Child neglect is by far the most common form of child maltreatment. Approximately two-thirds of reports to child protective services involve neglect.1 Per a community survey in 2006, the frequency of neglect is 30.6 per 1,000 children, with lower rates of 6.5, 2.4, and 4.1 for physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, respectively.2

Neglect is not as benign as the term suggests. Neglect can have substantial and long-term effects on children’s physical and mental health and cognitive development. Examples include fatalities,1 impaired brain development,3 and adult problems such as liver4 and ischemic heart disease.5 Neglect also has been associated with inferior academic performance,6 emotional, and behavioral problems,7 as well as depression and suicidality decades later.8

Neglect poses challenges to pediatricians. There is often uncertainty regarding what constitutes neglect and how best to address it. This article covers definitional considerations and principles for assessing and addressing neglect, prevention, and advocacy.

DEFINITION OF CHILD NEGLECT

Defining child neglect is not an academic exercise. It guides our thinking and practice concerning identifying and approaching this prevalent problem. State laws focus on omissions in care by parents or caregivers that result in actual or potential harm.9 Parents are held responsible, or culpable, for failing to provide necessary care. The challenge is in knowing whether it is reasonable and constructive to blame a parent for a lapse in care, such as not getting a prescription filled. Understandably, many professionals feel uncomfortable invoking “neglect.”

Parental Responsibility and Blame

Parents are primarily responsible for meeting their children’s needs. However, there are usually multiple and interacting contributors to parenting and to neglect. For example, a single, depressed mother who has lost her job and health insurance may not have filled a prescription for her daughter’s medications. Other situations are even further beyond parental control, such as schools that fail to meet children’s educational needs. Child protection services (CPS), however, typically become involved only when a parental inaction is deemed the major contributor to the child’s need(s) not being met.

Inadequately Met Needs

An alternative to the customary focus on parental omissions is to define neglect as occurring when a child’s basic needs are not adequately met.10 Advantages to this approach include: 1) fitting well with a broad medical goal, which is helping ensure children’s safety, health, and development; 2) being less blaming and more constructive, a key issue as professionals strive to work with families; and 3) drawing attention to other contributors to neglect, aside from parents, thus encouraging a broader response to underlying problems. Clearly, not all circumstances within this child-centered view of neglect warrant CPS involvement; alternative interventions may be more appropriate.

ADEQUATE CARE

The extent to which a child’s needs are met exists on a continuum from optimal to grossly inadequate, often without natural cut points. Crude categories of “neglect” or “no neglect” are too simplistic. It is difficult to determine at what point inadequate emotional support, for example, is harmful. And, with relatively few extreme situations, the proverbial gray zone is large.

How might the adequacy of care be assessed? Examples of adequate health care include: reasonable care for minor problems (eg, parent comforting a child after a fall); professional care sought for more severe problems (eg, child cutting herself); adequate treatment (eg, adherence to treatment regimen); and professional care meets accepted standards. The last example illustrates again how deficits in care are not always due to parents. With the extent to which needs are met being on a continuum, many circumstances may need to be addressed, even if they do not meet the threshold for “neglect.”

ACTUAL VS. POTENTIAL HARM

States’ legal definitions of neglect generally include both actual and potential harm; however, many CPS agencies restrict their practice to circumstances involving actual harm. Nevertheless, potential harm is important; the impact of neglect may be apparent only years later.

It is difficult to predict the likelihood and nature of future harm. Epidemiological data sometimes help, such as the increased risk of a serious head injury from a fall off a bicycle when not wearing a helmet.11 In addition to the likelihood of harm, we should consider the nature of the potential harm. A high likelihood of minor harm (eg, bruising from a short fall) might be acceptable. In contrast, a low likelihood of severe harm (eg, suicide) is unacceptable.

HETEROGENEOUS NATURE OF NEGLECT

The different types of neglect children experience vary considerably. The following are types most commonly encountered by psychiatrists.

