Abstract

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) is the most frequent cause of inherited intellectual disability and autism. It is caused by the absence of the fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene product, FMRP, an RNA-binding protein involved in the regulation of translation of a subset of brain mRNAs. In Fmr1 knockout (KO) mice, the absence of FMRP results in elevated protein synthesis in the brain as well as increased signaling of many translational regulators. Whether protein synthesis is also dysregulated in FXS patients is not firmly established. Here, we demonstrate that fibroblasts from FXS patients have significantly elevated rates of basal protein synthesis along with increased levels of phosphorylated mechanistic target of rapamycin (p-mTOR), phosphorylated extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2 (p-ERK 1/2) and phosphorylated p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (p-S6K1). Treatment with small molecules that inhibit S6K1, and a known FMRP target, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) catalytic subunit p110β, lowered the rates of protein synthesis in both control and patient fibroblasts. Our data thus demonstrate that fibroblasts from FXS patients may be a useful in vitro model to test the efficacy and toxicity of potential therapeutics prior to clinical trials, as well as for drug screening and designing personalized treatment approaches.

Keywords: Fragile X syndrome, FMR1, FMRP, protein synthesis, S6K1, fibroblasts

Introduction

Fragile X syndrome (FXS; MIM# 300624) is an X-linked disorder that causes cognitive impairment in males and some females that ranges from mild to severe. Many FXS patients also present with epilepsy, anxiety, attention deficit, hyperactivity, poor motor coordination and 43–67% of these patients display features of autism spectrum disorder [Wang et al., 2010]. In addition, patients with FXS often exhibit characteristic physical features that include a long narrow face, prominent ears, and macroorchidism [Goldson and Hagerman, 1992]. Mutations in the fragile X mental retardation-1 (FMR1; MIM# 309550) gene lead to the absence or a loss of function of its encoded protein, fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), which results in FXS [Devys et al., 1993]. The most common mutation in FXS is the expansion of a CGG-repeat sequence in the 5’-untranslated region of the FMR1 gene to >200 repeats (known as a full mutation, FM). FM alleles show aberrant DNA methylation and histone modifications that result in heterochromatin formation on the FMR1 promoter leading to gene silencing [Coffee et al., 2002; Sutcliffe et al., 1992]. The prevalence of the FM is approximately 1 in 7143 males and 1 in 11111 females [Hunter et al., 2014]. Given the X-linked nature of the FMR1 gene, the prevalence of FM is not equivalent to the prevalence of FXS in females, which is expected to be roughly half of what is observed in males.

FMRP is primarily an RNA-binding protein that is ubiquitously expressed during early embryonic development and highly expressed in postnatal brain and gonads [Hergersberg et al., 1995; Hinds et al., 1993]. FMRP is an extensively studied protein that is thought to be instrumental in mRNA packaging, transport and activity-dependent translation regulation [Bassell and Warren, 2008; De Rubeis and Bagni, 2010]. It is localized in somatodendritic compartments of neurons where it mainly represses the translation of target mRNAs by ribosomal stalling [Darnell et al., 2011]. Upon activity-dependent activation of pro-translation signals, FMRP-mediated repression is overcome to promote the synthesis of new proteins required for synaptic plasticity. As demonstrated in Fmr1 knockout (KO) mice, the absence of FMRP leads to an aberrant signaling phenotype downstream of several cell-surface receptors, of which metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are the most widely studied [Busquets-Garcia et al., 2013; Dolen and Bear, 2008; Louhivuori et al., 2011]. These receptors activate either the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt (PI3K-Akt) signaling to mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and/or Ras-Raf activation leading to a hypersensitized extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK 1/2) pathway [Michalon et al., 2012]. Both signaling arms converge to activate components of the eukaryotic cap-dependent translation machinery [Osterweil et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2010]. In addition, the activity of downstream effectors of mTORC1 and ERK1/2 such as p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1), eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) and S6 ribosomal protein (S6rp) have been shown to be elevated in Fmr1 KO mice [Bhattacharya et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2010]. In the past few years, several nodes in this cascade have been targeted using pharmacogenetic approaches to rescue a plethora of phenotypes expressed in FXS model mice and flies [Bhattacharya et al., 2012; Dolen and Bear, 2008; Franklin et al., 2013; Gross et al., 2010; McBride et al., 2005; Osterweil et al., 2013; Udagawa et al., 2013; Westmark et al., 2011].

The loss of FMRP is believed to cause dysregulated translation of its target mRNAs, many of which are critical for synaptic plasticity, maintaining neuronal function and regulatory control of protein synthesis [Darnell and Klann, 2013]. Indeed, studies of the Fmr1 KO mouse model of FXS show that protein synthesis rates measured in vivo are increased in many regions of the brain [Qin et al., 2005], a finding that is reproduced in hippocampal slices from Fmr1 KO mice [Muddashetty et al., 2007; Osterweil et al., 2010]. Both genetic manipulation and pharmacological treatment of Fmr1 KO mice with drugs that normalize rates of protein synthesis have been shown to correct some molecular and behavioral phenotypes [Bhattacharya et al., 2012; Henderson et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012; Michalon et al., 2012; Osterweil et al., 2013].

However, mouse models of human diseases in general, and in FXS in particular, suffer from a number of limitations. For example, the most widely used mouse model was created via targeted exon disruption (1994). Although patients with FXS might express some FMRP during early embryonic development when the gene is thought to be active [Colak et al., 2014; Eiges et al., 2007], the Fmr1 KO mice do not express FMRP at all. Furthermore, many FXS patients are mosaics either due to the presence of partially silenced alleles or premutation (PM) length (CGG repeats between 55–200) alleles that are not silenced and thus express variable levels of FMRP [Wohrle et al., 1998]. This likely has varied effects on the downstream pathways and may modulate the clinical phenotype and perhaps the therapeutic efficacy of certain drugs in these individuals.

Primary human fibroblasts are readily accessible, adherent and untransformed cells that could serve as a platform to identify novel therapeutic targets for FXS as well as identify markers to test the efficacy of targeted therapies in clinical trials. Such markers may provide quantifiable measures that could be used in conjunction with the more subjective clinical criteria that are currently used for assessing outcomes of therapeutic drug trials. However, the rates of protein synthesis and the levels of many downstream targets of FMRP identified in mice have not been examined in primary cells from FXS patients. Therefore, the goal of this study was to test whether the disease-specific molecular phenotypes observed in the brains of Fmr1 KO mice can also be seen in primary fibroblasts derived from FXS patients. Here, we report significantly elevated rates of basal protein synthesis and mTORC1 signaling in FXS fibroblasts compared to cells from unaffected individuals. Furthermore, we show that inhibition of S6K1 and the PI3K catalytic subunit p110β lowers the protein synthesis rates in these cells. Our data thus support the idea that primary fibroblasts from FXS patients can be useful for screening small molecules that may have therapeutic potential.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Culture Method

The human male fibroblasts that were used in the study are listed in Table 1. GM00357, GM05131, GM05848 and GM05185 were obtained from Coriell Cell Repositories (Camden, NJ). The cell lines CCD-1079Sk (CRL-2097) and CCD-1139Sk (CRL-2708) were from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and BJ was from Stemgent (Cambridge, MA). Fibroblast cell lines C10147, C10700 and C10259 were derived from FXS patients and have been described previously [Dobkin et al., 1996]. Fibroblasts SC176, SC207, SC194, SC148, SC197, SC126 and SC128 were derived at CHOC Children’s Research Institute, Orange, CA after patient consent forms and patient information sheets were reviewed and approved by UC Davis and CHOC Children’s Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) as described before [Stover et al., 2013]. Briefly, a 1.5 mm diameter skin punch biopsy tissue was minced into small pieces and used to establish fibroblast cultures in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (D-MEM) high glucose with GlutaMAX™, 10% Certified FBS, 1X non-essential amino acids (NEAA and 1 µM Primocin (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). As fibroblasts grew out from the explants and expanded to 50%+ confluence of the T25 surface area, they were detached from the flask using prewarmed 37°C TrypLE Express (Life Technologies) and split 1:3 to 1:4 into larger T75 culture flasks for expansion. For further experiments, all fibroblast cell lines were maintained in DMEM with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1X GlutaMax™, 1X non-essential amino acids (NEAA) and 1X Penicillin-Streptomycin (all from Life Technologies).

