Abstract

Protein lysine malonylation, a newly identified protein post-translational modification (PTM), has been proved to be evolutionarily conserved and is present in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. However, its potential roles associated with human diseases remain largely unknown. In the present study, we observed an elevated lysine malonylation in a screening of seven lysine acylations in liver tissues of db/db mice, which is a typical model of type 2 diabetes. We also detected an elevated lysine malonylation in ob/ob mice, which is another model of type 2 diabetes. We then performed affinity enrichment coupled with proteomic analysis on liver tissues of both wild-type (wt) and db/db mice and identified a total of 573 malonylated lysine sites from 268 proteins. There were more malonylated lysine sites and proteins in db/db than in wt mice. Five proteins with elevated malonylation were verified by immunoprecipitation coupled with Western blot analysis. Bioinformatic analysis of the proteomic results revealed the enrichment of malonylated proteins in metabolic pathways, especially those involved in glucose and fatty acid metabolism. In addition, the biological role of lysine malonylation was validated in an enzyme of the glycolysis pathway. Together, our findings support a potential role of protein lysine malonylation in type 2 diabetes with possible implications for its therapy in the future.

Post-translational modifications (PTMs)1 have been recognized as a common feature of proteins (1–3). More than 300 types of PTMs have been identified according to the Swiss-Prot database (4, 5). Most of them use small molecular compounds as group donors. For example, adenosine-triphosphate (ATP) is used in phosphorylation, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) in methylation, and acetyl-CoA in acetylation. Lysine acylations including malonylation (6), succinylation (7), butyrylation (8), propionylation (9), and crotonylation (10) represent a group of PTMs that use intermediates of energy metabolism like malonyl-CoA, succinyl-CoA, butyryl-CoA, propionyl-CoA, and crotonyl-CoA as group donors. Among the lysine acylations, lysine malonylation was first identified in Escherichia coli (E. coli) and HeLa cells using a specific anti-Kmal (anti-malonyllysine) antibody (6). It was found in three proteins in E. coli and 17 proteins in HeLa cells. Using a novel chemical fluorescent probe, another group identified more than 300 malonylated protein candidates in HeLa cells (11). Despite the rapid progress in detection technologies and tools, functional studies of lysine malonylation and its role in human diseases have been lagging behind.

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by hyperglycemia and production of glycated proteins. For example, glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) has been clinically used as diagnostic criteria for diabetes. In addition to glycation, the role of other types of PTMs in type 2 diabetes remains to be revealed. In fact, elevated malonyl-CoA levels have been found in type 2 diabetic patients (12), and prediabetic rats (13). And hepatic overexpression of malonyl-CoA decarboxylase (MCD) decreased malonyl-CoA and reversed insulin resistance (14). Given the use of malonyl-CoA as malonyl donor in lysine malonylation, lysine malonylation is therefore anticipated to be of functional significance in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes.

In the present study, we observed elevated lysine malonylation in liver tissues of db/db mice after unbiased screening seven types of lysine acylations. We then detected elevated levels of lysine malonylation in liver tissues of more db/db and ob/ob mice. Using an immunoaffinity based proteomic method, we identified a total of 573 malonylated lysine sites from 268 proteins in liver tissues of wt and db/db mice. Elevation of lysine malonylation in five proteins was confirmed by immunoprecipitation coupled with Western blot analysis. Functional analysis of the malonylated proteins showed an apparent enrichment in metabolic pathways, especially those involved in the glucose and fatty acid metabolism. Our study indicates the putative association between protein lysine malonylation and type 2 diabetes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Anti-malonyllysine (PTM-901), anti-acetyllysine (PTM-105), anti-1,2-dimethyllysine (PTM-602), anti-succinyllysine (PTM-401), anti-butyryllysine (PTM-301), anti-propionyllysine (PTM-201), anti-crotonyllysine (PTM-502) antibodies, and anti-malonyllysine conjugated agarose beads were purchased from PTM Biolabs (Chicago, IL). G6PI (ab86950), LDHA (ab47010), FBP1 (ab109732), and 10-FTHFDH/ALDH1L1 (ab56777) antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Glutathione (GSH) agarose beads were purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Uppsala, Sweden). Sequencing-grade trypsin was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI), and C18 ZipTips were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). A list of other chemicals used for LC-MS/MS is available in previously published study (15).

Animals and Samples

C57 BLKS db/db mice (n = 5) and wt mice (n = 5) were provided by the Animal Center of Peking University. C57 BL/6J-ob/ob mice (n = 4) and wt mice (n = 4) were provided by the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, CAMS (Chinese Academy of Medical Science). Mouse studies were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee (Institute of Biophysics, CAS) and the National Health and Medical Research Council of China Guidelines on Animal Experimentation.

Tissue Lysate Preparation

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Tissues were homogenized in 1 ml lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS). The homogenized tissues were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm and the supernatant containing the tissue lysates was kept for later steps.

Western blotting and Coomassie Blue Staining

Western blot and Coomassie blue staining analysis were carried out as described previously (16).

In Vitro Malonylation Reaction and ALDOB Activity Assay

In vitro malonylation was performed as previously described (17). Briefly, FLAG-tagged ALDOB was overexpressed in 293T cells and purified using ANTI-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel (A2220, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as per instruction by the manufacturer. Purified ALDOB proteins were incubated for 12 h at 37 °C in buffer containing 1 mm malonyl-CoA, 50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, and 150 mm NaCl.

Enzymatic activity of ALDOB was determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the decrease of NADH at 340 nm in a coupled assay with triosephosphate isomerase (TPI) and glycerophosphate dehydrogenase (GDH) (18). Assays were performed in triplicates at 30 °C in buffer A (100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, and 1 mm EDTA) following addition of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate.

In-gel and In-solution Tryptic Digestion

For in-gel digestion, protein bands around 95 KDa, 55 KDa, 34 KDa, and 26 KDa were excised from the SDS-PAGE gels, cut into small pieces and destained using 50 mm triethyl ammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) in 40% acetonitrile. 100% acetonitrile was used to dehydrate the gel. 5 mm Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) was used to reduce the proteins. 10 mm methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS) was used to alkylate the proteins. Digestion was carried out using sequencing-grade modified trypsin (Promega) with a substrate ratio of 1:50 (w/w) overnight at 37 °C. Peptides were extracted with 60% acetonitrile and 5% formic acid (FA). Resulting peptides were dried and prepared for immunoprecipitation. For in-solution digestion, liver tissue lysates were precipitated with acetone and resolved in 8 m urea with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The samples were reduced and alkylated as done for in-gel digestion.