Nonadherence with Health Care Recommendations

This form of neglect occurs when recommendations for health care are not implemented, resulting in actual or potential harm. The term “nonadherence” is preferred; it lessens the blaming connotation of “noncompliance.”12 It is important to ascertain the extent to which care was not received, and whether that led to the child’s problem. We should acknowledge that some recommended care may not be important; such lapses should not be labeled neglectful. For example, occasional missed appointments are unlikely to result in harm and should not be considered neglect. Encouragement to keep appointments, however, is reasonable.

Delay or Failure to Provide Health Care

Neglect occurs when necessary health care is not sought in a timely manner, or not at all. CPS typically considers neglect when a parent does not seek care for a significant problem that an “average layperson” can reasonably be expected to act upon, such as severe anorexia.

Cultural and Religious Issues

Another circumstance involves different cultural practices, such as the Southeast Asian folkloric remedy of “cao gio”. Used for a variety of symptoms, cao gio involves vigorous rubbing with a hard object that causes bruising and welts. Concerns of neglect arise when complications ensue, especially when effective medical treatment is available (eg, for depression). The appropriateness of intervening is guided by the level of certainty that the approach used was harmful or ineffective, and that a distinctly preferable treatment exists. The same principles apply when children do not receive medical care for religious reasons. Thirty-four states and the District of Columbia have religious exemptions in their civil codes on child abuse or neglect, exempting parents who do not obtain medical care for sick children based on their religion. The American Academy of Pediatrics strongly opposes these exemptions, advocating that “the opportunity to grow and develop safe from physical harm with the protection of our society is a fundamental right of every child.”13

Overall, the recognition of what constitutes neglect is not very culture-bound. Several US studies found adults from different racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups generally agree on what constitutes child neglect.14 More broadly, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child attests to a remarkable international consensus regarding what children need to ensure their health, development, and safety.15

Failure-to-Thrive and Overweight

The etiology of failure-to-thrive (FTT) is often multifactorial; the old dichotomy of “organic or nonorganic” is no longer recommended as most growth problems involve both nutritional and psychosocial factors. In terms of nutritional needs not being adequately met, most children with FTT can be said to experience neglect. However, CPS focuses on problems where omissions in parental care are primarily responsible.

Pediatric overweight has dramatically increased in prevalence; over 17% of children have a BMI > 95th percentile. The morbidity associated with obesity is clear. Like FTT, the etiology of obesity is multifactorial, and neglect is a concern when the problem is not addressed despite available interventions.

Drug-Exposed Children

Aside from the potential direct harm of the drug, the compromised caregiving abilities of substance-abusing parents are a major concern. Not surprisingly, parental substance abuse has been associated with neglect.

Inadequate Protection from Environmental Hazards

A basic need of children is to be protected from environmental hazards — inside and outside the home. Injuries, exposure to guns and intimate partner violence, and extreme risk-taking behavior may represent inadequate protection and supervision, threatening children’s health, development, and safety. In general, neglect is a concern when there is a pattern of inadequate protection and supervision. A single incident (eg, witnessing parents physically fighting) should probably not be construed as neglect.

New and Other Forms of Neglect

As knowledge evolves concerning children’s health and development, new forms of neglect become apparent. For example, we have learned of the impact of second-hand smoke on children, especially those with pulmonary disease. Attitudes have shifted toward parents who leave guns accessible to children. Twenty-seven states have laws holding parents criminally liable. As the benefits of mental health treatments become increasingly clear, being denied such care may be construed as emotional neglect.

OTHER ASPECTS OF NEGLECT THAT INFLUENCE RESPONSE

Intentionality regarding neglect is a common concern, although it probably does not apply to most neglectful situations. Most parents do not intend to neglect their children. Rather, problems impede their ability to adequately care for them. In practice, as we strive to strengthen families, viewing their shortcomings as intentional may be counterproductive, especially if it fosters a negative stance toward parents. As a practical matter, it’s very difficult to assess intentionality. Even in extreme cases, such as children who are deliberately starved or kept in a basement, establishing specific “intentionality” is not necessary in order to ensure the child’s safety, such as by removal from the neglectful environment.

Context influences our response to neglect. A constructive approach requires understanding the underlying contributors to best tailor an approach that meets the needs of the child(ren) and family.

