Abstract

Objective

The application of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) has changed treatment paradigms for thoracic aortic disease. We sought to better define specific treatment patterns and outcomes for type B aortic dissection treated with TEVAR or open surgical repair (OSR).

Methods

Medicare patients undergoing type B thoracic aortic dissection repair (2000–2010) were identified by use of a validated International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnostic and procedural code–based algorithm. Trends in utilization were analyzed by procedure type (OSR vs TEVAR), and patterns in patient characteristics and outcomes were examined.

Results

Total thoracic aortic dissection repairs increased by 21% between 2000 and 2010 (2.5 to 3 per 100,000 Medicare patients; P = .001). A concomitant increase in TEVAR was seen during the same interval (0.03 to 0.8 per 100,000; P < .001). By 2010, TEVAR represented 27% of all repairs. TEVAR patients had higher rates of comorbid congestive heart failure (12% vs 9%; P < .001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (17% vs 10%; P < .001), diabetes (8% vs 5%; P < .001), and chronic renal failure (8% vs 3%; P < .001) compared with OSR patients. For all repairs, patient comorbidity burden increased over time (mean Charlson comorbidity score of 0.79 in 2000, 1.10 in 2010; P = .04). During this same interval, in-hospital mortality rates declined from 47% to 23% (P < .001), a trend seen in both TEVAR and OSR patients. Whereas in-hospital mortality rates and 3-year survival were similar between patients selected for TEVAR and OSR, there was a trend toward women having slightly lower 3-year survival after TEVAR (60% women vs 63% men; P = .07).

Conclusions

Surgical treatment of type B aortic dissection has increased over time, reflecting an increase in the utilization of TEVAR. Overall, type B dissection repairs are currently performed at lower mortality risk in patients with more comorbidities.

Definitive management of Stanford type B thoracic aortic dissection remains a clinical challenge. This challenge arises from the wide variations in patient presentations and symptoms encountered in thoracic dissections and differing provider-specific thresholds for intervention. In the acute setting, open surgical repair (OSR) has been the historical standard of treatment for type B dissection complicated by organ malperfusion, intractable pain, uncontrollable hypertension, potential impending rupture, or rapid growth.1 However, in-hospital mortality rates for patients undergoing OSR for acute type B dissection are as high as 29% to 34%.2–4 After the introduction of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR), endovascular techniques have been incorporated into treatment paradigms for acute, complicated type B dissection to prevent rupture or end-organ damage.1,5–7 Furthermore, TEVAR has recently been used in the setting of chronic type B dissection to prevent and to treat aneurysmal degeneration,8–10 thus potentially expanding the patient population considered for intervention.

The introduction of TEVAR has led to an increasing rate of overall repairs in patients with thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms.11 However, it remains unclear how endovascular stent grafting has affected practice patterns for the treatment of type B dissection. Reports on patient characteristics and outcomes after repair of type B dissection largely remain limited to single-center series and registries.3,6,7 Results from two large population-based cohorts have been reported, but these reflected relatively short time intervals, spanning 3 years or less.12,13

Therefore, we sought to examine how TEVAR has changed the trends and outcomes in repair of type B dissection across the United States. We studied all patients undergoing repair of type B dissection in the U.S. Medicare population during a 10-year period, examining trends in utilization as well as differences in patient characteristics and outcomes.

METHODS

Database and cohort assembly

The database used for this analysis was the Medicare Physician/Supplier File and the Medicare Denominator File for the years 2000 to 2010. First, all patients with a diagnosis of thoracic aortic dissection were identified by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes 441.0, 441.01, and 441.03. Next, ICD-9 procedure codes were used to identify all patients with a diagnosis of thoracic aortic dissection who underwent either OSR (38.35 and 38.45) or TEVAR (39.79 and 39.73; Supplementary Table, online only).

All patients with a concomitant diagnosis of thoracic aortic aneurysm were excluded as many of these were likely to represent patients treated for chronic dissection with aneurysmal degeneration. In addition, to remove Stanford type A dissections from the database, patients with concomitant procedure codes for valve replacement, coronary artery bypass graft, aortic arch replacement, or cardio-pulmonary bypass with circulatory arrest were also excluded. Similar analytic algorithms have been previously used and validated to select type B dissections from administrative databases.12–14 Claims not included in the Medicare Denominator File were also excluded.

