Abstract

Evidence suggests that parenting attitudes are transmitted within families. However, limited research has examined this prospectively. The current prospective study examined direct effects of early maternal attitudes toward parenting (as measured at child age 4 by the Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory [AAPI]) on later youth parenting attitudes (as measured by the AAPI at youth age 18). Indirect effects via child maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, and emotional maltreatment), parent involvement, and youth functioning (internalizing and externalizing problems) were also assessed. Analyses were conducted on data from 412 families enrolled in the Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN). There were significant direct effects for three of the four classes of mother parenting attitudes (appropriate developmental expectations of children, empathy toward children, and appropriate family roles) on youth attitudes but not for rejection of punishment. In addition, the following indirect effects were obtained: Mother expectations influenced youth expectations via neglect; mother empathy influenced youth empathy via both parental involvement and youth externalizing problems; and mother rejection of punishment influenced youth rejection of punishment via youth internalizing problems. None of the child or family process variables, however, affected the link between mother and youth attitudes about roles.

Keywords: parenting attitudes, maltreatment, youth adjustment

The transition to parenting is one of the key developmental tasks of emerging adulthood for most young people (Azar, 2003), and it is important to understand the factors that predict positive transitions to parenting. Even if parenting occurs later in life, attitudes toward parenting appear to be most in flux in emerging adulthood (Azar, 2003). These attitudes in turn are likely to predict parental behavior and effective parenting, regardless of the timing of parenting (Grusec, 2008). Thus, it is important to understand the factors that determine parenting attitudes in emerging adults universally but perhaps particularly in those with early adverse experiences, including maltreatment. By definition, youth with a history of maltreatment have experienced inconsistent and often confusing models of parenting that perhaps have not been unambiguously positive or negative (Caldwell, Shaver, Li, & Minzenberg, 2011). This article prospectively examines continuities between youth and mother attitudes toward parenting, and the roles of maltreatment, other parenting behavior, and youth functioning, in explaining these links.

Parenting Attitudes

Because parenting attitudes are a central determinant of parenting behavior and may reflect more general socioemotional capacities, the formation of these attitudes is considered a key developmental task of early/emerging adulthood (Azar, 2003). Such parenting attitudes are especially relevant to emerging adult well-being and the transition to parenting (see Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000; Holden & Buck, 2002; Sigel & McGillicuddy-DeLisi, 2002). This is because expectations for child behavior have been shown to influence the initiation and maintenance of specific parenting behaviors which, in turn, predict child adjustment (e.g., Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003). It is also critical to recognize that attitudes about appropriate parenting practices are multidimensional and may include (1) parents’ expectations around child behavior and roles within the family and the degree to which these expectations are consonant with developmental capacities (Bugental & Johnson, 2000; Sigel & McGillicuddy-DeLisi, 2002); (2) the weight given to child autonomy and control (Bugental & Johnson, 2000); (3) beliefs about the appropriate means of discipline and asserting parental control (Bugental & Johnston, 2000); and (4) ability to take the child’s perspective in a developmentally appropriate way (Sigel & McGillicuddy-DeLisi, 2002).

Intergenerational Aspects of Parenting Attitudes

Individuals are likely first exposed to expectations for and appropriate parental responses to child behavior within the family context (Barnett, Shanahan, Deng, Haskett, & Cox, 2010; Bornstein, 2005; Kim, Trickett, & Putnam, 2010; Locke & Newcomb, 2004; Lunkenheimer, Kittler, Olson, & Kleinberg, 2006). Implicit in this notion is that there should be a relatively strong link between parenting attitudes of parents and the subsequent attitudes of children as they enter adulthood. Such links may be transmitted both implicitly from experiences and explicitly from beliefs around parenting within the context of the family of origin and to result, in turn, in habitual ways of thinking about parenting and child behavior (Waller, Gardner, Dishion, Shaw, & Wilson, 2012). In this article, we examine several intervening variables that may account for transmission of parenting attitudes between mothers and their children. We focus on mothers in particular because mothers remain the primary caretakers of children even in two-parent homes (Craig & Mullan, 2011).

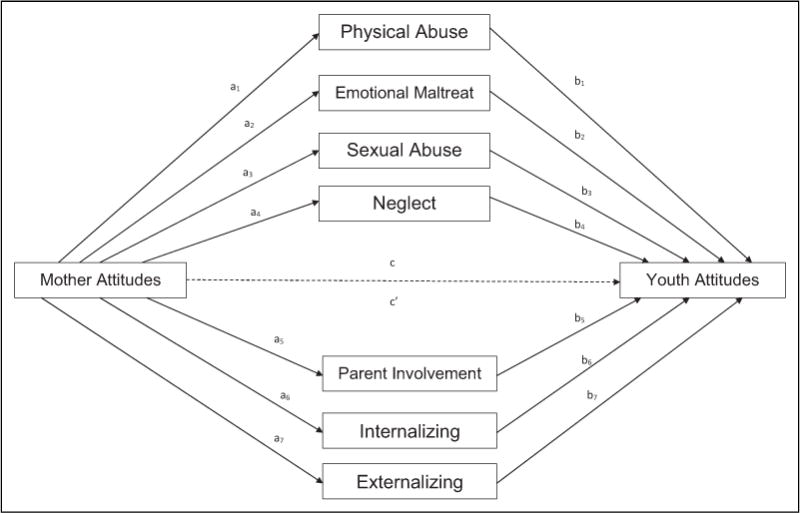

The model guiding this research is presented in Figure 1. In overview, particular aspects of the youths’ experience of parental behavior (child maltreatment and parental involvement) and youth psychosocial adjustment can be seen as both resulting from mothers’ parenting attitudes and in turn predicting youth parenting attitudes. Each of these classes of potential intervening variables is briefly discussed.

Figure 1.

A general multiple mediation model of the relationship between mother and youth attitudes.

The Role of Experiences of Maltreatment in Parenting Attitudes

There are a host of reasons to expect that maltreatment, both acts of commission (sexual, physical, or emotional abuse) and omission (neglect), would affect the development of parenting attitudes. First, such experiences have wideranging implications for youth functioning in general, with psychosocial effects often lasting into adulthood (see Felitti & Anda, 2010; Runyan, Wattam, Ikeda, Hassan, & Ramiro, 2002). Among a myriad of other psychosocial costs of maltreatment, individuals with a history of child maltreatment are at elevated risk of perpetuating the cycle of abuse by engaging in maltreatment of their own children (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011; Dixon, Browne, & Hamilton-Giachritsis, 2005). A variety of explanations exist for the family transmission of maltreatment risk (Berlin et al., 2011); however, a common theme across this work suggests that maltreatment may be part of a broader transmission of more global dimensions of parenting attitudes within families (Dixon et al., 2005).

