Abstract

Study Design

Randomized trial with a concurrent observational cohort study

Objective

To compare 8-year outcomes of surgery to non-operative care for symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis (SpS)

Summary of Background Data

Surgery for SpS has been shown to be more effective compared to non-operative treatment over four years, but longer-term data is less clear.

Methods

Surgical candidates from 13 centers in 11 U.S. states with at least 12 weeks of symptoms and confirmatory imaging were enrolled in a randomized cohort (RCT) or observational cohort (OBS). Treatment was standard decompressive laminectomy versus standard non-operative care. Primary outcomes were SF-36 bodily pain (BP) and physical function (PF) scales and the modified Oswestry Disability index (ODI) assessed at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and yearly up to 8 years.

Results

55% of RCT and 52% of OBS participants provided data at the 8-year follow-up. Intent-to-treat analyses showed no differences between randomized cohorts; however, 70% of those randomized to surgery and 52% of those randomized to non-operative had undergone surgery by 8 years. As-treated analyses in the RCT showed the early benefit for surgery out to 4 years converged over time with no significant treatment effect of surgery seen in years 6–8 for any of the primary outcomes. In contrast, the OBS group showed a stable advantage for surgery in all outcomes between years 5–8. Patients who were lost to follow-up were older, less well-educated, sicker, and had worse outcomes over the first 2 years in both surgery and non-operative arms.

Conclusions

Patients with symptomatic spinal stenosis show diminishing benefits of surgery in as-treated analyses of the RCT between 4–8 years while outcomes in the OBS group remained stable. Loss to follow-up of patients with worse early outcomes in both treatment groups could lead to overestimates of long-term outcomes, but likely not bias treatment effect estimates.

Keywords: Spinal stenosis, degenerative spondylolisthesis, randomized trial, surgery, non-operative, SPORT, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Lumbar spinal stenosis (SpS) is a common reason for spine surgery among older adults in the United States.1 Prior studies have found an advantage for surgery compared to non-operative treatment; however, these studies included a mixed group with and without degenerative spondylolisthesis.2–4 In prior reports from the SPORT study, as-treated comparisons with careful control for potentially confounding baseline factors showed that patients with SpS who were treated surgically had substantially greater improvement in pain and function out to 4 years than patients treated non-operatively.5,6 In this paper, we assess the stability of pain and functional outcomes out to eight years for patients with SpS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

SPORT was conducted in 11 states at 13 US medical centers with multidisciplinary spine practices. SPORT included both a randomized cohort (RCT) and a concurrent observational cohort (OBS) of patients who declined randomization but met all other inclusion exclusion criteria and were willing to be followed in the same manner as the randomized patients. 6–10 This design can allow for improved generalizability. 11

Patient Population

All patients had neurogenic claudication and/or radicular leg symptoms; confirmatory cross-sectional imaging showing lumbar spinal stenosis at one or more levels; and were judged to be surgical candidates. Patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis were analyzed in a separate cohort.8,12 All patients had ongoing symptoms for a minimum of 12 weeks which had not improved sufficiently with non-operative intervention. The content of pre-enrollment non-operative care was not pre-specified but included: physical therapy (68%); epidural injections (56% ); chiropractic (28% ); anti-inflammatories (55% ); and opioid analgesics (27% ). Enrollment began March 2000 and ended in March 2004.

Study Interventions

The protocol surgery consisted of a standard posterior decompressive laminectomy. 7 The non-operative protocol was “usual care” recommended to include at least: active physical therapy, education/counseling with home exercise instruction, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories if tolerated. 7,13 An extensive menu of additional treatment options (e.g. epidural steroids, analgesics, spinal manipulation, etc.) was tracked for all patients.

Study Measures

Primary endpoints were the SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) and Physical Function (PF) scales, 14–17 and the AAOS/Modems version of the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) 18 measured at six weeks, three months, six months, and yearly out to four years. If surgery was delayed beyond six weeks, additional follow-up data were obtained six weeks and three months post-operatively. Secondary outcomes included patient self-reported improvement; satisfaction with current symptoms and care;19 stenosis bothersomeness;2,20 and low back pain bothersomeness.2 Treatment effect was defined as the difference in the mean changes from baseline between the surgical and non-operative groups (difference of differences).

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating less severe symptoms; the Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms; the Stenosis Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms; and the Low Back Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

Statistical Considerations

Statistical methods for the analysis of this trial have been reported in previous publications,6,8–10,12,21 and these descriptions are repeated or paraphrased here as necessary. The randomized cohorts were initially analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis. Because of crossover, subsequent analyses were based on treatments actually received as described previously. 5,12

Primary analyses compared surgical and non-operative treatments using changes from baseline at each follow-up, with a mixed effects longitudinal regression model including a random individual effect to account for correlation between repeated measurements within individuals. In the as-treated analyses, the treatment indicator was a time-varying covariate, allowing for variable times of surgery. Follow-up times were measured from enrollment for the intent-to-treat analyses, whereas for the as-treated analysis the follow-up times were measured from the beginning of treatment (i.e. the time of surgery for the surgical group and the time of enrollment for the non-operative group), and baseline covariates were updated to the follow-up immediately preceding the time of surgery. This procedure has the effect of including all changes from baseline prior to surgery in the estimates of the non-operative treatment effect and all changes after surgery in the estimates of the surgical effect. The six-point sciatica scales and binary outcomes were analyzed via longitudinal models based on generalized estimating equations 22 with linear and logit link functions respectively, using the same intent-to-treat and adjusted as-treated analysis definitions as the primary outcomes. The randomized and observational cohorts were each analyzed to produce separate as-treated estimates of treatment effect. These results were compared using a Wald test to simultaneously test all follow-up visit times for differences in estimated treatment effects between the two cohorts.23

To evaluate the two treatment arms across all time-periods, the time-weighted average of the outcomes (area under the curve) for each treatment group was computed using the estimates at each time period from the longitudinal regression models and compared using a Wald test. 23 Kaplan-Meier estimates of re-operation rates at 8 years were computed for the randomized and observational cohorts and compared via the log-rank test. 24,25

