Abstract

Obesity results from the chronic imbalance between food intake and energy expenditure. To maintain homeostasis, the brainstem nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) integrates peripheral information from visceral organs and initiates reflex pathways that control food intake and other autonomic functions. This peripheral-to-central neural communication occurs through activation of vagal afferent neurons which converge to form the solitary tract (ST) and synapse with strong glutamatergic contacts onto NTS neurons. Vagal afferents release glutamate containing vesicles via three distinct pathways (synchronous, asynchronous, and spontaneous) providing multiple levels of control through fast synaptic neurotransmission at ST-NTS synapses. While temperature at the NTS is relatively constant, vagal afferent neurons express an array of thermosensitive ion channels named transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Here we review the evidence that TRP channels pre-synaptically control quantal glutamate release and examine the potential roles of TRP channels in vagally mediated satiety signaling. We summarize the current literature that TRP channels contribute to asynchronous and spontaneous release of glutamate which can distinctly influence the transfer of information across the ST-NTS synapse. In other words, multiple glutamate vesicle release pathways, guided by afferent TRP channels, provide for robust while adaptive neurotransmission and expand our understanding of vagal afferent signaling.

Keywords: vagus, solitary tract, vesicle release, synaptic, calcium, autonomic reflexes, TRPV3, TRPM3, spontaneous, asynchronous, synchronous, temperature

INTRODUCTION

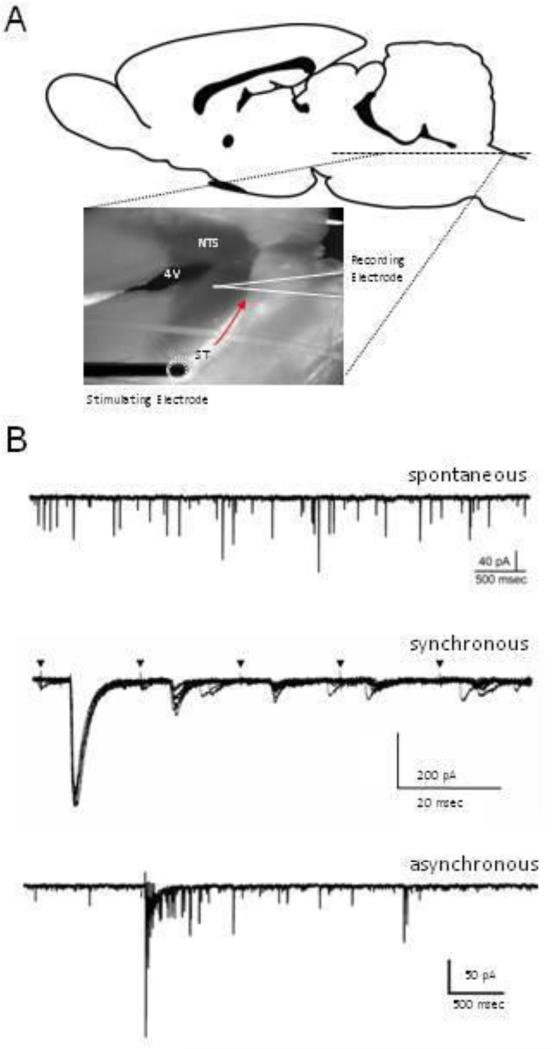

Primary vagal afferent neurons provide a direct neural pathway through which the status of peripheral organ systems (including the heart, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract) and satiety signals are relayed to the brain [1-3]. Vagal afferent neurons convey a broad range of stimuli which vary by information types, time-frames, and relative physiological urgencies. As a result, information transfer must be at once reliable and precise while maintaining plasticity to match autonomic function to the physiological state. To control information transfer, vagal afferents release the fast excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate via three distinct pathways: synchronous, asynchronous, and spontaneous (Figure 1) [4]. The interplay between these multiple complementary vesicle release pathways allows for robust and precise information transfer which is also adaptable and plastic to changing physiological states.

Figure 1. Summary of NTS slice electrophysiology and forms a of glutamate release pathways.

A) Schematic representation of a horizontal brainstem slice and location of recording electrode. Horizontal orientation of the slice maintains a long section of the solitary tract (ST) allowing for selective stimulation of primary afferent endings. B) Sample post-synaptic electrophysiology recordings representing modes of vesicle release. Spontaneous (top) occurs independently of depolarization, synchronous (middle) results in depolarization, and subsequent activation causes frequency dependent depression (FDD) in synchronous EPSC amplitude. Asynchronous (bottom) is characterized by an increase frequency of quantal vesicle release following depolarization and synchronous glutamate release.