Patients were required to have at least 12 months of Medicare eligibility before surgery. Because Medicare is available only to patients once they are 65 years old, we excluded patients younger than 66 years old as this meant that they would not yet have received Medicare for a full 12 months. During the 12-month lead-in period, ICD-9 codes from 19 categories of patient comorbidities were used to construct patient-specific Charlson scores.14,15 The Charlson score is a comorbidity score that has been validated for use with administrative data sets and reflects the comorbidity profile of patients based on the ICD-9 codes their file contains.

Trends and outcomes

Changes in practice patterns for the treatment of type B dissection were analyzed in two ways. First, the numbers of TEVAR, OSR, and total repairs were analyzed on an annual basis with use of the total Medicare population as the denominator to determine rates of repair that were comparable across years. Next, the proportions of TEVAR and OSR per year were studied with total repairs as the denominator to determine the impact of each technique on total repairs annually.

Patient characteristics were analyzed among those undergoing TEVAR and OSR using data elements present in the Medicare database with specific attention to defined Charlson comorbidity categories. Our main outcome measures were in-hospital morbidity, perioperative mortality, and long-term mortality, determined at 3 years of follow-up. Although postoperative paraparesis and paraplegia are complications of interest in patients undergoing type B dissection repair, these are not coded reliably in the Medicare database and therefore could not be studied as an outcome.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographics were compared between groups by a Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical or dichotomous variables. Trends in procedure rates over time were compared by the Spearman test, whereas a nonparametric test for trend across ordered groups was used in comparing trends in patient comorbidities and perioperative mortality. In-hospital morbidity and perioperative mortality were binary categorical variables and were analyzed with χ2 tests.

Survival at 3 years was established with the Medicare Denominator File using specified date of death. Survival curves were estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis, and life-table analysis was used to establish rates of survival at 3 years with surrounding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Log-rank tests were used to determine significant differences in survival between groups. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed with use of Stata version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex).

RESULTS

Changes in use of OSR and TEVAR over time

Between 2000 and 2010, the overall rate of repair of type B dissection increased by 21%, from 2.5 to 3.0 per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries (P = .001; Fig 1). Concurrently, there was a decrease in the rate of OSR from 2.5 to 2.2 per 100,000 beneficiaries (P = .007) and a marked increase in the rate of TEVAR from 0 to 0.8 per 100,000 beneficiaries (P < .001). The most notable increase in TEVAR occurred after 2005 with the introduction of the TEVAR-specific ICD-9 procedural code (39.73; Supplementary Table, online only).

Fig 1.

Rates of type B aortic dissection repair in Medicare patients, 2000–2010, stratified by procedure type. CI, Confidence interval; TEVAR, thoracic endovascular aortic repair.

We next examined trends in procedure type by determining the proportion of all procedures that were TEVAR vs OSR on an annual basis. In 2000, OSR represented 99% of all type B dissection repairs, whereas TEVAR represented 1% (Fig 2). During the 10-year study period, TEVAR became more frequently performed such that by 2010, 27% of all type B dissection repairs were endovascular based, and the proportion of OSR had decreased to 73%.

Fig 2.

Proportion of open surgical repair (OSR) vs thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) in Medicare patients undergoing type B dissection repair, 2000–2010.

Patient characteristics and Charlson comorbidity profiles

Between 2000 and 2010, 11,159 patients underwent repair of type B dissection. Of these, 9470 patients underwent OSR (85%) and 1689 underwent TEVAR (15%) (Table). Patients undergoing TEVAR were older (75.8 years TEVAR, 74.5 years OSR; P < .001) and were less likely to be male (54% TEVAR, 56% OSR; P = .04) or white (82% TEVAR, 89% OSR; P < .001).

Table.

