Abstract

Anatomical and neurophysiological evidence indicates that thoracic interneurons can serve a commissural function and activate contralateral motoneurons. Accordingly, we hypothesized that respiratory-related intercostal (IC) muscle electromyogram (EMG) activity would be only modestly impaired by a unilateral cervical spinal cord injury. Inspiratory tidal volume (VT) was recorded using pneumotachography and EMG activity was recorded bilaterally from the 1st to 2nd intercostal space in anesthetized, spontaneously breathing rats. Studies were conducted at 1–3 days, 2 wks or 8 wks following C2 spinal cord hemisection (C2HS). Data were collected during baseline breathing and a brief respiratory challenge (7% CO2). A substantial reduction in inspiratory intercostal EMG bursting ipsilateral to the lesion was observed at 1–3 days post-C2HS. However, a time-dependent return of activity occurred such that by 2 wks post-injury inspiratory intercostal EMG bursts ipsilateral to the lesion were similar to age-matched, uninjured controls. The increases in ipsilateral intercostal EMG activity occurred in parallel with increases in VT following the injury (R = 0.55; P < 0.001). We conclude that plasticity occurring within a “crossed-intercostal” circuitry enables a robust, spontaneous recovery of ipsilateral intercostal activity following C2HS in rats.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Intercostal, Plasticity

1. Introduction

Following unilateral spinal cord hemisection at the second cervical segment (C2HS), plasticity in phrenic motor pathways results in a modest return of inspiratory activity in the ipsilateral hemi-diaphragm (Fuller et al., 2008) often termed the “crossed-phrenic phenomenon” (Goshgarian, 2009; Lane et al., 2009). However, the contribution of the crossed phrenic phenomenon to tidal volume (VT) appears to plateau by 2-wks post-injury in spontaneously breathing rats (Dougherty et al., 2012). The relatively small contribution of ipsilateral phrenic activity suggests that other motor outputs are critical to maintaining VT after chronic C2HS. For example, the contralateral hemi-diaphragm shows an increase in activity following unilateral diaphragm paralysis (Golder et al., 2001; Katagiri et al., 1994; Miyata et al., 1995; Rowley et al., 2005; Teitelbaum et al., 1993). This increase in contralateral phrenic output occurs very rapidly, and has been attributed to removal of inhibitory inputs from both large and small diameter phrenic afferents (Teitelbaum et al., 1993). Immediate and sustained increases in contralateral hemi-diaphragm activity probably sustain VT in the short term, but also may limit the ability of the contralateral phrenic motor pool to facilitate progressive (i.e., weeks–months) increases in VT after chronic spinal cord injury (Doperalski and Fuller, 2006; Fuller et al., 2006). In this scenario, time-dependent increases in the output of the accessory inspiratory muscles, such as the external intercostals (IC) (De Troyer et al., 2005), may be the primary contributor to any spontaneous increases in VT that may occur after the initial days–weeks following C2HS.

The thoracic spinal cord contains an extensive population of propriospinal interneurons that receive respiratory-related synaptic inputs (Kirkwood et al., 1984; Qin et al., 2002; Saywell et al., 2011). An increasing body of evidence suggests that these cells are ideal candidates to serve as a “synaptic relay” of inspiratory drive to intercostal motoneurons following partial interruption of bulbospinal respiratory pathways (Saywell et al., 2011). For example, a recent study found that thoracic interneurons with inspiratory discharge patterns almost always have an axonal projection extending across the spinal midline (Saywell et al., 2011). This anatomical feature is consistent with neurophysiological evidence (Kirkwood et al., 1988) that thoracic interneurons can modulate respiratory motoneuron output in the contralateral spinal cord. Thus, both anatomical and neurophysiological data suggest that thoracic interneurons can relay respiratory synaptic drive across the spinal midline. Accordingly, our primary purpose was to test the hypothesis that unilateral high cervical spinal cord injury (i.e., C2HS) would only modestly impair the inspiratory-related electromyogram (EMG) recorded in the ipsilateral intercostal muscles during spontaneous breathing in rats. Our secondary purpose was to explore the temporal relationship between the amplitude of ipsilateral IC EMG activity and inspiratory VT over the days–weeks following C2HS injury. Since the ipsilateral hemi-diaphragm makes only a modest contribution to VT following chronic C2HS (Dougherty et al., 2012; Fuller et al., 2008), we reasoned that the intercostal muscles are making a substantial contribution to the respiratory recovery process.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

A total of 27 adults, male Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Harlan Laboratories Inc. (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Rats receiving C2HS were grouped according to the time of post-injury evaluation as follows: “acute” (1–3 days, n = 4), 2 wks (n = 8) or 8 wks (n = 8). Spinal-intact rats were age-matched to either 2 wks (n = 3) or 8 wks (n = 4) C2HS rats and combined into a single control group. A summary of experimental groups is presented in Table 1. Experiments were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee at the University of Florida.

Table 1.