Table 1.

Details of control and FXS patient fibroblast cell lines used in the study

| ID number | Control/ FXS |

Age | CGG-repeat size | FMR1 mRNA # |

FMRP* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | SB | ||||||

| 1 | BJ | control | newborn | 26 | NA | 136 | 100 |

| 2 | CRL-2097 | control | newborn | 27 | NA | 94.5 | 101 |

| 3 | GM00357 | control | 3 yrs | 36 | NA | 127 | 64 |

| 4 | SC176 | control | 14 yrs | 16 | NA | 200 | 34 |

| 5 | SC207 | control | 22 yrs | 20 | NA | 133 | 44 |

| 6 | SC194 | control | 24 yrs | 18 | NA | 145 | 52 |

| 7 | SC148 | control | 56 yrs | 24 | NA | 146 | 59 |

| 8 | SC197 | control | 60 yrs | 27 | NA | 151 | 58 |

| 9 | CCD-1139 | control | 62 yrs | 25 | NA | 112 | 86 |

| 10 | C10700 | FXS | 1 yr | 53/273 | 63/463/997/1463 | 8 | |

| 11 | C10147 | FXS | 2 yrs | 89/136/273 | 97/163/430/497/997/1363 | 33 | |

| 12 | C10259 | FXS | 2 yrs | 278 | 1363 | 0.01 | |

| 13 | GM05131 | FXS | 3 yrs | 277 | 897 | 7 | |

| 14 | GM05848 | FXS | 4 yrs | 267 | ~700 | 0 | |

| 15 | SC126 | FXS | 13 yrs | 240/276 | 297/463/1463 | 2.3 | |

| 16 | SC128 | FXS | 23 yrs | 222/271/284 | 297/863 | 1.3 | |

| 17 | GM05185 | FXS | 26 yrs | 278 | 863 | 0 | |

PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SB, Southern blot.

% of GUS mRNA;

% of BJ

Quantification of FMR1 mRNA levels

Total RNA was isolated from the fibroblasts using Trizol™ reagent (Life Technologies) as per manufacturer’s recommendation. Three hundred nanograms of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using VILO™ master mix (Life Technologies) in 20 µl reaction volume. FMR1 and β-glucuronidase (GUS) mRNAs were quantified by real-time PCR using TaqMan® Fast Universal PCR master mix (Life Technologies) and TaqMan probe-primer pair (FAM™ for FMR1 and VIC® for GUS, Life Technologies) on StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR machine (Life Technologies).

Determination of CGG-repeat size

Genomic DNA was isolated from the fibroblasts by the salting out procedure [Miller et al., 1988]. The number of CGG-repeats in the FMR1 gene of control fibroblasts cells was determined by PCR as described before [Lokanga et al., 2013]. For the fibroblasts derived from FXS patients, CGG-repeat length analysis was done by PCR using AmplideX FMR1 PCR (RUO) reagents (Asuragen, Austin, TX) and capillary electrophoresis [Chen et al., 2010] according to manufacturer’s instructions as well as by Southern blot analysis as described previously [Nolin et al., 2008]. Table 1 lists the CGG-repeat size in the FMR1 gene for all of the cell lines used in this study.

Preparation of total cell lysates

For making total cell lysates, cells were scraped in the growth medium and pelleted at 250×g for 6 minutes. The cell pellet was washed with ice-cold PBS supplemented with 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 1X phosphatase inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). The pellet was then resuspended in the lysis buffer (10 mM Tris Cl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100, 1X protease inhibitor cocktail and 1X phosphatase inhibitor) and incubated on ice for 10 minutes followed by sonication to solubilize proteins and shear the DNA. The amount of protein in the lysate was quantified using Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) as per manufacturer’s protocol. Before using the lysate for western blot analyses, equal volumes of 2X Novex® Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer (Life Technologies) and 1X of NuPAGE® Sample Reducing Agent (Life Technologies) were added and the sample heated at 95°C for 10 minutes.

Antibodies and Western blot analyses

SDS-PAGE and Western blots for signaling proteins were performed as described previously [Bhattacharya et al., 2012]. Briefly, 10 µg total cell lysate was run on 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Life Technologies) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane by wet transfer (Idea Scientific Company, Minneapolis, MN) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were blocked with 0.25% Tropix®I-BLOCK™ (Life Technologies) and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse-HRP-tagged secondary antibodies (Promega, Madison, WI) at 1:8000 dilution for one hour at room temperature. The antibodies and their respective dilutions used were as follows- p-mTOR (Ser-2448) and mTOR (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) 1:1000; phospho-S6K1 (Thr-389, EMD Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA), 1:1000; total S6K1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) 1: 1000; p-ERK 1/2 (Cell Signaling Technologies), 1:2000; ERK 1/2 (Cell Signaling Technologies) 1:5000; p-eEF2 (Thr 56) and eEF2 (Cell Signaling Technologies), 1:1000; p-Akt (Ser 473) (Cell Signaling Technologies) in 3% BSA, 1:1000; Akt (Cell Signaling Technologies) in 5% BSA, 1:1000; p-S6 235/236 and 240/244 (Cell Signaling Technologies) 1:1500; S6 (Cell Signaling Technologies) 1:2000; β-tubulin and Actin (Cell Signaling Technologies) 1:8000. The blots were developed using standard or enhanced chemiluminescence detection (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and imaged using the KODAK 4000MM imaging system. Exposures were set so as to obtain signals in the linear range. Raw images were used for quantification. Bands were quantitatively analyzed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), normalized to tubulin or actin for that gel, and then normalized to total protein to express ratios of phosphorylated/total protein values. For FMRP detection, either 5 µg or 10 µg total cell lysates were run on an 4–20% Tris-Glycine polyacrylamide gel (Life Technologies) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane using 1X Transblot buffer (Quality Biological, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) with 20% methanol. The membrane was blocked for one hour with 5% blocking agent (GE Healthcare) in TBST (1X Tris buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20). The blot was incubated with 1:5000 dilution of anti-FMRP antibody overnight at 4°C (MAB2160, EMD Millipore Corporation) and subsequently probed with 1:10000 dilution of anti-β-actin antibody (ab8226, Abcam) for 1 hour at room temperature followed by secondary anti-mouse antibody (GE Healthcare). FMRP/Actin was detected using ECL™ Prime detection reagents (GE Healthcare) and imaged with FluorChem™ M (Proteinsimple, Santa Clara, CA) and quantified using AlphaView software (Proteinsimple).

Determination of rates of [3H]leucine incorporation into protein

One day prior to leucine incorporation assay, 8×104 cells/well were plated in growth medium in triplicate on a 6-well plate. For the analysis of incorporation rates, cells were incubated in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF: 125 mM NaCl; 2.5 mM KCl; 2 mM CaCl2; 1 mM MgCl2; 1.25 mM NaH2PO4; 25 NaHCO3; 10 mM D-Glucose; 0.002 of a volume of Gibco 50X Minimum Essential Medium Amino Acids Solution (Life Technologies) and then incubated in ACSF supplemented with 10 µCi/ml L-[4, 5-3H]leucine (specific activity: 250 µCi/µmol, Moravek Biochemicals and Radiochemicals, Brea, CA) at 37°C for 15 minutes. Following incubation, cells were washed three times with ice-cold ACSF and shaken in lysis buffer (40 mM Tris Cl pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.3% SDS) for 10 minutes. Proteins were precipitated from the cell lysate with 17% trichloroacetic acid (TCA, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes on ice. Samples were then centrifuged (15000×g, 4°C) and TCA removed by a single extraction with acetone. The protein pellet was dissolved in 1N NaOH, and [3H]leucine incorporation rates were determined by counting the labeled leucine in Packard 2250 CA Tri-Carb Liquid Scintillation Analyzer (Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT). Activity in the protein pellet was normalized to total protein in the cell lysates (BCA Assay, Thermo Scientific, Rockfield, IL).

