imidazole ligands through the Nε-atom position becomes increasingly unfavourable as each of the methyl substituents on the imidazole rings (which represent the Cβ position of the His side chain) introduce further unfavourable steric interactions. Coordination by 4 Nε atoms was ~25 kJ mol-1 higher in energy than coordination by 4 Nδ-atoms for each of the metals studied. In general, discussion will focus on the Nε-bound species.

Smaller basis sets, such as the 6-31G(d) basis set, used for geometry optimizations, give rise to a D2d distortion bias for 4-coordinate CuII complexes over the expected square planar geometry.32 At the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level the D2d-distorted geometry for [CuII(MeIm)4ε]2+ is calculated to be 5 kJ mol−1 more stable than the square planar geometry but would still be within the calculated ±10 kJ mol−1 accuracy assumed to be inherent in the calculated energies.33 Use of a double-ζ effective core potential basis set, such as LANL2DZ, or a larger Gaussian basis set, such as the 6-311+G(2df,2p) basis set employed herein, recovers the expected square planar coordination geometry fir the Cu2+ centre. The general finding for CuII is that 4-coordinate square planar structures are preferred, with further solvation being best represented through continuum solvation rather than inclusion of additional explicit solvent molecules in the apical positions of the complex. Similar results are found for each of the metals studied. This is a convenient outcome, as additional explicit solvent in relatively weakly coordinating positions at the metal centre may be bound by less than 20 kJ mol−1, and greater stabilization of the waters can usually be achieved through H-bonding to other ligands in the primary coordination sphere of the metal, with a similar binding strength. This consequence means that such waters often drift away from weakly bound coordination sites and adopt other positions during geometry optimizations, and the potential energy surface for exploring the most favourable placements of these waters is relatively flat with many local minima, none of which tend to affect the primary coordination geometry at the metal centre.

Stepwise Coordination of Imidazole to Cu2+

Copper(II) binds to water molecules in a Jahn-Teller distorted tetragonally distorted octahedral geometry, where apical water molecules lie ~0.3 Å further away from the Cu2+ centre than those in the 4 equatorial positions. This distortion of apical solvent positions is observed in some small molecule crystal structures as well (e.g. IGUJAW),34 although recent XAS characterization of dissolved Cu2+ suggests the geometry deviates toward an axially elongated square pyramid.35 Loss of one or more waters from the primary coordination sphere of [CuII(OH2)6]2+ is unfavourable, with formation of [CuII(OH2)5]2(creating a vacant coordination site as a precursor for ligand exchange) requiring 7.6 kJ mol-1, and loss of a second water, forming [CuII(OH2)4]2+, costs an additional 16.6 kJ mol−1 (Figure 1A).

Initial coordination of a single imidazole to [CuII(OH2)6] results in formation of [CuII(MeIm)ε(OH2)6]2+, which is −14.0 kJ mol−1 lower in energy than the aquocopper(II) complex. In terms of relative stability all of the two imidazole complexes calculated with either two or three water molecules are close in energy, and differ by ±10 kJ mol−1, or less. The 4-coordinate [CuII(MeIm)3ε(OH2)]2+, complex can coordinate an additional imidazole, forming the square pyramidal [CuII(MeIm)4ε(OH2)]2+complex, which further stabilizes the system by –5.7 kJ mol−1. Loss of the final explicit water molecule from the apical position above the plane of imidazole donors generates the square planar [CuII(MeIm)4ε]2+ complex, which is the end point of the calculated series and stabilizes the system by a final −1.7 kJ mol−1.

The four imidazole complex (which does not contain any explicitly-bound waters) is the most stable coordination mode calculated for CuII, implying that within the employed computational framework the coordination of explicit water molecules to the apical positions is less stabilizing than liberating these molecules and allowing them to be ‘solvated’ in the bulk solution, where each water is solvated by –16.4 kJ mol−1 according to our methods (vide infra). In fact, allowing any additional explicit solvent molecules to form H-bonds (instead of occupy the apical coordination sites) is more favourable, indicating that the secondary solvation shell may be more strongly bound than the apical positions of the copper site and that solvent in these positions is best represented by the dielectric continuum.

The most favourable geometry for the 4 imidazole complex has the imidazole rings in a paddle wheel arrangement, where each ring is rotated to an intermediate position half way out of the primary coordination plane and also away from perpendicular. Distorting the [CuII(MeIm)4ε]2+ complex away from a square planar geometry into a tetrahedral geometry comes at an energetic penalty of +35.0 kJ mol−1, while imposing an ideal square planar geometry on the [CuII(MeIm)4ε]2+ complex is also disfavoured with the employed computational method, requiring +15.0 kJ mol−1 to do so.

The structures for the initial hydrated complexes are in agreement with similar ab initio calculations carried out previously.36,37 A search of the Cambridge Structural Database38,39 confirms the preference of CuII for square planar coordination by 4 imidazole-type complexes and provides a reasonable comparison for the DFT-calculated [CuII(MeIm)4ε]2+ structure. The small molecule crystal structure IGUJAW reveals a square planar arrangement of four 4-methylimidazole ligands within a Jahn-Teller distorted geometry, with the axial positions occupied by water molecules appearing to be dipole bound (as opposed to coordinating with the O-atom lone pair directed toward the metal centre).Error: Reference source not found The average Cu–Nε bond length from IGUJAW is 2.00 ±0.02 Å (the DFT-calculated bond lengths for [CuII(MeIm)4ε]2+ are 2.023 ±0.001 Å), while the axially bound waters in the crystal structure lie at ~2.6 Å, more consistent with being dipole-bound.. Using the B3LYP/6-31G(d) method for geometry optimizations Pushie et al. have demonstrated a preference for D2d-distorted geometries away from square planarity for CuII,Error: Reference source not found which is similar to the structural distortions reported in other computational studies of CuII coordination with multiple His donors.40,41

For the start and end point of the series in Figure 1A the ΔG(aq)calc for formation of [CuII(MeIm)4ε]2+ from hexaaquocopper(II) is −29.4 kJ mol−1.

Stepwise Coordination of Imidazole to Cu+

The range of accessible coordination modes and complexes involving Cu+ are greatly simplified compared to Cu2+, due in part to the lower total charge and preference for reduced coordination number. Cu+ generally prefers to form digonal 2-coordinate complexes overall (Figure 1B), and like the Cu2+ examples there is a clear preference for coordination via the Nε-atom of the imidazole ring over binding through the Nδ position.

In aqueous solution the most stable Cu+ species calculated contains four water molecules within the primary coordination sphere of the metal, however, the coordination geometry appears to be closer to a distorted T-shaped complex with the fourth water occupying an apical position, and is only stabilized by 3.5 kJ mol−1 over [CuI(OH2)3]+. No additional complexes with explicitly coordinating waters were found; in fact, addition of one or more waters to the secondary solvation shell of [CuI(OH2)2]+ (i.e. H-bonded to the coordinating water molecules) was found to be highly favourable compared to coordination at the metal centre and may indicate that the 2-coordinate model for Cu+(aq) is a more reasonable representation of this species in solution, with additional strongly bound waters occupying the secondary solvation shell.

Loss of water from the primary coordination sphere to form [CuI(MeIm)2ε]+ stabilizes the system by –38.4 kJ mol−1. Aside from the addition of water, addition of a further imidazole ligand to [CuI(MeIm)2ε]+ incurs an energetic penalty of 22 kJ mol−1.