Age, weight (wgt), arterial blood gases and mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) from spontaneously breathing, spinal-intact control rats and rats 1-3 days, 2 wks, and 8 wks post-C2HS.

| Control | 1-3 days | 2 wks | 8 wks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (days) | 133 ± 39 | 97 ± 1 | 111 ± 1 | 157 ± 2 |

| wgt (g) | 371 ± 24 | 326 ± 18 | 348 ± 7 | 396 ± 11 |

| PaO2 (mm/Hg) | 190 ± 18 | 207 ± 7 | 204 ± 10 | 166 ± 10 |

| PaCO2 (mm/Hg) | 39 ±2 | 65 ± 7*** | 45 ± 2 | 44 ± 2 |

| pH | 7.31 ± 0.02 | 7.19 ± 0.04* | 7.32 ± 0.02 | 7.28 ± 0.02 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 95 ±6 | 75 ± 7 | 81 ± 5 | 83 ± 6 |

P <0.001

P <0.05 from all other groups.

2.2. Spinal cord injury

The surgical methods used to produce the C2HS injury are consistent with our prior reports (Dougherty et al., 2012; Fuller et al., 2008, 2009). Rats were anesthetized with xylazine (10 mg/kg, s.q.) and ketamine (140 mg/kg, i.p., Fort Dodge Animal Health, IA, USA). The spinal cord was exposed at the C2 level via a dorsal approach and a left C2HS lesion was induced using a microscalpel followed by aspiration. The dura and overlying muscles were sutured and the skin closed with stainless steel wound clips (Stoelting, IL, USA). Rats were given an injection of yohimbine (1.2 mg/kg, s.q., Lloyd, IA, USA) to reverse the effect of xylazine. Following surgery, animals received an analgesic (buprenorphine, 0.03 mg/kg, s.q., Hospira, IL, USA) and sterile lactated Ringers solution (5 ml s.q.). Post-surgical care included administration of buprenorphine (0.03 mg/kg, s.q.) during the initial 48 h post-injury and delivery of lactated Ringers solution (5 ml/day, s.q.) and oral Nutri-cal supplements (1–3 ml, Webster Veterinary, MA, USA) as needed until adequate volitional drinking and eating resumed.

2.3. Experimental preparation

These procedures were adapted from prior publications (Dougherty et al., 2012; Fuller et al., 1998). Isoflurane anesthesia (3–4% in O2) was induced in a closed chamber followed by i.p. injection of urethane (1.6 g/kg, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The adequacy of urethane anesthesia was confirmed by absence of limb withdrawal and palpebral reflexes. Rats were maintained in a supine position throughout the protocol and body temperature was maintained at 37.5 ± 1 °C using a servo-controlled heating pad (model TC-1000, CWE Inc., Ardmore, PA, USA). The trachea was cannulated in the mid-cervical region and connected in series to a custom designed, small animal pneumotachograph and volumetric pressure transducer (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA, USA) for measurement of respiratory air flow. Calibration of the pneumotachograph was accomplished using a series of constant volume injections with varying airflow rates as previously described (Dougherty et al., 2012). Respiratory airflow signals were amplified (×100 K; CP122 AC/DC strain gage amplifier, Grass Instruments) and recorded using Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design Limited). The inspiratory phase of the airflow signals were integrated (∫ flow) using a customized Spike2 software script (Cambridge Electronic Design Limited) and VT was then calculated off-line. Partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) was maintained above 150 mmHg by delivering a hyperoxic gas mixture (50% O2, balance N2; flow rate ~1.0 L/min) to the tracheostomy tube via a “T-piece” design (Fuller et al., 1998). The femoral vein was catheterized (PE-50 tubing) to enable supplemental urethane anesthesia (0.3 g/kg, i.v., Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) if indicated. Another PE-50 catheter was placed in the femoral artery for arterial pressure and blood gas measurements.

Since inspiratory activity is more robust in rostral vs. caudal intercostal spaces (Butler and Gandevia, 2008; Gandevia et al., 2006), we recorded EMG activity of rostral inspiratory intercostal muscles of the first or second rib space. Bilateral rostral intercostal muscles were exposed ventrolaterally following reflection of overlying pectoral musculature from sternal midline. EMG electrodes were fabricated from Teflon coated tungsten wire (A-M Systems, Sequim, WA, USA). Wire was threaded through a 25 gauge hypodermic needle (Tyco Healthcare, Mansfield, MA, USA) and the ends (~2–3 mm) stripped of their Teflon coating. EMG electrodes were inserted bilaterally into external intercostal muscles of the first or second intercostal space to record inspiratory muscle activation. EMG burst signals were matched to the inspiratory airflow trace to confirm accurate placement in the external intercostals. Electrical activity recorded from the electrodes placed in the intercostal muscles was amplified (1000×) and filtered (band pass: 300–10,000 Hz; notch: 60 Hz) using a differential A/C amplifier (Model 1700, A-M Systems, Carlsborg, WA, USA). The signal was also rectified and moving averaged (time constant 100 ms; MA-1000 moving averager, CWE Inc., Ardmore, PA, USA). All signals were digitized and recorded on a PC using Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design Limited).