Computations were done using SAS procedures PROC MIXED for continuous data and PROC GENMOD for binary and non-normal secondary outcomes (SAS version 9.1 Windows XP Pro, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 based on a two-sided hypothesis test with no adjustments made for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

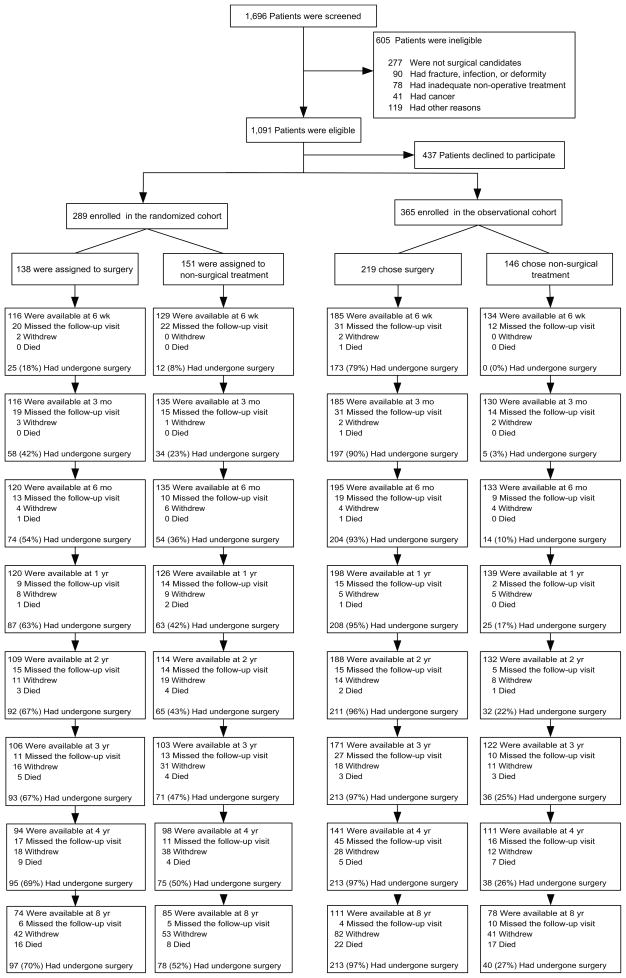

A total of 654 SpS participants were enrolled out of 1,091 eligible for enrollment (289 in the RCT and 365 in the OBS) (Figure 1). In the RCT, 138 were assigned to surgical treatment and 151 to non-operative treatment. Of those randomized to surgery, 67% [92/138] received surgery by 2 years, 69% [95/138] by 4 years, and 70% [97/138] by 8 years. In the group randomized to non-operative care, 43% [65/151] received surgery by 2 years, 49% [75/151] by 4 years, and 52% [78/151] by 8 years (Figure 1). In the OBS group, 219 patients initially chose surgery and 146 patients initially chose non-operative care. Of those initially choosing surgery, 96% [211/219] received surgery by 2 years, and 97% [213/219] by 4 years; this remained unchanged at 8 years. Of those choosing non-operative treatment, 22% [32/146] had surgery by 2 years, 26% [38/146] by 4 years, and 27% [40/146] by 8 years (Figure 1). The proportion of enrollees who supplied data at the 8-year follow-up visit was 55% in the RC and 52% in the OC with losses due to dropouts, missed visits, or deaths.

Figure 1.

Exclusion, Enrollment, Randomization and Follow-up of SpS Trial Participants The values for surgery, withdrawal, and death are cumulative over four years. For example, a total of 16 patients in the group assigned to surgery died during the 8-year follow-up period.

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 shows the summary statistics of participants in the RCT and OBS cohorts and according to treatment received. The randomized and observational cohorts were remarkably similar except for their preferences for surgery (p < 0.001), with more RCT patients unsure of their preference (34% vs. 7%), and fewer RCT patients definitely preferring either surgery (12% vs. 46%) or non-operative treatment (13% vs. 24%).

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures according to study cohort and treatment received.

| SPORT Study Cohort | Randomized and Observational Cohorts Combined: Treatment Received* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPS | Randomized (n=278) | Observational (n=356) | p-value | Surgery (n=422) | Non-Operative (n=212) | p-value |

| Mean Age (SD) | 65.5 (10.5) | 63.9 (12.5) | 0.10 | 63.9 (12.1) | 66.1 (10.6) | 0.022 |

| Female - no. (%) | 106 (38%) | 143 (40%) | 0.66 | 162 (38%) | 87 (41%) | 0.58 |

| Ethnicity: Not Hispanic - no. (%)† | 259 (93%) | 346 (97%) | 0.027 | 405 (96%) | 200 (94%) | 0.47 |

| Race - White - no. (%) | 238 (86%) | 295 (83%) | 0.41 | 355 (84%) | 178 (84%) | 0.95 |

| Education - At least some college - no. (%) | 176 (63%) | 225 (63%) | 0.96 | 265 (63%) | 136 (64%) | 0.81 |

| Marital Status - Married - no. (%) | 197 (71%) | 249 (70%) | 0.87 | 306 (73%) | 140 (66%) | 0.11 |

| Work Status - no. (%) | 0.12 | 0.42 | ||||

| Full or part time | 88 (32%) | 128 (36%) | 149 (35%) | 67 (32%) | ||

| Disabled | 24 (9%) | 36 (10%) | 40 (9%) | 20 (9%) | ||

| Retired | 144 (52%) | 152 (43%) | 188 (45%) | 108 (51%) | ||

| Other | 22 (8%) | 40 (11%) | 45 (11%) | 17 (8%) | ||

| Compensation - Any - no. (%)‡ | 21 (8%) | 27 (8%) | 0.89 | 30 (7%) | 18 (8%) | 0.64 |

| Mean Body Mass Index (BMI), (SD)§ | 29.8 (5.6) | 29.3 (5.6) | 0.31 | 29.4 (5.3) | 29.8 (6.2) | 0.44 |

