Abstract

Breast cancer has a relatively high mortality rate in women due to recurrence and metastasis. Increasing evidence has identified a rare population of cells with stem cell-like properties in breast cancer. These cells, termed cancer stem cells (CSCs), which have the capacity for self-renewal and differentiation, contribute significantly to tumor progression, recurrence, drug resistance and metastasis. Clarifying the mechanisms regulating breast CSCs has important implications for our understanding of breast cancer progression and therapeutics. A strong connection has been found between breast CSCs and epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT). In addition, recent studies suggest that the maintenance of the breast CSC phenotype is associated with epigenetic and metabolic regulation. In this review, we focus on recent discoveries about the connection between EMT and CSC, and advances made in understanding the roles and mechanisms of epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming in controlling breast CSC properties.

Keywords: Cancer stem cells (CSCs), Epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT), Epigenetic modification, Metabolic reprogramming, Breast cancer

1. Introduction

Despite medical advances in early detection and treatment, breast cancer still has a relatively high mortality rate in women due to recurrence and metastasis (Jemal et al., 2011). Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease. This heterogeneity is found not only among different breast tumor subtypes (interheterogeneity) but also within the same tumor (intraheterogeneity) (Almendro and Fuster, 2011). A high degree of diversity between and within tumors, as well as among cancer-bearing individuals, determines the risk of cancer progression and therapeutic resistance (Polyak, 2011). A growing body of evidence has demonstrated that this heterogeneity may originate from the existence of a rare population of cells with stem cell-like properties in many cancer types, including breast cancer. However, only recently has the cancer stem cell (CSC) hypothesis been supported by biomedical advances. It has been proposed that solid tumors contain a minor proportion of undifferentiated cells with the ability to initiate tumors due to the capacity for self-renewal and differentiation in their progeny. These CSCs, or tumor-initiating cells (TICs), contribute significantly to tumor progression, recurrence, drug resistance and metastasis (Jordan et al., 2006). Clarifying the mechanisms regulating breast CSCs has important implications for our understanding of breast cancer progression and therapeutics. There is increasing evidence that a strong connection exists between breast CSCs and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Mani et al., 2008; Morel et al., 2008; Sarrio et al., 2008; Hennessy et al., 2009). Also, the maintenance of the breast CSC phenotype is related to epigenetic and metabolic mechanisms. In this review, we focus on recent studies on the connection between EMT and CSC, and advances made in our understanding of the roles and mechanisms of epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming in controlling breast CSC properties.

2. CSC hypothesis and breast CSCs

According to the CSC hypothesis, a tumor is organized as a hierarchy, in which a small subset of CSCs resides at the apex, and terminally differentiated cells lie at the bottom. This hierarchy contributes to the formation of the heterogeneous bulk of the tumor. On the one hand, CSCs can sustain their ‘stemness’ by symmetrical self-renewal. On the other hand, they can generate lineage-committed progenitor and differentiated cells by asymmetrical division (Wicha et al., 2006).

Al-Hajj et al. (2003) first discovered the existence of CSCs in human breast cancer. Cells with an ESA+/CD44+/CD24−/low/lineage− phenotype were isolated from primary breast cancers using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). This phenotype was more tumorigenic than the CD44+/CD24+ cell population. Indeed, only 200 cells with this phenotype were able to generate tumors consistently after transplantation into the mammary fat pads of non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice, whereas as many as 20 000 CD44+/CD24+ cells failed to form tumors. Subsequently, Ginestier et al. (2007) identified that as few as 20 cells with a CD44high/CD24low/ALDHhigh profile were able to form tumors.

Organ-specific stem cells have the capacity for self-renewal and differentiation into the cell types that comprise each organ (Dontu et al., 2003). It is now becoming evident that CSCs can generate different subtypes of breast cancer cells due to limited or aberrant differentiation (Proia et al., 2011; Driessens et al., 2012; Gerhard et al., 2012; Keller et al., 2012). Breast cancer has been divided into six distinct subtypes based on gene expression profiling: the luminal A, luminal B, basal-like, claudin-low, HER2/ERBB2-overexpressing, and normal-breast-like subtypes. The differences in tumor subtypes are hypothesized to reflect differences in the cell of origin (Perou et al., 2000). Basal-B/claudin-low and metaplastic cancers are suggested to originate from primitive basal mammary stem cells, whereas luminal and basal-like tumors may be generated from luminal progenitors. Indeed, Proia et al. (2011) have found that luminal progenitors are the cells of origin for basal-like breast cancers with BRCA1 and TP53 mutations. Consistent with this notion, luminal progenitor cells induced by oncogenes can give rise to luminal, basal-like, and possibly HER2 subtypes of breast cancers (Driessens et al., 2012; Gerhard et al., 2012; Keller et al., 2012).

