Summary

Background

Social anxiety disorder—a chronic and naturally unremitting disease that causes substantial impairment—can be treated with pharmacological, psychological, and self-help interventions. We aimed to compare these interventions and to identify which are most effective for the acute treatment of social anxiety disorder in adults.

Methods

We did a systematic review and network meta-analysis of interventions for adults with social anxiety disorder, identified from published and unpublished sources between 1988 and Sept 13, 2013. We analysed interventions by class and individually. Outcomes were validated measures of social anxiety, reported as standardised mean differences (SMDs) compared with a waitlist reference. This study is registered with PROSPERO, number CRD42012003146.

Findings

We included 101 trials (13 164 participants) of 41 interventions or control conditions (17 classes) in the analyses. Classes of pharmacological interventions that had greater effects on outcomes compared with waitlist were monoamine oxidase inhibitors (SMD −1·01, 95% credible interval [CrI] −1·56 to −0·45), benzodiazepines (−0·96, −1·56 to −0·36), selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs and SNRIs; −0·91, −1·23 to −0·60), and anticonvulsants (−0·81, −1·36 to −0·28). Compared with waitlist, efficacious classes of psychological interventions were individual cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT; SMD −1·19, 95% CrI −1·56 to −0·81), group CBT (−0·92, −1·33 to −0·51), exposure and social skills (−0·86, −1·42 to −0·29), self-help with support (−0·86, −1·36 to −0·36), self-help without support (−0·75, −1·25 to −0·26), and psychodynamic psychotherapy (−0·62, −0·93 to −0·31). Individual CBT compared with psychological placebo (SMD −0·56, 95% CrI −1·00 to −0·11), and SSRIs and SNRIs compared with pill placebo (−0·44, −0·67 to −0·22) were the only classes of interventions that had greater effects on outcomes than appropriate placebo. Individual CBT also had a greater effect than psychodynamic psychotherapy (SMD −0·56, 95% CrI −1·03 to −0·11) and interpersonal psychotherapy, mindfulness, and supportive therapy (−0·82, −1·41 to −0·24).

Interpretation

Individual CBT (which other studies have shown to have a lower risk of side-effects than pharmacotherapy) is associated with large effect sizes. Thus, it should be regarded as the best intervention for the initial treatment of social anxiety disorder. For individuals who decline psychological intervention, SSRIs show the most consistent evidence of benefit.

Funding

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder, or social phobia, affects 7% of the population1 and follows a chronic and debilitating course if untreated.2 Findings from meta-analyses suggest that the disorder responds well to pharmacological,3 psychological,4 and self-help interventions,5 but most reviews have been limited to pairwise comparisons of subsets of these interventions.

Network meta-analysis has the advantage that all interventions that have been tested in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) can be simultaneously compared and their effects can be estimated relative to each other and to a common reference condition (eg, waitlist). Estimates of the effects of pairs of treatments that have often, rarely, or never been directly compared in a RCT can be calculated. As a consequence, network meta-analysis overcomes some of the limitations of traditional meta-analysis, in which conclusions are largely restricted to comparisons between treatments that have been directly compared in RCTs.

We undertook a network meta-analysis of all psychological and pharmacological interventions that are used in routine clinical practice for the initial treatment of social anxiety disorder and have been tested in RCTs.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We did a systematic review of interventions for social anxiety disorder according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.6 We searched the following databases between 1988 and Sept 13, 2013, with no language limits set, for published and unpublished studies on treatment of adults with social anxiety disorder: Australian Education Index, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, Applied Social Services Index and Abstracts, British Education Index, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CENTRAL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Database of Abstracts of Reviews and Effectiveness, Embase, Education Resources in Curriculum, Health Management Information Consortium, Health Technology Assessment, International Bibliography of Social Science, Medline, PreMEDLINE, PsycBOOKS, PsycEXTRA, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, and Social Sciencies Citation Index (appendix A). We also searched trial registries and reference lists of reviews and included studies. We consulted a group of experts from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guideline Development Group to identify relevant studies. We also wrote to authors of included studies to request trial registration details and unpublished outcomes and data; we also asked them to identify other potentially relevant studies.

All citations were screened by one author (KK or EM-W) who excluded citations that were not related to trials or to social anxiety disorder; potentially relevant citations were checked independently by a second author (EM-W or KK). Study characteristics, outcomes, and risk of bias7 were extracted by one author (KK or EM-W) and checked independently by a second (EM-W or KK).

Randomised clinical trials of interventions for adults aged at least 18 years who fulfilled diagnostic criteria for social anxiety disorder were included. Studies that primarily focused on the treatment of comorbid disorders (eg, substance abuse) were excluded, but participants in the included studies often met criteria for another disorder (eg, depression) and were included. Eligible interventions were oral drugs (fixed or flexible doses), psychological or behavioural interventions (eg, promotion of exercise; panel), and combinations of interventions. Pharmacological interventions did not need to be licensed for social anxiety disorder, but interventions not used routinely in the treatment of social anxiety disorder, according to the consensus of the investigators and the NICE Guideline Development Group for the guideline Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment and treatment, were excluded (ie, exposure with a cognitive enhancer, surgical interventions, injected drugs, and antipsychotics). Studies of computerised cognitive bias modification were analysed in a separate review (unpublished). We excluded drugs that are no longer marketed (eg, brofaromine) if trials compared them only with placebo because these trials would not provide information about eligible interventions.

