Abstract

Background

There have been conflicting reports on how sagittal synostosis affects cranial vault volume (CVV) and which surgical approach best normalizes skull volume. In this study, we compare CVV and cranial index (CI) of children with sagittal synostosis (before and after surgery) to those of controls. We also compare the effect of repair type on surgical outcome.

Methods

CT scans of 32 children with sagittal synostosis and 61 age- and gender-matched controls were evaluated using previously validated segmentation software for CVV and CI. 16 cases underwent open surgery and 16 underwent endoscopic surgery. 27 cases had both preoperative and postoperative scans.

Results

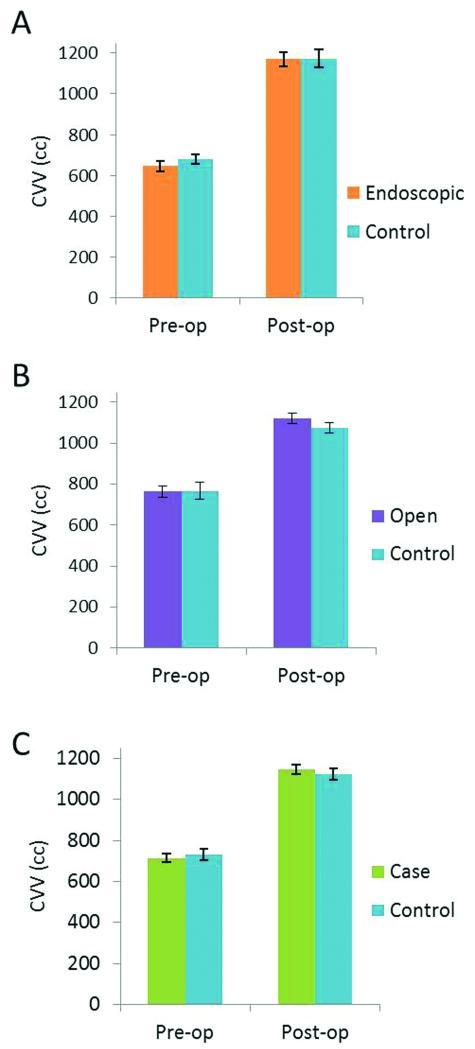

Age of subjects at CT scan ranged from 1-9 months preoperatively and 15-25 months postoperatively. Mean age difference between cases and matched controls was 5 days. The mean CVV of cases preoperatively was non-significantly (17cc) smaller than controls (p = 0.51). The mean CVV of postoperative children was non-significantly (24cc) larger than controls (p = 0.51). Adjusting for age and gender, there was no significant difference in CVV between open and endoscopic cases postoperatively (β = 48cc, p = 0.31). The mean CI increased 12% in both groups. There was no significant difference in mean postoperative CI (p = 0.18) between the two groups.

Conclusions

Preoperatively, children with sagittal synostosis have no significant difference in CVV compared to controls. Type of surgery does not seem to affect CI and CVV one year postoperatively. Both open and endoscopic procedures result in CVVs similar to controls.

Introduction

Sagittal synostosis is the most common type of craniosynostosis, affecting approximately 1 in 2500 live births (Jimenez DF and Barone CM, 1998; Panchal J and Uttchin V, 2003). It has long been believed that craniosynostosis presents an obstacle to normal growth of the cranial vault. The deformation is well-documented and surgical treatment is the standard of care. However, cranial vault volume (CVV) in patients with sagittal synostosis has been reported to be the same or higher than normal controls (Lee SS, et al., 2010, Heller JB, et al., 2008, Anderson PJ, et al., 2007, Netherway DJ, et al., 2005, Posnick JC, et al., 1995). Currently, it is unclear whether cognitive and functional deficits are due to primary brain abnormalities or altered cranial vault morphology (Kapp-Simon KA, et al., 2007; Kapp-Simon KA, et al. 2012; Sgouros S, 2005, Sgouros S, et al., 1999).