Demographics, comorbidities, and in-hospital complications for Medicare patients who underwent repair of type B thoracic aortic dissection, 2000–2010, with univariate analysis by open surgical repair (OSR) vs thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR)

| Variable | OSR | TEVAR | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 9470 | 1689 | |

| Age, yearsb | 74.5 (74.4–74.6) | 75.8 (75.5–76.1) | <.001 |

| Male | 5340 (56) | 906 (54) | .04 |

| White | 8381 (89) | 1391 (82) | <.001 |

| Charlson categories | |||

| History of myocardial infarction | 481 (5) | 109 (6) | .02 |

| Congestive heart failure | 860 (9) | 207 (12) | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1450 (15) | 573 (34) | <.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 288 (3) | 78 (5) | .001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 927 (10) | 285 (17) | <.001 |

| Dementia | 36 (0.4) | 16 (1) | .002 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 96 (1) | 23 (1) | .2 |

| Diabetes | 456 (5) | 140 (8) | <.001 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 16 (0.2) | 7 (0.4) | .04 |

| Chronic renal failure | 262 (3) | 140 (8) | <.001 |

| Cancer | 258 (3) | 63 (4) | .02 |

| Total Charlson score | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | <.001 |

| In-hospital complications | |||

| Death | 3757 (40) | 448 (27) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 1189 (13) | 152 (9) | <.001 |

| Bowel | 84 (1) | 19 (1) | .3 |

| Renal | 1549 (16) | 209 (12) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary | 4446 (47) | 531 (31) | <.001 |

| Length of stay, daysc | 15.7 (15.4–16.0) | 12.1 (11.5–12.8) | <.001 |

| Readmission within 30 days | 1833 (19) | 349 (21) | .2 |

| Readmission length of stay, daysc | 7.3 (6.9–7.7) | 6.6 (5.9–7.2) | .1 |

CI, Confidence interval.

Continuous data are presented as mean (95% CI) and categorical data as number (%).

P value from χ2 test for dichotomous variables.

P value from independent group t-test.

P value from independent group t-test.

TEVAR patients were also more likely to have a number of comorbid conditions. TEVAR patients had increased rates of prior myocardial infarction (6% vs 5%; P = .02), congestive heart failure (12% vs 9%; P < .001), peripheral vascular disease (34% vs 15%; P < .001), cerebrovascular disease (5% vs 3%; P = .001), chronic pulmonary disease (17% vs 10%; P < .001), dementia (1% vs 0.4%; P = .002), diabetes (8% vs 5%; P < .001), chronic renal failure (8% vs 3%; P < .001), and cancer (4% vs 3%; P = .02; Table). The mean Charlson score among TEVAR patients was 1.6 (95% CI, 1.5–1.7), significantly higher than the score of 0.9 (95% CI, 0.8–0.9) in the OSR group, representing an overall higher comorbidity burden in the endovascular group (P < .001).

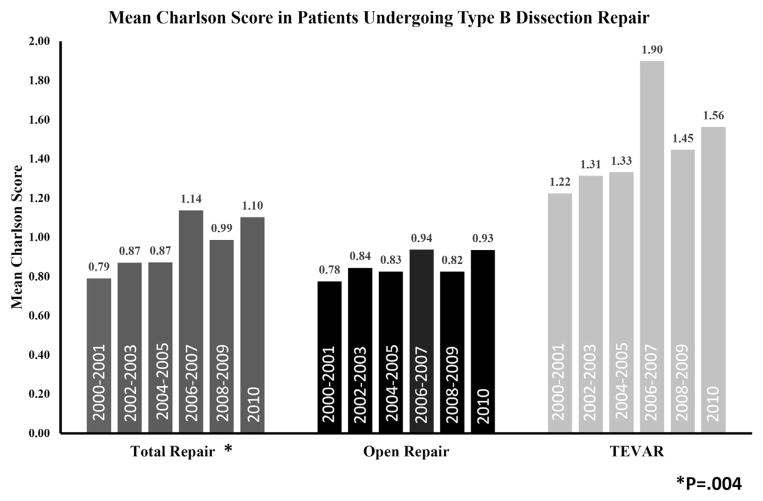

To determine how the comorbidity profile of patients undergoing repair has changed over time, the mean Charlson score was determined for each group in 2-year increments. The mean Charlson score for overall repairs was 0.79 at the beginning of the study period (2000–2001) and increased to 1.10 by 2010 (P = .04; Fig 3). When stratified by procedure type, OSR patients had a mean Charlson score of approximately 0.8 throughout the study period. By comparison, patients undergoing TEVAR had uniformly increased mean Charlson scores compared with OSR patients (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Mean Charlson comorbidity score of Medicare patients undergoing type B dissection repair in 2-year increments, 2000–2010, stratified by procedure type. TEVAR, Thoracic endovascular aortic repair.