3. EMT and CSCs

EMT is an essential process for morphogenetic events in embryonic development, tissue remodeling, wound healing and metastasis, which enables polarized epithelial cells to acquire a motile mesenchymal phenotype (Polyak and Weinberg, 2009; Thiery et al., 2009). Loss of E-cadherin expression as an important hallmark of EMT has been correlated with increased metastasis in several tumor types, whereas re-expression of E-cadherin inhibits tumor cell invasion and metastasis (Polyak and Weinberg, 2009; Thiery et al., 2009). EMT is required for the first step of the tumor metastasis cascade, as differentiated epithelial cells are not capable of migration and invasion. However, cells with a mesenchymal phenotype cannot develop macrometastasis due to their weak capability for adhesion and proliferation. These cells can be regulated by the reversion of EMT, a process termed mesenchymal to epithelial transition (MET), to colonize new sites and create secondary tumors in distant organs (Nieto, 2011). Thus, EMT is a dynamic and reversible process, which switches between on and off states during the metastasis process.

Breast CSCs can interconvert between a stem cell and a non-stem cell state due to their plasticity. Meyer et al. (2009) first reported that non-stem cells (CD44+/CD24+) were able to generate CD44+/CD24− breast CSCs with tumorigenic properties in breast cancer cell lines and vice versa. Subsequent studies found that breast CSCs could differentiate into other cell phenotypes, whereas luminal and basal cells could give rise to a similar proportion of breast CSCs (Gupta et al., 2011). Therefore, a shift between a stem cell and a non-stem cell state can occur in specific conditions. This shift is quite similar to the previously described cancer cell plasticity when undergoing EMT or MET. Indeed, growing evidence has demonstrated that EMT can be induced in human mammary epithelial cells either by treatment with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) or by ectopic expression of Snail or Twist, leading to the acquisition of the CD44+/CD24−/low profile, as well as significantly increased mammosphere formation (Mani et al., 2008; Morel et al., 2008; Sarrio et al., 2008; Hennessy et al., 2009). These results indicate that EMT confers stem cell-like properties on tumor cells, thus making them more tumorigenic and invasive. Interestingly, breast CSCs with a CD44+/CD24−/low phenotype also exhibit EMT traits, such as reduced expression of E-cadherin and increased expression of vimentin, fibronectin, and EMT inducers (Snail, Slug, and Twist) (Fillmore and Kuperwasser, 2007; Blick et al., 2010). These findings suggest that CSC and EMT may share similar regulatory mechanisms due to their tight interconnections.

4. Epigenetic regulation of breast CSCs

Stem cells are linked to a high degree of plasticity, which is required for cell renewal and differentiation. This plasticity is able to be maintained by reversible epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA modulation (Shah and Allegrucci, 2012). This epigenetic regulation affects gene expression without changing the DNA sequence. Epigenetic modifications also are known to contribute to different stages of tumor development, including initiation, invasion, and metastasis, by controlling CSC plasticity (Allegrucci et al., 2007).