Vagal afferent neurons are broadly divided into myelinated A-fibers, lightly myelinated Aδ-fibers, and unmyelinated C-fibers based off conduction velocity and histological analysis. C-fibers compose the majority of neurons in the vagus and robustly express the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) ion channel thus conveying their sensitivity to capsaicin lesion [5]. Centrally vagal afferents converge with the facial (VII) and glossopharyngeal (IX) nerves to form the solitary tract (ST) bundle and innervate second-order NTS neurons [2]. Afferent innervation onto second-order NTS neurons is limited relative to central synapses; with as few as 1-5 discrete primary afferent inputs converging [6]. Further, convergent inputs are completely segregated based on their expression of TRPV1 or not [7]. This organizational schema allowed for the observation that the presence of TRPV1 in the central terminals predicts facilitated forms of quantal glutamate release; including higher frequencies of spontaneous and asynchronous quantal release compared to afferents lacking TRPV1 [4]. This activity-dependent asynchronous glutamate release prolongs the period of action potential driven release (from milliseconds to seconds) and extends the postsynaptic excitatory period despite frequency dependent depression (FDD) of synchronous glutamate release [4]. Furthermore, TRPV1, and likely other thermosensitive TRP channels, provide temperature sensitive calcium conductances which largely determine the rate of spontaneous vesicle fusion [8, 9]. We speculate these additional vesicle release pathways contribute to the relative strength of C-fibers in activating autonomic reflex pathways, including those that control food intake and energy balance.

Here, we discuss the plasticity of vagal afferent signaling within the context of food intake and energy balance. We will discuss the different forms of glutamate release which define the adaptive nature of vagal afferent signaling and summarize evidence that thermosensitive TRP channels guide glutamate release pathways. Consideration of peripheral and central peptides and their effects on satiation through these glutamate release pathways will be given. In short, complementary vesicle release pathways, segregated innervation of vagal afferents, and the presence of highly adaptable temperature sensitive TRP ion channels allow vagal afferent signaling to be predictive and reactive in order to efficiently maintain energy homeostasis. By elucidating the cellular mechanisms that enable the adaptive nature of vagal afferent, we hope to gain a better understanding of vagal afferent control of food intake and energy balance.

GLUTAMATE RELEASE PATHWAYS

Spontaneous vesicle fusion and release

Spontaneous vesicle fusion is a stochastic but regulated process of neurotransmitter release which occurs independently of action-potential depolarization of the terminal (Figure 1B, top panel) [10]. Individual vesicles fuse and are released probabilistically over time from pre-synaptic active zones. The average peak current amplitude generated by the glutamate released from single vesicles acting at the postsynaptic receptors represents the fundamental unit or quantum (q) of neurotransmission. Because the charge transfers of discrete quanta are small they are often recorded as a surrogate for action-potential release pathways and in the past not considered important signaling events by themselves [11]. However, it is now generally appreciated that spontaneous neurotransmission can be important for neuronal communication during development, for setting synapse gain sensitivity, and in the trophic maintenance of the synaptic contacts [11]. The frequency of spontaneous release from vagal afferent endings is robust enough to be determinant of postsynaptic membrane excitability by itself and directly under the control of thermo-sensitive TRP channels [9].

At ST-NTS synapses the frequency of spontaneous vesicle release is largely driven by calcium influx via thermosensitive TRP channels [9]. The presence of TRPV1 in ST primary afferents predicts relatively high spontaneous frequency, while pharmacological antagonism of TRPV1 reduces overall temperature sensitivity of the spontaneous release pathway particularly at the highest temperatures recorded (~40°C) [4, 9]. This phenomenon has also been observed in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) [12]. In TRPV1 KO animals we found that frequency of spontaneous release was indistinguishable from control animals including during temperature ramps from 33-37°C [8]. The observation that spontaneous frequency is maintained at warm temperatures and is still reactive to temperature steps indicates that additional temperature sensitive mechanisms are participating in addition to TRPV1. In our recent paper we report functional expression of TRPV3 and TRPM3 ion channels; plausible candidates for the maintenance of temperature driven spontaneous release at warm physiological temperatures. These temperature driven changes may be relevant in detecting a number of physiological processes that alter internal temperatures such as post prandial thermogenesis [13], circadian temperature changes [14], or fever.