In-hospital outcomes and perioperative mortality trends in TEVAR and OSR

When in-hospital outcomes were analyzed, OSR was associated with higher rates of perioperative stroke (13% vs 9%; P < .001), renal complications (16% vs 12%; P < .001), and pulmonary complications (47% vs 31%; P < .001) compared with TEVAR (Table). Mean length of stay was shorter in the TEVAR group at 12.1 days compared with 15.7 days in the OSR group (P < .001). OSR and TEVAR patients were equally likely to be readmitted (19% vs 21%; P = .2).

Of the 11,159 patients undergoing repair during the 10-year study period, perioperative death occurred in 4205 (38%). The perioperative mortality rate was 40% in the OSR group (3757 of 9470) compared with 27% in the TEVAR group (448 of 1689; P < .001).

However, when we examined trends in perioperative mortality, there was significant improvement in perioperative mortality rates over time (Fig 4). Mortality rates for overall repairs decreased significantly from 47% in 2000 to 23% in 2010 (P < .001). Significant decreases were also seen when annual perioperative mortality rates were stratified by procedure type. For OSR, perioperative mortality improved from 47% in 2000 to 25% in 2010 (P < .001); for TEVAR, perioperative mortality improved from 47% for the two combined years 2000 and 2001 (when only 58 procedures were performed) to 18% in 2010 (P < .001).

Fig 4.

Rates of perioperative mortality in Medicare patients undergoing type B aortic dissection repair, 2000–2010, stratified by procedure type. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) years 2000 and 2001 are condensed to a single time point because of low total numbers of TEVAR in those years.

Three-year survival by repair type and gender

Patients undergoing TEVAR had a 3-year survival rate of 61% (95% CI, 58.5–63.4), which was not significantly different from the open repair 3-year survival rate of 59.0% (95% CI, 58.0–60.0; P = .16). This was true despite the fact that TEVAR patients appeared to do better in the immediate postoperative period on the basis of the Kaplan-Meier curves (Fig 5).

Fig 5.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival in open surgical repair (OSR) vs thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) with life-table analysis showing 3-year survival (inset). P value from log-rank test. Total patients at risk for various time points are also shown (bottom).

Because of recent reports of potential gender-related disparities in survival and anatomic suitability for endovascular repair among patients with aortic dissection16 and abdominal aortic aneurysms,17,18 we further stratified survival at 3 years by gender and procedure type (Fig 6). We observed that women and men had similar 3-year survival after OSR (58.3% [95% CI, 56.8–59.8] in women vs 59.6% [95% CI, 58.2–60.9] in men; P = .29). However, there was a trend toward inferior 3-year survival among women undergoing TEVAR (59.3% [95% CI, 55.6–62.8] in women vs 62.4% [95% CI, 59.0–65.7] in men; P = .07).

Fig 6.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival in men vs women after open surgical repair (OSR; top) and thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR; bottom). P value from log-rank test. Three-year survival estimates, from life-table analysis (right).

DISCUSSION

The application and evolution of TEVAR have led to dramatic changes in the treatment of thoracic aortic disease. Previous studies have shown that TEVAR is now being applied for a variety of thoracic aortic diseases,12 and in the case of thoracic aortic aneurysm, adoption of TEVAR has led to an increase in the overall number of repairs performed nationwide.11 Our study demonstrates that more than one fourth of type B dissection repairs are now performed in an endovascular fashion and that the adoption of these techniques has led to an increase in the rate at which type B dissections are being repaired. Furthermore, patients treated with TEVAR appear to have significantly more comorbidities than do patients undergoing open repair. Despite these differences in patient characteristics, TEVAR patients have lower rates of in-hospital morbidity and mortality compared with OSR patients and comparable 3-year survival rates. Thus, TEVAR for type B dissection has expanded the group of patients being offered repair to include those with more comorbidities without incurring inferior outcomes.

Interestingly, we found that the adoption of TEVAR for type B dissection has coincided with a dramatic decrease in perioperative mortality rates for all patients undergoing repair, a phenomenon observed for both TEVAR and open repair groups. These changes have occurred, we believe, for two reasons: (1) improvements in patient selection and (2) a possible shift in the perceived threshold for repair of type B dissection. At the beginning of our study period, in 2000, nearly every patient was being treated with open repair, which was mostly reserved for patients with acute type B dissection complicated by impending rupture, organ malperfusion, intractable pain, uncontrollable hypertension, or rapid growth.1,19 For patients in the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD), open repair in this setting incurred a perioperative mortality rate of 29% to 34%,2,4 similar to the overall perioperative mortality rate, in 2000, of 47% reported here.

