Abstract

The clinical phenotypes of patients with Bartter syndrome type III sometimes closely resemble those of Gitelman syndrome. We report a patient with mild, adult-onset symptoms, such as muscular weakness and fatigue, who showed hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, elevated renin–aldosterone levels with normal blood pressure, hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia. She was also suffering from chondrocalcinosis. A diuretic test with furosemide and thiazide showed a good response to furosemide, but little response to thiazide. Although the clinical findings and diuretic tests predicted that the patient had Gitelman syndrome, genetic analysis found no mutation in SLC12A3. However, a novel missense mutation, p.L647F in CLCNKB, which is located in the CBS domain at the C-terminus of ClC-Kb, was discovered. Therefore, gene analyses of CLCNKB and SLC12A3 might be necessary to elucidate the precise etiology of the salt-losing tubulopathies regardless of the results of diuretic tests.

Keywords: Bartter syndrome type III, ClC-Kb, CLCNKB, Gitelman syndrome, Hydrochlorothiazide, Chondrocalcinosis

Highlights

-

•

We report a patient of Gitelman-like phenotype with chondrocalcinosis.

-

•

She also showed the insensitivity to thiazide.

-

•

No mutation in SLC12A3, but a novel mutation, L647F in CLCNKB was discovered.

-

•

The L647F located in the CBS domain of ClC-Kb.

-

•

Molecular gene analysis of CLCNKB and SLC12A3 is necessary to the precise etiology.

Introduction

Bartter syndrome is an autosomal inherited disorder with clinical characteristics including renal salt wasting, hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, elevated renin–aldosterone levels with normal or low blood pressure, hypercalciuria and normal serum magnesium levels (Bartter et al., 1962). The last two features distinguish Bartter's patients from patients with Gitelman syndrome (Gitelman et al., 1966), who, in addition to hypokalemic alkalosis and salt wasting, have hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia (Bianchetti et al., 1992). Furthermore, a diuretic test with oral hydrochlorothiazide allows Gitelman syndrome to be differentiated from Bartter syndrome in clinical practice (Tsukamoto et al., 1995, Colussi et al., 2007).

These syndromes are caused by mutations in genes encoding channels and transporters involved in electrolyte transport along the nephron. Using linkage analyses of family members, highly significant associations were established between the genes encoding the thick ascending limb (TAL) transporter, SLC12A1 (Simon et al., 1996a), KCNJ1 (Simon et al., 1996b) and CLCNKB (Simon et al., 1997) in Bartter syndrome, which were named as Bartter syndrome type I, type II and type III, respectively. The distal convoluted tubule (DCT) Na-Cl co-transporter gene, SLC12A3 (Simon et al., 1996c) is significantly associated with Gitelman syndrome.

It is evident that the clinical phenotype in patients with CLCNKB mutations can be highly variable, from antenatal onset of Bartter syndrome to a phenotype closely resembling Gitelman syndrome (Konrad et al., 2000, Jeck et al., 2000, Zelikovic et al., 2003). Clinical overlap of symptoms between Bartter syndrome and Gitelman syndrome is occasionally observed, such that a diuretic test using furosemide and thiazide is still sometimes used to obtain a differential diagnosis between the two syndromes (Tsukamoto et al., 1995, Colussi et al., 2007).

Here, we identified a novel missense mutation in CLCNKB in a Japanese patient, who presented a Gitelman's phenotype with hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia accompanied by chondrocalcinosis, and was insensitive to thiazide administration.

Patient and methods

Patient

A 45-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital in November 2005 for general fatigue, muscle weakness and hypokalemia. She denied vomiting or diarrhea. She was born at term without hydramnios. Her birth weight was 3030 g. She had felt pain on her knee joint at age 36 and underwent operation of the right knee joint at age 37. She felt numbness on right face and right arm, general fatigue and muscle weakness from age 45. She has experienced no carpopedal spasms. Although hypokalemia was noted before an operation on her right knee joint at age 37, no further studies were conducted at that time. She had not taken magnesium and sodium supplementation or high sodium diet. The patient was a smoker (10 cigarettes/day). Her height and body weight were 161 cm and 39 kg, respectively. Her blood pressure was 102/85 mm Hg, and her grip in both hands was weak. Laboratory findings revealed slightly low serum sodium and chloride levels, but extremely low serum potassium (2.3 mmol/L) and low serum magnesium (1.5 mg/dL) (Table 1). Urine osmolality determined in 24-hour urine ranged from 253 to 421 mOsm/L. Although urinary sodium, chloride and potassium excretion were almost in the normal range, urinary calcium excretion was low (Ca/Cr 0.025 g/gCr). She showed obvious metabolic alkalosis; pH 7.51, bicarbonate 45.3 mmol/L, base excess 18.5 mmol/L. Renin activity (PRA) and aldosterone in her plasma were more than 20 ng/mL/h and 310 pg/mL, respectively.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings of the patient.

