Abstract

Expression of ace (adhesin to collagen of Enterococcus faecalis), encoding a virulence factor in endocarditis and urinary tract infection models, has been shown to increase under certain conditions, such as in the presence of serum, bile salts, urine, and collagen and at 46°C. However, the mechanism of ace/Ace regulation under different conditions is still unknown. In this study, we identified a two-component regulatory system GrvRS as the main regulator of ace expression under these stress conditions. Using Northern hybridization and β-galactosidase assays of an ace promoter-lacZ fusion, we found transcription of ace to be virtually absent in a grvR deletion mutant under the conditions that increase ace expression in wild-type OG1RF and in the complemented strain. Moreover, a grvR mutant revealed decreased collagen binding and biofilm formation as well as attenuation in a murine urinary tract infection model. Here we show that GrvR plays a major role in control of ace expression and E. faecalis virulence.

INTRODUCTION

Enterococcus faecalis is a Gram-positive commensal bacterium of the gastrointestinal tract and also a common cause of hospital-acquired infections and endocarditis (1). During experimental infections, the adhesin to collagen of E. faecalis (Ace) plays an important role which has been attributed to mediating binding of E. faecalis to human extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as collagen (types I and IV), laminin, and dentin (2–4). Different infection models have shown attenuation of ace deletion mutants (5–7) and specific anti-recombinant Ace (rAce) antibodies were shown to confer protection against E. faecalis infection in an experimental endocarditis model (6). Therefore, Ace is considered a virulence factor in E. faecalis infection.

In order to better understand the role of Ace, it is important to study the regulation mechanisms of ace expression and surface display. Previous works have identified several environmental factors regulating ace expression; e.g., transcription of ace was increased when E. faecalis was grown at 46°C and grown in the presence of 40% horse serum, urine, and bile salts (5, 8, 9). In addition, levels of Ace on the cell surface are dependent on the E. faecalis strain and growth phase (10–12). With E. faecalis OG1RF, Ace is increased in the early exponential phase but reduced in the stationary phase; however, with E. faecalis JH2-2, it is maintained in later growth phases (10–12). The decrease in stationary-phase Ace in strain OG1RF was shown to be dependent on a functional fsr quorum-sensing system controlling the expression of gelatinase (GelE), which cleaves Ace from the OG1RF cell surface in late-phase cultures (11). Strains such as JH2-2 (lacking a complete fsr system operon) as well as fsr and gelE mutants of OG1RF do not cleave Ace from the surface (11), since they do not produce gelatinase. In other words, the amount of Ace on OG1RF strains is regulated in part at the posttranslational level. At the transcriptional level, the enterococcal regulator of survival (Ers) was previously reported as a repressor of ace expression in E. faecalis JH2-2 (5). In E. faecalis OG1RF, this regulator does not seem to play a role, as deletion of ers did not affect ace expression under the various tested conditions (13). Deletion of ccpA encoding the transcriptional regulator CcpA (catabolite control protein A) from OG1RF resulted in significantly decreased levels of Ace surface expression in the early growth phase and an impaired ability to adhere to collagen in comparison to the wild-type (12). However, transcriptional levels of ace were similar in both OG1RF and the ccpA mutant, indicating that CcpA is not directly involved in regulating ace transcription.

Therefore, a transcriptional regulator that controls ace expression in OG1RF under various environmental conditions has not yet been identified. In this study, we identified the two-component regulatory system (TCS) GrvRS (global regulator of virulence; formerly EtaRS [14]) as a positive regulator of ace transcription in E. faecalis OG1RF under various environmental conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. E. faecalis and Escherichia coli were grown normally in brain heart infusion (BHI) and Luria Bertani (LB) media at 37°C, respectively. E. faecalis strains were also grown in BHI supplemented with 40% horse serum (BHIS) and in BHI with bile salts (0.02 and 0.04%) at 37°C as well as in BHI at 46°C (13). For the biofilm assay, E. faecalis was grown in tryptic soy broth supplemented with 0.25% glucose (TSBG) (15). Bile esculin azide (BEA) agar was used to quantitate enterococcal CFU from mouse tissue. Growth curves were determined as follows: E. faecalis strains were grown overnight and reinoculated (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.05) into BHI or BHIS and the OD600 was measured every hour until stationary phase. Antibiotics used for E. faecalis were erythromycin (10 μg/ml), fusidic acid (25 μg/ml), rifampin (100 μg/ml), and gentamicin (150 μg/ml); for E. coli, erythromycin (250 μg/ml), gentamicin (25 μg/ml), and kanamycin (50 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis strains | ||