Our observation that the initial form of aquocopper(I) is perhaps better described as a two-coordinate complex is supported from previously published work.Error: Reference source not found,Error: Reference source not found For example, Dalleska, et al. have employed collision-induced dissociation of solvated Cu+ and analyzed the product species by mass spectrometry.42 Their results indicate that the first two water molecules are strongly bound (as evidenced by their bond enthalpies at 298 K), whereas addition of a third and fourth water molecule reduces the apparent bond enthalpy by roughly an order of magnitude. Dalleska, et al.'s mass spectrometry resultsError: Reference source not found are effectively in the gas-phase, and therefore we have compared our ΔG(g)calc bond dissociation energies (BDE) with their data, corrected to 298 K. Dalleska, et al. report that the third water in Cu+(H2O)3 is bound by –16.3 kJ mol−1 (relative to Cu+(H2O)2),Error: Reference source not found while our calculated BDE for coordination of a third water molecule yields –7.8 kJ mol−1. Removing the third water from the primary coordination sphere and allowing it to H-bond to the digonal 2-coordinate Cu+ species gives −8.2 kJ mol-1. These gas-phase comparisons also highlight the effect of solvation on such weakly-bound structures. Furthermore, Mykhalichko, et al. have reported a small molecule crystal structure which contained a co-crystallized digonal [CuI(OH2)2]+ species, (structure CIKRUJ).43

There are numerous examples of digonal Cu+ complexes bound by imidazole-type ligands in the Cambridge Structure Database. For example, the bis(2-methylbenzimidazole)-copper(I) complex (ETERIE) is a linear complex with Cu–N bond lengths of 1.874 Å.44 The EHEPOX small molecule crystal structure contains numerous bis(imidazole)-copper(I) complexes which co-crystalized, and display a range of Cu–N bond lengths averaging 1.86 ±0.03 Å.45 Our DFT-optimized structure has the NεCu–Nε angle very nearly linear (179.6°), in good agreement with the various crystal structure examples, and our calculated Cu–Nε bond length is 1.89 Å. The crystal structures of these complexes reveals that the donor rings are almost always co-planar, whereas our [CuI(MeIm)2ε]+ structure has each imidazole ring rotated ~90° relative to one another. The barrier to rotation of one imidazole ring is less than 5 kJ mol-1 (data not shown) and it is likely that the observed co-planarity in the crystal structures is due to crystal packing forces. Shearer and Szalai46 have identified the analogous CuI coordination mode for the Aβ peptide, which is associated with Alzheimer's disease, and a similar digonal complex has been used by Furlan, et al.47 in molecular simulations of CuI bound to Aβ.

For the start and end point of the series shown in Figure 1B the ΔG(aq)calc for formation of [CuI(MeIm)2ε]+ from an aquocopper(I) species is –38.4 kJ mol−1.

Stepwise Coordination of Imidazole to Zn2+

To compliment the study of Cu2+ and Cu+ we also carried out the same series of in silico reactions for Zn2+, which has the same total charge as Cu2+, and the same d-orbital configuration as Cu+ (d10). Again, like Cu2+, the expected trend toward higher coordination numbers due to the greater total charge on the metal ion is observed, although it also appears that the imidazole coordination steps and dehydration steps each result in slightly greater stabilization overall (Figure 1C) than was observed in the Cu2+ series. This larger magnitude of stabilization for each of the Zn2+ complexes also tended to manifest itself in the number of stable zinc structures that were identified. Unlike the Cu2+ series, which appears to have a somewhat more plastic coordination environment and can accommodate a wider range of coordination modes with loosely-bound ligands (Figure 1A), Zn2+ tended to have a more clearly defined preference for specific coordination modes and additional waters were readily lost from the primary coordination sphere during geometry optimizations (Figure 1C), which prompted the geometry optimizations to be restarted without these excess waters.

From the hexaaquozinc(II) complex, [ZnII(OH )2]2+, the initial coordination of a single imidazole ligand results in a net stabilization, with the formation of [ZnII(MeIm)ε(OH2)52+] lying –1.7 kJ mol−1 below the fully solvated species. Loss of an additional water molecule from this complex stabilizes the complex by –2.3 kJ mol−1, generating [ZnII(MeIm)ε(OH2)4]2+.

Binding the third imidazole to to the Zn2+ centre may be a concerted process with the loss of water, as the formation of [ZnII(MeIm)3ε(OH2)2]2+ from [ZnII(MeIm)2ε(OH2)2]2+ costs 7.1 kJ mol−1, while subsequent loss of a water molecule from this complex to generate the tetrahedral [ZnII(MeIm)3ε(OH2)]2+ complex then stabilizes the system by 16.6 kJ mol−1. From this complex, loss of the final water molecule and coordination of a fourth imidazole donor affords a negligible stabilization of 0.6 kJ mol−1 and may also be a concerted process with loss of water, as the water molecule is readily expelled from the primary coordination sphere during geometry optimization once the additional MeIm ligand is introduced. Addition of further imidazole donors is highly unfavourable, as evidenced by formation of [ZnII(MeIm)5ε]2+, which costs +69.1 kJ mol−1.

The ability for Zn2+ to form 4-coordinate tetrahedral complexed with similar donor atoms is supported by a search of the Cambridge Structure Database. For example, Kojima, et al. have reported a structurally analogous ZnII(imidazole)4ε-like complex (CATZUS10), which displays the same preference for a tetrahedral geometry with Zn–N bond lengths averaging 2.00 ±0.03 Å,48 compared to our average calculated Zn–Nε bond length of 2.011 ±0.003 Å.

In regards to the solvated structure of aquozinc(II), there are countless examples of 6-coordinate [ZnII(OH2)6]2+ in the Cambridge Structure Database, providing ample support for our assertion that this is a reasonable representation of Zn in aqueous solution. There are few examples of pentaaquozinc(II) species in the CSD, with the entries DEHFUR49 and YUPKAW50 representing credible bona fide [ZnII(OH2)5] species. Many other apparent pentaaquozinc(II) species that arise through structure and formula searches appear to in fact be the result of disorder within the crystal, as evidenced by the presence of additional atoms within the Zn coordination sphere and apparently distorted coordination geometries (e.g. ASACON51 and FURWUL52). One apparent example of a 4-coordinate tetraaquozinc(II) species, ZMAZON, appears to be a spurious entry in the database as the structure was not refined and the original terse report asserts that the zinc atoms are 6-coordinate (although the structure is not clear from the original paper).53

For the start and end point of the series shown in Figure 1C the ΔG(aq)calc for formation of [ZnII(MeIm)4ε]2+ from hexaaquozinc(II) is –42.4 kJ mol−1.

In Situ Photoreduction of CuII

For dilute aqueous metalloprotein samples the high flux density on modern beamlines and the relatively large photoabsorption cross section at lower X-ray energies (e.g. energies corresponding to the first row transition metals) means that a large amount of energy from the incident beam is absorbed by solvent. This gives rise to a range of molecular fragments and radical species which can potentially promote photooxidation or photoreduction of the solute being analyzed.54 Photoreduction of CuII samples appears to be primarily dependent on the flux density of the incident beam, but there also appears to be additional contributing factors, possibly including the coordination environment of the CuII sites within the sample and their individual reduction potentials. For samples that are slow to photoreduce, and depending on the signal-to-noise present in the data, the effect of photoreduction on the EXAFS spectrum may not be apparent from scan-to-scan during averaging of EXAFS spectra. Figure 2 demonstrates the effects of in situ photoreduction of CuIIOR4 by comparing the first EXAFS spectrum with the sixth spectrum, representing the end point of a typical averaging scan. For clarity the backscattering contributions beyond 2.3 Å in the EXAFS Fourier transform have been backtransformed and subtracted from the parent EXAFS spectrum for both the CuII and photoreduced data sets. These filtered EXAFS spectra more clearly show the change in primary coordination upon photoreduction. The primary backscattering interactions in the EXAFS Fourier transforms (Figure 2) are best modeled by 4 equivalent donor atoms in the case of CuII, and 3 donor atoms in the photoreduced case. Photoreduction of CuIIOR appears to result in loss of one of the four His donors from the CuII complex. As the EXAFS data is collected at 10 K there is very little structural motion possible within the frozen ensemble of solute molecules, and therefore only minimal reorganization is possible. We propose that photoreduction of CuII results in formation of a pseudo T-shaped complex with dissociation of one His ligand and concomitant shortening of two mutually trans donor groups across the metal centre, with the remaining donor atom at a slightly longer distance from the metal centre. The 3-coordinate photoreduced species is an intermediate complex, representing an artifact of the frozen matrix, which restricts the coordination environment from fully relaxing to the preferred coordination mode of a digonal complex bound by two His residues. According to the in silico coordination complexes for CuI this would correspond to a coordination geometry that is at least 22 kJ mol−1 higher in energy than the preferred digonal 2-coordinate geometry.