Consistent with this notion, prior work suggests that particular parenting attitudes may not only be risk factors for engaging in child maltreatment but also be a possible precursor of maltreatment in the subsequent generation. For example, a history of child maltreatment has been linked to higher levels of hostility and lower levels of empathy toward one’s children as well as more willingness to use physical punishment as a disciplinary strategy (Bailey, DeOliveira, Wolfe, Evans, & Hartwick, 2012). In contrast, other work suggests that such outcomes of child maltreatment (and other traumas) are not inevitable (Grella & Greenwell, 2006; Lutenbacher & Hall, 1998). For example, some research has found that individuals with past maltreatment are no more likely to use physical punishment than those without the experience of maltreatment (Meyers & Battisoni, 2003). This apparent contradiction in the literature remains unresolved but suggests the critical importance of identifying the mechanisms by which parenting attitudes are transmitted in families of children vulnerable to maltreatment as well as the intervening role of maltreatment itself (Locke & Newcomb, 2004). Yet, research to date on intervening variables has been limited largely to retrospective reports of childhood experiences by adults with past maltreatment (e.g., Berlin et al., 2011; Dixon et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2010), precluding the opportunity to better understand the development of parenting attitudes over time.

Parent Involvement and Parenting Attitudes

In addition to maltreatment experiences in particular, there is some evidence that more general dimensions of parenting behavior may partially explain the link between mother and youth parenting attitudes. During adolescence in particular, warmth and involvement in the parent–youth relationship is likely to reinforce positive views of parenting. Conversely, distant or hostile relationships are likely to reinforce negative views of parenting. Although this link requires further study, there is some suggestion that parents’ empathy and appropriate views on roles predict parental involvement (Paulhus, 1994). Rather than a unidirectional process, parental involvement is best viewed as a reciprocal process between parents and children, a process that is integral to the development and maintenance of a positive parent–child relationship (Dishion & McMahon, 1998; also see Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Thus, negative parenting attitudes may lead to less engagement and involvement in the child’s life. In turn, this emotional distance in the parent–child relationship may have cascading effects for more negative parenting attitudes for youth later in life as well.

Youth Psychosocial Adjustment and Parenting Attitudes

Finally, child psychosocial adjustment may intervene in the association between caregiver and youth parenting attitudes as well. In particular, parenting attitudes are likely to influence youth adjustment via parenting behavior (e.g., Shaw et al., 2003). Less is understood about how youth adjustment in the context of specific parenting attitudes shapes their own parenting attitudes later in life. Mothers with less optimal maternal attitudes about parenting early in a child’s life may be experienced by the child as cold, harsh, or indifferent, hindering the development of a healthy parent–child relationship and subsequently exacerbating youth adjustment problems, including both internalizing and externalizing problems. In turn, a robust literature documents the association between psychosocial adjustment problems and compromised attitudes about parenting and unrealistic expectations for child behavior in both teen and adult caregivers (see Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000; Smith, 2004, for reviews).

There is a large body of research on the influence of mental illness, especially depression, on parenting attitudes (e.g., Lutenbacher & Hall, 1998). Depressive symptoms have been found to predict lower levels of empathy in mothers (Lutenbacher & Hall, 1998) and have been linked to a host of negative parent behaviors (Lovejoy et al., 2000). Less is known about the effects of externalizing problems on parenting attitudes.

Hypotheses

In the current study, we prospectively explored the direct effects of maternal parenting attitudes on later youth parenting attitudes as well as the indirect or intervening roles of family and individual process variables (maltreatment, parental involvement, and youth adjustment). Given the central relevance of considering the role of developmental context in studies of child and family functioning (Cummings et al., 2000), we examined maternal parenting attitudes during the early childhood of their children (age 4). The toddler years are considered a key developmental phase for the study of parenting attitudes, given increases in child language, mobility, and independence, which have the potential to dramatically impact a child’s experience and interpretation of parenting attitudes and subsequently impact both parenting behavior and youth adjustment (Waller et al., 2012). We then examined the emergence of early adult parenting attitudes among youth at age 18, an age at which emerging adults are often transitioning to or at least considering the formation of families and transition into parental roles. Of note, this developmental period can be a particularly critical developmental window when considering the role of early adverse experiences, particularly for youth with past maltreatment who are more likely than those without past maltreatment to transition to parental roles by age 18 (Hillis et al., 2004; Thompson & Neilson, 2014; Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2006). Accordingly, we anticipated that there would be consistency between early maternal parenting attitudes and youth parenting attitudes approximately 14 years later and that these associations would be at least partially accounted for by intervening maltreatment, parental involvement, and/or youth adjustment.

Thus, we tested the following hypotheses in a longitudinal sample of children identified as maltreated or at risk of maltreatment and followed through emerging adulthood:

Maternal parenting attitudes in four domains (appropriate expectations, empathy, rejection of punishment, and appropriate roles) assessed at child age 4 predict youth parenting attitudes at age 18.

These direct effects would be explained by intervening indirect links through the following domains: child maltreatment (physical abuse, emotional maltreatment, sexual abuse, and/or neglect), parental involvement, and youth psychosocial functioning (internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems).

Methods

Sample and Design

The current analyses used data collected from Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN), a consortium of five studies using shared instruments and interview protocols. Each site recruited child–caregiver dyads into the study at age 4 or 6 based on a variety of selection criteria including risk of or exposure to child maltreatment. Detailed information on design and recruitment of the larger LONGSCAN study is available from Runyan et al. (1998); however, several details relevant to these specific analyses will be presented here.

Baseline data were collected in a staggered manner across the sites, beginning in 1990 and ending in 1998. The five sites differed in terms of recruitment criteria: Two sites included children who had been reported for maltreatment (one of these sites recruited children deemed at “moderate” risk in terms of safety, while the other recruited children who had been removed from their primary caregiver because of child protection concerns), two sites included children at risk for maltreatment (one defined children as being at risk due to demographic factors such as family poverty or low birth weight, and one as defined by attendance at pediatric clinics serving children with nonorganic failure to thrive, and children of drug-abusing or HIV-positive mothers), and one site included both children who had been officially reported as maltreated and children who were identified as at risk, based on mother’s age and community and family poverty.

The baseline sample of LONGSCAN consisted of 1,354 caregiver–child dyads. The institutional review boards at each of the five sites reviewed and approved the LONGSCAN study procedures. For all interviews, except age 18, caregiver respondents provided consent for their own participation and the participation of their children, with children providing assent beginning at age 8. For the age 18 interviews, youth respondents provided consent for their own participation.

Face-to-face interviews were conducted with children aged 4, 6, 8, 12, 14, 16, and 18 (the end of the LONGSCAN data collection). At each interview, children/adolescents and caregivers were interviewed separately. Variables assessed were informed by developmental–ecological theory, with attention to developmentally appropriate measurement of constructs over time. Because of the developmental changes over the course of the study, by design, each interview included a somewhat different complement of measures. As well, there was periodic ongoing review of Child Protective Services (CPS) records in local jurisdictions or states, where participating sites were located to identify new reports of child maltreatment.