Synchronous vesicle fusion and release

Synchronous glutamate release is a tightly regulated process by which an action potential evokes the coordinated release of multiple glutamate vesicles into the synaptic cleft [15]. At ST-NTS synapses this precise timing is accomplished by the close approximation of N-type voltage activated calcium channels with primed vesicles positioned at the membrane [16]. As a result synchronous vesicle release provides a large excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) from the afferent to the postsynaptic neuron and ensures high fidelity synaptic throughput [17].

The parameters of vesicle release that affect EPSC can be demonstrated through the equation:

where ‘N’ represents the number of available release sites, ‘q’ the quantal size of single vesicles as represented by spontaneous release (see above), and ‘Pr’ the probability of release [18]. The probability of release (Pr) is the probability that a vesicle will fuse and release neurotransmitters for a given presynaptic action potential. Compared to most central synapses, vagal afferents exhibit a high ‘Pr’ under physiological conditions (70-90%), resulting in nearly complete release of docked/primed vesicles following an action-potential [19, 20]. This helps to ensure a high ratio of presynaptic to postsynaptic action-potential throughput, particularly at relatively low frequencies of firing. In contrast, high frequency activation results in a pronounced decrease in afferent glutamate release, a process known as frequency dependent depression (FDD) (Figure 1B, middle panel) [21]. FDD is the result of vesicle release out pacing the vesicle mobilization to the membrane. This produces a temporary, functional, loss of vesicle release sites ‘N’ because fewer vesicles are docked and primed at the presynaptic membrane [18]. While synchronous release is steeply calcium dependent, including both ‘Pr’ and vesicle mobilization, calcium influx via TRP channels does not appear to impact these parameters; consistent with localized micro- and nanodomain calcium determined by voltage activated calcium channels. However, TRP channel derived calcium is determinant of quantal vesicle release as described above for spontaneous release and contributes to asynchronous vesicle mobilization reviewed next.

Asynchronous vesicle fusion and release

As with synchronous release, asynchronous neurotransmitter release is action-potential dependent, but distinguishes itself by being only loosely coordinated with depolarization [15]. While synchronous release is a large and immediate release of vesicles, from vagal afferents asynchronous is characterized by a relatively long period (up to a few seconds) of stochastic release of individual quanta which occurs after the action potential is terminated (Figure 1B, lower panel) [4, 7]. Asynchronous release from vagal afferents is dependent a serial transduction of events including terminal depolarization, opening of voltage activated calcium channels with calcium influx, and synchronous vesicle fusion and release [4]. As a consequence, disruption of any of these processes disrupts both synchronous and asynchronous release. However, not all vagal afferent synapses exhibit asynchronous release but do share common synchronous release mechanisms. These findings lead to the observation that reduction of TRPV1 signaling, either pharmacologically or with temperature, selectively diminished asynchronous but not synchronous glutamate release [4].

In the unmyelinated C- and lightly myelinated Aδ-fibers of the ST-NTS synapses, asynchronous release represents an unusually high proportion of neurotransmission, in some cases making up nearly half of total vesicle release [4, 7, 8]. In rats the asynchronous profile decays with a biexponential fit suggestive of perhaps multiple processes determining the prolonged release. However, in mice the asynchronous release decays with a single exponential and as such is much faster. Despite these differences this form a neurotransmission is a major signaling component and drives prolonged postsynaptic membrane excitability and spiking [4]. Understanding the specific mechanisms common and selective to synchronous and asynchronous release should allow for the modification of one process or the other independently. So far, only attenuation of TRP channel function has allowed us to alter asynchronous release and not synchronous; although it is likely additional mechanism will be revealed with future experiments. At other synapses asynchronous release is the result of differences in presynaptic calcium channels, synaptotagmin subtypes with varying calcium affinities, and expression of specific synapsin proteins [22-24]. Investigation in to these possibilities will likely clarify our understanding of asynchronous glutamate release at vagal afferent neurons.

VAGAL AFFERENT ‘TRP’ CHANNEL EXPRESSION

In this review, we present evidence to suggest that presence of thermosensitive TRP channels in vagal afferents contributes to the neurocircuitry of feeding by maintaining adaptable synaptic transmission at the ST-NTS synapse. TRPV1 is expressed at the terminals of vagal afferent terminals specifically in C-type fibers and provides a unique form of asynchronous vesicular release as well as temperature sensitive spontaneous vesicular release [4, 9, 25]. Recent findings that involve pharmacological and genetic deletion of TRPV1 also implicate other thermosensitive TRP channels in this process.