The surgical correction of sagittal synostosis has developed dramatically over the years. Over a century ago, strip craniectomies of the affected suture were initially advocated (Lannelongue M, 1890). However, it was discovered that these procedures had a high rate of reossification of the resected area with minimal improvement in head shape (Panchal J, et al., 1999). This led to widespread adoption of calvarial vault reconstruction techniques with intraoperative expansion of the cranial vault volume and immediate correction of the scaphocephaly.

Recently, an endoscopic approach has gained popularity (Jimenez DF and Barone CM, 1998). Although it bears similarity to the simple suturectomy originally advocated by Lannelongue, its success is based on rapid brain growth during early infancy and use of a postoperative molding helmet to optimize the shape of the calvarium. This endoscopic-assisted approach has been shown to be superior in terms of cost, operative time, amount of blood loss, and length of hospital stay (Mehta VA, et al., 2010, Abbott MM, et al., 2012).

Excellent cosmetic results have been documented in both open reconstruction and endoscopic-assisted techniques (Shah MN, et al., 2011, Fearon JA, et al., 2006, Gociman B, et al., 2012). However, there have been concerns that using molding helmet therapy postoperatively can lead to volume restriction.

In this study, we aim to compare CVV in children with sagittal synostosis to normal controls. We also compare CVV between patients that underwent open and endoscopic techniques to evaluate the possible effect of molding helmet therapy on CVV postoperatively. Cranial Index (CI) will also be measured as a marker of head shape morphology.

Methods

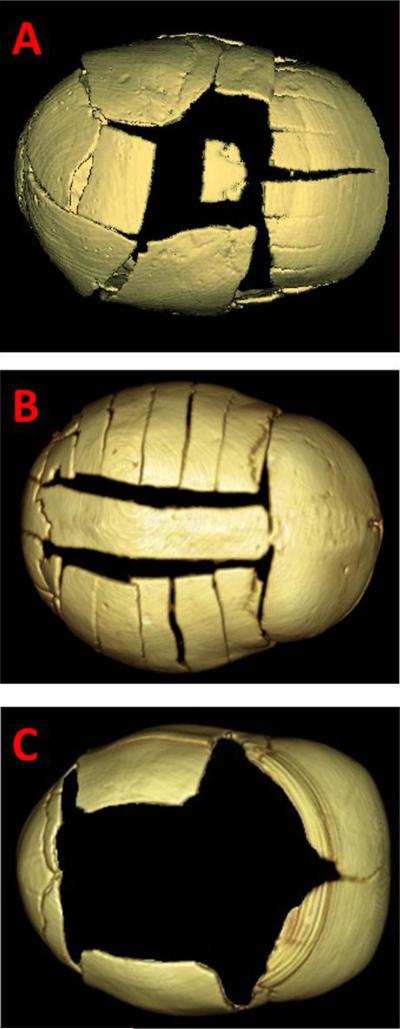

A retrospective review of patients seen at St. Louis Children’s Hospital from 1994 to 2012 was performed. Pre- and post-operative computed tomography (CT) data was obtained from subjects with nonsyndromic isolated sagittal synostosis. These cases were further classified by the type of surgery: open or endoscopic. Open operations included all non-endoscopic procedures: total calvarial reconstruction and modified pi procedures. These represented treatment modalities which are well-accepted by the surgical community, in contrast to the newer, endoscopic procedure. Three surgeons were involved in these procedures. Total calvarial vault reconstruction involves removal and reshaping of all skull segments: the frontal and occipital bones are osteotomized and remodeled, and a wide vertex ostectomy is then performed in addition to osteotomies in the temporal and parietal regions in a roughly H-shaped fashion to allow for biparietal expansion (Mathes, SJ and Hentz, VR, 2006). The modified pi technique performed at this institution involves creation of a central bone strut that is attached to the frontal bone and slightly shortened to decrease the anterior-posterior dimension. Free floating lateral barrel stave osteotomies are performed to allow for biparietal expansion. Finally, the endoscopic procedure involves a wide vertex ostectomy with lateral temporal and parietal ostectomies, similar to those described for total cranial vault reconstruction (Jimenez, DF and Barone, CM, 1994). However, no work on the frontal or occipital bones is performed. Growth is subsequently guided with use of a molding helmet (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Representative images of surgical repair techniques. A) Total calvarial vault reconstruction. B) Modified pi. C) Endoscopic repair.

