Abstract

Background:

Persistent primitive hypoglossal artery (PPHA), a remnant of embryonal circulation, is a rare variant of the posterior cerebral circulation. Seven prior cases of posterior circulation stroke in the setting of PPHA have been described in the literature, with all but one case being attributable to atherosclerotic embolization from the internal carotid artery (ICA) through the PPHA.

Case Description:

We report a unique case of a young male with a PPHA presenting with a “top of the basilar” syndrome following the repair of his atrial septal defect who underwent emergent revascularization via endovascular mechanical aspiration thrombectomy. The patient underwent a successful aspiration thrombectomy with significant improvement in his clinical exam.

Conclusions:

Considering the rarity of this persistent fetal anastamosis, it is important to be aware of the propensity for unusual presentations in the context of stroke, understand the management of the problem, and expeditiously treat the patient.

Keywords: Basilar Infarction, persistent primitive hypoglossal artery, thrombectomy

INTRODUCTION

Persistent primitive hypoglossal artery (PPHA), a remnant of embryonal circulation, is a rare variant of the posterior cerebral circulation. Seven prior cases of posterior circulation stroke in the setting of PPHA have been described in the literature, with all but one case being attributable to atherosclerotic embolization from the internal carotid artery (ICA) through the PPHA. We report a unique case of a young male with a PPHA presenting with a “top of the basilar” syndrome following the repair of his atrial septal defect (ASD) who underwent emergent revascularization via endovascular mechanical aspiration thrombectomy (MAT).

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old, previously neurologically intact, right-handed male presented 4 h after experiencing an acute neurological deterioration in which he was found unresponsive with flaccid extremities. He had undergone open surgical repair of an ASD 3 days prior. He was emergently intubated and transferred to our institution.

The patient was unresponsive to painful stimulation on examination, with an initial National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale of 28. A noncontrasted head computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a hyperdense basilar artery (BA), and a small focus of hypodensity in the posterior right temporal lobe, concerning for evolving right posterior ceberal artery (PCA) territory infarct. CT angiogram (CTA) confirmed the abrupt occlusion of the distal BA, and also showed a right-sided PPHA arising just distal to the right carotid bifurcation at the level of C3 vertebra, extending posteriorly through an enlarged hypoglossal canal to provide the predominant flow to the BA. In addition, the bilateral vertebral arteries were hypoplastic, and the right vertebral artery was not appreciated above the level of the C2 vertebra.