| Result | Normal range | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Na | 136 | 138–146 | (mEq/L) |

| K | 2.3 | 3.6–4.9 | (mEq/L) |

| Cl | 88 | 99–109 | (mEq/L) |

| Ca | 9.6 | 8.7–10.3 | (mg/dL) |

| Mg | 1.5 | 1.8–2.5 | (mg/dL) |

| pH | 7.51 | 7.35–7.45 | |

| HCO3− | 45.3 | 21–28 | (mmol/L) |

| Creatinine | 0.6 | 0.4–0.7 | (mg/dL) |

| PRA | > 20 | 0.3–2.9 | (ng/mL/h) |

| Aldosterone | 310 | 29.9–159 | (pg/mL) |

| Urine Na | 62 | 70–250 | (mEq/day) |

| Urine K | 24 | 25–100 | (mEq/day) |

| Urine Cl | 74 | 70–250 | (mEq/day) |

| Urine Ca | 50 | 150–290 | (mg/day) |

| Urine Mg | 64 | 20–130 | (mg/day) |

| Urine Ca/Cr | 0.025 | 0.05–0.15 | (g/g · Cr) |

| Creatinine clearance | 63 | 81–137 | (mL/min) |

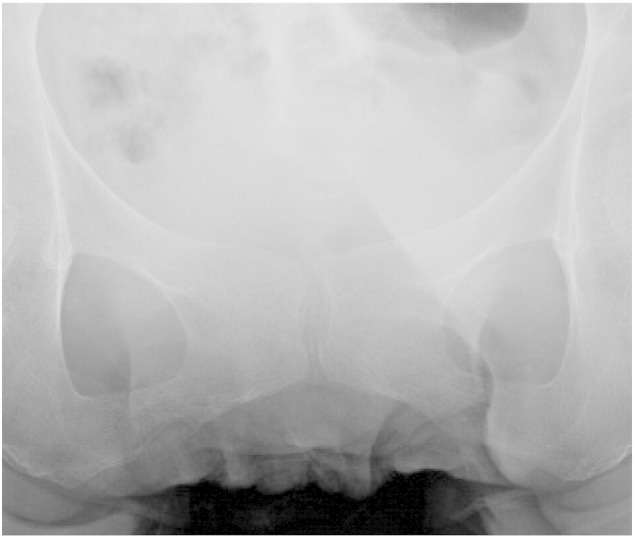

Conventional radiography

Conventional radiography of the antero-posterior view of pelvis showed calcifications in symphysis pubis in the patient (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Conventional radiography of the antero-posterior view of pelvis in the patient.

Diuretic tests

The patient underwent diuretic tests according to a protocol described by Tsukamoto et al. (1995) and Colussi et al. (2007). She drank water at 30 mL/kg, followed by intra-venous infusion of a 5% of glucose solution at a rate of 200 mL/h to generate sufficient urinary flow. When urinary flow reached 10 mL/min, samples of urine and serum were obtained to calculate the maximal free water clearance. Subsequently, 20 mg of furosemide (intravenously) or 100 mg of hydrochlorothiazide (orally) was administrated. Samples were collected when urinary flow reached the maximum. Osmolar clearance, maximal free water clearance, chloride clearance and distal fractional chloride reabsorption were calculated. The results were compared to control data from previously published reports (Puschett et al., 1988, Zarraga Larrondo et al., 1992).

Gene analysis

Total DNA was extracted and purified from peripheral leukocytes in a whole-blood sample using a SepaGene DNA extraction kit (WAKO, Japan) (Ohkubo et al., 2005). All the exons in the coding regions and the flanking intron–exon boundaries of CLCNKB and SLC12A3, and 2 kb from the 5′ promoter region of SLC12A3, were amplified using the specific PCR primers respectively [Supplementary Data Table 1, Supplementary Data Table 2, Supplementary Data Table 3]. The DNA was amplified by PfuUltra II Fusion HS DNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies, CA) or TaKaRa LA Taq DNA Polymerase (TaKaRa BIO, Japan) setting the annealing temperatures to those in Supplementary Tables. The PCR-amplified products were then purified using QIA quick PCR amplification kit (QIAGEN, Germany). The sequencing reactions were carried out using the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, CA) and reaction products were analyzed on an ABI-Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, CA) (Ohkubo et al., 2005).

