Abstract

Former prisoners are at high risk of economic insecurity due to the challenges they face in finding employment and to the difficulties of securing and maintaining public assistance while incarcerated. This study examines the processes through which former prisoners attain economic security, examining how they meet basic material needs and achieve upward mobility over time. It draws on unique qualitative data from in-depth, unstructured interviews with a sample of former prisoners followed over a two to three year period to assess how subjects draw upon a combination of employment, social supports, and public benefits to make ends meet. Findings reveal considerable struggle among our subjects to meet even minimal needs for shelter and food, although economic security and stability could be attained when employment or public benefits were coupled with familial social support. Sustained economic security was rarely achieved absent either strong social support or access to long-term public benefits. However, a select few were able to leverage material support and social networks into trajectories of upward mobility and economic independence. Policy implications are discussed.

In 1975 the population in jails and prisons on any given day was roughly 400,000 people. By 2003 this number had increased more than fivefold to 2.1 million people (Western, 2006). Although the upward trend in incarceration has begun to level off in the last few years, the number of individuals in state and federal prisons was over 1.6 million at the end of 2009 (Freudenberg et al., 2005). Compared to other nations and earlier periods in US history, current incarceration rates are unprecedented (Raphael, 2011; Western, 2006), leading to what some have termed the era of mass imprisonment (Garland, 2001; Mauer & Chesney-Lind, 2002). Because almost all prisoners are eventually released, mass incarceration has in turn produced a steep rise in the number of individuals reentering society and undergoing the process of social and economic reintegration (Travis, 2005). Over 700,000 individuals are now released from state and federal prisons each year (West, Sabol, & Greenman, 2010). In addition, the prison boom was accompanied by an even larger boom in the number of people under community supervision, with a recent study finding that one in every 48 American adults are either on probation or parole on any given day (Glaze & Bonczar, 2011).

The large number of individuals exiting prison each year has prompted renewed interest among academics and policy makers in the challenges of reintegrating former prisoners into society (Visher & Travis, 2003), especially as some states have begun to release more prisoners into the community in an effort to cut costs by reducing the size of prison populations (Wool & Stemen, 2004). The challenges appear daunting, as the prospects for successful reentry are often dim. More than 40% of those released return to prison within three years, a phenomenon known as the “revolving door” (Pew Center on the States, 2011).

Much of the focus of the scholarship and policies addressing prisoner reentry has understandably focused on recidivism. However, desisting from crime is just one component of successful offender reintegration. Another key determinant of whether returning prisoners are able to establish conventional lifestyles is meeting basic material needs (Travis, 2004). Barriers returning prisoners face to finding stable sources of employment, public assistance, and social support (Holzer, Raphael, & Stoll, 2004, 2007; Pager, 2003, 2007; Pager, Western, & Bonikowski, 2009) as well as the disadvantages that characterize this population, including low levels of human capital and a high prevalence of mental health problems and substance use (Visher & Travis, 2003), all make economic stability and security a significant challenge. Few prisoners leave prison with jobs, assets, or other resources waiting for them in the community (Travis, 2005), and being unemployed is a risk factor for criminal behavior (Hagan, 1993; Tanner, Davies, & O’Grady, 1999; Uggen, 2000).

The economic insecurity of returning prisoners also poses a challenge for social welfare policymakers, as access to and effective use of public and non-profit social services are potentially critical for this population. In addition, programs and policies at all levels of government already play an important role in their lives, including community supervision, health care, public benefits, public transportation, and social services. As a result, policymakers may have considerable opportunity to intervene in ways that improve their wellbeing. In particular, community supervision programs such as parole involve frequent contacts with state systems that could be leveraged to improve access to services and supports.

Despite the large number of economically vulnerable individuals returning to communities each year, we know surprisingly little about how former prisoners make ends meet after their release from prison, how or why some are able to secure services and supports while others are not, or which services and supports create pathways to long term stability and economic independence. Although there have been landmark studies of the survival strategies of other vulnerable populations, such as low-income single mothers with children (Edin & Lein, 1997) or poor urban households more generally (Stack, 1975), few prior studies address such strategies among contemporary former prisoners.1

A primary reason for these gaps in our knowledge is that this population is difficult to study. Current and former prisoners are often absent from large scale surveys, as the institutionalized population is usually excluded from the sampling frame of social science datasets, and those involved in the criminal justice system are thought to be loosely attached to households, which typically form the basis for sampling. Moreover, this population is difficult to recruit while under community supervision or in custody without the assistance of criminal justice authorities and difficult to follow over time due to high rates of residential mobility. For example, one recent survey of 400 former prisoners in Illinois lost approximately half of its respondents to attrition after only two years of follow-up (La Vigne & Parthasarathy, 2005).

The present research draws on unique qualitative longitudinal data from in-depth, unstructured interviews with a sample of former prisoners followed over a two to three year period, beginning just prior to their release from prison. We use these data to uncover the processes through which our subjects do or do not attain some measure of economic security and independence following their release. We examine how they develop stable resources to meet their basic material needs for shelter and food and how they achieve upward mobility. More specifically, we ask the following questions: How do former prisoners gain access to social support, social services, and employment? Which forms of support and services help facilitate long-term employment or other permanent sources of income in this population? And how do former prisoners achieve economic stability and upward mobility over time?