ETIOLOGY OF CHILD NEGLECT

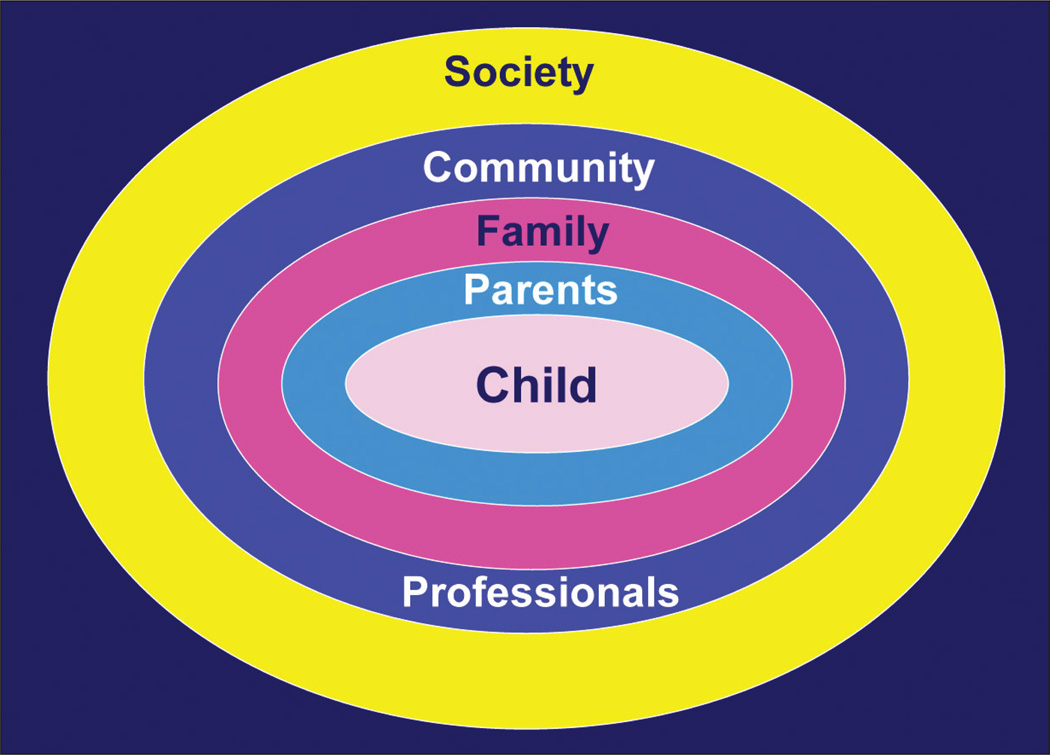

Neglect is best understood as a symptom, with many possible contributors spanning the individual (parent and child), familial, community, and societal levels. Professional actions and inactions may also contribute to neglect. This framework guides a comprehensive assessment of what may underpin neglect, which then guides the intervention. The following examples illustrate each category (see Figure 1 on page 74).

Figure 1.

Contributors to child neglect.

Parents

Mothers’ mental health problems, especially depression and substance abuse, have been linked to neglect.16 Limited involvement of fathers in their children’s lives can also be seen as neglect.17

Child

Child characteristics such as low birth weight, prematurity, or disabilities may challenge parents and contribute to neglect.18 The behavior of older children may be difficult, despite a parent’s appropriate efforts.

Family

Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment frequently co-occur. Children need to feel safe and secure at home, not afraid or threatened.

Community

The community context and its resources influence parent–child relationships and possible neglect. Parents’ negative perceptions of the quality of neighborhood life have been related to maltreatment.19

Professionals

Professionals may also contribute to neglect. Poor communication with parents may result in them not understanding the treatment plan.23 Psychiatrists may not comply with recommended approaches and may fail to identify children’s medical or psychosocial needs, contributing to neglect.

Society

Many broad societal factors compromise parents’ abilities to care adequately for their children. In addition, these societal or institutional problems can be directly neglectful of children. In one study, only 70% of children with learning disabilities received special education services; fewer than 20% of children received needed mental health care.20 Neglected dental care is widespread.21 And if health insurance is a basic need, 7.3 million (9.8%) children experienced this neglect in 2012.22 Such circumstances can be considered societal neglect. In addition, poverty appears strongly associated with neglect,2 as well as impeding children’s health and development. This too, in an affluent society, constitutes societal neglect.