MLPA analysis

We used the SALSA MLPA kit P136 SLC12A3 and P266 CLCNKB (MRC Holland, the Netherlands) for the search of genomic rearrangements. The procedure was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ligation products were separated on an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, CA). The analysis was performed using GeneMapper v 4.0 (Applied Biosystems, CA).

Mutation analysis

The functional consequence of the mutation was predicted with web server, Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT; http://sift.jcvi.org/) (Sim et al., 2012) and Polymorphism Phenotyping (PolyPhen2; http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) (Adzhubei et al., 2010).

Results

Diuretic tests

As shown in Table 2, the maximal free water clearance per 100 mL glomerular filtration rate (CH2O) and chloride clearance per 100 mL glomerular filtration rate (CCl) were moderately reduced. The distal fractional chloride reabsorption [CH2O / (CH2O + CCl)] was in normal range. Moreover, the patient responded well to furosemide, inducing an approximately 160-fold increase in chloride clearance (CCl). By contrast, hydrochlorothiazide did not significantly induce chloride excretion. Distal fractional chloride reabsorption [CH2O / (CH2O + CCl)] was apparently decreased by acute furosemide administration, whereas thiazide ingestion had little effect on this parameter.

Table 2.

Diuretic tests of fractional chloride reabsorption.

| CH2Oa |

CClb |

CH2O/(CH2O + CCl)c |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| (mL/min/100 mL GFR) | (mL/min/100 mL GFR) | (%) | |

| Before tolerance | 6.2 | 0.1 | 98.4 |

| Furosemide (20 mg iv) | 12.5 | 16.1 | 43.9 |

| Thiazide (100 mg po) | 3.6 | 0.6 | 85.7 |

Water clearance per 100 mL glomerular filtration rate.

Chloride clearance per 100 mL glomerular filtration rate.

Distal fractional chloride reabsorption.

Gene analysis

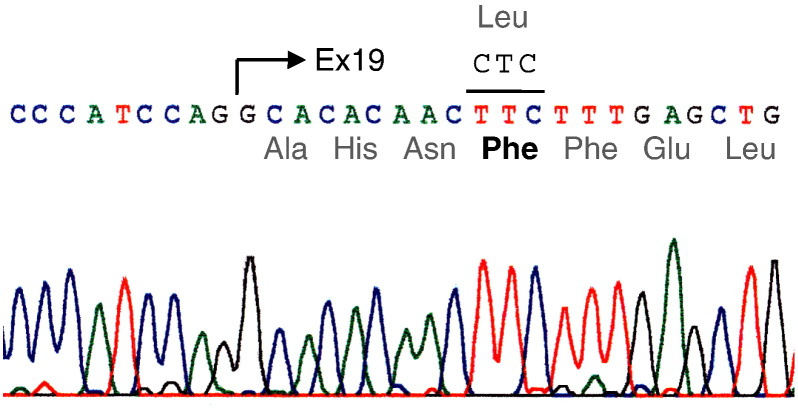

A homozygous mutation in CLCNKB was identified in the patient (Fig. 2), where a cytosine was substituted by thymine (c.1939 C > T) in exon 19 of CLCNKB, such that the amino acid of codon 647 was changed from leucine to phenylalanine (p.Leu647Phe). No mutation was detected in the 5′ upstream region or the coding region of SLC12A3, mutations in which are responsible for Gitelman syndrome.

Fig. 2.

Gene analysis by direct sequencing of the PCR product of exon 19 in CLCNKB in the patient.

From the results of MLPA analysis, no genomic rearrangement was identified in the region of SLC12A3 or CLCNKB.

Mutation analysis

The SIFT algorithm predicted p.Leu647Phe was deleterious to effect protein function with a score of 0.01. The PolyPhen-2 also predicted that this mutation was probably damaging with a score of 0.999.

Clinical course

The patient was treated with potassium chloride (56 mEq/day) and spironolactone (50 mg/day). Her plasma potassium increased from 2.2 mEq/L to 3.0 mEq/L within a month, following a disappearance of symptoms.