Epigenetic modifications are known to regulate transcriptional plasticity and are important for gene activation and repression during stem/progenitor differentiation. Histone modification is an epigenetic mechanism important for chromatin remodeling. The histone amino-terminals are frequently subject to post-translational modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination. Among these modifications, acetylation and methylation are considered as potential marks for carrying epigenetic information through cell divisions and conferring unique transcriptional potential (Barski et al., 2007; Campos and Reinberg, 2009). The most well characterized modifications are the methylations of the Lys9 and Lys27 residues of histone H3 (H3K9me2/3 and H3K27me3), which represses gene expression, and H3K4me3 and H3K9 acetylation (H3K9ac), which is associated with gene activation (Shi, 2007). Over-expression of some epigenetic modifiers has been found to induce breast CSC plasticity. For example, the polycomb protein EZH2 has been observed to over-express in high-grade breast cancers, and plays a fundamental role in controlling stem cell self-renewal and differentiation (Bracken et al., 2006; Holm et al., 2012). In addition, high expression of SUZ12, a member of the polycomb-repressor complex 2, is known to regulate the transcription of genes essential for maintaining the pluripotency and self-renewal of stem/progenitor cells (Lee et al., 2006; Pasini et al., 2007). DNA methylation has been shown to control gene expression by transcriptional repression and formation of heterochromatin during development, differentiation, and carcinogenesis (McCabe et al., 2009). Epigenetic silencing of genes important for pluripotency and self-renewal by promoter methylation is an essential step in mammary epithelial differentiation. We have mentioned above that CD44+/CD24−/low cells display stem/progenitor characteristics and undergo lineage-specific differentiation (Al-Hajj et al., 2003). Interestingly, genes related to cellular stemness were hypomethylated and highly expressed in CD44+/CD24−/low cells compared with the three other differentiated cell types. For example, hypermethylation at the promoters of SUZ12 gene targets was observed in CD24+ cells, but not in CD44+/CD24−/low cells, indicating that acquired DNA methylation may result in permanent silencing of SUZ12 targets during mammary epithelial differentiation (Bloushtain-Qimron et al., 2008). The key roles played by miRNAs in the proper maintenance of CSCs have been revealed recently (Mallick et al., 2011). Regulation of miRNA expression might induce the transformation of a lineage-restricted cell into a CSC (Greene et al., 2010). Recent studies have shown the critical role of miRNA in the breast CSC phenotype (Yu et al., 2007; Shimono et al., 2009; Wellner et al., 2009). The silencing of let-7 contributes to the maintenance of the self-renewal capacity and undifferentiated status in both normal cells and CSCs of the breast (Yu et al., 2007). Another example is miR-200, which can inhibit expression of BMI1 (a known self-renewal regulator) by binding to the 3' UTR of BMI1 (Shimono et al., 2009). In addition, miR-200 as a stemness-inhibiting miRNA can be repressed by the EMT activator ZEB1 (Wellner et al., 2009). Consistent with this notion, the epigenetic silencing of miR-200 was observed in breast CSCs (Yu et al., 2007). Together, the flexibility of these epigenetic modifications provides a rapid switch for regulating gene expression during the differentiation process, while retaining cellular plasticity in response to developmental and microenvironmental signals.

The cellular plasticity of CSCs is determined by the EMT program and can be memorized and passed on to daughter cells by epigenetic modifications (Reik, 2007; Campos and Reinberg, 2009; Cedar and Bergman, 2009). Histone lysine methylation plays vital roles in regulating gene expression and chromatin organization. H3K9 methylation is a well-conserved epigenetic mark for heterochromatin formation and transcriptional silencing. Methylation of H3K9 occurs in euchromatin, which requires mono- and dimethylation (H3K9me1 and H3K9me2) mostly by G9a, and in heterochromatin, which involves trimethylation (H3K9me3) mainly by Suv39H1/2 (Grewal and Jia, 2007; Mohn and Schubeler, 2009). The chromatin structure can be regulated by the histone code that can be written by epigenetic enzymes and read by transcription factors or various binding proteins. Snail, as a transcription factor and EMT inducer, contains DNA-binding domain zinc-finger motifs and can bind to a specific DNA motif (E-box sequence) on the promoter of E-cadherin. Using an unbiased protein affinity purification-mass spectrometry coupled technology, we have identified some Snail-binding chromatin modifying enzymes in cells stably expressing human Snail (Lin et al., 2010). We screened several interesting candidates among these enzymes, including G9a and Suv39H1. Our study found that Snail interacted with G9a both in vitro and in vivo and was required for the enrichment of G9a and the corresponding H3K9me2 at the E-cadherin promoter. DNA methylation is mediated by a family of highly related DNA methyltransferase enzymes (DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b) and commonly occurs in the promoter region of genes (Cedar and Bergman, 2009; McCabe et al., 2009). According to our study, Snail also can interact with DNMT1, DNMT3a and DNMT3b, and is responsible for DNA methylation on the promoter of E-cadherin. Our studies also clearly demonstrated that abolishing Snail-mediated epigenetic regulation led to re-expression of E-cadherin and the reversal of EMT. This suggests that these epigenetic enzymes are able to be recruited to the E-cadherin promoter by Snail to cooperatively cause transcriptional silencing of E-cadherin, thereby becoming involved in the EMT process (Dong et al., 2012). We also investigated another screened Snail-binding protein, Suv39H1. The interaction of Suv39H1 with Snail was critical for the enrichment of H3K9me3 on the E-cadherin promoter in breast cancer cells, and knockdown of Suv39H1 re-activated E-cadherin expression, suggesting a critical role for Suv39H1 in the induction of EMT (Dong et al., 2013a). Furthermore, we identified that knockdown of Snail, G9a and Suv39H1 expression suppressed cell migration and invasion in vitro and inhibited metastasis in vivo (Dong et al., 2012; 2013a), indicating the critical role of Snail-mediated epigenetic regulation in inducing EMT and sustaining the phenotype of breast CSCs.