Arterial blood samples (0.2 ml) were drawn during the baseline period (see experimental protocols) and analyzed for PaO2, carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2) and pH (i-STAT, Waukesha, WI, USA). Blood gas measures were corrected to rectal temperature.

2.4. Experimental protocol

Baseline EMG activity was recorded over a 20 min period during which rats breathed the hyperoxic gas mixture described above. This baseline period was followed by a 5-min hypercapnic respiratory challenge (7% CO2, 50% O2, balance N2). Arterial blood gas samples were taken just prior to hypercapnic respiratory challenge. Following completion of EMG studies, rats were euthanized by systemic perfusion with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The cervical spinal cord was removed, and 40 μm sections were made in the transverse plane using a vibrotome. Tissue sections were mounted on glass slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), stained with Cresyl violet and evaluated by light microscopy. Consistent with our previous publications (Dougherty et al., 2012; Fuller et al., 2008, 2009; Lane et al., 2008b; Sandhu et al., 2009), the complete absence of white and gray matter in the ipsilateral C2 spinal cord was taken as confirmation of an anatomically complete C2HS (not shown) (Fuller et al., 2009).

2.5. Data analyses

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare body weight, blood gases, and mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) across groups. Respiratory parameters including inspiratory duration (TI), expiratory duration (TE), respiratory frequency (fR), VT and minute ventilation (VE) during baseline and hypercapnic respiratory challenge were compared using two-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA and Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test. For this two-way RM ANOVA, factor 1 was treatment (i.e. control or lesion group), and factor 2: condition (baseline or respiratory challenge). For statistical analyses of bilateral integrated intercostal EMG activity, a 30 s period of stable bursting during baseline and within the last minute of hypercapnic respiratory challenge were analyzed using two-way RM ANOVA with factors of time post-C2HS and condition (i.e. baseline or hypercapnia). Ipsilateral intercostal EMG signals were expressed as arbitrary units (a.u.) and relative to contralateral signals (% contralateral) during both baseline and hypercapnic challenge. The data expressed as % contralateral were not normally distributed, therefore, a one-way ANOVA on-ranks and the Dunn's method for pair-wise multiple comparisons was used for each condition. Linear regression analyses were used to examine the relationships between recovery of intercostal EMG activity and VT following C2HS. All data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Age, body weight and blood gases

Age and body weight are presented in Table 1. These values were not significantly different between groups (P > 0.05) although rats at 8 wks post-C2HS tended to be heavier than those in the 1–3 days and 2 wks groups. Accordingly, VT data are presented as both ml/breath and ml/breath/100 g body weight. Similar to previous reports (Dougherty et al., 2012) acutely injured rats showed evidence of respiratory acidosis as reflected by increased PaCO2 (P < 0.001) and decreased pH (P < 0.05) compared with other groups (Table 1).