| CK111 | OG1Sp upp4::P23 repA4; provides RepA for replication of pHOU1 | 17 |

| OG1RF | Fusr Rifr | 41 |

| TX10275 | TCS disruption mutant; OG1RF_12536::pBluescript SK(−) with aph(3′)-IIIa Kmr | 14 |

| TX10276 | TCS disruption mutant; OG1RF_11414::pBluescript SK(−) with aph(3′)-IIIa Kmr | 14 |

| TX10292 | TCS disruption mutant; OG1RF_11029::pBluescript SK(−) with aph(3′)-IIIa Kmr | 14 |

| TX37200 | TCS disruption mutant; OG1RF_10259::pBluescript SK(−) with aph(3′)-IIIa Kmr | 14 |

| TX10293 | TCS disruption mutant; grvR::pBluescript SK(−) with aph(3′)-IIIa Kmr | 14 |

| TX5733 | ΔgrvR; nonpolar in-frame deletion of grvR from OG1RF | This study |

| TX5735 | grvR*; reconstituted grvR of TX5733 with a silent nucleotide change for differentiation from OG1RF | This study |

| TX5652 | Δace; nonpolar in-frame deletion of ace from OG1RF | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| EC1000 | E. coli host strain; provides RepA; Kmr | 42 |

| DH5α | E. coli host strain used for routine cloning | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHOU1 | Plasmid for mutagenesis; Gmr | 16 |

| pCR-TOPO | Plasmid for PCR cloning; Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pTEX6075b | ace promoter::lacZ fusion in pKAF7; Emr | 13 |

| pTX5735a | pCR-TOPO containing grvR for complementation | This study |

| pTX5735b | pTX5735a containing a point mutation in Leu-109 codon of grvR | This study |

| pTX5735c | pHOU1 containing grvR* from pTX5735b | This study |

| pTX5733 | pHOU1 containing ΔgrvR construct | This study |

Em, erythromycin; Fus, fusidic acid; Gm, gentamicin; Km, kanamycin; Rif, rifampin.

Construction of deletion mutants and complementation.

A grvR nonpolar in-frame deletion mutant was created using the pHOU1 plasmid (16). DNA fragments upstream (664 bp) and downstream (795 bp) of the grvR gene were amplified with primer pairs UpF-BamHI plus UpR and DownF plus DownR-SphI, respectively. The open reading frame (ORF) of grvR is 687 bp, and the deletion was designed so that the internal 621 bp of the gene were in-frame deleted, leaving 6 bp of the N end (including the start codon) and 60 bp of the C end (including the termination codon) of grvR in the ΔgrvR strain. Primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Amplified fragments were joined by overlapping PCR, digested with BamHI and SphI, and then ligated into pHOU1 digested with the same restriction enzymes. The construct, designated pTEX5733, was electroporated into E. faecalis CK111 (17), which was then conjugated with E. faecalis OG1RF. The first recombination event was selected on BHI agar containing fusidic acid, gentamicin, and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) (200 μg/ml). Blue colonies showing fusidic acid and gentamicin resistance were further characterized to verify recombination into the grvR region using outside primer pairs of outsideF plus DownR-SphI and UpF-BamHI plus outsideR. The second recombination event was obtained by spreading the first recombinants on MM9YEG supplemented with 10 mM p-Cl-Phe as described previously (16). For complementation (reconstitution) of ΔgrvR, the grvR region was amplified with the primers UpF-BamHI plus DownR-SphI and then subcloned into pCR-TOPO plasmid (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). A silent mutation (CTA) was introduced into the leucine codon TTA corresponding to amino acid position 109 using the primers pmF and pmR (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), resulting in grvR*. Leucine is the most frequent amino acid (28 out of 228 amino acids) in GrvR. Among 28 leucine codons, codon usage was as follows: 16 TTA, 5 CTT, 4 TTG, and 3 CTA. Therefore, the complemented strain contains the same Leu-109 but with a silent nucleotide mutation to distinguish the complemented strain from wild-type OG1RF. Deletion (TX5733 [ΔgrvR]) and complemented (TX5735 [grvR*]) strains were confirmed by DNA sequencing and by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns. The ace nonpolar markerless deletion mutant of OG1RF with a deletion from the ace start codon to the termination codon was also constructed with pHOU1 plasmid using the primer pairs AceA plus AceB (to amplify the upstream fragment) and AceC plus AceD (to amplify downstream fragment).

β-Galactosidase activity assay.