Our findings offer a sobering portrait of the challenges of meeting even one’s basic needs for food and shelter after prison, as many subjects struggled mightily while navigating the labor market with a felony record and low human capital, attempting to stay away from drugs and alcohol, and re-establishing social ties. At the same time, our results reveal how some of the former prisoners in our study managed to attain some level of economic security and stability by combining employment, public benefits, social services, and social supports. We explain why employment was a necessary but not sufficient condition for long-term economic security, which required other forms of material support as well, either from social ties to family or romantic partners or access to long-term public benefits like SSI and housing assistance. While some subjects achieved economic stability, only a select few were able to leverage material support and social networks from family and partners into a trajectory of upward mobility and economic independence. Policy implications of these findings are discussed in the conclusion.

Prisoner Reentry and Reintegration

Although once overshadowed by debates over sentencing policies and rising rates of imprisonment, the challenge of reintegrating returning prisoners was brought to light by scholars such as Joan Petersilia (2009) and Jeremy Travis (2005), who also introduced a distinction between two complementary perspectives on prisoner reentry (Travis, 2004). The “reentry” perspective focuses on reducing recidivism after release by preparing inmates for reentry through programming, such as substance use treatment and job readiness. The “reintegration perspective” focuses on social and economic reintegration after release. This perspective emphasizes entering the labor market and repairing and renewing ties to family and community. A third perspective, discussed further below, focuses on the consequences of mass incarceration for prisoners’ families and communities.

Most scholarship on former prisoners focuses on recidivism and desistance from crime, much of it guided by theories of social control, particularly how social control changes over a person’s life course (Laub & Sampson, 2003; Sampson & Laub, 1992, 1993; Shover, 1996). This framework emphasizes the importance of social bonds – particularly those resulting from marriage, employment, and military service – in deterring criminality and encouraging desistance (Laub, Nagin, & Sampson, 1998; Laub & Sampson, 2003; Sampson, Laub, & Wimer, 2006). These bonds can be strengthened by key life events, so-called “turning points” that potentially increase social control, by altering daily routines and stabilizing pro-social roles. Moreover, former offenders who experience such changes in their social roles and relationships may also adopt new identities or self-concepts (Maruna, 2001). Thus, due to the role of employment and social relationships in desistance, desistance from crime is intimately tied to social and economic reintegration, linking the reentry and reintegration perspectives.

However, many of the sources of social bonds emphasized in prior research, such as marriage, the military, and steady employment, are not available to contemporary returning prisoners – even those motivated to desist – as job opportunities are scarce for ex-offenders, military service is closed to most convicted felons, and marriage is rare in this subpopulation (Greenfeld & Snell, 1999; Western, 2006). Thus, renewed study of the post-prison experiences of ex-offenders and their interactions with a wider set of social relationships, sources of income, and institutions is required to understand the contemporary experience of prisoner reentry and reintegration. Leverentz (2011; 2006) shows that former prisoners draw heavily on social identities and relationships with family of origin and mostly non-marital romantic partners to facilitate desistance, based on interviews with 49 female, mostly African-American ex-offenders from a halfway house in Chicago followed for a year after release. For these women, such relationships play both positive and negative roles in desistance, substance use, and material wellbeing.

A growing body of scholarship with important implications for prisoner reintegration has documented the impact of mass incarceration on the communities and families on which former prisoners rely. (Mauer & Chesney-Lind, 2002; Pattillo, Weiman, & Western, 2004; Travis & Waul, 2003). This literature shows that incarceration of a family member increases household material stress, increases the risk of foster care placement, leads to behavioral and schooling problems in children, and impacts both mental and physical health (Braman, 2004; Comfort, 2008; Johnson & Waldfogel, 2004; Lee et al., 2013; Wildeman & Muller, 2012). Reincorporating a formerly-incarcerated family member into the household may exacerbate some of these problems, especially in the short term (Braman, 2004). These findings suggest that former prisoners may have difficulties securing social support upon release, particularly those former prisoners from already disadvantaged families and communities.

Barriers to Economic Stability and Mobility Among Former Prisoners

Former prisoners face considerable barriers to attaining economic stability and integration. One important set of barriers includes legal and policy restrictions on former offenders. Many states have banned those with felony convictions from benefits such as food stamps, TANF, SSI and residence in public housing, either permanently or temporarily (Freudenberg, et al., 2005; Godsoe, 1998; Pinard, 2010; Rubinstein & Mukamal, 2002; Travis, 2005). Rules that bar those with a felony record from public and subsidized housing may limit residence with friends and family as well, and increase the likelihood of homelessness (Travis, 2005). Offenders who had been receiving state and federal income support often face the loss of these benefits during incarceration, some of which can cease once a person has been incarcerated for 30 days or longer (Brucker, 2006), and reinstating benefits following a period of incarceration can be challenging.2 Notably, restrictions on many public benefits apply largely to drug offenders. Because drug-related offenses constitute the majority of crimes committed by women, it is likely that female offenders are disproportionately impacted by these restrictions (Brown, 2000).3 Returning prisoners also face mounting financial pressure from an accumulation of debts and fees (Harris, Evans, & Beckett, 2010; Wakefield & Uggen, 2010), particularly for child support (Cancian, Meyer, & Han, 2011). Although barriers to obtaining public benefits have been well documented, prior research has shed little light on how some ex-offenders secure benefits, which benefits they tend to be, and their role in achieving economic security.

Although an important potential pathway towards economic independence is establishing employment, here former prisoners also face considerable barriers, in part because having a felony record excludes them from some occupations entirely, and also because employers’ unwillingness to hire people with a felony record reduces their chance of securing any job (Holzer, 2003; Holzer, Raphael, & Stoll, 2006; Mukamal, 1999). Pager (2003, 2007) suggests that a criminal record acts as a negative credential on the job market, signaling a general lack of trustworthiness and employability. Specifically, employers may expect ex-offenders to lack soft skills, clash with other employees, and prove unreliable in the handling of cash and goods (Bushway, Stoll, & Weiman, 2007). Such stigma is intensified for African American men, who face heightened racial stereotypes given a felony record (Pager, 2003, 2007). Yet some offenders are able to secure and maintain employment, and in so doing, facilitate their desistance from crime (National Research Council of the National Academies, 2007).