Effect of small molecule inhibitors on [3H]leucine incorporation into proteins in fibroblasts

To study the effect of selective inhibitors on the rates of protein synthesis, a few changes were made to the above protocol. The [3H]leucine incorporation was done in 0.5 million cells grown on 10 cm dishes. Two dishes were used in parallel in each experiment, either with the vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO Hybri-Max, Sigma-Aldrich) or one of the two inhibitors, PF-4708671 (used at 10 µM final concentration, Sigma-Aldrich) and TGX-221 (used at 1 µM final concentration, Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX) and each experiment was repeated at least three times. Prior to incubation with [3H]leucine, fibroblast cells were rinsed twice with ACSF and pretreated for 20 minutes at 37°C with either DMSO or the inhibitor to be tested. The cells were then incubated with fresh ACSF with [3H]leucine along with DMSO or inhibitor for 15 minutes at 37°C. Following protein precipitation, the pellets were washed twice with 10% TCA and then extracted with acetone as described above.

Statistical analyses

To test whether rates of leucine incorporation significantly differed in the two genotypes, two-tailed t-tests were performed, assuming equal variances. In the inhibitor experiments, paired t-tests were performed using DMSO and treated samples from each trial. The t-tests were performed using Microsoft Excel data analysis tools. Outliers were determined using the 1.5 IQR Rule for Outliers. Statistical analyses for changes in the levels of signaling molecules were carried out by means of t-tests (assuming equal variance) in InStat statistical software (GraphPad Softwares Inc., La Jolla, CA). Correlation analyses were done using same software. Two-tailed t-tests were used to determine significance for Pearson’s correlation analyses.

RESULTS

CGG-repeat size, FMR1 mRNA and FMRP levels in control and FXS patient fibroblasts

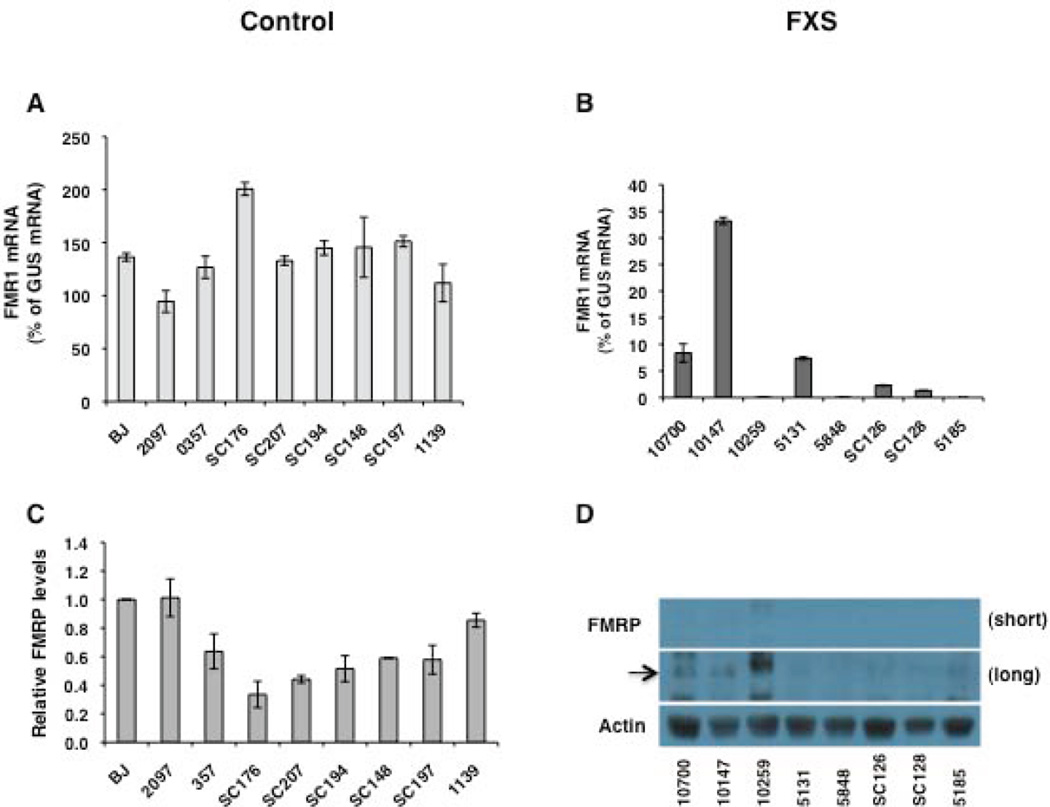

All control fibroblasts included in the present study were derived from individuals who were free of any neurological disease. Patient fibroblasts were obtained from individuals who were diagnosed with FXS based on clinical features of the disease, expression of FRAXA (fragile site, X chromosome, A site) in their lymphocytes and the presence of a FM in their FMR1 gene. Given that the CGG-repeat length and FMR1 expression can influence the disease phenotype and that somatic instability of CGG-repeats is observed in FXS cells [Lokanga et al., 2013], we first characterized the fibroblasts included in this study for the number of CGG-repeats in the FMR1 gene, as wells as FMR1 mRNA and FMRP levels (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The CGG-repeat number in the control fibroblasts, as assessed by PCR, ranged from 16 to 36 repeats, well within the normal range. All of the FXS fibroblasts had fully methylated FM alleles as assessed by Southern blot analysis. Two cell lines (C10700 and C10147) were mosaics for PM and FM length alleles and two were mosaics for only FM alleles (SC126 and SC128) (Supp. Figure S1). The FMR1 mRNA was measured by quantitative RT-PCR from three different replicates of RNA and normalized to the levels of β-glucuronidase (GUS) mRNA [Tassone et al., 2000]. In control fibroblasts, the FMR1 mRNA levels varied from 95–200% of GUS mRNA (Fig. 1A, Table 1). Given that the number of CGG-repeats can modulate FMR1 expression in the PM range [Kenneson et al., 2001; Tassone et al., 2000] and FMR1 expression varies with age [Prasad and Singh, 2008], we examined if either the donor age or the number of CGG-repeats were correlated with FMR1 mRNA levels in control fibroblasts. The FMR1 mRNA levels in the control fibroblasts were not correlated with either the age of the donor or the CGG-repeat size in the FMR1 gene (Table 2). Levels of FMR1 mRNA in FXS fibroblasts were below 7% of GUS mRNA in all cases except the two subjects with PM alleles. As expected, in these subjects FMR1 mRNA was slightly higher (8 and 33% of GUS mRNA) (Table 1, Fig. 1B). Similar to FMR1 mRNA levels, variable levels of FMRP were detected in control fibroblasts (Fig. 1C, Table 1). No significant correlation was observed between FMRP levels and CGG-repeat size (Table 2), but we found a significant negative correlation between FMRP and FMR1 mRNA levels (P < 0.02) (Table 2). This could reflect a feed back control of FMR1 expression by FMRP levels, but would need to be verified with a larger sample size. Interestingly, highest levels of FMRP were seen in fibroblasts derived from control newborns. It was previously reported that FMRP levels in dried blood samples were highest at birth, reached a nadir in the teen years, and showed a tendency to gradually increase with age in adults [LaFauci et al., 2013]. We see a similar pattern if we analyze the effect of age on FMRP levels in control fibroblasts from subjects from 14 years and older (r = 0.8284, p < 0.05). FMRP specific bands were not detected in total cell lysates of FXS fibroblasts despite double the amount of protein loaded on gels compared to controls. Upon longer exposure times, faint bands that correspond to FMRP were detected in C10700 and C10147 cells (lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 1D), likely due to the presence of PM alleles and higher levels of FMR1 mRNA. We concluded that the fibroblast cell lines included in this study conformed to the expected genetic and FMR1 expression ranges for control and FXS individuals.

Figure 1.

FMR1 mRNA and FMRP levels in fibroblasts. FMR1 mRNA levels in control (A) and FXS fibroblasts (B) are shown relative to GUS mRNA. Bars represent means ± SD of three independent determinations for each cell line. (C) Quantitation of FMRP levels in control fibroblasts. Five micrograms of total cell lysate were analyzed for FMRP levels by western blot. Data shown are an average from three experiments and shown relative to FMRP levels in BJ fibroblasts. Error bars represent ± SD (D) A representative western blot is shown for FXS fibroblasts. Ten micrograms of total cell lysate were analyzed by western blot. The black arrow indicates the position of FMRP. Short and long refers to the exposure time. The MAB2160 antibody has some cross reactivity with the FXR proteins. This results in a signal that is noticeable in patient cells on long exposures.

