Abstract

Study Objectives:

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a parasomnia characterized by motor activity during sleep with dream mentation. Aggressiveness has been considered a peculiar feature of dreams associated with RBD, despite normal score in aggressiveness scales during wakefulness. We aimed to measure daytime aggressiveness and analyze dream contents in a population of patients with Parkinson disease (PD) with and without RBD.

Design:

This is a single-center prospective observational study; it concerns the description of the clinical features of a medical disorder in a case series.

Setting:

The study was performed in the Department of Neurosciences of the Catholic University in Rome, Italy.

Patients:

Three groups of subjects were enrolled: patients with PD plus RBD, patients with PD without RBD, and healthy controls.

Interventions:

The diagnosis of RBD was determined clinically and confirmed by means of overnight, laboratory-based video-polysomnography. For the evaluation of diurnal aggressiveness, the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ) was used. The content of dreams was evaluated by means of the methods of Hall and Van De Castle.

Measurements and Results:

Patients with PD without RBD displayed higher levels of anger, and verbal and physical aggressiveness than patients with PD and RBD and controls. Patients with PD and RBD and controls did not differ in hostility.

Conclusions:

It can be hypothesized that a noradrenergic impairment at the level of the locus coeruleus could, at the same time, explain the presence of REM sleep behavior disorder, as well as the reduction of diurnal aggressiveness. This finding also suggests a role for REM sleep in regulating homeostasis of emotional brain function.

Citation:

Mariotti P, Quaranta D, Di Giacopo R, Bentivoglio AR, Mazza M, Martini A, Canestri J, Della Marca G. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: a window on the emotional world of Parkinson disease. SLEEP 2015;38(2):287–294.

Keywords: REM behavior disorder, Parkinson disease, aggressiveness, dreams, sleep

INTRODUCTION

Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a rapid eye movement (REM) sleep parasomnia, characterized by motor activity during sleep associated with dream mentation.1

Motor activity is related to an excess of muscle activity, caused by a loss of the REM sleep associated muscle atonia. Video-polysomnography (v-PSG) is required to establish the diagnosis of RBD by detecting REM sleep without atonia or more complex behaviors.1 The behaviors during RBD are various, complex, and nonstereotyped. Typically they include gesturing, kicking, punching, laughing, and talking. Sleep related injuries consequent to aggressive behavior are the reason for medical consultation in more than 75% of cases.2,3 Aggressiveness has been considered a peculiar feature of dreams associated with RBD; patients with RBD present a high proportion of aggressive contents in their dreams,4 despite normal levels of daytime aggressiveness.3,4 This condition can appear alone (idiopathic RBD), but it is commonly reported in patients with neurodegenerative disorders and there is strong evidence that RBD is a pathological stage in the development of neurodegenerative diseases.5,6

RBD seems to be the result of a dysfunction in the brainstem nuclei that modulate REM sleep and in their anatomical inputs from other regions. In humans, RBD has been described in neurological disorders sparing the brainstem but damaging the limbic system, the anterior thalamus, or posterior hypothalamus. In these disorders, RBD is probably caused by functional dysregulation of the brainstem REM sleep related structures rather than by their primary damage.7 Moreover, nonviolent elaborate behaviors that may also occur in RBD fill a large spectrum, including learned speeches and culture specific behaviors, suggesting they proceed from the activation of the cortex.8 In this way the distinction between the behaviors of “the acting out of dreams” and “the dreaming out of acts” remains an unsolved question.

RBD occurs in approximately 30–60% of patients with Parkinson disease (PD) and may precede the development of PD motor signs by 3 to 13 years.9,10 Therefore, it is suggested that many cases of idiopathic RBD may not be truly idiopathic, making it attractive to substitute the term “idiopathic” with “cryptogenetic.”9 Matching patient with RBD versus those without RBD and with idiopathic PD, Borek et al.11 described a higher percentage of violent dreams in patients with RBD. Conversely, a more recent study showed no differences in aggressiveness in dreams of patients with early-stage PD and with RBD versus those without RBD.12 In this context, it must be specified that anger is a normal emotion, and violence has, at its root, harm to another as its planned result; aggressiveness describes the method by which people go after their goals.