Panel. Definition of psychological interventions.

Promotion of exercise

Behavioural change programmes that promote increased physical activity.

Exposure and social skills

Behavioural interventions that involve systematic exposure to social interactions or public speaking, but that do not include explicit cognitive techniques.

Group CBT

Therapist-led, group-based interventions that use both behavioural strategies (eg, exposure) and various cognitive strategies (eg, cognitive restructuring, video feedback, and attention training). Specific CBT manuals were followed for this intervention or the study investigators described the intervention as CBT.

Individual CBT

Individual interventions for which specific CBT manuals were followed or that were described as CBT by study investigators.

Other psychological therapy

Psychological therapies not included elsewhere were grouped to improve estimates of variance for the class model. This class includes the specific effects of interpersonal psychotherapy, mindfulness training, and supportive therapy.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy

Short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy, for which a treatment manual specifically for social anxiety disorder can be followed.

Psychological placebo

A psychological intervention that includes features common to most well-undertaken psychological therapies (ie, non-specific components of treatment) and that was designed as a credible intervention.

Self-help with support

Interventions (usually CBT based) that are delivered by book or computer with limited therapist support (eg, short meetings, email support, or phone calls). For the purpose of clinical trials, participants typically received clinical interviews at the beginning and end of treatment.

Self-help without support

Interventions (usually CBT based) that are delivered exclusively by book or computer. For the purpose of clinical trials, participants were interviewed at the beginning and end of treatment.

CBT=cognitive–behavioural therapy.

We limited the network meta-analysis to interventions that people with social anxiety disorder and clinicians might regard as first-line treatments because network analysis assumes that treatment effects are transferable across studies. Ideally, all trial populations included in the network meta-analysis could have been eligible for all the treatment options investigated. Clinically, people choosing a first-line intervention have a different set of treatment options compared with people choosing second-line interventions; there would be a high risk that the assumption of exchangeability would be violated by the inclusion of clinically heterogeneous populations (eg, people who had not responded to treatments assessed in other studies). We identified eligible interventions by reviewing published and unpublished studies and through consultation with clinicians and experts (including people with social anxiety disorder, pharmacists, psychologists, and psychiatrists). We included interventions rather than excluded them if some experts thought they could be used as a first-line treatment.

Statistical analysis

If a study reported continuous results for participants who completed the study only, as well as continuous results that accounted for missing data (eg, effects calculated using multiple imputation), we extracted the data that accounted for missing data. Studies reported several measures of social anxiety, none of which were common to all trials, so we calculated treatment effects for each study as a standardised mean difference (SMD). To reduce measurement error, we calculated the mean effect (Hedges' g) of all eligible scales for studies that reported more than one measure, taking between-scale correlation into account.8 For trials that reported only the change from baseline, the SD at baseline was used to ensure standardising constants were comparable across trials. Based on published psychometric properties and data from clinically referred participants who completed several measures (appendix A), we assumed that measures were equally responsive and had a mean correlation of 0·65.

Where reported, we also extracted data for recovery from social anxiety disorder (ie, no longer meeting criteria for the diagnosis) assuming that study dropouts had not recovered. We used the relation between continuous outcomes and recovery to estimate the treatment effect for all studies, including those that did not report recovery (appendix A).

We did a Bayesian random-effects network meta-analysis,9 which accounts for the correlation between trial-specific effects and random effects of trials with more than two arms.10 We analysed interventions by class (eg, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs and SNRIs]) and individually (eg, sertraline). In general, treatments with similar mechanisms of action were grouped in classes in which pooled effects were assumed to be similar. This grouping had the effect of drawing individual treatment effects towards the class mean. We used non-informative priors, except for the prior for within-class variability. Because there were few data to reliably estimate within-class variation, this prior was informative and was restricted with an inverse-gamma prior. This restriction limited variability to a clinically plausible range and had the effect of restricting the effect of outliers within a class; specific interventions with inconsistent results based on limited data would have otherwise had an undue effect on the results. For treatments not belonging to a class, we assumed no class variability and estimated only between-study heterogeneity. Combination interventions were included in a class because analysing of each combination as a distinct class would underestimate true variance (appendix A).

We estimated the effect for each class and for each individual intervention using Markov chain Monte Carlo implemented in WinBUGS version 1.4.3.11 The first 20 000 iterations were discarded, and 50 000 further iterations were run. Two chains with different initial values were run simultaneously to assess convergence using the Gelman–Rubin diagnostic trace plots. We estimated effects with and without the consistency assumptions for individual treatment effects (ie, without grouping by class) and compared the residual deviance of each to assess consistency.12 We compared the fit of the standard model to the class model by comparing the residual deviance, and we chose the model with the lowest deviance information criterion.9 We used treatment effects to estimate change on continuous measures and the absolute rate of recovery for each intervention with 95% credible intervals (CrIs). Main effects are reported compared with waitlist, which was chosen as the reference treatment a priori.

All outcomes and study effects used in the analysis are available online (appendix B).

This study is registered with PROSPERO, number CRD42012003146.

Role of the funding source

NICE commissioned the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) to develop guidance for the identification and management of social anxiety disorder. NICE also approved funding for the Technical Support Unit to support NCCMH in undertaking a network meta-analysis of intervention studies.