3.2. Effects of C2HS on ventilation

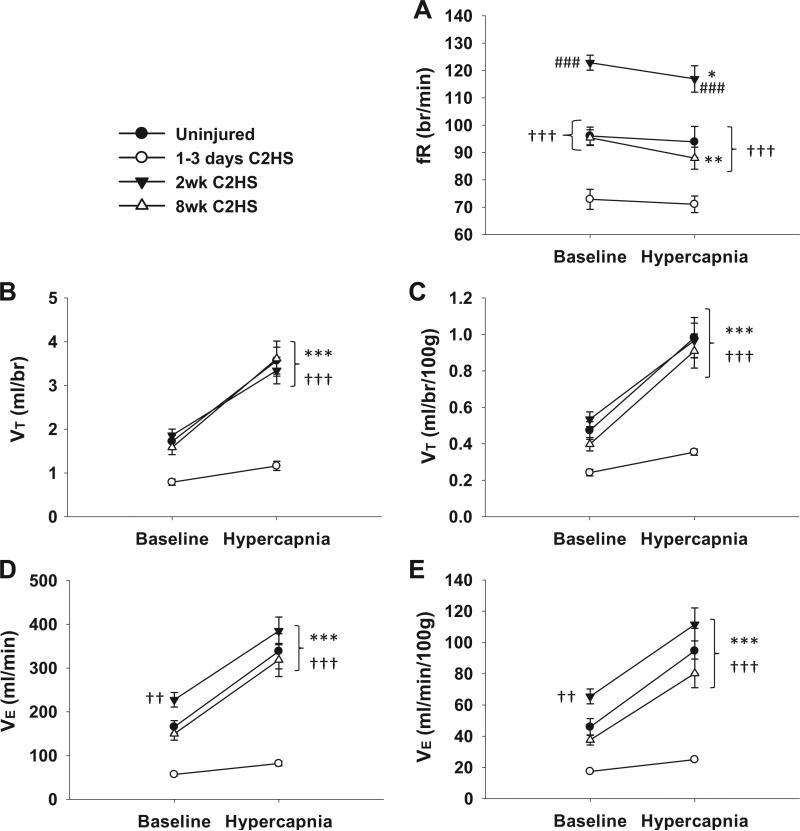

Rats had reduced ventilation at 1–3 days following C2HS (P < 0.001) which was manifested through reductions in both fR and VT (Fig. 1). fR was blunted during both baseline (P < 0.001) and hypercapnic challenge (P < 0.001, Fig. 1A) due to elongated TE (P < 0.01, Table 2). VT was also diminished during both conditions in the acutely injured group (Fig. 1B and C). Hypoventilation was no longer present at 2 wks post-injury. In fact, an increase in fR was observed at 2 wks post-C2HS (Fig. 1A) as a result of shortened TE (P < 0.05) (Table 2). The increased fR in the 2 wks post-C2HS group resulted in increased VE during baseline conditions (Fig. 1D and E). This increase in fR was transient, however, as both fR and TE (Table 2) returned to values similar to uninjured rats by 8 wks post-C2HS.

Fig. 1.

The effects of C2HS on ventilation. Acutely following C2HS (i.e. 1–3 days) rats exhibited reduced frequency (fR), tidal volume (VT) and minute ventilation (VE) during baseline and hypercapnic challenge. Two weeks post-C2HS, a transient elevation in fR was noted during both conditions (A) triggering enhanced VE during baseline (D and E), while VT returned to control levels (B and C). Normalization of fR (A) and sustained VT recovery (B and C) persisted at 8 wks post-C2HS. VT and VE are expressed as mean values (B and D) and mean values relative to body mass (C and E). ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 from baseline values; ###P < 0.001 from all other groups; †††P < 0.001, ††P < 0.01, †P < 0.05 from 1–3 days C2HS group.

Table 2.

Inspiratory (TI) and expiratory (TE) duration during spontaneous breathing in spinal-intact control rats and rats 1-3 days, 2 wks, and 8 wks post-C2HS.

| Baseline | ||

|---|---|---|

| TI (s) | TE (s) | |

| Control | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.02 |

| 1-3 days | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.55 ± 0.06** |

| 2 wks | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01* |

| 8 wks | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.04 |

| Hypercapnia | ||

| Control | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.39 ± 0.03 |

| 1-3 days | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.57 ± 0.07* |

| 2 wks | 0.24 ± 0.01+ | 0.28 ± 0.02+** |

| 8 wks | 0.28 ± 0.02++ | 0.41 ± 0.05+ |

P<0.01

P <0.05 from all other groups

P <0.01

P <0.05 from baseline.

A time-dependant increase in VT occurred by 2 wks post-C2HS resulting in values similar to control animals, and VT remained at similar levels at 8 wks post-injury (Fig. 1B and C). Assessment of VT using two-way RM ANOVA revealed an interaction between time post-C2HS and condition (i.e. baseline or hypercapnia, P < 0.05). This result was not related to body mass, as the interaction remained regardless of whether data was expressed as ml/br (P = 0.009) or ml/br/100 g (P = 0.022). The significant interaction indicates that the effects of hypercapnia were dependent upon the time post-injury. This is evident from Fig. 1 which illustrates that the hypercapnic ventilatory response was much more robust at 2 and 8 wks post-injury as compared to the acute injury group.