Low levels of human capital, poor health, and lack of work experience also pose barriers to former offenders’ economic stability and mobility. Forty-one percent of those released from prison lack a high school education, and 73% have a history of drug and alcohol abuse. The already high levels of social, psychological and physical problems that mark this population are exacerbated by periods of imprisonment (Petersilia, 2005). Visher and Travis (2003) identify poor job skills, sporadic work histories and a dearth of conventional social ties and behaviors as factors limiting ex-offenders’ successful reintegration. Incarceration may erode human capital, as skills decline, a gap in the work record is established, diseases and psychological disorders are exacerbated, and behaviors learned for survival in prison conflict with workforce norms (Bushway, Stoll, & Weiman, 2007). Even if employment is established, it may be difficult for ex-offenders to maintain (Pettit & Lyons, 2007; Sabol, 2007; Tyler & Kling, 2007).

Whereas the barriers returning prisoners face to successful labor market integration have been well documented in prior research, less is known about the survival strategies they employ to overcome these barriers. One survey-based study in Baltimore found that ex-offenders relied heavily upon family for housing and financial assistance. Family and other social connections were also leveraged to secure employment (Visher et al., 2004). A linked study additionally found that offenders’ families proved even more helpful than offenders had anticipated while incarcerated (Naser & La Vigne, 2006). In an ethnographic study, Fader (2013) studied the incarceration and reentry experiences of minority male juvenile offenders in Philadelphia, documenting their challenges finding work, navigating high crime neighborhoods, avoiding the temptation to return to drug dealing, and rebuilding relationships with family and romantic partners. As young adults, Fader’s subjects relied heavily on social support from families and romantic partners to meet their basic material needs.

Looking to prior research on other vulnerable populations, studies suggest that reciprocal exchange is critical to day-to-day survival (Stack, 1975). In their qualitative study of how single mothers on welfare make ends meet, Edin and Lein (1997) found that in-kind and cash gifts from family members, children’s fathers, and romantic partners along with under-the-table employment and odd jobs were required to supplement cash welfare and housing subsidies. Yet it remains unclear how former prisoners are able to muster such supports given how little they have to offer in exchange and the possibility of relationship deterioration and weakened social ties during periods of incarceration. Furthermore, securing under-the-table work may not be possible if parole officers require “pay stubs” as evidence of legal employment.

In sum, the barriers posed by institutional and legal restrictions, stigma and low human capital raise a number of questions about how former prisoners make ends meet after prison. Given challenges in finding employment, how are basic material needs for shelter and food met? Which former prisoners are able to meet these needs through social services, public benefits, and support from family and friends rather than by returning to crime? And which short-term solutions lead to more successful reintegration in the longer term? Finally, how are some ex-offenders able to attain economic security and mobility while others are not?

Methodology: Data Collection and Analysis

We take an inductive approach, relying upon qualitative methods as those best suited to uncover diverse and complex social processes. In qualitative interviews, the researcher can begin to reveal the subject’s understanding of his or her experiences, gather data on the details of those experiences, and explore if and how the processes suggested in the literature square with the subject’s experiences and conceptualizations (Lofland & Lofland, 1995). Our data come from in-depth longitudinal qualitative interviews that probe the social, economic, and cultural processes related to prisoner reentry and criminal desistance. The sample of 15 male and seven female interview subjects was selected from Michigan Department of Corrections’ (MDOC) administrative records based on their expected release date (those who would be released within two months of the baseline interview) and release county (four counties in Southeast Michigan).

The authors intentionally chose to study a small number of subjects intensively over a relatively long period of time for three reasons. First, a longitudinal design is necessary in a study of released prisoners due to the rapidly changing nature of their lives. Reentry is a period of significant flux and ex-offenders’ experiences immediately after release may be very different from their experiences months and years later. Second, a longer follow-up allows for the observation of outcomes that take time to develop. Third, frequent interviews are required to capture the processes driving change over time as well as to increase subject retention in this hard to study population (see below on strategies used to prevent subject attrition).

Because statistical representativeness across multiple subject characteristics is impossible in a study with a small sample size, we instead pursued a “purposive” sampling strategy common in qualitative research (Kuzel, 1992). Our goal in selecting subjects was to ensure racial and gender diversity, diversity of local geographic context, and diversity of services and supervision provided by MDOC. Accordingly, the sample was stratified by gender, race (white vs. black), reentry county (urban vs. suburban), and type of release (receiving services from Michigan Prisoner Reentry Initiative [MPRI], not receiving MPRI services, or being released without parole [i.e., “maxing” out]).4 Within these categories, potential subjects available at the time of recruitment were selected at random. This sampling strategy ensures that theoretically important categories are present and therefore that conclusions drawn are not particular to the largest group of former prisoners in the population (minority males released to central cities).5 Three male subjects refused to participate in the study and one female subject was discontinued from the study after she was denied parole after the first in-prison interview. These subjects were replaced by additional randomly selected individuals with the same sampling characteristics, resulting in a response rate for in-prison pre-release interviews of 86% (24/28).

Individuals involved in criminal activity, the criminal justice system, and substance abuse are challenging to study. Although we began the study with pre-release interviews with 24 subjects, two subjects, one male and one female, left the study immediately following their prison release. These subjects were younger than our average subject, and both were subsequently convicted of new crimes. All remaining 22 subjects were interviewed once before release, and were interviewed repeatedly during the two years following their release, with follow-up interviews targeted at approximately 1, 2, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months (see Appendix A for detailed interview timing), for a total of 154 interviews.6 The number of post-release interviews per subject ranged from two (two subjects who were returned to prison not long after release) to eleven, with a mean of 5.8 and median of six.