Table 2.

Correlation of FMR1 mRNA and FMRP levels with donor age and CGG-repeat size in control fibroblasts (n = 9).

| Variable | Pearson’s R | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| FMRP vs age | −0.2034 | 0.5996 |

| FMRP vs CGG-repeat size | 0.5019 | 0.1686 |

| FMRP vs FMR1 mRNA | −0.7524 | 0.0193 |

| FMR1 mRNA vs age | 0.0727 | 0.8524 |

| FMR1 mRNA vs CGG-repeat size | −0.5560 | 0.1201 |

Basal rates of L-[4, 5 3H]leucine incorporation in control and FXS patient fibroblasts

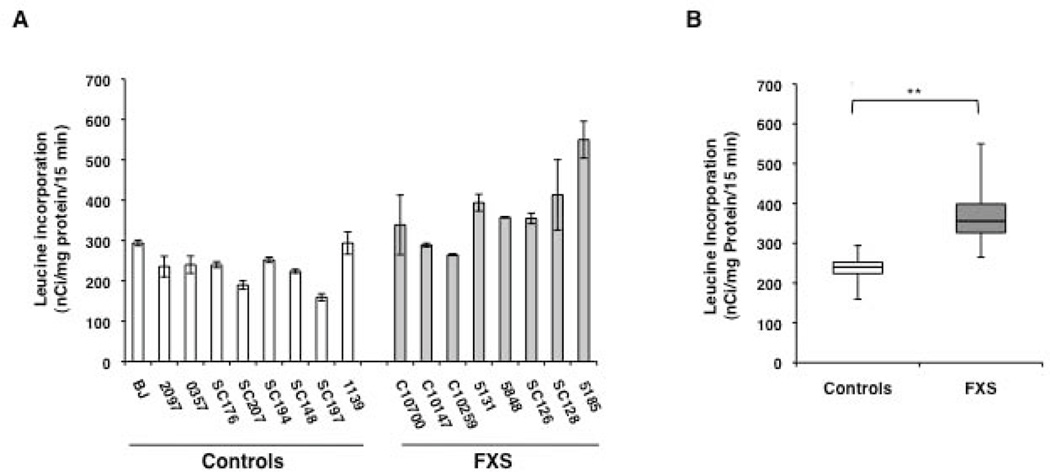

To explore if the dysregulated protein synthesis observed in Fmr1 KO mice is also a feature of the FXS patient fibroblasts, we assayed incorporation of L-[4, 5 3H]leucine into protein as a measure of basal protein synthesis rates in these cells. We optimized the assay for number of cells, concentration of tracer added and incubation time to ensure that incorporation was in the linear range. Two control and two FXS fibroblast cell lines were evaluated in triplicate in each determination. As expected, we observed variability in rates of [3H]leucine incorporation in both control and patient fibroblasts in keeping with the different genetic backgrounds of the donors (Fig. 2A). However, the average incorporation rate was 56% higher in FXS fibroblasts compared to control fibroblasts (Controls = 236.5 +/− 43.5 nCi/mg of protein/15 min; FXS = 370 +/− 87.6 nCi/mg of protein/15 min, Fig. 2 B). The difference in [3H]leucine incorporation between the two groups was highly significant (p ≤ 0.001) and is reminiscent of the elevated cerebral protein synthesis rates seen in Fmr1 KO mice in vivo [Qin et al., 2005]. To rule out the possibility that the differences in the protein synthesis levels could arise from variability in sample processing on different days, [3H]leucine incorporation rate for all the fibroblast cell lines used in the study was evaluated in a single experiment (one replicate). A similar increase (40%) in [3H]leucine incorporation rate was observed in FXS fibroblasts which was significant at p ≤ 0.0001 (Supp. Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Basal [3H]leucine incorporation rates in fibroblasts from control and FXS individuals. (A) Bars represent the average ± SEM of 3 replicates for each cell line. (B) Box plot showing [3H]leucine incorporation rates in control and FXS fibroblasts. Error bars represent maximum and minimum values. ** indicates p ≤ 0.001.

The variability in the [3H]leucine incorporation rates in control fibroblasts was not correlated with the donor age, the number of CGG-repeats in the FMR1 gene, FMR1 mRNA or FMRP protein levels (Table 3). Although we did not find a direct correlation between [3H]leucine incorporation rates with the donor age in control fibroblasts, a strong correlation was observed for FXS fibroblasts (Table 3). Because little or no FMRP was detected in the FXS fibroblasts, correlation was not done between the [3H]leucine incorporation rates and FMRP levels.

Table 3.

Correlation of protein synthesis levels with donor age, CGG-repeat size, FMR1 mRNA levels and signaling proteins in control and FXS fibroblasts.

| Variable | Pearson’s R | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Controls (n = 9) | ||

| Protein synthesis vs age | −0.2682 | 0.4853 |

| Protein synthesis vs CGG-repeat size | 0.0226 | 0.9541 |

| Protein synthesis vs FMR1 mRNA | −0.2093 | 0.5889 |

| Protein synthesis vs FMRP | 0.5343 | 0.1384 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-mTOR | 0.1478 | 0.7044 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-ERK | 0.0333 | 0.9322 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-S6K1 | 0.3519 | 0.3530 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-S6rp235/236 | −0.5666 | 0.1117 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-S6rp240/244 | 0.7032 | 0.0346 |

| Protein synthesis vs S6rp | −0.5799 | 0.1017 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-Akt | 0.3933 | 0.2950 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-eEF2 | −0.4605 | 0.2122 |

| FXS (n = 8) | ||

| Protein synthesis vs age | 0.8087 | 0.0151 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-mTOR | −0.3500 | 0.3953 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-ERK | −0.1108 | 0.7939 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-S6K1 | −0.5120 | 0.1946 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-S6rp235/236 | −0.0125 | 0.9766 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-S6rp240/244 | 0.0666 | 0.8755 |

| Protein synthesis vs S6rp | −0.2374 | 0.5713 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-Akt | −0.1759 | 0.6770 |

| Protein synthesis vs p-eEF2 | −0.0075 | 0.9858 |

Activation levels of proteins involved in translational control in fibroblasts

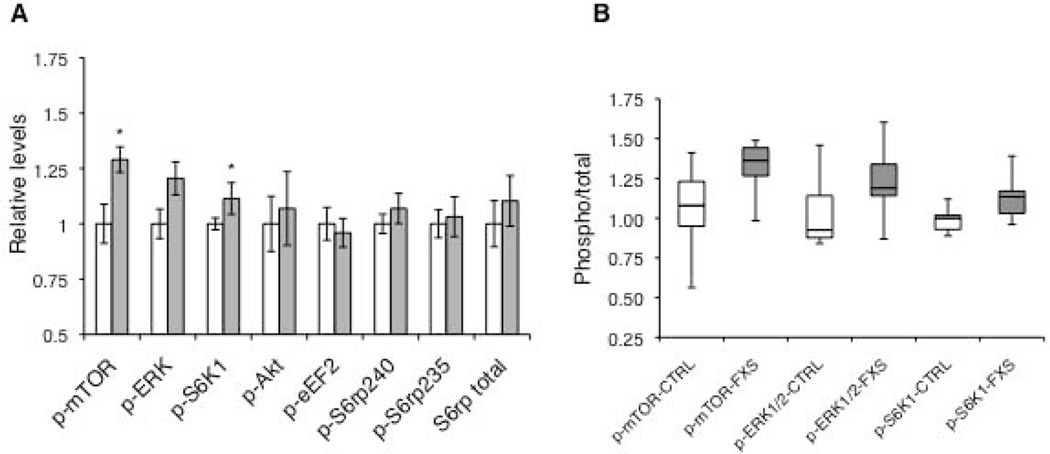

Next, we evaluated the phosphorylation states of key translational control molecules that are shown to be perturbed in studies with Fmr1 KO mice and other patient-derived samples [Bhattacharya et al., 2012; Hoeffer et al., 2012; Osterweil et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012]. Given that mTORC1 signaling is critical for cap-dependent translation and is enhanced in the Fmr1 KO mice [Sharma et al., 2010], we first examined the levels of phosphorylation of mTOR at ser2448. In this phosphorylation state, mTOR is found in association with Raptor in an active mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), which is involved in translation activation and control. We observed a significantly higher ratio of phospho/total mTOR (p-mTOR/mTOR) in FXS fibroblasts (p < 0.02, suggesting an increase in mTOR signaling (Fig. 3A and B). We also examined the activity of Akt, an upstream activator of mTORC1, that has previously been shown to be elevated in cortical synaptoneurosomes [Sharma et al., 2010] and hippocampi [Liu et al., 2012] from Fmr1 KO mice, postmortem brain tissue and lymphoblastoid cells derived from FXS patients [Gross and Bassell, 2012; Hoeffer et al., 2012]. We did not find a statistically significant difference in the levels of phosphorylated Akt (ser473) between control and FXS fibroblasts.

