Abstract

Aims and objectives:

To study the frequency of thyroid, adrenal and gonadal dysfunction in newly diagnosed HIV-infected patients and to correlate them at different levels of CD4 cell counts.

Materials and Methods:

Forty-three HIV-positive cases were included in the study group. Cases were divided into three groups on the basis of CD4 cell count. Serum free T3, free T4, TSH, Cortisol, FSH, LH, testosterone and estradiol were estimated by the radioimmunoassay method. Hormone levels between cases were compared and their correlation with CD4 count was analyzed.

Results:

Prevalence of gonadal dysfunction (88.3%) was the most common endocrine dysfunction followed by thyroid (60.4%) and adrenal dysfunction (27.9%). Secondary hypogonadism (68.4%) was more common than primary (31.6%). Low T3 syndrome, that is, isolated low free T3, was the most common (25.6%) thyroid dysfunction followed by secondary hypothyroidism (16.2%) and subclinical hypothyroidism (11.6%). Adrenal excess (16.3%) was more common than adrenal insufficiency (11.6%). The difference in hormonal dysfunction between male and female was statistically insignificant (P > 0.05). 27.9% of patients had multiple hormone deficiency. There was negligible or no correlation between CD4 count and serum hormone level.

Conclusion:

In our study, endocrine dysfunction was quite common among HIV-infected patients but there was no correlation between hormone levels and CD4 count. Endocrine dysfunctions and role of hormone replacement therapy in HIV-infected patient needs to be substantiated by large longitudinal study, so that it will help to reduce morbidity, improve quality of life.

Keywords: Adrenal, endocrinopathy, gonad, human immunodeficiency virus, radioimmunoassay, thyroid

INTRODUCTION

Endocrine changes in the form of thyroid, adrenal, gonadal, bone, and metabolic dysfunction, have all been reported in both early and late stages of HIV infection.[1] There may be primary endocrine dysfunction as a result of direct effect of HIV as well as secondary endocrine dysfunction due to indirect effects of cytokines, opportunistic infections and rarely infiltration by a neoplasm. This may be manifested as subtle biochemical and hormonal changes to overt glandular failure. These endocrinopathies can have significant clinical impact, affecting growth and development, preservation of muscle mass, sexual function, fat distribution and quality of life in HIV-infected patients.[2] Wide accessibility of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) gave rise to increase life expectancy and hence high incidence of endocrinopathies in HIV-infected patients in the last two decades.[3] The paucity of data makes it difficult to make general recommendation about hormone replacement therapy in all HIV-infected patient with diminished circulating levels of a particular hormone to reduce morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected patients.[2]

To the best of our knowledge there were only few studies correlating endocrine dysfunction in HIV-infected patient with CD4 count, this pilot cross sectional study was undertaken to evaluate the frequency of thyroid, adrenal and gonadal dysfunction in newly diagnosed HIV-infected patients and to correlate them at different levels of CD4 cell counts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This observational cross-sectional study was conducted in Department of General Medicine and Department of Endocrinology, S.C.B. Medical College Cuttack from September 2012 to August 2013. The study group included 43 newly diagnosed HIV-positive patients admitted in medicine ward of S.C.B. Medical College, Cuttack. Patients with previous history of any endocrine disorders, taking drugs known to interfere with hormone metabolism or anti-retroviral therapy or hormone replacement therapy, having abnormal liver function or renal function tests, diabetics and alcoholics were excluded from the study group. HIV-positive patients were divided into three groups based on the CD4 cell counts. Group A: CD4 count <200/mm3, Group B: CD4 count 200-350/mm3 and Group C: CD4 count >350/mm3. Study was approved by the ethical committee of SCB Medical College, Cuttack. All patients gave written informed consent. HIV-positive status was confirmed by a series of three ELISA tests as per NACO guidelines [Comb AIDS, Retro check and Micro ELISA]. CD4 cells count was done by the Becton Dickinson FACS flow cytometer. For hormone assay blood was collected between 8 and 9 A.M. in fasting state. Serum was separated immediately and stored at −20°C. Serums free T3, free T4, TSH, 8 A.M serum cortisol, FSH, LH, testosterone, estradiol were estimated by the radioimmunoassay using PC-RIA. MAS.STARTEC (radioimmunoassay analyzer) Startec biomedical system AG, Birkenfeld. Normal reference range for the hormonal values was taken as cutoff from our laboratory reference range.