During the course of the study period, TEVAR was adopted, allowing the treatment of more comorbid patients; and as rates of TEVAR increased, the rates of overall repairs performed also increased by 21%. By 2010, patients who presented with clear-cut indications for repair of type B dissection could be considered for either TEVAR or OSR. Patients who may have not previously been offered open repair could now be treated with TEVAR. We believe that improved patient selection for both treatment modalities, based on patient comorbidity and dissection anatomy, contributed to improvement in perioperative mortality rates over time. These improvements in perioperative mortality for an acute aortic process are not without precedent as similar dramatic decreases in mortality were seen for both intact and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms after the introduction of endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR).20

Concurrently, some surgeons began advocating TEVAR for additional indications: uncomplicated subacute or chronic dissection to prevent future aneurysmal degeneration.1,9,19,21 As a result, it is likely that the acuity of presentation of type B dissections undergoing repair was “diluted” over time by selection of patients for repair who presented with uncomplicated subacute or chronic disease. This effect has probably also contributed to improvements in perioperative mortality. Unfortunately, our current data set does not allow us to determine the extent to which this has occurred. These efforts will require detailed clinical registries, such as the Vascular Quality Initiative’s national TEVAR data set, to examine if differences in patient selection and disease anatomy are driving the changes we have observed in our current analysis.

Trends in the adoption of TEVAR described here are likely to represent only the initial stages of even broader application of endovascular treatments for type B dissection. Although more than one fourth of type B dissections were being repaired by TEVAR in 2010, this proportion is likely to increase further. Population-based studies have shown that TEVAR is used for one third of thoracic aortic aneurysm repairs11 and that EVAR is applied in more than half of abdominal aortic aneurysm repairs.20,22 Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first endovascular device for acute and chronic type B dissection, a regulatory decision that will surely increase the availability and promotion of this technology. As a result, it is likely that more patients with type B dissection will be treated with TEVAR and that future device improvements will allow the treatment of more complex anatomic disease. Prospective, detailed clinical registries will also be essential in continuing to study the adoption of TEVAR for type B dissection as it becomes more widely applied.

Our findings are consistent with others showing that TEVAR patients tend to have more comorbidities than do patients undergoing OSR for acute type B dissection. A study of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2005 to 2007 showed that TEVAR patients had higher rates of renal failure, hypertension, history of myocardial infarction, and peripheral vascular disease, whereas rates of postoperative cardiac complications, respiratory complications, and acute renal failure were lower compared with patients undergoing open repair.13 We found that TEVAR patients were more likely to carry diagnoses of multiple comorbid diseases compared with OSR patients. Though useful in representing the overall chronic comorbidity burden, it should be stressed that the Charlson score does not offer a description of the patient’s acute presentation, such as dissection anatomy, presence of symptoms, and hemodynamic parameters. The overall increase in Charlson score observed from 2000 to 2010 suggests that patients with more chronic comorbidities are undergoing repair than previously, implying that the perception of TEVAR as a less invasive treatment option has expanded the patients deemed eligible for repair.

The 3-year survival rates reported here for TEVAR (62%) and OSR (59%) are lower than those recently reported by the IRAD (TEVAR, 76%; OSR, 83%),6 although they are consistent with 5-year survival rates reported from another study using Medicare data spanning a shorter time (TEVAR, 58%; OSR, 51%).12 These outcomes are likely to be slightly inferior to those reported in IRAD and randomized studies because they represent type B dissections repaired across multiple institutions, in a real-world setting, and only patients older than 65 years are included.

Gender also appears to potentially have an impact on prognosis in aortic dissection. IRAD investigators identified gender as a risk factor in all thoracic dissections, showing that surgical outcomes and long-term mortality were inferior among women compared with men treated for aortic dissection.6,16 Worse outcomes in women have also been seen with the use of endovascular techniques for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm. On the basis of blinded anatomic analyses, women are less likely than men to meet device-specific criteria for EVAR.17 Further, a retrospective review of the EUROSTAR database showed that women undergoing EVAR had higher complication and reintervention rates than men did.18 Our data imply a trend toward inferior outcomes in women undergoing endovascular repair of type B dissection compared with men, whereas no difference was seen in outcomes for open repair stratified by gender. These results suggest a potential impact of gender on surgical outcomes that justify further study of TEVAR for type B dissection.