Figure 3.

Levels of phosphorylated signaling proteins involved in translational control. (A) Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of the phosphorylated to total ratio of each protein in controls (white bars, n = 9) and FXS cells (grey bars, n = 8). Total S6rp levels are normalized to tubulin. Levels of p-mTOR and p-S6K1 were significantly higher in cells from FXS patients (*, P ≤ 0.05) whereas those of p-ERK1/2 were higher but only approached statistical significance (p = 0.056). (B) Box plots for p-mTOR, p-ERK1/2 and p-S6K1 levels in control (white) and FXS (grey) fibroblasts. Error bars represent maximum and minimum values. Note: Representative western blots for phosphorylation states of signaling molecules are shown in Supp. Figure S3.

The translational control downstream of cell surface receptors can also be regulated by ERK1/2 signaling. Given that hypersensitized ERK1/2 has been implicated in FXS pathophysiology [Michalon et al., 2012] and increased basal phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK) levels have been observed in postmortem brain tissue from FXS patients [Wang et al., 2012], we monitored the p-ERK levels in control and FXS fibroblasts. We found a modest increase in the ratio of phospho/total ERK (p-ERK/ERK) in FXS patient cell lines compared to the controls, an effect that approached statistical significance (p = 0.056).

We then examined the levels of activated p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1), which is a common downstream effector of mTORC1 and ERK1/2 and directly regulates molecules that are components of translation initiation and elongation machinery [Magnuson et al., 2012]. Phosphorylated S6K1 (p-S6K1) is elevated in Fmr1 KO mice [Sharma et al., 2010] and genetic ablation of the S6K1 gene rescues many disease specific phenotypes in these mice [Bhattacharya et al., 2012]. Additionally, a consistent increase of p-S6K1 levels was reported in lymphocytes and postmortem brain tissue from FXS patients [Hoeffer et al., 2012]. We observed a significant (p = 0.04) increase in the ratio of phosphorylated to total S6K1 in FXS patient fibroblasts (Fig. 3A). Because S6K1 regulates translation at multiple sites, we also examined two of its downstream targets, the S6 ribosomal protein (S6rp), which is important for ribosome function, and eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2), which is critical for translation elongation [Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009]. Although we observed a minor elevation in the level of phospho-S6rp (p-S6rp) in FXS fibroblasts, the change was not statistically significant on either the 240/244 or the 235/236 site (Fig. 3A). We also examined whether total S6rp levels were elevated in FXS, which could offset any net changes in phospho- to total ratios of S6rp. In keeping with this hypothesis we detected similarly small changes in levels of total S6rp in FXS lines (Fig. 3A). The levels of p-eEF2 were also slightly decreased in FXS group as compared to controls, but the difference was not statistically significant.

We next sought to explore any relationship between the levels of signaling molecules, with age, FMR1 mRNA or FMRP levels and CGG-repeat sizes. In control fibroblasts, we found a negative correlation of p-S6K1 with donor age (Table 4). Since we had a wide range in the donor age, this correlation suggests a general decline in mTORC1-mediated signaling with age. For FXS cell lines, where the donor ages were much closer, a similar negative correlation was observed between the age and p-mTOR and p-S6K1 levels but it did not reach statistical significance (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation of activity levels of signaling proteins to various variables in control and FXS fibroblasts.

| Variable | Pearson’s R | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Controls (n = 9) | ||

| Age vs p-mTOR | −0.4397 | 0.2363 |

| Age vs p-ERK | −0.3626 | 0.3375 |

| Age vs p-S6K1 | −0.6761 | 0.0456 |

| Age vs p-eEF2 | −0.3991 | 0.2873 |

| Age vs p-S6rp235/236 | −0.4260 | 0.2529 |

| Age vs p-S6rp240/244 | −0.1003 | 0.7973 |

| Age vs p-Akt | 0.5373 | 0.1358 |

| Age vs S6rp | 0.2433 | 0.5263 |

| CGG-repeat size vs p-mTOR | 0.0784 | 0.8411 |

| CGG-repeat size vs p-ERK | 0.0257 | 0.9476 |

| CGG-repeat size vs p-S6K1 | 0.4684 | 0.2053 |

| CGG-repeat size vs p-eEF2 | −0.3855 | 0.3055 |

| CGG-repeat size vs p-S6rp235/236 | −0.2827 | 0.4611 |

| CGG-repeat size vs p-S6rp240/244 | 0.2338 | 0.5449 |

| CGG-repeat size vs p-Akt | −0.2042 | 0.5981 |

| CGG-repeat size vs S6rp | −0.0936 | 0.8106 |

| FMR1 mRNA vs p-mTOR | −0.2511 | 0.5145 |

| FMR1 mRNA vs p-ERK | −0.1647 | 0.6720 |

| FMR1 mRNA vs p-S6K1 | −0.4582 | 0.2148 |

| FMR1 mRNA vs p-eEF2 | 0.7051 | 0.0339 |

| FMR1 mRNA vs p-S6rp235/236 | 0.2583 | 0.5099 |

| FMR1 mRNA vs p-S6rp240/244 | −0.3055 | 0.4241 |

| FMR1 mRNA vs p-Akt | −0.1195 | 0.7594 |

| FMR1 mRNA vs S6rp | 0.2228 | 0.5644 |

| FXS (n = 8) | ||

| Age vs p-mTOR | −0.6653 | 0.0718 |

| Age vs p-ERK | 0.3062 | 0.4608 |

| Age vs p-S6K1 | −0.6437 | 0.0800 |

| Age vs p-S6235/236 | −0.0024 | 0.9954 |

| Age vs p-S6240/244 | −0.2805 | 0.5010 |

| Age vs S6rp | 0.1103 | 0.7949 |

| Age vs p-Akt | 0.1028 | 0.8087 |

| Age vs p-eEF2 | 0.1411 | 0.7390 |

We further analyzed the data to uncover any relationship between basal translation rates in the fibroblasts and the phosphorylation state of various translation control molecules. Although in control fibroblasts we observed a significant positive correlation between [3H]leucine incorporation rates and the levels of p-S6rp 240/244, we found no significant correlation between [3H]leucine incorporation rates in FXS fibroblasts and the phosphorylation state of any one signaling protein (Table 3). This is not surprising given the fact that leucine incorporation rates represent a combined output of all protein synthesis that is likely to be affected by multiple signaling molecules/pathways.