ASSESSMENT OF POSSIBLE NEGLECT

The heterogeneity of neglect does not allow one specific approach for assessing the array of possible circumstances. Instead, a list of general principles and questions are offered in Sidebar 1, and principles for approaching the problem are offered in Sidebar 2.

SIDEBAR 1.

General Principles for Assessment of Possible Neglect

Verbal children should be separately interviewed, at an appropriate developmental level. Possible questions include: “What happens when you feel sick? Who helps you if you have a problem? Who do you go to if you’re feeling sad?”

Do the circumstances indicate that the child’s need(s) is/are not being met adequately? Is there evidence of actual harm? Is there evidence of potential harm and on what basis?

What is the nature of the neglect?

Is there a pattern of neglect? Are there other forms of neglect, or abuse? Has there been prior CPS involvement?

What is the risk of imminent harm, and of what severity?

What is contributing to the neglect? Consider categories listed under “Etiology.”

-

What strengths/resources are there?

-

–

Child (eg, child wants to go to school, requiring better health)

-

–

Parent (eg, parent wants child to be happy)

-

–

Family (eg, other family members willing to help)

-

–

Community (eg, programs for parents, families)

-

–

What interventions have been tried, with what results? What has the psychiatrist done to address the problem?

What is the possibility of other children in the home also being neglected (a common occurrence)?

What is the prognosis? Is the family motivated to improve the circumstances and accept help, or resistant? Are suitable resources, formal and informal, available?

SIDEBAR 2.

General Principles for Addressing Child Neglect

Convey concerns to family, kindly but forthrightly. Avoid blaming.

Be empathic and state interest in helping, or suggest another psychiatrist.

Help address contributing factors, prioritizing those most important and amenable to being remedied (eg, recommend treatment for a mother’s depression). Parents may need their problems addressed to enable them to adequately care for their children. Parenting programs can help.

Begin with least intrusive approach, usually not child protective services.

Establish specific objectives (eg, a child’s hyperactivity will be adequately controlled), with measurable outcomes using standardized rating scales. Similarly, advice should be specific and limited to a few reasonable steps.

Engage the family in developing the plan, solicit their input and agreement.

Build on strengths, providing a valuable hook to engage parents and children.

Encourage positive family functioning, such as how a father can be more involved.

Be innovative and consider available resources, such as using pots and pans for play. Encourage reading to promote both literacy and intimacy. 24

Encourage informal supports from family and friends.

Consider support available through a family’s religious affiliation.

Consider need for concrete services (eg, Medical Assistance, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program).

Consider children’s specific needs, given what is known about the possible outcomes of neglect.

Be knowledgeable about community resources, and facilitate appropriate referrals.

Consider the need to involve child protective services, particularly when moderate or serious harm is involved, and, when less intrusive interventions have failed.

Present the report as necessary to clarify the situation, so that the child and family will get the appropriate help. Most states have recently developed alternative response systems — especially for neglect. This approach focuses on supporting families to do better, rather than on investigating what was done wrong. It attempts to be conciliatory and constructive, rather than punitive. Most importantly, it prioritizes the heart of the problem: addressing the needs of children and families.

A written, signed contract helps document the agreed-upon plan — one copy for the parent and one for the medical chart.

Provide support, follow-up, review of progress, and adjust the plan if needed.