Figure 2.

The effect of in situ photoreduction of a dilute aqueous CuIIOR4 complex. The scattering interactions beyond 2.3 Å have been filtered in order to isolate the change in the primary backscattering interaction as a result of copper photoreduction.

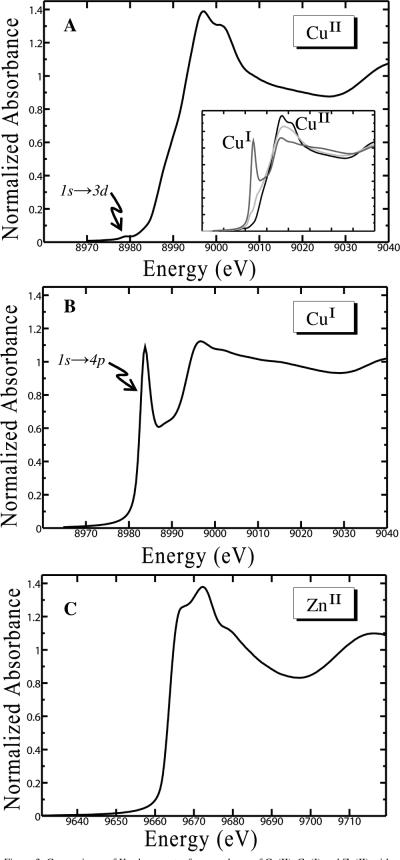

The inset plot in Figure 3A clearly demonstrates the effect of in situ photoreduction in the copper K-edge near edge spectrum. Shown for comparison in the inset plot is the nonphotoreduced CuII spectrum (see Material & Methods), which shows the clearly defined, and formally dipole forbidden, 1s→3d transition, characteristic of the CuII oxidation state. Also shown for comparison in the inset plot is the Cu K-edge near edge spectrum of a digonal 2-coordinate His complex of fully reduced CuI (corresponding to CuIOR4 from Figure 3B). In agreement with the apparent reduction in coordination number for the photoreduced species the near edge spectrum of the photoreduced species is remarkably similar to the spectrum of a bona fide 3-coordinate CuI species, based on the apparent contributions to the rising edge (Figure 3b, I-11 in reference 55), which corresponds to the [CuI2(mxyN6)]2+ complex.56

Figure 3.

Comparisons of K-edge spectra for complexes of CuII, CuI and ZnII with the OR4 peptide. (A) CuII near edge spectrum, inset plots show the parent CuII near edge (black) with the in situ photoreduced species (light grey) and the CuIOR4 near edge (dark grey); (B) CuI near edge; (C) ZnII near edge.

The observed photoreduction occurred under standard sample preparation and operating conditions for EXAFS data collection (see Material and Methods section). Without procedures to protect against in situ photoreduction this will continue to be a problem at 3rd generation and later synchrotron sources, as higher flux densities are delivered to end stations.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopic Characterization of Copper and Zinc binding to OR4

The K-edge near edge portion of the X-ray absorption spectrum exhibits transitions from the core 1s orbital and is sensitive to the oxidation state of the metal as well as the outer shell orbitals and coordination. The CuII K-edge near edge spectrum (Figure 3A) shows the characteristic 1s→3d transition at 8979.1 eV, indicative of 3d9 CuII. The CuI K-edge near edge spectrum (Figure 3B) demonstrates a sharp and intense 1s→4p dipole-allowed transition at 8983.8 eV, which is characteristic of 3d10 CuI in a linear 2-coordinate geometry. The intensity of the transition indicates a highly centrosymmetric environment about the CuI centre, which is the result of the 2-coordinate digonal geometry about the metal centre, as was found for the in silico coordination study of CuI in Figure 1B (vide supra). The photoreduced copper species inset in Figure 3A does not demonstrate this intense peak, instead there are a number of shoulders on the rising edge which are more consistent with the reduced symmetry of a 3-coordinate CuI, as discussed above. The ZnII K-edge near edge spectrum (Figure 3C) does not display any pre-edge feature, as would otherwise be expected for a 3d10 metal in a tetrahedral geometry.

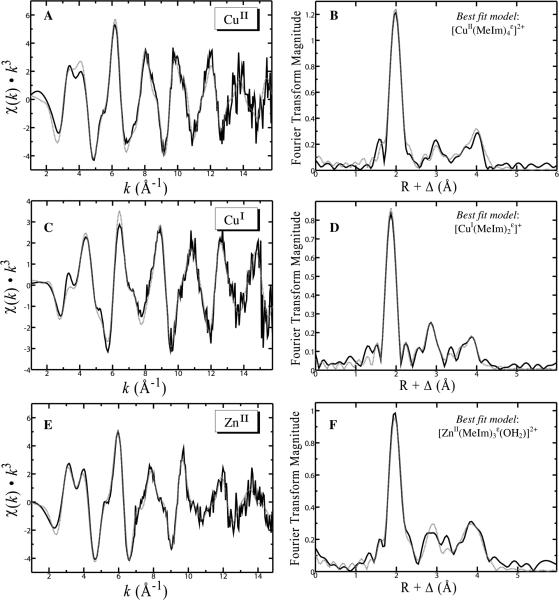

Each of the EXAFS spectra (Figure 4) demonstrate the multiple beat pattern characteristic of multiple scattering interactions arising from the coordinated imidazole rings of the His side chains. These EXAFS oscillations are of lower amplitude than those of the primary backscattering atoms and have a higher frequency of oscillation, giving rise to additional structure on top of the larger amplitude oscillations from the primary backscattering atoms. This is most apparent at the low k-range, where the first 2-3 oscillations in the EXAFS spectrum clearly show additional structure, such as splitting and pronounced shoulders (Figure 4A, C and E). These features can often serve as an initial indicator of His coordination before inspection of the EXAFS Fourier transform or performing EXAFS curve fitting. Fitting of the EXAFS and EXAFS Fourier transforms for each of the 1:1 complexes only required imidazole donor atoms (and a coordinating water in the case of Zn2+). Inclusion of any number of amide moieties coordinating via a deprotonated backbone N-atom deteriorated fits to the experimental data. Furthermore, the XAS near edge spectra were remarkably similar to the corresponding near edge spectra in the presence of excess imidazole (data not shown).

Figure 4.

EXAFS oscillations and EXAFS Fourier transforms for CuII (A, B), CuI (C, D) and ZnII (E, F) bound to the OR4 peptide fragment of mouse PrP. EXAFS Fourier transforms are phase corrected for metal–N backscattering. Solid lines show experimental data, broken lines are the best fit from bold parameters in Table 2.

EXAFS Curve Fitting for CuIIOR4

Once the complicating photoreduction was mitigated it was possible to obtain significantly improved fits to the EXAFS spectrum for CuII with the OR4 peptide. Initial curve fitting using single scattering paths for 4 Cu–N/O at 1.98 Å gave the best fit to the primary backscattering atoms (Table 2). Inclusion of one or more additional longer range light atoms marginally improved the fit, although these longer range interactions have a relatively high δ2, as might be expected for weakly coordinating solvent in the apical position of a Jahn-Teller distorted octahedral CuII complex, much of the apparent improvement is due to mutual cancellation between backscatterers and their inclusion is otherwise difficult to justify without supporting data.

