Abstract

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most prevalent cause of preventable blindness worldwide and a major reason for infectious infertility in females. Several bacterial factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of C. trachomatis. Combining structural and mutational analysis, we have shown that the proteolytic function of CT441 depends on a conserved Ser/Lys/Gln catalytic triad and a functional substrate-binding site within a flexible PDZ (postsynaptic density of 95 kDa, discs large, and zonula occludens) domain. Previously, it has been suggested that CT441 is involved in modulating estrogen signaling responses of the host cell. Our results show that although in vitro CT441 exhibits proteolytic activity against SRAP1, a coactivator of estrogen receptor α, CT441-mediated SRAP1 degradation is not observed during the intracellular developmental cycle before host cells are lysed and infectious chlamydiae are released. Most compellingly, we have newly identified a chaperone activity of CT441, indicating a role of CT441 in prokaryotic protein quality control processes.

INTRODUCTION

Infections with the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis are among the most common sexually transmitted diseases worldwide, with approximately 1.5 million reported cases in the United States in 2012 (1). While most of the acute infections of the lower urogenital tract are asymptomatic and remain unrecognized by the affected people, ascending infections in females often result in severe chronic sequelae, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility (2). Despite its clinical relevance, many aspects of the underlying virulence mechanisms have not been elucidated so far.

As for other pathogens, infectivity and the propensity to manipulate host immune responses largely depend on the repertoire of pathogenicity factors. The most extensively studied effector protein in Chlamydia research is CPAF (chlamydial protease-like activity factor), which has been reported to degrade a broad spectrum of host cell proteins (3). However, it has been shown that the observed degradation of many previously identified CPAF substrates is an artifact of the protein isolation process (4), and thus whether CPAF actively degrades host cell proteins during the intracellular developmental cycle is a controversial subject of discussion.

A second chlamydial protease, designated CT441 for C. trachomatis, shares significant amino acid sequence similarity with tail-specific proteases (Tsps) from other species (e.g., 25% identity with Tsp from Escherichia coli) and was first proposed by Lad et al. to interfere with host antimicrobial and inflammatory responses (5, 6); however, in later reports, a role of CT441 and CPAF in the cleavage of NF-κB during the chlamydial infection has been put into question (4, 7). Unique regions that show no similarities to any characterized domain are present at the N terminus of Tsp proteins. E. coli Tsp cleaves substrate proteins labeled with a C-terminal ssrA-encoded peptide tag (small stable RNA A) and is involved in protein quality control in the periplasm (8). Borth et al. observed that CT441 modulates the estrogen signaling pathway of the host cell by interaction with host-derived SRAP1 (steroid receptor RNA activator protein 1), a coactivator of estrogen receptor α (ERα) (9). The interaction between CT441 and SRAP1, mediated via the PDZ domain of CT441, was confirmed by glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown and intracellular colocalization experiments. Lysates of eukaryotic cells transfected with CT441 showed proteolytic cleavage of endogenous p65, yet no degradation of SRAP1 was observed. However, when analyzed in a yeast system, coactivation of ERα by SRAP1 was strongly diminished in the presence of CT441 or its isolated PDZ domain (9).

To elucidate the role of CT441 in C. trachomatis infections, we combined analysis of the protein structure using X-ray crystallography with functional assays on protein-protein interactions and CT441 biological activities. While the protease activity of recombinant CT441 in vitro could not be confirmed during the intracellular C. trachomatis developmental cycle, a completely novel chaperone function for CT441 was detected.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein production and purification of CT441 proteins.

Details on recombinant production and purification of CT441 from C. trachomatis L2/Bu/434 will be given in a future publication. Briefly, N-terminally His-tagged CT441 proteins lacking the signal sequence were produced in E. coli C43(DE3) cells, purified by nickel affinity and size exclusion chromatography (SEC), and concentrated to 2.5 to 10 mg/ml in 20 mM Tris–150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. For crystallization, a proteolytically inactive variant was used (CT441S455A [CT441°]); the His tag was removed by human rhinovirus 3C protease cleavage. Site-directed mutagenesis (for CT441°, CT441K481A, CT441Q485A, and CT441I254W) was performed using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene); domain variants (CT441ΔDUF3340, CT441NTD&PDZ, and CT441NTD) were generated using standard PCR-based cloning techniques (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Production and purification of SRAP1.

N-terminally His-tagged SRAP1 was produced in E. coli BL21(DE3) CodonPlus-RIL (Stratagene) and purified as described for CT441. After removal of the His tag and SEC, SRAP1-containing fractions were concentrated to 2.5 mg/ml in 20 mM Tris–150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. Note that the C terminus of our SRAP1 construct deviates from that used by Borth et al. (9) to reflect the updated DNA sequence (AF293026.1) at NCBI.

Crystallization, diffraction data collection, and structure determination.

Equal volumes (5 μl) of protein (2.5 mg/ml) and crystallization solution (100 mM morpholineethanesulfonic acid [MES] [pH 6.0], 100 mM MnSO4, 5% [vol/vol] polyethylene glycol [PEG] 6000, and 6% [vol/vol] ethylene glycol) were mixed and equilibrated against 500 μl reservoir solution (1.5 M NaCl). Crystals grew within 2 to 4 weeks at 20°C to a final size of 0.13 mm by 0.11 mm by 0.08 mm. Prior to diffraction experiments, crystals were directly transferred into cryoprotection solution (70 mM MES [pH 6.0], 140 mM MnSO4, 3.5% [vol/vol] PEG 6000, and 34.5% [vol/vol] ethylene glycol), mounted in CryoLoops (Hampton Research), and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. For single anomalous dispersion (SAD) experiments, crystals were soaked in solutions containing 500 mM NaI or Ta6Br12 (Jena Bioscience) according to the manufacturer's protocol for 1 h to 24 h at 4°C. X-ray diffraction data were collected at BESSY (Berlin, Germany), integrated with the MOSFLM (10) or XDS (11) software program, and scaled and merged with the program SCALA (12). Crystallographic phase information based on SAD data was determined using the Phenix program suite (13). A preliminary model was built by using Phenix AutoBuild (14) and Buccaneer (15) software and subsequently manually completed and refined using the programs Coot (16) and Phenix (17), respectively. Grouped B-factor refinement as implemented in the phenix.refine program was used to account for the flexible N-terminal domains (NTDs) of molecules A and C. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Protease activity assay.