Affinity Enrichment of Malonylated Peptides

The tryptic peptides obtained from in-gel digestion or in-solution digestion were resolubilized in NETN buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 100 mm NaCl, and 1 mm EDTA). Anti-malonyllysine antibody-conjugated agarose beads were added and incubated at 4 °C for 12 h with gentle shaking. The beads were washed two times with NETN buffer, once with ETN buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl and 1 mm EDTA), and once with purified water. The bound peptides were eluted by 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and dried using the SpeedVac. The dried peptides were re-dissolved in 0.1% FA and desalted using C18 ZipTips.

Protein Identification and Quantification by LC-MS/MS

LC-MS/MS analyses were performed on a LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo, San Jose, CA) equipped with an Eksigent nanoLC system (Eksigent Technologies, LLC, Dublin, CA). The peptide mixtures were loaded onto 20-mm ReproSil-Pur C18-AQ (Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch) trapping columns (packed in-house, i.d., 150 μm; resin, 5 μm) and eluted into 150 mm ReproSil-Pur C18-AQ (Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch) analytical columns (packed in-house, i.d., 75 μm; resin, 3 μm) for MS analysis. Elution was achieved with a 0–35% gradient buffer B (Buffer A, 0.1% formic acid and 5% acetonitrile; Buffer B, 0.1% formic acid and 95% acetonitrile) over 90 min using a data-dependent method. All MS/MS spectra were collected using normalized collision energy (setting, 35%), an isolation window of 3 m/z, and one micro-scan. The acquired MS/MS spectra were searched using the Mascot (v2.3.2) search engine in the Proteome Discoverer™ Software (v1.3, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) against the mouse Uniprot database (version 2.3, 50,807 sequences) using a target-decoy database searching strategy (19). The following search criteria were employed: three missed cleavages were allowed; mass tolerance for parent ions was set to 20 ppm; mass tolerance for fragment ions was set to 0.8 Da; minimum peptide length was set at 6; Cys (+45.9877 Da, methanethiosulfonate, MMTS) was set as a fixed modification; Met (+15.9949 Da, oxidation) and Lys (+86.0004 Da, malonylation) were considered as variable modifications. The global false discovery rate (FDR) for both peptides and proteins was set to 0.01. The relative quantitation of proteins between two samples (wt versus db/db mice) was achieved by extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) of peptides with a Mascot score of ≥25 that ranked first. The resulting peptides were extracted using the Precursor Ion Area Detector feature in the Proteome Discoverer program (version 1.3), using a mass tolerance of 3 ppm. Only proteins with a minimum of two quantifiable peptides were included in our final data set. The peptides did not match any proteins present in the Uniprot database, and peptides with no XICs in both wt and db/db mice were excluded from the final data set.

Bioinformatics Analysis of Malonylated Proteins

The malonylated proteins were classified based on the PANTHER (Protein Analysis through Evolutionary Relationships) system. The DAVID 6.7 was employed for enrichment analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. The default mouse proteome was used as the background list. The significance of the obtained enrichments was evaluated by using the Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p value. The identified proteins with lysine malonylation were searched against the STRING database (V 9.1) for protein–protein interactions. A network of protein–protein interactions was generated, which was then visualized using the Cytoscape program (v3.0.2). This interaction network was further analyzed for densely connected regions using the program “Molecular Complex Detection” (MCODE).

RESULTS

Protein Lysine Malonylation Elevate in Liver Tissues of db/db and ob/ob Mice

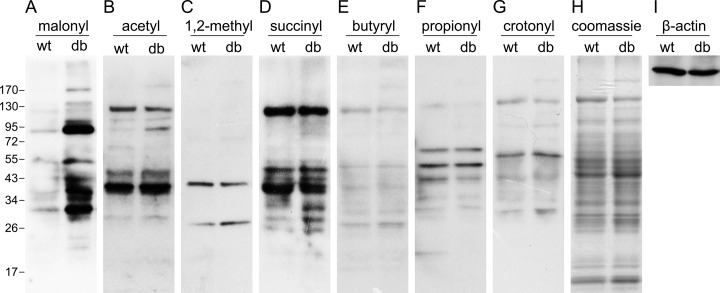

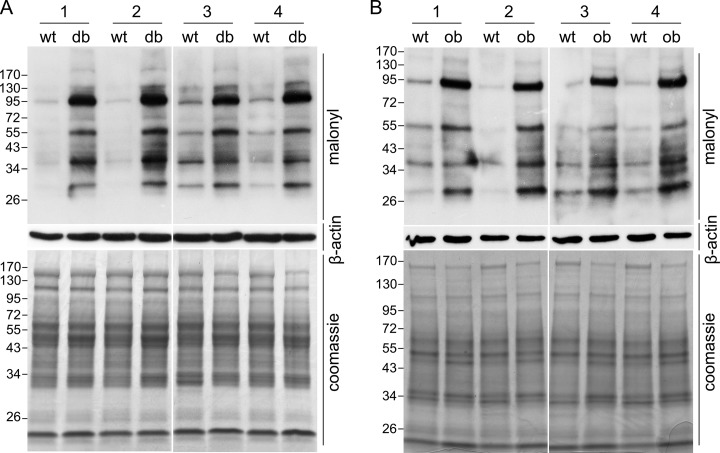

The db/db mice, which has a homozygous point mutation in the db gene encoding for the leptin receptor, is an classical type 2 diabetic mouse model (20, 21). To investigate the role of protein lysine acylations in type 2 diabetes, seven types of lysine acylations were investigated by Western blot in liver tissue lysates of wt and db/db mice. A marked elevation of lysine malonylation was observed in db/db mice relative to wild type littermates (Fig. 1A), while little elevation of lysine acetylation, 1, 2-methylation, succinylation, butyrylation, propionylation, and crotonylation was detected (Fig. 1B–1G). Equal loading was verified by β-actin Western blot and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 1H, I). Furthermore, we detected lysine malonylation in another four wt and db/db mice and observed a significant increase in lysine malonylation in liver tissues of all db/db mice (Fig. 2A). To investigate whether lysine malonylation levels are elevated beyond wt levels in other type 2 diabetic animal models as well, we tested lysine malonylation levels in ob/ob mice. Consistent with the observations in db/db mice, an elevated levels of lysine malonylation was detected in liver tissues of all ob/ob mice relative to wt mice (Fig. 2B). Together, these findings demonstrated that lysine malonylation was elevated in liver tissues of db/db and ob/ob type 2 diabetic animal models.