Table 2.

Summary of initial partially refined EXAFS curve fitting results.a

| Primary Metal–N Coordination | Additional Metal–C/N/O Interactions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | R | σ 2 | N | R | σ 2 | ΔE0 | error F | |

| CuIIOR4 | ||||||||

| Single Scattering Path Models | ||||||||

| 4 | 1.981(3) | 0.0036(2) | −11.2(7) | 0.4622 | ||||

| 4 | 1.983(3) | 0.0036(2) | 1 | 2.30(3) | 0.0128(4) | −10.9(8) | 0.4456 | |

| 4 | 1.984(3) | 0.0036(2) | 2 | 2.32(2) | 0.023(5) | −10.4(8) | 0.4435 | |

| 4 | 1.984(3) | 0.0036(2) | 1 | 2.25(2) | 0.009(3) | −10.5(9) | 0.4402 | |

| 1 | 2.46(2) | 0.009(3) | ||||||

| [CuII(MeIm)4ε]2+, Square Planar, with full multiple scattering | ||||||||

| 4 | 1.984(2) | 0.0037(1) | +0.2(4) | 0.3281 | ||||

| +20 Unlisted single and multiple scattering paths b | ||||||||

| CuIOR4 | ||||||||

| Single Scattering Path Models | ||||||||

| 2 | 1.873(3) | 0.0022(2) | −10.5(9) | 0.5212 | ||||

| 3 | 1.870(4) | 0.0046(3) | −11.7(9) | 0.6586 | ||||

| 2 | 1.873(3) | 0.0022(2) | 1 | 2.27(3) | 0.018(6) | −10(1) | 0.4964 | |

| [CuI(MeIm)2ε]+, Digonal, with full multiple scattering | ||||||||

| 2 | 1.875(2) | 0.0021(1) | − 1.6(5) | 0.3333 | ||||

| +12 Unlisted single and multiple scattering paths b | ||||||||

| ZnIIOR4 | ||||||||

| Single Scattering Path Models | ||||||||

| 4 | 1.993(5) | 0.0054(3) | −14(1) | 0.5790 | ||||

| 6 | 1.993(7) | 0.0092(5) | −14(1) | 0.6470 | ||||

| 4 | 1.990(6) | 0.0054(3) | 2 | 2.47(2) | 0.013(3) | −16(1) | 0.5632 | |

| 3 | 1.987(6) | 0.0032(5) | 1 | 2.11(2) | 0.004(2) | −12(1) | 0.5712 | |

| [ZnII(MeIm)3ε(OH2)]2+, Tetrahedral, with full multiple scattering | ||||||||

| 3 | 1.990(3) | 0.0034(2) | 1 | 2.09(1) | 0.0056(2) | − 1.9(6) | 0.3432 | |

| +43 Unlisted single and multiple scattering paths b | ||||||||

Coordination numbers, N, interatomic distances R (Å), Debye-Waller factors σ2 (Å2), and threshold energy shift ΔE0 (eV). The fit error parameter F is defined as , with the summation being over data points included in the fit. Values shown in bold represent the best fit obtained. Values in parentheses are the estimated standard deviations obtained from the diagonal elements of the covariance matrix; these are precisions and are distinct from the accuracies which are expected to be larger (ca ±0.02 Å for R, and ±20% for N and σ2), and that relative accuracies (such as comparing two different Cu—O/N bond-lengths) will be more similar to the precisions. The k-range of the CuII and CuI data was fitted from 1.0 to 15.75 Å−1 and from 1.0 to 14.0 for ZnII.

A full summary of all scattering paths from the best EXAFS fits are listed in Supporting Information Table S2.

Performing full multiple scattering calculations on the DFT optimized square planar [CuII(MeIm)4ε]2+ complex produced a total of 24 scattering paths (Table S2). Four of these scattering paths were due to the Cu–Nε atoms, which differed in scattering path length of less than 0.01 Å, and were combined into a single scattering path (shown in Table 2) for EXAFS curve fitting. The refined fit of the square planar [CuII(MeIm)4ε]2+ complex (Figure 4 A and B) gave the best fit overall to the experimental data. Attempts to include additional longer range Cu–O backscattering contributions from 2.3 – 2.5 Å to the refined fit markedly deteriorated the fit, indicating that any weakly coordinating solvent in these positions do not significantly contribute to the EXAFS spectrum in Figure 4 A. The results of the EXAFS curve fitting indicate that the predominant coordination mode for CuII with the OR4 peptide at physiological pH is a 4-coordinate square planar [CuII(His)4]2+ complex. A summary of the EXAFS curve fitting results for alternate potential coordination modes for CuII are summarized in Fig S1 in supplementary material.

EXAFS Curve Fitting for CuIOR4

The chemically reduced copper complex with the OR4 peptide presents a relatively simple digonal coordination environment as the dominant species, evidenced from the initial single scattering fits to the data (Table 2). As was observed in the CuII case, inclusion of an additional longer range backscattering interaction (such as a water molecule – as shown in the summary of alternate potential coordination modes for CuI in Fig S2 in supplementary material – appears to improve the fit error, however, the δ2 for such paths are very large and cancels with some of the amplitude from the closer shell of backscattering atoms. Taking all fit parameters into account the best initial fit is best modeled by two Cu–N/O backscattering atoms at 1.87 Å.

Using the DFT calculated structure for the [CuI(MeIm)2ε]+ complex as input for the multiple scattering calculation produced a total of 14 scattering paths (Table S2). Two of these scattering paths corresponded to Cu–Nε distances which differed by only 0.0001 Å and were combined into a single scattering path (shown in Table 2). Refinement of the scattering interactions (Figure 4 C and D) gave the best fits overall to the experimental CuI data. The predominant CuI complex with the OR4 peptide at physiological pH is best represented as a digonal 2-coordinate [CuI(His)2]+, with no additional coordinating ligands apparent.

EXAFS Curve Fitting for ZnIIOR4

The zinc complex with the OR4 peptide, as discussed above, represents a 4-coordinate complex. Initial fits using single scattering paths (Table 2) confirmed that 4-coordinate models were optimum, while a lower fit error required inclusion of additional long-range backscattering interactions which were not chemically meaningful. Overall the best initial fits correspond to either 4 equivalent Zn–N/O backscattering atoms at 1.99 Å or 3 light backscattering atoms at 1.99 Å and one additional light atom at 2.11 Å (Table 2). A summary EXAFS curve fitting results for potential coordination modes for ZnII are shown in Fig S3 in supplementary material.

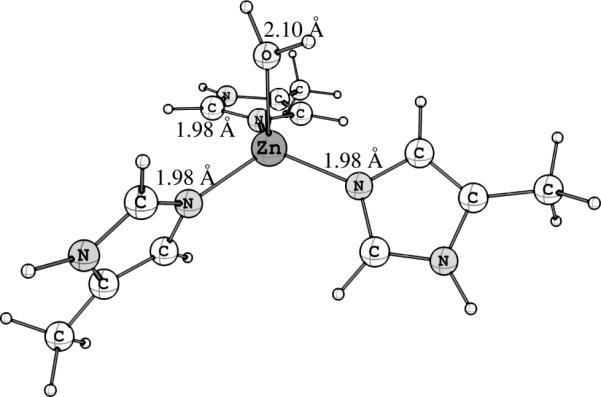

Using the tetrahedral [ZnII(MeIm)3ε(OH2)]2+ complex from DFT calculations as input for the multiple scattering calculation produced a total of 47 scattering paths and produced the best fit to the data (Table S2). The optimized bond lengths in this complex gave an average Zn–Nε distance of 1.979 ±0.003 Å and a Zn–Owater distance of 2.097 Å. The theoretical EXAFS resolution, approximated as π/2Δk (where Δk is the extent of the data in Å−1), is 0.01 Å and places the Zn–O backscattering interaction close theoretical resolution limit of data. Three of the calculated scattering paths corresponded to Zn–Nε distances which differed by less than 0.003 Å and were combined into a single scattering path (roughly 1.99 Å), with the slightly longer Zn–Owater distance kept as a separate backscattering path. The best fit refinement to the EXAFS data (Figure 4 E and F) gave 3 Zn–Nε backscattering paths at 1.99 Å and Zn–Owater at 2.09 Å in a tetrahedral geometry, in good agreement with the related DFT-calculated structure.