We now appreciate there are likely more TRP channels, other than TRPV1, controlling neurotransmission through asynchronous and spontaneous glutamate release [8]. Table 1 reports the extensive expression of TRP channels identified in vagal afferent neurons [26-31]. New functional evidence from our laboratory shows that with pharmacological blockade and genetic deletion of TRPV1, some asynchronous release and temperature driven spontaneous release of glutamate is maintained at ST-NTS synapses [8]. These findings suggest additional thermosensitive TRP channels as potential candidates for further study of glutamatergic neurotransmission at ST-NTS synapses. We highlight two potential candidates TRP channels that may be participating in vagal neurotransmission; TRPV3 and TRPM3.

Table 1.

Summary of TRP channel expression in nodose ganglia.

| TRP | In Nodose Ganglia (NG) | Methods of detection ‘X’ indicates present; ‘n/a’ denotes not known |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | x | Glazebrook et al., 2005 - immunoreactivity present in soma of rat NG, also distributes to peripheral axons and mechanosensory terminals; Elg et al., 2007 - RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression; Zhao et al., 2010 - RT-PCR rat |

| C2 | x | Elg et al., 2007 - RT-PCR shows higher expression in embryonic stages of mouse development compared to postnatal and adult stages |

| C3 | x | Glazebrook et al., 2005 - immunoreactivity present in soma of rat NG, also distributes to peripheral axons and mechanosensory terminals; Elg et al., 2007- RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression; Zhao et al., 2010 - RT-PCR rat |

| C4 | x | Glazebrook et al., 2005 - immunoreactivity present in soma of rat NG, also distributes to peripheral axons and mechanosensory terminals; Elg et al., 2007- RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression |

| C5 | x | Glazebrook et al., 2005 - immunoreactivity present in soma of rat NG, also distributes to peripheral axons and mechanosensory terminals; Zhao et al., 2010 - RT-PCR rat |

| C6 | x | Glazebrook et al., 2005 - immunoreactivity present in soma of rat NG; Elg et al., 2007-RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression; Zhao et al., 2010 - RT-PCR rat |

| C7 | x | Glazebrook et al., 2005 - immunoreactivity present in soma of rat NG; Elg et al., 2007 - RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression |

| V1 | x | Zhang et al., 2004 - RT-PCR mouse and immunohistochemistry in mouse and guinea pig; Zhao et al., 2010 - RT-PCR rat |

| V2 | x | Zhang et al., 2004 - RT-PCR mouse and immunohistochemistry in mouse and guinea pig; Zhao et al., 2010 - RT-PCR rat |

| V3 | x | Zhang et al., 2004 - RT-PCR mouse; Zhao et al., 2010 - RT-PCR rat |

| V4 | x | Zhang et al., 2004 - RT-PCR mouse; Zhao et al., 2010 - RT-PCR rat |

| V5 | n/a | |

| V6 | n/a | |

| M1 | n/a | |

| M2 | x | Staaf et al., 2010 - RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression |

| M3 | x | Staaf et al., 2010 - RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression |

| M4 | x | Staaf et al., 2010 - RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression |

| M5 | x | Staaf et al., 2010 - RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression with higher expression at embryonic versus adult stages |

| M6 | x | Staaf et al., 2010 - RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression |

| M7 | x | Staaf et al., 2010 - RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression |

| M8 | x | Staaf et al., 2010 - RT-PCR in mouse showing developmental expression; Zhang et al., 2004 - RT-PCR mouse; Zhao et al., 2010 - RT-PCR rat |

| A1 | x | Zhao et al., 2010- RT-PCR rat |

| P1 | n/a | |

| P2 | n/a | |

| P3 | n/a | |

| P5 | n/a | |

| ML1 | n/a | |

| ML2 | n/a | |

| ML3 | n/a | |

| N1 | x | Zhang et al., 2004 - RT-PCR mouse |

TRPV3

The ion channel TRPV3 is member of the TRP vanilloid subfamily and highly homologous to TRPV1 [32]. Characterized as a thermosensitive calcium channel found in keratinocytes, TRPV3 is also expressed in discrete brain regions and primary sensory afferents also expressing TRPV1 [33-37] including primary vagal afferents [31]. Because of the sequence homology with TRPV1, co-localization on the same chromosome, and similar expression profiles, work has begun to explore the interactions between TRPV3 and TRPV1.