Randomized controlled trials evaluating the use of TEVAR for type B dissection are clearly needed. Long-term results from the INSTEAD trial and results of the ADSORB trial23 will help determine the safety and efficacy of TEVAR in this setting. However, these data will likely be susceptible to multiple interpretations.24 Our results offer important insights into how new technology is adopted, even in the absence of randomized data supporting its use, and depict how type B dissections are repaired in more than 10,000 patients in a real-world setting.

Our study has several limitations. First, the data set contains no anatomic data. Although we are confident that we were able to isolate type B dissections by our coding algorithm, we cannot determine whether dissections involved visceral arteries or were associated with intramural hematomas/penetrating ulcers or frank rupture. These are important considerations, and changes in type B dissection anatomy may have occurred during the study period. Second, we are unable to determine the timing of intervention with regard to the onset of symptoms. During the study period, TEVAR emerged as a potential therapy to prevent aneurysmal degeneration of chronic dissection.8,9 Although the validity of this is still being studied, the practice of treating chronic dissection with TEVAR has presumably been adopted by some, and it is unclear how this has affected national practice patterns. Similarly, it is unknown if there have been any changes in dissection anatomy or timing of intervention in patients undergoing open repair, factors that may have contributed to improved perioperative mortality in this group. Third, there is sure to be heterogeneity in the devices used for TEVAR in this database, although we do not have any device-specific information, thus limiting our ability to determine how devices are being used. Furthermore, we have no information on chimney techniques, fenestrations, and other modalities that may be influencing the overall endovascular treatment of type B dissection.

Although our coding strategy has been previously validated,11,14 there is always the potential for coding errors and misclassifications in administrative data sets, and the extent to which this occurred cannot be known. Specifically, there may be a small number of type A dissection repairs included in this data set if they did not carry concomitant codes for valve replacement, coronary artery bypass graft, aortic arch replacement, or cardiopulmonary bypass with circulatory arrest, although we believe, on the basis of our prior validation of this algorithm, that misclassification occurs infrequently. Also, the TEVAR-specific ICD-9 code (39.73) was only introduced in 2005, midway through the study period. However, we believe that the pattern of use for the two codes representing TEVAR (39.73 and 39.79; Supplementary Table, online only) shows that we were able to accurately capture a transition period in the coding of type B dissection. As alluded to previously, many of these limitations will be addressed when our future work examines the reasons for underlying changes in practice patterns and outcomes with use of clinical data sets.

CONCLUSIONS

Rates of type B dissection repair have increased over time, which can be primarily attributed to the adoption of TEVAR. Patients treated with TEVAR have more comorbidities than do those treated with open repair, but despite this, perioperative mortality rates have improved dramatically among all patients undergoing type B dissection repair. The more prominent role of TEVAR appears to be justified, although additional work needs to be performed to define the patient population that will most benefit from endovascular treatment. Future efforts toward improving patient selection should specifically consider gender-based differences in open and endovascular outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

Presented at the Fortieth Annual Meeting of the New England Society for Vascular Surgery, Stowe, Vt, September 27–29, 2013.

Additional material for this article may be found online at www.jvascsurg.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: PG, BN, BB, MF, RP, DS