Discussion

The clinical symptoms, laboratory data and the results of the diuretic test of this patient all suggested that she was suffering from Gitelman syndrome. Especially, she had felt joint pain in knee and shoulder from age 30's. Conventional radiograph revealed calcification in symphysis pubis although no abnormal findings existed in knee or shoulder joint. It might be caused by calcium pyrophosphate deposition suggesting chondrocalcinosis, which was seen in the patients showing hypomagnesemia and hypocalciuria, who were diagnosed as Gitelman syndrome or Bartter syndrome (Gupta et al., 2005, Favero et al., 2011). However, there was no pathological gene mutation and deletion in the coding region or 5′ promoter region of SLC12A3 in her genome. Further genetic analysis revealed a missense mutation at codon 647 in exon 19 of CLCNKB, which caused leucine to be substituted by phenylalanine. The patient was homozygous for this mutation, because of normal allele dosage shown by MLPA analysis. Therefore, she was diagnosed as Bartter syndrome type III, on the basis of the mutation in CLCNKB.

Bartter syndrome type III (Simon et al., 1997, Konrad et al., 2000), which is classified as classic Bartter syndrome (Konrad et al., 2000), often occurs in infants, showing polydipsia and polyuria, or failure to thrive. Nephrocalcinosis or severe renal failure is rare. Hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia are often recognized. A differential diagnosis between Gitelman syndrome and Bartter syndrome type III can be difficult using the results of the examinations of blood chemistry and laboratory tests even though the patients have secondary complication, chondrocalcinosis (Favero et al., 2011). Therefore, genetic analysis is necessary to elucidate the precise etiology of the disease as they may show Gitelman-like symptoms.

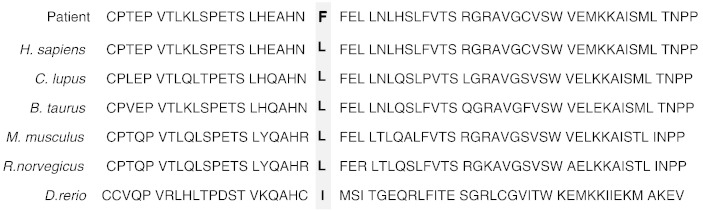

The novel mutation in this patient, p.Leu647Phe, is located at one of the cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS pair) domains (Ignoul and Eggermont, 2005) in the C-terminus of the chloride channel protein ClC-Kb. This leucine is not only highly conserved between ClC-Ka and ClC-Kb (Kieferle et al., 1994), but is also conserved among ClC chloride channels of vertebrates except Danio rerio, where the amino acid is isoleucine (Fig. 3). It is suggested that this mutation may have a serious effect on the chloride transport function of ClC-Kb, which was predicted by SIFT and PolyPhen2. This is the first case report of a missense mutation in CLCNKB in a patient who showed a normal response to furosemide and little response to thiazide. The distribution of ClC-Kb in the kidney is broad, from the TAL of the loop of Henle to DCT (Yoshikawa et al., 1999, Kobayashi et al., 2001). Defects in ClC-Kb resulting from a CLCNKB mutation might cause secondary dysfunction of thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride cotransporter NCCT and downregulation of the expression of a member of transient receptor-potential ion-channel family, TRPM6, which may result in renal magnesium wasting at DCT and induce hypomagnesemia (Nijenhuis et al., 2005). On the other hand, ClC-Ka, which has about 90% amino acid sequence similarity with ClC-Kb, is distributed also in the TAL with predominant expression in the thin ascending limb of the loop of Henle (Uchida et al., 1995, Mejia and Wade, 2002). The mouse ClC-K1, which is equivalent to human ClC-Ka, might also mediate some of the diuretic effects of furosemide, as indicated in an in vitro expression study using Xenopus oocytes (Uchida et al., 1995) and an in vivo study in rats (Wolf et al., 2003). In the diuretic test, this patient showed a good response to furosemide, which might represent normal chloride transport by chloride channels in the TAL, including ClC-Ka. It is thus suggested that in the TAL, ClC-Ka might compensate for the dysfunction of the mutant ClC-Kb and the major defects might be discovered in the distal tubules, where such compensation by ClC-Ka did not exist (Schlingmann et al., 2004, Krämer et al., 2008). Therefore, the phenotype of this patient might be quite similar to that of Gitelman syndrome. Nevertheless, there was the phenotype variability from Gitelman syndrome to classic Bartter syndrome in patients with CLCNKB mutations (Jeck et al., 2000), even having the same mutation in one family (Zelikovic et al., 2003). It might be speculated that it depended on individual differences in distribution of ClC-Kb in the distal nephron or a possibility for activating alternative routes of basolateral chloride secretion to compensate the ClC-Kb defect.

