Abstract

BACKGROUND

The relative importance of the fourth (K4) and fifth (K5) Korotkoff phases as the indicator of diastolic blood pressure (DBP) levels among children remains uncertain.

METHODS

In a sample of 11,525 youth aged 5–17, we examined interexaminer differences in these 2 phases and the relation of theses 2 phases to adult blood pressure levels and hypertension. The longitudinal analyses were conducted among 2,156 children who were re-examined after age 25 years.

RESULTS

Mean (±SD) levels of DBP were 62 (±9) mm Hg (K4) and 49 (±13) mm Hg (K5). K4 showed less interobserver variability than did K5, and 7% of the children had at least 1 (of 6) K5 value of 0mm Hg. Longitudinal analyses indicated that K4 was more strongly associated with adult blood pressure levels and hypertension. In correlational analyses of subjects who were not using antihypertensive medications in adulthood (n = 1,848), K4 was more strongly associated with the adult DBP level than was K5 (r = 0.22 vs. 0.17; P < 0.01). Analyses of adult hypertension (based on high blood pressure levels or use of antihypertensive medications) indicated that the screening performance of childhood levels of K4 was similar to that of systolic blood pressure and was higher than that of K5, with areas under the receiver operator characteristic curves of 0.63 (systolic blood pressure), 0.63 (K4), and 0.57 (K5).

CONCLUSIONS

As compared with K5 levels among children, K4 shows less interobserver variability and is more strongly associated with adult hypertension.

Keywords: blood pressure, children, diastolic blood pressure, hypertension, Korotkoff phases, longitudinal, systolic blood pressure.

Although the onset of the fifth Korotkoff phase (K5, beginning of silence) is widely used among adults as the indicator of diastolic blood pressure (DBP), it is unclear whether K5 or the fourth Korotkoff phase (K4, muffling of sounds) should be used for children and adolescents. The most recent (2004) recommendation1 is to use K5 for all children and adolescents, but a 2008 meta-analysis found that adult DBP levels show a slightly stronger correlation with childhood levels of K4 than K5.2 Neither K4 nor K5 correlates strongly with the intra-arterial DBP of children.3–5

The recommendations for the assessment of DBP among children in the United States have changed considerably over time. In 1977, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Task Force Report on Blood Pressure Control in Children recommended that K4 be used for all children and adolescents,6 whereas the 1987 recommendation was to use K4 only for children aged <13 years.7 It was acknowledged that in some children, the K4 and K5 phases may occur together and that sounds can sometimes be heard even at 0mm Hg.7 Subsequent reports in 19968 and 20041 recommended that K5 be used as the indicator of DBP for all children and adolescents. Formulas have also been given for levels of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and K5, but not K4, that can be used to standardize a child’s blood pressure level for sex, age, and height.1

There is, however, little longitudinal data available to determine whether the K4 or K5 level, measured by the same observer, is more strongly related to adult hypertension.9 The purpose of these analyses is to describe, in a large population-based study, the distribution of K4 − K5 differences and the relation of these 2 phases to adult hypertension. We use data from 26,356 examinations of youth aged 5–17 years obtained from 11,525 children in the Bogalusa Heart Study. Of the 2,156 children who were re-examined after age 25 years, 401 were hypertensive.

METHODS

Study population

The Bogalusa Heart Study focuses on the natural history of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in a biracial community (1/3 black) in Washington Parish, Louisiana.10 Seven cross-sectional studies of schoolchildren were conducted between 1973–1974 and 1992–1994. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and study protocols were approved by institutional review boards.

Each of these studies examined approximately 3,500 children and adolescents. Of the 26,518 examinations conducted among youth aged 5–17 years, we excluded 137 examinations with missing blood pressure information and 56 examinations because height was missing or race was reported as other than white or black. This resulted in 26,356 examinations conducted among 11,525 children; approximately 60% of the children participated in >1 examination.

To follow these children as they aged, adults were examined in studies conducted from 1977 through 2010,11 and our longitudinal analyses are restricted to subjects who were re-examined after age 25 years. Of the 5,504 examinations conducted among these adults, we excluded 78 examinations with missing blood pressure data or among women who were pregnant. These exclusions resulted in a group of 2,156 adults aged 25–51 years, and we used data from only their final examination. Of these adults, 401 were considered to have hypertension based on either reported use of antihypertensive medication, SBP ≥140mm Hg, or DBP ≥90mm Hg.