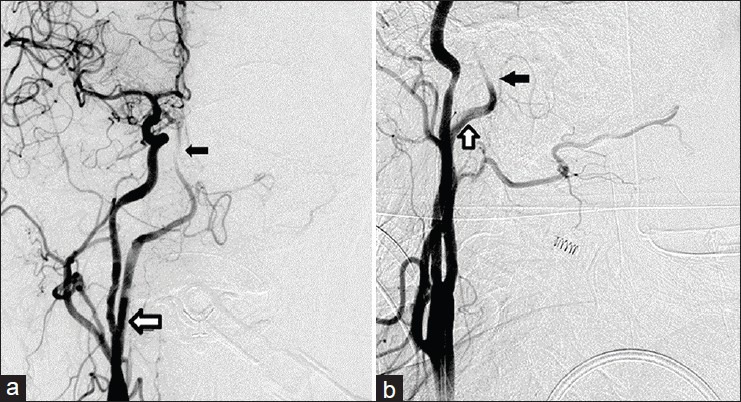

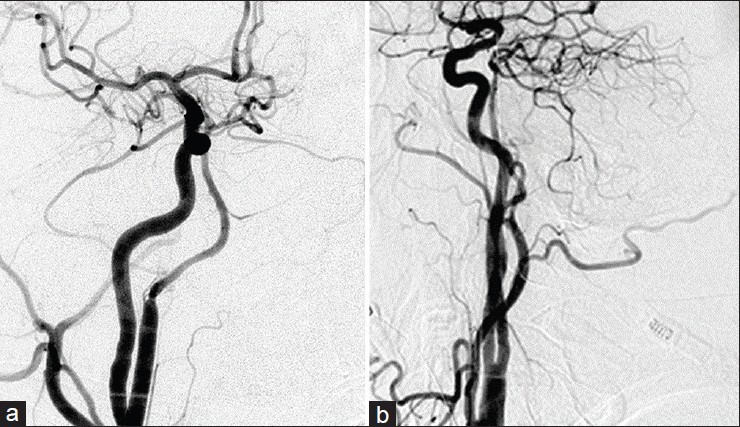

The patient was taken to the angiography suite for an emergent catheter-based cerebral arteriogram and revascularization. The right common carotid artery (CCA) arteriogram demonstrated a patent right internal and external carotid artery with retrograde filling through the right posterior communicating artery into the distal BA. The digital subtraction arteriogram also revealed the right PPHA originating at approximately the C2-3 disk space and an occlusion within the mid-portion of the BA, distal to the origin of the anterior inferior cerebellar arteries [Figure 1]. Subsequently, the diagnostic catheter was exchanged for a 0.88" Neuron MAX (Penumbra Inc., Alameda, CA) guide catheter, which was placed in the right CCA. Under roadmap guidance, a triaxial system consisting of a 0.058" Navien aspiration catheter (Covidien, Irivine, CA), an Orion microcatheter (Covidien, Irvine, CA), and Synchro2 microwire (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) was advanced into the proximal BA. The microwire and microcatheter were advanced through and past the thrombus into the right PCA, and, over this platform, the aspiration catheter was advanced into the thrombus within the BA. The microwire and microcatheter were removed and after two attempts of manual aspiration using a 20 cc syringe, complete revascularization of the BA was achieved, consistent with TICI 3 flow [Figure 2]. Groin puncture to recanalization time was 40 min.

Figure 1.

Digital subtraction angiography, AP (a) and lateral view (b), revealing the mid-basilar occlusion and the origin of the PPHA from the cervical segment of the ICA. The occlusion is marked with a small black arrow. The PPHA is marked with a white arrow

Figure 2.

Arteriogram following manual aspiration thrombectomy, showing full recanalization of the basilar artery, Towne's projection (a) and lateral view (b), consistent with TICI 3 flow

RESULTS

Postthrombectomy, the patient was aphasic, but could communicate by blinking; he followed commands in all four extremities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed infarct within the left superior cerebellar artery territory, including the left cerebellar hemisphere, pons, midbrain, left cerebral peduncle, and left thalamus with hemorrhage within the left peduncle and left thalamus.

DISCUSSION

With an incidence of 0.027–0.1%, the PPHA is the second most common of the four anomalous carotid-basilar anastomoses, which represent the persistence of embryological anastomoses between the carotid and vertebrobasilar system.[7] At 29 days of age, the human embryo has two longitudinal neural arteries arising along the surface of the hindbrain on both sides of the midline, which eventually fuse to form the BA.[5] The primitive hypoglossal artery is one of four presegmental branches of the dorsal aorta, which serve as anastomoses between the dorsal aorta and the bilateral longitudinal neural arteries.

The vascular anomaly described in this case is consistent with published diagnostic criteria for PPHA, namely that: (A) The hypoglossal artery arises as an extracranial branch of the ICA, (B) the artery passes through the hypoglossal canal, and (C) the BA originates from the hypoglossal artery.[4] Typically, PPHAs have a diameter of 4–7 mm, are unilateral and involve the left-sided circulation.[3,7] Patients with PPHA generally exhibit other abnormalities of the posterior circulation, and the hypoplastic left VA and distally absent right VA observed in the case described herein is consistent with the most common VA configurations seen with PPHA: 79–90% of PPHAs are associated with bilaterally hypoplastic VAs or with a hypoplastic VA on one side and an absent VA on the other.[2,7]