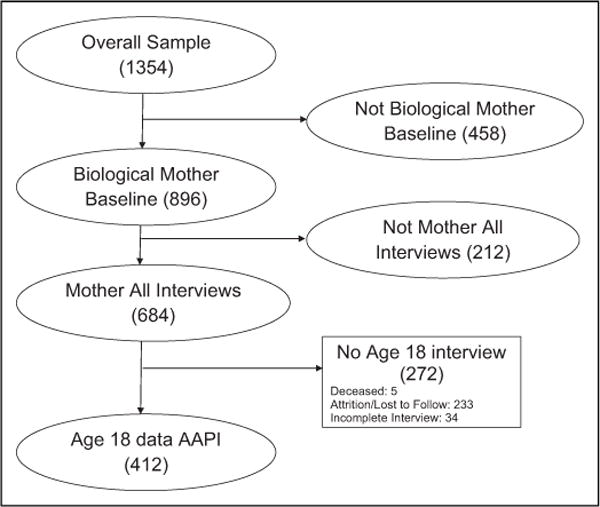

The key question in the study was whether there is a relationship between mother’s attitudes toward parenting and adolescent’s attitudes toward parenting. To examine this question, we restricted the sample to those dyads characterized as follows: (1) the baseline caregiver respondent was the biological mother and (2) the same caregiver respondent participated in all LONGSCAN interviews. This was necessary to allow a clear examination of the influence of mother parenting attitudes on youth parenting attitudes. As shown in Figure 2, the application of these inclusion criteria, along with loss to follow-up (in particular the lack of data at age 18), resulted in an analysis sample of 412.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of arrival at sample.

As is common in longitudinal research, data were occasionally missing on some of the intermediate variables (parent involvement, youth emotional/behavioral functioning) at some assessment periods. For these variables, mean scoring of the different assessment time points was used to produce an overall mean score on the particular variable as a means of dealing with missing data. The information on the analysis sample is presented in Table 1. More than half of the youth sample (60%) was African American, with a slight preponderance of female youth (53.9%).

Table 1.

Description of Sample.

| M (SD) | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables (age 18) | ||

| Youth Race | ||

| African American | 247 (60.0) | |

| White | 107 (26.0) | |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 58 (14.0) | |

| Mother Marital Status | ||

| Single | 201 (48.8) | |

| Formerly | 89 (21.6) | |

| Married | 122 (29.6) | |

| Family Income: | ||

| Under US$15,000 | 233 (56.5) | |

| US$15,000 or over | 179 (43.5) | |

| Has become a parent | ||

| Yes | 59 (14.3) | |

| No | 353 (85.7) | |

| Youth gender | ||

| Female | 222 (53.9) | |

| Male | 190 (46.1) | |

| Site: | ||

| Eastern | 115 (27.9) | |

| Southern | 115 (27.9) | |

| Midwestern | 59 (14.3) | |

| Northwestern | 86 (20.9) | |

| Southwestern | 39 (9.0) | |

| Youth Parenting Attitudes | ||

| Expectations | 23.38 (4.05) | |

| Empathy | 26.04 (5.81) | |

| Rejection of Punishment | 33.45 (7.74) | |

| Roles | 22.23 (6.75) | |

| Mother Parenting Attitudes | ||

| Expectations | 23.88 (3.61) | |

| Empathy | 29.37 (5.46) | |

| Rejection of Punishment | 35.82 (6.31) | |

| Roles | 28.52 (6.71) | |

| Potential Intervening Variables | ||

| Physical Abuse | 170 (41.3) | |

| Official | 86 (20.9) | |

| Self-Report | 105 (25.5) | |

| Emotional Maltreatment | 183 (44.4) | |

| Official | 83 (20.1) | |

| Self-Report | 132 (32.0) | |

| Sexual Abuse | 63 (15.3) | |

| Official | 46 (11.4) | |

| Self-Report | 23 (5.6) | |

| Neglect (Official) | 128 (31.1) | |

| Parental Involvement | 1.64 (0.30) | |

| CBCL Internalizing | 6.35 (4.63) | |

| CBCL Externalizing | 11.26 (6.84) |

Note. N = 412. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist.

Measures

Demographic and control variables

Control variables included study site, gender, and race/ethnicity of the target youth. For the purposes of the current study, race/ethnicity was coded as White, African American, and other. Other demographic variables were also included in the descriptive analysis of the sample, specifically, family income, mother marital status, and youth parenting status. These variables are reported as assessed during the age 18 interview.

Mother and Youth Parenting Attitudes

Parenting attitudes were assessed with the Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory (AAPI; Bavolek, 1984). The AAPI is a 32-item measure that assesses attitudes toward parenting on four subscales: appropriate developmental expectations for children which acknowledge normative child development, empathy toward children and their needs and an interest in the child’s perspective, rejection of physical punishment as a means of discipline and conflict resolution with children, and appropriate family roles and the avoidance of role reversal or parentification. Participants indicate, on a 5-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree = 1; strongly disagree = 5) the extent to which they agree with statements about child behavior and parenting. The APPI was administered to mothers with children aged 4 and to youth aged 18.

The AAPI and the AAPI-2 have been validated on both adolescent and adult caregivers and correlate in expected ways with other measures of parenting attitudes and functioning. The measure was originally designed and validated to distinguish the parenting attitudes of maltreating and nonmaltreating parents (Bavolek, 1980, 1984; Bavolek & Keene, 2010). Coefficient αs, in the current sample, ranged from .73 (for expectations) to .87 (for roles) for youth and .75 (for expectations) to .88 (for roles) for mothers. In these analyses, the AAPI scales were treated as continuous variables, with higher scores indicating more positive or normative attitudes.

Child and family process variables

Because the youth parenting attitudes were assessed at age 18 and because most of the potential intervening variables included assessments about events or experiences leading up to the moment of assessment, there was concern that including age 18 measurements of these potential intervening variables would create the possibility of temporal overlap with youth parenting attitudes. Thus, these variables were examined up to the age 16 assessment and did not include the age 18 assessment. Each had been assessed multiple times and was summarized using either a mean (as in the case of parent involvement) or a dichotomization of periodically collected data (as in the case of maltreatment).

Maltreatment

Exposure to various forms of maltreatment was assessed using administrative records of CPS as well as youth self-report. Allegations of maltreatment to CPS were coded using the Modified Maltreatment Classification System (MMCS: English & LONGSCAN Investigators, 1997, a LONGSCAN-modified version of Barnett, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1993). The MMCS data collection included information on the form of the alleged maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological maltreatment, and neglect). This information was coded biannually by research staff who had at least 10 hr of training in coding and were trained to consensus. Interrater reliability for the coding of referrals was high, with κs ranging from .73 for emotional maltreatment to .87 for physical abuse. These analyses focused on reports of maltreatment that occurred between birth and age 16, coded as each of the four categories noted earlier.

In addition to this administrative data collection, the participants were asked, as part of the age 18 interview, to report whether they have had a variety of experiences that could be construed as physical or sexual abuse or emotional maltreatment. This self-report measure is described in more detail elsewhere, including the finding that there is a moderate correlation between self-reports of maltreatment and the administrative record reviews (Everson et al., 2008). The instrument was designed so that dichotomous stem questions focusing on the timing of the event (“Up to now, has a parent or other adult who was supposed to be supervising you or taking care of you ever done something to you like…”) with yes/no questions that described specific abuse experiences (e.g., “bruised you, or given you a black eye?” “put some part of their body or anything else inside your private parts or bottom?”). As recommended in previous studies (Everson et al., 2008), information from both self-report and administrative records was integrated to identify exposure to each type of maltreatment (i.e., if either self-report or administrative data indicated maltreatment, the youth was coded as having a history of maltreatment). Children frequently experience multiple forms of maltreatment; each form of maltreatment was dichotomized separately such that a given youth might be positive for any or all of the four forms of maltreatment coded.