Examination methods

The standardized examination procedures used in the Bogalusa Heart Study have been described.10 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as kilograms per meter squared, and obesity among those aged 5–17 years was defined as a BMI-for-age ≥95th percentile of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts12 or a BMI ≥30kg/m2. Adult obesity is based on a BMI ≥30kg/m2.

Blood pressure observers, who were monitored throughout the examinations, recorded the onset of the first, fourth (muffling of sounds), and fifth (beginning of silence) Korotkoff phases. Observer training, including audiometric tests and the use of double stethoscopes with 2 mercury columns, was emphasized throughout the study period.13,14 Attempts were made to minimize the influence of the emotional state of the child.15 Cuff sizes were selected according to a protocol based on the circumference and length of the upper arm, using a bladder width as large as possible while leaving room for the stethoscope at the elbow skin crease.15,16

Right arm sitting levels of SBP, K4, and K5 were each measured 3 times by 2 observers using a mercury sphygmomanometer.10,13 As has been done in previous analyses of data from the Bogalusa Heart Study,10,13,15,17,18 we used the mean of the 6 recorded measurements for SBP, K4, and K5. There were 1,962 (7.4%) children who had at least 1 (of 6) K5 values recorded as 0mm Hg, and most analyses treat these 0 values no differently than any other when calculating the mean K5 value. Only 34 (0.1%) children had all 6 K5 measurements recorded as 0mm Hg.

The longitudinal analyses, which contrasted the relation of childhood levels of K4 and K5 to adult blood pressure levels and hypertension, also compare our method for calculating mean K5, which treated the 0mm Hg values no differently than any other recorded value, with 3 other methods. In addition to using all recorded values of K5, we also calculated the mean K5 after (i) excluding the 0mm Hg values, (ii) replacing the K5 value of 0mm Hg with the corresponding K4 value, and (iii) replacing the K5 readings <20mm Hg with the corresponding K4 value. Given 3 recorded K5 values of 0, 15, and 55mm Hg, for example, the calculated mean K5 under in method 2 would be (1st K4 + 15 + 55) / 3 rather than 23.3 ((0 + 15 + 55)/3) mm Hg. “The Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents”1 recommends that K4 should be used as the DBP if the K5 value remains “very low” after reducing pressure on the stethoscope head.

To increases the comparability of our longitudinal results with those of other studies, the longitudinal analyses are based on the 3 measurements from the first observer (rather than the 6 measurements from 2 observers). Adult DBP is based on K5.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed with R.19 We examined the distributions of the K4 − K5 difference and their relation to the differences between the 2 examiners. Longitudinal analyses, in the cohort of 2,156 children who were re-examined after age 25 years, examined whether levels of K4 and K5 were correlated similarly with adult DBP levels (H0: r K4 vs. adult DBP = r K5 vs. adult DBP) among subjects who were not using antihypertensive medications in adulthood. The statistical significance of the differences between correlation was assessed using the paired.r function.20 To account for differences in childhood levels of blood pressure by sex, age, and height, blood pressure levels in the longitudinal analyses were converted into z scores using formulas from the Fourth Report.1 We also assessed the potential impact of obesity on the observed associations by using the residuals of various regression models that predicted levels of SBP, K4, and K5 from sex, age, height, and BMI.

The ability of childhood levels of SBP, K4, and K5 to identify adult hypertension (based on use of antihypertensive medications, SBP ≥140mm Hg, or DBP ≥90mm Hg) was examined in 2×2 tables; 308 of the 401 adults with hypertension reported taking antihypertensive medications. Because only 15 (0.7%) children in these analyses had a mean K4 that was ≥95th percentile given in the Fourth Report1 and no child had a mean K5 above this cut point, we selected various childhood cut points that resulted in fairly similar prevalences of high childhood levels and adult hypertension (18.6%). Childhood blood pressure levels in Bogalusa, which are based on 6 measurements, are generally lower than in other reports,3 but many other studies obtain only 1 blood pressure measurement.21

We also examined the screening performance of SBP, K4, and K5 over all possible cut points by comparing the area under the receiver operator characteristic curves (AUC).22 These curves account for the trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity across cut points, and AUC can be interpreted as the probability that the childhood blood pressure of a randomly chosen hypertensive adult was higher than the childhood level of a nonhypertensive adult. Differences between AUCs were assessed using the pROC package23 or by bootstrapping the logistic regression C-statistic.24