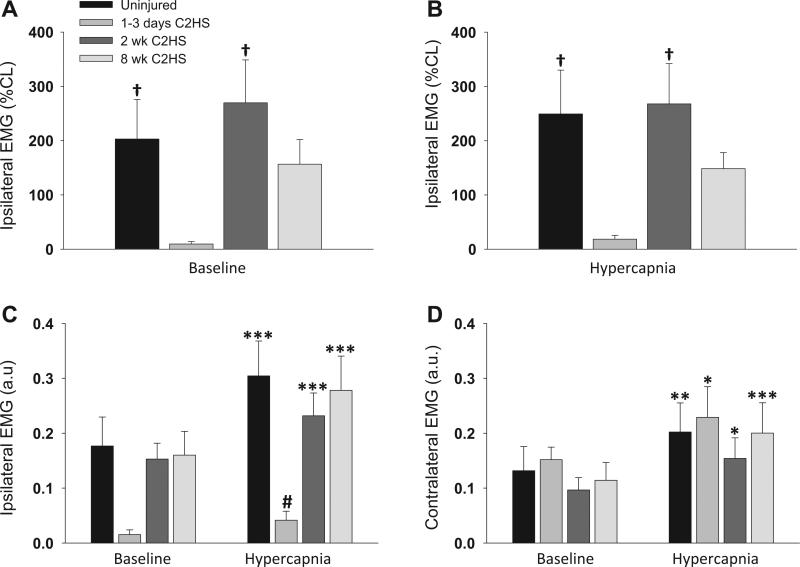

3.3. Effects of C2HS on intercostal EMG

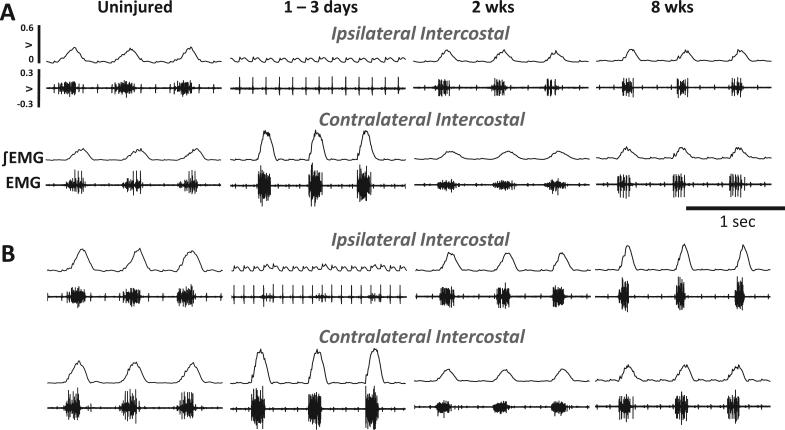

Representative examples of intercostal EMG activity are provided in Fig. 2; quantitative comparisons are illustrated in Fig. 3. As expected, uninjured control rats demonstrated inspiratory bursting during both baseline and hypercapnic challenge (Figs. 2 and 3). Expressing the ipsilateral (left) EMG burst as a percentage of contralateral (right) signal suggested a tendency for uninjured control rats to preferentially activate the ipsilateral intercostals during baseline and hypercapnia (Fig. 3C and D). However, the raw amplitudes (i.e., a.u.) of the ipsilateral and contralateral EMG signals were similar during both conditions (P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Examples of rostral inspiratory intercostal EMG during poikilocapnic baseline and hypercapnic respiratory challenge. The images show the raw (EMG) and integrated EMG (∫ EMG) signals from a control (uninjured) rat, and rats studied 3 days, 2 wks and 8 wks following C2HS injury. C2HS resulted in decreased ipsilateral EMG activity 3 days post-C2HS during baseline (A) and hypercapnic challenge (B). However, robust return of ipsilateral (IL) EMG was observed by 2 wks and persisted 8 wks post-C2HS. In these examples, there appears to be a modest attenuation of contralateral (CL) intercostal EMG activity in 2 wks and 8 wks rats following an initial robust increase following C2HS.

Fig. 3.

The effect of C2HS on rostral intercostal EMG amplitude during baseline breathing and hypercapnic respiratory challenge. Ipsilateral EMG amplitudes during baseline and hypercapnic challenge were expressed relative to the contralateral EMG burst (% CL, A and B). These data indicate that following C2HS the ipsilateral inspiratory EMG burst amplitude was transiently reduced. However, ipsilateral EMG amplitudes recovered by 2 wks post-C2HS. A similar conclusion is reached when examining the EMG amplitude data expressed as arbitrary units (a.u.) (C and D). The C2HS injury caused little change in contralateral intercostal EMG amplitudes compared with uninjured controls (D). ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared to corresponding baseline value for that group; #P < 0.05 compared to other groups; †P < 0.05 compared to the 1–3 days post-C2HS group.

The ipsilateral intercostal EMG burst was minimal or absent acutely following C2HS (Fig. 2). On average, at 1–3 days post-injury the ipsilateral EMG burst amplitude (% contralateral burst) was significantly blunted during both baseline and hypercapnia (P < 0.05 vs. uninjured; Fig. 3A and B). When expressed as a.u., the ipsilateral EMG burst tended to be reduced at baseline, and was significantly reduced during hypercapnia (P < 0.05 vs. uninjured, Fig. 3C). Rats did not appear to compensate for acute reductions in ipsilateral intercostal activity with enhanced contralateral EMG activity. Specifically, the contralateral EMG burst was similar to controls during both baseline and hypercapnic challenge at the 1–3 days time point (Fig. 3D).

By 2 wks post-C2HS, a robust inspiratory EMG signal could be recorded in the ipsilateral intercostals during both baseline and hypercapnic challenge (Fig. 2A and B). The ipsilateral EMG burst amplitudes in the 2 wks group were quantitatively similar to the EMG signal in control rats (Fig. 3A and B). The robust inspiratory EMG bursting persisted at 8 wks post-C2HS. Specifically, ipsilateral EMG amplitude was similar to control rats and 2 wks C2HS rats during both baseline and hypercapnic challenge (Fig. 3A and B). Contralateral intercostal EMG output was not significantly different from control, uninjured rats at 2 or 8 wks post-injury (Fig. 3C).