Fig. 1.

Detection of seven lysine acylations in the liver of wt and db/db mice. Western blot analysis of liver tissue lysates from wt and db/db (db) mice by the antibody indicated. A, malonyl: anti-malonyllysine; B, acetyl: anti-acetyllysine; C, 1, 2-methyl: anti-mono-, dimethyllysine; D, succinyl: anti-succinyllysine; E, butyryl: anti-butyryllysine; F, propionyl: anti-propionyllysine; G, crotonyl: anti-crotonyllysine; H–I, The loading is controlled by β-actin and coomassie blue staining.

Fig. 2.

Detection of lysine malonylation in liver of four db/db and ob/ob mice. Western blot analysis of liver tissue lysates from four db/db (db) A, and ob/ob (ob) B, mice and their counterpart wt mice by anti-malonyllysine antibody. Equal loading was verified using β-actin Western blot and Coomassie blue staining.

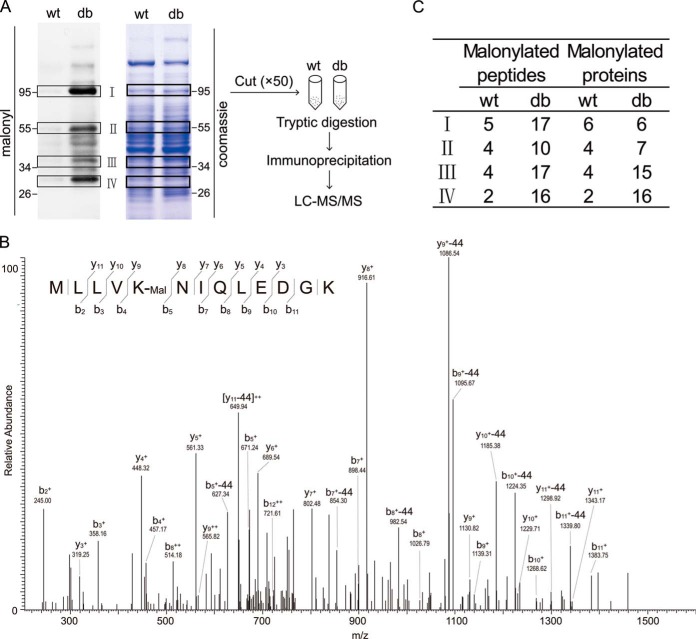

Identification of Malonylated Proteins in Gels

To validate the increase of protein lysine malonylation and identify the malonylated lysine sites and proteins, liver lysates from three wt or db/db mice were combined and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Four gel bands with the highest levels of lysine malonylation were cut and trypsin-digested (Fig. 3A). For analysis of each band, a total of 50 gels were cut and combined. The digested peptides were immunoprecipitated with anti-malonyllysine antibody-conjugated agarose beads and then loaded onto LC-MS/MS. One representative MS/MS spectrum of the identified malonylated peptides is shown in Fig. 3B. There was a neutral loss of carbon dioxide (CO2, 44 Da), which was used for confirming the presence of lysine malonylation. The LC-MS/MS results showed that the number of malonylated proteins and peptides identified for each of the four bands was higher in db/db mice relative to wt (Fig. 3C). Detailed information on all malonylated proteins and peptides identified is summarized in supplemental Table S1. Together, our results indicated that proteins from the livers of db/db mice were more intensively malonylated than those in wt, which was consistent with the results obtained from Western blot analysis.

Fig. 3.

Identification of protein lysine malonylation by in-gel digestion and LC-MS/MS. A, Diagram of in-gel digestion coupled with LC-MS/MS analysis. Four pairs of bands in Coomassie blue stained gel, which showed great increased levels of lysine malonylation by Western blot, were cut and trypsin-digested in-gel. Digested peptides were extracted and immunoprecipitated using anti-malonyllysine antibody-conjugated agarose beads. Immunoprecipitated peptides were identified by LC-MS/MS. ×50: a total of 50 gels were cut for each bands. B, A representative MS/MS spectra of malonated peptides. The neutral loss of 44KDa is unique signature of malonylation and designated as “−44.” C, Number of malonylated proteins and peptides detected for each band.