The funder of the study had no further role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

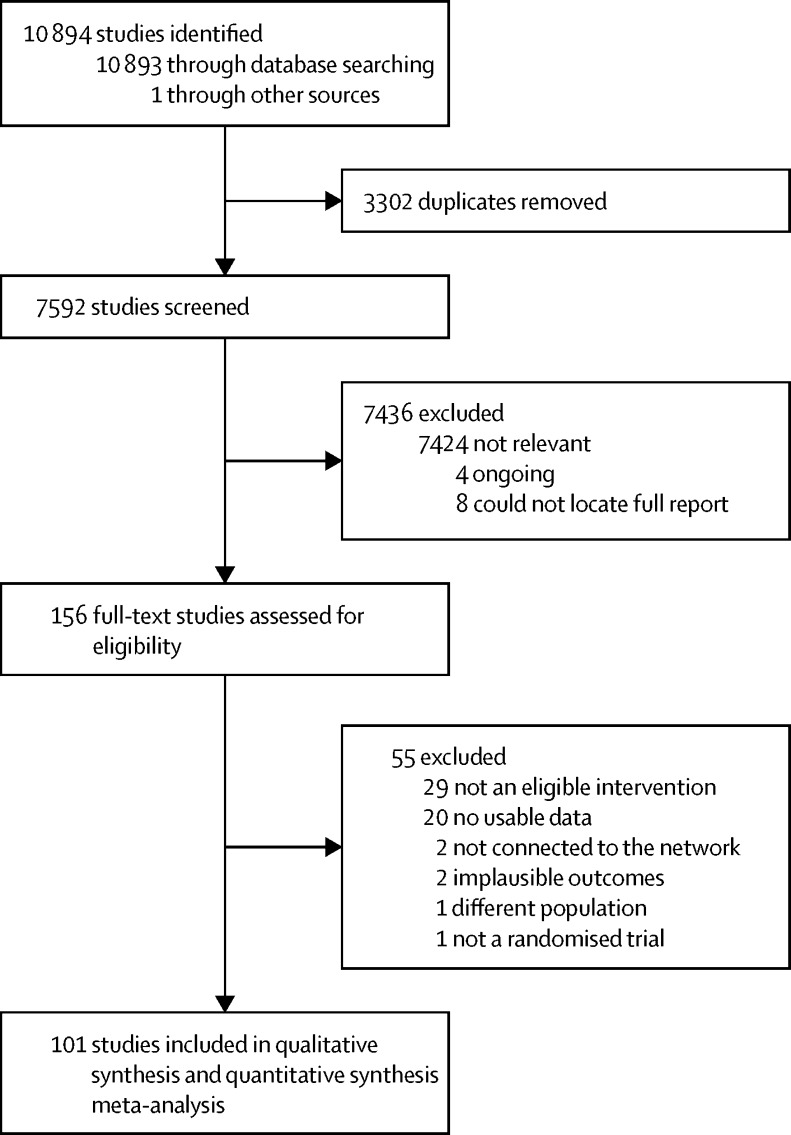

Between 1988 and Sept 13, 2013, we identified 168 potentially eligible studies, 12 of which were excluded: four were ongoing studies and for eight studies we could not identify a complete study report. We assessed 156 studies for eligibility (figure 1). 55 studies were excluded (appendix A) because they did not include an eligible intervention (n=29), reported no usable data (n=20), included no intervention already in the analysis and thus were not connected to this network (n=2), reported implausible outcomes (n=2), included a different population (n=1), or were not a randomised trial (n=1). 101 studies were included in the network analysis (appendix A).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart

PRISMA=Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses.

14 229 participants were randomly assigned in the trials, and 13 164 were included in the analysis because some trials did not report outcomes for all participants. There were 18–839 participants per study. Trials assessed 41 interventions or control conditions, which were grouped into 17 classes. Most trials included two groups (n=64), but some included three (n=28), four (n=7), or five groups (n=2). The median and mean duration of treatment was 12 weeks (range 2–28 weeks). Few studies provided controlled results for long-term follow-up, and so long-term follow-up data were not included in our analyses.

Participants had severe and longstanding social anxiety; of 65 studies reporting baseline Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale13 scores, the median of means was 78 (appendix A). The median of means age was 36 years and the median of percentages of participants who were white was 80%. About half of the included participants were women (52% median of means). Most psychological studies did not exclude participants receiving drug treatment, but trials of psychological interventions generally required participants to be on a stable dose of drug treatment for several months before random allocation. Participants were not receiving drug treatment in 44 trials. In 27 trials, 27% of participants (median of means) were receiving drug treatment at randomisation. The demographic characteristics of participants were similar across comparisons (appendix A), and there were no obvious differences in the initial severity of social anxiety symptoms; variation in severity was limited because studies had similar inclusion criteria.

We assessed all included trials for risk of bias (appendix A). Sequence generation and allocation concealment were adequately described in 74 and 69 trials, respectively (appendix A). Trials of psychological interventions were regarded as at high risk of bias for participant and provider masking per se, although treatment effects and side-effects could also make maintenance of masking difficult in pharmacological trials. Most reported outcomes were self-rated, and assessors were aware of treatment assignment in five trials. For incomplete outcome data, 26 trials were at high risk of bias (eg, those that reported only completer analyses and those with lots of missing data), and how missing data were handled was unclear in four trials.