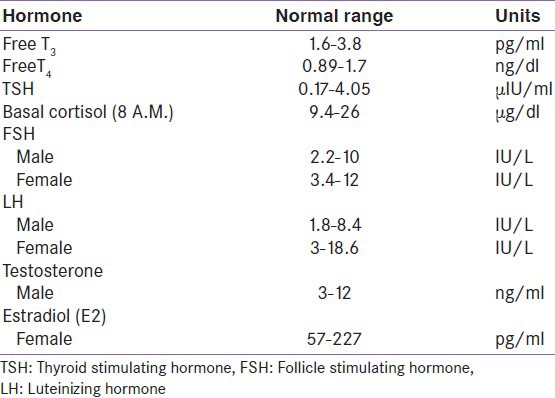

Definition: Various diagnosis was made as, primary hypogonadism: Low sex steroids with high gonadotrophin; secondary hypogonadism: Both sex steroids and gonadotrophin levels were low; isolated low T3: Low T3 with normal T4 and TSH; secondary hypothyroid: Low T3, Low T4, Normal or low TSH; subclinical hypothyroid: Normal T3 and T4 with TSH between 5 and 10 μIU/l; adrenal insufficiency: 8 A.M serum cortisol less than the lower reference cutoff value; adrenal excess: 8 A.M serum cortisol more than the lower reference cutoff value [Table 1].

Table 1.

Normal serum hormone levels

Statistical analysis

Calculations and analyses were done using the SPSS 19.0 software. Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Chi-square was used for comparison of proportions between two groups. Pearson's correlation coefficient analysis was used to determine associations between continuous data. The level of statistical significance was taken as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

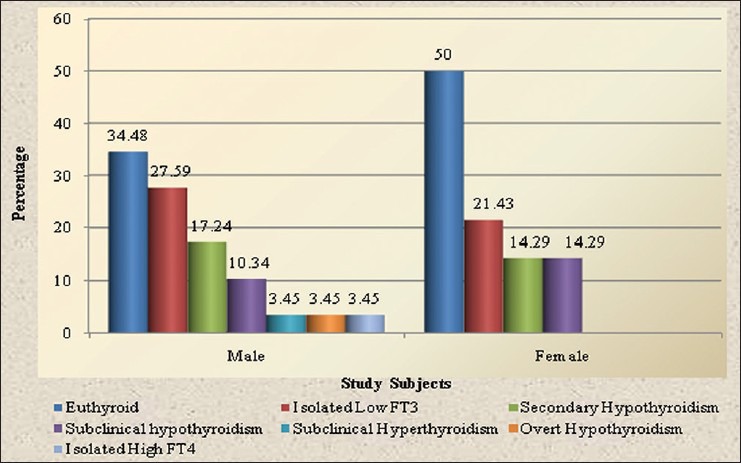

In this study out of 43 patients male outnumbered female with 29 (67.4%) and 14 (32.6%), respectively. The mean age and BMI (body mass index) of HIV-infected patients was 37.88 ± 7.8 year 17.84 ± 2.12 kg/m2, respectively. Most of the patients (55.8%) had CD4 cell count <200/mm3 with mean CD4 count 201.5 ± 159.9/mm3. Overall the prevalence of gonadal, thyroid and adrenal dysfunction were 88.3%, 60.4% and 27.9%, respectively. 27.9% of patients had multiple hormone deficiency. In gonadal dysfunction 89.7% males and 85.7% females had hypogonadism. Among male hypogonadism, 30.8% were primary and 69.2% were secondary. However, in female hypogonadism, 33.3% were primary and 66.7% were secondary. The prevalence of thyroid dysfunction among the HIV-infected patients in the decreasing order of frequency was isolated low free T3 (25.6%), secondary hypothyroidism (16.2%) and subclinical hypothyroidism (11.6%) with other thyroid dysfunction reported in our study was isolated high free T4, overt hypothyroidism and subclinical hyperthyroidism each of them accounting 3.45% of case group. Thyroid dysfunction was more common in males (65.5%) than females (50%) [Figure 1]. In adrenal dysfunction, 11.6% had adrenal insufficiency and 16.3% had adrenal excess. Adrenal insufficiency was more common in females (21.45%) than males (6.9%), whereas adrenal excess was more common in males (24.1%) than females. The difference in hormonal dysfunction between male and female was statistically insignificant (P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Types of thyroid dysfunction in HIV-infected patients