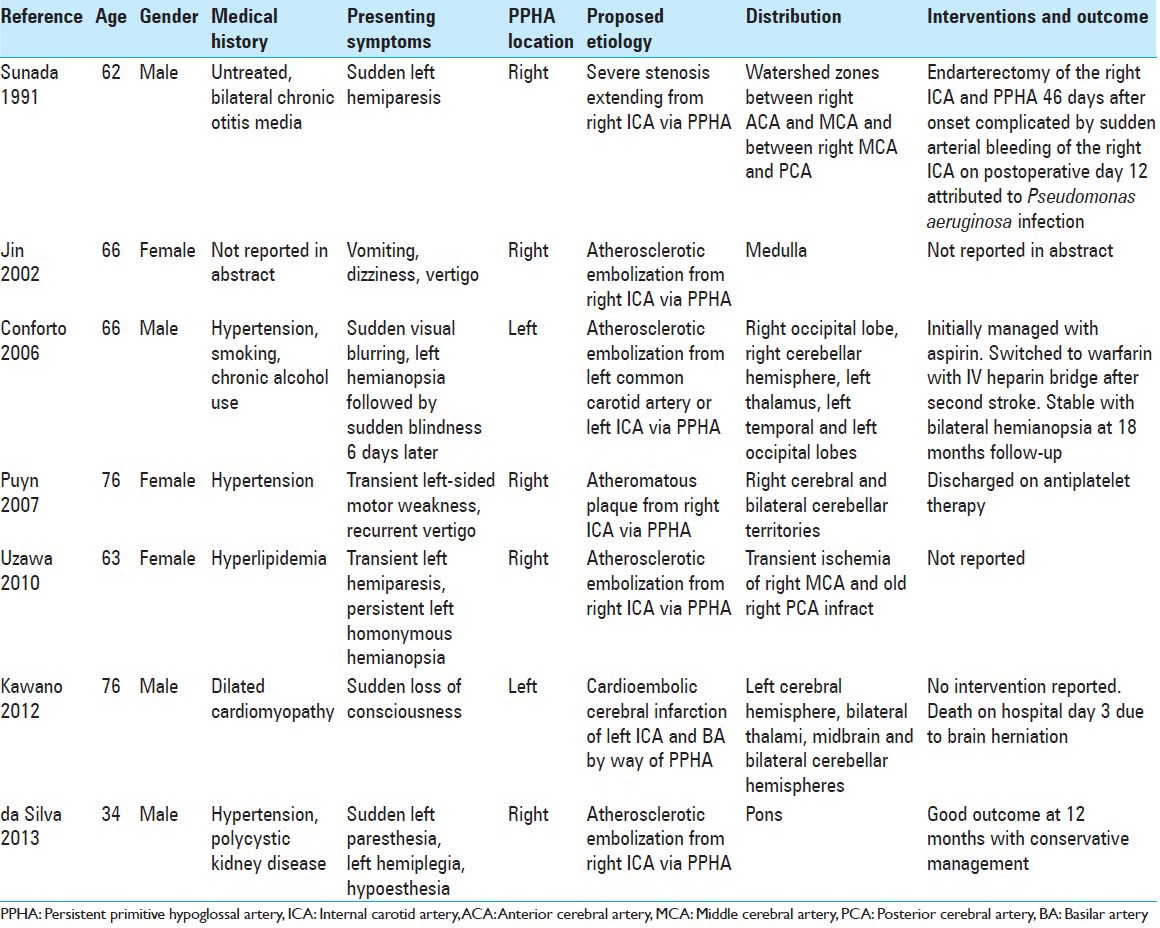

In the setting of ischemic stroke, the anomalous cerebrovascular anatomical patterns observed in patients with PPHA can result in complex presentations of neurological deficits, affecting both anterior and posterior circulations and suggestive of cardioembolic origin. In fact, the majority of cases of ischemic stroke in the setting of PPHA have been attributed to atherosclerotic vessel-to-vessel embolization from the ICA through the PPHA, resulting in infarct distribution affecting both anterior and posterior circulations [Table 1]. Unlike the majority of the previously reported cases, our patient was significantly younger, did not have extensive cardiovascular risk factors and did not demonstrate evidence of high-grade stenosis of the carotid vasculature.

Table 1.

Summary of previous reports of stroke in the setting of PPHA as diagnosed by the Brismar criteria

To date, there are few cases of stroke patients with persistent primitive carotid-basilar anastomoses undergoing revascularization procedures. Sunada et al. reported on the only case of revascularization for stroke in the setting of a PPHA, where a 62-year-old male underwent an endarterectomy of the ICA and PPHA 46 days after presenting with persistent left hemiparesis in the setting of marked stenosis extending from the origin of the ICA to the PPHA.[6] Abla et al. reported on a case of left ECA and subclavian stent placement in the setting of a proatlantal intersegmental artery (PIA) 3 days after a right PCA distribution stroke attributed to embolization from the left ECA through the PIA.[1] These procedures were performed in a subacute fashion, in contrast to our case in which we performed emergent MAT in the setting of an acute stroke.

CONCLUSIONS

Our case of a young patient with a PPHA experiencing a “top of the basilar” syndrome after ASD correction and emergent revascularization via endovascular MAT is unique to the literature. Considering the rarity of this persistent fetal anastamosis, it is important to be aware of the propensity for unusual presentations in the context of stroke, understand the management of the problem, and expeditiously treat the patient.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.surgicalneurologyint.com/text.asp?2014/5/1/182/147412

Contributor Information

Zoya Voronovich, Email: voronovichz@upmc.edu.

Ramesh Grandhi, Email: grandhir@upmc.edu.

Nathan T. Zwagerman, Email: zwagermannt@upmc.edu.

Ashutosh P. Jadhav, Email: jadhavap@upmc.edu.

Tudor G. Jovin, Email: jovitg@upmc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abla AA, Kan P, Jahshan S, Dumont TM, Levy EI, Siddiqui AH. External carotid dissection and external carotid proatlantal intersegmental artery with subclavian steal prompting external carotid and subclavian artery stenting. J Neuroimaging. 2014;24:399–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2012.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agnoli AL. Vascular anomalies and subarachnoid haemorrhage associated with persisting embryonic vessels. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1982;60:183–99. doi: 10.1007/BF01406306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnould G, Tridon P, Laxenaire M, Picard L, Weber M, Gougaud G. The primitive hypoglossal artery. Anatomic and radio-clinical study. Apropos of 2 cases. Rev Neurol. 1968;118:372–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brismar J. Persistent hypoglossal artery, diagnostic criteria. Report of a case. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1976;17:160–6. doi: 10.1177/028418517601700204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padget DH. The development of the cranial arteries. Contrib Embryol. 1948;32:207–61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sunada I, Yamamoto S, Matsuoka Y, Nishimura S. Endarterectomy for persistent primitive hypoglossal artery-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1991;31:104–8. doi: 10.2176/nmc.31.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasović L, Milenković Z, Jovanović I, Cukuranović R, Jovanović P, Stefanović I. Hypoglossal artery: A review of normal and pathological features. Neurosurg Rev. 2008;31:385–95. doi: 10.1007/s10143-008-0145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]