Most included trials were not registered; only 37 trials were at low risk of selective outcome reporting bias (appendix A). In addition to risk of selective outcome reporting for included studies, there is risk of reporting bias because we could not locate a full report for eight studies, 20 studies reported no usable data, and two studies reported implausible outcomes. Results can be overestimated as a result of publication bias, particularly for interventions developed before mandatory trial registration. Unpublished information was obtained from trial investigators for 34 studies, including unpublished outcomes for 22 trials.

Excluding masking of participants and providers, which was impossible in studies of psychological interventions and difficult to maintain in studies of pharmacological interventions, only 28 trials were at low risk of bias for all other domains assessed by the Cochrane risk of bias assessment (appendix A).

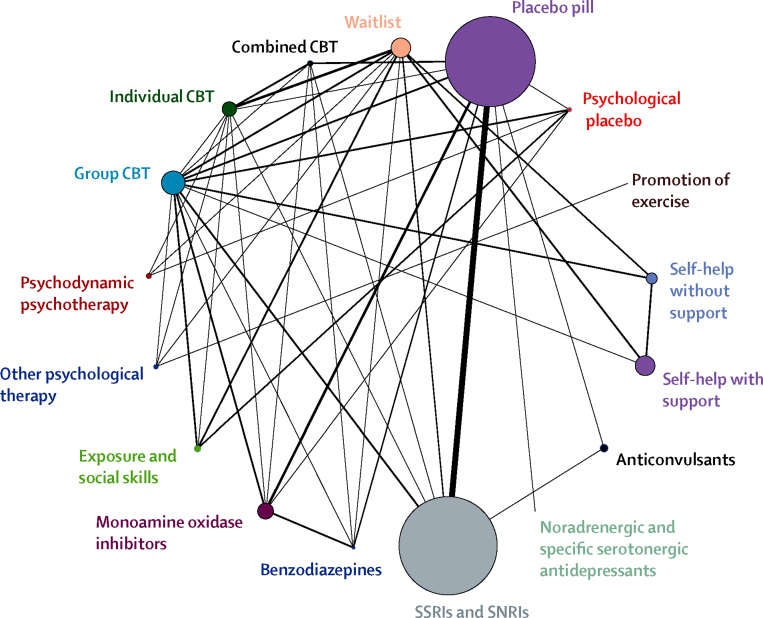

Figure 2 shows the network of comparisons among classes. Of 820 possible comparisons among 41 intervention or control conditions, 84 were studied directly (appendix A). 76 studies compared interventions with a control group; most drugs were compared with placebo, and most psychological interventions were compared with waitlist or with psychological placebo. The network also included 58 studies that compared active interventions, including four studies that compared psychological with pharmacological interventions.

Figure 2.

Network diagram representing direct comparisons among classes

The width of lines represents the number of trials in which each direct comparison is made. The size of each circle represents the number of people who received each treatment. CBT=cognitive–behavioural therapy. SNRI=serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. SSRI=selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor.

25 trials also reported recovery (appendix A), and we compared effects for continuous measures and loss of diagnosis for these studies, which suggested that continuous values provide lower treatment effects compared with odds ratios of recovery.

There was potential for inconsistency in nine of the 44 loops in the network—others were formed by multi-arm trials that are consistent by definition. There were no substantial differences in magnitude and direction between the results of the network meta-analysis and the results of pairwise comparisons. The posterior mean of the residual deviance was 165·3 in the standard network meta-analysis model compared with 176·3 in the independent-effect model that compares favourably with the number of treatment groups (n=148), suggesting the network better estimates treatment effects than pairwise analyses alone with no evidence of inconsistency.9

The random-effects class model was a good fit to the data compared with the individual-effects model (deviance information criterion 364·8 vs 371·0; lower values suggest a better fit), although the between-trials SD for heterogeneity had a posterior median of 0·19 (95% CrI 0·14–0·25). That is, there was some variability between classes that might be attributable to differences among the individual treatments beyond the within-class variability. For classes with few members, there was little information about within-class variability and the prior for within-class variability led to increased uncertainty in the estimated class effects.

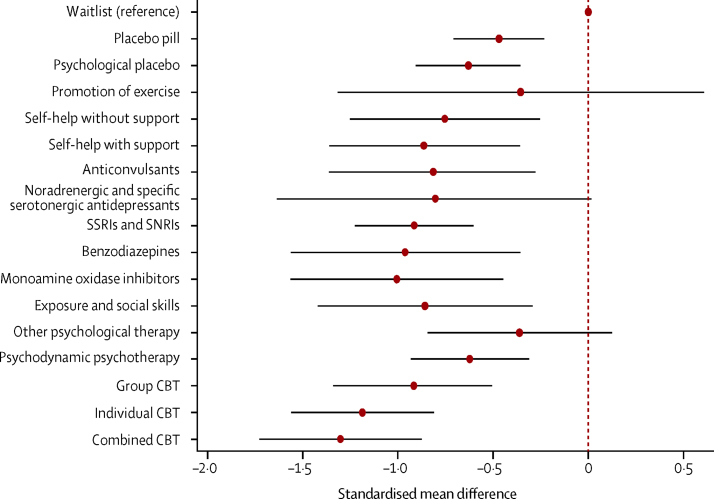

All pharmacological interventions apart from noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants had greater effects on outcomes compared with waitlist (table; figure 3). Mirtazapine, a noradrenergic and sepcific serotonergic antidepressant, was the only pharmacological intervention in a class by itself; its effect was not greater than that for waitlist (class effect SMD −0·80, 95% CrI −1·64 to 0·01), but only 30 people received the intervention. The largest effects were for MAOIs (class effect SMD −1·01, 95% CrI −1·56 to −0·45) and benzodiazepines (−0·96, −1·56 to −0·36), but the evidence for these effects was limited compared with evidence for SSRIs and SNRIs (−0·91, −1·23 to −0·60); more people received SSRIs and SNRIs (n=4043) than all other pharmacological interventions (n=999) or all psychological interventions (n=3312).