Five previously described OG1RF TCS mutants (14) were electroporated with pTEX6075b containing an aceOG1RF promoter-lacZ fusion (13) and selected on BHI plates containing X-Gal and erythromycin. For β-galactosidase assays, overnight cultures of E. faecalis were reinoculated to an initial OD600 of 0.05 into prewarmed BHI or BHIS containing erythromycin. At mid-exponential phase (OD600 = 0.5 ± 0.05), 1 ml of samples was centrifuged, suspended in 1 ml Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol [pH 7.0]), and disrupted using a mini-BeadBeater (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK). After centrifugation, supernatants were used for the β-galactosidase activity as described previously (18).

RNA isolation and Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA isolation and Northern hybridizations were performed as described previously (13). An overnight culture was reinoculated into 20 ml BHI broth or BHIS to a starting OD600 of 0.05. At the mid-exponential phase (OD600 = 0.5 ± 0.5), 5 ml of the culture was mixed with 10 ml RNAprotect reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and collected for RNA isolation. The pellet was suspended in 1 ml RNAwiz (Ambion, Austin, TX) and subjected to bead beating for 1 min using a mini-BeadBeater. RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's protocol and cleaned with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Primers used for amplification of ace and ers internal hybridization probes were previously described (13). Primers, del probeF, and del probeR were used for amplification of the grvR hybridization probe (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Mutanolysin cell wall extracts and Western blot analysis.

Surface expression of Ace was detected by Western blot analysis after mutanolysin treatment. Mutanolysin treatment, SDS-PAGE, and Western hybridization with anti-Ace monoclonal antibody 70 were performed as previously described (11, 13).

Adherence assay.

E. faecalis strains were grown for 16 h in BHI at 46°C, harvested, washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), and adjusted to an OD600 of 1.0. Ten micrograms of collagen IV in 100 μl of PBS was used to coat 96-well 4HBX plates (Thermo Scientific, Rochester, NY) overnight at 4°C. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a control. After decanting, each well was blocked with 200 μl of 2% BSA for 2 h at 4°C and washed three times with PBS. A total volume of 100 μl of bacteria (OD600 = 1.0) was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 2 h under static conditions. The wells were washed three times with PBS, and cells were fixed with Bouin's fixation solution (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) for 20 min at room temperature. Each well was washed three times with PBS and stained with 1% (wt/vol) crystal violet for 10 min at room temperature. After three washes with PBS, an ethanol-acetone (8:2 ratio) solution was used to elute the stained dye. The absorbance of each well was measured at 570 nm using a 96-well plate reader (Thermo Labsystems, Vantaa, Finland).

Biofilm assay.

For in vitro biofilm formation assays (15), E. faecalis was grown overnight at 37°C in TSBG, diluted to an initial OD600 of 0.05 in 200 μl TSBG in 96 well 4HBX plates, and incubated for additional 24 h. As described for the adherence assay, E. faecalis was fixed with Bouin's solution for 30 min, stained with 1% crystal violet for 30 min, and solubilized in ethanol-acetone (8:2 ratio) solution to determine the OD570 using the 96-well plate reader.

Mouse urinary tract infection model.

Preparation of mice, E. faecalis OG1RF, and the ΔgrvR and grvR* strains and all other stages of the mixed-infection competition experiments were performed as previously described (19). In brief, wild-type OG1RF versus the ΔgrvR strain and the grvR* strain versus the ΔgrvR strain were tested in a mixed-infection competition assay by inoculating a bacterial mix (estimated as approximately 1:1 by OD, with subsequent CFU determination to determine the actual ratio) intraurethrally via an inserted catheter, and the catheter was removed soon after the inoculation. Animals were sacrificed 48 h after infection, and bacteria were recovered by plating tissue homogenates of kidney pairs and urinary bladders. After 24 to 48 h, all colonies that grew from tissue homogenates (up to 47/mouse and two controls in a 96-well microtiter plate) were picked into wells containing BHI, grown overnight, and then used to prepare DNA lysates from colonies on nylon membranes that were hybridized under high-stringency conditions, using intragenic DNA probes of ace and grvR to generate the percentage of wild type and mutant in the bacteria recovered from kidneys and bladders (15). The animal experimental procedures were preapproved and were carried out in accordance with the institutional policies and the guidelines stipulated by the animal welfare committee, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Statistical analysis.