RESULTS

Table 1 shows mean levels of various characteristics among children and adults. The mean (±SD) age of the examined children was 11.2 (±3) years (range = 5.0–17.9 years), and the prevalence of obesity was 9%. Although mean levels of blood pressure did not differ greatly between boys and girls, given the large number of examinations (n = 26,356), most of the observed differences were statistically significant. Boys had slightly higher levels of SBP, but girls had slightly higher levels of both K4 and K5. K4 − K5 differences varied from 0 to 76mm Hg (mean = 13.4±7mm Hg). A K5 value of 0mm Hg was recorded for ≥1 of the 6 measurements at 1,962 (7.4%) examinations and was more likely to occur among boys and younger children. The mean age at examination in adulthood was 36.5±7 years.

Table 1.

Mean levels of various characteristics among children and adults

| Characteristic | Children | Adults | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Men | Women | |

| No. of examinationsa | 13,402 | 12,954 | 947 | 1,209 |

| Age, y | 11.2±4 | 11.2±4 | 36.6±7 | 36.4±7 |

| % Black | 38% | 39% | 30% | 32% |

| Year of examination | 1,981±6 | 1,981±6 | 2,001±8 | 2,001±8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18.7±4* | 19.0±4* | 28.9±6 | 28.8±8 |

| Obeseb | 9% | 9% | 36% | 37% |

| SBP, mm Hg | 102±11* | 102±11* | 120±14* | 113±14* |

| SBP z score | −0.3±0.8 | −0.2±0.8 | — | — |

| K4, mm Hg | 62±9* | 63±9* | — | — |

| K4 z score | 0±0.7* | 0.1±0.7* | — | — |

| K5, mm Hg | 47±13* | 50±13* | 74±11* | 70±10* |

| K5 z score | −1.2±1.0* | −1.1±1.1* | — | — |

| K4 − K5 difference, mm Hg | 14±7* | 13±7* | — | — |

| At least one K5 of 0mm Hgc | 8.7%* | 6.2%* | — | — |

With the exception of the sample size, values are mean ± SD or percentages.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; K4, fourth Korotoff phase; K5, fifth Korotoff phase; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

aChildhood estimates are based on levels recorded from the 26,356 examinations (representing data from 11,525 subjects). Adult estimates are based on 2,156 examinations; each adult was examined only once.

bBased on a BMI ≥95th percentile of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reference population or a BMI ≥30kg/m2.

cTwo observers each recorded 3 measurements for each child.

*P < 0.01 for sex difference among children or adults. Analyses of sex differences among children accounted for the within-child clustering of levels of BMI and blood pressure using the Huber–White method 23 and multilevel models. 37

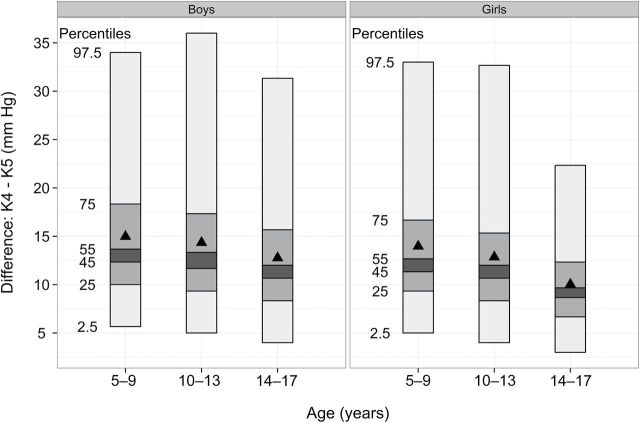

The correlation between levels of K4 and K5 was 0.84. Approximately 14% of the children had a K4 − K5 difference ≥20mm Hg, and 2.5% (the 97.5th percentile) had a difference ≥33mm Hg (Figure 1). The mean K4 − K5 difference was approximately 2mm Hg higher among youth aged 5–9 years than among youth aged 14–17 years and was 1.5mm higher among boys than among girls.

Figure 1.

Percentile plots of the fourth Korotoff phase (K4) and fifth Korotkoff phase (K5) difference by sex and age group. Each bar includes the middle 95% (2.5th percentile to 97.5th percentile) of the distribution, and the horizontal lines represent various percentiles. The dark triangle represents the mean difference. Boys are on the left; girls are on the right.