5. Metabolic reprogramming in breast CSCs

Somatic cells rely primarily on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) for their energy production, whereas pluripotent cells mainly use glycolysis (Facucho-Oliveira and St. John, 2009; Armstrong et al., 2010; Prigione et al., 2010). Using an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) as a model in stem cell reprogramming, both glucose uptake and lactate production were higher in iPSCs than in their parental fibroblasts, whereas oxygen consumption was lower. Metaboproteome analysis also revealed that iPSCs had elevated levels of glycolytic enzymes and decreased levels of electron transport chains compared with their parental fibroblasts. Stimulating glycolysis by elevating media glucose levels increased reprogramming efficiency, whereas inhibition of glycolysis reduced reprogramming (Zhu et al., 2010; Folmes et al., 2011). These findings suggest that the process of reprogramming is associated with a major bioenergetic restructuring to facilitate a conversion from somatic mitochondrial oxidation to a glycolysis-dependent pluripotent state. Our recent study has shown that metabolic reprogramming contributes to the acquisition of CSC properties in breast cancer cells (Dong et al., 2013b). Loss of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP1), a rate-limiting enzyme in gluconeogenesis, which catalyzes the splitting of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (F-1,6-BP) into fructose 6-phosphate and inorganic phosphate, results in a metabolic switch from OXPHOS to aerobic glycolysis in breast cancer cells. Interestingly, loss of FBP1 by Snail-mediated repression is critical for the maintenance of breast CSCs. Indeed, expression of FBP1 in MDA-MB231 and MDA-MB435 cells dramatically reduces the percentage of ESA+/CD44+/CD24−/low population and mammosphere formation, whereas knockdown of FBP1 leads to a remarkable increase in the proportion of the population with a CSC phenotype in luminal MCF7 cells. Together, these results indicate that the glycolytic switch due to the loss of FBP1 expression favors the reprogramming of stem cell-like characters in breast cancer.

In the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment, protection from oxidative stresses, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and superoxide, generated mainly by OXPHOS, is critical for the maintenance of self-renewal (Tothova et al., 2007). Similar to HSCs, human and mouse breast CSCs maintain low levels of ROS (Diehn et al., 2009). These intriguing findings indicate that the self-renewal potential of CSCs in different tissues may be sensitive to levels of ROS, and that the glycolytic switch reduces ROS and facilitates the maintenance of the pluripotent state in CSCs. In our study, loss of FBP1 by Snail-mediated repression could decrease mitochondrial ROS by increasing aerobic glycolysis and suppressing oxygen consumption (Dong et al., 2013b). ROS can mediate the regulation of the Wnt pathway. The Wnt pathway, which modulates the expression of specific target genes through β-catenin, is a critical regulator of stem cells and CSCs (Clevers, 2006). β-Catenin exists in two transcriptional complexes (Bowerman, 2005): (1) β-catenin promotes cell proliferation and stem cell-like properties through its binding with TCF transcription factors; and (2) β-catenin interacts with FOXO to favor the exit from the cell cycle and entry into quiescence. A low level of ROS activates Wnt signaling and favors the interaction of β-catenin with TCF instead of FOXO. Essers et al. (2005) identified that the reduced ROS mediated by loss of FBP1 shifted the interaction of β-catenin towards TCF4 instead of FOXO3a, leading to the activation of the Wnt signaling pathway. Snail-mediated metabolic regulation of EMT may be another important reason for the acquisition of CSC properties in breast cancer. Our study found that ectopic FBP1 expression inhibited morphological changes indicative of EMT, indicating the importance of FBP1 for this event (Dong et al., 2013b). These findings are in line with the notion that expression of FBP1 suppresses CSC phenotypes and tumorigenicity. Clinically, loss of FBP1 is linked to poor patient survival. Clearly, metabolic reprogramming by loss of FBP1 not only changes the metabolic phenotype, but also contributes significantly to the increased CSC phenotypes that are associated with the clinically aggressive behavior of breast cancer.