| Smoker - no. (%) | 34 (12%) | 28 (8%) | 0.089 | 38 (9%) | 24 (11%) | 0.43 |

| Comorbidities - no. (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 134 (48%) | 154 (43%) | 0.25 | 182 (43%) | 106 (50%) | 0.12 |

| Diabetes | 50 (18%) | 46 (13%) | 0.098 | 58 (14%) | 38 (18%) | 0.20 |

| Osteoporosis | 22 (8%) | 38 (11%) | 0.30 | 32 (8%) | 28 (13%) | 0.032 |

| Heart Problem | 80 (29%) | 85 (24%) | 0.19 | 103 (24%) | 62 (29%) | 0.22 |

| Stomach Problem | 60 (22%) | 79 (22%) | 0.93 | 87 (21%) | 52 (25%) | 0.31 |

| Bowel or Intestinal Problem | 36 (13%) | 50 (14%) | 0.78 | 50 (12%) | 36 (17%) | 0.097 |

| Depression | 36 (13%) | 34 (10%) | 0.22 | 47 (11%) | 23 (11%) | 0.98 |

| Joint Problem | 158 (57%) | 188 (53%) | 0.35 | 227 (54%) | 119 (56%) | 0.64 |

| Other¶ | 95 (34%) | 125 (35%) | 0.87 | 145 (34%) | 75 (35%) | 0.87 |

| Time since most recent episode > 6 months | 158 (57%) | 210 (59%) | 0.64 | 251 (59%) | 117 (55%) | 0.34 |

| Bodily Pain (BP) Score (SD)|| | 33.7 (19.8) | 33.2 (19.7) | 0.75 | 30.9 (18.9) | 38.5 (20.3) | <0.001 |

| Physical Functioning (PF) Score (SD) | 35.4 (22.6) | 34.3 (23.8) | 0.55 | 32 (22.1) | 40.3 (24.5) | <0.001 |

| Mental Component Summary (MCS) Score (SD) | 49.7 (12.3) | 49 (11.6) | 0.47 | 48.6 (12) | 50.7 (11.6) | 0.037 |

| Oswestry (ODI) (SD)** | 42.7 (17.9) | 42.1 (19) | 0.70 | 45.3 (18) | 36.5 (18.1) | <0.001 |

| Stenosis Frequency Index (0–24) (SD)†† | 13.5 (5.7) | 14.2 (5.8) | 0.13 | 14.9 (5.6) | 11.8 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Stenosis Bothersome Index (0–24) (SD)‡‡ | 13.9 (5.7) | 14.7 (5.8) | 0.084 | 15.4 (5.4) | 12.3 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Back Pain Bothersomeness (SD)§§ | 4 (1.9) | 4.2 (1.8) | 0.19 | 4.2 (1.8) | 3.8 (1.8) | 0.014 |

| Leg Pain Bothersomeness (SD)¶¶ | 4.3 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.7) | 0.44 | 4.5 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with symptoms - very dissatisfied | 183 (66%) | 250 (70%) | 0.27 | 323 (77%) | 110 (52%) | <0.001 |

| Problem getting better or worse | 0.48 | <0.001 | ||||

| Getting better | 18 (6%) | 28 (8%) | 15 (4%) | 31 (15%) | ||

| Staying about the same | 95 (34%) | 108 (30%) | 118 (28%) | 85 (40%) | ||

| Getting worse | 160 (58%) | 218 (61%) | 282 (67%) | 96 (45%) | ||

| Treatment preference | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Definitely prefer non-surg | 37 (13%) | 86 (24%) | 42 (10%) | 81 (38%) | ||

| Probably prefer non-surg | 61 (22%) | 45 (13%) | 45 (11%) | 61 (29%) | ||

| Not sure | 95 (34%) | 26 (7%) | 69 (16%) | 52 (25%) | ||

| Probably prefer surgery | 51 (18%) | 36 (10%) | 76 (18%) | 11 (5%) | ||

| Definitely prefer surgery | 33 (12%) | 163 (46%) | 190 (45%) | 6 (3%) | ||

| Pseudoclaudication - Any - no. (%) | 219 (79%) | 289 (81%) | 0.51 | 341 (81%) | 167 (79%) | 0.62 |

| SLR or Femoral Tension | 41 (15%) | 91 (26%) | 0.001 | 89 (21%) | 43 (20%) | 0.89 |

| Pain radiation - any | 215 (77%) | 284 (80%) | 0.52 | 329 (78%) | 170 (80%) | 0.59 |

| Any Neurological Deficit | 146 (53%) | 203 (57%) | 0.29 | 228 (54%) | 121 (57%) | 0.52 |

| Reflexes - Asymmetric Depressed | 76 (27%) | 92 (26%) | 0.74 | 109 (26%) | 59 (28%) | 0.66 |

| Sensory - Asymmetric Decrease | 68 (24%) | 114 (32%) | 0.046 | 127 (30%) | 55 (26%) | 0.32 |

| Motor - Asymmetric Weakness | 71 (26%) | 106 (30%) | 0.28 | 110 (26%) | 67 (32%) | 0.17 |

| Stenosis Levels | ||||||

| L2-L3 | 77 (28%) | 102 (29%) | 0.86 | 128 (30%) | 51 (24%) | 0.12 |

| L3-L4 | 183 (66%) | 237 (67%) | 0.91 | 286 (68%) | 134 (63%) | 0.29 |

| L4-L5 | 255 (92%) | 324 (91%) | 0.86 | 389 (92%) | 190 (90%) | 0.35 |

| L5-S1 | 72 (26%) | 101 (28%) | 0.55 | 109 (26%) | 64 (30%) | 0.29 |

| Stenotic Levels (Mod/Severe) | 0.45 | 0.066 | ||||

| None | 4 (1%) | 11 (3%) | 6 (1%) | 9 (4%) | ||

| One | 106 (38%) | 128 (36%) | 149 (35%) | 85 (40%) | ||

| Two | 109 (39%) | 132 (37%) | 165 (39%) | 76 (36%) | ||

| Three+ | 59 (21%) | 85 (24%) | 102 (24%) | 42 (20%) | ||

| Stenosis Locations | ||||||

| Central | 241 (87%) | 302 (85%) | 0.58 | 365 (86%) | 178 (84%) | 0.46 |

| Lateral Recess | 236 (85%) | 267 (75%) | 0.003 | 343 (81%) | 160 (75%) | 0.11 |