The mean interobserver differences were 7±6 (K4) and 10±9 (K5) mm Hg, and both interobserver differences were larger among younger children than among older children. In addition, the K4 − K5 difference was correlated with the interobserver difference for K5 (r = 0.42) but not with the interobserver difference for K4 (r = 0.08). As shown in Table 2, as the K4 − K5 difference varied from <10mm Hg to ≥40mm Hg (2nd column of values), mean levels of K4 and the interobserver difference for K4 did not substantially change. In contrast, the K5 interobserver difference varied by approximately 15mm Hg across categories of K4 − K5 and the percentage of children with at least 1 K5 value of 0mm Hg (final column) varied from 0.1% to approximately 97%.

Table 2.

Relation of fourth Korotoff phase and fifth Korotoff phase difference to mean blood pressure levels and to interobservera differences among children

| Sex | K4 – K5, mm Hg | No. | K4 | K5 | At least 1 K5 value of 0mm Hg, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Interobserver difference, mm Hg | Mean | Interobserver difference, mm Hg | ||||

| Overall | — | 26,356 | 62±9 | 6.9±6 | 49±13 | 10.4±9 | 7.4 |

| Boys | 0–9 | 4,346 | 64±9 | 6.4±5 | 56±9 | 7.7±6 | 0.1 |

| 10–19 | 6,842 | 61±9 | 7.0±6 | 47±9 | 10.1±8 | 2.7 | |

| 20–29 | 1,652 | 58±9 | 7.9±7 | 35±10 | 17.2±13 | 30.8 | |

| 30–39 | 424 | 57±9 | 7.9±8 | 23±9 | 26.8±16 | 77.6 | |

| ≥40 | 138 | 61±9 | 8.5±7 | 15±9 | 24.1±17 | 96.4 | |

| Girls | 0–9 | 5,549 | 65±9 | 6.3±5 | 58±10 | 7.5±6 | 0.1 |

| 10–19 | 5,949 | 62±9 | 7.1±6 | 48±10 | 10.0±8 | 2.6 | |

| 20–29 | 1,085 | 58±9 | 7.2±6 | 34±10 | 16.1±12 | 30.9 | |

| 30–39 | 274 | 57±9 | 7.8±7 | 23±9 | 24.2±16 | 78.1 | |

| ≥40 | 97 | 59±9 | 8.3±8 | 14±9 | 23.3±18 | 97.9 | |

aEach of the 2 observers recorded 3 measurements for both the fourth Korotoff phase (K4) and the fifth Korotoff phase (K5). Mean values of K4 and K5 are based on the mean of the 6 measurements.

The relation of childhood levels of K4 and K5 to adult (age ≥ 25 years) levels of DBP and SBP are shown in Table 3 for the 1,848 subjects who were not taking antihypertensive medications at follow-up. As compared with childhood levels of K5, levels of K4 were more strongly associated with adult DBP (r = 0.22 vs. 0.17; P < 0.001 for difference). The K4 vs. K5 difference varied somewhat across categories of the examined characteristics, but in no case was adult DBP more strongly correlated with the childhood level of K5 than with K4. Additional analyses that used regression models to express levels of childhood blood pressure relative to children of the same sex, age, height, and weight yielded very similar results (data not shown).

Table 3.

Longitudinal relation of fourth Korotoff phase and fifth Korotoff phase levels among children to adult blood pressure levelsa

| Category | Category | No. | Adult DBPb | Adult SBP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child K4 | Child K5 | Child K4 | Child K5 | |||

| Overall | — | 1,848 | 0.22* | 0.17* | 0.17* | 0.08* |

| Sex | Boys | 811 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.19* | 0.12* |

| Girls | 1,037 | 0.26* | 0.20* | 0.22* | 0.11* | |

| Race | White | 1,315 | 0.23* | 0.17* | 0.19* | 0.07* |

| Black | 533 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.09 | |

| Childhood age, y | <12 | 732 | 0.26* | 0.18* | 0.17* | 0.07* |

| 12–13.9 | 502 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.17* | 0.05* | |

| ≥14 | 614 | 0.21* | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.08 | |

| Adult age, y | 25–29 | 574 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.19* | 0.10* |

| 30–39 | 645 | 0.22* | 0.15* | 0.16* | 0.05* | |

| 40–51 | 629 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.17* | 0.09* | |

Abbreviations: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

aAnalysis is restricted to the 1,848 of the 2,156 adults who did not report using antihypertensive medications. Values are correlation coefficients between child and adult levels of specified blood pressure z scores. Childhood fourth Korotoff phase (K4) and fifth Korotoff phase (K5) measurements represent the mean of the 3 measurements from the first observer averaged over all examinations.

bK5 was used as the adult DBP.