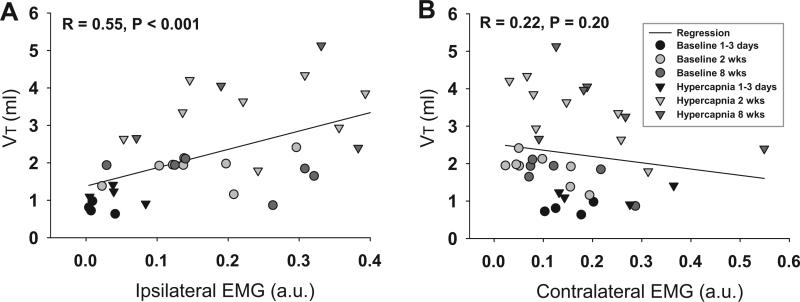

The recovery of VT and ipsilateral intercostal EMG bursting appeared to follow a similar time course following the C2HS injury. Linear regression analysis was therefore used to examine the relationship between these two variables (Fig. 4A and B). A significant and positive correlation was noted (R = 0.55; P < 0.001; Fig. 4A), and this finding suggests that ipsilateral intercostal EMG activity is predictive of VT in the chronic C2HS model. No relationship was detected between contralateral intercostal activity and VT (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Relationship between VT recovery and intercostal EMG bursting following C2HS. A linear regression analysis suggested a strong positive correlation between ipsilateral (IL) EMG activity and recovery of VT (P < 0.001, A). Conversely, no clear relationship exists between contralateral (CL) EMG activity and VT following C2HS (B).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates spontaneous recovery of ipsilateral intercostal EMG activity following unilateral cervical spinal cord injury in rats. This response presumably occurred via a “crossed spinal” pathway, and appears to be considerably more robust than the well described crossed-phrenic phenomenon (Dougherty et al., 2012; Fuller et al., 2008; Goshgarian, 2009; Lane et al., 2008a). Propriospinal interneurons are more prominent in the neural regulation of intercostal vs. phrenic motoneurons (Kirkwood et al., 1984) and accordingly these cells are likely candidates to modulate intercostal motor output and recovery after spinal cord injury (Saywell et al., 2011). We also noted a strong correlation between ipsilateral intercostal EMG activity and VT following C2HS. This observation supports the hypothesis that the intercostal muscles make a significant contribution to respiratory recovery after chronic cervical spinal cord injury (Dougherty et al., 2012; Fuller et al., 2006; Golder et al., 2003).

4.1. Progressive recovery of ipsilateral intercostal EMG activity following C2HS

Respiratory-related intercostal EMG activity was absent in the initial days following C2HS injury. It is unlikely that this response occurred due to “spinal shock” associated with the injury (Ditunno et al., 2004) since similar recordings were obtained at both 1 and 3 days post-injury when local spinal conditions are likely to be quite different (Ditunno et al., 2004). In addition, the thoracic motoneuron pools are substantially removed from the lesion epicenter which may reduce the influence of spinal shock on these cells. Thus, we feel that the most likely explanation for the absence of ipsilateral EMG output during the acute phase is that the primary respiratory bulbospinal inputs to thoracic intercostal motoneurons reside in the ipsilateral spinal cord in this preparation (De Troyer et al., 2005). There are several possibilities regarding the anatomical substrate enabling the return of inspiratory intercostal motoneuron activity following C2HS. First, a monosynaptic projection may exist between the brainstem and thoracic spinal cord which crosses the spinal midline caudal to the spinal lesion (i.e. C2). Such projections have been documented for the phrenic motor pool using anatomical methods (Goshgarian and Rafols, 1984). While there is evidence for monosynaptic bulbospinal inputs to inter-costal motoneurons (Lipski and Duffin, 1986; Vaughan and Kirkwood, 1997) to our knowledge the existence of a “crossed spinal” monosynaptic pathway has not been confirmed. While this remains a possibility, recent work from our group (Lane et al., 2008b; Sandhu et al., 2009) and others (Marchenko and Rogers, 2011) have highlighted the possibility that spinal interneurons contribute to the activation of respiratory motoneurons following chronic spinal cord injury. This is a particularly attractive hypothesis in regards to intercostal motor recovery after spinal lesions (Saywell et al., 2011). Indeed, even in the spinal intact condition there is strong evidence that propriospinal neurons are a major contributor to respiratory-related intercostal motoneuron output (Davies et al., 1985; Lu et al., 2004; Merrill and Lipski, 1987; Qin et al., 2002). Moreover, a recent study from Kirkwood's laboratory reported that most thoracic interneurons show respiratory-related drive potentials, and intracellular filling techniques revealed that a majority of these cells send an axonal projection across the spinal midline (Saywell et al., 2011). Accordingly, these cells are strong candidates for modulating intercostal motor output after spinal cord injury, and our working hypothesis is that plasticity within the thoracic interneuron pool led to the robust recovery of ipsilateral intercostal EMG activity by 2 wks following the C2HS injury. Such plasticity may not be limited to intercostal motor circuits since Jefferson et al. (2010) recently showed that abdominal EMG activity during cough is similar on both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides following a chronic thoracic hemilesion in cats (Jefferson et al., 2010).