| Neuroforamen | 88 (32%) | 119 (33%) | 0.70 | 127 (30%) | 80 (38%) | 0.065 |

| Stenosis Severity | 0.24 | <0.001 | ||||

| Mild | 4 (1%) | 11 (3%) | 6 (1%) | 9 (4%) | ||

| Moderate | 131 (47%) | 151 (42%) | 172 (41%) | 110 (52%) | ||

| Severe | 143 (51%) | 194 (54%) | 244 (58%) | 93 (44%) | ||

Patients in the two cohorts combined were classified according to whether they received surgical treatment or only nonsurgical treatment during the first 8 years of enrollment.

Race or ethnic group was self-assessed. Whites and blacks could be either Hispanic or non-Hispanic.

This category includes patients who were receiving or had applications pending for workers compensation, Social Security compensation, or other compensation.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Other = problems related to stroke, cancer, fibromyalgia, CFS, PTSD, alcohol, drug dependency, lung, liver, kidney, blood vessel, nervous system, migraine or anxiety.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Frequency Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Low Back Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms

The Leg Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

At baseline, patients in the group undergoing surgery within 8 years were younger and had slightly more osteoporosis than those receiving non-operative treatment. They had worse pain, function, disability, and symptoms than patients in the non-operative group. Patients in the surgery group were more dissatisfied with their symptoms and at enrollment more often rated their symptoms as worsening and definitely preferred surgery. These observations highlight the need to control for baseline differences in the as-treated models. Based on the selection procedure for variables associated with treatment, missing data and outcomes, the final as-treated models controlled for the following covariates: age; gender; compensation; baseline stenosis bothersomeness; income; smoking status; duration of most recent episode; treatment preference; diabetes; joint problem; stomach comorbidity; baseline score (for SF-36, ODI); and center.

Non-Operative Treatments

In the combined RCT/OBS, non-operative treatments included physical therapy (46%); visits to a surgeon (49%); nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (52%); and opioids (40%); More patients in the randomized cohort reported receiving injections (54% vs. 41%, p=0.017) while more observational patients reported receiving NSAIDS (59% vs. 47%, p=0.035) and “Other” medications (76% vs. 63%, p=0.01).

Surgical Treatment and Complications

For the combined cohorts, the mean surgical time was 129 minutes, with a mean blood loss of 311 ml (Table 2). The most common surgical complication remained dural tear (9%). The 8-year reoperation rate was 18%, with no significant difference between the RCT and OBS.

Table 2.

Operative treatments, complications and events

| SPS | Randomized Cohort (n=171)* | Observational Cohort (n=246)* | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | 0.53 | ||

| Decompression only | 143 (88%) | 215 (88%) | |

| Non-instrumented fusion | 7 (4%) | 15 (6%) | |

| Instrumented fusion | 12 (7%) | 13 (5%) | |

| Multi-level fusion | 5 (3%) | 12 (5%) | 0.46 |

| LaminectomyLevel | |||

| L2-L3 | 58 (35%) | 91 (38%) | 0.62 |

| L3-L4 | 126 (75%) | 160 (66%) | 0.056 |

| L4-L5 | 154 (92%) | 225 (93%) | 0.92 |

| L5-S1 | 65 (39%) | 92 (38%) | 0.93 |

| Levels decompresssed | 0.81 | ||

| 0 | 4 (2%) | 4 (2%) | |

| 1 | 36 (21%) | 58 (24%) | |

| 2 | 51 (30%) | 78 (32%) | |

| 3+ | 80 (47%) | 106 (43%) | |

| Operation time, minutes (SD) | 129.5 (64.2) | 128.6 (67) | 0.90 |

| Blood loss, cc (SD) | 332 (510.1) | 297 (310.3) | 0.39 |

| Blood Replacement | |||

| Intraoperative replacement | 16 (10%) | 24 (10%) | 0.91 |

| Post-operative transfusion | 8 (5%) | 13 (5%) | 1 |

| Length of hospital stay, days (SD) | 3.5 (2.6) | 3 (2.2) | 0.021 |

| Post-operative mortality (death within 6 weeks of surgery) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.85 |

| Post-operative mortality (death within 3 months of surgery) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.85 |

| Intraoperative complications§ | |||

| Dural tear/ spinal fluid leak | 15 (9%) | 23 (9%) | 0.98 |

| Other | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0.89 |

| None | 153 (90%) | 220 (90%) | 0.92 |

| Postoperative complications/events¶ | |||

| Wound hematoma | 3 (2%) | 1 (0%) | 0.37 |

| Wound infection | 4 (2%) | 5 (2%) | 0.92 |

| Other | 10 (6%) | 14 (6%) | 0.92 |

| None | 145 (87%) | 214 (87%) | 1 |

| Additional surgeries (1-year rate)|| | 7 (4%) | 14 (6%) | 0.46 |

| Additional surgeries (2-year rate)|| | 11 (6%) | 21 (8%) | 0.43 |

| Additional surgeries (3-year rate)|| | 16 (9%) | 29 (11%) | 0.43 |

| Additional surgeries (4-year rate)|| | 22 (13%) | 32 (13%) | 0.94 |

| Additional surgeries (5-year rate)|| | 26 (15%) | 33 (13%) | 0.66 |

| Additional surgeries (6-year rate)|| | 28 (16%) | 37 (15%) | 0.75 |

| Additional surgeries (7-year rate)|| | 30 (17%) | 41 (16%) | 0.83 |

| Additional surgeries (8-year rate)|| | 33 (19%) | 44 (17%) | 0.71 |

| Recurrent stenosis/progressive spondylolisthesis | 24 (15%) | 16 (7%) | |

| Pseudoarthrosis/fusion exploration | 0 | 1 (NE)** | |

| Complication or Other | 6 (4%) | 13 (5%) | |

| New condition | 3 (2%) | 9 (4%) | |

175 RCT and 253 OBS patients had surgery; surgical information was available for 171 RCT patients and 246 observational patients. Specific procedure information was available on 162 RCT and 243 OBS patients.