6. Concluding remarks

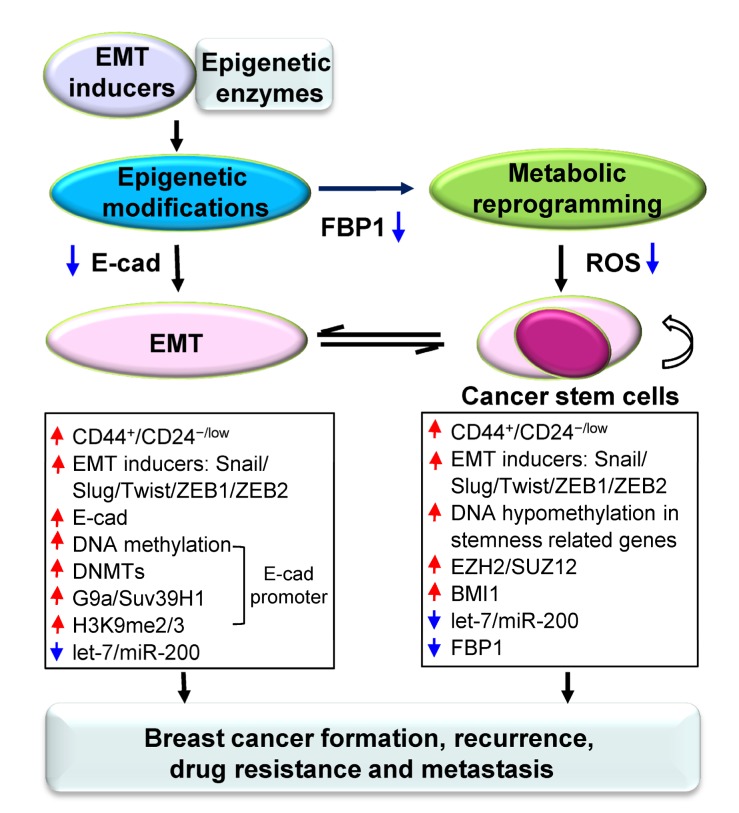

Here, we have reviewed the interconnections between CSCs and EMT, and summarized the key roles and mechanisms of epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming in EMT and breast CSCs. The epigenetic and metabolic program in EMT and CSCs is a complicated transcriptional and regulatory network, which reversibly controls the plasticity of EMT and breast CSCs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the crosstalk among epigenetic regulation, metabolic reprogramming, EMT, and CSCs

Breast CSCs contribute to tumor growth and metastasis and are resistant to conventional therapies, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Theoretically, removing CSCs will stop new tumor growth. Thus, careful assessment of breast CACs and their regulatory networks is needed to devise targeted therapeutic strategies. The plasticity of EMT provides an intriguing mechanism for understanding tumor progression and metastasis, as it allows cancer cells to reversibly transition between epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes, as well as between stemness and differentiation. Blocking EMT may decrease the invasive ability of cancer cells and increase their sensitivity to traditional therapies. However, the metastatic cells participate in the establishment and stabilization of distant metastases by reversing EMT and regaining epithelial properties. In this regard, simply blocking EMT may not efficiently prevent the cancer metastasis. Thus, more information about the regulatory network of EMT needs to be explored before targeting EMT can become a successful method in managing breast cancer. Epigenetic changes may represent a vulnerable point in the self-defense mechanisms of cancer cells, as epigenetic silencing of tumor-suppressor genes can be reactivated with the right inhibitors. In fact, 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine, a hypomethylating agent, has been used as a drug for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Thus, identifying inhibitors that act specifically on DNMTs, G9a and/or Suv39H1 may hold a great promise for breast cancer therapy. Interfering with stem cell self-renewal not only is the strategy of choice, but also presents a great challenge because many regulatory mechanisms are shared by CSCs and their normal counterparts. Based on the metabolic difference between breast CSCs and normal cells, elucidating how metabolic reprogramming is involved in maintaining breast CSC properties will provide new strategies for breast cancer treatment. Further clarification of the mechanisms regulating breast CSCs has important implications not only for our understanding of breast cancer, but also for the development of cancer therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to colleagues whose work was not cited here due to our oversight.