CT data was also obtained from the same number of unaffected children matched by age and gender. Control subjects were seen for a variety of reasons (e.g. trauma, headaches). Those with a history of craniomaxillofacial fracture or surgery and those with congenital abnormalities affecting growth or development were excluded. All subjects whose CT data was compromised by poor resolution, incomplete data, or motion artifact were also excluded. All data were obtained according to approved Institutional Review Board protocols at Washington University in St. Louis.

Data Analysis

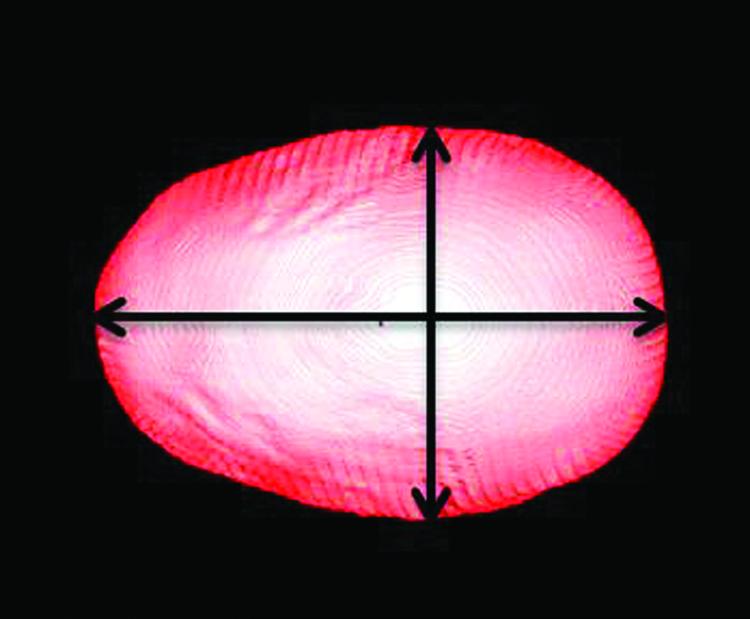

CT data were evaluated using Analyze 11.0 (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota) to measure the anterior-posterior (AP) length and bi-parietal (BP) width of the skull. Using the 3D volume render tool, head volumes were oriented to the Frankfort horizontal plane. The volume was edited to remove extraneous artifacts and/or tissues (e.g. auricles). A vertex view of soft tissue was used to establish measurements, and cranial index was calculated from these values (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Vertex view showing anterior-posterior and bi-parietal diameters used to determine CI.

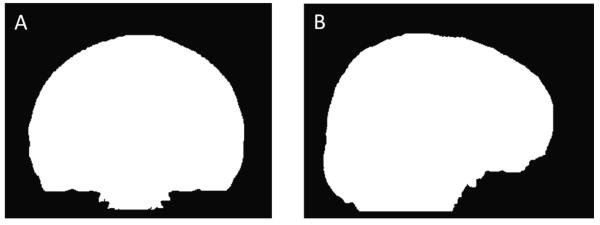

For cranial vault volume (CVV), CT data for each subject was loaded into Analyze software, a 3D reconstruction was made, and the information was transferred to MatLab R2011b (Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts). CVV was calculated using a script developed by the Electronic Radiology Laboratory at Washington University in St. Louis. Features of the program include orientation to hand-set landmarks, selection of skin and bone edges via threshold functions, and iterative erosions and dilations to isolate the cranial vault (Smith,KP; Politte, D; Reiker, G; Nolan, TS; Hildebolt, C; Mattson, C; Tucker, D; Prior, F; Turovets, S; Larson-Prior, LJ, 2013). Output included volume measurements as well as representative images of cranial vault (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Representative output of cranial vault volume segmentation. A) Coronal slice. B) Sagittal slice.

Two-tailed paired Student’s t-tests were used to compare matched cohorts. Regression analysis adjusting for age and gender was used to compare open and endoscopic groups. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics v20 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois) and Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington). Power calculations were generated using PS Power and Sample Size Calculations version 3.0 (Dupont WD, Plummer WD, 1990).