Patient died 9 days after surgery of a myocardial infarction. The death was judged probably related to treatment by the DHMC review and not related to treatment by the external review.

None of the following were reported: aspiration, nerve root injury, operation at wrong level, vascular injury.

Any reported complications up to 8 weeks post operation. None of the following were reported: bone graft complication, cerebrospinal fluid leak, nerve root injury, paralysis, cauda equina injury, wound dehiscence, pseudarthrosis.

One-, two-, three-four-, five-, six-, seven-, and eight-year post-surgical re-operation rates are Kaplan Meier estimates and p-values are based on the log-rank test. Numbers and percentages are based on the first additional surgery if more than one additional surgery. Surgeries include any additional spine surgery not just re-operation at the same level.

Not estimable

Mortality

At 8 years, there were 27 deaths in the non-operative group compared to 35 expected based on age-gender specific mortality rates; there were 39 deaths in the surgery group compared to 53 expected. The hazard ratio based on a proportional hazards model adjusted for age was 0.26 (95% CI: 0.45, 1.2; p=0.26). All 66 deaths were independently reviewed and 45 were judged not to be treatment-related. 1 patient died 9 days after surgery of a myocardial infarction. The death was judged probably related to treatment by the DHMC review and not related to treatment by the external review. Twenty deaths were from “unknown” causes with median (min, max) days from enrollment/surgery of 2297 (501, 2856).

Main Treatment effects

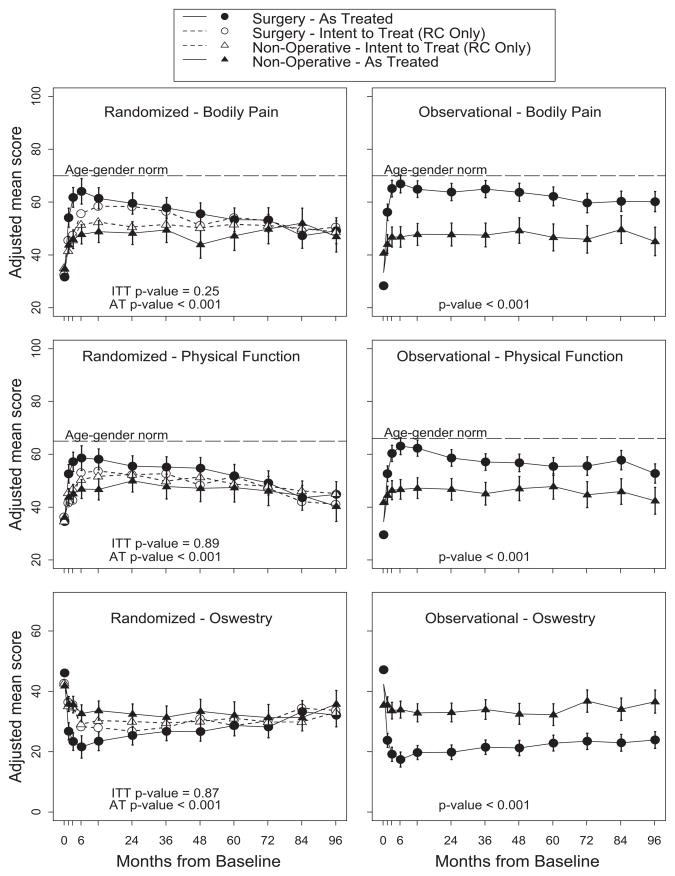

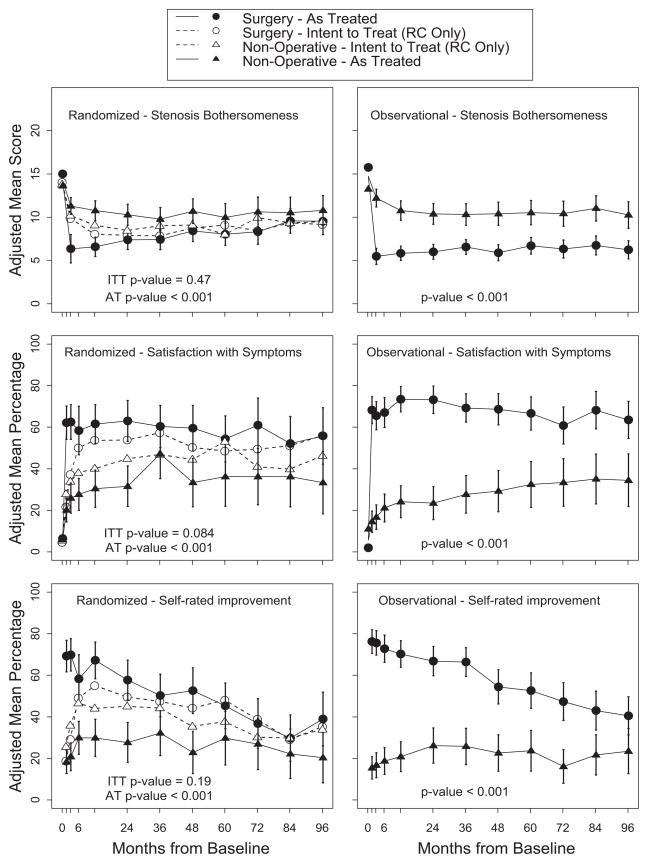

The intent-to-treat analyses of the SpS randomized cohort showed no statistical differences between surgery and non-operative care based on overall global hypothesis tests for differences in mean changes from baseline for either the primary (Figure 2) or secondary outcomes (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Intent-To-Treat vs. As-Treated Analyses for SF-36 Bodily Pain, SF-36 Physical Function, and the Oswestry Disability Index

Figure 3.