*P < 0.01 for difference in the correlation between K4 and K5.

We then examined the cross-classification of childhood blood pressure with adult hypertension (Table 4). Based on the use of the 80th percentile of the blood pressure z scores as the cut point for a “high” childhood level, the sensitivities (33%) and specificities (83%) of SBP and K4 were almost identical. In contrast, the use of K5 resulted in a lower sensitivity (28%) at approximately the same specificity (82%). The use of the 75th percentile as the cut point (bottom of table) resulted in a sensitivity of K4 that was 4 percentage points higher (38% vs. 34%) than that of K5.

Table 4.

Classification of adult hypertension by childhood levels of systolic and diastolic blood pressure

| Childhood cut pointa | Childhood measurement | Adult hypertension | Sensitivityb | Specificityb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| 80th percentile | High SBP | Yes | 137 | 294 | ||

| No | 264 | 1,461 | 33% (2) | 83% (1) | ||

| High K4 | Yes | 134 | 297 | |||

| No | 267 | 1,458 | 33% (2) | 83% (1) | ||

| High K5 | Yes | 112 | 319 | |||

| No | 289 | 1,436 | 28% (2) | 82% (1) | ||

| 75th percentile | High SBP | Yes | 160 | 379 | ||

| No | 241 | 1,376 | 38% (2) | 78% (1) | ||

| High K4 | Yes | 154 | 385 | |||

| No | 247 | 1,370 | 38% (2) | 78% (1) | ||

| High K5 | Yes | 135 | 404 | |||

| No | 266 | 1,351 | 34% (2) | 77% (1) | ||

aA high childhood blood pressure z score was defined so that the upper 20% or 25% of the children would be classified as having a high level. The prevalence of adult hypertension was 18.6% and was based on a systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140mm Hg, a diastolic blood pressure ≥90mm Hg, or reported use of antihypertensive medications. The childhood blood pressure level represents the mean of the 3 measurements from the first observer averaged over all examinations for that subject.

bStandard errors are shown in parentheses.

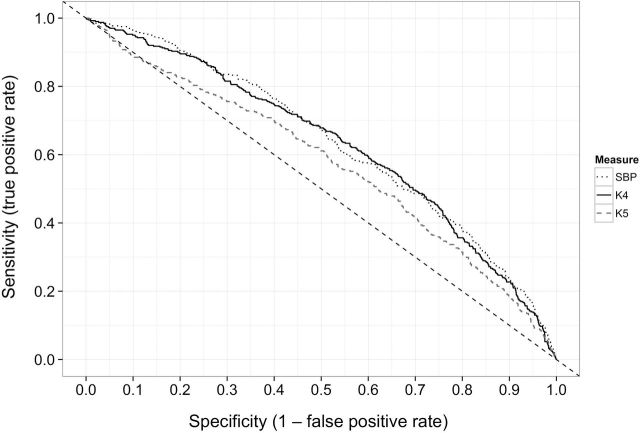

The performance of childhood blood pressure levels in identifying those who had adult hypertension is shown in Figure 2, which plots the specificity (x-axis) vs. sensitivity (y-axis) across all possible cut points of the childhood z scores for SBP, K4, and K5. At all levels of specificity, the sensitivities of both SBP and K4 were higher than that of K5.

Figure 2.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for the classification of adult hypertension by childhood levels of systolic blood pressure (SBP), fourth Korotoff phase (K4), and fifth Korotkoff phase (K5). The 3 curves show the sensitivity (y-axis) and specificity (x-axis) of each blood pressure measure at all possible cut points, and a better classifier would have a curve that is shifted upwards (higher sensitivity at the same specificity). Both SBP and K4 were more strongly (P < 0.001) associated with adult hypertension than was K5. The dashed line, which has a slope of −1, indicates the curve that would be expected if there was no relation of childhood blood pressure levels to adult hypertension.

The predictive accuracies, as assessed by the AUCs (Table 5), were 0.63 (SBP), 0.63 (K4), and 0.57 (K5); The P values were 0.73 for the difference between SBP and K4 and <0.001 for the difference between K4 and K5. In this analysis, the mean K5 was calculating by including the 0mm Hg measurements. We found, however, that substituting the recorded K4 value for either the 0mm Hg K5 values or for those K5 values <20mm Hg, as well as omitting the 0mm Hg K5 recordings, increased the calculated AUC for K5 only slightly (lines 4–6 in Table 5).