The aim of the current study was to evaluate daytime aggressiveness and nocturnal dream content in a population of patients with PD, and to compare diurnal and nocturnal aggressiveness between patients with PD with and without RBD.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

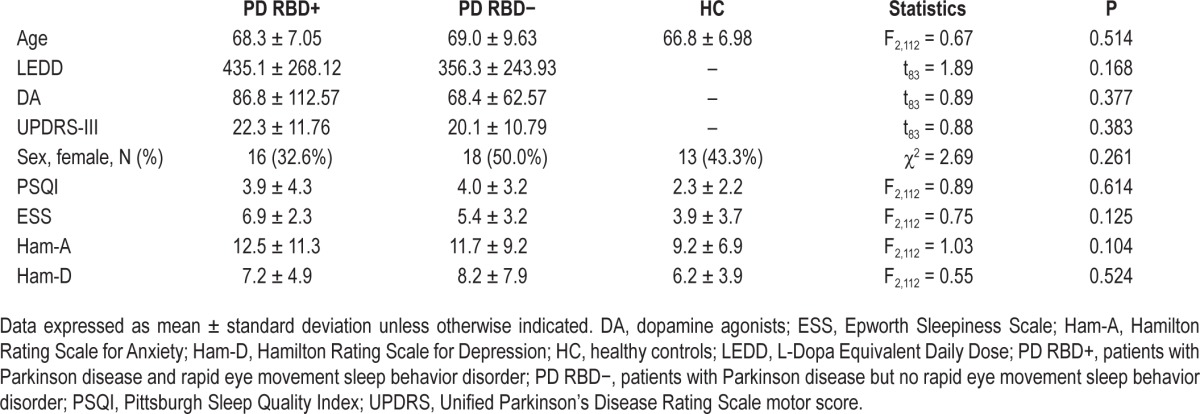

The sample included: 49 patients with PD and RBD (PD RBD+, 16 women and 33 men, mean age 68.3 ± 7.05 y), 36 patients affected by PD without RBD (PD RBD−, 18 women and 18 men, mean age 69.0 ± 9.63 y), and 30 healthy controls (HC, 18 women and 12 men, mean age 66.8 ± 9.98 y). Table 1 displays the demographic and clinical features of the three groups. The study groups were comparable as for age (P = 0.514) and sex distribution (P = 0.261); furthermore, PD RBD− and PD RBD+ patients were homogeneous for L-Dopa Equivalent Daily Dose13 (LEDD) (P = 0.168) and dopamine agonists (DA) (P = 0.377). As for PD RBD+, none of the patients enrolled was taking clonazepam or other sleep-active drugs at the time of the study.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features of the sample.

Study Design

The study was designed as a prospective open-label study enrolling all consecutive outpatients with PD seen at the Movement Disorder clinic in the period between January and June 2010. Entry criteria were: PD diagnosis according to UK Brain Bank criteria,14 and stable drug regimen and motor condition for at least 3 mo.

All referred patients underwent a standardized clinical examination. During the visit, the following data were retrieved for each patient: sex, age, disease duration, type and dose of medications used, Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale motor score (UPDRS-III),15 and occurrence of dyskinesias.

All consecutive patients who fulfilled the clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease, and agreed to participate in the study, were enrolled. Exclusion criteria were: orthostatic hypotension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, epilepsy, urinary obstruction and cardiac arrhythmias, treatment with anticholinergics or antidepressants, and deep brain stimulation therapy. Because benzodiazepines or central nervous system active drugs may affect dream content and recall, patient taking these drugs were not enrolled in the study.

To rule out the effect of anxiety, depression, or other psychiatric disorders, patients underwent a standardized psychiatric evaluation that included Mini-Mental State Examination (cutoff for inclusion: > 21); Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (Ham-A; cutoff > 17); Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D; cutoff > 7); and Structured Clinic Interviews for Disorders in Axis I and II (SCID-I and SCID-II).

To rule out the effects of antiparkinsonian treatment, LEDD13 were calculated for each patient enrolled. On the basis of the v-PSG the patients were divided into two groups: PD RBD− (PD without RBD) and PD RBD+ (PD with RBD). At the time of the study, no patient was treated for RBD. In patients with clinical indication, treatment for RBD was started immediately after conclusion of the study. Finally, 30 healthy volunteers were enrolled in the study to act as controls for patients with PD.

The protocol was carried out with adequate understanding and written consent of the patients and with the ethical approval of the local institutional Review Board.

Polysomnography

PSG was recorded in the sleep laboratory, for 2 consecutive nights. Sleep recording montage included electroencephalograph leads applied to the following locations: Fp1, Fp2, C3, C4, T3, T4, O1, O2; reference electrodes to the contralateral mastoid (M1); 2 electrooculography electrodes referred to the contra-lateral mastoid, surface electromyography (EMG) of submental muscles and anterior tibialis, electrocardiography, airflow, chest and abdominal movements, pulse oxymetry. Patients were not asked to keep a defined schedule, but were left free to follow their spontaneous sleep-wake cycle. Sleep recordings were analyzed visually and sleep stages were visually classified according to the criteria of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM).1 The diagnosis of RBD was determined using the clinical criteria established by the AASM,1 and confirmed by means of overnight, laboratory-based v-PSG. Atonia index and EMG activations were scored according to the methodology described by Ferri et al.16

Evaluation of Diurnal Aggressiveness

For the evaluation of diurnal aggressiveness, the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ)17 was adopted. The BPAQ represents a revision of the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI),18 which includes revisions of the response format and item content to improve clarity. Although, as with the Buss-Durkee scale, items for six a priori subscales were initially included in this measure, item-level factor analyses across three samples confirmed the presence of only four factors, involving physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility. The BPAQ has been adopted in a previous study on aggressiveness in patients with RBD by Fantini et al.19 To the best of our knowledge, the BPAQ questionnaire has not been previously administered to patients with PD.

