Abstract

Background:

Uttarakhand state is a known endemic area for iodine deficiency.

Objective:

The present study was conducted with an objective to assess the iodine nutritional status amongst pregnant mothers (PMs) in districts: Pauri (P), Nainital (N) and Udham Singh Nagar (USN) of Uttarakhand state.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty clusters from each district were selected by utilizing the population proportionate to size cluster sampling methodology. A total of 1727 PMs from P (481), N (614) and USN (632) were included. The clinical examination of the thyroid of each PM was conducted. Urine and salt samples were collected from a sub samples of PMs enlisted for thyroid clinical examination.

Results:

The total Goiter rate was found to be 24.9 (P), 20.2 (N) and 16.1 (USN)%. The median urinary iodine concentration (UIC) levels were found to be 110 μg/L (P), 117.5 μg/L (N) and 124 μg/L (USN). The percentage of PMs consuming salt with iodine content of 15 ppm and more was found to be 57.9 (P), 67.0 (N) and 50.3 (USN).

Conclusion:

The findings of the present study revealed that the PMs in all three districts had low iodine nutritional status as revealed by UIC levels of less than 150 μg/L.

Keywords: Goiter, iodine deficiency disorder, pregnant mothers, salt iodisation, urinary iodine concentration

INTRODUCTION

Iodine is an essential micronutrient required for production of thyroid hormones. Iodine deficiency (ID) is the principal factor responsible for abnormal physical and mental development among children.[1] All age groups are affected by ID, but growing children and pregnant mothers (PMs) are the most vulnerable as they are sensitive to even marginal ID.[2] During pregnancy, the requirement of iodine increases to 250 μg/day when compared to normal adult (150 μg/day) to meet the higher metabolic demands of thyroxin (T4) production, transfer iodine to fetus and increased renal iodine clearance by the mother.[1] Inadequate consumption of iodine by the PM, leads to insufficient production of thyroxin by the fetus resulting in retarded fetal growth. ID increases the risk of still birth, abortions, increased perinatal deaths, infant mortality, and congenital anomalies.[3] Children born to iodine deficient PMs often results in stunted growth, cretinism and have lower intelligent quotient scores.[4]

World-wide, iodine deficiency disorders (IDD) is public health problem that needs utmost attention.[5] ID affects more than 2 billion people world-wide.[6] A recent study conducted in United Kingdom revealed that 67% of the PMs had low iodine intake.[7] It is estimated that in India, more than 200 million people are at the risk of ID, while 71 million suffer from goiter and other IDD.[5] The irrigated plains and the hilly regions of the sub-Himalayas is a known IDD endemic belt. Uttarakhand state is a known endemic region for ID. An earlier study conducted among adolescent PMs in Uttaranchal (2003) reported total Goiter rate (TGR) of 15% and median urinary iodine concentration (UIC) level of 95 μg/L indicating presence of ID.[8] Various studies conducted among PMs from different regions of India reported the prevalence of IDD as 22.9% (Delhi), and 9.5% (Himachal Pradesh), respectively.[2,9]

There are studies available on status of ID amongst school age children; however there is a lack of data on the prevalence of ID among PMs in Uttarakhand state. Thus, the present study was conducted to assess the iodine nutrition status among PMs in three districts (Pauri [P], Nainital [N], and Udham Singh Nagar [USN]) of Uttarakhand.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted in the year 2012 in state of Uttarakhand, which has 13 districts distributed in three geographical regions namely: Garhwal, Kumaon, and Tarai (plain), one district was selected randomly from each region, i.e., P, N and USN, respectively. In each district, 30 clusters were identified by utilizing population proportionate to size sampling methodology recommended by WHO/UNICEF/ICCIDD.[1] The antenatal clinics organized in 30 clusters were identified. In the identified antenatal clinics, PMs were selected from these clinics and were included in the study. The PMs consuming drugs, which could influence their thyroid status, were excluded from the study.

The clinical examination of thyroid of each PM was conducted by two trained field investigators. A minimum of 16 PMs were included from each cluster. The grading of goiter was done according to the criteria recommended jointly by WHO/UNICEF/ICCIDD (i) Grade 0 - not palpable and not visible (ii) Grade I - palpable but not visible (iii) Grade II - palpable and visible.[1] The sum of Grade I and II provided the TGR in the study population. When in doubt, all the investigators recorded the immediate lower grade. The intra and inter observer variation was controlled by repeated training and random examination of goiter grades by first author. The intra and inter observer variation was minimized by repeated training of two field investigators and by random examinations of Goiter grades by first author. The intra observer variation was 10% and inter observer variation was 30% at the beginning of study. This was minimized to less than 5% by repeated training before the data collection was started.