Further analysis of the ZnII K-edge near-edge spectrum (Figure 3C) revealed that the near edge could be fit by a linear combination of 3 major components, based on model spectra for ZnSO4 in aqueous solution (i.e. Zn2+(aq)), ZnII in the presence of an excess of imidazole (the EXAFS of which is best fit as [ZnII(His)4]2+) and the near edge spectrum of carbonic anhydrase, a bona fide 3 His, 1 water ZnII coordination environment. These three components are best fit to the ZnIIOR near edge spectrum in a 0.11 Zn(aq), 0.38 [ZnII(His)4]2+ and 0.51 [ZnII(His)3(OH2)]2+ ratio. The sum of these fractional occupancies gives a total of 3.18 Zn–Nimidazole donors and 1.04 Zn–Owater donors as the apparent coordination in solution, very close to the best fit modeled.

Attempts to fit the [ZnII(MeIm)4ε]2+ model to the data deteriorated the fit. The Zn–Nε bond lengths in the 4 MeIm model from the DFT optimizations are 2.011 ±0.003 Å, and attempts to fit this model to the EXAFS data resulted in Zn–Nε bond lengths converging closer to the bond lengths corresponding to [ZnII(MeIm)3ε(OH2)]2+. Additionally, the DFT optimized hydroxyl-bound [ZnII(MeIm)3ε(OH)]+ complex (not shown) gives a significantly different picture for the bond lengths within the coordination environment, with 3 Zn–Nε at 2.04 ±0.01 Å and Zn–O(H) at 1.85 Å. There is no evidence in the EXAFS spectrum of ZnIIOR4 for any significant contribution from such a short backscattering interaction, leading this model to be ruled out. Similarly, representing the single O-atom donor with N-methylacetamide, as a model of the peptide backbone, resulted in 3 Zn–N bond lengths of 2.00 Å and a Zn–O bond length of 1.99 Å in the DFT-optimized complex, but using these bond lengths also deteriorated the fit to the EXAFS spectrum (data not shown).

The DFT calculations in Figure 1C indicate that the [ZnII(MeIm)3ε(OH2)]2+ complex lies very close in energy to [ZnII(MeIm)4ε]2+. The EXAFS data (Table 2 and Figure 4 E and F) indicate that coordination by 4 His residues is not the dominant complex formed by ZnIIOR4 in aqueous solution at physiological pH. The mixed coordination forms for Zn2+ is somewhat at odds with the DFT and EXAFS results for both CuIIOR4 and CuIOR4, which are both predicted to coordinate His residues up to their optimal coordination number, while the mixture of ZnII species is best represented as [ZnII(His)3(OH2)]2+ as the apparently predominant coordination mode at physiological pH. As ZnIIOR4 does not fully saturate with 4 His coordination, despite having the larger total ΔG(aq)Calc for binding 4 MeIm ligands compared to CuII or CuI (Figure 1), this may indicate a conformational preference on the part of the PrP sequence, which may have a higher thermodynamic penalty for structuring itself in a manner that can orient all 4 His ligands in an orientation where they are presented in the tetrahedral arrangement preferred for Zn2+ coordination (as opposed to a digonal, square planar, or pseudo square planar environment for copper). The apparent plasticity of the CuII coordination environment may also play a role, as it appears to be able to accommodate coordination geometries with D2d distortions away from a purely square planar geometry. In the case of CuI, on the other hand, the lower coordination number means any two of the OR4 His residues could serve as donor ligands, thereby further relaxing the OR4 conformational requirements for metal ligation.

Conclusion

Density functional structure calculations have been employed to thoroughly characterize the stepwise coordination of His residues (modeled using the MeIm ligand) to the aqueous metals Cu2+, Cu+ and Zn2+ metal ions. The results of the calculated aqueous free energy change for these reactions indicates that coordination by multiple histidines and dehydrating the primary coordination sphere is preferable in all cases. The DFT calculations also yield structures for each coordination mode which can be used as a starting point in multiple scattering calculations for EXAFS curve fitting.

Using a combination of DFT structure calculations and EXAFS spectroscopy we have identified the predominant coordination modes for copper and zinc in aqueous solution at pH 7.4 with the OR4 peptide as [CuII(His)4]2+ in a square planar environment, [CuI(His)2]+ in a digonal coordination environment, and tetrahedral [ZnII(His)3(OH22+)].

Chattopadhyay, et al. have reported previously that Cu2+ appears to be bound by four His residues, deduced through inference from the close similarity between the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrum of Cu2+ (collected under similar conditions, such as pH, etc.) and Cu2+ in the presence of excess imidazole.Error: Reference source not found Unlike Cu2+, however, the coordination findings reported herein for Cu+ and Zn2+ with the octarepeat region of PrP are new and have not been reported previously. Moreover, based on our DFT structure calculations and EXAFS data we have clarified the structure of each metal site with sufficient resolution to bolster further atomistic computational models.

We find no evidence for involvement of Gly residues in the coordination of Cu2+, Cu+ or Zn2+, based on similarities between the XAS near edge spectra of these same metals with multiple imidazole donors, as well as deteriorated EXAFS curve fits upon inclusion of any number of amide moieties. Furthermore, multi-imidazole complexes containing a metal-O-atom distance for coordination by a protonated amide model were ~0.1 Å shorter than the corresponding metal-O(water) bond lengths and the average metal-ligand bond lengths were shorter than could be reconciled with our EXAFS data.

Photoreduction of Cu2+ samples was identified as an issue early-on in the study and changing to faster EXAFS spectrum acquisition times as well as averaging scans from fresh unexposed sample for each sweep of the spectrum markedly improved the quality of the Cu K-edge near edge spectrum as well as the EXAFS.57 Without these precautions a significant amount of photoreduced copper is generated in situ during EXAFS data acquisition and the resulting spectrum will correspond to a mixture of Cu2+ and photoreduced copper species. Herein we have shown that the effect of photoreduction tends to alter the parent Cu2+ coordination in favour of a more Cu+-like structure, with altered coordination number, geometry and bond lengths. Because the in situ photoreduction occurs at low temperature (i.e. 10 K) there is very little molecular rearrangement possible and therefore the photoreduced copper structure is best represented as an intermediate form between the preferred structures for Cu2+ and Cu+.