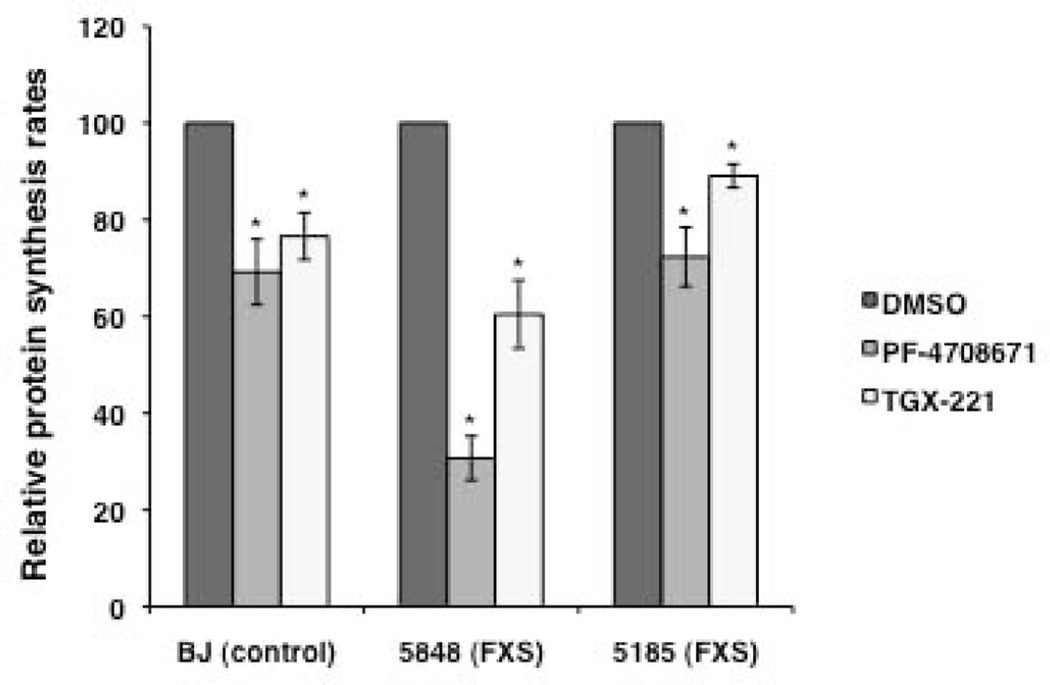

Effect of selective inhibition of S6K1 and p110β subunit of PI3K on [3H]leucine incorporation in fibroblasts

In addition to being useful for delineating disease-specific phenotypes in human cells, fibroblasts could also be useful in high-throughput screening of new drug libraries and patient-specific profiling of drug responses. To examine if these control and FXS cells could indeed be effective in realizing the latter goal, we used inhibitors of two signaling molecules to reduce protein synthesis rates in treated fibroblasts. It has been shown that genetic ablation of S6K1 can reduce protein synthesis and correct the molecular, synaptic and behavioral phenotypes in Fmr1 KO mice [Bhattacharya et al., 2012]. Increased levels of p110β protein are seen in Fmr1 KO synapses [Gross et al., 2010] and FXS patient lymphoblastoid cells [Gross and Bassell, 2012], and its inhibition with selective inhibitor TGX-221 rescues the excess protein synthesis in Fmr1 KO mice synaptoneurosomes and FXS patient lymphoblastoid cell lines [Gross and Bassell, 2012]. Here we tested the effect of selective small molecule inhibitors of S6K1 (PF-4708671) and p110β subunit of PI3K (TGX-221) on the [3H]leucine incorporation rates in control and patient fibroblasts. Cells were pre-treated with 10 µM PF-4708671 [Pearce et al., 2010] or 1 µM TGX-221 [Gross and Bassell, 2012] for 20 minutes and then used in [3H]leucine incorporation assay to measure protein synthesis rates in the presence of the drug. Both inhibitors significantly reduced protein synthesis rates in control and FXS fibroblasts (p < 0.05, Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The effect of selective inhibitors of S6K1 (PF-4708671) and p110β subunit of PI3K (TGX-221) on [3H]leucine incorporation rates in control and FXS fibroblasts. Rates are expressed as a percent of the vehicle-treated control. Bars represent means ± SEM for 3 or 4 independent replicates. *, p < 0.05. One experiment testing the inhibitory effect of TGX-221 on BJ control cells was deemed an outlier by the 1.5 IQR Rule for Outliers and was excluded from the analysis.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated whether primary human fibroblasts can be used as an in vitro model for studying the molecular phenotypes of FXS. For this, we analyzed the rates of basal protein synthesis and the levels of key translational control molecules, elevated levels of both of which have been shown to be a robust feature of the disease in Fmr1 KO mice. Furthermore, to assess the utility of these cells for evaluating compounds for their activity towards a known disease-associated phenotype, we tested specific inhibitors for two of the translational regulators known to be overactive in FXS, for their ability to reduce rates of protein synthesis in fibroblasts. Our data show that primary fibroblasts derived from FXS patients can be useful for defining the disease specific molecular phenotypes as well as for evaluating drugs prior to their use in clinical trials.

FMRP is a negative regulator of translation and its loss leads to exaggerated protein synthesis rates in the brains of Fmr1 KO mice resulting in synaptic dysfunction and altered spine morphology [Irwin et al., 2000; Santoro et al., 2012]. Many of the compounds that are currently being evaluated as potential therapeutics for FXS are believed to work by normalizing the dysregulated protein synthesis that is seen in the absence of FMRP. However, whether dysregulated protein synthesis is also a feature in FXS patients has not been clearly established. In a study of immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from two FXS patients and two controls that used a fluorescent metabolic labeling method to measure nascent protein synthesis, higher rates of synthesis were observed in patient-derived cells [Gross and Bassell, 2012]. However, in a L-[1-11C]leucine positron emission tomography study, rates of cerebral protein synthesis (rCPS) were found to be lower in FXS individuals compared with age matched controls [Qin et al., 2013]. This finding, at odds with what is seen in the Fmr1 KO mice, was likely due to the use of propofol sedation which was subsequently shown to decrease rCPS in Fmr1 KO mice [Qin et al., 2013]. It is possible therefore, that increased rCPS in human subjects with FXS was masked by the use of propofol sedation. Here we show in primary fibroblasts derived from nine controls and eight FXS patients, that basal protein synthesis rates, as measured by the incorporation of [3H]leucine, while variable, are indeed significantly elevated in primary FXS fibroblasts suggesting that human fibroblasts recapitulate the dysregulated protein synthesis phenotype seen in rodent brains [Osterweil et al., 2010; Qin et al., 2005].

The variability in [3H]leucine incorporation rates in control individuals was not correlated with the donor age, the number of CGG-repeats in the FMR1 gene, FMR1 mRNA or FMRP levels and most likely reflects genetic background variability. Because three of the control donors were over 55 years of age, while the oldest FXS patient was only 26 years old, we tested the effects of removal of the three older controls from our analyses to confirm that the differences between the two groups were not due to age differences between the groups. We found that the increases in protein synthesis rates in the FXS fibroblasts were very similar to the data shown in Figure 2 and Supp. Figure S2, and group differences between control and FXS fibroblasts remained statistically significant (p < 0.01). Hence the age-range of the donors did not influence the difference in the protein synthesis rates between control and FXS fibroblasts.

We observed a significant trend towards increased [3H]leucine incorporation rates with donor age in FXS fibroblasts. This observation is limited by the fact that the fibroblast cell lines derived from two of the youngest FXS patients were mosaic for the presence of PM alleles. These alleles were able to produce some FMRP (see Figure 1D) that could have an effect on protein synthesis rates that is age-independent. The positive correlation evaluated without these two subjects approached statistical significance (r = 0.7897, p = 0.06), suggesting that in the absence of FMRP, protein synthesis rates increase with age in fibroblasts.

In Fmr1 KO mice, the global defect in protein synthesis due to FMRP loss is thought to be compounded by exaggerated activity-dependent signaling downstream of several cell surface receptors. As mentioned above, the cascade linking these signaling receptors to translation control are the major hub kinases such as mTORC1 and ERK1/2. Given that primary fibroblasts differ from neurons in the expression profiles of cell surface transducers and other adapter proteins, we focused our search for reliable molecular markers on the conserved signaling interactors that influence translation control. We therefore evaluated the levels of activated proteins in mTORC1 and ERK pathways in control and FXS fibroblasts. We found a significant increase in the ratio of p-mTOR to total-mTOR in primary fibroblasts from FXS patients. This result differs from an earlier report on FXS leukocytes [Hoeffer et al., 2012]. We also found a significant increase in p-S6K1/S6K1 in FXS fibroblasts. For both p-mTOR/mTOR and p-S6K1/S6K1, eliminating the three older controls slightly increased the control mean values by 6% and 3%, respectively, and the observed increases in p-mTOR/mTOR and p-S6K1/S6K1 in the FXS fibroblast samples were no longer statistically significant (p = 0.08, p = 0.17 respectively). This loss of statistical significance is likely due to the decreased statistical power. A larger study in age-matched control and FXS samples is needed in order to confirm the significance of the changes in these signaling pathways.