Parental involvement

To assess experience of parental monitoring and involvement, adolescents at ages 12, 14, and 16 were given a 5-item self-report measure adapted by the LONGSCAN investigators (Knight, Smith, Martin, Lewis, & the LONGSCAN Investigators, 2008) from items used by Patterson and Stouthamer-Loeber (1984). Items assessed adolescents’ perception of caregiver concern for and knowledge of their friends, activities, whereabouts, and money use. One example item was “How much do your parent(s) really know about where you are most afternoons after school?” Response items ranged from 0 (they don’t know) to 2 (they know a lot). Cronbach’s α for this measure was .69 at age 12, .69 at age 14, and .79 at age 16. At each age, responses were averaged. To calculate an overall measure of parental involvement during adolescence, the parental involvement scores at ages 12, 14, and 16 were averaged, with higher scores indicating more parental involvement.

Youth emotional/behavioral functioning

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) was administered to assess caregiver ratings of adolescent emotional/behavioral functioning in two broad domains: internalizing problems and externalizing problems. Internalizing problems included items assessing anxiety/depression, somatic complaints, and social withdrawal. Externalizing problems included items assessing aggression and delinquency. The CBCL is a widely used and validated caregiver report of adolescent behavior problems (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The current analyses included a mean of the internalizing and externalizing raw scores based on reports from mothers at youth ages 12, 14, and 16 to provide an estimate of emotional/behavioral functioning during adolescence. Cronbach’s αs for internalizing and externalizing in this sample were above .89 for each broad-band scale administered at each age.

Analyses

As noted earlier, the purpose of this article was to examine the link between mother and youth attitudes about parenting and to examine potentially intervening variables in this link. For each of the four parenting attitudes, the link between mother and youth parenting attitude was examined with a block of potential intervening variables (physical abuse, emotional maltreatment, sexual abuse, neglect, parental involvement, youth internalizing problems, and youth externalizing problems) were examined. Study site, gender, and race were included as a block of control variables. Multiple mediation models allow for the examination of simultaneous mediation by more than one variable providing estimates of indirect/mediated effects in a fully multivariate context (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). In this study, the overall indirect effect of all potential mediators as well as specific indirect effects of each potential mediator was examined.

To estimate the indirect effects, a bootstrapping estimation procedure was used, as recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008). Bootstrap estimation uses the initial sample to generate multiple random samples that are the basis for parameter estimates. As recommended (Hayes, 2009; Preacher & Hayes, 2008), 5,000 samples were used to provide parameter estimates and confidence intervals. If these 95% confidence intervals did not include zero, this indicated that the indirect effect of the intervening variable was significant at p < .05 (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

The general model for these analyses is presented in Figure 1. Not represented in this figure are the covariates (site, race, and gender); all links described here represent relationships obtained after taking into account these variables. Coefficient a represents the link between mother attitudes and each potential mediator; coefficient b represents the link between each potential mediator and youth attitude. Coefficient c represents the total effect of mother attitudes on youth attitudes; coefficient c′ represents the remaining direct effect of mother attitudes on youth attitudes after partialling out indirect effects. It is important to note that coefficient c is the equivalent of a direct effect between mother and youth attitudes in a multi-variate context, representing a test of Hypothesis 1. The indirect effect is the product of coefficients a and b for each specific indirect effect in this context, while the general indirect effect is the sum of these products. It is important to note that because the specific indirect effects could be either positive or negative (and in most cases, both positive and negative indirect effects were obtained), and the general indirect effect is the sum of these specific effects, it was very possible to have significant specific indirect effects, while the general indirect effect was nonsignificant. The tests of these indirect effects represent tests of Hypothesis 2.

It is important to briefly review the logic underlying this approach to testing indirect effects, as it is somewhat counterintuitive. In traditional mediation analysis, mediation was inferred to have occurred if a significant main effect relationship was no longer significant after taking into account potential mediators. However, as noted by Hayes (2009), indirect effects represent the differences between the main effect without taking into account potential intervening variables and the main effect after taking into account these intervening variables (in other words, a significant reduction of c to c′). Such a reduction may be significant, regardless of the significance of either c or c′.

Finally, because a small percentage of the sample were already parents at 18 years of age and having become a parent may have an impact on attitudes toward parenting, the statistical analyses were run with and without those who had become parents in the sample. Because the results did not differ with those who had become parents left out, the results for the full sample are being reported.

Results

The correlations among the variables examined are presented in Table 2. Of note, for each of the four parenting attitude variables, the zero-order correlations between mother and youth attitudes were significant, specifically appropriate expectations (r = .15), empathy (r = .29), rejection of punishment (r = .17), and roles (r = .24).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Main Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Mother Expectations | — | .58* | .58* | .58* | .02 | .10* | .02 | −.05 | .09 | −.12* | −.09 | .15* | .16* | .11* | .20* |

| 2.Mother Empathy | — | — | .55* | .72* | .06 | .18* | .02 | .00 | .09 | −.11* | −.07 | .19* | .29* | .13* | .28* |

| 3.Mother Rejection Pun | — | — | — | .52* | .02 | .12* | .03 | .04 | .04 | −.10* | −.11* | .18* | .17* | .17* | .20* |

| 4.Mother Roles | — | — | — | — | .02 | .12* | .05 | −.02 | .11* | −.07 | −.03 | .14* | .24* | .09 | .24* |

| 5.Physical Abuse | — | — | — | — | — | .41* | .23* | .32* | −.15* | .12* | .25* | .02 | −.01 | .04 | .08 |

| 6.Emotional Maltreatment | — | — | — | — | — | — | .19* | .36* | −.12* | .12* | .17* | .09 | .09 | .07 | .13* |

| 7.Sexual Abuse | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .28* | −.09 | .11* | .16* | .09 | .04 | .12* | .14* |

| 8.Neglect | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | −.16* | .14* | .26* | −.05 | −.01 | .11* | .05 |

| 9.Parental Involvement | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | −.18* | −.29* | .06 | .15* | .10 | .00 |

| 10.CBCL Internalizing | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .67* | −.07 | .00 | −.09 | .00 |

| 11.CBCL Externalizing | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | −.04 | −.07 | −.05 | −.02 |

| 12.Youth Expectations | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .54* | .54* | .52* |

| 13.Youth Empathy | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .58* | .58* |

| 14.Youth Rejection Pun | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .51* |

| 15.Youth Roles | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Note. N = 412.

p < .05.

For each of the four parenting attitudes, tests of direct effects are seen in the corresponding figure, while Table 3 lists each indirect effect, along with its significance test. These results are described as organized by parenting attitude.

Table 3.