The first two post-release interviews were targeted for the first and second months after release in order to capture the challenges and instability of the immediate post-release period, when assistance from family, friends, partners, and social services was expected to be most necessary. Following the initial interviews, most subjects followed a fairly regular interview schedule at roughly every three months through the first year and every six months thereafter unless we could not stay on schedule due to incarceration, residential treatment, or absconding.

For some subjects, we intentionally allowed interview timing to vary, depending on their circumstances. In some cases we conducted interviews more frequently when subjects’ lives were particularly unstable. In other cases subjects took up criminal behaviors – using drugs, committing new crimes, and absconding from parole – for a period of months. For these individuals, we were able to complete interviews at a later date that discussed the missed time period, including follow-up interviews in prison with three subjects. For all but one of our subjects who committed new crimes, we were able to interview the subject at some point afterwards. One subject was killed in a shooting during the second year of the study. Another subject achieved economic stability one year after release and, because his material circumstances and sources of income remained unchanged, he did not require further formal interviews, although we kept in touch with him informally throughout the study period and monitored his parole agent’s case notes for criminal infractions as well as residential moves or changes in work and schooling, of which there were none.7

We used a number of strategies to maintain contact with subjects in this difficult to track population. The most important was access to parole agents’ records, which allowed us to maintain contact with subjects whenever parole agents knew how to find them. For all but two subjects, we obtained consent to access their MDOC records, allowing us to view their parole agents’ case notes for updated contact information, substance use tests, parole violations, and arrests. This was particularly useful for tracking residential moves, periods of incarceration in jail, and periods of confinement to residential treatment. A second strategy was to elicit from subjects at the initial interview and regularly thereafter the names and contact information of three individuals who would be likely to know how to get in contact with them. A third strategy was to provide incentive payments of $60 per interview. Finally, we believe, though cannot independently verify, that the rapport we were able to develop with subjects over repeated interviews also contributed to our lower attrition rate than some earlier studies of former prisoners. In total, we were able to maintain regular contact with 19 of 22 subjects across the two-year period, although this involved less frequent interviews with four imprisoned subjects once they were incarcerated, and a truncated interview schedule with the subject who was killed. Three subjects attritted during the course of the study at 2, 12 and 20 months.

In-prison interviews were conducted in private rooms (often those used by lawyers visiting their clients). MDOC regulations forbid recorders within prisons, so field notes were used to document in-prison interviews. Post-release interviews were primarily conducted in the subjects’ residences, but also occasionally in the researchers’ offices or in a public location. These interviews were recorded and transcribed. Interviews covered a diverse array of topics, both researcher and subject driven, but focused on the subject’s community context, family roles and relationships, criminal activities and experiences, life in prison, service use, and health and well-being, including drug and alcohol abuse. Interviews were unstructured, meaning that we prepared a detailed interview protocol with a lengthy list of questions and follow-up probes on the above topics but let the conversation follow the interests and experiences of the subject. When a particular conversation thread was complete and the list of probes exhausted, we returned to the next topic in the protocol. Initial in-prison interviews were roughly 90 minutes, while follow-up interviews usually lasted 1–2 hours. Our research design captures subjects both directly before release, allowing for investigation of subject’s pre-release expectations, and during the first 2–3 years after release, a critical period for desistance (National Research Council of the National Academies, 2007).

Half of the male sample is white and half black.8 At the initial interview, men ranged in age from 22 to 71, with most subjects in their late-twenties to early-thirties. Crimes of which male subjects were convicted range from armed robbery to driving under the influence (multiple convictions can lead to imprisonment) to manslaughter. Five male subjects were being released from prison for the first time; all others had experienced multiple prison spells.9 The female sample is also half white and half black. Women ranged in age from 22 to 52 at the initial interview, with most subjects in their late-thirties or early forties. Women’s crimes ranged from felony firearm possession to retail fraud to drug selling. Three women were leaving prison on their first release; the other four had served previous prison terms. We assigned pseudonyms to all subjects and to any other individuals mentioned by name.

All but four of the 15 men and two of the seven women in our study engaged in some form of illegal behavior other than drug use (including behavior not known to law enforcement authorities) during the study. Drug and alcohol addiction was also common among our sample members, and these issues played an important role in their attempts to secure social supports, their ability to comply with service providers’ expectations, and their capacity to gain and sustain employment. Our interviews made clear that conventional measures of involvement in drugs, such as whether a subject has been convicted of a drug-related crime, understate the prevalence and significance of these addictions. The majority of subjects’ crimes were committed while under the influence of drugs or alcohol or motivated by drugs. Six of our 15 male subjects characterized themselves as alcoholics, five as both drug abusers and alcoholics, three as drug abusers solely, and only one reported no addiction to drugs or alcohol. Of seven female subjects, four characterized themselves as drug addicted, one as drug and alcohol addicted, and one as formerly drug addicted. Only one woman did not describe a serious current or past problem with drugs or alcohol.

Our analysis and results depend on the collection of potentially sensitive data from subjects, so the cultivation of rapport and trust with subjects was critical. Subjects were matched with interviewer on gender. Interviews were conducted by the first, second, and fourth authors. The same interviewer conducted all interviews and interactions with each subject throughout the study. The longitudinal nature of the study was also critical to building rapport and trust, as subjects revealed more and more information as interviews progressed, occasionally including information that was intentionally withheld in earlier interviews. One potential barrier to trust was the recruitment of subjects in prison with the cooperation of MDOC. However, consent forms clearly stated that no individual information from the study would be shared with MDOC or any other law enforcement agency unless there was indication of imminent harm to subjects or others, and we secured a Certificate of Confidentiality prior to the initial interviews in order to protect study data from law enforcement and the courts.