Differences in biofilm between E. faecalis strains were compared by the Mann-Whitney test. The percentage of the ΔgrvR strain in the inoculum versus the percentage of the ΔgrvR strain in the kidneys and bladders of individual mice coinfected with the ΔgrvR strain and either OG1RF (or the grvR* strain) in the competition assay were analyzed by the paired t test using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

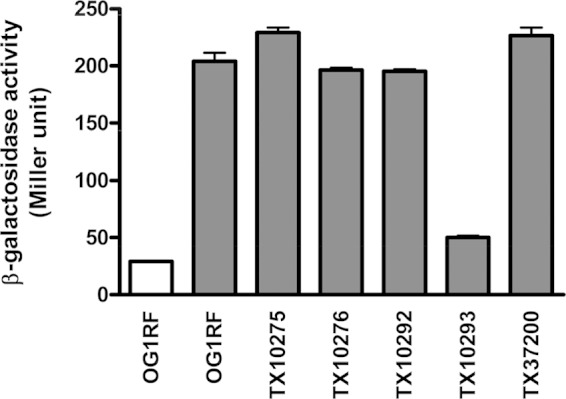

An ace promoter-lacZ fusion indicates that GrvRS regulates ace expression.

Previously, we generated a series of knockout mutants of E. faecalis OG1RF TCS (14). To investigate ace expression in these mutants, we introduced an ace promoter-lacZ fusion (13) into OG1RF and five of its TCS mutants and determined the β-galactosidase activity after growth in BHIS and, for OG1RF, also in BHI (Fig. 1). As expected (8, 13), promoter activity of ace in OG1RF was induced by the presence of serum (Fig. 1), and we found that expression of ace was significantly reduced (about 4-fold) in one of the TCS mutants, TX10293 (Fig. 1). TX10293 contains a polar insertion of a kanamycin resistance transposon that disrupts grvR (14). To confirm the involvement of the GrvRS system in ace expression, we constructed a nonpolar markerless in-frame deletion of grvR (ΔgrvR) in E. faecalis OG1RF. To avoid a possible overdose effect of putting the transcriptional regulator grvR in trans, we complemented (restored) the ΔgrvR strain by reconstituting the chromosomal deletion rather than cloning the gene into a plasmid. In this manner, we also avoided the use of antibiotics to maintain the plasmid. To distinguish the complemented (grvR*) strain from wild-type OG1RF, a silent tagging mutation was introduced into the most abundant amino acid in GrvR, leucine (12.3% of GrvR protein). OG1RF and the ΔgrvR and grvR* strains showed similar growth rates in BHI and in BHIS at 37°C (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Compared to OG1RF and the grvR* strain, the ΔgrvR strain was heat resistant and acid sensitive (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), in agreement with previous results with the disruption mutant TX10293 (14).

FIG 1.

ace promoter activity in TCS mutants of E. faecalis OG1RF. β-Galactosidase activities of OG1RF and its TCS mutants containing pTEX6075b were determined. Measurements were carried out in duplicate in two strains grown in BHI (white bar) or BHIS (gray bars).

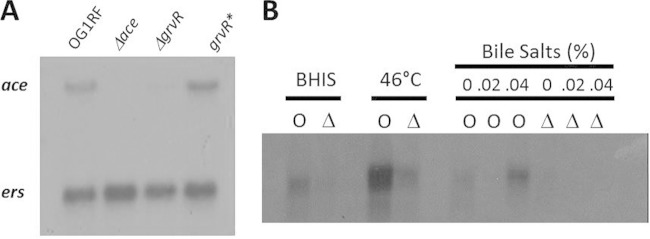

Northern hybridization indicates that ace transcripts are significantly decreased in the ΔgrvR mutant.

Expression of ace in OG1RF and its Δace, ΔgrvR, and grvR* mutants was determined by Northern hybridization under different stress conditions previously shown to increase ace expression (8, 13), with strains grown to mid-exponential phase at 46°C (Fig. 2A). Results showed that ace mRNA was present in OG1RF and the complemented grvR* strain but absent in the Δace strain and barely detectable in the ΔgrvR strain, confirming that GrvR regulates ace expression (Fig. 2A). The ers gene (13) was used as an RNA quality and quantity control.

FIG 2.

Northern hybridization of ace in E. faecalis strains. Northern blot analysis was performed with total RNA (10 μg per lane) and hybridized with internal probes of ace (A and B) and ers (A). The ers gene was used as an RNA quality and quantity control. (A) Strains were grown in BHI at 46°C. (B) OG1RF (O) and the ΔgrvR mutant (Δ) were grown in BHIS at 37°C, in BHI at 46°C, and in BHI with bile salts.