Protease activity of CT441 proteins (5 μM) was determined using the fluorogenic reporter peptide DPMFKLV–7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (DPMFKLV-AMC; 500 µM) in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris and 150 mM NaCl, pH 9.5) at 37°C using excitation/emission wavelengths of 360 nm/460 nm. Assays were performed in triplicate, and data were analyzed using PRISM (GraphPad Software).

Cleavage of SRAP1 by cell lysates, recombinant CT441, or within infected cells.

HEK293 cells (4 × 105 cells/well) were seeded on poly-l-lysine-pretreated 6-well plates and cultivated for 24 h in RPMI 1640 (10% fetal calf serum [FCS]). After C. trachomatis L2/Bu/434 infection (0.3 inclusion-forming units [IFU]/cell), cells were harvested in 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/well at time points 8 h, 24 h, 32 h, and 48 h postinfection (p.i.). Cell lysates (22.5 μl) were incubated with recombinant SRAP1 (6.25 μg) for 4 h at 37°C.

For SRAP1 cleavage by recombinant CT441, purified SRAP1 (6.25 μg) was incubated with CT441 (5.2 μg) at 37°C or 4°C. Samples incubated at 37°C were collected after 5 min, 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h; samples incubated at 4°C were collected after 6 h and 24 h. As a control, CT441° was incubated with SRAP1 for 4 h or 24 h.

For SRAP1 production in eukaryotic host cells, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with a SRAP1-encoding plasmid (4 μg/well; Origene) 24 h after seeding, using TurboFect (Thermo Scientific) in transfection medium (Opti-MEM), followed by medium exchange to RPMI 1640 (5% FCS) 5 h posttransfection. The resulting HEK293SRAP1+ cells were collected in PBS (200 μl/well) 48 h after transfection and lysed. The cell lysate (22.5 μl) was incubated with recombinant CT441 (5.2 μg) for 4 h at 37°C.

For analysis of SRAP1 degradation during the infection, HEK293SRAP1+ cells (4 × 105 cells/well) were infected with C. trachomatis L2/Bu/434 (0.3 IFU/cell) and harvested in 200 μl 8 M urea-benzonase solution/well at time points 8 h, 24 h, 32 h, and 48 h p.i. according to the protocol used by Chen et al. (4).

Immunofluorescence staining of SRAP1 and CT441 in HEK293 cells.

HEK293SRAP1+ cells (4 × 104 cells/well) grown on cover slides and infected with C. trachomatis (0.2 IFU/cell) were fixed with methanol (MeOH) (32 h or 48 h p.i.). Intracellular localization of proteins was visualized using the primary antibodies mouse anti-CT441 (1:1,000; provided by G. Zhong) and rabbit anti-SRAP1 (1:250; Santa Cruz), as well as the corresponding Cy5–donkey anti-mouse (1:250, Cell Signaling) and FITC–goat anti-rabbit (1:100; Cell Signaling) secondary antibodies. Immunofluorescence images were collected using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM Meta 510; Zeiss). For fluorescence signal profile analysis, the Axiovision LE software program (Zeiss) was used. Viability of HEK293SRAP1+ cells (4 × 105 cells/well) was monitored 8 h, 24 h, 32 h, and 48 h p.i. with C. trachomatis (0.9 IFU/cell) using the Pierce lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assay kit (six independent experiments). Results were correlated to the LDH activity determined after complete lysis of uninfected cells with the supplied lysis buffer. Statistical analysis was performed using the PRISM program (GraphPad Software).

Chaperone activity assay.

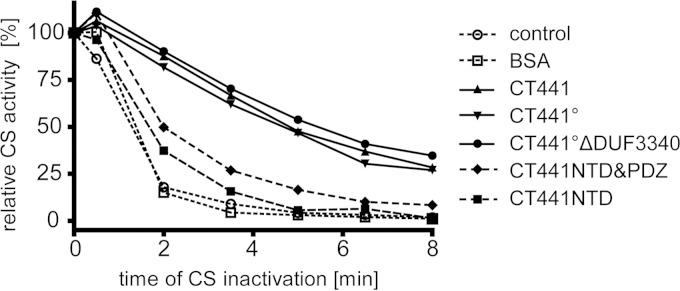

The chaperone activity assay was modified from the method of Buchner et al. (18). Samples were incubated in HEPES (pH 7.5) for 0.5 to 8 min at 43°C with or without 20 μM CT441 proteins (20 μM His-tagged CT441, CT441°, CT441ΔDUF3340, CT441NTD&PDZ, or CT441NTD) or bovine serum albumin (BSA). After heat treatment, residual citrate synthase (CS) activity was determined at 20°C. Results presented in Fig. 6 are based on three independent experiments. For statistical analysis, the 2-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) significance test as implemented in PRISM (GraphPad Software) was used.

FIG 6.

CT441 has chaperone activity. Citrate synthase (CS) was heat inactivated for the indicated period of time in the presence of CT441 proteins or bovine serum albumin (BSA), and residual CS activity was determined. CT441, CT441°, and CT441°ΔDUF3340 show pronounced chaperone activity (P < 0.05 between 2 min and 8 min); the truncated variant CT441NTD&PDZ (P < 0.05 between 2 min and 3.5 min) or CT441NTD (P < 0.01 at 2 min), lacking protease or protease and the PDZ domain, respectively, display a reduced protective effect. CS without any additional protein was used as a control. As expected, BSA did not affect CS activity. For statistical analysis, the 2-way ANOVA method based on results from three independent measurements was used.

Protein structure accession number.

The atomic coordinates determined in this work have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB identifier 4QL6).

RESULTS

CT441 is a serine protease with a catalytic triad comprising three distinct domains.

To gain detailed insights into the structural organization and its catalytic mechanism, the three-dimensional structure of CT441 was determined by X-ray crystallography to a resolution of 3.0 Å (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). CT441 has a modular domain organization comprising an N-terminal domain (NTD) (residues 22 to 242), a PDZ domain (residues 243 to 341), and a C-terminal protease domain (CTD) (residues 342 to 649), which harbors the catalytic residues S455 and K481 (Fig. 1A). The NTD and CTD are well defined by electron density in all three CT441 molecules of the asymmetric unit, although average temperature factors for atoms of the NTD in molecules A and C indicate a high degree of flexibility (see Table S1). No electron density was observed for the PDZ domain, since it is loosely attached to the NTD and the CTD by long flexible loops which allow for multiple positions of the domain in the crystal lattice. SDS-PAGE analysis of dissolved CT441 crystals confirmed that the PDZ domain was not degraded or removed during the crystallization process (see Fig. S1).