Fig. 3.

The amino-acid sequence alignment of the CBS2 domain in the chloride channel proteins from different species.

Recently, Seyberth and Schlinmann (2011) suggested a new terminology and pharmacological classification of salt-losing tubulopathies with loop or DCT defects. In this classification, Gitelman syndrome is classified as the pure thiazide type (DC1 type), which is caused by inactivating mutations in SLC12A3, and Bartter syndrome type III is classified as the mixed thiazide-furosemide type (DC2 type) by CLCNKB mutations. This classification defines the affected sites in the distal nephron and the etiological gene mutations, in contrast to classical typing of antenatal, classical Bartter syndrome and Gitelman syndrome. However, the majority of patients with the DC2 type share symptoms with the pure thiazide type of disorder, DC1 type, making it difficult to differentiate two types, except by genetic analysis.

There is a report of nine Japanese patients that showed the same discrepancies between the diuretic tests and genotypes as this patient. All of them were antenatal or classical Bartter syndrome and had homotypes of nonsense mutations (W391X, W610X), a compound heterotype of nonsense mutations (R76X/W610X) or a mixed type of deletion and nonsense mutation (Exons 1–2 deletion/W610X) (Nozu et al., 2010). The authors considered the reasons why those patients showed a poor response to thiazide, although Colussi et al. (2007) reported that two patients of type III Bartter syndrome showed a good response to thiazide. They suggested that the truncation mutation in their patients might cause a more severe dysfunction of the channel than missense or in-frame deletion mutations, as seen in Colussi's report. Although our patient had a missense mutation, this mutation might severely affect the function of the channel, because of the substitution of the important amino acid in the CBS domain of ClC-Kb C-terminal.

In conclusion, a novel missense mutation, p.Leu647Phe, in the CBS domain of ClC-Kb caused a phenotype that showed a postnatal (adult-onset) manifestation, a preserved renal concentrating capacity, low plasma levels of magnesium, and diuretic insensitivity to thiazide administration and also suffered from chondrocalcinosis secondary due to hypomagnesemia. These symptoms make it quite difficult to differentiate Bartter syndrome type III from Gitelman syndrome, such that genetic analysis is necessary to correctly diagnose the etiology of the salt-losing tubulopathies.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

List of PCR primers used for amplifying exons and flanking intron regions of CLCNKB.

List of PCR primers used for amplifying exons and flanking intron regions of SLC12A3.

List of PCR primers used for amplifying 5′ promoter regions of SLC12A3.