Intent-To-Treat and As-Treated Analyses for Stenosis Bothersomeness, Satisfaction with Symptoms, and Self-rated Improvement

In the as-treated analyses of the RCT, the advantage for surgery seen at 4 years diminished over time to the point that there were no longer any discernable differences between the treatment groups after 5 years, although the overall comparison between treatment groups remained significant (Figure 2). Interestingly, the advantage for surgery was maintained out to 8-years in the OBS cohort. The Wald test comparing the as-treated RCT and OBS treatment effects over all time periods was statistically significant only for ODI and of borderline significance for BP (p = 0.08 for BP; p = 0.36 for PF; and p= 0.02 for ODI).

Among the secondary outcomes, differences seen in the as-treated groups at 4 years were generally maintained at 8 years, however there was a steady decline over time in the proportion of surgery patients rating their result as a “major improvement” compared to baseline; this occurred in the OBS cohort as well despite relatively stable results on symptom severity and functional status measures in this cohort over the same time period.

Loss-to-Follow-up

At the 8-year follow-up, 53% of initial enrollees supplied data, with losses due to dropouts, missed visits, or deaths. Table 3 summarizes the baseline characteristics of those lost to follow-up compared to those retained in the study at 8 years. Those who remained in the study at 8 years were: somewhat younger; more likely to be college educated, married, and working at baseline; had fewer comorbidities; had a shorter duration of symptoms, less severe symptoms, and less severe radiographic stenosis at baseline. These differences were small but statistically significant. Table 4 summarizes the short-term outcomes during the first 2 years for those retained in the study at 8 years compared to those lost to follow-up. Those lost to follow-up had worse outcomes on average; however, this was true in both the surgical and non-operative groups with non-significant differences in treatment effects. The long-term outcomes are therefore likely to be somewhat over-optimistic on average in both groups, but the comparison between surgical and non-operative outcomes appear likely to be un-biased despite the long-term loss to follow-up.

Table 3.

Patient baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures according to patient follow-up status as of 09/03/2013 when the SPS 8yr data were pulled

| SPS | Patients currently in study (n=306) | Patients lost to follow-up (n=328) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 61.1 (10.4) | 67.9 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Female - no. (%) | 113 (37%) | 136 (41%) | 0.28 |

| Ethnicity: Not Hispanic - no. (%)† | 294 (96%) | 311 (95%) | 0.57 |

| Race - White - no. (%) | 262 (86%) | 271 (83%) | 0.36 |

| Education - At least some college - no. (%) | 217 (71%) | 184 (56%) | <0.001 |

| Marital Status - Married - no. (%) | 235 (77%) | 211 (64%) | <0.001 |

| Work Status - no. (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Full or part time | 142 (46%) | 74 (23%) | |

| Disabled | 28 (9%) | 32 (10%) | |

| Retired | 113 (37%) | 183 (56%) | |

| Other | 23 (8%) | 39 (12%) | |

| Compensation - Any - no. (%)‡ | 25 (8%) | 23 (7%) | 0.69 |

| Mean Body Mass Index (BMI), (SD)§ | 29.7 (5.7) | 29.3 (5.5) | 0.33 |

| Smoker - no. (%) | 23 (8%) | 39 (12%) | 0.086 |

| Comorbidities - no. (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 137 (45%) | 151 (46%) | 0.81 |

| Diabetes | 38 (12%) | 58 (18%) | 0.082 |

| Osteoporosis | 19 (6%) | 41 (12%) | 0.01 |

| Heart Problem | 60 (20%) | 105 (32%) | <0.001 |

| Stomach Problem | 63 (21%) | 76 (23%) | 0.49 |

| Bowel or Intestinal Problem | 34 (11%) | 52 (16%) | 0.10 |

| Depression | 43 (14%) | 27 (8%) | 0.027 |

| Joint Problem | 156 (51%) | 190 (58%) | 0.094 |

| Other¶ | 91 (30%) | 129 (39%) | 0.014 |

| Time since most recent episode > 6 months | 162 (53%) | 206 (63%) | 0.015 |

| Bodily Pain (BP) Score (SD)|| | 35.3 (19.8) | 31.8 (19.5) | 0.025 |

| Physical Functioning (PF) Score (SD) | 38.6 (23.4) | 31.3 (22.6) | <0.001 |

| Mental Component Summary (MCS) Score (SD) | 49.5 (11.9) | 49.2 (11.9) | 0.78 |

| Oswestry (ODI) (SD)** | 40.4 (17.5) | 44.2 (19.3) | 0.01 |

| Stenosis Frequency Index (0–24) (SD)†† | 13.9 (5.6) | 13.9 (5.9) | 0.95 |

| Stenosis Bothersome Index (0–24) (SD)‡‡ | 14.5 (5.4) | 14.2 (6) | 0.63 |

| Back Pain Bothersomeness (SD)§§ | 4.1 (1.8) | 4.1 (1.8) | 0.90 |

| Leg Pain Bothersomeness (SD)¶¶ | 4.4 (1.6) | 4.2 (1.8) | 0.23 |

| Satisfaction with symptoms - very dissatisfied | 204 (67%) | 229 (70%) | 0.44 |