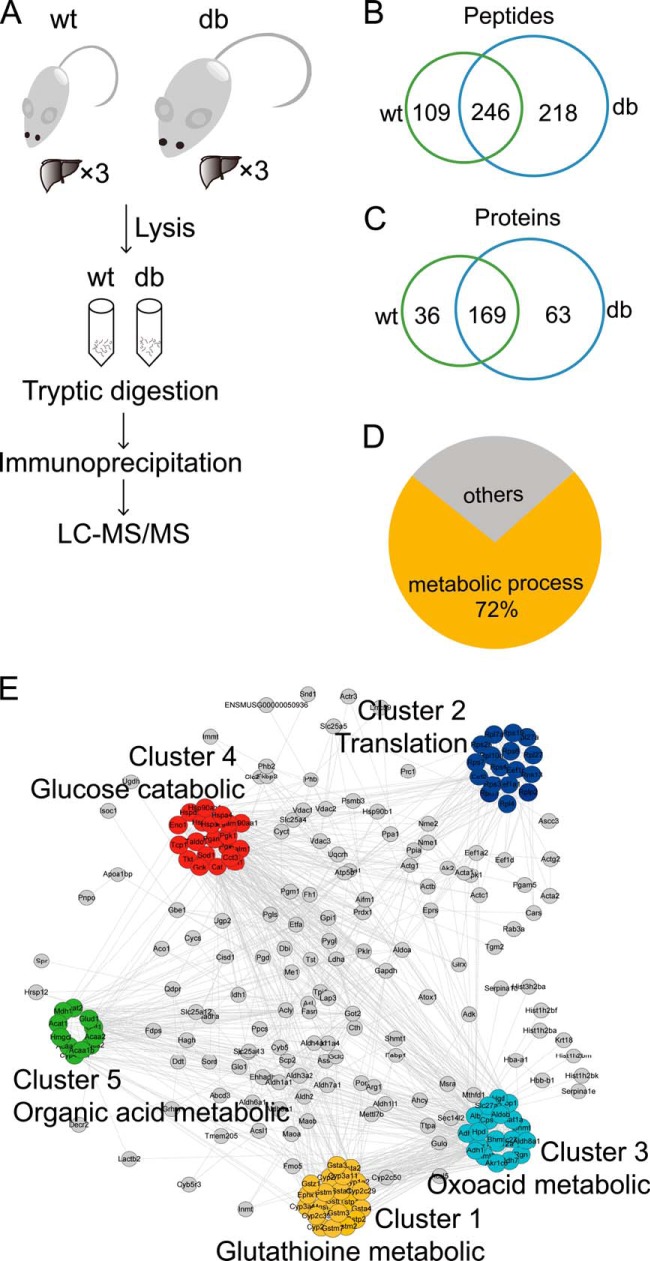

Identification of Malonylated Proteins in Solution

Having successfully tested the ability of our LC-MS/MS method to detect malonylation, we used in-solution tryptic digestion to widen the scope of our analysis and identify lysine malonylation in a larger number of peptides (Fig. 4A). Liver lysates were combined from either three wt or three db/db mice, then trypsin-digested and immunoprecipitated using anti-malonyllysine-conjugated agarose beads. After immunoprecipitation, LC-MS/MS, and a search against the mouse Uniprot database, we identified a total of 268 Uniprot-reviewed proteins, containing 573 malonylated lysine sites (supplemental Table S2). There were 246 lysine malonylation sites that overlapped between wt and db/db mice (Fig. 4B); and 169 malonylated proteins that overlapped between the two groups (Fig. 4C). We extracted ion chromatograms and calculated the area under the peak associated with malonylated peptides, which indirectly reflects the quantity of each malonylated peptide. For the 246 overlapping peptides, the average under-the-curve area of extracted ion chromatograms for each malonylated peptides in db/db was larger than that in the wt mice (supplemental Fig. S1). Together, these results suggested greater malonylation in db/db livers relative to wt, and were consistent with the results obtained by Western blot and in-gel identification.

Fig. 4.

Proteomic identification and bioinformatics analysis of protein lysine malonylation. A, Diagram of in-solution digestion coupled with LC-MS/MS analysis. Liver tissues from wt and db/db (db) mice were lysed. Proteins were extracted, trysin-digested, immunoprecipitated using anti-malonyllysine antibody-conjugated agarose beads, and detected by LC-MS/MS. ×3: livers tissues from three mice were combined. B, Venn diagram showing overlapped malonylated peptides between wt and db. C, Venn diagram showing overlapped malonylated proteins between wt and db. D, Pie diagram showing biological process enrichment of total malonylated proteins. Analysis was done with the web tool “PANTHER.” E, Network diagram showing interactions between malonylated proteins extracted from STRING database. MCODE method was used to calculate clusters. Five clusters were identified.

We compared the 268 malonylated proteins in the mouse liver with two previously acquired malonylation data sets in the HeLa cell line by manually searching for protein homologs. Our data contained 13 malonylated proteins out of 17 proteins identified by Zhao et al. and 54 malonylated protein candidates out of the 375 proteins identified by Li et al. (supplemental Table S3) (6, 11). Thus, the overlap observed between these data sets confirmed the validity of our experimental procedures and results. We then compared our data with a large-scale succinylation data set, and 135 out of 433 Uniprot-reviewed proteins were shown to overlap between the two data sets (supplemental Table S3) (22). These results suggested that malonylation and succinylation might occur at identical proteins.

Our data also revealed that some proteins were highly malonylated. For example, 29 malonylated peptides (19 unique malonylated lysine sites) were identified in the one-carbon metabolic enzyme 10-FTHFDH. The proteins with more than five malonylated peptides are summarized in supplemental Table S4.

Biological Process Analysis of Malonylated Proteins

To evaluate the biological relevance of lysine malonylation, the PANTHER classification system was used to sort the malonylated proteins according to their associated biological processes (23). The results of this analysis showed that 194 out of 268 malonylated proteins (72%) were classified as involved in a metabolic process (Fig. 4D and supplemental Table S5). The analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) terms by the Functional Annotation Tool of DAVID also revealed that most of the enriched GO terms were involved in catabolic or metabolic processes (supplemental Table S5) (24).

Protein Interaction Network Analysis of Malonylated Proteins

To better understand the function of lysine malonylation, the malonylated proteins were subjected to a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis using the STRING database (25). A PPI network containing 239 nodes and 1517 edges were constructed. To characterize protein complexes among the malonylated proteins, the PPI networks was analyzed for highly connected nodes by MCODE (26). Five highly connected clusters have been identified including the glutathione metabolic, oxoacid metabolic, organic acid metabolic, glucose catabolic, and translation cluster (Fig. 4E). The PPI network analysis indicated that lysine malonylation occurs in various metabolic complexes.