A striking finding from the EXAFS curve fitting analysis is that despite Zn2+ having the largest calculated free energy of binding Zn2+ does not saturate with a full complement of His ligands, unlike Cu2+ and Cu+, which where were both in keeping with the in silico coordination study. The EXAFS curve fitting clearly indicates that the best fit is obtained with [ZnII(MeIm)3ε(OH2)]2+ and this represents both the dominant coordination mode as well as the weighted average of the predominant coordination modes for the zinc species present under the experimental conditions. The discrepancy between the observed structure and the calculated stability may indicate a conformational preference on the part of the OR4 peptide, which may have a higher thermodynamic penalty for structuring itself in a manner that can orient all four His donors in a tetrahedral arrangement to fully accommodate Zn2+, as opposed to orienting itself in a conformation that presents the His residues a square planar arrangement (or pseudo square planar environment).58 It must be reiterated, however, that the calculated free energy difference between the [ZnII(MeIm)3(OH2)]2+ and [ZnII(MeIm)4]2+ is negligible and may partly explain the presence of mixtures of Zn2+ species. Also, conformational preferences are not represented in the simplified DFT models of the potential coordination structures shown in Figure 1. The apparent plasticity of the CuII coordination environment may also play a role, as Cu2+ appears to be able to accommodate slight deviations in its preferred coordination geometry, with significant D2d distortions only costing a few kJ mol–1. The lower coordination number for Cu+, on the other hand would be expected to have the lowest imposed conformational requirement on the OR4 peptide.

The calculated binding free energies for Cu2+ and Zn2+ appear to be contrary to the Irving-William's series, which would predict Cu2+ to have greater stabilization through multi-His bonding than Zn2+. The thermodynamic calculations were repeated at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level as well as using the LANL2DZ basis set for the metal centres and show the same preference for Zn2+ to be more greatly stabilized in multi-imidazole complexes than Cu2+. Given the strong preference for coordination by multiple imidazole-type donors (and only weak association with additional waters in the case of Cu2+) a significant source of stabilization of these complexes may arise from relaxation of unfavourable steric interactions between the imidazole donors, which will be least favourable in a 4-coordinate square planar geometry and maximally favoured in a tetrahedral geometry (with the latter also being relatively disfavoured by Cu2+).

As the PrP N-terminal domain remains highly flexible in solution, even following metal coordination, its structural characterization has been a challenge for conventional experimental methods. Computational methods, on the other hand, such as molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo methods, may be able to address some of these challenges.Error: Reference source not found, As multiple His side chains are required for the 1:1 metal complexes this will significantly reduce the number of potential conformations for this region of PrP. Such computational methods, however, require the type of detailed structural information afforded through the EXAFS results herein to define the metal coordination environment for simulation.

Copper binding to the N-terminal domain of PrP has been shown to be redox active.Error: Reference source not found The structural characterizations of the most stable CuII and CuI oxidation states herein provide vital atomic resolution information for rationalizing the observed chemistry of this system. Other researchers have previously characterized copper binding to the Aβ peptide, associated with Alzheimer's disease.Error: Reference source not found,Error: Reference source not found Shearer and Szalai have identified the same type of CuI coordination environment as reported in this work,Error: Reference source not found however, in the case of their CuII data there appears to be significant photoreduction, with no apparent 1s→3d pre-edge peak in the near edge spectrum, and this may have implications for their proposed CuII structure.

The different metal coordination geometries revealed by EXAFS spectroscopy indicate how PrP uniquely responds to Cu+, Cu2+ and Zn2+ and these structural features are of fundamental interest in understanding the uptake of metal-PrP complexes in vivo.

Experimental Section

Sample Preparation

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The N-terminal and acetylated and C-terminally amidated peptide Ac-PHGGGWGQ(PHGGSWGQ)2PHGGGWGQNH2 (designated OR4) was generated based on the N-terminal sequence of mouse PrP (Table 1), and prepared by solid-phase synthesis using standard fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) methods, purified using reverse phase HPLC and characterized by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS).

Samples for XAS were prepared in aqueous solution with 5 mM peptide in degassed buffer containing 20mM MOPS buffer and 30% glycerol (v/v) as a glassing agent. Metal stock solutions for CuII and ZnII were prepared from their sulfate salt, titrated to a final concentration of 4.9 mM Metal2+ (~0.98 metal : 1 peptide). Solutions were adjusted to pH 7.4 using concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) and potassium hydroxide (KOH) solutions. Solutions were loaded into 2×3×25 mm acrylic cuvettes and flash frozen in a slurry of liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane. The CuI sample was prepared from the CuII-peptide complex by adding 20 mM sodium ascorbate in degassed buffer as a mild reducing agent. The solution was left to equilibrate for 30 minutes and was then loaded into a cuvette and frozen as above.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

XAS measurements were conducted at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) with the SPEAR storage ring containing 500 mA at 3.0 GeV, using the data collection software XAS Collect.59 Copper and zinc K-edge data were collected on the structural biology XAS beamline 7-3 operating with a wiggler field of 2 T and employing a Si(220) double-crystal monochromator. Beamline 7-3 is equipped with a rhodium-coated vertically collimating mirror upstream of the monochromator. To minimize radiation damage and minimize thermal fluctuations contributing to the Debye-Waller factor for EXAFS analysis, samples were maintained at a temperature of approximately 10 K in a liquid helium flow cryostat (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). X-ray absorption spectra were measured as the Cu or Zn Kα fluorescence excitation spectra using a 30-element germanium array detector with analog electronics (Canberra Corporation, Meriden CT, USA)60 employing an amplifier shaping time of 0.125 μsec. To avoid problems with non-linearity of the detector due to high count-rates 3-absorption unit Ni X-ray filters (for copper samples) or 3-absorption unit Cu X-ray filters (for zinc samples) were used to preferentially absorb scattered radiation, and silver Soller- slits (EXAFS Co., Pioche NV, USA) were optimally positioned between the sample and the detector to reduce filter fluorescence registered by the detector. Incident and transmitted X-ray intensities were measured using nitrogen-filled ionization chambers. Spectra were energy-calibrated with reference to the K-edge spectrum of a copper or zinc foil, measured simultaneously with each spectrum. The lowest energy inflection of the copper K-edge was assumed to be 8980.3 eV, and 9660.7 eV for the zinc K-edge.

Successive spectra were compared using the Cu K near-edge and EXAFS spectra, which revealed increasing contribution from photoreduced copper species correlated with the duration samples were exposed to the incident beam. To minimize photoreduction of the CuII species a sample volume of 1.5 mL was prepared and loaded into a specially designed sample holder with a height of 15 mm, which allowed numerous acquisitions from areas of the frozen sample which had not previously been exposed to the beam. Furthermore, rapid CuII EXAFS data acquisition scans of c.a. 25 minutes per scan were used for a k-range of 16.2 Å−1, as opposed to ~45 minutes per scan as we have employed previously. The shorter acquisition time for CuII traded improved statistics per scan with minimizing the contribution from photoreduction. A total of 12 scans were collected, representing the minimally photoreduced CuII species, while 6 scans were collected at the same position, with the final five representative of the photoreduced species (k-range of 12 Å−1). A total of 4 scans were collected for ZnII (k-range of 14.5 Å−1), and 10 scans for the ascorbate-reduced CuI sample. Due to a monochomator crystal glitch at ~9970 eV the copper EXAFS k-range in all data was truncated to 15.75 Å−1.

EXAFS Data Analysis

The EXAFS oscillations χ(k) were quantitatively analyzed by curve-fitting using the EXAFSPAK suite of computer programs61 as described by George et al.62 Fourier transforms were phase-corrected for Cu—N backscattering. The threshold energy E0 was assumed to be 9000 eV for Cu, and 9680 eV for Zn. Ab initio theoretical phase and amplitude functions were calculated using the program FEFF version 8.25.63 FEFF multiple scattering calculations from the heavy atom framework, as defined by optimized geometries from DFT calculations (see below), used a k-range of 15.8 Å−1. Calculated scattering paths included a maximum Nleg path of 4 and an Rmax of 5.5 Å. A minimum cutoff of 10% of the mean amplitude of the largest amplitude path was used for the curved wave calculation as well as the plane-wave approximation multiple scattering paths. Scattering paths with amplitudes below this cutoff were discarded. The correlated Debye model was used to calculate approximate EXAFS Debye-Waller factors. The effect of structural deformations in the metal coordination spheres on the EXAFS spectrum was modeled from the calculated FEFF output and compared directly with other calculated output, and the EXAFS “fit parameters” therefore were not varied. For comparison of the photoreduced and minimally photoreduced data sets the Fourier transform was performed over the same k-range to produce directly comparable spatial resolution data. In each data set the multiple scattering interactions beyond 2.5 Å in the Fourier transform were backtransformed (R+Δ = 2.5 – 6 Å) and subtracted from the initial EXAFS data. This produced an EXAFS spectrum corresponding to the experimental data arising from only the primary coordination sphere (and noise), which were then directly compared.