Evaluation of Dream Content

The content of dreams was evaluated by means of the method of Hall and Van De Castle.20,21 Patients were asked to report their dreams in a diary, daily, in the morning, immediately after awakening. The dream collection period lasted 1 mo. According to this method, dream content was divided into 10 general categories: characters, social interactions, activities, striving (success and failure), misfortunes and good fortunes, emotions, physical surroundings, descriptive elements, food and eating, and elements from the past.21

Statistical Analysis

All measures of diurnal aggressiveness, as well as scores of the dream content analysis, were compared among the three groups: PD RBD−, PD RBD+, and HC. Means comparison of continuous variables were performed by means of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Scheffe test; thereafter, ANOVAs were performed to control comparisons for age, sex, UPDRS III score, LEDD, and DA. Differences of frequencies were assessed by means of χ2 with Yates continuity correction and Fisher exact test as required.

RESULTS

Aggressiveness

The mean scores obtained on the Aggressiveness Questionnaire by each group are shown in Table 2. The scores varied across the groups. There was a statistically significant difference between the three groups as shown by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.001); on Scheffe post hoc comparisons, the PD RBD− patients showed higher total aggressiveness than HC and PD RBD+ (P < 0.001 for both). On further analyses, significant differences were found for each of the Aggressiveness Questionnaire subitems (see Table 2). Patients affected by PD RBD− displayed higher levels of physical aggressiveness than PD RBD+ and HC (P < 0.001 in both cases on post hoc comparison). As for verbal aggressiveness, PD RBD− subjects showed higher levels than PD RBD+ (P = 0.020), but not when compared to HC (P = 0.117). On the “anger” subitem, PD RBD− patients obtained the higher mean score than both PD RBD+ and HC (P < 0.001 in both cases). Finally, PD RBD− patients showed higher hostility level than HC (P = 0.036), but not when compared to PD RBD+ (P = 0.168). PD RBD+ subjects and HC did not differ either in total Aggressiveness Questionnaire score (P = 0.697), or in physical aggressiveness (P = 0.864), verbal aggressiveness (P = 0.899), anger (P = 0.852), or hostility (P = 0.617). The effect of the Group variable was assessed by means of ANOVAs controlled for age, sex, UPDRS III score, LEDD, and DA. The analysis confirmed the independent effect of group as for total aggressiveness score (F2,107 = 11.36; P < 0.001), physical aggressiveness (F2,107 = 12.50; P < 0.001), verbal aggressiveness (F2,107 = 4.57; P = 0.012), and anger (F2,107 = 9.11; P < 0.001), but not for hostility (F2,107 = 2.00; P = 0.140). The effect of the Group variable was assessed by means of ANOVAs controlled for age, sex, UPDRS III score, LEDD, and DA. The analysis confirmed the independent effect of group as for total aggressiveness score (F2,107 = 11.36; P < 0.001), physical aggressiveness (F2,107 = 12.50; P < 0.001), verbal aggressiveness (F2,107 = 4.57; P = 0.012), and Anger (F2,107 = 9.11; P < 0.001), but not for hostility (F2,107 = 2.00; P = 0.140). No differences were observed in the scores for anxiety and depression (Ham-A and Ham-D, see Table 1).

Table 2.

Aggressiveness Questionnaire scores obtained by the three groups.

Dream Content Analysis

One hundred six dreams were collected and assessed by means of the Van De Castle scoring system. The overall frequency of dream recall was low (< 2 dreams per mo). During the 1-mo collection period, subjects affected by PD RBD+ were able to recall approximately the same number of dreams as patients with PD RBD− (60 versus 46), with 15/49 dreaming subjects in the PD RBD+ group and 8/36 subjects in the PD RBD− group (χ2 = 0.436; P = 0.509).