Results

Subjects

Preoperative CT data was obtained from 29 patients (mean age: 3 months; range: 1 to 9 months) and postoperative data from 32 patients (mean age: 17 months; range: 15 to 25 months). The age difference between paired cases and controls was no more than 12 days with a mean difference of 5 days. Endoscopic surgery subjects were considerably younger at time of preoperative scan than open surgery subjects (p < 0.001). [At our institution, typical age at repair is 2 to 4 months for the endoscopic-assisted technique and greater than 3 months of age for open procedures.] There was no significant difference in the ages of the two groups postoperatively (p = 0.977) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic details of all subject groups.

| Open Surgery | Endoscopic Surgery | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in months (mean ± s.e.m.*) |

Gender (M:F) |

Total | Age in months (mean ± s.e.m.) |

Gender (M:F) |

Total | |

| Pre-Op | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 12:5 | 17 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 9:3 | 12 |

| Control | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 12:5 | 17 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 9:3 | 12 |

|

| ||||||

| Post-Op | 17.5 ± 0.7 | 12:4 | 16 | 17.5 ± 0.6 | 13:3 | 16 |

| Control | 17.5 ± 0.7 | 12:4 | 16 | 17.5 ± 0.6 | 13:3 | 16 |

standard error of the mean

Cranial Vault Volume

Mean CVV’s for all cases and controls found no significant difference both preoperatively (p = 0.51) and postoperatively (p = 0.51). Likewise, there were no significant differences when comparing the open cohort to their matched controls (pre-op: p = 0.91, post-op: p = 0.13) or the endoscopic group to their matched controls (pre-op: p = 0.32, post-op: p = 0.97) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Pre- and post-operative comparisons of cranial vault volumes: A) All cases and controls. B) The open cohort and matched controls. C) The endoscopic cohort and matched controls.

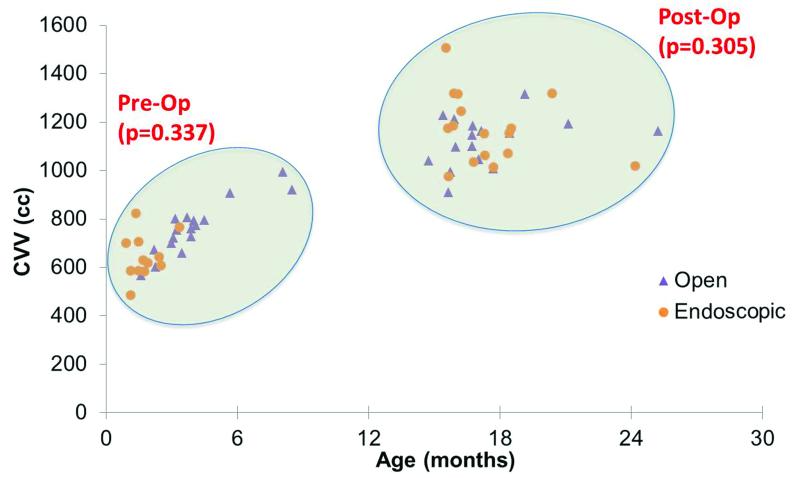

After adjusting for age and gender, the open and endoscopic groups had equivalent CVV’s preoperatively (β = 31cc, p = 0.34). A regression model accounted for most of the variation (r = 0.86). Comparison of postoperative data also showed no difference between open and endoscopic groups (β = 48cc, p = 0.31) (Fig. 5). Here, the model accounts for little of the variation in the results (r = 0.20). Using the natural logarithm of age in place of age improved the models and was used in both analyses. The logarithm of age had a highly significant effect preoperatively (β = 181, p < 0.001) but was not a significant factor postoperatively (β = -9, p = 0.96). After segregating the data by repair type, age was still not significantly correlated with CVV postoperatively (open repair: r = 0.37, p = 0.16; endoscopic repair: r = -0.46, p = 0.14). Gender was also not a significant predictor of CVV either pre- (β = 11, p = 0.75) or post-operatively (β = 10, p = 0.86).