It is important to recognize that neglect often requires long-term intervention with ongoing support and monitoring. Regarding different cultural and religious practices, humility is essential. Avoid an ethnocentric approach (ie, believing “my way is the right way”). Alternatively, although it is important to respect different cultural practices, we should not accept those that clearly harm children. We can work with parents and religious and cultural leaders to seek a satisfactory compromise; however, sometimes agreement cannot be reached and the child is harmed or at risk. Criteria for legal involvement include: 1) the treatment refused by the parents has substantial benefits over the alternative; 2) not receiving the recommended treatment will cause serious harm; 3) with treatment, the child is likely to enjoy a “high quality” of life; and 4) in the case of teenagers, they should consent to treatment.25

CONCLUSION

Pediatricians can help families and neglected children beyond simply treating the child. For example, if CPS has intervened, providers can remain involved after a CPS report in helping the family obtain services. Conferring with specialists is generally helpful, especially so in such circumstances. Efforts to develop a program and to improve policies and institutional practices concerning children and families are other forms of useful advocacy. At the broader level of state and national government, pediatricians can advocate for policies and resources to help meet the needs of children and families. Thus, there are different ways that pediatricians can be effective advocates on behalf of neglected children.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES.

Learn how to manage the complexities of defining neglect in children.

Examine the multiple contributors to neglect.

Understand principles for effectively intervening in a child neglect situation.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Dubowitz has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Child maltreatment, 2010. U.S. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2011. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children Youth and Families. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, et al. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4): Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teicher MH, Dumont NL, Ito Y, et al. Childhood neglect is associated with reduced corpus callosum area. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(2):80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dong M, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Giles WH, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and self-reported liver disease: new insights into a causal pathway. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(16):1949–1956. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.16.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, et al. Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation. 2004;110(13):1761–1766. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143074.54995.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckenrode J, Kendall-Tackett KA. The effects of neglect on academic achievement and disciplinary problems: a developmental perspective. Child Abuse Negl. 1996;20(3):161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(95)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubowitz H, Papas MA, Black MM, Starr RH. Child neglect: outcomes in high-risk urban preschoolers. Pediatrics. 2002;109(6):1100–1107. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the adverse childhood experiences study. JAMA. 2001;286(24):3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DePanfilis D. How do I determine if a child is neglected? In: Dubowitz H, DePanfilis D, editors. Handbook for Child Protection Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubowitz H, Black M, Starr R, Zuravin S. A conceptual definition of child neglect. Criminal Justice Behav. 1993;20(1):8–26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wesson D, Spence L, Hu X, Parkin P. Trends in bicycling-related head injuries in children after implementation of a community-based bike helmet campaign. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35(5):688–689. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2000.5944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liptak GS. Enhancing patient compliance in pediatrics. Pediatr Rev. 1996;17(4):128–134. doi: 10.1542/pir.17-4-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Religious objections to medical care. Pediatrics. 1997;99(2):279–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubowitz H, Klockner A, Starr R, Black MM. Community and professional definitions of neglect. Child Maltreatment. 1998;3(3):235–243. [Google Scholar]

- 15.UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. [Accessed Feb. 20, 2013]; Available at: www.unicef.org/crc.

- 16.Ondersma SJ. Predictors of neglect within low socioeconomic status families: the importance of substance abuse. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72(3):383–391. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubowitz H, Black MM, Kerr M, Starr RH, Harrington D. Fathers and child neglect. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(2):135–141. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaudes PK, Mackey-Bilaver L. Do chronic conditions increase young children’s risk of being maltreated? Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32(7):671–681. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garbarino J, Sherman D. High-risk neighborhoods and high-risk families: the human ecology of child maltreatment. Child Dev. 1980;51(1):188–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, et al. Children’s mental health service use across service sectors. Health Aff (Millwood) 1995;14(3):147–159. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung LH, Shain SG, Stephen SM, Weintraub JA. Oral health status of San Francisco public school kindergarteners 2000–2005. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66(4):235–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2006.tb04075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uninsured children. [Accessed Feb. 20, 2013]; Available at: www.childrensdefense.org/policy-priorities/childrens-health/uninsured-children.

- 22.Farrell MH, Kuruvilla P. Assessment of parental understanding by pediatric residents during counseling after newborn genetic screening. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(3):199–204. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam BC, Lee J, Lau YL. Hand hygiene practices in a neonatal intensive care unit: a multimodal intervention and impact on nosocomial infection. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e565–e571. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duursma E, Augustyn M, Zuckerman B. Reading aloud to children: the evidence. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(7):554–557. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.106336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bross DC. Medical care neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 1982;6(4):375–381. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(82)90080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]