Table.

Summary of treatment effects compared with waitlist

| Trials | Participants | Class effect SMD (95% CrI) | Individual effect SMD (95% CrI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | |||||

| Waitlist | 28 | 802 | Reference | Reference | |

| Placebo pill | 42 | 3623 | −0·47 (−0·71 to −0·23) | .. | |

| Psychological placebo | 6 | 145 | −0·63 (−0·90 to −0·36) | .. | |

| Pharmacological interventions | |||||

| Anticonvulsants | 5 | 242 | −0·81 (−1·36 to −0·28) | .. | |

| Gabapentin | 1 | 34 | .. | −0·89 (−1·42 to −0·37) | |

| Levetiracetam | 1 | 9 | .. | −0·83 (−1·50 to −0·18) | |

| Pregabalin | 3 | 199 | .. | −0·72 (−1·07 to −0·37) | |

| Benzodiazepines | 5 | 112 | −0·96 (−1·56 to −0·36) | .. | |

| Alprazolam | 1 | 12 | .. | −0·85 (−1·40 to −0·30) | |

| Clonazepam | 4 | 100 | .. | −1·07 (−1·44 to −0·70) | |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors | 11 | 615 | −1·01 (−1·56 to −0·45) | .. | |

| Moclobemide | 6 | 490 | .. | −0·74 (−1·03 to −0·44) | |

| Phenelzine | 5 | 125 | .. | −1·28 (−1·57 to −0·98) | |

| Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (mirtazapine) | 1 | 30 | −0·80 (−1·64 to 0·01) | −0·81 (−1·45 to −0·16) | |

| SSRIs and SNRIs | 32 | 4043 | −0·91 (−1·23 to −0·60) | .. | |

| Citalopram | 2 | 18 | .. | −0·83 (−1·28 to −0·39) | |

| Escitalopram | 2 | 675 | .. | −0·88 (−1·20 to −0·56) | |

| Fluoxetine | 3 | 107 | .. | −0·87 (−1·16 to −0·57) | |

| Fluvoxamine | 5 | 500 | .. | −0·94 (−1·25 to −0·63) | |

| Paroxetine | 12 | 1449 | .. | −0·99 (−1·26 to −0·73) | |

| Sertraline | 3 | 535 | .. | −0·92 (−1·23 to −0·61) | |

| Venlafaxine | 5 | 759 | .. | −0·96 (−1·25 to −0·67) | |

| Psychological and behavioural interventions | |||||

| Exercise promotion | 1 | 18 | −0·36 (−1·32 to 0·61) | −0·36 (−1·07 to 0·36) | |

| Exposure and social skills | 10 | 227 | −0·86 (−1·42 to −0·29) | .. | |

| Exposure in vivo | 9 | 199 | .. | −0·83 (−1·07 to −0·59) | |

| Social skills training | 1 | 28 | .. | −0·88 (−1·38 to −0·38) | |

| Group CBT | 28 | 984 | −0·92 (−1·33 to −0·51) | .. | |

| Heimberg model | 11 | 338 | .. | −0·80 (−1·02 to −0·58) | |

| Other (no model specified) | 16 | 583 | .. | −0·85 (−1·04 to −0·68) | |

| Enhanced CBT | 1 | 63 | .. | −1·10 (−1·49 to −0·71) | |

| Individual CBT | 15 | 562 | −1·19 (−1·56 to −0·81) | .. | |

| Hope, Heimberg, and Turk model | 2 | 53 | .. | −1·02 (−1·42 to −0·62) | |

| Other (no model specified) | 6 | 163 | .. | −1·19 (−1·48 to −0·89) | |

| Clark and Wells cognitive therapy model | 3 | 97 | .. | −1·56 (−1·85 to −1·27) | |

| Clark and Wells cognitive therapy shortened sessions | 4 | 249 | .. | −0·97 (−1·21 to −0·74) | |