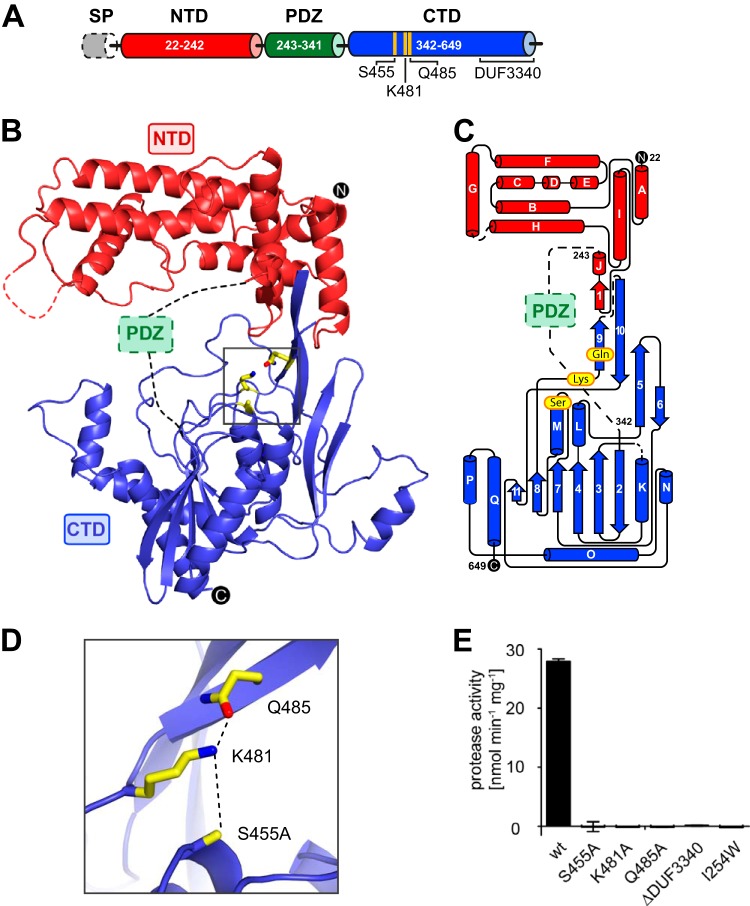

FIG 1.

Structural architecture and proteolytic site of CT441. (A) Domain organization of CT441 with signal peptide (SP), N-terminal domain (NTD), PDZ domain (green), and C-terminal domain (CTD). Residues of the proteolytic site and the previously annotated DUF3340 subdomain are indicated. (B) Overall structure of CT441 in ribbon representation with residues of the proteolytic site shown as sticks (yellow). The PDZ domain and several loop regions were too flexible to be modeled into electron density, and their approximate positions are indicated by a green box and dashed lines, respectively. (C) Topology diagram of CT441 with residues of the proteolytic site and domain boundaries indicated. (D) Closeup view of catalytic triad residues shown as sticks. Dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds aligning the active-site residues. Since the inactive CT441S455A (CT441°) variant was used for crystallization, the hydrogen bond to K481 is based on molecular modeling. (E) Proteolytic activity of CT441 variants. Substitution of catalytic triad residues (S455A, K481A, and Q485A), deletion of the DUF3340 domain (ΔDUF3340), or disruption of the substrate binding site of the PDZ domain (I254W) prohibit cleavage of the fluorogenic reporter peptide DPMFKLV-AMC. wt, wild type.

The NTD displays a novel fold consisting of 10 α-helices (A to J) and a short β-strand (β1). Helices B to F form a parallel helix-bundle-like structure which packs against helices A and I on one end and against helix G on the other end. Helix J and β-strand 1 are located in the interface region between the NTD and the CTD (Fig. 1B and C). A DALI search (19) revealed no structural homologs of the NTD. The CTD of CT441 contains 7 α-helices (K to Q) and 10 β-strands (2 to 11), forming two β-sheets. Whereas one β-sheet (strands 1, 5, 6, 9, and 10) establishes a stable but flexible connection to the NTD, the second β-sheet (strands 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 11) provides a scaffold against which the helices K, L, M, O, and Q are stacked (Fig. 1B and C). A DALI search identified the photosystem II protease D1P (root mean square deviation [RMSD], 2.0 Å for 178 Cα atoms) (20), the signaling peptidase CtpB from B. subtilis (RMSD, 2.7 Å for 200 Cα atoms) (21), the chlamydial protease CPAF (RMSD, 2.7 Å for 199 Cα atoms) (22), and two hypothetical bacterial peptidases from Bacteroides uniformis (PDB code 4GHN; RMSD, 2.4 Å for 182 Cα atoms) and Parabacteroides merdae (PDB code 4L8K; RMSD, 2.8 Å for 194 Cα atoms) as harboring domains with structural homology to the CTD. A superimposition showed that the core of the CTD is well conserved within this group of proteins, whereas helices N, O, and P appear to be unique to CT441 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Residues 528 to 644 (including helices N, O, P, and Q), previously annotated as DUF3340 (domain of unknown function), are part of the CTD (Fig. 1B). This region is of critical importance for substrate processing, since a truncated CT441 variant (CT441ΔDUF3340) is unable to cleave a fluorogenic reporter peptide (Fig. 1E).