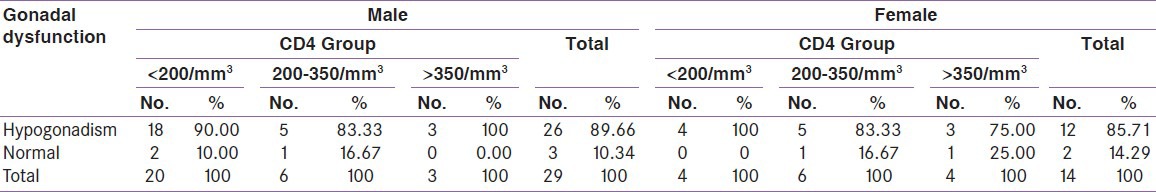

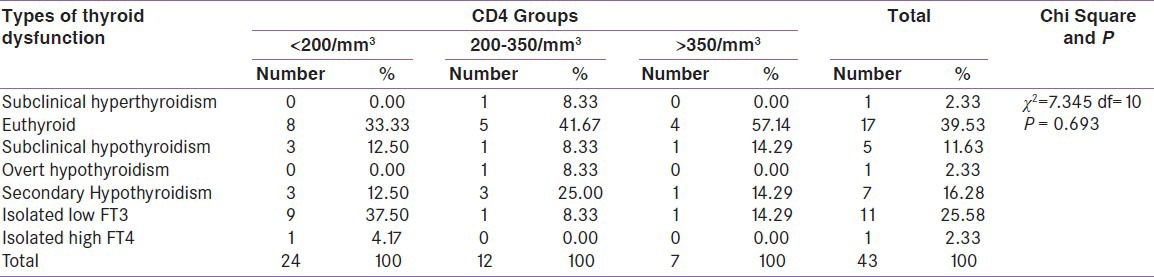

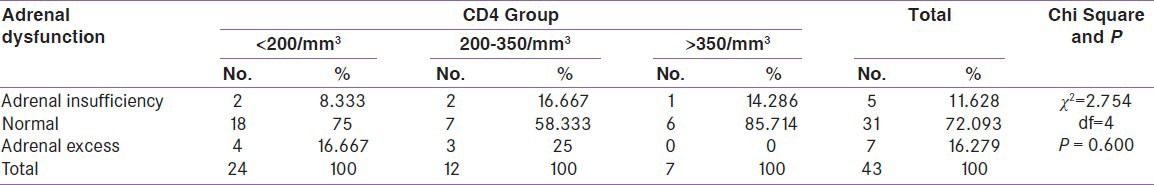

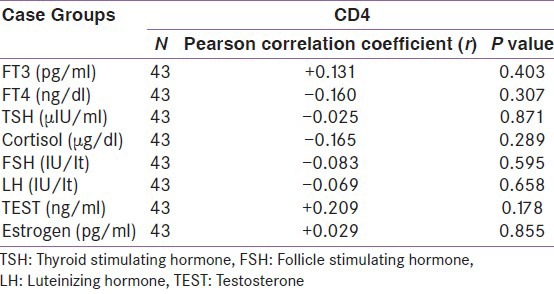

When compared between the HIV positive groups on the basis of CD4 count, male hypogonadism was 90% in group A, 83.3% in group B, 100% cases in group C and female hypogonadism was 100% in group A, 83.3% in group B, 75% in group C [Table 2]. The thyroid dysfunction was 66.7% in group A, 58.3% in group B and 42.9% in group C. Isolated low free T3 (low T3 syndrome) was found in 37.5% in group A, 8.33% in group B, 14.3% in group C [Table 3]. Adrenal insufficiency was 8.3% in group A, 16.7% in group B, 14.2% in group C and adrenal excess was 16.7% in group A, 25% in group B [Table 4]. Test of strength of linear dependence between CD4 count and various hormone levels was done using Pearson's correlation coefficient. For all the hormone the coefficient of correlation(r) was nearer to zero (r= +0.13, −0.16, −0.03, −0.16, −0.08, −0.07, + 0.21, +0.03 for free T3, free T4, TSH, cortisol, FSH, LH, testosterone and estradiol, respectively) and P value for each hormone >0.05 [Table 5]. This indicates that there was negligible or no correlation between CD4 count and serum hormone level.

Table 2.

Distribution of gonadal dysfunction among CD4 groups

Table 3.

Distribution of types of thyroid dysfunction among CD4 Groups

Table 4.

Distribution of adrenal dysfunction among CD4 groups

Table 5.

Correlations of hormone level with CD4 count

DISCUSSION