References

- Adzhubei I.A., Schmidt S., Peshkin L. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartter F.C., Pronove P., Gill J.R., MacCardle R.C., Diller E. Hyperplasia of the juxtaglomerular complex with hyperaldosteronism and hypokalemic alkalosis: a new syndrome. Am. J. Med. 1962;33:811–828. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(62)90214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchetti M.G., Bettinelli A., Oetliker O.H., Sereni F. Calciuria in Bartter's and similar syndromes. Clin. Nephrol. 1992;38(6):338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colussi G., Bettinelli A., Tedeschi S. A thiazide test for the diagnosis of renal tubular hypokalemic disorders. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007;2(3):454–460. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02950906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favero M., Calo L.A., Schiavon F., Punzi L. Bartter's and Gitelman's disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2011;25:637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitelman H.J., Graham J.B., Welt L.G. A new familial disorder characterized by hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia. Trans. Assoc. Am. Phys. 1966;79:221–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R., Hu V., Reynolds T., Harrison R. Sclerochoroidal calcification associated with Gitelman syndrome and calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate deposition. J. Clin. Pathol. 2005;58:1334–1335. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.027300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignoul S., Eggermont J. CBS domains: structure, function, and pathology in human proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2005;289(6):C1369–C1378. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00282.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeck N., Konrad M., Peters M. Mutations in the chloride channel gene, CLCNKB, leading to a mixed Bartter–Gitelman phenotype. Pediatr. Res. 2000;48(6):754–758. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200012000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieferle S., Fong P., Bens M., Vandewalle A., Jentsch T.J. Two highly homologous members of the ClC chloride channel family in both rat and human kidney. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91(15):6943–6947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Uchida S., Mizutani S., Sasaki S., Marumo F. Intrarenal and cellular localization of CLC-K2 protein in the mouse kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2001;12(7):1327–1334. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1271327. (Jul) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad M., Vollmer M., Lemmink H.H. Mutations in the chloride channel gene CLCNKB as a cause of classic Bartter syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2000;11(8):1449–1459. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1181449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krämer B.K., Bergler T., Stoelcker B., Waldegger S. Mechanisms of disease: the kidney-specific chloride channels ClCKA and ClCKB, the Barttin subunit, and their clinical relevance. Nat. Clin. Pract. Nephrol. 2008;4(1):38–46. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia R., Wade J.B. Immunomorphometric study of rat renal inner medulla. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2002;282(3):F553–F557. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00340.2000. (Mar) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijenhuis T., Vallon V., van der Kemp A.W. Enhanced passive Ca2 + reabsorption and reduced Mg2 + channel abundance explains thiazide-induced hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115(6):1651–1658. doi: 10.1172/JCI24134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozu K., Iijima K., Kanda K. The pharmacological characteristics of molecular-based inherited salt-losing tubulopathies. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95(12):E511–E518. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo K., Nagashima M., Naito Y. Genotypes of the pancreatic β-cell K-ATP channel and clinical phenotypes of Japanese patients with persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia of infancy. Clin. Endocrinol. 2005;62:458–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puschett J.B., Greenberg A., Mitro R., Piraino B., Wallia R. Variant of Bartter's syndrome with a distal tubular rather than loop of Henle defect. Nephron. 1988;50(3):205–211. doi: 10.1159/000185159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlingmann K.P., Konrad M., Jeck N., Waldegger P., Reinalter S.C., Holder M., Seyberth H.W., Waldegger S. Salt wasting and deafness resulting from mutations in two chloride channels. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350(13):1314–1319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032843. (Mar 25) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyberth H.W., Schlinmann K.P. Bartter–Gitelman-like syndromes: salt-losing tubulopathies with loop or DCT defect. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2011;26(10):1789–1802. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim N.-L., Kumer P., Hu J. SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(W1):W452–W457. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D.B., Karet F.E., Hamdan J.M. Bartter's syndrome, hypokalaemic alkalosis with hypercalciuria, is caused by mutations in the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC2. Nat. Genet. 1996;13(2):183–188. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D.B., Karet F.E., Rodriguez-Soriano J. Genetic heterogeneity of Bartter's syndrome revealed by mutations in the K + channel, ROMK. Nat. Genet. 1996;14(2):152–156. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D.B., Nelson-Williams C., Bia M.J. Gitelman's variant of Bartter's syndrome, inherited hypokalaemic alkalosis, is caused by mutations in the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter. Nat. Genet. 1996;12(1):24–30. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D.B., Bindra R.S., Mansfield T.A. Mutations in the chloride channel gene, CLCNKB, cause Bartter's syndrome type III. Nat. Genet. 1997;17(2):171–178. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto T., Kobayashi T., Kawamoto K., Fukase M., Chihara K. Possible discrimination of Gitelman's syndrome from Bartter's syndrome by renal clearance study: report of two cases. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1995;25(4):637–641. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida S., Sasaki S., Nitta K., Uchida K., Horita S., Nihei H., Marumo F. Localization and functional characterization of rat kidney-specific chloride channel, ClC-K1. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;95(1):104–113. doi: 10.1172/JCI117626. (Jan) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf K., Meier-Meitinger M., Bergler T. Parallel down-regulation of chloride channel CLC-K1 and Barttin mRNA in the thin ascending limb of the rat nephron by furosemide. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446(6):665–671. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa M., Uchida S., Yamauchi A., Miyai A., Tanaka Y., Sasaki S., Maruno F. Localization of rat CLC-K2 chloride channel mRNA in the kidney. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:F552–F558. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.4.F552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarraga Larrondo S., Vallo A., Gainza J. Familial hypokalemia–hypomagnesemia or Gitelman's syndrome: a further case. Nephron. 1992;62(3):340–344. doi: 10.1159/000187070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelikovic I., Szargel R., Hawash A. A novel mutation in the chloride channel gene, CLCNKB, as a cause of Gitelman and Bartter syndromes. Kidney Int. 2003;63(1):24–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of PCR primers used for amplifying exons and flanking intron regions of CLCNKB.

List of PCR primers used for amplifying exons and flanking intron regions of SLC12A3.

List of PCR primers used for amplifying 5′ promoter regions of SLC12A3.