| Problem getting better or worse | 0.95 | ||

| Getting better | 22 (7%) | 24 (7%) | |

| Staying about the same | 100 (33%) | 103 (31%) | |

| Getting worse | 181 (59%) | 197 (60%) | |

| Treatment preference | 0.21 | ||

| Definitely prefer non-surg | 64 (21%) | 59 (18%) | |

| Probably prefer non-surg | 45 (15%) | 61 (19%) | |

| Not sure | 67 (22%) | 54 (16%) | |

| Probably prefer surgery | 43 (14%) | 44 (13%) | |

| Definitely prefer surgery | 87 (28%) | 109 (33%) | |

| Pseudoclaudication - Any - no. (%) | 244 (80%) | 264 (80%) | 0.89 |

| SLR or Femoral Tension | 68 (22%) | 64 (20%) | 0.46 |

| Pain radiation - any | 245 (80%) | 254 (77%) | 0.48 |

| Any Neurological Deficit | 167 (55%) | 182 (55%) | 0.88 |

| Reflexes - Asymmetric Depressed | 69 (23%) | 99 (30%) | 0.037 |

| Sensory - Asymmetric Decrease | 101 (33%) | 81 (25%) | 0.026 |

| Motor - Asymmetric Weakness | 90 (29%) | 87 (27%) | 0.47 |

| Stenosis Levels | |||

| L2-L3 | 71 (23%) | 108 (33%) | 0.009 |

| L3-L4 | 183 (60%) | 237 (72%) | 0.001 |

| L4-L5 | 282 (92%) | 297 (91%) | 0.56 |

| L5-S1 | 86 (28%) | 87 (27%) | 0.72 |

| Stenotic Levels (Mod/Severe) | 0.10 | ||

| None | 5 (2%) | 10 (3%) | |

| One | 127 (42%) | 107 (33%) | |

| Two | 109 (36%) | 132 (40%) | |

| Three+ | 65 (21%) | 79 (24%) | |

| Stenosis Locations | |||

| Central | 251 (82%) | 292 (89%) | 0.016 |

| Lateral Recess | 243 (79%) | 260 (79%) | 0.96 |

| Neuroforamen | 110 (36%) | 97 (30%) | 0.10 |

| Stenosis Severity | 0.003 | ||

| Mild | 5 (2%) | 10 (3%) | |

| Moderate | 157 (51%) | 125 (38%) | |

| Severe | 144 (47%) | 193 (59%) |

Race or ethnic group was self-assessed. Whites and blacks could be either Hispanic or non-Hispanic.

This category includes patients who were receiving or had applications pending for workers compensation, Social Security compensation, or other compensation.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Other = problems related to stroke, cancer, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, alcohol, drug dependency, lung, liver, kidney, blood vessel, nervous system, migraine or anxiety.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Frequency Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Low Back Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms

The Leg Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

Table 4.

Adjusted* As-treated Change Scores and Treatment Effects for Primary Outcomes in the Randomized and Observational Cohorts Combined, According to Treatment Received and Patient Follow-up Status.

| Outcome | 3-Month | 1-Year | 2-Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| SPS | Patient follow-up status | Surgical | Non-operative | Treatment Effect† (95% CI) | Surgical | Non-operative | Treatment Effect† (95% CI) | Surgical | Non-operative | Treatment Effect† (95% CI) |

| SF-36 Bodily Pain (BP) (SE)†† | Currently in study | 31 (1.6) | 14.3 (1.8) | 16.7 (12.5, 21) | 32.3 (1.7) | 21.2 (2.1) | 11.1 (6.1, 16.1) | 31.1 (1.7) | 19.8 (2.2) | 11.3 (6.3, 16.3) |

| Lost to follow-up | 28.1 (1.7) | 12.4 (1.8) | 15.8 (11.3, 20.3) | 25.7 (1.8) | 9.4 (2) | 16.3 (11.3, 21.3) | 23.8 (1.9) | 10.1 (2.2) | 13.7 (8.3, 19.1) | |

|

| ||||||||||

| p-value | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0.76 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.50 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| SF-36 Physical Function (PF) (SE)†† | Currently in study | 26 (1.6) | 12.4 (1.8) | 13.6 (9.6, 17.5) | 30.9 (1.7) | 15.2 (2) | 15.7 (11.1, 20.4) | 26.6 (1.6) | 17.9 (2.1) | 8.8 (4.1, 13.4) |

| Lost to follow-up | 20.6 (1.7) | 9.5 (1.8) | 11.1 (6.9, 15.3) | 18 (1.7) | 8.8 (1.9) | 9.2 (4.6, 13.9) | 15.4 (1.8) | 8.8 (2.1) | 6.6 (1.6, 11.6) | |

|

| ||||||||||

| p-value | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.38 | <0.001 | 0.023 | 0.048 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.52 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (SE) )‡ | Currently in study | −23.2 (1.3) | −10.2 (1.4) | −13 (−16.2, −9.8) | −24.6 (1.3) | −11.7 (1.6) | −13 (−16.7, −9.2) | −23.2 (1.3) | −13 (1.7) | −10.1 (−13.9, −6.4) |

| Lost to follow-up | −19.2 (1.3) | −5.9 (1.4) | −13.3 (−16.7, −9.9) | −16.3 (1.4) | −7 (1.5) | −9.3 (−13.1, −5.5) | −16.5 (1.4) | −6.3 (1.7) | −10.2 (−14.3, −6.2) | |

|

| ||||||||||

| p-value | 0.028 | 0.029 | 0.90 | <0.001 | 0.037 | 0.17 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.97 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Stenosis Bothersomeness Index (SE)§ | Currently in study | −8.5 (0.6) | −3 (0.5) | −5.5 (−7, −4.1) | −8.6 (0.5) | −4.8 (0.6) | −3.8 (−5.2, −2.4) | −8 (0.5) | −4.9 (0.6) | −3.1 (−4.5, −1.7) |

| Lost to follow-up | −8.3 (0.6) | −2.9 (0.5) | −5.4 (−6.9, −3.9) | −7.3 (0.5) | −3 (0.6) | −4.3 (−5.7, −2.9) | −7.1 (0.5) | −3.9 (0.6) | −3.1 (−4.7, −1.6) | |

|

| ||||||||||

| p-value | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.066 | 0.024 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.93 | |

Adjusted for age, gender, compensation, baseline score of stenosis bothersomeness index, income, smoking status, duration of most recent episode, treatment preference, diabetes, joint problem, stomach comorbidity, baseline score (for SF-36 and ODI), and center.