Footnotes

Project supported by the Thousand Young Talents Program of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81472455), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Hui-xin LIU, Xiao-li LI, and Chen-fang DONG declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. PNAS. 2003;100(7):3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allegrucci C, Wu YZ, Thurston A, et al. Restriction landmark genome scanning identifies culture-induced DNA methylation instability in the human embryonic stem cell epigenome. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(10):1253–1268. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almendro V, Fuster G. Heterogeneity of breast cancer: etiology and clinical relevance. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13(11):767–773. doi: 10.1007/s12094-011-0731-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong L, Tilgner K, Saretzki G, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell lines show stress defense mechanisms and mitochondrial regulation similar to those of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28(4):661–673. doi: 10.1002/stem.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129(4):823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blick T, Hugo H, Widodo E, et al. Epithelial mesenchymal transition traits in human breast cancer cell lines parallel the CD44hi/CD24lo/− stem cell phenotype in human breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15(2):235–252. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9175-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloushtain-Qimron N, Yao J, Snyder EL, et al. Cell type-specific DNA methylation patterns in the human breast. PNAS. 2008;105(37):14076–14081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805206105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowerman B. Cell biology. Oxidative stress and cancer: a β-catenin convergence. Science. 2005;308(5725):1119–1120. doi: 10.1126/science.1113356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bracken AP, Dietrich N, Pasini D, et al. Genome-wide mapping of Polycomb target genes unravels their roles in cell fate transitions. Genes Dev. 2006;20(9):1123–1136. doi: 10.1101/gad.381706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campos EI, Reinberg D. Histones: annotating chromatin. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43(1):559–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.032608.103928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cedar H, Bergman Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(5):295–304. doi: 10.1038/nrg2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127(3):469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diehn M, Cho RW, Lobo NA, et al. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature. 2009;458(7239):780–783. doi: 10.1038/nature07733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong C, Wu Y, Yao J, et al. G9a interacts with Snail and is critical for Snail-mediated E-cadherin repression in human breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(4):1469–1486. doi: 10.1172/JCI57349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong C, Wu Y, Yao J, et al. Interaction with Suv39H1 is critical for Snail-mediated E-cadherin repression in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2013;32(11):1351–1362. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong C, Yuan T, Wu Y, et al. Loss of FBP1 by Snail-mediated repression provides metabolic advantages in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(3):316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17(10):1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Driessens G, Beck B, Caauwe A, et al. Defining the mode of tumour growth by clonal analysis. Nature. 2012;488(7412):527–530. doi: 10.1038/nature11344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Essers MA, de Vries-Smits LM, Barker N, et al. Functional interaction between β-catenin and FOXO in oxidative stress signaling. Science. 2005;308(5725):1181–1184. doi: 10.1126/science.1109083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Facucho-Oliveira JM, St. John JC. The relationship between pluripotency and mitochondrial DNA proliferation during early embryo development and embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2009;5(2):140–158. doi: 10.1007/s12015-009-9058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fillmore C, Kuperwasser C. Human breast cancer stem cell markers CD44 and CD24: enriching for cells with functional properties in mice or in man. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9(3):303. doi: 10.1186/bcr1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folmes CD, Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, et al. Somatic oxidative bioenergetics transitions into pluripotency-dependent glycolysis to facilitate nuclear reprogramming. Cell Metab. 2011;14(2):264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerhard R, Ricardo S, Albergaria A, et al. Immunohistochemical features of claudin-low intrinsic subtype in metaplastic breast carcinomas. Breast. 2012;21(3):354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(5):555–567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene SB, Herschkowitz JI, Rosen JM. Small players with big roles: microRNAs as targets to inhibit breast cancer progression. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11(9):1059–1073. doi: 10.2174/138945010792006762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grewal SI, Jia S. Heterochromatin revisited. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(1):35–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta PB, Fillmore CM, Jiang G, et al. Stochastic state transitions give rise to phenotypic equilibrium in populations of cancer cells. Cell. 2011;146(4):633–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Stemke-Hale K, et al. Characterization of a naturally occurring breast cancer subset enriched in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and stem cell characteristics. Cancer Res. 2009;69(10):4116–4124. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holm K, Grabau D, Lovgren K, et al. Global H3K27 trimethylation and EZH2 abundance in breast tumor subtypes. Mol Oncol. 2012;6(5):494–506. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(12):1253–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keller PJ, Arendt LM, Skibinski A, et al. Defining the cellular precursors to human breast cancer. PNAS. 2012;109(8):2772–2777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017626108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee TI, Jenner RG, Boyer LA, et al. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125(2):301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin Y, Wu Y, Li J, et al. The SNAG domain of Snail1 functions as a molecular hook for recruiting lysine-specific demethylase 1. EMBO J. 2010;29(11):1803–1816. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mallick B, Chakrabarti J, Ghosh Z. MicroRNA reins in embryonic and cancer stem cells. RNA Biol. 2011;8(3):415–426. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.3.14497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133(4):704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCabe MT, Brandes JC, Vertino PM. Cancer DNA methylation: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(12):3927–3937. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer MJ, Fleming JM, Ali MA, et al. Dynamic regulation of CD24 and the invasive, CD44posCD24neg phenotype in breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(6):R82. doi: 10.1186/bcr2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohn F, Schubeler D. Genetics and epigenetics: stability and plasticity during cellular differentiation. Trends Genet. 2009;25(3):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morel AP, Lievre M, Thomas C, et al. Generation of breast cancer stem cells through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e2888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nieto MA. The ins and outs of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition in health and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27(1):347–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pasini D, Bracken AP, Hansen JB, et al. The polycomb group protein Suz12 is required for embryonic stem cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(10):3769–3779. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01432-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polyak K. Heterogeneity in breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):3786–3788. doi: 10.1172/JCI60534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(4):265–273. doi: 10.1038/nrc2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prigione A, Fauler B, Lurz R, et al. The senescence-related mitochondrial/oxidative stress pathway is repressed in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28(4):721–733. doi: 10.1002/stem.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Proia TA, Keller PJ, Gupta PB, et al. Genetic predisposition directs breast cancer phenotype by dictating progenitor cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(2):149–163. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reik W. Stability and flexibility of epigenetic gene regulation in mammalian development. Nature. 2007;447(7143):425–432. doi: 10.1038/nature05918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarrio D, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Hardisson D, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer relates to the basal-like phenotype. Cancer Res. 2008;68(4):989–997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shah M, Allegrucci C. Keeping an open mind: highlights and controversies of the breast cancer stem cell theory. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2012;4:155–166. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S26434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi Y. Histone lysine demethylases: emerging roles in development, physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(11):829–833. doi: 10.1038/nrg2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimono Y, Zabala M, Cho RW, et al. Downregulation of miRNA-200c links breast cancer stem cells with normal stem cells. Cell. 2009;138(3):592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139(5):871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tothova Z, Kollipara R, Huntly BJ, et al. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell. 2007;128(2):325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wellner U, Schubert J, Burk UC, et al. The EMT-activator ZEB1 promotes tumorigenicity by repressing stemness-inhibiting microRNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(12):1487–1495. doi: 10.1038/ncb1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wicha MS, Liu S, Dontu G. Cancer stem cells: an old idea—a paradigm shift. Cancer Res. 2006;66(4):1883–1890. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3153. discussion 1895-1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu F, Yao H, Zhu P, et al. let-7 regulates self renewal and tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2007;131(6):1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu S, Li W, Zhou H, et al. Reprogramming of human primary somatic cells by OCT4 and chemical compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(6):651–655. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]