The active-site residues S455 and K481 are located in the deep crevice between the NTD and the CTD (Fig. 1B). Although the proteolytically inactive S455A variant (CT441°) was used for crystallization, side chain positions indicate that K481-Nζ can accept a proton from S455-Oγ and thus acts as a general base during catalysis (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, in CT441, a hydrogen bond between the side chains of K481 and Q485 secures an optimal positioning of the general base (Fig. 1D). This suggests that Q485 has a function similar to that of the aspartate residue in the catalytic triad of classical serine proteases. Indeed, the replacement of either S455, K481, or Q485 by alanine prohibits proteolytic activity, corroborating that CT441 utilizes a catalytic triad for substrate cleavage (Fig. 1E). The active-site cleft of CT441 is rather shallow. With the exception of a deep, mainly hydrophobic S1 pocket, it contains surfaces rather than pronounced depressions to accommodate amino acid side chains of substrate molecules (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). It cannot be excluded that the PDZ domain, not visible in our structure, participates in the binding of substrate molecules and therefore might influence the cleavage specificity of CT441. PDZ domains usually rely on a conserved GLGF motif for the recognition of substrates (23). To investigate if the corresponding motif 253GIGV256 in CT441 plays a similar role, we replaced the isoleucine with tryptophan, thereby limiting the access to the peptide-binding groove of the PDZ domain. Indeed, the resulting CT441I254W variant was unable to cleave the reporter peptide (Fig. 1E), demonstrating that substrate recognition by the PDZ domain is of critical importance for the proteolytic activity of CT441.

Results from size exclusion chromatography indicate that CT441 is monomeric in solution. However, in the crystal, CT441 forms homodimers via a symmetric, mostly hydrophilic interface region located in the CTD with a large buried surface area of ∼1,300 Å2 per molecule (Fig. 2A and B), which is typical for stable protein-protein interactions (24). The interface, which includes numerous hydrogen bonds, consists of helices O, Q, and loop β2-3 of one molecule and corresponding regions of a second molecule (Fig. 2B). Since identical dimers were also observed in a second crystal form of CT441 (space group C2221), it cannot be excluded that this assembly has physiological relevance.

FIG 2.

Homodimer formation of CT441. (A) CT441 homodimer colored as in Fig. 1B, with the second protomer in a lighter shade. The dashed line indicates the 2-fold symmetry of the homodimer. (B) Homodimerization interface within the CTD. Structural elements of one CT441 molecule (helices αO, αQ, and loop β2-3; purple) interact with corresponding elements of an adjacent molecule (helices αO′, αQ′, and loop β2-3′; green) to form a symmetric interface.

CT441 is able to degrade SRAP1 in vitro.

It has been proposed that after the infection of human host cells with C. trachomatis, CT441 interacts with SRAP1 to modulate the estrogen signaling pathway (9). To analyze this interaction in vitro, SRAP1 was recombinantly produced in E. coli, purified, and incubated with lysates of C. trachomatis-infected HEK293 cells. Western blot analysis revealed that lysates collected 24 to 48 h postinfection (p.i.) effectively degraded recombinant SRAP1 (Fig. 3A). Lysates from uninfected cells or cells collected 8 h p.i. did not show any proteolytic activity toward SRAP1. It is conceivable that the unspecific chlamydial protease CPAF cleaves SRAP1 under these conditions. Indeed, assays performed with a CPAF-deficient C. trachomatis strain (25) confirmed this notion (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

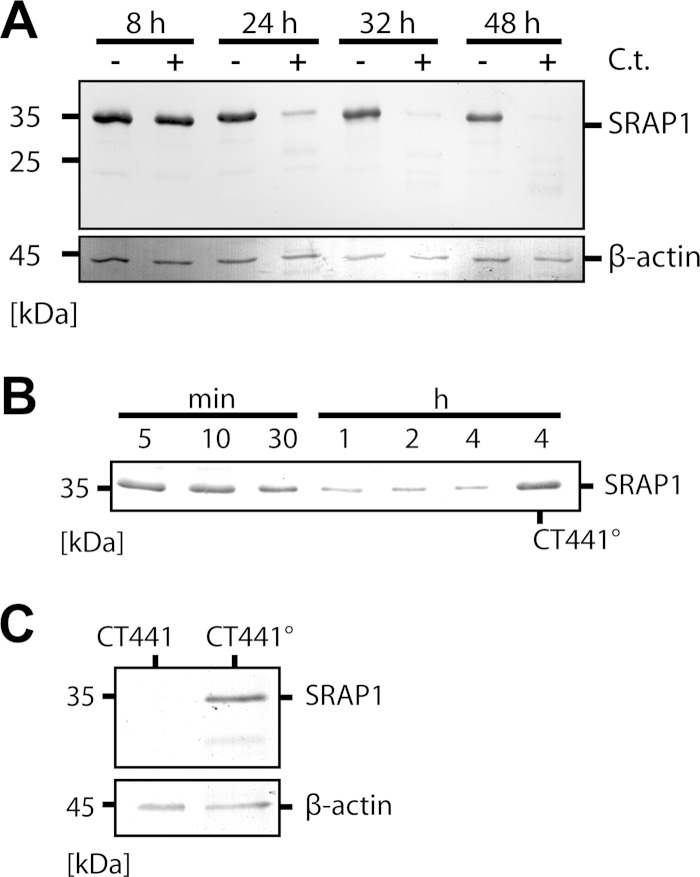

FIG 3.

CT441 is able to degrade SRAP1. (A) HEK293 cells were lysed at indicated time points after infection with C. trachomatis (C.t.). Lysates collected 24 h p.i. or later show pronounced proteolytic activity against purified SRAP1 recombinantly produced in E. coli. In contrast, lysates of uninfected HEK293 cells show no proteolytic activity. (B) CT441 was incubated with SRAP1 produced in E. coli for indicated periods of time. (C) CT441 was incubated with SRAP1 produced in HEK293 cells. In both cases, CT441 was able to degrade SRAP1, whereas proteolytically incompetent CT441° shows no SRAP1 cleavage. All samples were analyzed by Western blotting using a commercial anti-SRAP1 antibody; a commercial anti-β-actin antibody was used for detection of β-actin as a loading control.

To specifically analyze the interaction between CT441 and SRAP1, both proteins were purified and coincubated in vitro. Interestingly, CT441 efficiently hydrolyzed SRAP1 with almost complete substrate turnover within 1 h, whereas CT441° did not show any proteolytic activity even after 4 h of incubation time (Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained using SRAP1 produced in HEK293 cells (Fig. 3C). Lowering the reaction temperature to 4°C allowed us to isolate distinct SRAP1 degradation intermediates, which were subsequently subjected to N-terminal amino acid sequencing and identification of two primary cleavage sites between Ala14-Glu15 and Tyr35-Gly36 (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Several weaker degradation bands of lower molecular mass (<25 kDa) could not be successfully sequenced. Based on these results, we propose that CT441 initiates the degradation of SRAP1 by cleaving two peptide bonds in the N-terminal region of SRAP1, which then leads to a rapid processing of SRAP1 into small fragments.