The coding and analysis of the field notes and transcripts was conducted using Atlas TI qualitative software. The authors generated an initial list of codes prior to analysis based on categories and concepts motivated by theory and prior empirical research, and then developed additional codes during the course of the analysis. Coding was done by the second author and four research assistants trained in the meanings of the codes and rules for their application. Research assistant coding was compared to that of the second author until a high degree of agreement occurred. The codes most relevant to this paper were those related to job search and employment, use of public and private social services and informal sources of support from family and friends, as well as barriers to accessing employment, services and supports. Where possible, we cross-checked specific facts with those recorded in parole agent’s case notes.

Our analysis alternated between two parallel forms, a subject-based mode, which considers the details of each case and interconnections between domains, and cross-case mode, which looks for patterns across individuals within domains. Our main goal in using such an approach was to characterize subjects’ trajectories of material wellbeing and economic mobility. We began this analysis by creating a detailed timeline and summary of employment, services and social supports for each subject, paying particular attention to changes over time and to whether and how basic material needs – particularly shelter and food – were being met. These timelines tracked eight categories of information: housing, employment, social support, government support, health problems, illegal activity, education/training, and other (e.g. debt or supervision fees and victim restitution payments). The third author created these timelines and summaries from the coded fieldnotes and transcripts, and the timeline and summary material compiled on each subject were then checked by the author who conducted the interviews (one of the other three authors). To synthesize our observations, we developed a typology characterizing five different “states” along a continuum of material hardship to wellbeing. These states are ideal types that characterize the level of hardship/wellbeing a person was experiencing at a given point in time. In characterizing these states we paid careful attention to material resources secured through criminal activity as well as other involvement in criminal activity and contact with the justice system, as these activities are often inversely related to securing basic material needs through conventional means.

We defined the five states of material hardship/wellbeing among our subjects as follows:

Desperation refers to extreme material need: living on the streets or in abandoned buildings and not having enough food to eat. Few subjects experienced this state of extreme deprivation, and those who did so experienced it for only brief periods of time.

Survival refers to a state in which the individual is “getting by” day to day, but housing and food sources are unstable and insecure. We used this category to characterize periods of time when subjects were relying on soup kitchens or food pantries for meals and/or living in homeless shelters, short-term transitional or temporary housing, residential treatment programs with an impending end date, or private housing that was contingent on public benefits or social support that they were at high risk of losing.

Stability refers to a state in which the individual has secure sources of shelter and food and has reasonable certainty that these needs will continue to be met for the foreseeable future. Examples include subjects who lived with their parents after release with assurances that they could stay there as long as necessary, as well as those who had sufficient income from either employment, or long-term sources of public assistance, such as SSI.

Independence was reserved for individuals who were not only stable but had sufficient resources or prospects for advancement to move beyond a day-to-day existence and toward a more middle-class standard of living. It characterizes final stages in the trajectories of the few subjects who either attended college or secured jobs with prospects for career advancement and improved future income. Individuals in this category had strong stakes in conformity, commitments to conventional norms, and low levels of material stress.

Custody is the only state that cannot be characterized as part of an ordered continuum from hardship to wellbeing. Rather, it characterizes periods of time in which individuals were under custody for either short or long periods and therefore securing shelter and food needs by being in jail, prison, a residential program, or detention center.

We used this typology of states to inductively develop modal “trajectories” of hardship/wellbeing, based on our analysis of how subjects moved in and out of different states over time. We created a spreadsheet that tracked states on a monthly basis and used that to code each subject’s trajectory. Trajectory assignments were made by the third author and then verified by the author who had interviewed the subject. Trajectories are described below in the results section. While identifying and describing typical trajectories requires considerable simplification of complex patterns, the four trajectories we describe broadly capture significant distinctions that demonstrate the larger patterns in our longitudinal data.

Results

We organize our presentation of results as follows. We begin by providing an overview of how subjects combined various sources of material resources to make ends meet over time, briefly describing four trajectories of material wellbeing and fulfillment of basic needs that we observed in our data. Utilizing comparisons across subjects, we then elucidate the key processes that allowed some subjects to move between states and thereby achieve trajectories of sustained economic stability or upward mobility after release from prison (e.g. reconnecting with family or romantic partners to garner social support, securing public benefits, and strategies to overcome the felony stigma in the labor market).