Figure 5.

Scatterplot of cases both pre- and post-operatively demonstrate equivalent CVV’s post open and endoscopic repairs after adjusting for age and gender.

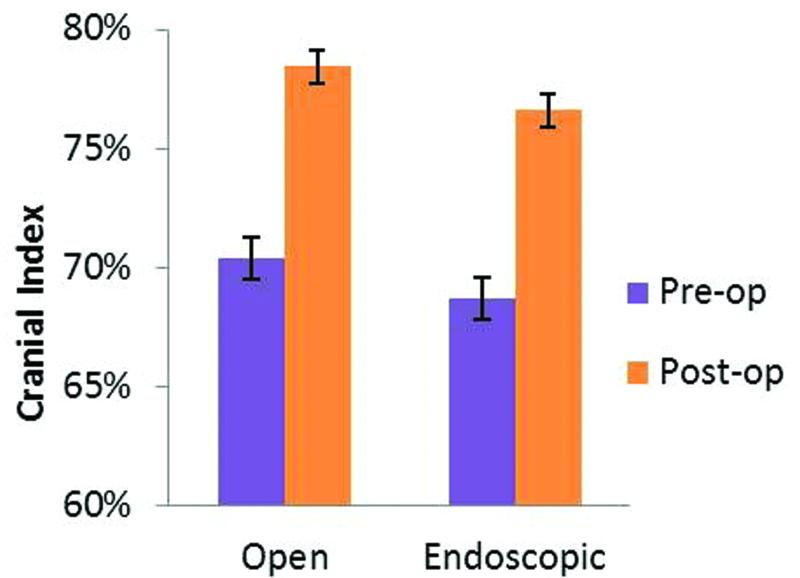

Cranial Index

Only cases with both pre- and post-operative CT scans were included in the analysis of cranial index (CI). There were 27 cases with such paired CTs. Fifteen had open reconstruction and 12 had endoscopic surgery. Preoperative CI was 70.4 ± 0.9% and 68.7 ± 1.1% for the open and endoscopic groups, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.25). One year postoperatively, 5 subjects had sub-normal CI (3 in the endoscopic and 2 in the open cohort). The mean CI’s of both the open and endoscopic pairs had increased by 12% and were within the normal range (78.4 ± 0.7% and 76.6 ± 1.3% respectively). Postoperative CI’s were equivalent in the two groups (p = 0.18) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Comparison of cranial index between open and endoscopic surgery. Values ≥75% were considered normal.

Discussion

Sagittal synostosis remains the most common type of craniosynostosis and numerous procedures have been advocated to correct this deformity. The two primary goals of craniosynostosis surgery are to improve skull shape and to release skull growth restriction. Cranial index has long been used to measure skull shape. Although it is limited in regard to its ability to measure cranial volume, it is simple, easily performed, and gives a general idea of the overall improvement in the shape of the skull. Issues of skull growth restriction have been more confusing. Cranial vault volume has been used as a means of understanding potential growth restriction. Despite a purported concern for increased intracranial pressure in craniosynostosis patients, individuals with sagittal synostosis have been reported to have the same or larger cranial vault volume than normal counterparts (Lee SS, et al., 2010, Heller JB, et al., 2008, Anderson PJ, et al., 2007, Netherway DJ, et al., 2005, Posnick JC, et al., 1995).

In this study, we separately analyzed the variables of cranial vault volume and cranial index in sagittal synostosis patients before and after surgery, comparing them to normal controls. Interestingly, we found no correlation between cranial vault volume and cranial index in the patients with sagittal synostosis preoperatively (p = 0.947). However, postoperatively, there was a significant positive correlation between cranial vault volume and cranial index (p = 0.013). The independent trajectories of these variables substantiate the dissociation of cosmetic form (as characterized by CI) from skull volume (as measured by CVV). Since surgical correction of sagittal synostosis is performed by increasing skull volume by widening the skull, a relationship between cranial volume and cranial index postoperatively is to be expected.