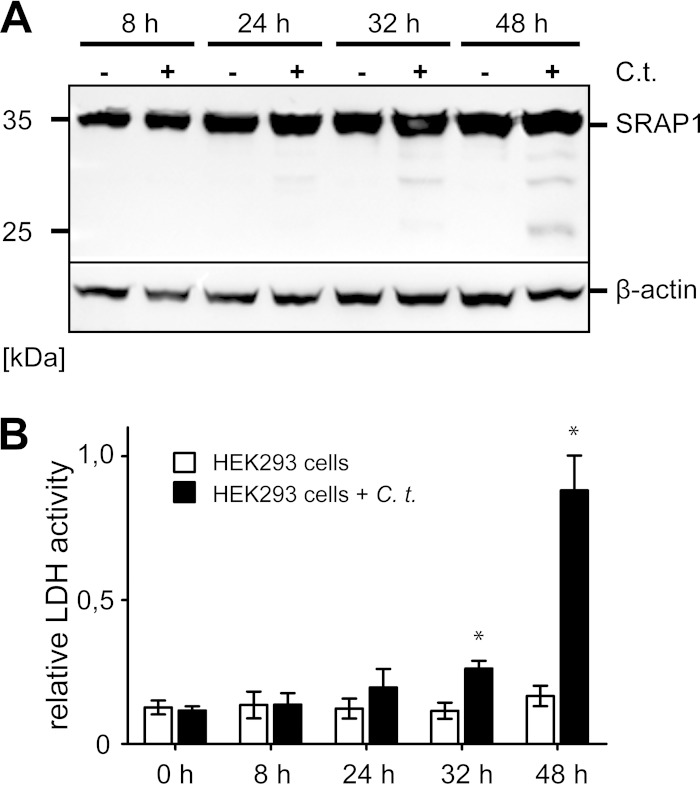

Host cells infected with C. trachomatis do not show significantly reduced SRAP1 levels.

Our experiments clearly show that CT441 and CPAF both have the capacity to cleave SRAP1 in vitro. To address the question of whether CT441 or other chlamydial proteases interfere with cytoplasmic SRAP1 levels during intracellular chlamydial development, lysates of C. trachomatis-infected host cells were analyzed. To overcome low inherent SRAP1 levels, SRAP1-overexpressing HEK293 cells (HEK293SRAP1+) were generated. HEK293SRAP1+ cells infected with C. trachomatis were harvested and lysed in the presence of a strongly denaturing buffer containing 8 M urea. Under these conditions, no significant SRAP1 degradation was observed up to 24 h p.i. (Fig. 4A). Even at late stages of the infection (32 h and 48 h p.i.), the bulk of the cytosolic SRAP1 appeared to be intact, with only minor degradation bands detectable by Western blotting (Fig. 4A). Host cell viability was analyzed by monitoring lactate dehydrogenase activity in the cell culture medium. C. trachomatis-induced disruption of the host cell plasma membrane was detected 32 h p.i., and more than 90% of the host cells were lysed 48 h p.i. (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the first appearance of SRAP1 degradation bands (Fig. 4A) coincided with the disruption of the plasma membrane (Fig. 4B) and release of infectious chlamydial elementary bodies from the host cell (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material).

FIG 4.

SRAP1 degradation in host cells is detectable only at late stages of the infection. (A) HEK293 cells overexpressing cytosolic SRAP1 were lysed at indicated time points after infection with C. trachomatis (C.t.). To prevent ongoing proteolysis during lysate preparation, cells were harvested in the presence of a strongly denaturing buffer containing 8 M urea. Although lysates collected 32 h p.i. or later show some proteolytic activity, the bulk of SRAP1 remains unaffected. Lysates of uninfected HEK293 cells show no proteolytic activity against SRAP1. A commercial anti-β-actin antibody was used for detection of β-actin as a loading control. (B) Supernatants of HEK293 cells were analyzed for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity at indicated time points p.i. with C. trachomatis. A statistically significant increase of LDH release due to disruption of host cells by C. trachomatis was observed at 32 h and 48 h p.i. (indicated by asterisks).

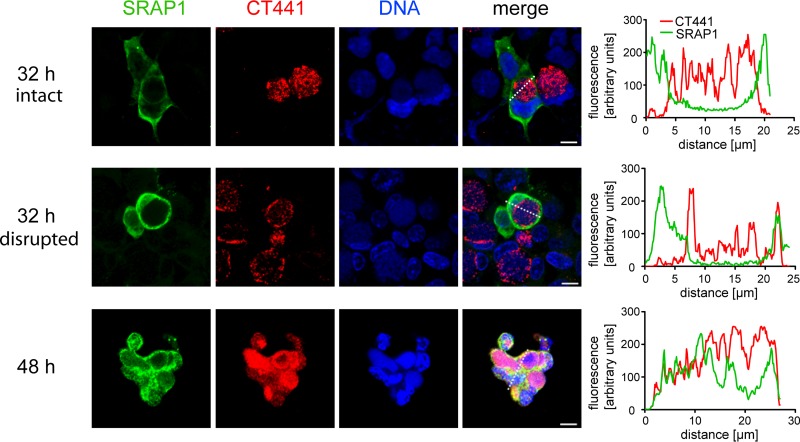

CT441 and SRAP1 colocalize only after disruption of the inclusion membrane.

To investigate whether CT441-mediated degradation of SRAP1 occurs in intact C. trachomatis-infected cells or as a consequence of cellular disruption at later stages of the infection, we analyzed SRAP1 and CT441 expression in C. trachomatis-infected HEK293SRAP1+ cells by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Within the first 32 h p.i., SRAP1 was detected mainly in the cytosol of the transfected host cells, whereas CT441 staining was restricted to the chlamydial inclusion (Fig. 5, upper panel). Quantification of the fluorescence signal across the interface between the cytosol and the inclusion revealed no overlap between the signals for CT441 and SRAP1 in intact cells. However, in some cells, a partial overlap of the fluorescence signals for CT441 and SRAP1 in the vicinity of the inclusion was observed 32 p.i. (Fig. 5, middle panel). Since these cells are rounded, it is likely that they belong to the population of dying cells with partially disrupted cellular membranes observed 32 h p.i. (Fig. 4B). Immunofluorescence images taken 48 h p.i. showed an almost complete overlap of signals for CT441 and SRAP1 in cells with abrogated cellular compartmentalization and completely disrupted chlamydial inclusions (Fig. 5, lower panel). These results indicate that CT441 and SRAP1 colocalize only at very late stages of the infection.