In each cluster, 13 casual urine samples were collected from the list of PMs enrolled for clinical thyroid examination. Plastic bottles with screw caps were provided to each PM for the urine samples. The samples were stored in the refrigerator until analysis. The analysis was done within 2 months. The UIC levels were analyzed using the wet digestion method.[10] A pooled urine sample was prepared for internal quality control (IQC) assessment. The IQC sample was analyzed 30 times and mean and standard deviation (SD) of this pooled was calculated. The IQC samples of known concentration of iodine content were run with every batch of study urine samples. If the results of the IQC samples were within the range (i.e., mean ± 2 SD) then the urine sample results of study subjects was deemed valid. However, if the results were outside the range of IQC sample, then the whole batch of the study subjects was repeated.

Similarly, a minimum of 11 PMs were selected from each cluster and were provided with an auto seal polythene pouches with an identification slip. They were requested to bring four teaspoons of salt (about 20 g) from their family kitchen and the iodine content of the salt samples was analyzed by standard iodometric titration method.[11] Since iodine crystals are smaller than salt crystals and hence they get settled at the bottom of the pack. Thus, PMs were instructed to mix the sample of salt properly before sampling.

The project was approved by Ethical Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi.

Sample size

Keeping in view the anticipated prevalence of 5%, a confidence level of 95%, absolute precision of 3% and a design effect of 2, a sample size of 450 was calculated. However, we included 481 (P), 614 (N) and 632 (USN) PMs from each district.

RESULT

Prevalence of Goiter

A total of 1727 PMs were selected from P (481), N (614) and USN (632).

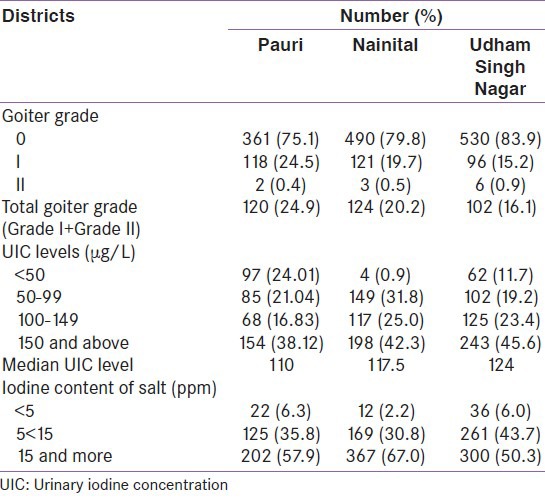

The prevalence of Goiter Grade I was found to be 24.5% (P), 19.7% (N) and 15.2% (USN). The prevalence of Goiter Grade II was found to be 0.4% (P), 0.5% (N) and 0.9% (USN). The TGR was found to be 24.9 (P), 20.0 (N) and 16.1 (USN)% [Table 1].

Table 1.

Distribution of pregnant mother in three districts (Pauri, Nainital, Udham Singh Nagar) of Uttarakhand

UIC

A total of 1404 urine samples were collected from P (404), N (468) and USN (532). The median UIC levels were found to be 110 μg/L (P), 117.5 μg/L (N) and 124 μg/L (USN), respectively. PMs in all the three districts had poor iodine nutrition status. The percentage of PMs having UIC level of <50 μg/L were 24.0 (P), 0.9 (N) and 11.7 (USN) [Table 1].

Iodine content of salt consumed in the families of PMs

A total of 1494 salt samples were collected from District Pauri (349), N (548) and USN (597). It was found that 57.9 (P), 67.0 (N) and 50.3 (USN)% of salt samples had iodine content of 15 ppm and more which is a stipulated level of iodine by Government of India [Table 1].