Table 5.

Areas under the receiver operator characteristic curve for the classification of adult hypertension by childhood blood pressure levels

| Childhood blood pressure predictora | Overall | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.61 |

| K4 (reference) | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| K5b | 0.57** | 0.59* | 0.57** |

| K5 values of 0mm Hg replaced by K4 value | 0.59** | 0.60 | 0.59* |

| K5 values <20mm Hg replaced by K4 value | 0.59** | 0.61 | 0.59* |

| K5 values of 0mm Hg deleted from calculation of mean K5c | 0.59** | 0.60 | 0.58* |

Abbreviations: K4, fourth Korotoff phase; K5, fifth Korotoff phase; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

aAll childhood levels were expressed as z scores that accounted for sex, age, and height. Childhood measurements represent the mean of the 3 measurements from the first observer.

bIndividuals measurements of 0mm Hg were included in the calculation of the mean.

cSix children were excluded because the 3 K5 measurements were recorded as 0mm Hg.

*P for the difference between the area under the curve for K4 (reference) and the area under the curve for SBP or K5 < 0.05; *P for the difference between the area under the curve for K4 (reference) and the area under the curve for SBP or K5 < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Although K5 is recommended as the indicator of DBP among children and adolescents,1 our results indicate that K4 is a better predictor of adult hypertension. Although the differences in the screening performance of K4 and K5 were not large (a 4% difference in sensitivity) at specificities ≥75%, K4 showed a higher sensitivity at all levels of specificity than did K5. Approximately 7% of the examined children had at least 1 (of 6) K5 measurement of 0mm Hg, and we found that the predictive accuracy of K5 was improved only slightly by either replacing very low K5 readings with the corresponding K4 or by excluding the 0mm Hg readings from the calculation of mean K5.

The guidelines for DBP measurement have changed many times since 1939 when a US–UK committee recommended using K4.25 The current recommendations to use K5 among children and adolescents is largely based not on the ability of K5 to predict adult levels of DBP or hypertension but on the reported similarity of K4 and K5 levels among most children, and the ease with which K5 can be heard. Sinaiko et al.,26 for example, concluded that the choice of K4 or K5 was relatively inconsequential because of the small differences they observed among youth aged 10–15 years. However, the generalizability of these results, particularly to younger children, is uncertain, and it is likely that examiner training greatly influences the accuracy and precision of DBP measurements. Recent analyses of DBP levels among children have been based on either K427 or K5,28 with little justification of either decision.

In our analyses, we found that the K4 vs. K5 difference was <5mm Hg for only 4% of the 26,000 examinations and that the mean difference was 13mm Hg. Other studies of school-aged children have reported mean K4 − K5 differences of approximately 5,26 7,29,30 8–10,31 and 10mm Hg.9,32 Several investigators have also observed that it is more difficult to measure levels of both K4 and K5 than SBP.33–35 Although it has also been suggested that the assessment of K5 (complete disappearance) is easier than K4 (muffling of sounds),36 others have emphasized that the K5 measurements can be more difficult because K4 sounds frequently fade rather than abruptly cease.34 Based on audio recordings of Korotkoff phases among youth aged 11 years (n = 20), O’Sullivan et al.34 reported that 20% had sounds that persisted to the end of deflation (30mm Hg).

Few studies of children have examined the relation of K4 and K5 to intra-arterial DBP. A 1963 study of 120 children concluded that the intra-arterial DBP of children was between K4 and K55 but that neither was strongly correlated with the true DBP. However, a more recent study of infants and children (aged ≤36 months) found that both K4 and K5 overestimated the intra-arterial DBP, with K4 showing a 5mm Hg larger mean bias.4 A relatively low correlation between direct and indirect DBP levels has also been observed in adults.37

Another consideration is that K5 may be absent among children, and 7.4% of the examinations in our study had at least 1 (of 6) K5 values recorded as 0mm Hg. Although this prevalence may seem high, in the 2007–2010 cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2009-2010/BPX_F.htm), approximately 5% of youth aged 8–18 year had at least 1 (of 3) K5 measurements recorded as 0mm Hg. Although the current recommendation is to replace persistent, very low K5 values with K4 values,1 the classification of “very low” values is uncertain. As assessed by the ability to predict adult hypertension, we found that the inclusion of very low K5 values or their substitution with K4 made little difference when estimating the sensitivity and specificity of the mean of 3 measurements. Recent NHANES data exclude K5 measurements of 0mm Hg from the calculation of mean DBP.38