Computational Methods

Structure Calculations

Density functional calculations were carried out with the Gaussian09, revision C.01, suite of software.64 Density functional theory is a computationally rigorous method for computing structural and electronic details of molecules, particularly for metal complexes. We anticipate bond-length accuracies of better than 0.05 Å. Open shell CuII and closed shell singlet CuI and ZnII complexes were optimized without geometry or symmetry constraints using the B3LYP hybrid functional method. Geometry optimizations of hydrated CuII, CuI and ZnII, as well as successive dehydrations with His coordination (modeled by 4-methylimidazole, MeIm) used the 6-311+G(2df,2p) basis set. Harmonic frequency calculations, were calculated for all complexes to ensure structures were at a stationary point on the potential energy surface, and calculated at the same level of theory as geometry optimizations. Structures were considered optimized when the change in energy between subsequent optimization steps fell below 0.05 J mol−1. The stabilizing effect of bulk solvation on the gas-phase-optimized structures was modeled using the integral equation formalism variant of the polarizable continuum model, IEFPCM,65 with united atom radii defining the molecular cavity and a dielectric representing water (ε = 78.39), calculated at the same level of theory as above. Single point energies for all optimized structures used the calculated energies from the B3LYP/6-311+G(2df,2p) geometry optimizations. PC Model 9.10.066 was used for some initial construction and minimization of starting structures. All molecular structures were rendered with Chemcraft. 67

Free Energy Derivation

Estimates of free energy changes in aqueous solution are constructed from calculated parameters for each of the DFT-optimized structures, as described previously.Error: Reference source not found,68 Briefly, the gas-phase enthalpy at zero Kelvin is calculated at the large basis set level, with additional terms from the harmonic frequency output to correct for the small temperature dependence in the absolute enthalpy upon going from 0 K to 298 K as well as the zero-point energy. The gas-phase entropy at 1 atm standard state is also provided in the harmonic frequency output, and is corrected for the volume change upon going from 1 atm standard state in the gas-phase to 1 M standard state for solution (–26.6 J K−1 mol−1). The free energy for each species is corrected for the stabilizing effect of solvation through the continuum solvation procedure, which describes the stabilizing electrostatic component as well as an entropic term, describing the work required to generate the molecular cavity and exclude solvent from that volume. For calculations with gain or loss of explicit solvent molecules, the free energy of solvation for a water molecule in water is taken as –16.5 kJ mol-1, which is derived from the experimental free energy of formation in the gas-phase (corrected to 1 M) and in solution (corrected to 55.5 M).

Supplementary Material

Figure 5.

DFT-optimized structure for [ZnII(MeIm)3ε(OH2)]2+, used as the initial guess structure in the best obtained fit for the ZnII EXAFS data, shown in Table 2.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an Operating Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR to GNG) and a National Institutes of Health Grant (GM065790 to GLM). MJP is supported by Fellowships from CIHR and the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (SHRF). MJP and KHN are also supported by CIHR-THRUST (CIHR-funded Training in Health Research using Synchrotron techniques) Fellowships. Research at the University of Saskatchewan was supported by a Canada Research Chair award (to GNG), the University of Saskatchewan, the Province of Saskatchewan, and the SHRF. Portions of this work were also carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource which is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE, Office of Biological and Environmental Sciences, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program. Computing resources for DFT calculations were provided by WestGrid and Compute/Calcul Canada.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemeurj.org/ or from the author.