Alone, or perhaps in heteromeric confirmation with TRPV1, TRPV3 provides a temperature stimulated calcium conductance in the same temperature range that drives spontaneous release independently of TRPV1 (33-39°C) [38, 39]. Preliminary electrophysiological studies using transgenic TRPV1 KO mice suggest that TRPV3 may drive some of the remaining asynchronous release at the ST-NTS synapse independent of TRPV1 and maintain the temperature sensitivity of spontaneous release. Previous reports [31] also support the presence of TRPV3 and TRPV1 co-expression in vagal afferent neurons. Ethyl vanillin (EVA), a TRPV3 agonist [40], dose-dependently increases calcium in a subpopulation of TRPV1 positive neurons. Furthermore, when TRPV1 and TRPV3 are cloned into HEK cells, the proteins spontaneously assemble as hetero-tetramer subunits [36]. As such, we have reason to predict that TRPV3 will also influence TRPV1-dependent asynchronous and spontaneous glutamate release in native synapses.

TRPM3

TRPM3 is a relatively new and under investigated member of the melastatin family of TRP channels [41]. It is of interest to us because like TRPV1, it passes calcium and is highly thermosensitive in the physiological range for spontaneous glutamate release. In somatosensory neurons TRPM3 is crucial for temperature detection with TRPM3 KO mice showing a clear decrease in their avoidance of noxious heat [42]. Between all the TRP channels, TRPM3 has the largest number of splice variants [43], which results in a range of functionality. However, the majority conduct calcium and are strongly and specifically activated by the steroid pregnenolone sulfate [41]. Additionally, almost all vagal afferent neurons that express TRPM3 co-express TRPV1 in their membrane [8], suggesting that they will likely share some functional role in the control of glutamate release. With this in mind, it is probable that their thermosensitive nature and passage of calcium facilitates part of the asynchronous and synchronous neurotransmitter release in the ST-NTS, along with TRPV1 and TRPV3.

SYNAPTIC PLASTICITY and SATIETY SIGNALING

Vagal afferent to NTS glutamatergic synaptic transmission maintains homeostasis of many physiological processes, including those that control food intake and energy balance. To maintain energy homeostasis, the neuronal circuits that convey peripheral information are matched with hormonal, nutrient, and neuronal signals of the organism. This neurocircuitry is robust and precise in its ability to transmit signals, yet the fidelity of these signals must change from moment to moment in order to adapt to a changing internal environment and the current needs of the organism. Similar considerations are also present in the neurocircuitry of the hypothalamus and may inform NTS processing [44, 45]. Here, we discuss the cellular mechanisms present at the ST-NTS synapse in order to maintain the synaptic plasticity crucial to efficient satiety signaling.

Vagal afferent signaling must be robust and precise in the initiation of autonomic reflex pathways and the control of feeding. These characteristics are seemingly in opposition to synaptic plasticity at the ST-NTS synapse. The ST-NTS synapse undergoes changes in synaptic strength and neurotransmission via presynaptic calcium influx, a key regulator in short-term synaptic plasticity [46]. These rapid functional changes ensure that vagal afferent signaling can quickly adapt to changes in the environment and the internal milieu of the organism. The probabilistic nature of glutamate release coupled with the multiple vesicle release pathway enable vagal afferents to maintain these opposing traits.

Table 2 provides a summary of the peptides secreted peripherally (from the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and adipose tissue) and centrally (from the hypothalamus) whose actions converge at the NTS [19, 20, 47-52]. The information from these converging signals is integrated at the brainstem for control of food intake and energy balance. Some of these peptides contribute to efficient vagal afferent signaling by directly or indirectly modulating glutamate release at the ST-NTS synapse. For instance, peripheral peptides such as cholecystokinin (CCK) and central peptides such as oxytocin act on second order NTS neurons to enhance vagally mediated satiety signaling [20, 47]. At the cellular level, they exert their actions by increasing synchronous, asynchronous, and spontaneous glutamate release from vagal afferent terminals. In doing so, they contribute to the adaptive nature of neurotransmission across the ST-NTS synapse and efficiency of vagal afferent signaling.

Table 2.

Actions of peripheral and central peptides.

| Peripheral | Synchronous | Asynchronous | Spontaneous |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCK [47, 48] | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Leptin [51] | ↓ | ? | ↓ |

| Ghrelin [49] | ↓ | ? | ↓ |

| GLP1 | ? | ? | ? |

| Gastrin | ? | ? | ? |

| PYY | ? | ? | ? |

| Amylin | ? | ? | ? |

| Insulin via TRPV1 | ? | ? | ↑ |

Following synchronous neurotransmitter release, asynchronous release can persist for many seconds after an action potential and plays an important role in the plasticity of the synapse. At specialized synapses where asynchronous release is prominent, the nature of vesicle release is transformed allowing for more nuanced neurotransmission and coincidence detection [15]. Pre-synaptic asynchronous release contributes to synaptic plasticity in many specialized synapses, including the ST-NTS synapse. Because of asynchronous release, vagal afferent neurons have the ability to transform information transfer by extending the excitatory period after an action potential depolarization via elevation of neurotransmitter release in addition to synchronous release. Thus, facilitation of neurotransmission by asynchronous release at this synapse contributes to plastic changes at this synapse that fine tune the signal from vagal afferent neurons through amplification or sensitization of the original stimulus. In contrast to asynchronous release, pre-synaptic spontaneous release does not depend on action potentials but plays an important role in neurotransmission at the ST-NTS synapse. It does so by setting the tone of neurotransmission. In fact, this form of release has been implicated in synaptic plasticity at many specialized synapses through synaptic stabilization [15].