Analysis and interpretation: DJ, PG, DS

Data collection: PG, BN, DS

Writing the article: DJ, PG, DS

Critical revision of the article: DJ, PG, BN, BB, MF, RP, DS

Final approval of the article: DJ, PG, BN, BB, MF, RP, DS

Statistical analysis: DJ, PG, DS

Obtained funding: PG, DS

Overall responsibility: DS

References

- 1.Bastos Goncalves F, Metz R, Hendriks JM, Rouwet EV, Muhs BE, Poldermans D, et al. Decision-making in type-B dissection: current evidence and future perspectives. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2010;51:657–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trimarchi S, Nienaber CA, Rampoldi V, Myrmel T, Suzuki T, Bossone E, et al. Role and results of surgery in acute type B aortic dissection: insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) Circulation. 2006;114:I357–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozinovski J, Coselli JS. Outcomes and survival in surgical treatment of descending thoracic aorta with acute dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:965–70. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.11.013. discussion: 970–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fattori R, Tsai TT, Myrmel T, Evangelista A, Cooper JV, Trimarchi S, et al. Complicated acute type B dissection: is surgery still the best option? A report from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duson SM, Crawford RS. The role of endografts in the management of type B aortic dissections. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2012;24:177–83. doi: 10.1177/1531003513491983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai TT, Fattori R, Trimarchi S, Isselbacher E, Myrmel T, Evangelista A, et al. Long-term survival in patients presenting with type B acute aortic dissection: insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Circulation. 2006;114:2226–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.622340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leurs LJ, Bell R, Degrieck Y, Thomas S, Hobo R, Lundbom J, et al. Endovascular treatment of thoracic aortic diseases: combined experience from the EUROSTAR and United Kingdom Thoracic Endograft registries. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:670–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.07.008. discussion: 679–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nienaber CA, Rousseau H, Eggebrecht H, Kische S, Fattori R, Rehders TC, et al. Randomized comparison of strategies for type B aortic dissection: the INvestigation of STEnt Grafts in Aortic Dissection (INSTEAD) trial. Circulation. 2009;120:2519–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.886408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nienaber CA, Kische S, Rousseau H, Eggebrecht H, Rehders TC, Kundt G, et al. Endovascular repair of type B aortic dissection: long-term results of the randomized investigation of stent grafts in aortic dissection trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:407–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.113.000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scali ST, Feezor RJ, Chang CK, Stone DH, Hess PJ, Martin TD, et al. Efficacy of thoracic endovascular stent repair for chronic type B aortic dissection with aneurysmal degeneration. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:10–7. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.12.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scali ST, Goodney PP, Walsh DB, Travis LL, Nolan BW, Goodman DC, et al. National trends and regional variation of open and endovascular repair of thoracic and thoracoabdominal aneurysms in contemporary practice. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:1499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conrad MF, Ergul EA, Patel VI, Paruchuri V, Kwolek CJ, Cambria RP. Management of diseases of the descending thoracic aorta in the endovascular era: a Medicare population study. Ann Surg. 2010;252:603–10. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f4eaef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachs T, Pomposelli F, Hagberg R, Hamdan A, Wyers M, Giles K, et al. Open and endovascular repair of type B aortic dissection in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:860–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.05.008. discussion: 866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodney PP, Travis L, Lucas FL, Fillinger MF, Goodman DC, Cronenwett JL, et al. Survival after open versus endovascular thoracic aortic aneurysm repair in an observational study of the Medicare population. Circulation. 2011;124:2661–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.033944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nienaber CA, Fattori R, Mehta RH, Richartz BM, Evangelista A, Petzsch M, et al. Gender-related differences in acute aortic dissection. Circulation. 2004;109:3014–21. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130644.78677.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sweet MP, Fillinger MF, Morrison TM, Abel D. The influence of gender and aortic aneurysm size on eligibility for endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:931–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grootenboer N, Hunink MG, Hendriks JM, van Sambeek MR, Buth J EUROSTAR collaborators. Sex differences in 30-day and 5–year outcomes after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the EUROSTAR study. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:42–9. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svensson LG, Kouchoukos NT, Miller DC, Bavaria JE, Coselli JS, Curi MA, et al. Expert consensus document on the treatment of descending thoracic aortic disease using endovascular stent-grafts. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:S1–41. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.10.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giles KA, Pomposelli F, Hamdan A, Wyers M, Jhaveri A, Schermerhorn ML. Decrease in total aneurysm-related deaths in the era of endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.09.067. discussion: 550–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsa CJ, Williams JB, Bhattacharya SD, Wolfe WG, Daneshmand MA, McCann RL, et al. Midterm results with thoracic endovascular aortic repair for chronic type B aortic dissection with associated aneurysm. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:322–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarze ML, Shen Y, Hemmerich J, Dale W. Age-related trends in utilization and outcome of open and endovascular repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm in the United States, 2001–2006. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:722–9. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brunkwall J, Lammer J, Verhoeven E, Taylor P. ADSORB: a study on the efficacy of endovascular grafting in uncomplicated acute dissection of the descending aorta. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44:31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunkwall J, Lubke T, Power AH, Forbes TL. Debate: Whether level I evidence comparing thoracic endovascular repair and medical management is necessary for uncomplicated type B aortic dissections. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:836–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.