Modal Trajectories of Material Wellbeing

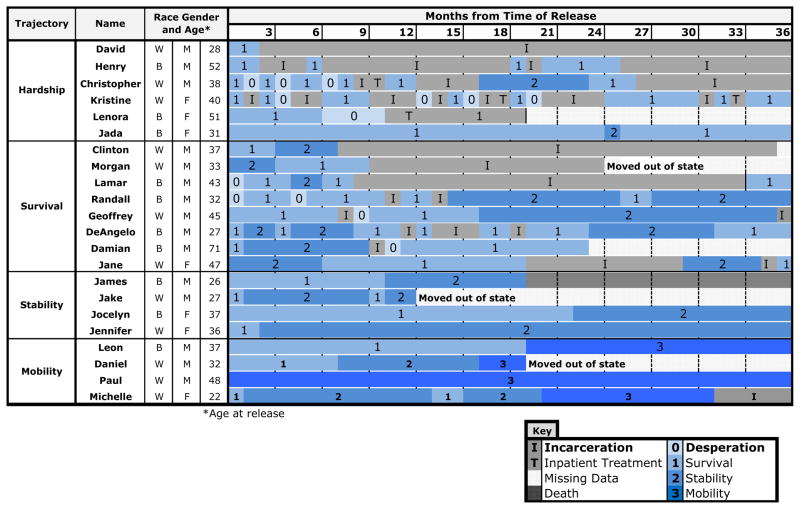

Four trajectories capture the general patterns followed by subjects across the five states of material hardship/wellbeing we identified. These four trajectories are differentiated based on the level of economic security that the former prisoner eventually achieved, the speed with which the subject attained that economic security, and whether that security was maintained over time. We emphasize that many subjects experienced frequent transitions between states of economic security and insecurity, and that the majority of our subjects were not able to sustain long-term stability or achieve mobility. Figure A1 in the appendix provides a graphical representation of each subject’s trajectory.10 It indicates which state each subject was in during each month after release up to 36 months and identifies the overall trajectory assigned to each subject as well as the subject’s race, gender, and age at release. (Although custody and death do not figure directly into our assessment of trajectories, they are also indicated in the figure to aid interpretation.11) Note that both men and women are present in each of the four trajectories, and there are no discernible racial differences in trajectories.

1. Trajectories of Continual Hardship

About one quarter of our subjects (6 out of 22) lived in a continual state of material hardship, transitioning between extreme desperation and survival when they were not in custody. These subjects never established a stable independent living situation. Most but not all of these subjects struggled mightily with substance abuse and addiction. In some cases this prevented them from effectively seeking employment and developing the social ties necessary to secure housing and food through social support, but in other cases, drug or alcohol relapse resulted from initial failures at these goals. This group also tended to maintain substantial involvement with the criminal justice system, facing additional sanctions such as drug treatment, short jail stays, and returns to prison.

2. Trajectories of Survival and Marginal Stability

The most common type of trajectory – experienced by eight subjects – was characterized by a vacillation between periods of stability and survival. Periods of stability were facilitated primarily by employment, family support, or some combination of the two, while periods of crisis were precipitated by family conflict, layoff or job loss, or when crucial supports for maintaining employment, such as transportation assistance, were lost. Downward transitions were often accompanied by addiction relapse or by crimes intended to generate economic resources.

3. Trajectories of Long-Term Stability

Four subjects attained economic stability and managed to maintain it over time, although they experienced no further prospects for economic or material advancement. These subjects tended to receive substantial family support in addition to another source of support like low-wage employment or public benefits. The combination of the two meant that family did not have to be relied upon constantly, which can strain such relationships, but could be accessed on an as-needed basis to maintain one’s gains when benefits were cut off or a job loss occurred. Despite these advantages, upward mobility remained out of reach.

4. Trajectories of Upward Mobility

Finally, four subjects experienced an improvement in material conditions and economic security even after achieving stability, eventually resulting in independence. These individuals returned to families or partners who provided them with substantial support. These were typically middle class families that could offer not only a temporary place to stay and food to eat but long-term shelter and access to other material resources. Often this support was accompanied by job networks that led to higher paying stable employment. Family support also provided “breathing space” to search for the right job or return to school without having to worry about short term material needs. Individual characteristics enabled this trajectory as well, as these subjects had the human capital to take full advantage of such opportunities.

Achieving Stability

How and why did some former prisoners in our study achieve economic stability while others did not? In this section we draw upon comparisons across subjects on different trajectories to understand the sources of this variation. We highlight three primary resources through which economic security was achieved: employment, social supports, and public benefits. However, the examples we discuss below reveal that attaining stability was often contingent upon individual characteristics and access to additional resources as well.

Employment

While the barriers facing former prisoners in the labor market are well known, many of our subjects did find employment, and some were able to translate this employment into a trajectory of long-term economic security.12 All but two of the fifteen male subjects relied on employment as a source of income at some point. Only one male subject began working immediately after release, and this was closely linked to his immediate enrollment in postsecondary education (Paul). Another secured employment two months after release and maintained it throughout the study period (Leon). The rest of the men who were able to secure a job at some point had considerable trouble either attaining or maintaining that employment, or both. Most worked in restaurants and car repair or maintenance shops, though other forms of manual labor and informal employment were also used at times (e.g., plasma donation, collecting cans, cleaning, and caretaking). Two men (Morgan and Geoffrey) had skills that provided higher levels of income (master plumber and car salesman). Both absconded from parole but managed to continue working while in this precarious legal status.

Five of the seven female subject relied on employment as a source of support at some point as well, with only one female subject (Michelle) regularly employed, although she moved frequently between jobs. Two female subjects relied predominantly on SSI, remaining unemployed throughout the study period (Jennifer and Jocelyn). Of the women who did depend on employment at some point, this employment was often short-lived. Female subjects were predominantly employed in restaurants, cleaning positions, and other service sector jobs. One female subject was trained as a nurses’ aid (Jada), but was no longer eligible for this type of employment due to her criminal record. She remained largely unemployed.

Subjects used multiple strategies for finding jobs, and many had trouble maintaining employment. Some found jobs through sheer volume of applications, while others relied on their social networks. Securing and maintaining employment was facilitated by effective presentation of self, regular access to reliable transportation, either public transportation or friends and family able and willing to help with rides, and proximity to jobs in the suburbs. Significantly, sustained economic security could only be achieved via employment when challenging personal circumstances or individual characteristics (e.g., addictions, childcare responsibilities, or transportation problems) did not prove insurmountable.