FIG 5.

CT441 colocalizes with SRAP1 only after disruption of the chlamydial inclusion. Infected HEK293 cells overexpressing SRAP1 were stained with antibodies against SRAP1 (green) and CT441 (red), DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). Representative confocal images 32 h or 48 h p.i. are shown (bar = 5 μm). The right column displays fluorescence distribution profiles along broken lines in the merged confocal images. Most cells imaged 32 h p.i. do not show overlapping profiles of SRAP1 and CT441 (upper panel). However, in some cells, overlapping fluorescence profiles were observed as early as 32 h p.i. (middle panel), and in most cells, this was the case at 48 h p.i. (lower panel). This indicates a progressing colocalization of SRAP1 and CT441 at late stages of the infection, most likely due to the disruption of the inclusion membrane before egress of C. trachomatis from the host cell.

CT441 is a bifunctional enzyme with chaperone and protease activities.

In contrast to findings for eukaryotes, PDZ-containing proteins are relatively scarce in prokaryotes (26). Whereas eukaryotic PDZ domains mostly serve as protein-protein interaction modules, their prokaryotic counterparts are often involved in substrate binding or regulatory processes (23). The role of PDZ domains is well understood in bacterial HtrA (high temperature requirement A) proteases, which are prominent protein quality control factors in the bacterial periplasm (27, 28). Interestingly, several HtrA proteins are bifunctional enzymes with tightly regulated protease and chaperone activities, facilitating degradation or refolding of misfolded periplasmatic proteins. Since CT441 homologues such as E. coli Tsp are also involved in protein quality control processes (8), we tested if CT441 possesses a chaperone-like activity as reported for the HtrA proteins DegP and DegQ (28). Using a chaperone assay based on the heat-induced denaturation of citrate synthase, we found that CT441 has a pronounced protective effect (Fig. 6). Comparable results were obtained for the inactive variant CT441° and for CT441°ΔDUF3340, indicating independent chaperone and protease functions. In contrast, a truncation of the protease domain (CT441NTD&PDZ, comprising residues 22 to 341) or of the protease along with the PDZ domain (CT441NTD, comprising residues 22 to 242) resulted in reduced chaperone activity. Taken together, these results indicate that CT441 exhibits pronounced chaperone activity that depends on the presence of all three domains.

DISCUSSION

To survive in the hostile environment inside the host cell, C. trachomatis has developed sophisticated molecular mechanisms, including the remodeling of intracellular vacuoles and modulation of the host cell immune response. CT441 has been reported to act as a chlamydial effector protein that interacts with SRAP1 and partially alleviates estrogen signaling pathways (9). In contrast to previous results, we show that CT441 is able to cleave SRAP1. These conflicting findings are most likely due to differences in the protein variants (N-terminal (HA)2 tag in CT441, different isoform of SRAP1) and the experimental setup (coexpression of CT441 and SRAP1 in the cytoplasm of HEK293 cells) used by Borth et al. (9). However, most importantly our results show no significant SRAP1 degradation during the intracellular developmental cycle of C. trachomatis. Furthermore, immunofluorescence images did not provide any evidence for the colocalization of CT441 and SRAP1 prior to the disruption of the inclusion membrane at the end of the infection cycle (Fig. 4A and 5). This is in line with findings from others who also could not detect CT441 outside the chlamydial inclusion (29, 30). Given the detection limits of immunofluorescence imaging, a direct interaction of CT441 with SRAP1 cannot be completely ruled out. Our data, however, strongly indicate that CT441 does not result in extensive SRAP1 degradation in intact cells with maintained inclusion morphology. Colocalization of CT441 and SRAP1 could be detected only at very late stages of the infection, when the inclusion membrane starts to disrupt and infectious chlamydiae are released from the host cell (31–33). The liberation of CT441 might therefore play a role, e.g., by degrading SRAP1 or interacting with other chlamydial or host cell proteins in the extracellular phase of the chlamydial developmental cycle.