KEGG Pathway Analysis of Malonylated Proteins

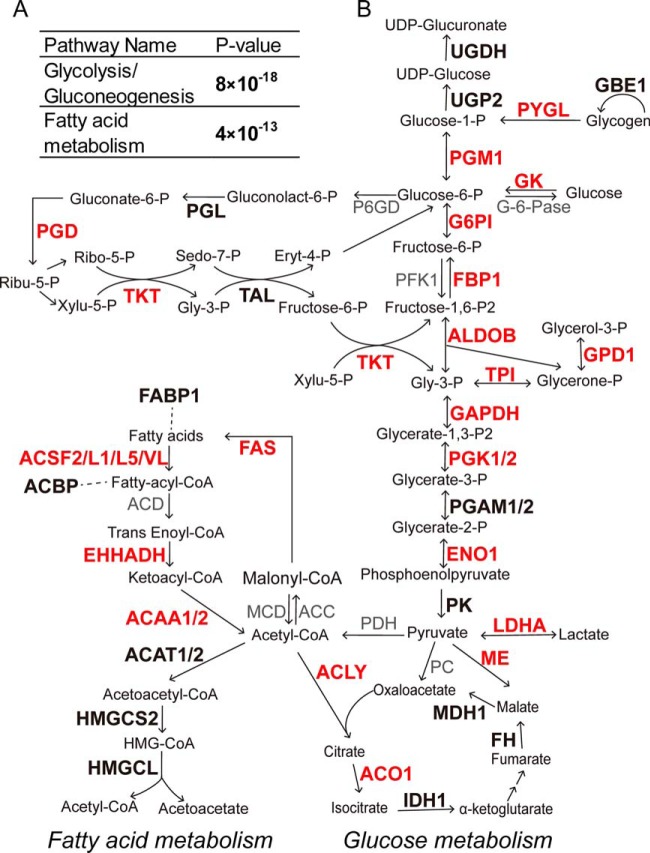

To further characterize the role of lysine malonylation, KEGG pathway analysis was performed for the malonylated proteins. The results showed that malonylated proteins were enriched in the glucose, fatty acid, and amino acid metabolic pathways (supplemental Table S5 and Fig. 5A). Disorders of glucose and fatty acid metabolism are two major features of type 2 diabetes. The majority of enzymes involved in glucose and fatty acid metabolism were identified to be malonylated in livers of db/db mice (Fig. 5B and supplemental Table S2). Indeed, many of the enzymes identified showed elevated levels of lysine malonylation (supplemental Table S6). Dysfunction of glucose metabolic enzymes, including glucokinase (27, 28), glucose-6-phosphatase (29, 30), phosphofructokinase (31), and glycogen phosphorylase (32), is known to be involved in type 2 diabetes. Although the role of lysine malonylation in dysfunction of metabolic enzymes remains unknown, the high levels of lysine malonylation on metabolic enzymes in db/db livers indicates an association between lysine malonylation and metabolic disorders of type 2 diabetes.

Fig. 5.

Malonylated proteins in glucose and fatty acid metabolism pathways. A, Enrichment of malonylated proteins in Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis and Fatty acid metabolism pathways according to KEGG pathway analysis. B, Diagram of glucose and fatty acid metabolic pathways. Bold: proteins with at least one malonylated lysine sites in wt or db/db mice. Red: proteins with elevated lysine malonylation in db/db mice. Detailed protein and peptides information in supplemental Tables S2 and S6. Arrows: reaction directions. Dashed line: interaction relationship.

Verification of Lysine Malonylation by Immunoprecipitation Coupled with Western blot Analysis

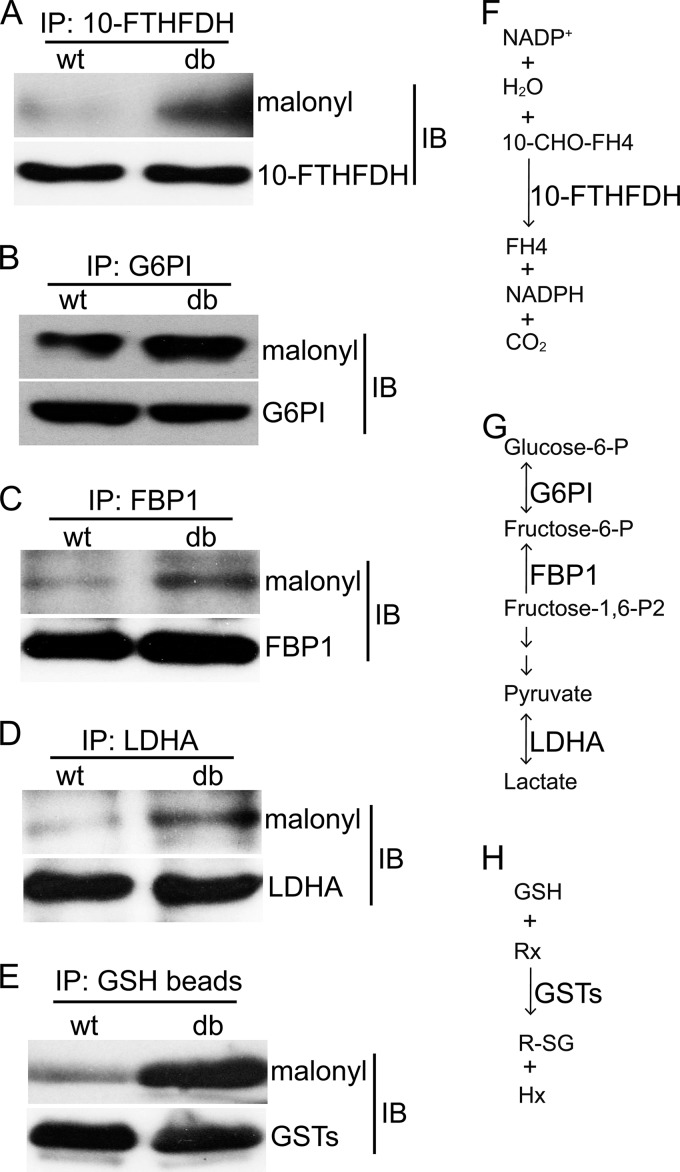

To verify the LC-MS/MS results, we selected four proteins (10-FTHFDH, G6PI, FBP1, and LDHA) with commercially available antibodies for immunoprecipitation analysis. After immunoprecipitating an equal amount of proteins from wt and db/db samples, lysine malonylation was detected by Western blot. Consistent with the LC-MS/MS results, levels of lysine malonylation of 10-FTHFDH, G6PI, FBP1, and LDHA proteins were elevated in db/db livers relative to wt (Fig. 6A–6D). 10-FTHFDH is known to catalyze the transformation of 10-CHO-FH4 to FH4 (Fig. 6F), whereas G6PI, FBP1, and LDHA are important enzymes in glucose metabolism (Fig. 6G). In addition, GSTs, which catalyze the conjugation of glutathione (GSH) with electrophilic compounds, were affinity-purified using GSH-beads (Fig. 6H). Elevated lysine malonylation of GSTs in db/db mice was detected by Western blot analysis (Fig. 6E). Overall, these results verified the elevated levels of lysine malonylation observed for some of the proteins identified by LC-MS/MS.