The importance of employment for initiating a long-term trajectory of economic security is illustrated by the comparison between Michelle and Jada. Both Michelle and Jada are young, high school educated mothers. For both, this period of imprisonment had been their first. However, their experiences securing employment following their incarceration differed dramatically, with significant implications for their economic security. Michelle was easily able to secure relatively lucrative jobs, which allowed her to meet not just her material needs, but pay off debts and set her sights on longer-term goals. Three years after her prison release, Jada, who was never able to land a permanent job, continued to struggle mightily to meet even basic economic needs.

Michelle is a twenty-five year old white woman whose heroin addiction, undeterred by twelve stints in drug rehabilitation, led both to her imprisonment and the loss of custody of her daughter. Following her release from prison, Michelle returned to the working-class Detroit suburb where she was raised and moved in with her father and step-mother. Her family provided food, transportation and other necessities, but required that she pay $150 in rent monthly, $100 of which they set aside for her in a savings account. In order to earn rent money, and because she liked to keep busy while she worked hard to stay clean, she began applying for jobs at the many service-sector employers in her suburb. A little over a month following her release, a relative provided her with a referral that landed her a part-time position in a fast-food restaurant.

About a month later she secured another position, this time waitressing 40 hours per week at a nearby diner. These positions allowed Michelle to pay off her parole and driver’s license fees, a significant barrier to transportation facing many of our subjects in a state that invests relatively little in public transportation. Further, they helped her work towards a longer-term goal of establishing custody of her daughter, who was living with Michelle’s mother. In order to gain custody, Michelle had to establish both her own apartment and a record of sobriety, and her jobs helped her advance towards both of these goals.

About a month later she quit the fast-food job over a conflict with her boss and dissatisfaction with her pay, but continued working full-time at the diner. Not long thereafter, Michelle and her boss “got into it” at the diner and Michelle was fired. A customer Michelle had gotten to know through her work at the diner witnessed the exchange and offered to connect her with a new job with his sister’s company. The very next day she had secured part-time work conducting surveys at the mall near her house. For a short time, she also supplemented this position working at a grocery store, but ultimately gave up this second position when she was able to secure full-time employment at the mall. Not long after starting this full-time job, she had a major heroin relapse. She was able to continue working while using heroin for a while, but eventually lost the job. Around this time her father started using drugs again too, and he kicked her out of the house. With nowhere to stay, she was forced to live in a hotel, where she lived until her ex-boyfriend’s mother offered her a home while she straightened out. Shortly thereafter, she and her ex reconnected. They soon moved in together to their own apartment and Michelle secured another waitressing job at a nearby diner. About a year later, Michelle and her (now) fiancé moved into a two-bedroom apartment, and her daughter joined the household shortly thereafter. Toward the end of the study period, Michelle again experienced a drug relapse and was arrested for possession. Having failed to show-up for court-mandated drug screening, she spent a short period of time in jail. Yet despite these periods of relapse and struggle, Michelle was able to stabilize economically by combining employment with social support.

She was able to maintain employment because she nearly always had a stable, low-cost place to stay, transportation to and from work, and at least initially, no childcare responsibilities to interfere with work. She could also turn to her social network to secure new employment when needed. Further, the suburban neighborhoods where she lived with her father and her boyfriend were, unlike many Michigan central cities, relatively prosperous, and provided more low-skill service sector job opportunities. Finally, she was young, white and blond, with some college education and an assertive personality. She reported that potential employers never asked her if she had a criminal record, likely because her appearance and demographic characteristics did not fit their image of a former prisoner.

Michelle’s experience contrasts markedly with that of Jada, a comparison that reveals how crucial employment is for stability, economic as well as emotional. Jada is an African-American mother of two in her early 30’s living in a small, impoverished community on the outskirts of Detroit. Prior to her arrest Jada had been working as a nurse’s aide, earning $12.50 per hour. While she was working, her boyfriend, the father of her youngest child, sold marijuana out of their house. During a raid of her house, the police discovered marijuana and a gun. Although both belonged to her boyfriend, at his behest she claimed the gun was hers. He was already on probation and a weapons conviction would mean he would be sent to prison for a long time. Neither she nor her boyfriend thought prison was likely for her. And it may not have been, had she not been caught smuggling marijuana into prison for him a few months later.

Upon Jada’s release from prison she worried about finding a job. As a felon, she was no longer eligible to work in nursing, and because she had two felony convictions, she would not be able to expunge her record. The only lucrative occupation she had ever had was now closed to her. Further, she did not have the supportive networks of Michelle and knew no one who could help connect her with a new job. Her mother worked as a teacher’s aide, a position also closed to those with a felony conviction, and her sister was on welfare. Over the two years following her release she was employed for less than two months. Initially, she searched for a job every day, submitting resumes and looking online for openings. As the months dragged on, her efforts dropped off. When she heard about a job lead or a business that hired felons, she would often apply, but nothing resulted. Jada appeared to suffer from depression, and in interviews she was often disengaged, irritable and pessimistic. Undoubtedly, her affect hampered her job search, but so too did her long period of unemployment fuel her hopelessness. During one memorable interview, the normally reserved Jada broke down in tears, sobbing, “I just want a job so bad!”

In marked contrast to Michelle, Jada’s job search yielded nothing. Her long work history and absence of substance abuse problems should have given her an advantage over Michelle, but Jada was shut out of the one career path she had known and knew no one who could refer her to a job. Jobs were scarce in her neighborhood, and those open to felons even scarcer, although she did have access to a car and drove considerable distance to apply for jobs early in her job search. Finally, unlike Michelle, no employers took a chance with Jada. Race likely played a role, as did her increasingly frustrated self-presentation. Jobless, Jada subsisted entirely on food stamps, meager welfare benefits, and hand-outs from friends and family. Her rent was paid almost entirely by Section 8, and she and her children received Medicaid. The family subsisted on less than $900 per month, $400 of which was food stamps. She grappled every day with the reality that when her welfare time-limit ran out, her situation would only worsen.