HIV infection and AIDS is a global pandemic, with cases reported from virtually every country. Globally, an estimated 35.3 (32.2–38.8) million people were living with HIV in 2012.[2] According to the HIV estimations 2012, the estimated number of people living with HIV/AIDS in India was 20.89 lakhs in 2011. But still, India is estimated to have the third highest number of people living with HIV/AIDS, after South Africa and Nigeria.[3]

Endocrine dysfunction is common in HIV-infected patients and in patients with AIDS and this dysfunction now came to attention because of the success of antiretroviral medication leads to patients lived longer.

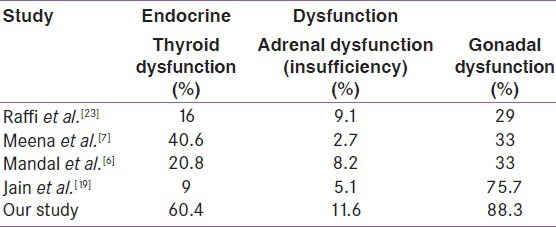

Hypogonadism was the most common endocrine dysfunction found in our study followed by thyroid and adrenal dysfunction [Table 6]. This was similar to the study by Katz et al. who reported that hypogonadism is probably the most common endocrinological abnormality in HIV-infected men.[4] According to Dobs et al. hypogonadism was found in 6%, 40% and 50% of asymptomatic HIV positive, symptomatic HIV positive and in AIDS patients, respectively.[5] Secondary hypogonadism was more common than primary hypogonadism in our study correlating with the finding of Mandal SK et al. but in Meena LP et al. primary hypogonadism was more common cause of hypogonadism.[6,7] In our study the cause of secondary hypogonadism was might be a decrease in gonadotropin secretion during acute or chronic severe illness and involvement of hypothalamic or pituitary tissue by opportunistic infections or malignancies in both sexes.[1,8] Primary gonadal failure may be due to opportunistic infections (e.g. Cytomegalo virus, Mycobacterium avium complex, Cryptococcus neoformans, etc) infiltration by a neoplasm like Kaposi's sarcoma, IL1 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) that decrease leydig cell steroidogenesis.[9,10]

Table 6.