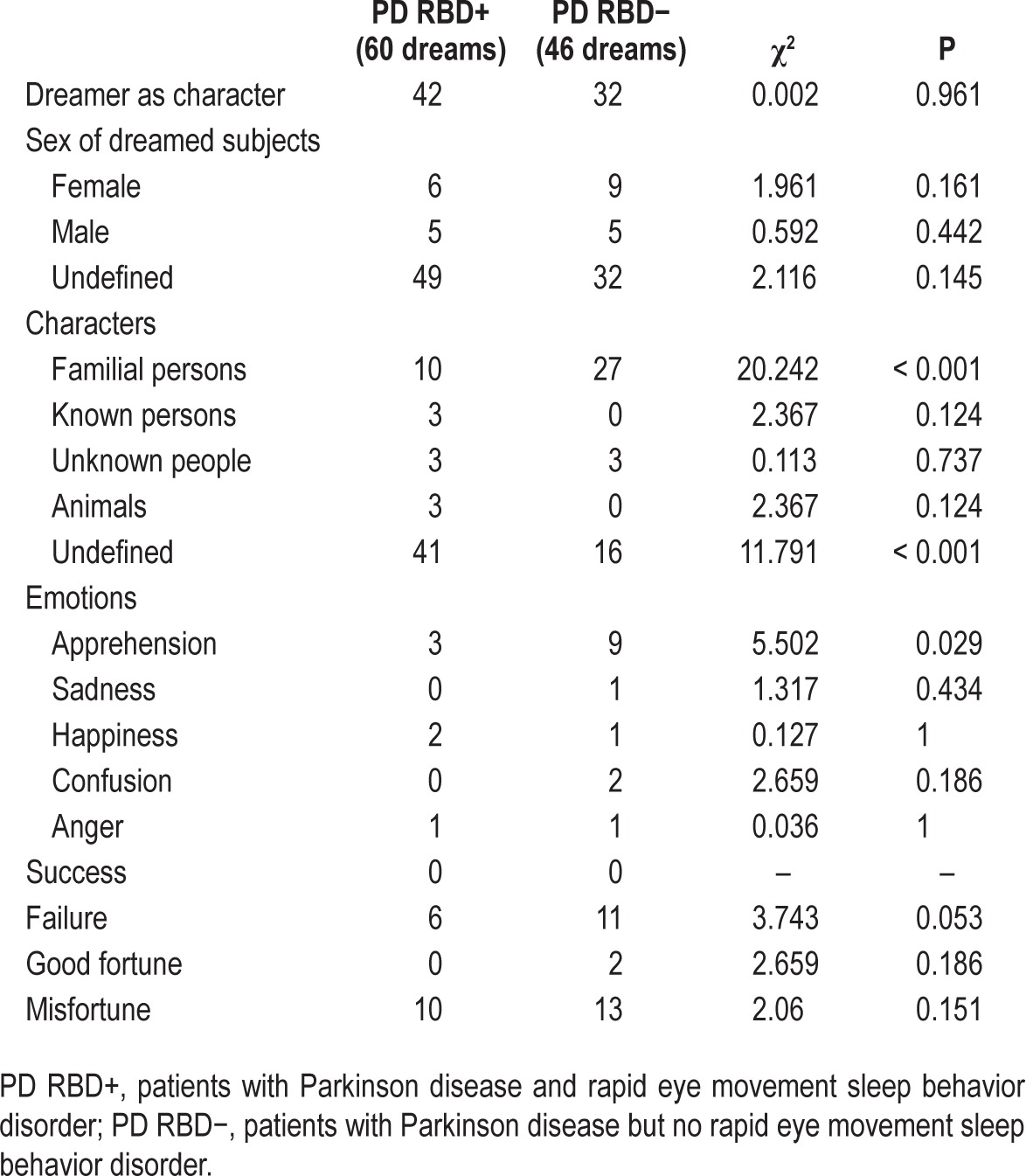

Table 3 displays the comparison of dream content between PD RBD+ and PD RBD− subjects. The presence of the dreamer as a character in the dreams was similar in the two groups (χ2 = 0.002; P = 0.961); moreover, the groups were homogeneous as for the sex of dreamed subjects (χ2 = 3.491; P = 0.322). A significant difference in the identity of dream characters was found, as PD RBD− subjects reported a higher frequency of family members (χ2 = 20.242.; P < 0.001), whereas it was mostly undefined in PD RBD+ (χ2 = 11.791; P < 0.001). In most cases, also the emotional content of the dreams was undefined; the only difference we observed was a higher frequency of apprehension in patients with PD RBD− (χ2 = 5.502; P = 0.029). Patients with PD RBD− also displayed a trend toward a higher frequency of failure dreams (χ2 = 3.743; P = 0.053). Finally, the groups were not different regarding the good fortune/misfortune dream content.

Table 3.

Comparison of dream content between PD RBD+ and PD RBD− subjects, Fisher exact test.

The dreams of PD RBD− and PD RBD+ subjects were also compared on the basis of their aggressive content. Because the number of dreams varied across the subjects, the mean dream aggressiveness for each subject was determined prior to the comparison of the two groups. Because of small sample size, comparison was performed by nonparametric statistics. The mean level of reported aggressiveness was higher in PD RBD+ than in PD RBD− subjects (respectively, 1.753 ± 2.625 versus 0.477 ± 0.495), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.549). Furthermore, PD RBD+ and PD RBD− patients displayed a similar frequency of dreams containing an aggressive element (that is, dreams on which an aggressiveness scale score different from 0 was assigned) (19/60 versus 13/46; χ2 = 1.14; P = 0.705). Table 4 reports the incidence of responses to each single item of the aggressiveness scale of Van de Castle system between the two groups; no statistically significant differences were found for any item.