To provide a framework for a detailed analysis of its molecular function, we have determined the three-dimensional structure of CT441. The NTD of CT441 displays a novel fold, with no structural homologues present in the PDB. According to sequence analysis and secondary structure prediction (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material), many Tsp proteins include an NTD structurally very similar to that of CT441. In CT441, the NTD is crucial for folding and/or solubility, since CT441 variants lacking the NTD tend to aggregate and could not be purified. In addition, the NTD is important for chaperone activity of CT441 (see below). In contrast to the NTD, the core region of the CTD is structurally well conserved among Tsp homologues from prokaryotes (3DOR, 4L8K, 4GHN, and 4C2E) (21, 22) and eukaryotes (1FC6) (20). The CTD of CT441 mediates the formation of homodimers and harbors the active-site residues. It is easily possible that dimerization is needed for proteolytic activity and that the disruption of the dimerization interface in CT441ΔDUF3340 is responsible for its inability to cleave peptide substrates (Fig. 1E). However, the exact role of dimer formation in CT441 has to be addressed in future experiments. Our combined structural and mutational analysis revealed that CT441 harbors a catalytic triad composed of S455, K481, and Q485. A comparison of CT441 active-site residues with homologous structures of CPAF (22), D1P (20), and CtpB (21) revealed an equivalent positioning of the nucleophile (for CT441, S455; for CPAF, S499; for D1P, S372; for CtpB, S309) and the general base (for CT441, K481; for CPAF, H105; for D1P, K397; for CtpB, K334) (see Fig. S8A). Whereas in CT441, Q485 is crucial for the correct positioning of the general base (Fig. 1D and E), a water-mediated hydrogen bond to E558 fulfills this function in CPAF. Interestingly, Q401 of D1P corresponds to Q485 of CT441. Although in the D1P structure, which displays an inactive state of the enzyme, Q401 is not in a position to contact the general base (distance from K397-Nζ to Q401-Oε1, 6.5 Å) (20), it is likely that a hydrogen bond between the two residues is formed in the active conformation of the enzyme. Indeed, it has been proposed that many Ser/Lys proteases use a third residue for the positioning of the catalytic lysine (34). Q485 is essential for proteolytic activity of CT441 and is highly conserved among related proteins from many bacteria, higher plants, and algae (35, 36) (see Fig. S8B). It is therefore easily possible that in many if not all Tsps and related proteases, a Gln residue complements the prototypical Ser/Lys dyad to form a catalytic triad, as observed in CT441. Very recently, a Ser/Lys/Gln catalytic triad has also been identified in CtpB from Bacillus subtilis (21). Due to high flexibility of loop regions connecting the PDZ domain to the NTD and CTD, the PDZ domain of CT441 is not defined in the crystal structure. Highly flexible interdomain loops have also been observed for D1P (20), and a repositioning of the PDZ domain is important for transforming CtpB into its active state (21). It is therefore likely that for substrate binding and/or catalysis, a repositioning of the PDZ domain is important for Tsp proteins in general. PDZ domains typically bind the C terminus of substrate molecules (23); however, in some cases internal peptides are recognized (37). Our mutational analysis revealed that in CT441, the integrity of the conserved substrate recognition motif within the PDZ domain is critical for proteolytic activity (Fig. 1E). Therefore, several modes of action for the PDZ domain during catalysis are conceivable: (i) the PDZ domain recognizes internal residues of the substrate close to the cleavage site and modulates binding specificity of CT441; (ii) an interaction of the PDZ domain with the substrate has regulatory functions, e.g., by allosterically controlling processing of substrates, as reported for HtrA family proteases (28) and CtpB (21); or (iii) the PDZ domain secures a substrate protein to allow for efficient processing, e.g., by using a hold-and-bite mechanism (38). For shorter substrates, such as our reporter peptide, allosteric regulation or a hold-and-bite mechanism is unlikely, because the rather bulky C-terminal AMC residue of the peptide should prevent recognition by the PDZ in the first place. However, it cannot be excluded that such mechanisms are relevant for the processing of larger protein substrates. CT441 can process SRAP1 in vitro and has been reported to specifically interact with SRAP1 via its PDZ domain (9). It is interesting to note that SRAP1 contains a sequence in the C-terminal region with similarity to the SsrA degradation tag, a molecular label that is found on dysfunctional cytoplasmatic and periplasmatic proteins in prokaryotes (SsrA, AANDENYALAA; SsrA-like sequence in SRAP1, 213AANEEKSAATA223). The SsrA tag is recognized by the PDZ domain of E. coli Tsp and other proteases of the protein quality control system to facilitate efficient degradation of the labeled protein substrate (39).

Our results on structure, function, and intracellular localization of CT441 are compatible with a role in chlamydial protein quality control. Interestingly, other prokaryotic PDZ proteins have also been implicated to counteract protein folding stress, with the HtrA family members DegP and DegQ representing prominent examples. Our analysis revealed that apart from its proteolytic function, CT441 can also act as a chaperone. This novel activity is independent of a functional protease active site. Although the isolated NTD shows some protective effect against heat-induced denaturation of substrates, the presence of the PDZ and protease domains is needed for full chaperone activity. In contrast to the well-characterized proteolytic function of HtrA proteins, the chaperone function is still not well understood. Results from cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) studies of DegQ from E. coli showed that the chaperone function is most likely dependent on the formation of large, higher-order protein complexes consisting of at least 12 DegQ molecules (40). However, the chaperone activity of DegQ from Legionella fallonii seems to be independent of the assembly of large complexes (41). For CT441, oligomerization is not necessary, since a protein variant lacking the C-terminal DUF3340 domain, including the dimerization interface, exhibits full chaperone activity (Fig. 6). Since CT441 shares an identical domain organization and significant sequence similarity with Tsp proteins from other organisms, the chaperone activity might also be a common feature of these proteins.

The establishment of genetic modification tools has dramatically advanced the field of Chlamydia research in the last 3 years (42, 43). Having these new techniques at hand, it is now possible to directly target chlamydial factors of interest for the detailed analysis of host-pathogen interactions. With information on molecular structure and catalytic function available, CT441 will be a very exciting target for future research into chlamydial pathogenicity mechanisms and protein quality control.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was funded by the DFG through HA 6969/2-1 and the Cluster of Excellence, Inflammation at Interfaces (EXC 306).