Fig. 6.

Verification of increased lysine malonylation in db/db mice. Four proteins that showed increased lysine malonylation by LC-MS/MS method and with commercially available antibody available for immunoprecipitation were selected. Tissue lysates were immunoprecipitated by the selected antibodies and protein-A agarose beads. For GSTs, tissue lysates were directly immunoprecipitated by GSH-beads. Efficiency of immunoprecipitation and malonylation status of target proteins were evaluated by Western blot analysis. A, 10-FTHFDH (10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase). B, G6PI (Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase). C, FBP1 (Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 1). D, LDHA (l-lactate dehydrogenase A chain). E, GSTs (Glutathione S-transferases). F–H, Diagram of reactions involving the indicate proteins. 10-CHO-FH4 (10-formyltetrahydrofolate), FH4 (tetrahydrofolate).

Impact of Lysine Malonylation on Enzymatic Activity of ALDOB (Fructose bisphosphate aldolase B)

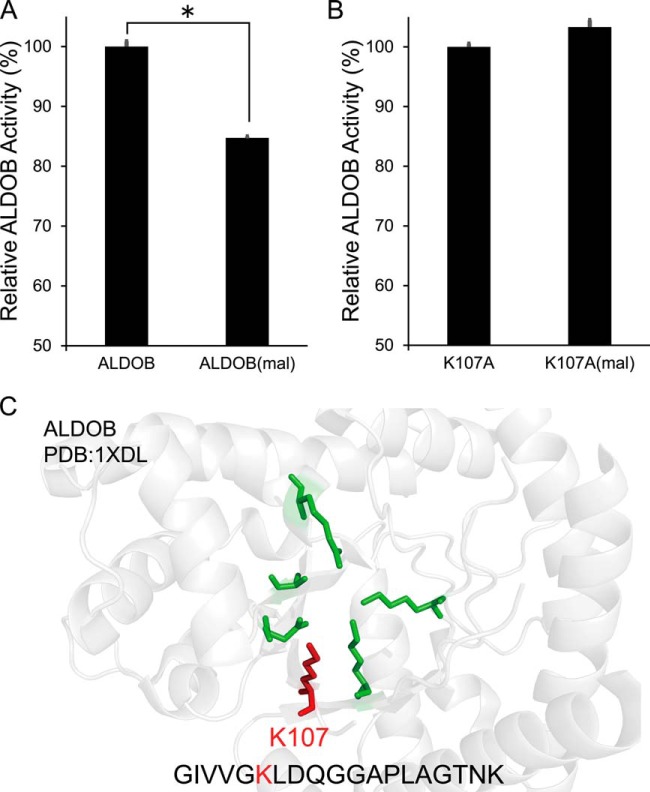

To validate the biological role of lysine malonylation, we searched the PDB database and found that malonylation can occur on key residues of several enzymes, including K107 on ALDOB, K124 on ACAT1 (Acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase), K46 and K273 on HMGCS2 (Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, mitochondrial), and K279 and K345 on PBE (Peroxisomal bifunctional enzyme) (Fig. 7C and supplemental Fig. S4). To evaluate the influence of malonylation on their enzymatic activity, we selected ALDOB for further analysis. We purified wild type ALDOB and K107A-mutated ALDOB proteins and determined their enzymatic activity spectrophotometrically. We found that enzymatic activity of K107A-mutated ALDOB decreased 30% comparing with ALDOB (supplemental Fig. S5). The results reveals the importance of K107 for ALDOB activity. We next analyzed the influence of K107 malonylation on ALDOB activity. Because of lack of a site-specific malonyltransferase, we were not able to obtain K107-specific malonylated ALDOB. Alternatively, we nonspecifically malonylated purified ALDOB proteins by an in vitro reaction. We found that purified ALDOB was extensively malonylated in vitro, and that enzymatic activity of malonylated ALDOB decreased by 20% relative to nonmalonylated ALDOB (Fig. 7A). However, enzymatic activity of malonylated K107A-mutated ALDOB decreased little comparing with K107A-mutated ALDOB (Fig. 7B). Altogether, the body of evidence obtained in our studies indicates that K107 malonylation plays an important role in the regulation of ALDOB activity.

Fig. 7.

Detection of ALDOB activity after malonylation of ALDOB and lysine 107 mutated ALDOB (K107A). Change of ALDOB A, and K107A B, activity after in vitro malonylation reaction. ALODB and K107A were purified from HEK293T cells and incubate at 30 °C with NADH. Activity were determined by measuring decrease of absorbance at 340 nm. p value were calculated based on triplicate measurements. (*: p value < 0.01, t test). C, Structure analysis of mammalian ALDOB protein. The catalytic center contains several key residues including lysine 107 (red). The peptides with lysine malonylation (red color K) identified by MS/MS are indicated at the bottom.

DISCUSSION

In our study, we analyzed acylation patterns in wt and type 2 diabetic mice. We identified an elevation of protein lysine malonylation levels in liver tissues of db/db and ob/ob type 2 diabetic animal models, and identified large numbers of malonylated proteins in liver tissues of db/db mice. Bioinformatics analysis of the malonylated proteins indicated a role in glucose and fatty acid metabolism as their predominant function. In addition to liver, we also observed the status of lysine malonylation in other tissues and found that elevation of lysine malonylation was liver-specific (supplemental Fig. S2). In addition to db/db and ob/ob mice, we measured lysine malonylation in other type 2 diabetic animal models including KK mice, ob/ob rats, and spontaneously type 2 diabetic monkeys and found elevation of lysine malonylation to various degrees (supplemental Fig. S3). Thus, we hypothesize that liver-specific elevation of lysine malonylation might be common in type 2 diabetes.