Our results concerning the association of blood pressure levels in childhood and adulthood agree well with previous reports.2,9,17,39 A 2008 meta-analysis of 50 studies,2 for example, found that the childhood level of K4 tended to be more strongly associated with adult DBP levels than childhood levels of K5, but the difference between correlation coefficients (∆ = 0.035) was not statistically significant. A limitation, however, of this type of analysis is that those adults taking antihypertensive medications are typically excluded, resulting in a nonrepresentative sample. Furthermore, only 2 of the 50 studies included in this analysis measured both K4 and K5 with a follow-up that occurred after age 18 years. In our study, 58% of the adults classified as having hypertension were using antihypertensive medications and did not have elevated blood pressure levels at the examination, and this type of analysis is likely to be superior to excluding those using antihypertensive medications. However, because only 2,156 (of 11,525) children were in the longitudinal analyses and no other cohort study has compared the tracking of K4 and K5 from childhood to adulthood, it would be helpful to know if the DBP differences that we observed also exist in other cohorts.

Attempts were made in the Bogalusa Heart Study to follow the same blood pressure protocol over all cross-sectional examinations. Six measurements were obtained in a relaxed environment, resulting in blood pressures that are generally lower than those in other studies of children,13 many of which are based on a single measurement. However, because our focus was the K4 − K5 difference, it is uncertain how this could have biased our results. In addition, the observer training included recurring audiometric testing, the use of tapes and films, and interobserver comparisons using double stethoscopes.13,14 There may, however, have been methodological differences over the period of data collection, and there was evidence of digit preference, with readings that ended in 0 being recorded 2–3 times as frequently as other values. It is also possible that the observer training, which emphasized the change in pitch at K4, was unable to sensitize observers for the disappearance of sounds.40 It is also known that even small amounts of pressure on the stethoscope head can lead to artificially low K5 measurements.33,36 Although it is also possible that our longitudinal analyses were subject to a participation bias, this seems unlikely because participation would have to be related to the K4 − K5 difference.

Recommendations concerning the use of K4 or K5 as the DBP of children and adolescents have changed considerably over time. Although the assessment of K4 and K5 can be strongly influenced by examiner training, our data suggest that K4 should be used as the indicator of DBP among children and adolescents because it shows less interobserver variability and is more predictive of adult hypertension.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grant AG-16592 from the National Institutes of Aging.

REFERENCES

- 1. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2004; 114:555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen X, Wang Y, Appel LJ, Mi J. Impacts of measurement protocols on blood pressure tracking from childhood into adulthood: a metaregression analysis. Hypertension 2008; 51:642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moss AJ. Criteria for diastolic pressure: revolution, counterrevolution, and now a compromise. Pediatrics 1983; 1:854–855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knecht KR, Seller JD, Alpert BS. Korotkoff sounds in neonates, infants, and toddlers. Am J Cardiol 2009; 103:1165–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moss AJ, Adams FH. Index of indirct estimation of diastolic blood pressure. Muffling versus complete cessation of vascular sounds. Am J Dis Child 1963; 106:364–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blumenthal S, Epps RP, Heavenrich R, Lauer RM, Lieberman E, Mirkin B, Mitchell SC, Boyar Naito V, O’Hare D, McFate Smith W, Tarazi RC, Upson D. Report of the Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children. Pediatrics 1977; 59:797–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children. Report of the Second Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children—1987. Pediatrics 1987; 79:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on Hypertension Control in Children and Adolescents. Update on the 1987 Task Force report on high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 1996; 98:649–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biro FM, Daniels SR, Similo SL, Barton BA, Payne GH, Morrison JA. Differential classification of blood pressure by fourth and fifth Korotkoff phases in school-aged girls. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. Am J Hypertens 1996; 9:242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berenson GS, McMahan CA, Voors AW, Webber LS, Srinivasan SR, Frank GC, Foster TA, Blonde C. Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Children: The Early Natural History of Atherosclerosis and Essential Hypertension. Oxford University Press: New York, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Croft JB, Webber LS, Parker FC, Berenson GS. Recruitment and participation of children in a long-term study of cardiovascular disease: the Bogalusa Heart Study, 1973–1982. Am J Epidemiol 1984; 120:436–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Wei R, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL. 2000 CDC Growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 2002; 11:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berenson GS, Cresanta JL, Webber LS. High blood pressure in the young. Annu Rev Med 1984; 5:535–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cresanta JL, Burke GL. Determinants of blood presure levels in children and adolescents. In Berenson GS. (ed), Causation of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Children. Raven Press: New York, 1986, pp. 158–189. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Voors AW, Foster TA, Frerichs RR, Webber LS, Berenson GS, Avenue G. Studies of blood pressures in children, ages 5–14 years, in a total biracial community: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Circulation 1976; 54:319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Voors AW. Cuff bladder size in a blood pressure survey of children. Am J Epidemiol 1975; 101:489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Elkasabany AM, Urbina EM, Daniels SR, Berenson GS. Prediction of adult hypertension by K4 and K5 diastolic blood pressure in children: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr 1998; 132:687–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr 2007; 150:12–17 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. http://www.r-project.org/.