In addition, modest increases in p-ERK1/2 were seen in FXS fibroblasts that approached statistical significance. A similar trend in p-ERK1 levels was reported for peripheral leukocytes, but no difference in the p-ERK 1/2 level was seen in postmortem frontal lobes of FXS patients [Hoeffer et al., 2012]. A second study reported increased levels of p-ERK in the frontal cortex [Wang et al., 2012]. Analysis of a larger sample size is necessary to further assess the potential of p-ERK levels as a robust biomarker.

We also examined the activation levels of other candidate molecules up- and downstream of mTORC1-S6K1 and ERK in our search for reliable markers. We did not find any candidates that were reliably dysregulated in our cohort of FXS patients. In particular, we had expected to find enhanced p-Akt levels as previously observed in peripheral blood leukocytes from FXS patients [Hoeffer et al., 2012]; the lack of a robust effect highlights cell type-specific differences in regulation of the signaling that controls translation.

Although group differences are important to ascertain disease phenotypes, inter-individual variability determines the differential response to therapy in all diseases. This aspect has become critical to the outcome of clinical trials and hence patient-stratification based on genetic criteria is becoming increasingly important. Because we had nine control and eight FXS patient fibroblasts to compare, we asked whether we could uncover any correlations between the markers we studied that could ultimately prove useful for clinical applications. We first sought to correlate [3H]leucine incorporation rates with the activation states of signaling molecules. While we found a significant positive correlation between [3H]leucine incorporation rates and p-S6rp 240/244 levels in control fibroblasts, no distinct relationship was evident in the FXS cells. This difference between the genotypes may reflect the fact that multiple signaling pathways influencing protein synthesis are dysregulated in FXS. Given that protein synthesis rates reflect a combined output of various signaling pathways and are not dependent primarily on the activity of one molecule, measurement of translation may serve as a generalized marker that can be used to test candidate molecules in these cells. Intriguingly, we found correlations between signaling molecules and other donor features like age and FMR1 mRNA levels. We found a negative relationship between age and p-S6K1 and a positive relationship between FMR1 mRNA and p-eEF2 in control fibroblasts, but not in FXS cells. This emphasizes general downregulation of pro-translational signals with increasing age. Whether this process of aging is altered between control and FXS individuals remains to be studied.

Reproduction of FXS-specific phenotypes in primary fibroblasts suggests that these unmodified cells could be a useful model system to optimize assays for high-throughput screening to identify potential therapeutic drugs that work by either restoring the expression of FMRP or by compensating for its loss. The phenotypes that we describe in this study may also be useful for identifying drugs that might benefit certain patients more than the others based on the specific alterations that are seen in their fibroblasts, leading to a more personalized approach for treatment. To this end, we have tested two small molecule inhibitors PF-4708671 and TGX-221 that specifically target translational regulators S6K1 and PI3K respectively for their ability to decrease [3H]leucine incorporation into proteins in control and FXS patient fibroblasts. We found that specific inhibition of S6K1 and PI3K activity reduced protein synthesis rates in both the control as well as FXS fibroblasts. The percent reduction in [3H]leucine incorporation rate varied between the two FXS cell lines perhaps due to the difference in ages of the donors (4 and 26 years) or to individual differences in the activity of these and/or other translational regulators. These differences may indicate a need for such evaluations before using the drugs in clinical trials.

In summary, our data suggest that primary fibroblasts may serve as a useful model system to a) screen novel drug libraries in a high-throughput format, b) by correlating patient genetic data to phenotype, allow for stratification of response to different molecular therapies available and c) finally inform future clinical trial parameters. These benefits are not limited to FXS but may be applicable to many neuropsychiatric disorders with a clear genetic basis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The fibroblasts provided by the Schwartz Laboratory were obtained in collaboration with Drs. Randi Hagerman and Flora Tassone and their groups at the UC Davis MIND Institute.