Elevation of lysine malonylation is consistent with previous studies reporting higher malonyl-CoA levels in type 2 diabetes (12, 13). Because lysine malonylation requires malonyl-CoA, the biological function of malonyl-CoA might indirectly reflect the biological role of lysine malonylation. Malonyl-transferase(s) and demalonylase(s) are also required for lysine malonylation. SIRT5 has been identified as a demalonylase (6). However, knockdown of SIRT5 only raises lysine malonylation moderately, whereas it results in a marked increase in overall succinylation levels, suggesting the existence of other, as yet unidentified demalonylases (33). In addition, SIRT5 does not appear to be associated with type 2 diabetes and SIRT5 deficiency fails to lead to any phenotypes resembling type 2 diabetes (33). Future work in this field would have to include the identification of the unknown malonyl-transferase(s) and alternative demalonylase(s), together with the evaluation of their role in type 2 diabetes.

Similar to lysine malonylation, lysine acetylation has been found in almost every enzyme involved in glucose and fatty acid metabolism (34). Acetylation of metabolic enzymes is known to have a great impact on their catalytic functions (34). Acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA are closely related and inter-convertible, and therefore we propose that lysine malonylation also functions in regulating metabolism. In fact, malonylation can occur on key residues of metabolic enzymes (Fig. 7A and supplemental Fig. S4). Malonylation of ALDOB in vitro has been shown to decrease its activity (Fig. 7B). Malonylation of other proteins probably affect their functions. The following focus in the field would be on studying malonylation of several important type 2 diabetic associated proteins.

Analysis of identified malonylated proteins revealed the role of malonylation in metabolic processes. Our malonylation data mirror earlier proteomic results for acetylation and succinylation, which demonstrated an enrichment of acetylation and succinylation in metabolic enzymes (22, 34). Metabolic intermediates serve as group donors of protein acylations and protein acylations in turn regulate the production of metabolic intermediates. This might be a general feedback mechanism used in cells to control metabolism in a highly efficient manner. Given their potential role in metabolic regulation, acylations might contribute to different pathological processes. Although malonylation might dominate in metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes, other acylations might be more important in other metabolic diseases such as coronary heart disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Recently, elevation of lysine acetylation has been detected in the kidneys of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats (35). In addition, lysine glutarylation has been associated with the disease of glutaric academia (36). Altogether, our work identified a large number of malonylated proteins, which are potential important in regulating metabolism in type 2 diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Peng Li (Tsinghua University, China) for providing liver samples of ob/ob mice. We also thank Dr. Junjie Hou (Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for excellent technical assistance and Dr. Torsten Juelich (Peking University, China) for critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Y.D. and T.W. designed research; Y.D., T.C., P.X., B.Z., X.H., and P.W. performed research; Y.D., T.C., T.L., P.L., F.Y., and T.W. analyzed data; Y.D. and T.W. wrote the paper.

* This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (Nos. 2010CB833700, 2012CB934003, 2012CB966803, and 2014CBA02003), the Major Equipment Program of China (No. 2011YQ030134), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31100614, 31400666), and the National Laboratory of Biomacromolecules.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 to S5 and Tables S1 to S6.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 to S5 and Tables S1 to S6.

Author Contributions: Y. D. and T. W. designed the study, collected the data, and wrote the manuscript. T. C., T. L., P. X., B. Z., X. H., and P. W. collected the data. P. L. and F. Y. contributed to discussion and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation and approved the final manuscript. T. W. and F. Y. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- PTM