Thermosensitive TRP channels (particularly TRPV1) are sources of asynchronous and spontaneous release at the ST-NTS synapse. By increasing pre-synaptic calcium influx, TRPV1 dramatically transforms information transfer emanating from vagal afferent neurons by extending the excitatory period and increasing synaptic strength [4]. Without this property, the ST-NTS synapse loses efficiency of information transfer from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain. We postulate that redundancy in TRP channels expression accounts for a large portion of asynchronous and spontaneous release maintaining the multiple vesicle release pathways and fast neurotransmission at the ST-NTS synapse [8]. Thus, the presence of TRP channels endows the ST-NTS synapse with nuance and plasticity so that satiety signaling can adapt efficiently to a changing environment.

CONCLUSIONS and FUTURE DIRECTIONS

To maintain homeostasis of energy stores, vagal afferents carry satiety information to the central nervous system. To do so efficiently, it undergoes continuous change. Vagal afferent to NTS neurotransmission is at once robust and reliable while maintaining the ability to adapt to changing internal environments and physiological states. This balance of traits is a result of the segregation of primary afferent innervation, presence of temperatures sensitive TRP channels, and multiple forms of synaptic vesicles release. Our understanding of how TRP channels signal satiation through control of glutamate release is still in its infancy. Although other labs have shown that many TRP channels are expressed in vagal afferent neurons, we have yet to elucidate their functional roles at the level of the ST-NTS synapse. We believe that further investigation on TRP channels and their role on glutamate release will lead to a greater understanding of the cellular mechanisms of satiety signaling. We predict that future investigation in this area will reveal the adaptive nature of information transfer through glutamate release from vagal afferent neurons.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Vagal afferents initiate homeostatic reflexes via strong glutamatergic synapses.

Vagal afferents release glutamate via multiple pathways.

Central thermosensitive TRP channels control quantal forms of glutamate release.

TRP channels and multiple release pathways allow for robust but plastic signaling.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, DK092651.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This manuscript is based on work presented during the 2013 Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Ingestive Behavior, July 30 – August 3, 2013.