Indirect Effects of Proposed Intervening Variables Linking Early Mother Attitudes to Later Youth Attitudes.

| Intervening Variable | Appropriate Expectations | Empathy | Rejection of Punishment | Roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Specific Effects | Point estimate (CI) | Point estimate (CI) | Point estimate (CI) | Point estimate (CI) |

| Physical Abuse | −.0001 [−.0109, .0082] | −.0008 [−.0162, .0037] | .0064 [−.0020, .0330] | −.0019 [−.0174, .0025] |

| Emotional Maltreatment | .0009 [−.0036, .0156] | −.0007 [−.0134, .0060] | .0000 [−.0072, .0081] | .0008 [−.0029, .0136] |

| Sexual Abuse | −.0013 [−.0173, .0045] | .0013 [−.0037, .0169] | −.0017 [−.0186, .0038] | −.0001 [−.0068, .0045] |

| Neglect | .0259 [.0047, .0657]* | .0064 [−.0131, .0334] | −.0109 [−.0398, .0090] | .0056 [−.0141, .0272] |

| Parental Involvement | .0018 [−.0097, .0208] | .0110 [.0003, .0327]* | .0053 [−.0018, .0278] | −.0047 [−.0228, .0043] |

| CBCL Internalizing | .0174 [−.0054, .0597] | −.0182 [−.0539, .0026] | .0373 [.0071, .0864]* | .0038 [−.0135, .0277] |

| CBCL Externalizing | −.0029 [−.0325, .0227] | .0199 [.0013, .0534]* | −.0187 [−.0656, .0168] | .0037 [−.0054, .0255] |

| General Effects | .0421 [.0064, .0901]* | .0189 [−.0161, .0617] | .0177 [−.0209, .0656] | .0071 [−.0223, .0402] |

Note. CI = 95% confidence interval. Analyses included the following control variables: site, race, and gender. Estimates of indirect effects derived from Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) multiple mediator models. Bias corrected using 5000 resamples.

p < .05.

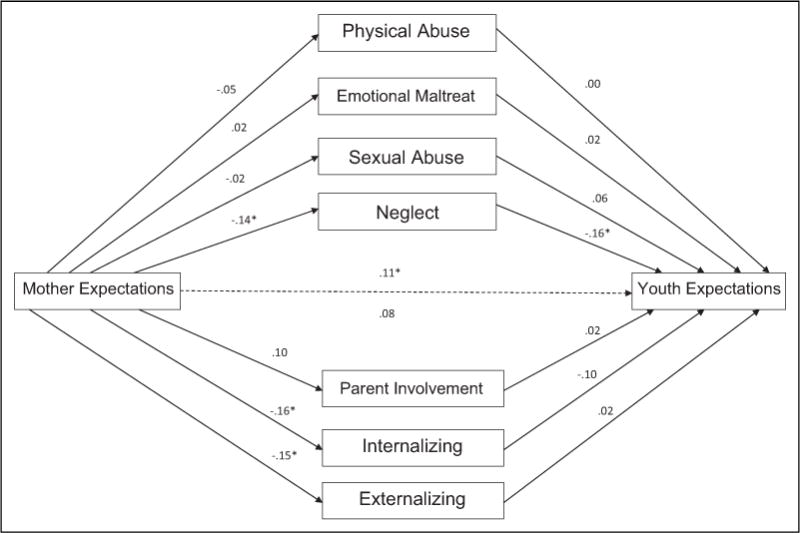

Appropriate Expectations

The indirect effects multiple mediation model for appropriate expectations is presented in Figure 3, and the estimates of general and specific indirect effects (after accounting for covariates) are presented in the first column of Table 3. As indicated, after allowance for the potential influence of the covariates, the total effect of maternal appropriate expectations on youth expectations was significant. It was no longer significant after taking into account the block of potential mediators. The general indirect effect of the potential mediators was significant as was the specific indirect effect of neglect. Consistent with this, the links from mother appropriate expectations to neglect (B = −.14) and from neglect to youth appropriate expectations (B = −.16) were significant. Maternal appropriate expectations was also significantly related to youth internalizing (B = −.16) and youth externalizing (B = −.15).

Figure 3.

A multiple mediation model of the relationship between mother and youth appropriate expectations. The statistical model and path coefficients represent effects after controlling for site, child gender, and race/ethnicity. Numerical values represent standardized path coefficients.

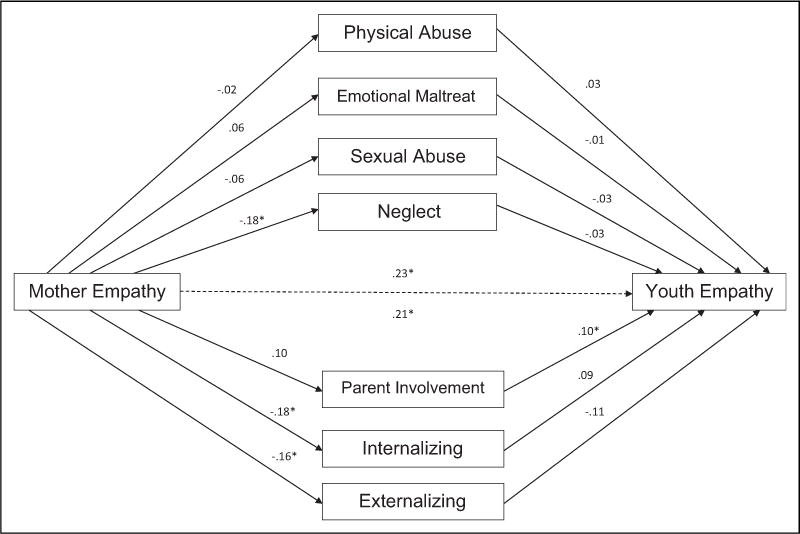

Empathy

The indirect effects multiple mediation model for empathy is presented in Figure 4, and the estimates of indirect effects (after accounting for covariates) are presented in the second column of Table 3. After allowance for the potential influence of the covariates, the total effect of mother empathy on youth empathy was significant, and this remained the case after taking into account the potential mediators. The general indirect effect was not significant, although the specific indirect effects of parental involvement and youth externalizing were significant. There was a significant link between mother empathy and youth externalizing (B = −.16), although the link from youth externalizing to youth empathy was not significant (B = −.11). There was a significant link between parent involvement and youth empathy (B = .10), although the link from mother empathy to parent involvement was not significant (B = .10). Although these were the only significant specific indirect effects, there were also significant links from mother empathy to neglect (B = −.18) and internalizing (B = −.18).

Figure 4.

A multiple mediation model of the relationship between mother and youth empathy. The statistical model and path coefficients represent effects after controlling for site, child gender, and race/ethnicity. Numerical values represent standardized path coefficients.

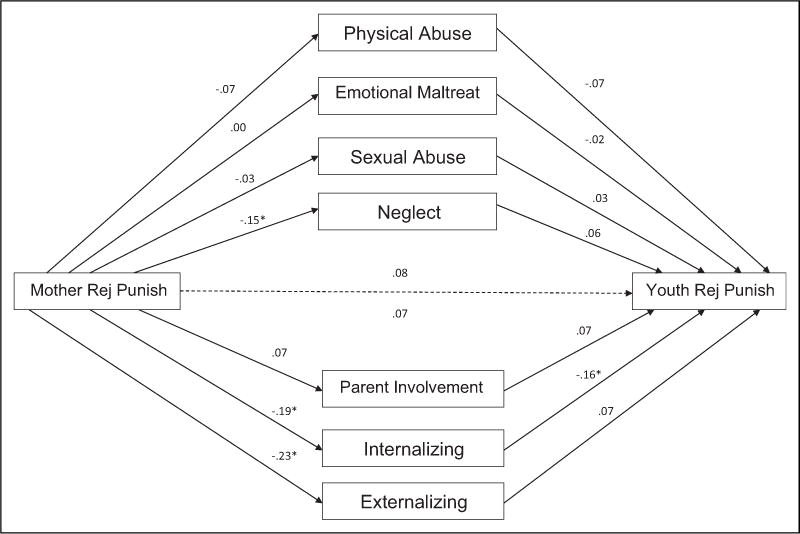

Rejection of Punishment

The indirect effects multiple mediation model for rejection of physical punishment is presented in Figure 5, and the estimates of indirect effects (after accounting for covariates) are presented in the third column of Table 3. After allowance for the potential influence of the covariates, the total effect of mother rejection of punishment on youth rejection of punishment was not significant. The general indirect effect was not significant, although the specific indirect effect of youth internalizing was significant. Consistent with this effect, there was a significant link from mother rejection of punishment to youth internalizing (B = −.19) and from youth internalizing to youth rejection of punishment (B = −.16). Although this was the only significant specific indirect effect, there were also significant links from mother rejection of punishment to neglect (B = −.15) and youth externalizing (B = −.23).