Cranial Vault Volume

The interpretation of cranial vault volume is complicated by the lack of a standard method for its measurement as well as the absence of a normative data standard. Independent studies have employed differing methods to measure cranial vault volume. Some have applied manual measurement techniques, which expose such analyses to potential for bias on the part of the evaluator. The measurements performed in this study were calculated using a script developed by the Electronic Radiology Laboratory at Washington University in St. Louis. This is an automated method, which eliminates bias and allows for standardized, easily repeated, and validated measurements. Additionally, a case-control model was utilized to offset the need for a normative data set, as all experimental patients had age- and gender-matched normal controls.

Our analysis reaffirmed other reports in the literature that cranial vault volumes of children with sagittal synostosis are not significantly different than those of normal children both pre- and one year post-operatively, regardless of surgical procedure performed for correction. Moreover, additional analyses were performed, comparing results from those who underwent open reconstruction to those treated by endoscopic techniques. It is worthy of note that critics of the newer endoscopic-assisted procedures have expressed concerns regarding the use of molding helmet therapy in patients with craniosynostosis. Specifically, concerns have been raised that helmet therapy has the potential for further restricting brain growth. While molding helmet therapy is designed not to cause compression, but rather guide expansion of the temporal and parietal regions, such a hypothesis has never been tested. We found no difference in the CVVs of open and endoscopically repaired subjects 1 year post-operatively, suggesting there is no discernible adverse effect in using molding helmet therapy in patients with craniosynostosis and that the results of both procedures are essentially equivalent.

Cranial Index

When assessing morphology using cranial index, we first noted that CI dramatically improves post-operatively when the patients with sagittal synostosis were evaluated overall. This finding is well-documented for open and endoscopic techniques. However, few studies have compared the two procedures to each other (Shah MN, et al., 2011). This analysis confirms previous literature noting that CI increases equivalently between open and endoscopic groups. Overall, both groups had an average increase in CI of roughly 12% with a mean result within the normal range. Furthermore, both groups also had a small subset of patients who did not attain a normal CI (3 in the endoscopic and 2 in the open cohort).

Limitations

Several limitations are identified in this study. Notably, due to relatively small sample size, minute differences cannot be delineated. This study was powered to detect a difference in CVV of 73cc between pre-operative cases and controls, and a difference in CI of 4% between post-operative patients in the open and endoscopic cohorts. Beyond this, in order to establish adequate power for the study, all open cases for reconstruction of sagittal synostosis were combined into a single group. This allowed for comparison of endoscopic procedures against an overall group of accepted, open procedures. However, it did not allow for comparison versus any specific technique (i.e. total calvarial vault reconstruction, modified pi). This study (as many others like it) would further benefit from a larger cohort. In an attempt to optimize data analysis, closely matched cases and controls were utilized.

Additionally, although we use cranial vault volume as a surrogate marker of cranial growth restriction, the neurologic relevance of cranial vault volume remains in question. Further studies are needed to elucidate the impact of both cranial size and morphology on neurologic development. Current literature discussing surgical effects on neurodevelopment is inconsistent (Kapp-Simon KA, Speltz ML, 2007). Given the similarity in CVV between cases and controls in multiple studies, further investigation is necessary to help elucidate the relationship between non-syndromic synostosis to cognitive, psychological, and behavioral development. Additional areas of study include examinations into the underlying brain morphology and possible regional differences between cases and controls.

It is also worthwhile to note that this study includes a limited age group, with typical age at endoscopic repair of approximately 2-3 months and open repair at 4-6 months. As a result, the findings may not be applicable to all patients with sagittal synostosis, especially those undergoing surgery at a later age.

Conclusions

Preoperatively, children with sagittal synostosis were not found to have significantly different cranial vault volumes when compared to normal controls. Furthermore, when the sagittal group was subdivided by surgical procedure (open vs endoscopic), there was no significant difference in cranial vault volume or cranial index between the two groups post-surgery, and both types of surgical correction resulted in cranial vault volumes similar to that of normal controls. This suggests that endoscopic correction of sagittal synostosis at 2-4 months provides equivalent results to that of open procedures performed at this institution.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation – Children’s Surgical Sciences Institute.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding Research reported in this publication was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR000448 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Children’s Discovery Institute, and Kirk Smith and Greg Reiker of the Electronic Radiology Laboratory for work under NIH grant R43-NS67726. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH.