Reference List

- 1.Berthoud HR. The vagus nerve, food intake and obesity. Regul. Pept. 2008;149:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loewy AD. Central autonomic pathways. In: Loewy AD, Spyer KM, editors. Central regulation of autonomic functions. Oxford; New York: 1990. pp. p88–103. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saper CB. The central autonomic nervous system: Conscious visceral perception and autonomic pattern generation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;25:433–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.032502.111311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Fawley JA, Smith SM, Andresen MC. Primary afferent activation of thermosensitive TRPV1 triggers asynchronous glutamate release at central neurons. Neuron. 2010;65:657–669. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holzer P. Capsaicin: Cellular targets, mechanisms of action, and selectivity for thin sensory neurons. Pharmacol. Rev. 1991;43:143–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDougall SJ, Peters JH, Andresen MC. Convergence of cranial visceral afferents within the solitary tract nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:12886–12895. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3491-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Fawley JA, Andresen MC. TRPV1 marks synaptic segregation of multiple convergent afferents at the rat medial solitary tract nucleus. PLoS. One. 2011;6:e25015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenwick AJ, Wu SW, Peters JH. Isolation of TRPV1 independent mechanisms of spontaneious and asynchronous glutamate release at primary afferent to NTS synapses. Frontiers in Autonomic Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shoudai K, Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Fawley JA, Andresen MC. Thermally active TRPV1 tonically drives central spontaneous glutamate release. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:14470–14475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2557-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kavalali ET, Chung C, Khvotchev M, Leitz J, Nosyreva E, Raingo J, Ramirez DM. Spontaneous neurotransmission: an independent pathway for neuronal signaling? Physiology. (Bethesda. ) 2011;26:45–53. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00040.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung C, Kavalali ET. Seeking a function for spontaneous neurotransmission. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:989–990. doi: 10.1038/nn0806-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anwar IJ, Derbenev AV. TRPV1-dependent regulation of synaptic activity in the mouse dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve. Frontiers in Autonomic Neuroscience. 2013;7:238. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griggio MA, Richard D, Leblanc J. The involvement of the sympathetic nervous system in meal-induced thermogenesis in mice. Int. J. Obes. 1991;15:711–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buhr ED, Yoo SH, Takahashi JS. Temperature as a universal resetting cue for mammalian circadian oscillators. Science. 2010;330:379–385. doi: 10.1126/science.1195262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaeser PS, Regehr WG. Molecular Mechanisms for Synchronous, Asynchronous, and Spontaneous Neurotransmitter Release. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013 doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendelowitz D, Yang M, Reynolds PJ, Andresen MC. Heterogeneous functional expression of calcium channels at sensory and synaptic regions in nodose neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;73:872–875. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey TW, Hermes SM, Andresen MC, Aicher SA. Cranial visceral afferent pathways through the nucleus of the solitary tract to caudal ventrolateral medulla or paraventricular hypothalamus: Target-specific synaptic reliability and convergence patterns. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:11893–11902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2044-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clements JD, Silver RA. Unveiling synaptic plasticity: a new graphical and analytical approach. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey TW, Jin Y-H, Doyle MW, Smith SM, Andresen MC. Vasopressin inhibits glutamate release via two distinct modes in the brainstem. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:6131–6142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5176-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Kellett DO, Jordan D, Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Andresen MC. Oxytocin enhances cranial visceral afferent synaptic transmission to the solitary tract nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:11731–11740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3419-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doyle MW, Andresen MC. Reliability of monosynaptic transmission in brain stem neurons in vitro. J. Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2213–2223. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hefft S, Jonas P. Asynchronous GABA release generates long-lasting inhibition at a hippocampal interneuron-principal neuron synapse. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1319–1328. doi: 10.1038/nn1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medrihan L, Cesca F, Raimondi A, Lignani G, Baldelli P, Benfenati F. Synapsin II desynchronizes neurotransmitter release at inhibitory synapses by interacting with presynaptic calcium channels. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1512. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun J, Pang ZP, Qin D, Fahim AT, Adachi R, Sudhof TC. A dual-Ca2+-sensor model for neurotransmitter release in a central synapse. Nature. 2007;450:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nature06308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doyle MW, Bailey TW, Jin Y-H, Andresen MC. Vanilloid receptors presynaptically modulate visceral afferent synaptic transmission in nucleus tractus solitarius. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:8222–8229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buniel M, Wisnoskey B, Glazebrook PA, Schilling WP, Kunze DL. Distribution of TRPC channels in a visceral sensory pathway. Novartis. Found. Symp. 2004;258:236–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elg S, Marmigere F, Mattsson JP, Ernfors P. Cellular subtype distribution and developmental regulation of TRPC channel members in the mouse dorsal root ganglion. J. Comp Neurol. 2007;503:35–46. doi: 10.1002/cne.21351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glazebrook PA, Schilling WP, Kunze DL. TRPC channels as signal transducers. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:125–130. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1468-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staaf S, Franck MC, Marmigere F, Mattsson JP, Ernfors P. Dynamic expression of the TRPM subgroup of ion channels in developing mouse sensory neurons. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2010;10:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L, Jones S, Brody K, Costa M, Brookes SJ. Thermosensitive transient receptor potential channels in vagal afferent neurons of the mouse. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G983–G991. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00441.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao H, Sprunger LK, Simasko SM. Expression of transient receptor potential channels and two-pore potassium channels in subtypes of vagal afferent neurons in rat. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G212–G221. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00396.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith GD, Gunthorpe MJ, Kelsell RE, Hayes PD, Reilly P, Facer P, Wright JE, Jerman JC, Walhin JP, Ooi L, Egerton J, Charles KJ, Smart D, Randall AD, Anand P, Davis JB. TRPV3 is a temperature-sensitive vanilloid receptor-like protein. Nature. 2002;418:86–190. doi: 10.1038/nature00894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng X, Jin J, Hu L, Shen D, Dong XP, Samie MA, Knoff J, Eisinger B, Liu ML, Huang SM, Caterina MJ, Dempsey P, Michael LE, Dlugosz AA, Andrews NC, Clapham DE, Xu H. TRP channel regulates EGFR signaling in hair morphogenesis and skin barrier formation. Cell. 2010;141:331–343. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandadi S, Sokabe T, Shibasaki K, Katanosaka K, Mizuno A, Moqrich A, Patapoutian A, Fukumi-Tominaga T, Mizumura K, Tominaga M. TRPV3 in keratinocytes transmits temperature information to sensory neurons via ATP. Pflugers Arch. 2009;458:1093–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moqrich A, Hwang SW, Earley TJ, Petrus MJ, Murray AN, Spencer KS, Andahazy M, Story GM, Patapoutian A. Impaired thermosensation in mice lacking TRPV3, a heat and camphor sensor in the skin. Science. 2005;307:1468–1472. doi: 10.1126/science.1108609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith GD, Gunthorpe MJ, Kelsell RE, Hayes PD, Reilly P, Facer P, Wright JE, Jerman JC, Walhin JP, Ooi L, Egerton J, Charles KJ, Smart D, Randall AD, Anand P, Davis JB. TRPV3 is a temperature-sensitive vanilloid receptor-like protein. Nature. 2002;418:186–190. doi: 10.1038/nature00894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu H, Ramsey IS, Kotecha SA, Moran MM, Chong JA, Lawson D, Ge P, Lilly J, Silos-Santiago I, Xie Y, DiStefano PS, Curtis R, Clapham DE. TRPV3 is a calcium-permeable temperature-sensitive cation channel. Nature. 2002;418:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature00882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng W, Yang F, Takanishi CL, Zheng J. Thermosensitive TRPV channel subunits coassemble into heteromeric channels with intermediate conductance and gating properties. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;129:191–207. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng W, Yang F, Liu S, Colton CK, Wang C, Cui Y, Cao X, Zhu MX, Sun C, Wang K, Zheng J. Heteromeric heat-sensitive transient receptor potential channels exhibit distinct temperature and chemical response. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:7279–7288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu H, Delling M, Jun JC, Clapham DE. Oregano, thyme and clove-derived flavors and skin sensitizers activate specific TRP channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:628–635. doi: 10.1038/nn1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner TF, Loch S, Lambert S, Straub I, Mannebach S, Mathar I, Dufer M, Lis A, Flockerzi V, Philipp SE, Oberwinkler J. Transient receptor potential M3 channels are ionotropic steroid receptors in pancreatic beta cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:1421–1430. doi: 10.1038/ncb1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vriens J, Owsianik G, Hofmann T, Philipp SE, Stab J, Chen X, Benoit M, Xue F, Janssens A, Kerselaers S, Oberwinkler J, Vennekens R, Gudermann T, Nilius B, Voets T. TRPM3 Is a Nociceptor Channel Involved in the Detection of Noxious Heat. Neuron. 2011;70:482–494. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thiel G, Muller I, Rossler OG. Signal transduction via TRPM3 channels in pancreatic beta-cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013;50:R75–R83. doi: 10.1530/JME-12-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dietrich MO, Horvath TL. Hypothalamic control of energy balance: insights into the role of synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeltser LM, Seeley RJ, Tschop MH. Synaptic plasticity in neuronal circuits regulating energy balance. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:1336–1342. doi: 10.1038/nn.3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Catterall WA, Leal K, Nanou E. Calcium channels and short-term synaptic plasticity. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:10742–10749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.411645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Appleyard SM, Bailey TW, Doyle MW, Jin Y-H, Smart JL, Low MJ, Andresen MC. Proopiomelanocortin neurons in nucleus tractus solitarius are activated by visceral afferents: Regulation by cholecystokinin and opioids. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:3578–3585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4177-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Browning KN, Wan S, Baptista V, Travagli RA. Vanilloid, purinergic, and CCK receptors activate glutamate release on single neurons of the nucleus tractus solitarius centralis. Am. J. Physiol Regul. Integr. Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R394–R401. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00054.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui RJ, Li X, Appleyard SM. Ghrelin inhibits visceral afferent activation of catecholamine neurons in the solitary tract nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:3484–3492. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3187-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wan S, Browning KN, Coleman FH, Sutton G, Zheng H, Butler A, Berthoud HR, Travagli RA. Presynaptic melanocortin-4 receptors on vagal afferent fibers modulate the excitability of rat nucleus tractus solitarius neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4957–4966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5398-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams KW, Smith BN. Rapid inhibition of neural excitability in the nucleus tractus solitarii by leptin: implications for ingestive behaviour. J. Physiol. 2006;573:395–412. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zsombok A, Bhaskaran MD, Gao H, Derbenev AV, Smith BN. Functional plasticity of central TRPV1 receptors in brainstem dorsal vagal complex circuits of streptozotocin-treated hyperglycemic mice. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:14024–14031. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2081-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]