Table 4.

Comparison of aggressive features frequency between the two groups.

No significant differences in PSG scores were observed between the groups, with the exception of the atonia index, which was lower in the PD RBD+ group (P < 0.002). Results of PSG scoring are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of PSG scoring.

DISCUSSION

The most relevant finding of this study is the marked difference in daytime aggressiveness in PD: patients without RBD showed higher total scores on the aggressiveness scales when compared to those with RBD. In particular, PD RBD− had higher levels of anger and physical and verbal aggressiveness with respect to PD RBD+. Conversely, there were no significant differences in the content of dreams between the two groups.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating daytime aggressiveness in a homogenous sample of patients with PD matching those with RBD versus those without RBD and controls. Overall, these results are consistent with the findings of Fantini et al.,4 who measured normal levels of daytime aggressiveness in patients with RBD.

Regarding the results of the dream content analysis, our data did not show significant differences between the RBD+ and RBD− groups. This is in accordance with the results reported by Bugalho and Paiva12 but it is partially in contrast with those reported by Borek et al.11 One hypothetic explanation for this discrepancy could be the different methods applied to evaluate dream content: in our study, as well as in that by Bugalho and Paiva,12 dreams were analyzed by means of the Halls and van de Castle system, whereas Borek et al.11 applied a different method.

A possible explanation for the differences in daytime aggressiveness could be linked to the clinical features of the disease, or to the dopaminergic treatment.

Aggressive diathesis can be conceptualized in terms of an imbalance between the “top-down” control or “brakes” provided by the orbital frontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex. Recently, the role of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in top-down control of aggression and more broadly of emotion has been confirmed.22

In PD, a variety of neurophysiological and neurochemical alterations can explain increased aggressiveness. Serotonin facilitates prefrontal cortical regions, such as the orbito-frontal cortex (OFC) and anterior cingulate cortex, that are involved in modulating and suppressing the emergence of aggressive behavior.23 Levels of brain serotonin transporter are lower in OFC24 of non- depressed patients with PD than in controls in all brain areas. Of course, a major role may be played by dopamine, which is involved in the initiation and performance of aggressive behaviors.25 These data parallel studies reporting reduced dopaminergic binding sites in amygdala, DLPFC, and OFC in early PD,26,27 involvement belonging to the associative and the limbic loop, suggesting that even in early PD stages, nonmotor circuits begin to be affected by the disease, and might contribute to the mental and behavioral impairment. Finally, noradrenaline facilitates the development of aggression,28 and its levels are increased in arousing situations, and it facilitates proactive and reactive aggression.29 Clinical studies of patients with PD indicate that the noradrenergic system may be affected before the dopaminergic system.30 During the earlier stages of the disorder, nonmotor preclinical symptoms of PD are observed, including hyposmia,31,32 RBD,3,33 or autonomic dysfunction,3,33 which can be attributed to neuropathological changes in the noradrenergic nervous system.30. The locus coeruleus (LC) is the major noradrenergic nucleus in the brainstem.34 Its neurons project directly to the whole brain, including the cerebral cortex and the spinal cord.34 Across the natural sleep-wake cycle, the noradrenergic neurons discharge at their highest rate during waking, decrease discharge during slow wave sleep, and cease firing during REM.35 The LC is involved in the pathogenesis of RBD. In 1965, Jouvet36 placed bilateral peri-LC lesions in cats and observed REM sleep without atonia and oneiric behavior that could only be explained by “acting out dreams”. Several further observations have confirmed the role of LC in this parasomnia.37 Structural changes in LC have been detected in patients with PD, and it has been demonstrated that these changes correlate with abnormally high muscle tone during REM sleep.38 Impaired LC function can cause acute, incidental RBD.39 Recently, some authors have hypothesized that repeated traumas may increase noradrenaline turnover, leading to its depletion in LC; this modification, in turn, could cause RBD.40

LC is involved, as well, in the regulation of aggressiveness. There is a positive correlation between noradrenergic neurotrans-mission and the natural aggressive response.41 These observations suggest an explanation for the peculiar difference in diurnal aggressiveness between patients with PD with and without RBD: it could be speculated that a noradrenergic impairment at the level of the LC could explain, at the same time, the presence of RBD, as well as the reduction of diurnal aggressiveness.