Figure 5.

A multiple mediation model of the relationship between mother and youth rejection of punishment. The statistical model and path coefficients represent effects after controlling for site, child gender, and race/ethnicity. Numerical values represent standardized path coefficients.

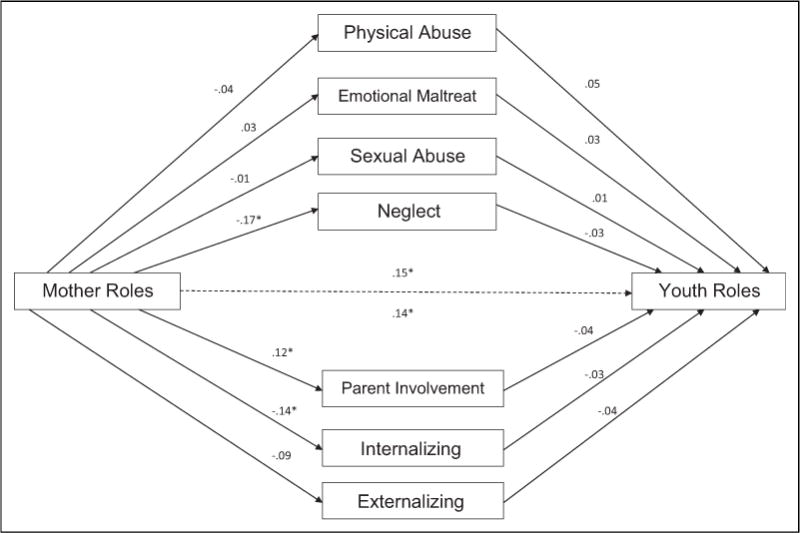

Roles

The indirect effects multiple mediation model for roles is presented in Figure 6, and the estimates of indirect effects (after accounting for covariates) are presented in the fourth column of Table 3. After allowance for the potential influence of the covariates, the total effect of mother roles on youth roles was significant, and this remained true after taking into account the potential mediators. The general indirect effect was not significant nor were the specific indirect effects of any of the potential mediators examined. There were significant links from mother roles to neglect (B = −.17), parent involvement (B = .12), and youth internalizing (B = −.14).

Figure 6.

A multiple mediation model of the relationship between mother and youth roles. The statistical model and path coefficients represent effects after controlling for site, child gender, and race/ethnicity. Numerical values represent standardized path coefficients.

Discussion

The current study examined the associations between mother and youth attitudes toward parenting in a subsample from LONGSCAN (a prospective, multisite study of children and youth at high risk for maltreatment). Direct associations as well as the intervening roles of several family and youth process variables were examined. Findings highlighted the family transmission of early parenting attitudes from mothers to their children in emerging adulthood, although the nature of the associations varied by the dimension of parenting attitude. Specifically, there were direct effects for maternal appropriate expectations, empathy, and roles at child age 4 on consonant youth attitudes at age 18 but not for rejection of punishment, after taking into account gender, race, and site. Although these direct effects were significant, they were relatively modest, suggesting the importance of examining potential mediators and moderators. In examining the evidence for indirect effects, the findings also highlight potential mechanisms accounting for the transmission of parenting attitudes. The pattern of these indirect effects, however, varied by parenting attitude and the intervening variable examined.

The significant relationships between parenting attitudes of mothers and those of emerging adults add support to a growing body of evidence for the transmission of parenting attitudes across generations (Berlin et al., 2011; Dixon et al., 2005). The current study suggests that this continuity is also present in parenting attitudes as measured by the AAPI (Bavolek, 1984). The strongest intergenerational link was for empathy, a key determinant of parenting behavior and child outcomes (De Paul & Guilbert, 2008; Wiehe, 2001). As well, it is noteworthy that both parental involvement and youth externalizing problems had indirect effects on this link. Research on early development has suggested that positive and empathic parental involvement leads to the development of empathy in children (e.g., Zhou et al., 2002). However, a dearth of information remains about longer term relationships between these variables, including how children who subsequently enter emerging adulthood view children. In addition, although externalizing problems have been linked to general deficits in empathy (Miller & Eisenberg, 1988), it is also possible that such problems are important in the development of empathy toward one’s children.

There was also a significant link between mothers’ and emerging adult children’s appropriate expectations, and these links were partially explained by neglect. Parents who have unrealistic beliefs about children’s developmental capacities may be especially at risk of engaging in neglect of their children (Azar, Robinson, Hekimian, & Twentyman, 1984). Indeed, education about children’s developmental capacities is a key component of many prevention efforts around child neglect (Corcoran, 2000). Our finding suggests, in turn, that experiences of neglect in childhood may be linked to emerging adults’ later problems in understanding children’s developmental needs. Whether inappropriate expectations of parents are modeled and internalized, or that children who have been neglected attribute such experiences as normative rather than problematic (Azar et al., 1984), it appears that this form of maltreatment puts youth at particular risk for misunderstanding the developmental needs of their own children.

There were also significant links between roles for mother and emerging adult youth, although none of the potential intervening variables explained this link. Lower scores in the domain of roles can be construed as similar to the concept of “parentification” or “role reversal” (Hooper, 2007). Given this overlap in constructs, it is somewhat surprising that neglect and other forms of maltreatment failed to influence this link. Although beyond the scope of the current study, it may be that the problematic parental behaviors associated with role reversal are unlikely to be detected by CPS authorities or fail to meet the thresholds typically applied.

It is striking that there was no significant main effect between mother and youth attitudes toward physical punishment (Hypothesis 1); however, the finding that these two variables were associated via the indirect effect of internalizing problems (Hypothesis 2) is consistent with advances in theory and statistical modeling (see Hayes, 2009, for a review). As summarized by Hayes (2009, pp. 413–414):

it is possible for M [mediator] to be causally between X and Y even if X and Y aren’t associated … That X can exert an indirect effect on Y through M in the absence of an association between X and Y becomes explicable once you consider that a total effect is the sum of many different paths of influence, direct and indirect, not all of which may be a part of the formal model.