References

- 1.Mathes SJ, Vincent RH. Plastic Surgery. 2nd Ed Saunders Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2006. Non-Syndromic Craniosynostosis. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jimenez DF, Barone CM. Calvarial defect reconstruction. Mo Med. 1994;91(4):183–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jimenez DF, Barone CM. Endoscopic craniectomy for early surgical correction of sagittal craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:77–81. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.1.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panchal J, Uttchin V. Management of craniosynostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:2032–2048. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000056839.94034.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SS, Duncan CC, Knoll BI, et al. Intracranial compartment volume changes in sagittal craniosynostosis patients: Influence of comprehensive cranioplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:187–196. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181dab5be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heller JB, Heller MM, Knoll B, et al. Intracranial volume and cephalic index outcomes for total calvarial reconstruction among nonsyndromic sagittal synostosis patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:187–195. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000293762.71115.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson PJ, Netherway DJ, McGlaughlin K, et al. Intracranial volume measurement of sagittal craniosynostosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:455–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Netherway DJ, Abbott AH, Anderson PJ, et al. Intracranial volume in patients with nonsyndromal craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:137–141. doi: 10.3171/ped.2005.103.2.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Posnick JC, Armstrong D, Bite U. Metopic and sagittal synostosis: intracranial volume measurements prior to and after cranio-orbital reshaping in childhood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:299–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapp-Simon KA, Speltz ML, Cunningham ML, et al. Neurodevelopment of children with single suture craniosynostosis: a review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:269–281. doi: 10.1007/s00381-006-0251-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sgouros S. Skull vault growth in craniosynostosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:861–870. doi: 10.1007/s00381-004-1112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sgouros S, Hockley AD, Goldin JH, et al. Intracranial volume change in craniosynostosis. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:617–625. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.4.0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lannelongue M. De la Craniectomie dans la Microcephalie. Compte-Rendu Acad Sci. 1890;110:1832. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta VA, Bettegowda C, Jallo GI, et al. The evolution of surgical management for craniosynostosis. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29:E5. doi: 10.3171/2010.9.FOCUS10204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott MM, Rogers GF, Proctor MR, et al. Cost of treating sagittal synostosis in the first year of life. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:88–93. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318240f965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah MN, Kane AA, Petersen JD, et al. Endoscopically assisted versus open repair of sagittal craniosynostosis: The St. Louis Children’s Hospital experience. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;8:165–170. doi: 10.3171/2011.5.PEDS1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fearon JA, McLaughlin EB, Kolar JC. Sagittal craniosynostosis: Surgical outcomes and long-term growth. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:532–541. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000200774.31311.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gociman B, Marengo J, Ying J, et al. Minimally invasive strip craniectomy for sagittal synostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:825–828. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824dbcd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Politte D, Reiker G, Nolan TS, et al. Automated measurement of skull circumference, cranial index, and braincase volume from pediatric computed tomography. 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE EMBS; Osaka, Japan. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc; 2013. pp. 3977–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridgway EB, Berry-Candelario J, Grondin RT, et al. The management of sagittal synostosis using endoscopic suturectomy and postoperative helmet therapy. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;7:620–626. doi: 10.3171/2011.3.PEDS10418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berry-Candelario J, Ridgway EB, Grondin RT, et al. Endoscope-assisted strip craniectomy and postoperative helmet therapy for treatment of craniosynostosis. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;31:E5. doi: 10.3171/2011.6.FOCUS1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapp-Simon KA, Collett BR, Barr-Schinzel MA, et al. Behavioral adjustment of toddler and preschool-aged children with single-suture craniosynostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(3):635–47. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc18b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panchal J, Marsh JL, Park TS, et al. Sagittal craniosynostosis outcome assessment for two methods and timings of intervention. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103(6):1574–84. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199905060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dupont WD, Plummer WD. Power and sample size calculations: A review and computer program. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1990;11:116–28. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90005-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]