| Other psychological therapy | 7 | 182 | −0·36 (−0·84 to 0·12) | .. | |

| Interpersonal psychotherapy | 2 | 64 | .. | −0·43 (−0·83 to 0·04) | |

| Mindfulness training | 3 | 64 | .. | −0·39 (−0·82 to 0·03) | |

| Supportive therapy | 2 | 54 | .. | −0·26 (−0·72 to 0·20) | |

| Psychodynamic psychotherapy | 3 | 185 | −0·62 (−0·93 to −0·31) | .. | |

| Self-help with support | 16 | 748 | −0·86 (−1·36 to −0·36) | .. | |

| Book with support | 3 | 52 | .. | −0·85 (−1·17 to −0·53) | |

| Internet with support | 13 | 696 | .. | −0·88 (−1·04 to −0·71) | |

| Self-help without support | 9 | 406 | −0·75 (−1·25 to −0·26) | .. | |

| Book without support | 4 | 136 | .. | −0·84 (−1·08 to −0·60) | |

| Internet without support | 5 | 270 | .. | −0·66 (−0·94 to −0·39) | |

| Combined interventions | |||||

| Combined | 5 | 156 | −1·30 (−1·73 to −0·88) | .. | |

| Group CBT and moclobemide | 1 | 22 | .. | −1·23 (−1·72 to −0·74) | |

| Group CBT and fluoxetine | 1 | 59 | .. | −0·95 (−1·34 to −0·58) | |

| Group CBT and phenelzine | 1 | 32 | .. | −1·69 (−2·10 to −1·27) | |

| Psychodynamic and clonazepam | 1 | 29 | .. | −1·28 (−1·82 to −0·74) | |

| Paroxetine and clonazepam | 1 | 14 | .. | −1·35 (−1·93 to −0·79) | |

CBT=cognitive–behavioural therapy. CrI=credible interval. SMD=standardised mean difference. SNRI=serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. SSRI=selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor.

Figure 3.

Effect of each class of intervention compared with waitlist

Data are standardised mean difference and 95% credible intervals compared with waitlist as a reference. CBT=cognitive–behavioural therapy. SNRI=serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. SSRI=selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor.

All psychological interventions apart from promotion of exercise and other psychological therapies (supportive therapy, mindfulness, and interpersonal psychotherapy) had greater effects on outcomes than did waitlist (table; figure 3). In decreasing order of effect size, these were individual cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT; class effect SMD −1·19, 95% CrI −1·56 to −0·81), group CBT (−0·92, −1·33 to −0·51), exposure and social skills (−0·86, −1·42 to −0·29), self-help with support (−0·86, −1·36 to −0·36), self-help without support (−0·75, −1·25 to −0·26), and psychodynamic psychotherapy (−0·62, −0·93 to −0·31).

Compared with pill placebo, MAOIs (SMD −0·53, 95% CrI −1·06 to −0·01) and SSRIs and SNRIs (−0·44, −0·67 to −0·22) had greater effects on outcomes, and pill placebo itself had a greater effect than waitlist (−0·47, −0·71 to −0·23; figure 4). Of the psychological interventions, only individual CBT had a greater effect on outcomes than psychological placebo (SMD −0·56, 95% CrI −1·00 to −0·11). Individual CBT also had a greater effect than pill placebo (SMD −0·72, 95% CrI −1·13 to −0·30), psychodynamic psychotherapy (−0·56, −1·00 to −0·11), and other therapies (−0·82, −1·41 to −0·24; figure 4). Figure 4 also expresses these treatment effects on the probability of recovery (ie, no longer meeting criteria for diagnosis).

Figure 4.

Efficacy of classes of interventions

Classes of interventions are ordered according to efficacy ranking from largest mean effect (top, left) to smallest mean effect (bottom, right). Data in blue represent the effects on symptoms of social anxiety (SMD [95% CrI]); SMD less than 0 favours the intervention in the row. Data in green represent the effects on recovery (RR [95% CrI]); RR greater than 1 favours the intervention in the column. Significant results are shaded dark blue and dark green. CBT=cognitive–behavioural therapy. CrI=credible interval. EXER=promotion of exercise. EXPO=exposure and social skills. MAOI=monoamine oxidase inhibitors. NSSA=noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants. OTHER=other psychological therapy. PDPT=psychodynamic psychotherapy. PSYP=psychological placebo. RR=risk ratio. SHNS=self-help without support. SHWS=self-help with support. SMD=standardised mean difference. SNRI=serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. SSRI=selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor.

Of the pharmacological interventions, there were greater individual effects compared with waitlist for all SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline) and the SNRI venlafaxine. Effects of SSRIs and SNRIs were measured in 32 studies, and they were similar in magnitude within the class except for citalopram, which was assessed in two small studies; all individual SMDs were within 0·08 of the class SMD. Compared with waitlist, the effects of the MOAIs phenelzine (SMD −1·28, −1·57 to −0·98) and moclobemide (−0·74, −1·03 to −0·44) were also greater; however, only 125 people received phenelzine across five trials and the results might be overestimated. The large effect for phenelzine was dissimilar to the small effect for moclobemide (appendix B), which was the only other MAOI included in the analysis.

The most efficacious psychological interventions were individual CBT—following the Clark and Wells model (SMD −1·56, 95% CrI −1·85 to −1·27),14 the Hope, Heimberg and Turk model (−1·02, −1·42 to −0·62),15 and CBT not following a named manual (−1·19, −1·48 to −0·89)—and group enhanced CBT (−1·10, −1·49 to −0·71; table). Supported self-help was efficacious when provided via the internet (SMD −0·88, 95% CrI −1·04 to −0·71) or by book (−0·85, −1·17 to −0·53). Psychological placebo also had a greater effect than waitlist (SMD −0·63, 95% CrI −0·90 to −0·36), and its effect was comparable to psychodynamic psychotherapy (−0·62, −0·93 to −0·31).