It is also apparent that the presence of the covariates is at least partially responsible for this lack of a significant main effect as evidenced by the significant zero-order effects of mothers’ attitudes toward physical punishment and on youth attitudes toward physical punishment presented in Table 2. It is possible that the covariates attenuated this main effect more than they attenuated the specific indirect effect. The specific indirect effect is to be expected, as there is a large body of research linking both the experience of physical punishment to child negative affectivity (Runyan et al., 2002) and parent negative affectivity to the use of physical punishment (Berlin et al., 2011).

Substantively, there are several possible explanations for this lack of a main effect. Secular attitudes toward corporal punishment have changed during the course of the data collection (Zolotor, Theodore, Runyan, Chang, & Laskey, 2011). As well, this discrepancy is consistent with prior research noting intergenerational discontinuities in attitudes toward physical punishment (Grella & Greenwell, 2006; Lutenbacher & Hall, 1998; Meyers & Battisoni, 2003). One possible additional explanation for this discrepancy may relate to whether those who were physically punished regard such punishment as abusive. Those who experienced punishment as children vary greatly in terms of their attributions about it, and further research is needed to understand the source of such attributions (Bower & Knutson, 1996). Such attributions may suggest a potent area for prevention. Indeed, one possibility raised by this research is that, in planning services for families referred to CPS, it may be useful to include an evaluation of parents not only for their own experiences of being parented but for parenting attitudes as well. It is noteworthy that the significant indirect effect was through youth internalizing problems, suggesting a mental health component to the explanation, which, as noted earlier, is consistent with what is known about negative affectivity and punitive parenting. Finally, it is likely that broader contextual factors, including generational effects, may account for some discrepancy (Ben-Arieh & Haj-Yahia, 2008; Scott, 2000). Of course, broader contextual factors may also underlie some of the similarities between parents and youth.

As with all research, these analyses are not without limitations. First, this was a relatively high-risk sample of youth in emerging adulthood. Although we view this as a strength of the study, findings may not generalize to community-based populations. In addition, the sample included primarily emerging adults who had not yet become parents (85.7% of the sample). This characteristic of the sample should be kept in mind, as prior work suggests that parents tend to report more positive attitudes than do nonparents (Bavolek, 1984; Solis-Camera & Romero, 1996). Although there are reasons to expect continuity in parenting attitudes before and after becoming a parent, this needs to be empirically tested. On the other hand, the low severity of most reported forms of physical and sexual abuse in this study (Everson et al., 2008) may explain the limited effects of these variables. Third, only maternal attitudes were assessed in the current study. Although it is true that mothers remain the primary caretakers, the exclusion of fathers is an oft-cited limitation of family-focused research more generally (see Lamb, 2010; Phares, Lopez, Fields, Kamboukos, & Duhig, 2005). In turn, future research should make more substantive efforts to include fathers and to examine the role of fathers’ parenting attitudes and their direct and intervening influences on their emerging adult children (Lunkenheimer et al., 2006).

Fourth, this study focused on several intervening processes in particular, as we were most interested in understanding those that may account for family transmission of parenting attitudes. That said, we focused on a relatively narrow subset of intervening variables and, in particular, those that had a foundation of research demonstrating that they are amenable to preventive interventions. Future work in this area should explore other potential intervening variables such as interpersonal dependency, mother alcohol and/or drug use, youth educational achievement, and very early parenting by youth. Fifth, it is likely that some youth personality variables (Bornstein, 2005), parenting status of youth, and youth social support might act as moderators. In our own analyses, there were some effects of gender and race/ethnicity that merit further exploration. In particular, the effects of gender were quite strong. Little work has examined the parenting attitudes of young men, and this is an area that merits further study (Woodward et al., 2006).

On a related front, these variables were summarized over a relatively long period of time (adolescence for parent involvement and psychosocial adjustment; lifetime for child maltreatment). This approach to assessment is likely to have limited the developmental sensitivity of these effects. To the extent to which the intervening variables had effects, they may have had most of their influence in more narrow windows of time. Thus, averaging across adolescence may have diluted these effects of intervening variables or obscured changes in influence over time. Because the indirect effects model included several covariates, which appear to have attenuated the links between mother and youth attitudes, this should be seen as a relatively conservative estimate of these links. There was some variation in this apparent attenuation with rejection of punishment appearing to be attenuated the most. Further, given the time period between maternal and youth assessment, additional intervening variables may have contributed to the findings reported. Future research should examine in more detail the effects of timing of such variables, especially in relation to parenting status.

Because the intergenerational transmission of parenting attitudes was not a primary focus of these data at the time they were collected, the timing of the assessments of both mother and youth parenting attitudes did not vary. Although in both cases, the timing seemed convenient, repeated measures for each would have provided a great deal of insight into the processes underlying the links between them. Although not a limitation, it is important to emphasize that the outcomes studied here were parenting attitudes not parental behavior. Parental behavior is multidetermined, and parenting attitudes are only one component (Barnett et al., 2010).

Other strengths of the study should also be noted. First, this study examined the development of parenting attitudes among emerging adults at risk for perpetuating maltreatment with their own children as a function of their own early adverse experiences. It is critical to better understand these dynamics in high-risk groups if we are to tailor our preventive interventions to best fit their vulnerability and needs as they enter the age of potential parenthood themselves. In addition, although most studies of the development of parenting attitudes are retrospective and, in turn, vulnerable to bias, this study is prospective. As such, the findings shed light on the development of parenting attitudes in emerging adults as a function, in part, of their own mothers’ parenting attitudes and other childhood and family processes. Third, this study examined the potential transmission of parenting attitudes across particularly important stages of development. The toddler years, the age range at which maternal parenting attitudes were assessed, are considered a key developmental phase for understanding parenting attitudes, given the dramatic developmental changes occurring for children and the associated impact on the parent–child relationship. Then, we examined parenting attitudes among youth in emerging adulthood at age 18, a period that is particularly important in understanding the development of parenting attitudes in a group of youth who are on the threshold of becoming or may already have become parents themselves. Finally, this study identified several potential mechanisms (e.g., neglect) accounting for the transmission of attitudes, each of which is amenable to preventive interventions aimed at high-risk families.

In summary, the findings presented here highlight family transmission of key attitudes toward parenting, suggesting potentially important windows of opportunity for enhancing parenting attitudes across multiple generations. Our findings suggest that parenting interventions may not only have immediate implications for current maternal parenting behavior and youth adjustment but later youth parenting attitudes as well. Importantly, there exist a host of behavioral parent training programs, each of which has as its central focus the improvement of the parent–child relationship in early childhood via modification of both parenting attitudes and parenting behavior (see Forehand, Jones, & Parent, 2013). In fact, such programs have already proven efficacious in modifying parenting behavior among maltreating parents (see Barth, 2009); and it is likely that these effects are due in part to changes in parenting attitudes, including those assessed in this study (Mah & Johnson, 2008). Moreover, we are not yet aware of studies examining the extent to which such programs have lasting effects on later youth parenting attitudes when they reach the age of potential parenthood. This may be an important direction for future work if we are to better understand the extent to which family transmission of parenting attitudes is amenable to intervention.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse, Grant Number1R01DA031189.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for child behavior checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Azar ST. Adult development and parenthood. In: Demick J, editor. Adult Development. New York: Sage; 2003. pp. 391–416. [Google Scholar]