4.2. Spontaneous VT recovery following C2HS

The changes in VT that occurred over days–weeks post-C2HS had some differences from previous reports. Specifically, we noted that VT had fully recovered to values observed in uninjured rats by just 2 wks post-C2HS. A prior study from our group found that VT continued to increase between 2 and 8 wks following C2HS (Dougherty et al., 2012). Thus, for reasons that cannot be definitively discerned, the current cohort of rats showed a more accelerated rate of respiratory recovery following the injury. There are a few potential mechanisms which may have contributed to this observation. First, the control rats had reduced arterial PaCO2 during baseline, poikilocapnic breathing (Table 1) as compared to our previous study (Dougherty et al., 2012). There is thus a potential difference in chemoafferent stimulation which could account for VT variability between the two studies. Another consideration is that differential responses to respiratory stimulation can reflect genetic variability among groups of experimental rats. Indeed, the amplitude of phrenic nerve bursting and extent of phrenic motor plasticity (i.e. long-term facilitation) varies among different strains of rats (Golder et al., 2005) and even across colonies of Sprague-Dawely rats from the same vendor (Fuller et al., 2001). In any case, despite the temporal variability in VT recovery between the current study and prior results, the fundamental conclusion remains consistent. Namely, VT shows a substantial reduction after C2HS injury and then shows a time-dependent and spontaneous recovery. The strong positive relationship between ipsilateral intercostal EMG activity and VT demonstrated in the current study supports the hypothesis that inspiratory intercostal muscles are a primary contributor to recovery of VT after C2HS.

4.3. Significance

While respiratory neuroplasticity has been extensively investigated over the last two decades (Baker-Herman et al., 2004; Fuller et al., 2000; Mitchell and Johnson, 2003), there have been few studies of plasticity in the intercostal motor system. The current data suggest that the intercostal motor circuitry is capable of a remarkable degree of plasticity following high cervical SCI. Our working hypothesis is this plasticity enables the intercostal muscles to play an integral role in the recovery of ventilation following cervical SCI, and we speculate that following SCI the intercostal motor system is functionally more important than the well-described cross-phrenic phenomenon (Goshgarian, 2003, 2009). We suggest that the limited data available indicate that the intercostal motor system is capable of a greater degree of plasticity than the phrenic motor system (Fregosi and Mitchell, 1994).

Acknowledgements

B.J. Dougherty was supported by an NIH NRSA pre-doctoral Fellowship 1F31NS063659-01A2. Additional support was provided by NIH grants 1R21-HL104294-01 (DDF) and 1R01-NS-054025 (PJR). EGR was supported by an NIH training grant (T-32 HD043730).