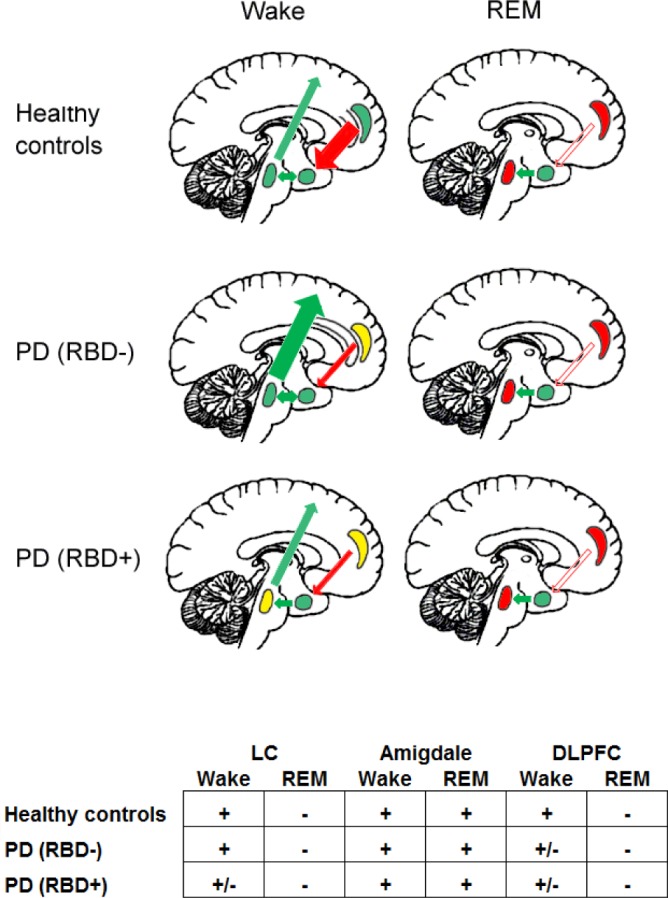

Another structure which plays a major role in the control of aggressiveness and anger is the amygdala.22 The amygdala has consistent, reciprocal connections with LC. These projections may underlie a role for the LC in processing the emotional valence of stimuli. The dysfunction of these connections between LC and amygdala could explain the difference between RBD+ and RBD− in anger and physical aggressiveness score. In fact, anger is the term for an emotion with corresponding feelings and physiological arousal,42 therefore anger and physical and verbal aggressiveness may be “arousal reactions mediated by subcortical structures”.17 Hostility, however, may be considered a predominantly cognitive process, controlled by cortical structures. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the modification of aggressiveness, during wakefulness and sleep, as measured in our patients, underlines an impairment of reciprocal LC-amygdala circuitry (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the reciprocal interactions between locus coeruleus (LC: oval shape), amygdala (circle shape), and prefrontal cortex (PFC: crescent moon shape) during wake and rapid eye movement (REM). Color code: green, normal activity; yellow, reduced activity; red, absent activity. Arrows: red, inhibitory effect; green, excitatory effect. The width of the arrow represent the intensity of the effect.

These differences in emotional behavior observed between RBD+ and RBD− subjects during wakefulness are abolished during REM sleep and dreaming. In fact, in the analysis of dream content, we have measured no differences in aggressive parameters between RBD+ and RBD− subjects. This suggests that overall aggressiveness and its subcomponents are modulated by different substrates during wake and sleep. During daytime, aggressiveness needs activation of the LC-amygdala circuitry, inhibited by the prefrontal cortex (PFC). This inhibitory effect of PFC is impaired in PD, resulting in increased aggressiveness.43 However, PD RBD+ patients, because of the impairment of the LC, have lower levels of diurnal aggressiveness. During REM sleep, when the activity of the LC-amygdala circuit is abolished (because of the shutdown of the LC), aggressiveness is reduced, and no difference can be observed between PD RBD+ and PD RBD− (Figure 1).

The interpretation of these data paves the way to reconsider RBD pathophysiology and require another paradigm, particularly with respect to the view of sleep and dreaming in particular as essentially a passive state. Because most behaviors described during RBD mimic aggressions, several authors suggested that RBD would proceed from archaic defense generators and other locomotor generators in the brainstem.4,33,44 Cases of complex non- violent behaviors suggest that they proceed from cortical activation.8 Iranzo et al.7 suggested that RBD is the result of a dysfunction in the brainstem nuclei that modulate REM sleep and their anatomical input from other regions. Moreover, in agreement with Iranzo et al.'s hypothesis,7 we believe that the loss of the physiologic REM-sleep associated muscle atonia enables us to have a direct window on dreaming. Nonviolent dreams and behavior are under-reported as they would less likely lead to arousal or injuries than violent dreams and behavior. These would be less likely to cause arousal or injure the patients or their cosleepers than violent behaviors.8 In this way a significant proportion of patients (8–35%) with RBD are not aware of having dream-enacting behaviors, and a significant proportion of patients (50–75%) with RBD do not recall unpleasant dreams.7 Similar findings have been recently reported by D'Agostino et al.,45 who suggested that the anecdotal view that dreams of patients with RBD contain more aggressive elements than those of the general population may not be confirmed. These authors have suggested that the “mild” waking temperament could be interpreted as an early subtle sign of the apathy and passivity that is commonly described in the context of neurodegenerative disorders. We believe that these behavioral modifications could be caused by impairment of arousal-related brainstem structures, and particularly to the LC. According to Walker and Van Der Helm,46 REM sleep may allow reactivation of previously acquired affective experiences, through the activation of limbic and paralimbic structures, including the hippocampus and the amygdala. Particularly during REM sleep, this would occur when the activity of subcortical to cortical aminergic pathways is decreased,47 mainly the noradrenergic input from the LC.