Treatment effect is the difference between the surgical and non-operative mean change from baseline.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Bothersomeness index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

DISCUSSION

In patients presenting with signs and symptoms of image confirmed SpS persisting for at least twelve weeks, the intention-to-treat analysis found no significant difference between surgical or non-operative treatment. However, as has been reported previously, these results must be viewed in the context of substantial rates of non-adherence to the assigned treatment; this mixing of treatments generally biases treatment effect estimates towards the null,6–10,12,21

As-treated analyses continue to show an overall advantage for surgery; however, in the RCT, the as-treated results for surgery and non-operative treatment converged after 5 years. The advantage for surgery in the OBS group at 4 years was maintained out to 8-years. This is the only divergence in outcomes seen so far between the RCT and OBS results. This may have to do with greater baseline differences in the OBS groups than the RCT as-treated groups. Although the as-treated analysis of the RCT loses the strong protection against confounding supplied by randomization, the RCT as-treated groups were much more similar at baseline than the OBS groups. Thus the long-term results in the as-treated RCT are somewhat less likely to be confounded by baseline differences, suggesting that the advantage of surgery in SpS likely does diminish over time.

Comparisons to Other Studies

SPORT represents by far the largest study of its kind, and the largest study to isolate spinal stenosis from stenosis secondary to degenerative spondylolisthesis. Its cohort was recruited from 13 centers in 11 states, making it the most generalizable study of stenosis. The characteristics of the participants and the short term outcomes of SPORT as previously reported are comparable to studies both of isolated spinal stenosis and of mixed cohorts of patients with and without degenerative spondylolisthesis with stenosis. 2–4

Few studies have long-term outcomes to compare to SPORT’s, and most of these include mixed cohorts of stenosis with and without some degree of degenerative spondylolisthesis. The Maine Lumbar Spine Study (MLSS)2 cohort had outcomes for 8–10 years. In terms of sciatica bothersomeness, long-term results for the MLSS showed persistent statistically significant benefit for the surgery group (TE = −9.4; p=0.02), similar to the SPORT OBS cohort. However, the MLSS found no difference between treatment groups at 8–10 years in the % satisfied with current symptoms (55% surgery versus 49% non-op; p=0.52) while SPORT showed a persistent advantage for surgery in both the RCT (56% surgery versus 33% non-op; p<0.001) and OBS (64% versus 34%; p<0.001) cohorts.

Two other studies have followed mixed cohorts of stenosis patient with and without degenerative spondylolisthesis, each with 10-years worth of data. One reported on Weber’s original stenosis cohort 26,27 and the other was Slatis/Malmivaara et al’s long term study of a mixed stenosis cohort. 28 Amundsen et al. report a small, persistent advantage for the surgery group at 10 years.27 Slatis et al., reporting the 6 year results of a RCT of moderate spinal stenosis, found a narrowing of the advantage for surgery at 6 years, but with a persistently significant advantage when viewed over the entire time period, similar to the SPORT RCT as-treated results.

There was little evidence of harm from either treatment. In the interval between 4 and 8 years there have not been any cases of paralysis in either the surgical or non-operative group, and there was no statistical difference in morbidity between the surgical and non-operative groups. The 8-year rate of re-operation for recurrent stenosis was 10% and the overall re-operation rate increased from 13% at 4 years to 18% at 8 years, compared to 23% at 8–10 years in the MLSS. The 6-month perioperative mortality rate was extremely low at 0.2%.

CONCLUSION

In the as-treated analysis combining the randomized and observational cohorts of patients with spinal stenosis (SpS) those treated surgically showed significantly greater improvement in pain, function, satisfaction, and self-rated progress over eight years compared to patients treated non-operatively, but with convergence in outcomes between treatment groups after 5 years in the RCT cohort. Preferential loss to follow-up of patients with worse baseline characteristics and early outcomes in both treatment groups could lead to overestimates of long-term outcomes, but not likely bias treatment effect estimates.

Acknowledgments

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s). The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (U01-AR45444, P60-AR048094 and P60-AR062799) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funds were received in support of this work.

Footnotes

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: consultancy, stocks, travel/accommodations/meeting expenses.

Level of Evidence: 1

References

- 1.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson PR, et al. United States’ trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992–2003. Spine. 2006;31:2707–14. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000248132.15231.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas SJ, Deyo RA, Keller RB, et al. The Maine Lumbar Spine Study, Part III. 1-year outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1996;21:1787–94. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608010-00012. discussion 94–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Robson D, et al. Surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis: four-year outcomes from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine. 2000;25:556–62. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200003010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malmivaara A, Slatis P, Heliovaara M, et al. Surgical or nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis?: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2007;32:1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000251014.81875.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis four-year results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:1329–38. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e0f04d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:794–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkmeyer NJ, Weinstein JN, Tosteson AN, et al. Design of the Spine Patient outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine. 2002;27:1361–72. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200206150-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2257–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort. JAMA. 2006;296:2451–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2441–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.20.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA. 2003;290:1624–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1295–304. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummins J, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Descriptive epidemiology and prior healthcare utilization of patients in The Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial’s (SPORT) three observational cohorts: disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2006;31:806–14. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000207473.09030.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, et al. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:907–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware J, Sherbourne D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JJ. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: Nimrod Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine. 2000;25:2940–52. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017. discussion 52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deyo RA, Diehl AK. Patient satisfaction with medical care for low-back pain. Spine. 1986;11:28–30. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198601000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine. 1995;20:1899–908. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00011. discussion 909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: four-year results for the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) Spine. 2008;33:2789–800. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ed8f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K-L, et al. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzmaurice G, Laird N, Ware J. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Philadelphia, PA: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations. J Am Stats Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peto R, Peto J. Asymptotically Efficient Rank Invariant Test Procedures. J R Stat Soc Ser aG. 1972;135:185. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amundsen T, Weber H, Lilleas F, et al. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Clinical and radiologic features. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:1178–86. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amundsen T, Weber H, Nordal HJ, et al. Lumbar spinal stenosis: conservative or surgical management?: A prospective 10-year study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:1424–35. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006010-00016. discussion 35–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slatis P, Malmivaara A, Heliovaara M, et al. Long-term results of surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomised controlled trial. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2011;20:1174–81. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1652-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]