Contract grant sponsors: This study was funded by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K.U.), the National Institutes of Health Center for Regenerative Medicine (K.U.) and the National Institute of Mental Health (C.S.), the Extramural program of the National Institutes of Health [grant number NS034007 and NS047384 to E.K.], the New York State Department of People with Developmental Disabilities (C.D.), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01HD059967 to P.S.]. A.B. was the recipient of a post-doctoral fellowship from the FRAXA Research foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement. The authors declare no conflict of interest. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- Fmr1 knockout mice: a model to study fragile X mental retardation. The Dutch-Belgian Fragile X Consortium. Cell. 1994;78(1):23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60(2):201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A, Kaphzan H, Alvarez-Dieppa AC, Murphy JP, Pierre P, Klann E. Genetic removal of p70 S6 kinase 1 corrects molecular, synaptic, and behavioral phenotypes in fragile X syndrome mice. Neuron. 2012;76(2):325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busquets-Garcia A, Gomis-Gonzalez M, Guegan T, Agustin-Pavon C, Pastor A, Mato S, Perez-Samartin A, Matute C, de la Torre R, Dierssen M, et al. Targeting the endocannabinoid system in the treatment of fragile X syndrome. Nature medicine. 2013;19(5):603–607. doi: 10.1038/nm.3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Hadd A, Sah S, Filipovic-Sadic S, Krosting J, Sekinger E, Pan R, Hagerman PJ, Stenzel TT, Tassone F, et al. An information-rich CGG repeat primed PCR that detects the full range of fragile X expanded alleles and minimizes the need for southern blot analysis. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD. 2010;12(5):589–600. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffee B, Zhang F, Ceman S, Warren ST, Reines D. Histone modifications depict an aberrantly heterochromatinized FMR1 gene in fragile x syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 2002;71(4):923–932. doi: 10.1086/342931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colak D, Zaninovic N, Cohen MS, Rosenwaks Z, Yang WY, Gerhardt J, Disney MD, Jaffrey SR. Promoter-bound trinucleotide repeat mRNA drives epigenetic silencing in fragile X syndrome. Science. 2014;343(6174):1002–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1245831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N. Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron. 2009;61(1):10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, Klann E. The translation of translational control by FMRP: therapeutic targets for FXS. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16(11):1530–1536. doi: 10.1038/nn.3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C, Hung KY, Mele A, Fraser CE, Stone EF, Chen C, Fak JJ, Chi SW, et al. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell. 2011;146(2):247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rubeis S, Bagni C. Fragile X mental retardation protein control of neuronal mRNA metabolism: Insights into mRNA stability. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 2010;43(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devys D, Lutz Y, Rouyer N, Bellocq JP, Mandel JL. The FMR-1 protein is cytoplasmic, most abundant in neurons and appears normal in carriers of a fragile X premutation. Nature genetics. 1993;4(4):335–340. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin CS, Nolin SL, Cohen I, Sudhalter V, Bialer MG, Ding XH, Jenkins EC, Zhong N, Brown WT. Tissue differences in fragile X mosaics: mosaicism in blood cells may differ greatly from skin. American journal of medical genetics. 1996;64(2):296–301. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960809)64:2<296::AID-AJMG13>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolen G, Bear MF. Role for metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) in the pathogenesis of fragile X syndrome. The Journal of physiology. 2008;586(6):1503–1508. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.150722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiges R, Urbach A, Malcov M, Frumkin T, Schwartz T, Amit A, Yaron Y, Eden A, Yanuka O, Benvenisty N, et al. Developmental study of fragile X syndrome using human embryonic stem cells derived from preimplantation genetically diagnosed embryos. Cell stem cell. 2007;1(5):568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AV, King MK, Palomo V, Martinez A, McMahon LL, Jope RS. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Inhibitors Reverse Deficits in Long-term Potentiation and Cognition in Fragile X Mice. Biological psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldson E, Hagerman RJ. The fragile X syndrome. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 1992;34(9):826–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1992.tb11521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C, Bassell GJ. Excess protein synthesis in FXS patient lymphoblastoid cells can be rescued with a p110beta-selective inhibitor. Molecular medicine. 2012;18:336–345. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C, Nakamoto M, Yao X, Chan CB, Yim SY, Ye K, Warren ST, Bassell GJ. Excess phosphoinositide 3-kinase subunit synthesis and activity as a novel therapeutic target in fragile X syndrome. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30(32):10624–10638. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0402-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C, Wijetunge L, Kinoshita MN, Shumway M, Hammond RS, Postma FR, Brynczka C, Rush R, Thomas A, Paylor R, et al. Reversal of disease-related pathologies in the fragile X mouse model by selective activation of GABAB receptors with arbaclofen. Science translational medicine. 2012;4(152):152ra128. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergersberg M, Matsuo K, Gassmann M, Schaffner W, Luscher B, Rulicke T, Aguzzi A. Tissue-specific expression of a FMR1/beta-galactosidase fusion gene in transgenic mice. Human molecular genetics. 1995;4(3):359–366. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds HL, Ashley CT, Sutcliffe JS, Nelson DL, Warren ST, Housman DE, Schalling M. Tissue specific expression of FMR-1 provides evidence for a functional role in fragile X syndrome. Nature genetics. 1993;3(1):36–43. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffer CA, Sanchez E, Hagerman RJ, Mu Y, Nguyen DV, Wong H, Whelan AM, Zukin RS, Klann E, Tassone F. Altered mTOR signaling and enhanced CYFIP2 expression levels in subjects with fragile X syndrome. Genes, brain, and behavior. 2012;11(3):332–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J, Rivero-Arias O, Angelov A, Kim E, Fotheringham I, Leal J. Epidemiology of fragile X syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin SA, Galvez R, Greenough WT. Dendritic spine structural anomalies in fragile-X mental retardation syndrome. Cerebral cortex. 2000;10(10):1038–1044. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.10.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenneson A, Zhang F, Hagedorn CH, Warren ST. Reduced FMRP and increased FMR1 transcription is proportionally associated with CGG repeat number in intermediate-length and premutation carriers. Human molecular genetics. 2001;10(14):1449–1454. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFauci G, Adayev T, Kascsak R, Nolin S, Mehta P, Brown WT, Dobkin C. Fragile X screening by quantification of FMRP in dried blood spots by a Luminex immunoassay. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD. 2013;15(4):508–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZH, Huang T, Smith CB. Lithium reverses increased rates of cerebral protein synthesis in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Neurobiology of disease. 2012;45(3):1145–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokanga RA, Entezam A, Kumari D, Yudkin D, Qin M, Smith CB, Usdin K. Somatic expansion in mouse and human carriers of fragile X premutation alleles. Human mutation. 2013;34(1):157–166. doi: 10.1002/humu.22177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louhivuori V, Vicario A, Uutela M, Rantamaki T, Louhivuori LM, Castren E, Tongiorgi E, Akerman KE, Castren ML. BDNF and TrkB in neuronal differentiation of Fmr1-knockout mouse. Neurobiology of disease. 2011;41(2):469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson B, Ekim B, Fingar DC. Regulation and function of ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) within mTOR signalling networks. The Biochemical journal. 2012;441(1):1–21. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride SM, Choi CH, Wang Y, Liebelt D, Braunstein E, Ferreiro D, Sehgal A, Siwicki KK, Dockendorff TC, Nguyen HT, et al. Pharmacological rescue of synaptic plasticity, courtship behavior, and mushroom body defects in a Drosophila model of fragile X syndrome. Neuron. 2005;45(5):753–764. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalon A, Sidorov M, Ballard TM, Ozmen L, Spooren W, Wettstein JG, Jaeschke G, Bear MF, Lindemann L. Chronic pharmacological mGlu5 inhibition corrects fragile X in adult mice. Neuron. 2012;74(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic acids research. 1988;16(3):1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muddashetty RS, Kelic S, Gross C, Xu M, Bassell GJ. Dysregulated metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent translation of AMPA receptor and postsynaptic density-95 mRNAs at synapses in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27(20):5338–5348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0937-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolin SL, Ding XH, Houck GE, Brown WT, Dobkin C. Fragile X full mutation alleles composed of few alleles: implications for CGG repeat expansion. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2008;146A(1):60–65. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterweil EK, Chuang SC, Chubykin AA, Sidorov M, Bianchi R, Wong RK, Bear MF. Lovastatin corrects excess protein synthesis and prevents epileptogenesis in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Neuron. 2013;77(2):243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterweil EK, Krueger DD, Reinhold K, Bear MF. Hypersensitivity to mGluR5 and ERK1/2 leads to excessive protein synthesis in the hippocampus of a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30(46):15616–15627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3888-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LR, Alton GR, Richter DT, Kath JC, Lingardo L, Chapman J, Hwang C, Alessi DR. Characterization of PF-4708671, a novel and highly specific inhibitor of p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K1) The Biochemical journal. 2010;431(2):245–255. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S, Singh K. Age- and sex-dependent differential interaction of nuclear trans-acting factors with Fmr-1 promoter in mice brain. Neurochemical research. 2008;33(6):1028–1035. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin M, Kang J, Burlin TV, Jiang C, Smith CB. Postadolescent changes in regional cerebral protein synthesis: an in vivo study in the FMR1 null mouse. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25(20):5087–5095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0093-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin M, Schmidt KC, Zametkin AJ, Bishu S, Horowitz LM, Burlin TV, Xia Z, Huang T, Quezado ZM, Smith CB. Altered cerebral protein synthesis in fragile X syndrome: studies in human subjects and knockout mice. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2013;33(4):499–507. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro MR, Bray SM, Warren ST. Molecular mechanisms of fragile X syndrome: a twenty-year perspective. Annual review of pathology. 2012;7:219–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Hoeffer CA, Takayasu Y, Miyawaki T, McBride SM, Klann E, Zukin RS. Dysregulation of mTOR signaling in fragile X syndrome. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30(2):694–702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3696-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover AE, Brick DJ, Nethercott HE, Banuelos MG, Sun L, O'Dowd DK, Schwartz PH. Process-based expansion and neural differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells for transplantation and disease modeling. Journal of neuroscience research. 2013;91(10):1247–1262. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe JS, Nelson DL, Zhang F, Pieretti M, Caskey CT, Saxe D, Warren ST. DNA methylation represses FMR-1 transcription in fragile X syndrome. Human molecular genetics. 1992;1(6):397–400. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.6.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Taylor AK, Gane LW, Godfrey TE, Hagerman PJ. Elevated levels of FMR1 mRNA in carrier males: a new mechanism of involvement in the fragile-X syndrome. American journal of human genetics. 2000;66(1):6–15. doi: 10.1086/302720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa T, Farny NG, Jakovcevski M, Kaphzan H, Alarcon JM, Anilkumar S, Ivshina M, Hurt JA, Nagaoka K, Nalavadi VC, et al. Genetic and acute CPEB1 depletion ameliorate fragile X pathophysiology. Nature medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nm.3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LW, Berry-Kravis E, Hagerman RJ. Fragile X: leading the way for targeted treatments in autism. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2010;7(3):264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Snape M, Klann E, Stone JG, Singh A, Petersen RB, Castellani RJ, Casadesus G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway contributes to the behavioral deficit of fragile x-syndrome. Journal of neurochemistry. 2012;121(4):672–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westmark CJ, Westmark PR, O'Riordan KJ, Ray BC, Hervey CM, Salamat MS, Abozeid SH, Stein KM, Stodola LA, Tranfaglia M, et al. Reversal of fragile X phenotypes by manipulation of AbetaPP/Abeta levels in Fmr1KO mice. PloS one. 2011;6(10):e26549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohrle D, Salat U, Glaser D, Mucke J, Meisel-Stosiek M, Schindler D, Vogel W, Steinbach P. Unusual mutations in high functioning fragile X males: apparent instability of expanded unmethylated CGG repeats. Journal of medical genetics. 1998;35(2):103–111. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.