The main limitations of this study are the low frequency of recalled dreaming, and the possible confounding effects caused by pharmacological treatment of patients with PD versus controls. Previous research has indicated that dream recall may be influenced by a variety of factors, including personality, openness to experience, creativity, visual memory, attitude toward dreams, and also sleep behavior: sleep duration and cognitive functioning immediately upon awakening (sleep inertia). These things show substantial covariance with the interindividual differences in dream recall frequency.48 In our patients, the low frequency of dream recall may be caused by a sum of factors, including old age, prevalence of male sex, and sleep disruption.49 Also, the degree of compliance with dream recording was not checked. All our patients, both RBD+ and RBD−, were taking dopaminergic therapy at the time of the study, but none was taking drugs for RBD. Moreover, our RBD+ and RBD− groups did not differ in the severity of the clinical symptoms, disease duration, and amount of treatment (expressed as LEDD). Nevertheless, the potential drug effect on aggression in this study could not be completely excluded: drug-free, newly diagnosed cases should be considered. Finally, a further limitation was the lack of dream content analysis in the control group.

Within these limits, the results of our study do not confirm that dream content in PD RBD+ is characterized by increased levels of aggressiveness. It can be hypothesized that a noradrenergic impairment at the level of the LC could, at the same time, explain the presence of RBD, as well as the reduction of diurnal aggressiveness as compared to PD RBD−. This finding also supports the role for REM sleep in regulating homeostasis of emotional brain function.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This study was supported by a grant from the Research Advisory Board (RAB) of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA) on the project “REM Sleep Behaviour Disorder: A Model for Dream Analysis in Human Subjects.” The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan SF. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. The AASM manual for scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olson EJ, Boeve BF, Silber MH. Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder: demographic, clinical and laboratory findings in 93 cases. Brain. 2000;123:331–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. REM sleep behavior disorder: clinical, developmental, and neuroscience perspectives 16 years after its formal identification in SLEEP. Sleep. 2002;25:120–38. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fantini ML, Corona A, Clerici S, Ferini-Strambi L. Aggressive dream content without daytime aggressiveness in REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology. 2005;65:1010–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000179346.39655.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Saper CB, et al. Pathophysiology of REM sleep behaviour disorder and relevance to neurodegenerative disease. Brain. 2007;130:2770–88. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagnon JF, Postuma RB, Mazza S, Doyon J, Montplaisir J. Rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder and neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:424–32. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iranzo A, Santamaria J, Tolosa E. The clinical and pathophysiological relevance of REM sleep behavior disorder in neurodegenerative diseases. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:385–401. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oudiette D, De Cock VC, Lavault S, Leu S, Vidailhet M, Arnulf I. Nonviolent elaborate behaviors may also occur in REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology. 2009;72:551–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341936.78678.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comella CL, Nardine TM, Diederich NJ, Stebbins GT. Sleep-related violence, injury, and REM sleep behavior disorder in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1998;51:526–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagnon JF, Bedard MA, Fantini ML, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2002;59:585–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borek LL, Kohn R, Friedman JH. Phenomenology of dreams in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22:198–202. doi: 10.1002/mds.21255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bugalho P, Paiva T. Dream features in the early stages of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:1613–9. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, Rick C, Gray R, Clarke CE. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2649–53. doi: 10.1002/mds.23429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:33–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Hilten JJ, van der Zwan AD, Zwinderman AH, Roos RA. Rating impairment and disability in Parkinson's disease: evaluation of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale. Mov Disord. 1994;9:84–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferri R, Marelli S, Cosentino FI, Rundo F, Ferini-Strambi L, Zucconi M. Night-to-night variability of automatic quantitative parameters of the chin EMG amplitude (Atonia Index) in REM sleep behavior disorder. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:253–8. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:452–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buss AH, Durkee A. An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. J Consult Psychol. 1957;21:343–9. doi: 10.1037/h0046900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fantini ML, Ferini-Strambi L, Montplaisir J. Idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder: toward a better nosologic definition. Neurology. 2005;64:780–6. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152878.79429.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall CS, Domhoff GW, Blick KA, Weesner KE. The dreams of college men and women in 1950 and 1980: a comparison of dream contents and sex differences. Sleep. 1982;5:188–94. doi: 10.1093/sleep/5.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall CS, Van de Castle R. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1966. The content analysis of dreams. [Google Scholar]