Several drugs had greater effects on outcomes compared with pill placebo: clonazepam, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, moclobemide, paroxetine, phenelzine, sertraline, and venlafaxine (appendix B). Citalopram was the only included SSRI that did not have a greater effect than placebo. Of the psychological interventions, only Clark and Wells cognitive therapy model, Clark and Wells cognitive therapy model with shortened sessions, individual CBT, and group enhanced CBT had greater effects than psychological placebo. There was no consistent evidence of differential efficacy within pharmacotherapies. There was some evidence of differential efficacy within the psychological interventions. Individual CBT according to the Clark and Wells manual showed the most consistent evidence of greater effects, as suggested by non-overlapping 95% CrIs between this intervention and most other psychological intervention (table).

Combined interventions had greater effects on outcomes than waitlist overall (SMD −1·30, 95% CrI −1·73 to −0·88; table; figure 4), but the quality of the evidence was poor. Five different combinations of psychological and pharmacological interventions were assessed in one trial each; all reported large effects, but only 156 participants received combined interventions across all five trials. There was no evidence that combined interventions had greater effects than the leading monotherapies (table).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first time that psychological and pharmacological interventions for a mental health problem have been compared in network meta-analysis.16 The findings confirm that social anxiety disorder responds well to treatment, although many people continue to experience some symptoms after the end of the acute treatment phase.

Several classes of pharmacological and psychological intervention had greater effects on outcomes than did waitlist. Individual CBT and the class including SSRIs and SNRIs also had greater effects on outcomes than appropriate placebos, suggesting that they have specific effects. Psychological and pill placebo had greater effects than waitlist; investigation of these effects suggests that non-specific factors might account for about half the total effects of individual CBT and SSRIs. Comparisons between psychological interventions revealed some evidence of differential effects. In particular, individual CBT had a greater effect than psychodynamic psychotherapy and other psychological therapies (interpersonal psychotherapy, mindfulness, and supportive therapy). Many of the psychological treatments with large effects were versions of CBT (individual, group, or self-help), suggesting that CBT might be efficacious in a range of formats. Psychodynamic psychotherapy was also effective, although its effects were similar to psychological placebo.

Because pharmacological and psychological interventions were both efficacious, a logical question to ask is whether combined interventions might be more helpful than either intervention alone. Although large effect sizes were noted with combined treatments, only a few small studies were included, and there was no evidence that any combination was more efficacious than the leading pharmacological or psychological monotherapy in that combination.

There was little evidence of differential efficacy within or between classes of drugs. In the case of SSRIs and SNRIs, this finding is consistent with data from a previous network analysis, which showed no differences in efficacy but differences in tolerability.17 In the absence of convincing evidence for differential efficacy, differences in tolerability and side-effects are particularly important in the choice of treatment. SSRIs and SNRIs with a short half-life (eg, paroxetine and venlafaxine) are associated with the greatest risk of discontinuation effects, including effects during the treatment period and after the end of treatment.18, 19 Some side-effects such as increased agitation18 and sexual dysfunction20 can be especially distressing for people with social anxiety disorder, particularly if these effects are unexpected or if they reinforce existing worries. These issues should be discussed with patients before starting drug treatment.

We were not able to investigate whether immediate treatment effects persist or diminish in the long term because most trials stopped at the end of treatment. Findings from studies that have addressed this issue21, 22 suggest that most people who respond to a SSRI will relapse within a few months if the drug is discontinued after acute treatment, and about 25% of people who respond to SSRI treatment and continue drug treatment will relapse within 6 months. By contrast, the effects of psychological interventions are generally well maintained at follow-up,23 and participants can continue to apply new skills and make further gains after the end of acute treatment.24 For this reason, and because of the lower risk of side-effects, psychological interventions should be preferred over pharmacological interventions for initial treatment.25

This study has several limitations. There were only a few studies of moderate size for several included interventions, and some have only been tested by one or two research groups. We included a broad range of interventions, which varied in duration, and there might be unknown differences among participants in different trials. However, we did not identify any systematic differences in participant demographics or initial symptom severity. Direct and indirect results were consistent, which provides further support to the pooled results. Control conditions were heterogeneous and rarely described in detail. Future trials should more clearly describe what was intended and what was actually received by people in control conditions.26, 27 Statistical power might have been limited because we used scores after treatment rather than the change in scores and because we calculated effects conservatively, estimating effects accounting for dropout (eg, using last-observation-carried-forward) where possible. Conversely, pairwise analyses of small studies sometimes overestimate effects compared with large studies.28, 29 Uncertainty in mean effects (ie, large CrIs) suggests that more research would improve our understanding of how these treatments compare. Specifically, large trials that compare active interventions and independent replications would improve the precision of these estimates and increase confidence in their external validity. We included only outcomes at the end of treatment; trials comparing active interventions with controlled long-term follow-up would provide better evidence of sustained effects.