DISCUSSION

PMs are the most vulnerable to ID. Pregnant women are a prime target group for IDD control activities because they are especially sensitive to marginal ID. Inadequate iodine status during early pregnancy is adversely associated with child cognitive development. The thyroid hormones are crucial for brain and neurological development. The severe form of ID leads to cretinism and mental retardation. These outcomes are irreversible.[1]

A recent study among PMs in United Kingdom has documented that child of iodine deficient PMs are more likely to have low verbal Intelligent Quotient, poor reading accuracy, and comprehension.[7]

In the present study, the prevalence of Goiter was found to be 24.9% (P), 20.0% (N) and 16.1% (USN) indicating ID as a moderate public health problem among PM in Uttarakhand. The TGR illustrates past iodine status and decrease in iodine intake. Earlier studies conducted amongst PMs in Uttaranchal (2003) and Rajasthan (2008) revealed a Goiter prevalence of 15.0% and 3.1%, respectively.[8,3]

UIC is currently the most practical biochemical marker for iodine nutrition when carried out with appropriate technology and sampling. Assessing urinary iodine in PMs provides an opportunity to establish the iodine status of a group that is crucial because of the susceptibility of the developing fetus to ID.[1] During pregnancy, median UICs of between 150 μg/L and 250 μg/L define a population, which has no ID.[12] In the present study, the UIC levels of less than 150 μg/L were observed in all the three districts. The median UIC levels among PMs were found to be 110 μg/L (P), 117.5 μg/L (N) and 124 μg/L (USN), respectively indicating the presence of insufficient iodine intake by the PMs in all the three districts. An earlier study conducted among PMs in district USN reported the median UIC level of 95.0 μg/L.[8]

The findings of the present study were substantiated by low percentage of consumption of salt with adequate iodine content. It was observed that 57.9% (P), 67.0% (N) and 50.3% (USN) of families were consuming salt with iodine content of more than 15 ppm. An earlier study conducted in Rajasthan (2008) revealed that only 22.7% of PMs consumed salt with iodine content of 15 ppm and more.[3]

We are unable to compare findings of our study on iodine status amongst PMs with other similar studies due to lack of published data.

Findings of our study indicates that the PMs in all the three districts of Uttarakhand are iodine deficient as indicated by low median UIC levels and lower consumption of adequately iodized salt. Thus, there is a need for revitalizing the National IDD control program to ensure supply of salt with adequate iodine content of 15 ppm and more to achieve elimination of IDD in Uttarakhand state. Since, most vulnerable group for ID for health consequences is the fetus and hence the assessment of ID status of the PMs should be included in the monitoring of IDD control program.

Constraints of the study

The intra and inter observer variation in goiter examination was controlled by repeated training and random examination of goiter grade by expert. However in spite of all the precautions for the quality control, a possibility existed for misclassification of normal thyroid gland to goiter Grade I.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are extremely grateful to Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi for providing us the financial grant for conducting the study (vide letter No: 5/9/1025/201 1-RHN).

Footnotes

Source of Support: We are extremely grateful to Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi for providing us the financial grant for conducting the study (vide letter No: 5/9/1025/201 1-RHN)

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO/UNICEF/ICCIDD. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2007. Assessment of Iodine Deficiency Disorders and Monitoring their Elimination. A Guide for Programme Managers. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapil U. Goiter in India and its prevalence. J Med Sci Fam Plann. 1998;3:46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh MB, Fotedar R, Lakshminarayana J. Micronutrient deficiency status among women of desert areas of western Rajasthan, India. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:624–9. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grewal E, Khadgawat R, Gupta N, Desai A, Tandon N. Assessment of iodine nutrition in pregnant north Indian subjects in three trimesters. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:289–93. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.109716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiwari BK. New Delhi: Director General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2006. Revised Policy Guidelines on National Iodine Deficiency Disorders: IDD and Nutrition Cell. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Department of Nutrition for Health and Development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Iodine Status: Worldwide WHO Global Database on Iodine Deficiency Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bath SC, Steer CD, Golding J, Emmett P, Rayman MP. Effect of inadequate iodine status in UK pregnant women on cognitive outcomes in their children: Results from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) Lancet. 2013;382:331–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pathak P, Singh P, Kapil U, Raghuvanshi RS. Prevalence of iron, vitamin A, and iodine deficiencies amongst adolescent pregnant mothers. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:299–301. doi: 10.1007/BF02723584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapil U, Singh P. Current status of urinary iodine excretion levels in 116 districts of India. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50:245–7. doi: 10.1093/tropej/50.4.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunn JT, Crutchfield HE, Gutekunst R, Dunn D. Methods for Measuring Iodine in Urine: A Joint Publication of WHO/UNICEF/ICCIDD. 1993:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karmarkar MG, Pandav CS, Krishnamachari KA. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research, ICMR Press; 1986. Principle and Procedure for Iodine Estimation: A Laboratory Manual; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Secretariat. Andersson M, de Benoist B, Delange F, Zupan J. Prevention and control of iodine deficiency in pregnant and lactating women and in children less than 2-years-old: Conclusions and recommendations of the Technical Consultation. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:1606–11. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007361004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]