We thank B. Schwarzloh, S. Schmidtke, S. Zoske, A. Hellberg, and S. Pätzmann for expert technical assistance. We are grateful to G. Zhong, San Antonio, TX, for providing the CT441 antibody, to F. Hänel, Jena, Germany, for providing the SRAP1 expression plasmid, and to R. Valdivia, Durham, NC, for providing the CPAF-deficient C. trachomatis strain. We acknowledge access to beamline BL14.2 at BESSY II (Berlin, Germany) via the Joint Berlin MX-Laboratory, beamline ID29 at ESRF (Grenoble, France), beamline P11 at PETRAIII (Hamburg, Germany), and beamline PX I und PX III at SLS (Villigen, Switzerland).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.02140-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC. 2013. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2012. CDC, Atlanta, GA: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats12/surv2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peipert JF. 2003. Clinical practice. Genital chlamydial infections. N Engl J Med 349:2424–2430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp030542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conrad TA, Yang Z, Ojcius D, Zhong G. 2013. A path forward for the chlamydial virulence factor CPAF. Microbes Infect 15:1026–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen AL, Johnson KA, Lee JK, Sutterlin C, Tan M. 2012. CPAF: a chlamydial protease in search of an authentic substrate. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002842. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lad SP, Li J, da Silva Correia J, Pan Q, Gadwal S, Ulevitch RJ, Li E. 2007. Cleavage of p65/RelA of the NF-κB pathway by Chlamydia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:2933–2938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608393104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lad SP, Yang G, Scott DA, Wang G, Nair P, Mathison J, Reddy VS, Li E. 2007. Chlamydial CT441 is a PDZ domain-containing tail-specific protease that interferes with the NF-κB pathway of immune response. J Bacteriol 189:6619–6625. doi: 10.1128/JB.00429-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christian J, Vier J, Paschen SA, Häcker G. 2010. Cleavage of the NF-κB family protein p65/RelA by the chlamydial protease-like activity factor (CPAF) impairs proinflammatory signaling in cells infected with chlamydiae. J Biol Chem 285:41320–41327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.152280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keiler KC, Waller PR, Sauer RT. 1996. Role of a peptide tagging system in degradation of proteins synthesized from damaged messenger RNA. Science 271:990–993. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borth N, Massier J, Franke C, Sachse K, Saluz HP, Hänel F. 2010. Chlamydial protease CT441 interacts with SRAP1 co-activator of estrogen receptor α and partially alleviates its co-activation activity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 119:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leslie AGW, Powell HR. 2007. Processing diffraction data with MOSFLM, p 41–51. In Read RJ, Sussman JL (ed), Evolving methods for macromolecular crystallography. NATO science series, vol 245 Springer, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6316-9_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kabsch W. 2010. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans P. 2006. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terwilliger TC, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Afonine PV, Moriarty NW, Zwart PH, Hung LW, Read RJ, Adams PD. 2008. Iterative model building, structure refinement and density modification with the PHENIX AutoBuild wizard. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 64:61–69. doi: 10.1107/S090744490705024X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowtan K. 2006. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62:1002–1011. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906022116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, Adams PD. 2012. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buchner J, Grallert H, Jakob U. 1998. Analysis of chaperone function using citrate synthase as nonnative substrate protein. Methods Enzymol 290:323–338. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(98)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holm L, Rosenström P. 2010. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res 38:W545–W549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liao DI, Qian J, Chisholm DA, Jordan DB, Diner BA. 2000. Crystal structures of the photosystem II D1 C-terminal processing protease. Nat Struct Biol 7:749–753. doi: 10.1038/78973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mastny M, Heuck A, Kurzbauer R, Heiduk A, Boisguerin P, Volkmer R, Ehrmann M, Rodrigues CD, Rudner DZ, Clausen T. 2013. CtpB assembles a gated protease tunnel regulating cell-cell signaling during spore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 155:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Z, Feng Y, Chen D, Wu X, Huang S, Wang X, Xiao X, Li W, Huang N, Gu L, Zhong G, Chai J. 2008. Structural basis for activation and inhibition of the secreted Chlamydia protease CPAF. Cell Host Microbe 4:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye F, Zhang M. 2013. Structures and target recognition modes of PDZ domains: recurring themes and emerging pictures. Biochem J 455:1–14. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krissinel E, Henrick K. 2007. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol 372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snavely EA, Kokes M, Dunn JD, Saka HA, Nguyen BD, Bastidas RJ, McCafferty DG, Valdivia RH. 2014. Reassessing the role of the secreted protease CPAF in Chlamydia trachomatis infection through genetic approaches. Pathog Dis 71:336–351. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jelen F, Oleksy A, Smietana K, Otlewski J. 2003. PDZ domains—common players in the cell signaling. Acta Biochim Pol 50:985–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clausen T, Kaiser M, Huber R, Ehrmann M. 2011. HTRA proteases: regulated proteolysis in protein quality control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12:152–162. doi: 10.1038/nrm3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen G, Hilgenfeld R. 2013. Architecture and regulation of HtrA-family proteins involved in protein quality control and stress response. Cell Mol Life Sci 70:761–775. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1076-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw AC, Vandahl BB, Larsen MR, Roepstorff P, Gevaert K, Vandekerckhove J, Christiansen G, Birkelund S. 2002. Characterization of a secreted Chlamydia protease. Cell Microbiol 4:411–424. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhong G. 2011. Chlamydia trachomatis secretion of proteases for manipulating host signaling pathways. Front Microbiol 2:14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bastidas RJ, Elwell CA, Engel JN, Valdivia RH. 2013. Chlamydial intracellular survival strategies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 3:a010256. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beatty WL. 2007. Lysosome repair enables host cell survival and bacterial persistence following Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Cell Microbiol 9:2141–2152. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lutter EI, Barger AC, Nair V, Hackstadt T. 2013. Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane protein CT228 recruits elements of the myosin phosphatase pathway to regulate release mechanisms. Cell Rep 3:1921–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paetzel M, Karla A, Strynadka NC, Dalbey RE. 2002. Signal peptidases. Chem Rev 102:4549–4580. doi: 10.1021/cr010166y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoge R, Laschinski M, Jaeger KE, Wilhelm S, Rosenau F. 2011. The subcellular localization of a C-terminal processing protease in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Lett 316:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inagaki N, Maitra R, Satoh K, Pakrasi HB. 2001. Amino acid residues that are critical for in vivo catalytic activity of CtpA, the carboxyl-terminal processing protease for the D1 protein of photosystem II. J Biol Chem 276:30099–30105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hillier BJ, Christopherson KS, Prehoda KE, Bredt DS, Lim WA. 1999. Unexpected modes of PDZ domain scaffolding revealed by structure of nNOS-syntrophin complex. Science 284:812–815. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krojer T, Pangerl K, Kurt J, Sawa J, Stingl C, Mechtler K, Huber R, Ehrmann M, Clausen T. 2008. Interplay of PDZ and protease domain of DegP ensures efficient elimination of misfolded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:7702–7707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803392105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spiers A, Lamb HK, Cocklin S, Wheeler KA, Budworth J, Dodds AL, Pallen MJ, Maskell DJ, Charles IG, Hawkins AR. 2002. PDZ domains facilitate binding of high temperature requirement protease A (HtrA) and tail-specific protease (Tsp) to heterologous substrates through recognition of the small stable RNA A (ssrA)-encoded peptide. J Biol Chem 277:39443–39449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malet H, Canellas F, Sawa J, Yan J, Thalassinos K, Ehrmann M, Clausen T, Saibil HR. 2012. Newly folded substrates inside the molecular cage of the HtrA chaperone DegQ. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:152–157. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wrase R, Scott H, Hilgenfeld R, Hansen G. 2011. The Legionella HtrA homologue DegQ is a self-compartmentizing protease that forms large 12-meric assemblies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:10490–10495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101084108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kari L, Goheen MM, Randall LB, Taylor LD, Carlson JH, Whitmire WM, Virok D, Rajaram K, Endresz V, McClarty G, Nelson DE, Caldwell HD. 2011. Generation of targeted Chlamydia trachomatis null mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:7189–7193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102229108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Kahane S, Cutcliffe LT, Skilton RJ, Lambden PR, Clarke IN. 2011. Development of a transformation system for Chlamydia trachomatis: restoration of glycogen biosynthesis by acquisition of a plasmid shuttle vector. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.