Data for cost-effectiveness and side-effects both affect choices, and a cost-effectiveness analysis will be reported elsewhere. Taking these factors into account, NICE recently concluded that individual CBT should be offered as the treatment of choice for social anxiety disorder. For individuals who decline individual CBT, a SSRI is recommended for people who would prefer drug treatment and CBT-based supported self-help is recommended for people who prefer another psychological intervention. Psychodynamic psychotherapy is recommended as a third-line option, and other drugs are recommended only for people who do not respond to initial treatments.25, 30 Thus, NICE recommendations are consistent with the results of this study, which suggests that increased access to treatment would reduce disability and improve quality of life for people with social anxiety disorder.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

EM-W, IM, KK, and SP received support from NICE. SD and AEA received support from the Centre for Clinical Practice (NICE), with funding from the NICE Clinical Guidelines Technical Support Unit, University of Bristol. DMC is a National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator and is supported by the Wellcome Trust (069777). We thank Sarah Stockton, who developed the electronic search strategy with input from the authors. We thank the Guideline Development Group for the NICE guideline Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment and treatment (Safi Afghan, Peter Armstrong, Madeleine Bennett, Sam Cartwright-Hatton, Cathy Creswell, Melanie Dix, Nick Hanlon, Andrea Malizia, Jane Roberts, Gareth Stephens, and Lusia Stopa). We received support from colleagues at the NCCMH, including Benedict Anigbogu, Nuala Ernest, Katherine Leggett, Kate Satrettin, Melinda Smith, Clare Taylor, and Craig Whittington. Several colleagues also provided helpful feedback, including Andrea Cipriani, Richard Heimberg, Ron Rapee, and Franklin Schneier.

Contributors

EM-W drafted the protocol with all authors. EM-W and KK assessed the eligibility of the studies for inclusion, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias. SD and AEA developed the statistical code with EM-W and IM, and SD did the analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings. EM-W drafted the manuscript, to which all authors contributed. SP obtained funding.

Declaration of interests

DMC is the developer of one of the versions of individual CBT that was shown to be efficacious. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Fehm L, Beesdo K, Jacobi F, Fiedler A. Social anxiety disorder above and below the diagnostic threshold: prevalence, comorbidity and impairment in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:257–265. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1205–1215. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ipser JC, Kariuki CM, Stein DJ. Pharmacotherapy for social anxiety disorder: a systematic review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8:235–257. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodebaugh TL, Holaway RM, Heimberg RG. The treatment of social anxiety disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:883–908. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayo-Wilson E, Montgomery P. Media-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural therapy (self-help) for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005330.pub4. CD005330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higgins JP, Green S eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org

- 8.Wei Y, Higgins JPT. Estimating within-study covariances in multivariate meta-analysis with multiple outcomes. Stat Med. 2013;32:1191–1205. doi: 10.1002/sim.5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dias S, Sutton AJ, Ades AE, Welton NJ. Evidence synthesis for decision making 2: a generalized linear ehaviour framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:607–617. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12458724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franchini AJ, Dias S, Ades AE, Jansen JP, Welton NJ. Accounting for correlation in network meta-analysis with multi-arm trials. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3:142–160. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lunn DJ, Thomas A, Best N, Spiegelhalter D. WinBUGS— a Bayesian modelling framework: concepts, structure, and extensibility. Stat Comput. 2000;10:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, Caldwell DM, Lu G, Ades AE. Evidence synthesis for decision making 4: inconsistency in networks of evidence based on randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:641–656. doi: 10.1177/0272989X12455847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heimberg RG, Horner KJ, Juster HR. Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Psychol Med. 1999;29:199–212. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz M, Hope DA, Schneier FR, editors. Social phobia: diagnosis, assessment and treatment. Guildford Press; New York: 1995. pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive–behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:741–756. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bafeta A, Trinquart L, Seror R, Ravaud P. Analysis of the systematic reviews process in reports of network meta-analyses: methodological systematic review. BMJ. 2013;347:f3675. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen RA, Gaynes BN, Gartlehner G, Moore CG, Tiwari R, Lohr KN. Efficacy and tolerability of second-generation antidepressants in social anxiety disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:170–179. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f4224a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Hoog SL, Ascroft RC, Krebs WB. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sir A, D'Souza RF, Uguz S. Randomized trial of sertraline versus venlafaxine XR in major depression: efficacy and discontinuation symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1312–1320. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregorian RS, Golden KA, Bahce A, Goodman C, Kwong WJ, Khan ZM. Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1577–1589. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montgomery SA, Nil R, Dürr-Pal N, Loft H, Boulenger JP. A 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of escitalopram for the prevention of generalized social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1270–1278. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein DJ, Versiani M, Hair T, Kumar R. Efficacy of paroxetine for relapse prevention in social anxiety disorder: a 24-week study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1111–1118. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haug TTB. Exposure therapy and sertraline in social phobia: 1-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:312–318. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.4.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mortberg E, Clark DM, Bejerot S. Intensive group cognitive therapy and individual cognitive therapy for social phobia: sustained improvement at 5-year follow-up. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:994–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pilling S, Mayo-Wilson E, Mavranezouli I, Kew K, Taylor C, Clark D. Recognition, assessment and treatment of social anxiety disorder: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2013;346:f2541. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant SP, Mayo-Wilson E, Melendez-Torres GJ, Montgomery P. Reporting quality of social and psychological intervention trials: a systematic review of reporting guidelines and trial publications. PloS One. 2013;8:e65442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montgomery P, Underhill K, Gardner F, Operario D, Mayo-Wilson E. The Oxford Implementation Index: a new tool for incorporating implementation data into systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:874–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Gilbody SM, Trikalinos TA, Churchill R, Wahlbeck K, Ioannidis JP. Comparison of large versus smaller randomized trials for mental health-related interventions. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:578–584. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barth J, Munder T, Gerger H. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: a network meta-analysis. PloS Med. 2013;10:e1001454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark DM, Pilling S, Mayo-Wilson E. Social anxiety disorder: the NICE guideline on the recognition, assessment and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Royal College of Psychiatrists; London: 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.