- post-translational modifications

- 10-FTHFDH

- 10-Formyltetrahydrofolate Dehydrogenase

- ACAT1

- Acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase

- ALDOB

- fructose bisphosphate aldolase B

- FBP1

- fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 1

- G6PI

- glucose-6-phosphate isomerase

- GSTs

- glutathione S-transferases

- HbA1c

- haemoglobin A1c

- HMGCS2

- Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, mitochondrial

- LDHA

- lactate dehydrogenase A

- MCD

- malonyl-CoA decarboxylase

- PBE

- Peroxisomal bifunctional enzyme

- SAM

- S-adenosylmethionine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nussinov R., Tsai C. J., Xin F., Radivojac P. (2012) Allosteric post-translational modification codes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 447–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walsh C. T., Garneau-Tsodikova S., Gatto G. J., Jr. (2005) Protein posttranslational modifications: the chemistry of proteome diversifications. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 44, 7342–7372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strahl B. D., Allis C. D. (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403, 41–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lu C. T., Huang K. Y., Su M. G., Lee T. Y., Bretana N. A., Chang W. C., Chen Y. J., Chen Y. J., Huang H. D. (2013) DbPTM 3.0: an informative resource for investigating substrate site specificity and functional association of protein post-translational modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D295–D305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khoury G. A., Baliban R. C., Floudas C. A. (2011) Proteome-wide post-translational modification statistics: frequency analysis and curation of the swiss-prot database. Sci. Rep. 1, 90 DOI: 10.1038/srep00090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peng C., Lu Z., Xie Z., Cheng Z., Chen Y., Tan M., Luo H., Zhang Y., He W., Yang K., Zwaans B. M., Tishkoff D., Ho L., Lombard D., He T. C., Dai J., Verdin E., Ye Y., Zhao Y. (2011) The first identification of lysine malonylation substrates and its regulatory enzyme. Mol. Cell Proteomics 10, M111 012658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Z., Tan M., Xie Z., Dai L., Chen Y., Zhao Y. (2011) Identification of lysine succinylation as a new post-translational modification. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 58–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen Y., Sprung R., Tang Y., Ball H., Sangras B., Kim S. C., Falck J. R., Peng J., Gu W., Zhao Y. (2007) Lysine propionylation and butyrylation are novel post-translational modifications in histones. Mol. Cell Proteomics 6, 812–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng Z., Tang Y., Chen Y., Kim S., Liu H., Li S. S., Gu W., Zhao Y. (2009) Molecular characterization of propionyllysines in nonhistone proteins. Mol. Cell Proteomics 8, 45–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tan M., Luo H., Lee S., Jin F., Yang J. S., Montellier E., Buchou T., Cheng Z., Rousseaux S., Rajagopal N., Lu Z., Ye Z., Zhu Q., Wysocka J., Ye Y., Khochbin S., Ren B., Zhao Y. (2011) Identification of 67 histone marks and histone lysine crotonylation as a new type of histone modification. Cell 146, 1016–1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bao X., Zhao Q., Yang T., Fung Y. M., Li X. D. (2013) A chemical probe for lysine malonylation. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52, 4883–4886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bandyopadhyay G. K., Yu J. G., Ofrecio J., Olefsky J. M. (2006) Increased malonyl-CoA levels in muscle from obese and type 2 diabetic subjects lead to decreased fatty acid oxidation and increased lipogenesis; thiazolidinedione treatment reverses these defects. Diabetes 55, 2277–2285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao Z., Lee Y. J., Kim S. K., Kim H. J., Shim W. S., Ahn C. W., Lee H. C., Cha B. S., Ma Z. A. (2009) Rosiglitazone and fenofibrate improve insulin sensitivity of pre-diabetic OLETF rats by reducing malonyl-CoA levels in the liver and skeletal muscle. Life Sci. 84, 688–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. An J., Muoio D. M., Shiota M., Fujimoto Y., Cline G. W., Shulman G. I., Koves T. R., Stevens R., Millington D., Newgard C. B. (2004) Hepatic expression of malonyl-CoA decarboxylase reverses muscle, liver, and whole-animal insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 10, 268–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen X., Cui Z., Wei S., Hou J., Xie Z., Peng X., Li J., Cai T., Hang H., Yang F. (2013) Chronic high glucose induced INS-1beta cell mitochondrial dysfunction: a comparative mitochondrial proteome with SILAC. Proteomics 13, 3030–3039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiang P., Huang Z., Zhao H., Wei T. (2013) Hydrogen peroxide impairs autophagic flux in a cell model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 433, 408–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wagner G. R., Payne R. M. (2013) Widespread and enzyme-independent Nepsilon-acetylation and Nepsilon-succinylation of proteins in the chemical conditions of the mitochondrial matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 29036–29045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Santamaria R., Esposito G., Vitagliano L., Race V., Paglionico I., Zancan L., Zagari A., Salvatore F. (2000) Functional and molecular modeling studies of two hereditary fructose intolerance-causing mutations at arginine 303 in human liver aldolase. Biochem. J. 350, 823–828 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Elias J. E., Gygi S. P. (2007) Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 4, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coleman D. L. (1982) Diabetes-obesity syndromes in mice. Diabetes 31, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hummel K. P., Dickie M. M., Coleman D. L. (1966) Diabetes, a new mutation in the mouse. Science 153, 1127–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Park J., Chen Y., Tishkoff D. X., Peng C., Tan M., Dai L., Xie Z., Zhang Y., Zwaans B. M., Skinner M. E., Lombard D. B., Zhao Y. (2013) SIRT5-mediated lysine desuccinylation impacts diverse metabolic pathways. Mol. Cell 50, 919–930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mi H., Muruganujan A., Casagrande J. T., Thomas P. D. (2013) Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1551–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang da W., Sherman B. T., Lempicki R. A. (2009) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 4, 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Franceschini A., Szklarczyk D., Frankild S., Kuhn M., Simonovic M., Roth A., Lin J., Minguez P., Bork P., von Mering C., Jensen L. J. (2013) STRING v9.1: protein–protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D808–D815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bader G. D., Hogue C. W. (2003) An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics 4, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glaser B., Kesavan P., Heyman M., Davis E., Cuesta A., Buchs A., Stanley C. A., Thornton P. S., Permutt M. A., Matschinsky F. M., Herold K. C. (1998) Familial hyperinsulinism caused by an activating glucokinase mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 338, 226–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Froguel P., Vaxillaire M., Sun F., Velho G., Zouali H., Butel M. O., Lesage S., Vionnet N., Clement K., Fougerousse F., Tanizawa Y., Weissenbach J., Beckmann J. S., Lathrop G. M., Passa P., Permutt M. A., Cohen D. (1992) Close linkage of glucokinase locus on chromosome 7p to early-onset non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Nature 356, 162–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Clore J. N., Stillman J., Sugerman H. (2000) Glucose-6-phosphatase flux in vitro is increased in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 49, 969–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Massillon D., Barzilai N., Hawkins M., Prus-Wertheimer D., Rossetti L. (1997) Induction of hepatic glucose-6-phosphatase gene expression by lipid infusion. Diabetes 46, 153–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ristow M., Vorgerd M., Mohlig M., Schatz H., Pfeiffer A. (1997) Deficiency of phosphofructo-1-kinase/muscle subtype in humans impairs insulin secretion and causes insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 2833–2841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin W. H., Hoover D. J., Armento S. J., Stock I. A., McPherson R. K., Danley D. E., Stevenson R. W., Barrett E. J., Treadway J. L. (1998) Discovery of a human liver glycogen phosphorylase inhibitor that lowers blood glucose in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 1776–1781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yu J., Sadhukhan S., Noriega L. G., Moullan N., He B., Weiss R. S., Lin H., Schoonjans K., Auwerx J. (2013) Metabolic characterization of a Sirt5 deficient mouse model. Sci. Rep. 3, 2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao S., Xu W., Jiang W., Yu W., Lin Y., Zhang T., Yao J., Zhou L., Zeng Y., Li H., Li Y., Shi J., An W., Hancock S. M., He F., Qin L., Chin J., Yang P., Chen X., Lei Q., Xiong Y., Guan K. L. (2010) Regulation of cellular metabolism by protein lysine acetylation. Science 327, 1000–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kosanam H., Thai K., Zhang Y., Advani A., Connelly K. A., Diamandis E. P., Gilbert R. E. (2014) Diabetes induces lysine acetylation of intermediary metabolism enzymes in the kidney. Diabetes 63, 2432–2439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tan M., Peng C., Anderson K. A., Chhoy P., Xie Z., Dai L., Park J., Chen Y., Huang H., Zhang Y., Ro J., Wagner G. R., Green M. F., Madsen A. S., Schmiesing J., Peterson B. S., Xu G., Ilkayeva O. R., Muehlbauer M. J., Braulke T., Muhlhausen C., Backos D. S., Olsen C. A., McGuire P. J., Pletcher S. D., Lombard D. B., Hirschey M. D., Zhao Y. (2014) Lysine glutarylation is a protein post-translational modification regulated by SIRT5. Cell Metab. 19, 605–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.