Comparison of prevalence of endocrine dysfunction in previous studies

Isolated low Free T3 was the most common thyroid dysfunction in our study found in both male and female cases. This was similar to the findings reported by Merenich et al.,[11] Madge et al., and Hoffman et al. who also observed that non-thyroidal illness was most common thyroid dysfunction in HIV-infected patients.[12,13] Low T 3 syndrome in severe illness may be due to release of cytokines such as IL-6, and impaired deiodination from T4 to T3.[14] Secondary hypothyroidism in our study might be due to the stress of the illness as found in 6% of cases in Ketsamathi et al.[15] In the present study the prevalence of sub-clinical hypothyroidism was 11.6% and higher in female as compared to male patients. The reported prevalence by other authors were 17.6% by Brockmeyer et al.,[16] 6.6% by Beltran et al.,[17] 6% by Ketsamathi et al.,[15] 4% by Madge et al.,[12] 10.6% by Bongiovani et al.,[18] 30% by Meena et al.,[7] and 7% by Jain et al.[19] Prevalence of overt hypothyroidism in the current study was 3.45%. This was also similar to the observation made by other authors like 2.6% by Beltran et al.,[17] 1.5% by Ketsamathi et al.,[15] 2.5% by Madge et al.,[12] 10.66% by Meena et al.,[7] and 2% by Jain et al.,[19] and it may be due to increased risk of opportunistic infection which is an independent risk factor for decrease thyroid function.[9] Isolated high free T 4 levels were seen in 3.45% of cases in the present study. This finding was again similar to other studies by Beltran et al. and Jain et al.[20,21] The present study had 3.45% sub-clinical hyperthyroidism. It was less than 1% in a study by Madge et al. and Ketsamathi reporting it to be at 0.5%.[12,15]

In our study 11.6% had adrenal insufficiency and 16.3% had adrenal excess. According to study by Meena et al.,[7] 2.66% had adrenal insufficiency and 26% had adrenal excess; and by Jain et al.,[19] 5.1% had adrenal insufficiency and 39.1% had adrenal excess. Mandal et al.[6] reported low serum cortisol in 8.3% cases. The elevated cortisol level may be to the stress of HIV infection as well as associated opportunistic infection, which the patient was suffering from. Adrenal insufficiency may be due to tuberculosis of adrenal gland which is very common in India.

When compared between the HIV-positive groups on the basis of CD4 count, the thyroid dysfunction and hypogonadism were negatively correlated with CD4 count as found by Meena et al.[7] Isolated low free T3 (low T3 syndrome) was profound in group A CD4 count group but adrenal insufficiency was noted more prevalent in group B CD4 count group.

In this study by using Pearson's correlation coefficient we found negligible or no correlation between CD4 count and serum thyroid level which was similar to the findings of Mandal et al. (TSH, free T3, and free T4 achieved a poor correlation when matched with CD4 counts (r = 0.14, 0.15, 0.15 respectively; P value in each case > 0.05)) but contradicts Jain et al. where they found a direct correlation between CD4 count and Free T3 and Free T4 values (r = 0.357 with P < 0.05; r = 0.650 with P < 0.05, respectively) and there was an inverse correlation of CD4 counts with serum TSH levels (r = −0.470 with P < 0.050).[6,21]

In our study the correlation coefficient between serum cortisol and CD4 count was negligible as observed by Mandal et al. and Odeniyi et al. but Jain et al. in 2011 found a significant correlation coefficient between serum cortisol and CD4 count (r = −0.301 with P < 0.0001).[6,7,22]

In our study, there was negligible or no correlation of CD4 count with gonadotropin, serum testosterone and estradiol but according to Mandal et al. the gonadotropin and total testosterone ere all found to be decreased proportionately with the CD4 count (r = 0.43; P = 0.07, r = 0.51; P = 0.32 r = 0.39; P = 0.03, respectively).[6]

Limitation

In our study, only the prevalence of endocrine dysfunction was estimated. No attempt was made to evaluate the cause of endocrinopathy. Dyanamic testing was not done to look for adrenal axis and less number of patients found to conclude for adrenal disorders.

CONCLUSION

In our study, endocrine dysfunction was common among HIV-infected patients. Gonadal dysfunction was the most common endocrine dysfunction followed by thyroid and adrenal dysfunction. Secondary hypogonadism was more common than primary. Low T3 syndrome (isolated low free T3) was the most common thyroid dysfunction. Adrenal excess was more common than adrenal insufficiency. There was no significant difference in endocrine dysfunction between HIV-infected males and females. There was negligible or no correlation between CD4 count and serum hormone level.