We then investigated expression of ace in OG1RF and the ΔgrvR mutant grown to mid-exponential phase in the presence of serum (BHIS) and in BHI with bile salts (0, 0.02, and 0.04%) at 37°C and at 46°C in BHI (Fig. 2B). Results showed that ace mRNA increased in BHIS and at 46°C compared to that of BHI only. Expression of ace in bile salts was concentration dependent, as only the higher concentration (0.04%) increased ace mRNA. Increased temperature (46°C) resulted in the greatest increase in ace mRNA in OG1RF (Fig. 2B). Under all conditions tested, ace mRNA in the ΔgrvR strain was barely detectable, confirming that GrvR is necessary for ace induction under these conditions. Currently, we do not know whether ace expression is higher at tested stress conditions or the RNA is more stable under these conditions.

Ace surface levels are decreased in the ΔgrvR mutant.

We next investigated whether the level of ace transcripts in the ΔgrvR mutant is correlated with the levels of Ace on the surface and with function. For Western blots of cell wall extracts, OG1RF and its ΔgrvR mutant were grown in the presence of serum. Ace was present in surface extracts of OG1RF but was not detected in surface extracts of the ΔgrvR strain (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

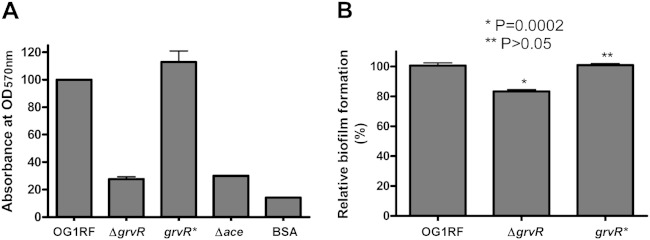

Previous studies have shown that Ace mediates adherence of E. faecalis to ECM proteins such as collagen IV (4, 6). We then performed an adherence assay to investigate the effect of the deletion of grvR on collagen binding using strains grown at 46°C and methods described previously (20). There was no collagen IV binding by the Δace or ΔgrvR strain, whereas wild-type OG1RF and its complemented grvR* strain had comparable levels of binding activity (Fig. 3A). The same binding patterns were observed with collagen I and laminin (data not shown). Previous studies with TX10293 suggested a role for grvR in biofilm formation (21). We found that deletion of grvR modestly but statistically significantly reduced biofilm formation; biofilm-forming ability was restored in the grvR* strain (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Effect of grvR deletion on adherence to collagen IV (A) and biofilm (B). Values for OG1RF were considered 100%, and the relative activities for the other strains are shown. Mean OD570s of OG1RF were 1.048 (A) and 1.733 (B). Bars represent the means and standard deviations from two independent experiments representing six wells for each strain. BSA was used as a control for adherence. P values are for comparison versus OG1RF.

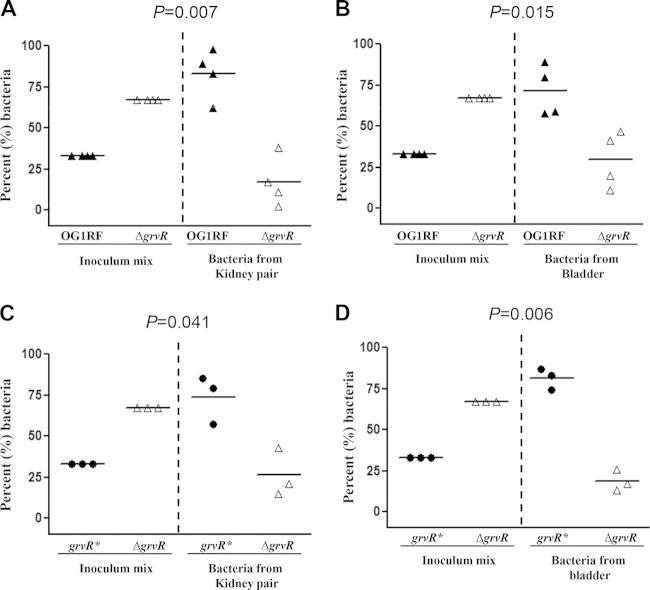

Deletion of grvR causes attenuation in the mouse urinary tract infection.

To further investigate the involvement of GrvRS in virulence of E. faecalis, we used a mixed infection of OG1RF and the ΔgrvR strain in the murine UTI model. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, significantly greater numbers of OG1RF were recovered from both kidneys and bladders. Attenuation of the ΔgrvR strain in the UTI model was restored in the reconstituted (grvR*) strain (Fig. 4C and D). These results indicate that grvR is involved in the pathogenesis of E. faecalis in the murine UTI model.

FIG 4.