- Azar ST, Robinson DR, Hekimian E, Twentyman CT. Unrealistic expectations and problem-solving ability in maltreating and comparison mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:687–691. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey HN, DeOliveira CA, Wolfe VV, Evans EM, Hartwick C. The impact of childhood maltreatment history on parenting: A comparison of maltreatment types and assessment methods. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2012;36:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1993. pp. 7–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MA, Shanahan L, Deng S, Haskett ME, Cox MJ. Independent and interactive contributions of parenting behaviors and beliefs in the prediction of early childhood behavior problems. Parenting: Science & Practice. 2010;10:43–59. doi: 10.1080/15295190903014604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP. Preventing child abuse and neglect with parent training: Evidence and opportunities. Future of Children. 2009;19:95–118. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavolek SJ. Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) Au Claire, WI: Wisconsin University; 1980. Primary prevention of child abuse: Identification of high risk parents. [Google Scholar]

- Bavolek S. Handbook for the AAPI (Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory) Park City, UT: Family Development Resources; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bavolek SJ, Keene RG. AAPI online development handbook. 2010 Retrieved from http://nurturingparenting.com/images/cmsfiles/aapionlinehandbook12-5-12.pdf.

- Ben-Arieh A, Haj-Yahia MM. Corporal punishment of children: A multi-generational perspective. Journal of Family Violence. 2008;23:687–695. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, Dodge KA. Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development. 2011;82:162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein RF. Interpersonal dependency in child abuse perpetrators and victims: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2005;27:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bower ME, Knutson JF. Attitudes toward physical discipline as a function of disciplinary history and self-labeling as physically abused. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1996;20:689–699. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Johnston C. Parental and child cognitions in the context of the family. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:315–344. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JG, Shaver PR, Li CS, Minzenberg MJ. Childhood maltreatment, adult attachment, and depression as predictors of parental self-efficacy in at-risk mothers. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma. 2011;20:596–616. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran J. Family interventions with child physical abuse and neglect: A critical review. Children and Youth Services Review. 2000;22:563–591. [Google Scholar]

- Craig L, Mullan K. How mothers and fathers share child-care: A cross-national time-use comparison. American Sociological Review. 2011;76:834–861. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De Paul J, Guibert M. Empathy and child neglect: A theoretical model. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008;32:1063–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Browne K. Attributions and behaviours of parents abused as children: A mediational analysis of the intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment (Part II) Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:58–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, LONGSCAN Investigators Modified Maltreatment Classification System (MMCS) 1997 Retrieved from the LONGSCAN website http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/

- Everson MD, Smith J, Hussey JM, English D, Litrownik AJ, Dubowitz H, Runyan DK. Concordance between adolescent reports of childhood abuse and Child Protective Service determinations in an at-risk sample of young adolescents. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:14–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559507307837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF. The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult medical disease, psychiatric disorders and sexual behavior: Implications for healthcare. In: Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Pain C, editors. The impact of early life trauma on health and disease: The hidden epidemic. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2010. pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Jones DJ, Parent J. Behavioral parenting interventions for child disruptive behaviors and anxiety: What’s different and what’s the same. Clinical Psychology Review. 2013;33:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Greenwell L. Correlates of parental status and attitudes toward parenting among substance-abusing women offenders. Prison Journal. 2006;86:89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE. Parents’ attitudes and beliefs: Their impact on children’s development. In: Tremblay RE, Boivin M, Peters RDeV, editors. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online] 2. Montreal, Quebec: Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development and Strategic Knowledge Cluster on Early Child Development; 2008. Available at: http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/documents/GrusecANGxp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76:408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics. 2004;113:320–327. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Buck MJ. Parental attitudes toward child-rearing. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting; vol 3: Being and becoming a parent. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 537–562. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LM. Expanding the discussion regarding parentification and its varied outcomes: Implications for mental health research and practice. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2007;29:322–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Trickett PK, Putnam FW. Childhood experiences of sexual abuse and later parenting practices among non-offending mothers of sexually abused and comparison girls. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2010;34:610–622. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight ED, Smith JB, Martin LM, Lewis T, the LONGSCAN Investigators Measures for assessment of functioning and outcomes in longitudinal research on child abuse volume 3: Early adolescence (ages 12–14) 2008 Retrieved from LONGSCAN website, http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/

- Lamb ME. The role of the father in child development. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Locke TF, Newcomb MD. Child maltreatment, parent alcohol- and drug-related problems, polydrug problems, and parenting practices: A test of gender differences and four theoretical perspectives. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:120–134. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer ES, Kittler JE, Olson SL, Kleinberg F. The intergenerational transmission of physical punishment: Differing mechanisms in mothers’ and fathers’ endorsement? Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21:509–519. [Google Scholar]

- Lutenbacher M, Hall LA. The effects of maternal psychosocial factors on parenting attitudes of low-income, single mothers with young children. Nursing Research. 1998;47:25–34. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199801000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah JW, Johnston C. Parental social cognitions: Considerations in the acceptability of and engagement in behavioral parent training. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008;11:218–236. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers SA, Battistoni J. Proximal and distal correlates of adolescent mothers’ parenting attitudes. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Miller PA, Eisenberg N. The relation of empathy to aggressive and externalizing/antisocial behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:324–344. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The correlation of family management practices and delinquency. Child Development. 1984;55:1299–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus SE. Relations of parenting style and parental involvement with ninth-grade students’ achievement. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1994;14:250–267. [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Lopez E, Fields S, Kamboukos D, Duhig AM. Are fathers involved in pediatric psychology research and treatment? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:631–643. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan DK, Curtis P, Hunter WM, Black MM, Kotch JB, Bangdiwala, Landsverk J. LONGSCAN: A Consortium for longitudinal studies of maltreatment and the life course of children. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1998;3:275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Runyan D, Wattam C, Ikeda R, Hassan F, Ramiro L. Child abuse and neglect by parents and caregivers. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. Is it a different world to when you were growing up? Generational effects on social representations and child-rearing values. British Journal of Sociology. 2000;51:355–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin D. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel IE, McGillicuddy-DeLisi AV. Parent beliefs are cognitions: The dynamic belief systems model. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Being and becoming a parent. 2. Vol. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 485–501. [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. Parental mental health: Disruptions to parenting and outcomes for children. Child & Family Social Work. 2004;9:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Solis-Camara P, Romero MD. Coherence of parenting attitudes between parents and their children. Salud Mental. 1996;19:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Neilson EC. Early parenting: The roles of maltreatment, trauma symptoms, and future expectations. Manuscript under review. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN. Validity of a brief measure of parental affective attitudes in high-risk preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:945–955. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9621-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiehe VR. Empathy and narcissism in a sample of child abuse perpetrators and a comparison sample of foster parents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2001;27:541–555. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward L, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Gender differences in the transition to early parenthood. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:275–294. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Eisenberg N, Losoya S, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Guthrie IK, Shepard SA. The relations of parental warmth and positive expressiveness to children’s empathy-related responding and social functioning: A longitudinal study. Child Development. 2002;73:893–915. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotor AJ, Theodore AD, Runyan DK, Chang JJ, Laskey AL. Corporal punishment and physical abuse: Population-based trends for three- to 11-year-old children in the United States. Child Abuse Review. 2011;20:57–66. [Google Scholar]