- 20. Revelle W.psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research, version 1.3.2. http://cran.r-project.org/package=psych.

- 21. Fixler DE, Kautz JA, Dana K. Systolic blood pressure differences among pediatric epidemiological studies. Hypertension 1980; 2:I3–I7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Florkowski CM. Sensitivity, specificity, receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves and likelihood ratios: communicating the performance of diagnostic tests. Clin Biochem Rev 2008; 29:S83–S87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez J-C, Müller M. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics 2011; 12:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harrell FE., Jr rms: Regression Modeling Strategies. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rms/index.html.

- 25. A Joint Report of the Committees Appointed by the Cardiac Society of Great Britain and Ireland and the American Heart Association. Standardization of methods of measuring the arterial blood pressure. Br Heart J 1939; 1:261–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sinaiko AR, Gomez-Marin O, Prineas RJ. Diastolic fourth and fifth phase blood pressure in 10-15-year-old children. The Children and Adolescent Blood Pressure Program. Am J Epidemiol 1990; 132:647–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xi B, Zhao X, Chandak GR, Shen Y, Cheng H, Hou D, Wang X, Mi J. Influence of obesity on association between genetic variants identified by genome-wide association studies and hypertension risk in Chinese children. Am J Hypertens 2013; 26:990–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steinthorsdottir SD, Eliasdottir SB, Indridason OS, Palsson R, Edvardsson VO. The relationship between birth weight and blood pressure in childhood: a population-based study. Am J Hypertens 2013; 26:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johnson BC, Epstein FH, Kjelsberg MO. Distributions and familial studies of blood pressure and serum cholesterol levels in a total community—Tecumseh, Michigan. J Chronic Dis 1965; 18:147–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Uhari M, Nuutinen M, Turtinen J, Pokka T. Pulse sounds and measurement of diastolic blood pressure in children. Lancet 1991; 338:159–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fixler DE, Laird WP, Fitzgerald V, Stead S, Adams R. Hypertension screening in schools: results of the Dallas study. Pediatrics 1979; 63:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Labarthe DR, Dai SF, Fulton JE, Harrist RB, Shah SM, Eissa MA, Berenson GS. Systolic and fourth-and fifth-phase diastolic blood pressure from ages 8 to 18 years: Project HeartBeat! Am J Prev Med 2009; 37:S86–S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weismann DN. Systolic or diastolic blood pressure significance. Pediatrics 1988; 82:112–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O’Sullivan J, Allen J, Murray A. A clinical study of the Korotkoff phases of blood pressure in children. J Hum Hypertens 2001; 15:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rosner B, Cook NR, Evans DA, Keough ME, Taylor JO, Polk BF, Hennekens CH. Reproducibility and predictive values of routine blood pressure measurements in children. Comparison with adult values and implications for screening children for elevated blood pressure. Am J Epidemiol 1987; 126:1115–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Londe S. Blood pressure measurement. Pediatrics 1987; 80:967–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ellestad MH. Reliability of blood pressure recordings. Am J Cardiol 1989; 63:983–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Tech/Blood Pressure Procures Manual. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_09_10/BP.pdf.

- 39. Nelson MJ, Ragland DR, Syme SL. Longitudinal prediction of adult blood pressure from juvenile blood pressure levels. Am J Epidemiol 1992; 136:633–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Voors AW, Webber LS, Berenson GS. A choice of diastolic Korotkoff phases in mercury sphygmomanometry of children. Prev Med (Baltim) 1979; 8:492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]