Effect of grvR deletion from OG1RF and its restoration in a mouse urinary tract infection using a mixed inoculum. (A and C) Percentage of bacteria recovered from kidneys. (B and D) Percentage of bacteria recovered from bladders. Horizontal bars indicate the means of percentages of each strain in the inoculum and from kidneys and bladders. Percentages were derived from CFU counts of the inoculum mixtures and from the kidney and bladder homogenates and compared using the paired t test. Percentage values are obtained from four (A and B) and three (C and D) mice, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Ace of E. faecalis is expressed during infection and assumed to contribute to infection by adhering to exposed ECM molecules such as collagen and laminin (4, 6, 22–24). Previous work found that expression of ace is dependent on environmental conditions, including the presence of serum and bile salts (8, 9). Bacteria often control gene expression in response to environmental changes via TCSs, which are generally composed of a sensor histidine kinase that recognizes specific environmental signals and a response regulator that mediates a response to gene expression (25, 26). In order to determine whether a TCS is responsible increases in ace expression, we investigated TCSs we had previously studied in E. faecalis (14). With disruption mutation and an ace promoter fusion, we found that GrvRS appeared to control ace expression in respond to serum, leading to the upregulation of ace expression. GrvRS has homology with other TCSs of Gram-positive pathogens, such as CovRS (also called CsrRS) of group A/B streptococci (27–30) and LisRK of Listeria monocytogenes (31, 32), which have been shown to be important for their virulence. The CovRS system shows high similarity with GrvRS (70% for GrvR versus CovR and 54% for GrvS versus CovS) (14, 33). The CovRS system has also been shown to respond to the environmental stimuli produced by blood components (34–36).

A ΔgrvR deletion mutant confirmed the involvement of GrvR in the regulation of ace expression (Fig. 2). In addition, disruption of grvR led to the loss of ECM binding activity and reduced biofilm formation and attenuation in the UTI model (Fig. 3 and 4). Because the ace deletion mutant was also attenuated in the UTI model (6), attenuation of the ΔgrvR mutant in this model could be the consequence of reduced ace expression in the ΔgrvR mutant. Previously, we showed that a grvRS mutant (TX10293) of OG1RF was attenuated in a mouse peritonitis model (14). However, an ace mutant was not attenuated in the same peritonitis model (6), indicating that the GrvRS system regulates other virulence determinants in addition to ace. Indeed, a kat gene encoding catalase was reported to be regulated by the GrvRS system in OG1RF (37). Catalase plays an importance role in protection against cellular oxidative stress by degrading hydrogen peroxide (38). In E. faecalis JH2-2, GrvRS was also reported as a negative regulator of the heat shock proteins DnaK and GroEL (39). Therefore, the GrvRS regulon appears to contain many other genes in addition to the genes mentioned above.

The grvRS region is part of the E. faecalis core genome; of the approximately 250 E. faecalis genome sequences available in the NCBI genomic database, the amino acid sequences of GrvRS are virtually identical in all (data not shown). Therefore, based on the sequence similarity of GrvRS, we expected a similar, if not identical, signaling mechanism of GrvRS in E. faecalis strains. However, studies carried out in different E. faecalis backgrounds, such as JH2-2 and V583, showed differences between strains in the GrvRS system (24, 39, 40). In strains OG1RF and JH2-2 (14, 24, 39), GrvRS was shown to be involved in stress responses, such as high temperature, low pH, and survival in bile salts; however, in E. faecalis V583, the grvR mutant did not show an acid-sensitive or heat resistance phenotype, suggesting the existence of a backup system of GrvRS in V583 (40).