However, it could be a chance finding due to small sample size, and Endocrine dysfunctions and role of hormone replacement therapy in HIV-infected patient needs to be substantiated by a large longitudinal study, so that it will help to reduce morbidity and improve quality of life.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grinspoon SK. Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM. William textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011. Endocrinology of HIV and AIDS; pp. 1675–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhasin S, Singh AB, Javanbakht M. Neuroendocrine abnormalities associated with HIV infection. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2007;30:749–64. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha U, Sengupta N, Mukhopadhyay P, Roy KS. Human immunodeficiency virus endocrinopathy. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15:251–60. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.85574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz MH, Zolopa AR. HIV Infection and AIDS. In: Mcphee S, Papadakis M, editors. Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment. 48th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2009. pp. 1176–205. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobs AS, Dempsey MA, Ladenson PW, Polk BF. Endocrine disorders in men infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Med. 1998;84:611–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandal SK, Paul R, Bandyopadhyay D, Basu AK, Mandal L. Study on endocrine profile of HIV infected male patients. Int Res J Pharm. 2013;4:220–3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meena LP, Rai M, Singh SK, Chakravarty J, Singh A, Goel R, et al. Endocrine changes in male HIV patients. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:365–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mylonakis E, Koutkia P, Grinspoon S. Diagnosis and treatment of androgen deficiency in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men and women. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:857–64. doi: 10.1086/322695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welch K, Finkbeiner W, Alpers CE, Blumenfeld W, Davis RL, Smuckler EA, et al. Autopsy findings in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. JAMA. 1984;252:1152–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Paepe ME, Waxman M. Testicular atrophy in AIDS: A study of 57 autopsy cases. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:210–4. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merenich JA, Mcdermott MT, Asp AA, Harrison SM, Kidd GS. Evidence of endocrine involvement early in the course of human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;70:566–71. doi: 10.1210/jcem-70-3-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madge S, Smith CJ, Lampe FC, Thomas M, Johnson MA, Youle M, et al. No association between HIV diseases and its treatment and thyroid function. HIV Med. 2007;8:22–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann CJ, Brown TT. Thyroid function abnormalities in HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:488–94. doi: 10.1086/519978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fauci AS, Lane HC. Human immunodeficiency virus disease: AIDS and Related disorders. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Publications; 2010. pp. 1506–68. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ketsamathi C, Jongjaroenprasert W, Chailurkit LO, Udomsubpayakul U, Kiertiburanakul S. Prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in Thai HIV-infected patients. Curr HIV Res. 2006;4:463–7. doi: 10.2174/157016206778560036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brockmeyer NH, Kreuter A, Bader A, Seemann U, Reimann G. Prevalence of endocrine dysfunction in HIV-infected men. Horm Res. 2000;54:294–5. doi: 10.1159/000053274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beltran S, Lescure FX, Desailloud R, Douadi Y, Smail A, Esper EI, et al. Increased prevalence of hypothyroidism among human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: A need for screening. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:579–83. doi: 10.1086/376626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bongiovanni M, Adorni F, Casana M, Tordato F, Tincati C, Cicconi P, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism in HIV-infected subjects. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:1086–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain N, Mittal M, Dandu H, Verma SP, Gutch M, Tripathi AK. An observational study of endocrine disorders in HIV infected patients from north India. J HIV Hum Reprod. 2013;1:20–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beltran S, Lescure FX, El Esper I, Schmit JL, Desailloud R. Subclinical hypothyroidism in HIV-infected patients is not an autoimmune disease. Horm Res. 2006;66:21–6. doi: 10.1159/000093228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain G, Devpura G, Gupta BS. Abnormalities in the thyroid function tests as surrogate marker of advancing HIV infection in infected adults. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009;57:508–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Odeniyi IA, Fasanmade OA, Ajala MO, Ohwovoriole AE. CD4 count as a predictor of adrenocortical insufficiency in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection: How useful? Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:1012–7. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.122615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raffi F, Brisseau JM, Planchon B, Rémi JP, Barrier JH, Grolleau JY. Endocrine function in 98 HIV-infected patients: A prospective study. AIDS. 1991;5:729–33. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199106000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]