References

- Baker-Herman TL, Fuller DD, Bavis RW, Zabka AG, Golder FJ, Doperalski NJ, Johnson RA, Watters JJ, Mitchell GS. BDNF is necessary and sufficient for spinal respiratory plasticity following intermittent hypoxia. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7:48–55. doi: 10.1038/nn1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JE, Gandevia SC. The output from human inspiratory motoneurone pools. Journal of Physiology. 2008;586:1257–1264. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JG, Kirkwood PA, Sears TA. The distribution of monosynaptic connexions from inspiratory bulbospinal neurones to inspiratory motoneurones in the cat. Journal of Physiology. 1985;368:63–87. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Troyer A, Kirkwood PA, Wilson TA. Respiratory action of the intercostal muscles. Physiological Reviews. 2005;85:717–756. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditunno JF, Little JW, Tessler A, Burns AS. Spinal shock revisited: a four-phase model. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:383–395. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doperalski NJ, Fuller DD. Long-term facilitation of ipsilateral but not contralateral phrenic output after cervical spinal cord hemisection. Experimental Neurology. 2006;200:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty BJ, Lee KZ, Lane MA, Reier PJ, Fuller DD. Contribution of the spontaneous crossed-phrenic phenomenon to inspiratory tidal volume in spontaneously breathing rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2012;112:96–105. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00690.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregosi RF, Mitchell GS. Long-term facilitation of inspiratory intercostal nerve activity following carotid sinus nerve stimulation in cats. Journal of Physiology. 1994;477(Pt 3):469–479. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller D, Mateika JH, Fregosi RF. Co-activation of tongue protrudor and retractor muscles during chemoreceptor stimulation in the rat. Journal of Physiology. 1998;507(Pt 1):265–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.265bu.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Bach KB, Baker TL, Kinkead R, Mitchell GS. Long term facilitation of phrenic motor output. Respiration Physiology. 2000;121:135–146. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Baker TL, Behan M, Mitchell GS. Expression of hypoglossal long-term facilitation differs between substrains of Sprague-Dawley rat. Physiological Genomics. 2001;4:175–181. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.4.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Doperalski NJ, Dougherty BJ, Sandhu MS, Bolser DC, Reier PJ. Modest spontaneous recovery of ventilation following chronic high cervical hemisection in rats. Experimental Neurology. 2008;211:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Golder FJ, Olson EB, Mitchell GS. Recovery of phrenic activity and ventilation after cervical spinal hemisection in rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2006;100:800–806. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00960.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Sandhu MS, Doperalski NJ, Lane MA, White TE, Bishop MD, Reier PJ. Graded unilateral cervical spinal cord injury and respiratory motor recovery. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 2009;165:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandevia SC, Hudson AL, Gorman RB, Butler JE, De Troyer A. Spatial distribution of inspiratory drive to the parasternal intercostal muscles in humans. Journal of Physiology. 2006;573:263–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.101915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ, Fuller DD, Davenport PW, Johnson RD, Reier PJ, Bolser DC. Respiratory motor recovery after unilateral spinal cord injury: eliminating crossed phrenic activity decreases tidal volume and increases contralateral respiratory motor output. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:2494–2501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02494.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ, Reier PJ, Bolser DC. Altered respiratory motor drive after spinal cord injury: supraspinal and bilateral effects of a unilateral lesion. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:8680–8689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08680.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ, Zabka AG, Bavis RW, Baker-Herman T, Fuller DD, Mitchell GS. Differences in time-dependent hypoxic phrenic responses among inbred rat strains. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;98:838–844. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00984.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian HG. The crossed phrenic phenomenon: a model for plasticity in the respiratory pathways following spinal cord injury. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;94:795–810. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00847.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian HG. The crossed phrenic phenomenon and recovery of function following spinal cord injury. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 2009;169:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian HG, Rafols JA. The ultrastructure and synaptic architecture of phrenic motor neurons in the spinal cord of the adult rat. Journal of Neurocytology. 1984;13:85–109. doi: 10.1007/BF01148320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson SC, Tester NJ, Rose M, Blum AE, Howland BG, Bolser DC, Howland DR. Cough following low thoracic hemisection in the cat. Experimental Neurology. 2010;222:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri M, Young RN, Platt RS, Kieser TM, Easton PA. Respiratory muscle compensation for unilateral or bilateral hemidiaphragm paralysis in awake canines. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994;77:1972–1982. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.4.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA, Munson JB, Sears TA, Westgaard RH. Respiratory interneurones in the thoracic spinal cord of the cat. Journal of Physiology. 1988;395:161–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA, Sears TA, Westgaard RH. Restoration of function in external intercostal motoneurones of the cat following partial central deafferentation. Journal of Physiology. 1984;350:225–251. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA, Fuller DD, White TE, Reier PJ. Respiratory neuroplasticity and cervical spinal cord injury: translational perspectives. Trends in Neurosciences. 2008a;31:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA, Lee KZ, Fuller DD, Reier PJ. Spinal circuitry and respiratory recovery following spinal cord injury. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 2009;169:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA, White TE, Coutts MA, Jones AL, Sandhu MS, Bloom DC, Bolser DC, Yates BJ, Fuller DD, Reier PJ. Cervical prephrenic interneurons in the normal and lesioned spinal cord of the adult rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2008b;511:692–709. doi: 10.1002/cne.21864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipski J, Duffin J. An electrophysiological investigation of propriospinal inspiratory neurons in the upper cervical cord of the cat. Experimental Brain Research. 1986;61:625–637. doi: 10.1007/BF00237589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F, Qin C, Foreman RD, Farber JP. Chemical activation of C1–C2 spinal neurons modulates intercostal and phrenic nerve activity in rats. American Physiological Society American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory. 2004;286:R1069–R1076. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00427.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchenko V, Rogers RF. Local spinal GABAergic mechanisms regulate expiratory phrenic nerve activity. FASEB Journal. 2011;25:653, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill EG, Lipski J. Inputs to intercostal motoneurons from ventrolateral medullary respiratory neurons in the cat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1987;57:1837–1853. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.57.6.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GS, Johnson SM. Neuroplasticity in respiratory motor control. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;94:358–374. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00523.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata H, Zhan WZ, Prakash YS, Sieck GC. Myoneural interactions affect diaphragm muscle adaptations to inactivity. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1995;79:1640–1649. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.5.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, Farber JP, Chandler MJ, Foreman RD. Chemical activation of C(1)–C(2) spinal neurons modulates activity of thoracic respiratory interneurons in rats. American Physiological Society American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory. 2002;283:R843–R852. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00054.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley KL, Mantilla CB, Sieck GC. Respiratory muscle plasticity. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 2005;147:235–251. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu MS, Dougherty BJ, Lane MA, Bolser DC, Kirkwood PA, Reier PJ, Fuller DD. Respiratory recovery following high cervical hemisection. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology. 2009;169:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saywell SA, Ford TW, Meehan CF, Todd AJ, Kirkwood PA. Electrophysiological and morphological characterization of propriospinal interneurons in the thoracic spinal cord. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2011;105:806–826. doi: 10.1152/jn.00738.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum J, Borel CO, Magder S, Traystman RJ, Hussain SN. Effect of selective iaphragmatic paralysis on the inspiratory motor drive. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1993;74:2261–2268. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.5.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CW, Kirkwood PA. Evidence from motoneurone synchronization for disynaptic pathways in the control of inspiratory motoneurones in the cat. Journal of Physiology. 1997;503(Pt 3):673–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.673bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]