References

- 1.Hornshaw MP, McDermott JR, Candy JM. Copper binding to the N-terminal tandem repeat region of mammalian and avian prion protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;207:621–629. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hornshaw MP, McDermott JR, Candy JM, Lakey JH. Copper binding to the N-terminal tandem repeat region of mammalian and avian prion protein: structural studies using synthetic peptides. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;214:993–999. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown DR, Qin K, Herms JW, Madlung A, Manson J, Strome R, Fraser PE, Kruck T, von Bohlen A, Schultz-Schaeffer W, Giese A, Westaway D, Kretzchmar H. The cellular prion protein binds copper in vivo. Nature. 1997;390:684–687. doi: 10.1038/37783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stöckel J, Safar J, Wallace AC, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Prion protein selectively binds copper(II) ions. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7185–7193. doi: 10.1021/bi972827k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitt-Ulms G, Ehsani S, Watts JC, Westaway D, Wille H. Evolutionary descent of prion genes from the ZIP family of metal ion transporters. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh A, Kong Q, Luo X, Petersen RB, Meyerson H, Singh N. Prion protein (PrP) knock-out mice show altered iron metabolism: a functional role for PrP in iron uptake and transport. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pushie MJ, Pickering IJ, Martin GR, Tsutsui S, Jirik FR, George GN. Prion protein expression level alters regional copper, iron and zinc content in the mouse brain. Metallomics. 2011;3:206–214. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00037j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauly PC, Harris DA. Copper stimulates endocytosis of the prion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33107–33110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watt NT, Taylor DR, Kerrigan TL, Griffiths HH, Rushworth JV, Whitehouse IJ, Hooper NM. Prion protein facilitates uptake of zinc into neuronal cells. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1134. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lima FR, Arantes CP, Muras AG, Nomizo R, Brentani RR, Martins VR. Cellular prion protein expression in astrocytes modulates neuronal survival and differentiation. J Neurochem. 2007;103:2164–2176. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roucou X, Gains M, LeBlanc AC. Neuroprotective functions of prion protein. J Neurosci Res. 2004;75:153–161. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitteregger G, Vosko M, Krebs B, Xiang W, Kohlmannsperger V, Nölting S, Hamann GF, Kretzschmar HA. The role of the octarepeat region in neuroprotective function of the cellular prion protein. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:174–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stys PK, You H, Zamponi GW. Copper-dependent regulation of NMDA receptors by cellular prion protein: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. J Physiol. 2012;590:1357–1368. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.225276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chattopadhyay M, Walter ED, Newell DJ, Jackson PJ, Aronoff-Spencer E, Peisach J, Gerfen GJ, Bennett B, Antholine WE, Millhauser GL. The octarepeat domain of the prion protein binds Cu(II) with three distinct coordination modes at pH 7.4. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12647–12656. doi: 10.1021/ja053254z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walter ED, Chattopadhyay M, Millhauser GL. The affinity of copper binding to the prion protein octarepeat domain: evidence for negative cooperativity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13083–13092. doi: 10.1021/bi060948r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Natale G, Osz K, Kállay C, Pappalardo G, Sanna D, Impellizzeri G, Sóvágó I, Rizzarelli E. Affinity, speciation, and molecular features of copper(II) complexes with a prion tetraoctarepeat domain in aqueous solution: insights into old and new results. Chemistry. 2013;19:3751–3761. doi: 10.1002/chem.201202912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garnett AP, Viles JH. Copper binding to the octarepeats of the prion protein. Affinity, specificity, folding, and cooperativity: insights from circular dichroism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6795–6802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pushie MJ, Vogel HJ. Molecular dynamics simulations of two tandem octarepeats from the mammalian prion protein: Fully Cu2+-bound and metal-free forms. Biophys. J. 2007;93:3762–3774. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.109512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pushie MJ, Vogel HJ. Modeling by assembly and molecular dynamics simulations of the low Cu2+ occupancy form of the mammalian prion protein octarepeat region: gaining insight into Cu2+-mediated beta-cleavage. Biophys J. 2008;95:5084–5091. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taubner LM, Bienkiewicz EA, Copié C, Caughey B. Structure of the flexible amino-terminal domain of prion protein bound to a sulfated glycan. J Mol Biol. 2010;395:475–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burns CS, Aronoff-Spencer E, Dunham CM, Lario P, Avdievich NI, Antholine WE, Olmstead MM, Vrielink A, Gerfen GJ, Peisach J, Scott WG, Millhauser GL. Molecular Features of the Copper Binding Sites in the Octarepeat Domain of the Prion Protein. Biochemistry. 2002;42:3991–4001. doi: 10.1021/bi011922x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson GS, Murray I, Hosszu LL, Gibbs N, Waltho JP, Clarke AR, Collinge J. Location and properties of metal-binding sites on the human prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8531–8535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151038498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pushie MJ, Ross ARS, Vogel HJ. Mass spectrometric determination of the coordination geometry of potential copper(II) surrogates for the mammalian prion protein octarepeat region. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:5659–5667. doi: 10.1021/ac070312l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones CE, Klewpatinond M, Abdelraheim SR, Brown DR, Viles JH. Probing copper2+ binding to the prion protein using diamagnetic nickel2+ and 1H NMR: the unstructured N terminus facilitates the coordination of six copper2+ ions at physiological concentrations. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:1393–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jószai V, Turi I, Kállay C, Pappalardo G, Di Natale G, Rizzarelli E, Sóvágó I. Mixed metal copper(II)-nickel(II) and copper(II)-zinc(II) complexes of multihistidine peptide fragments of human prion protein. J Inorg Biochem. 2012;112:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L, Jiang D, McDonald A, Hao Y, Millhauser GL, Zhou F. Copper redox cycling in the prion protein depends critically on binding mode. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12229–12237. doi: 10.1021/ja2045259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spevacek AR, Evans EG, Miller JL, Meyer HC, Pelton JG, Millhauser GL. Zinc drives a tertiary fold in the prion protein with familial disease mutation sites at the interface. Structure. 2013;21:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watt NT, Griffiths HH, Hooper NM. Neuronal zinc regulation and the prion protein. Prion. 2013;7:203–208. doi: 10.4161/pri.24503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quintanar L, Rivillas-Acevedo L, Grande-Aztatzi R, Gómez-Castro CZ, Arcos-López T, Vela A. Copper coordination to the prion protein: Insights from theoretical studies. Coord Chem Rev. 2013;257:429–444. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu JA, Wilson HL, Pushie MJ, Kisker C, George GN, Rajagopalan KV. The Structures of the C185S and C185A Mutants of Sulfite Oxidase Reveal Rearrangement of the Active Site. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3989–4000. doi: 10.1021/bi1001954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cotelesage JJH, Pushie MJ, Grochulski P, Pickering IJ, George GN. Metalloprotein active site structure determination: Synergy between X-ray absorption spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. J Inorg. Biochem. 2012;115:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pushie MJ, Rauk A. Computational studies of Cu(II)[peptide] binding motifs: Cu[HGGG] and Cu[HG] as models for Cu(II) binding to the prion protein octarepeat region. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8:53–65. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pushie MJ. M.Sc. Thesis. University of Calgary; AB, Canada: 2002. Computational Studies of Copper(II)-binding to Model Protein Fragments and Their Associated Redox Chemistry in an Aqueous Medium. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeşilel OZ, İlker İ, Büyükgüngör O. Three copper(II) complexes of thiophene-2,5-dicarboxylic acid with dissimilar ligands: Synthesis, IR and UV–Vis spectra, thermal properties and structural characterizations. Polyhedron. 2009;38:3010–3016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank P, Benfatto M, Hedman B, Hodgson KO. The XAS Model of Dissolved Cu(II) and Its Significance to Biological Electron Transfer. J Phys:ConferenceSeries. 2009;190:012059. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burda JV, Pavelka M, Simanek M. Theoretical model of copper Cu(I)/Cu(II) hydration. DFT and ab initio quantum chemical study. J Mol Struct (Theochem) 2004;683:183–193. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sukrat K, Parasuk V. Importance of hydrogen bonds to stabilities of copper–water complexes. Chem Phys Lett. 2007;447:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen HF. The Cambridge Structural Database: a quarter of a million crystal structures and rising. Acta Crystallogr. 2002;B58:380–388. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102003890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruno IJ, Cole JC, Edgington PR, Kessler M, Macrae CF, McCabe P, Pearson J, Taylor R. New software for searching the Cambridge Structural Database and visualising crystal structures Acta Crystallogr. 2002;B58:389–397. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102003324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guerrieri F, Minicozzi V, Morante S, Rossi G, Furlan S, La Penna G. Modeling the interplay of glycine protonation and multiple histidine binding of copper in the prion protein octarepeat subdomains. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14:361–374. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodak M, Chisnell R, Lu W, Bernholc J. Functional implications of multistage copper binding to the prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:11576–11581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903807106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalleska NF, Honma K, Sunderlin LS, Armentrout PB. Solvation of Transition Metal Ions by Water. Sequential Binding Energies of M+(H2O)x (x = 1-4) for M = Ti to Cu Determined by Collision-Induced Dissociation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:3519–3528. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mykhalichko BM, Mys'kiv MG, Davydov VN, Russ J.Inorg.Chem. 1999. 44:360. (note that the CIKRUJ entry in the CSD incorrectly lists the starting page number for this paper as p411).

- 44.Goreshnik E, Schollmeyer D, Mys'kiv M. Bis(2-methylbenzimidazole-[kappa]N1)copper(I) dichlorocuprate(I). Acta Crystallogr.,Sect.E:Struct.Rep.Online. 2004;60:m279–m281. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li XX, Fang W-H, Yang G-Y. Hydrothermal Synthesis and Crystal Structure of a New 2-D Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Wells–Dawson-Type Polyoxometalate. J.Cluster Sci. 2010;21:803–811. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shearer J, Szalai VA. The Amyloid-β Peptide of Alzheimer's Disease Binds CuI in a Linear Bis-His Coordination Environment: Insight into a Possible Neuroprotective Mechanism for the Amyloid-β Peptide. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17826–17835. doi: 10.1021/ja805940m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furlan S, Hureau C, Faller P, La Penna G. Modeling the Cu+ binding in the 1-16 region of the amyloid-β peptide involved in Alzheimer's disease. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:15119–15133. doi: 10.1021/jp102928h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kojima Y, Hirotsu K, Yamashita T, Miwa T. Conformation and Coordination Behavior of Zinc(II) Complex with Cyclo(L-methionyl-L-histidyl). Bull.Chem.Soc.Jpn. 1985;58:1894–1898. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Podlahová J, Kratochvil B, Podlaha J, Hasek J. Trigonal bipyramidal penta-aquazinc(II): crystal structure of penta-aquazinc(II) bis(3,3,3-phosphinetriyltripropionato)dizincate(II,II) heptahydrate. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1985:2393–2396. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fiolka C, Striebinger R, Walter T, Walbaum C, Pantenburg I. Tri-, Penta- und Oktaiodid-Anionen komplexer Übergangsmetall-Polyether-Kationen. Z. anorg. allg. Chem. 2009;635:855–861. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L-P, Ma J-F, Yang J, Pang Y-Y, Ma J-C. Series of 2D and 3D Coordination Polymers Based on 1,2,3,4-Benzenetetracarboxylate and N-Donor Ligands: Synthesis, Topological Structures, and Photoluminescent Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:1535–1550. doi: 10.1021/ic9019553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]