In summary, we show here that GrvRS is a major regulator of ace and important for E. faecalis OG1RF virulence. A better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms controlling virulence gene expression may help us find new strategies to treat and prevent E. faecalis infections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant AI047923 to B.E.M. from the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, NIAID. S.L.L.R. was supported by project number 191452 from the Research Council of Norway.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.02587-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arias CA, Murray BE. 2012. The rise of the enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:266–278. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rich RL, Kreikemeyer B, Owens RT, LaBrenz S, Narayana SV, Weinstock GM, Murray BE, Hook M. 1999. Ace is a collagen-binding MSCRAMM from Enterococcus faecalis. J Biol Chem 274:26939–26945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kowalski WJ, Kasper EL, Hatton JF, Murray BE, Nallapareddy SR, Gillespie MJ. 2006. Enterococcus faecalis adhesin, Ace, mediates attachment to particulate dentin. J Endod 32:634–637. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nallapareddy SR, Qin X, Weinstock GM, Hook M, Murray BE. 2000. Enterococcus faecalis adhesin, Ace, mediates attachment to extracellular matrix proteins collagen type IV and laminin as well as collagen type I. Infect Immun 68:5218–5224. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.9.5218-5224.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebreton F, Riboulet-Bisson E, Serror P, Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B, Torelli R, Hartke A, Auffray Y, Giard JC. 2009. ace, which encodes an adhesin in Enterococcus faecalis, is regulated by Ers and is involved in virulence. Infect Immun 77:2832–2839. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01218-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh KV, Nallapareddy SR, Sillanpaa J, Murray BE. 2010. Importance of the collagen adhesin ace in pathogenesis and protection against Enterococcus faecalis experimental endocarditis. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000716. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Sillanpaa J, Zhao M, Murray BE. 2011. Relative contributions of Ebp pili and the collagen adhesin Ace to host extracellular matrix protein adherence and experimental urinary tract infection by Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF. Infect Immun 79:2901–2910. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00038-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nallapareddy SR, Murray BE. 2006. Ligand-signaled upregulation of Enterococcus faecalis ace transcription, a mechanism for modulating host-E. faecalis interaction. Infect Immun 74:4982–4989. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00476-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shepard BD, Gilmore MS. 2002. Differential expression of virulence-related genes in Enterococcus faecalis in response to biological cues in serum and urine. Infect Immun 70:4344–4352. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4344-4352.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall AE, Gorovits EL, Syribeys PJ, Domanski PJ, Ames BR, Chang CY, Vernachio JH, Patti JM, Hutchins JT. 2007. Monoclonal antibodies recognizing the Enterococcus faecalis collagen-binding MSCRAMM Ace: conditional expression and binding analysis. Microb Pathog 43:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinkston KL, Gao P, Diaz-Garcia D, Sillanpaa J, Nallapareddy SR, Murray BE, Harvey BR. 2011. The Fsr quorum-sensing system of Enterococcus faecalis modulates surface display of the collagen-binding MSCRAMM Ace through regulation of gelE. J Bacteriol 193:4317–4325. doi: 10.1128/JB.05026-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao P, Pinkston KL, Bourgogne A, Cruz MR, Garsin DA, Murray BE, Harvey BR. 2013. Library screen identifies Enterococcus faecalis CcpA, the catabolite control protein A, as an effector of Ace, a collagen adhesion protein linked to virulence. J Bacteriol 195:4761–4768. doi: 10.1128/JB.00706-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen AL, Roh JH, Nallapareddy SR, Hook M, Murray BE. 2013. Expression of the collagen adhesin ace by Enterococcus faecalis strain OG1RF is not repressed by Ers but requires the Ers box. FEMS Microbiol Lett 344:18–24. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teng F, Wang L, Singh KV, Murray BE, Weinstock GM. 2002. Involvement of PhoP-PhoS homologs in Enterococcus faecalis virulence. Infect Immun 70:1991–1996. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.1991-1996.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sillanpaa J, Chang C, Singh KV, Montealegre MC, Nallapareddy SR, Harvey BR, Ton-That H, Murray BE. 2013. Contribution of individual Ebp pilus subunits of Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF to pilus biogenesis, biofilm formation and urinary tract infection. PLoS One 8:e68813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panesso D, Montealegre MC, Rincon S, Mojica MF, Rice LB, Singh KV, Murray BE, Arias CA. 2011. The hylEfm gene in pHylEfm of Enterococcus faecium is not required in pathogenesis of murine peritonitis. BMC Microbiol 11:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kristich CJ, Chandler JR, Dunny GM. 2007. Development of a host-genotype-independent counterselectable marker and a high-frequency conjugative delivery system and their use in genetic analysis of Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid 57:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammerstrom TG, Roh JH, Nikonowicz EP, Koehler TM. 2011. Bacillus anthracis virulence regulator AtxA: oligomeric state, function and CO2-signalling. Mol Microbiol 82:634–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sillanpaa J, Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Prakash VP, Fothergill T, Ton-That H, Murray BE. 2010. Characterization of the ebpfm pilus-encoding operon of Enterococcus faecium and its role in biofilm formation and virulence in a murine model of urinary tract infection. Virulence 1:236–246. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.4.11966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolz C, McDevitt D, Foster TJ, Cheung AL. 1996. Influence of agr on fibrinogen binding in Staphylococcus aureus Newman. Infect Immun 64:3142–3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohamed JA, Huang W, Nallapareddy SR, Teng F, Murray BE. 2004. Influence of origin of isolates, especially endocarditis isolates, and various genes on biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis. Infect Immun 72:3658–3663. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3658-3663.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Duh RW, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. 2000. Diversity of ace, a gene encoding a microbial surface component recognizing adhesive matrix molecules, from different strains of Enterococcus faecalis and evidence for production of ace during human infections. Infect Immun 68:5210–5217. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.9.5210-5217.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang M, Ko YP, Liang X, Ross CL, Liu Q, Murray BE, Hook M. 2013. Collagen-binding microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecule (MSCRAMM) of Gram-positive bacteria inhibit complement activation via the classical pathway. J Biol Chem 288:20520–20531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.454462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller C, Sanguinetti M, Riboulet E, Hebert L, Posteraro B, Fadda G, Auffray Y, Rince A. 2008. Characterization of two signal transduction systems involved in intracellular macrophage survival and environmental stress response in Enterococcus faecalis. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 14:59–66. doi: 10.1159/000106083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung K, Fried L, Behr S, Heermann R. 2012. Histidine kinases and response regulators in networks. Curr Opin Microbiol 15:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hancock L, Perego M. 2002. Two-component signal transduction in Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol 184:5819–5825. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.21.5819-5825.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamy MC, Zouine M, Fert J, Vergassola M, Couve E, Pellegrini E, Glaser P, Kunst F, Msadek T, Trieu-Cuot P, Poyart C. 2004. CovS/CovR of group B streptococcus: a two-component global regulatory system involved in virulence. Mol Microbiol 54:1250–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gryllos I, Grifantini R, Colaprico A, Jiang S, Deforce E, Hakansson A, Telford JL, Grandi G, Wessels MR. 2007. Mg2+ signalling defines the group A streptococcal CsrRS (CovRS) regulon. Mol Microbiol 65:671–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran-Winkler HJ, Love JF, Gryllos I, Wessels MR. 2011. Signal transduction through CsrRS confers an invasive phenotype in group A streptococcus. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002361. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Churchward G. 2007. The two faces of Janus: virulence gene regulation by CovR/S in group A streptococci. Mol Microbiol 64:34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cotter PD, Emerson N, Gahan CG, Hill C. 1999. Identification and disruption of lisRK, a genetic locus encoding a two-component signal transduction system involved in stress tolerance and virulence in Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol 181:6840–6843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cotter PD, Guinane CM, Hill C. 2002. The LisRK signal transduction system determines the sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes to nisin and cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:2784–2790. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.2784-2790.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heath A, DiRita VJ, Barg NL, Engleberg NC. 1999. A two-component regulatory system, CsrR-CsrS, represses expression of three Streptococcus pyogenes virulence factors, hyaluronic acid capsule, streptolysin S, and pyrogenic exotoxin B. Infect Immun 67:5298–5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jadoun J, Eyal O, Sela S. 2002. Role of CsrR, hyaluronic acid, and SpeB in the internalization of Streptococcus pyogenes M type 3 strain by epithelial cells. Infect Immun 70:462–469. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.462-469.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang S-M, Ishmael N, Hotopp JD, Puliti M, Tissi L, Kumar N, Cieslewicz MJ, Tettelin H, Wessels MR. 2008. Variation in the group B Streptococcus CsrRS regulon and effects on pathogenicity. J Bacteriol 190:1956–1965. doi: 10.1128/JB.01677-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wessels MR. 1999. Regulation of virulence factor expression in group A Streptococcus. Trends Microbiol 7:428–430. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(99)01604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baureder M, Hederstedt L. 2012. Genes important for catalase activity in Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS One 7:e36725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baureder M, Reimann R, Hederstedt L. 2012. Contribution of catalase to hydrogen peroxide resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 331:160–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le Breton Y, Boel G, Benachour A, Prevost H, Auffray Y, Rince A. 2003. Molecular characterization of Enterococcus faecalis two-component signal transduction pathways related to environmental stresses. Environ Microbiol 5:329–337. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hancock LE, Perego M. 2004. Systematic inactivation and phenotypic characterization of two-component signal transduction systems of Enterococcus faecalis V583. J Bacteriol 186:7951–7958. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7951-7958.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bourgogne A, Garsin DA, Qin X, Singh KV, Sillanpaa J, Yerrapragada S, Ding Y, Dugan-Rocha S, Buhay C, Shen H, Chen G, Williams G, Muzny D, Maadani A, Fox KA, Gioia J, Chen L, Shang Y, Arias CA, Nallapareddy SR, Zhao M, Prakash VP, Chowdhury S, Jiang H, Gibbs RA, Murray BE, Highlander SK, Weinstock GM. 2008. Large scale variation in Enterococcus faecalis illustrated by the genome analysis of strain OG1RF. Genome Biol 9:R110. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leenhouts K, Buist G, Bolhuis A, ten Berge A, Kiel J, Mierau I, Dabrowska M, Venema G, Kok J. 1996. A general system for generating unlabelled gene replacements in bacterial chromosomes. Mol Gen Genet 253:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.