- 22.New AS, Hazlett EA, Newmark RE, et al. Laboratory induced aggression: a positron emission tomography study of aggressive individuals with borderline personality disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:1107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siever LJ. Neurobiology of aggression and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:429–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guttman M, Boileau I, Warsh J, et al. Brain serotonin transporter binding in non-depressed patients with Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:523–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Almeida RM, Ferrari PF, Parmigiani S, Miczek KA. Escalated aggressive behavior: dopamine, serotonin and GABA. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berti V, Polito C, Ramat S, et al. Brain metabolic correlates of dopaminergic degeneration in de novo idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;37:537–44. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouchi Y, Yoshikawa E, Okada H, et al. Alterations in binding site density of dopamine transporter in the striatum, orbitofrontal cortex, and amygdala in early Parkinson's disease: compartment analysis for beta-CFT binding with positron emission tomography. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:601–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miczek KA, Fish EW, De Bold JF, De Almeida RM. Social and neural determinants of aggressive behavior: pharmacotherapeutic targets at serotonin, dopamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid systems. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:434–58. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegel A, Victoroff J. Understanding human aggression: new insights from neuroscience. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32:209–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMillan PJ, White SS, Franklin A, et al. Differential response of the central noradrenergic nervous system to the loss of locus coeruleus neurons in Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2010;1373:240–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berendse HW, Booij J, Francot CM, et al. Subclinical dopaminergic dysfunction in asymptomatic Parkinson's disease patients' relatives with a decreased sense of smell. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:34–41. doi: 10.1002/ana.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ponsen MM, Stoffers D, Booij J, van Eck-Smit BL, Wolters E, Berendse HW. Idiopathic hyposmia as a preclinical sign of Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:173–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Parisi JE, et al. Synucleinopathy pathology and REM sleep behavior disorder plus dementia or parkinsonism. Neurology. 2003;61:40–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073619.94467.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones BE. Arousal systems. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s438–51. doi: 10.2741/1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 1981;1:876–86. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jouvet M. Paradoxical sleep--a study of its nature and mechanisms. Prog Brain Res. 1965;18:20–62. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dugger BN, Murray ME, Boeve BF, et al. Neuropathological analysis of brainstem cholinergic and catecholaminergic nuclei in relation to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;38:142–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2011.01203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia-Lorenzo D, Longo-Dos Santos C, Ewenczyk C, et al. The coeruleus/subcoeruleus complex in rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorders in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2013;136:2120–9. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manni R, Ratti PL, Terzaghi M. Secondary “incidental” REM sleep behavior disorder: do we ever think of it? Sleep Med. 2012;12:S50–3. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Husain AM, Miller PP, Carwile ST. Rem sleep behavior disorder: potential relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18:148–57. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haller J, Kruk R. Neuroendocrine stress responses and aggression. In: Mattson MP, editor. Neurobiology of aggression. Understanding and preventing violence. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spielberger CD, Johnson EH, Russell SF, Crane RJ, Jacobs GA, de Worn TI. The experience and expression of anger: construction and validation of an anger expression scale. In: Chesney MA, Rosenman RH, editors. Anger and hostility in cardiovascular and behavioral disorders. New York: Hemisphere/McGraw-Hill; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Todes CJ, Lees AJ. The pre-morbid personality of patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48:97–100. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.48.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tassinari CA, Rubboli G, Gardella E, et al. Central pattern generators for a common semiology in fronto-limbic seizures and in parasomnias. A neuroethologic approach. Neurol Sci. 2005;26:s225–32. doi: 10.1007/s10072-005-0492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.D'Agostino A, Manni R, Limosani I, Terzaghi M, Cavallotti S, Scarone S. Challenging the myth of REM sleep behavior disorder: no evidence of heightened aggressiveness in dreams. Sleep Med. 2012;13:714–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walker MP, van der Helm E. Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:731–48. doi: 10.1037/a0016570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pace-Schott EF, Hobson JA. The neurobiology of sleep: genetics, cellular physiology and subcortical networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:591–605. doi: 10.1038/nrn895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schredl M, Wittmann L, Ciric P, Gotz S. Factors of home dream recall: a structural equation model. J Sleep Res. 2003;12:133–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2003.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schredl M, Reinhard I. Dream recall, dream length, and sleep duration: state or trait factor. Percep Motor Skills. 2008;106:633–6. doi: 10.2466/pms.106.2.633-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]