Though this comparison highlights the fact that employment can lead to economic security, it is important to note that employment does not necessarily lead to economic security. For some, health problems or addiction got in the way of effectively searching for and maintaining a job, despite having the requisite human capital and social networks necessary to secure employment. For others, barriers to employment such as the absence of childcare or transportation meant that jobs, once secured, had to be abandoned.

Social Support

Almost all prisoners leave prison with little more than the clothes on their backs. For those who do not move directly into a treatment program or other institutional living situation, family, friends, or romantic partners remain the only housing option, aside from a homeless shelter. All but four of the fifteen male subjects lived with family or romantic partners immediately after their release, including romantic partners (4); parents (6); and siblings (1). Only one male subject (Lamar) remained independent throughout the study period (living with a brother only during the first week after his release). All but two of the seven female subjects lived with family or romantic partners immediately after their release, including: romantic partners (2) and parents (3). The remaining two subjects lived initially in institutional arrangements (a treatment program and an adult foster care facility) and were later housed by family and a romantic partner. While female subjects did not always rely on resources provided through social support, all gained material resources from social support at some point during the study period. Family support provides not just an immediate place to live and meals to eat, but transportation, emotional sustenance, and a stable base from which to develop longer-term strategies for securing shelter and employment. Hence, social support can be integral to economic security, as illustrated by comparing the experiences of Lamar and DeAngelo.

Lamar is a single African-American man in his forties with no children who served two prison terms for armed robbery. A high school graduate raised in a foster family, Lamar got involved in the “party scene” in his late teens and early twenties, and eventually committed multiple armed robberies. At our first interview, Lamar was being paroled for the third time. Upon release Lamar lived for a week with his foster brother before moving to the city’s homeless shelter. Though Lamar’s foster family was emotionally supportive, this short period of housing assistance was the primary material resource they offered during his transition. Absent additional resources, Lamar relied heavily on a soup kitchen and food stamps for food and a homeless shelter for housing while he pursued a dogged strategy of job application. He estimates that he applied for over 200 jobs in the months after release. His persistence paid off with two part-time jobs, one stocking shelves and another in a fast-food restaurant. With these new sources of income and help from the state’s prisoner reentry program, he secured a subsidized room in a boarding house. Meanwhile, he also continued to “party” and use cocaine on the weekends, carefully timing his use to avoid detection by his parole officer. Soon thereafter Lamar landed a full-time job as a line cook, but then lost that job after a conflict with the manager. Not long before his room subsidy was set to run out, he got a job as a taxi driver, and with this new income, meager savings and some help from the reentry program, he secured his own apartment.

At this point, by his own admission, he became a little too comfortable with his new economic stability and success on parole and began to make mistakes. Lamar skipped appointments with his parole officer when they coincided with the most lucrative taxi shifts, bought some stolen money orders from a neighbor for a fraction of their face value, and was accused by his sister-in-law of stealing and pawning jewelry (though this later turned out to be a misunderstanding). This was enough to result in another parole violation, and he was returned to prison for almost a year. All of the progress he had made toward economic stability and all of the possessions he accumulated were lost when he was arrested and returned to prison. Almost two years after his last parole, he was paroled again, returning to a rooming house for parolees, but this time entering into a recessionary economy. Once more deploying his strategy of applying for every job he could, Lamar eventually secured a food service job through a temp service and rented a small apartment of his own, but lost the apartment when the job failed to become permanent. Over three years after we first met him, Lamar moved back to the homeless shelter. He had little to fall back on besides his own tenacity in searching out employment and social services. Because these were often short term, he was frequently left at risk of homelessness.

In contrast, DeAngelo was able to rely heavily on the social support of romantic partners, who provided housing, food, and other forms of assistance. DeAngelo is also an African-American man. He was in his late 20s when he was paroled after his second term in prison, having been sentenced to prison first for breaking and entering and then for drunken driving. DeAngelo has a young son, and he separated from his wife prior to his most recent incarceration. He describes himself as an alcoholic and struggled with a number of related mental health issues including depression, anxiety, and bi-polar disorder. Upon his prison release, DeAngelo moved in with his girlfriend and her mother. This home permitted him a period of re-adjustment to life outside of prison and gave him the time needed to secure health insurance through a county program, begin treatment for his mental health problems and addiction, and look for a job that paid a living wage. His girlfriend also shuttled him to appointments and job interviews because he had lost his license following his drunken driving conviction. DeAngelo had worked as a waiter in the past, and eventually found a position waiting tables at a chain restaurant nearby, making between $13 and $15 per hour, depending on tips.

About three months after his release, DeAngelo moved out of his girlfriend’s mother’s house, and with the help of the state’s reentry program, first got a subsidized room in a boarding house and then his own apartment. The relationship had frayed; his girlfriend had her own mental health problems, and the two of them were constantly fighting. DeAngelo began taking courses in auto body repair, and a new romantic partner moved in to his apartment. She had her own public benefits and cared both for her own child and DeAngelo’s son. His employment did not last long after he realized that their household could get by on his girlfriend’s benefits and his financial aid. About nine months after his release from prison, he was arrested again, this time for driving without a license, and was returned to prison for a technical violation.

DeAngelo served another six months in prison and, like Lamar, lost everything he owned when the landlord emptied his apartment for nonpayment of rent. When he was paroled again he went immediately to a subsidized apartment provided by the state reentry program. He quickly reconnected with the first girlfriend, who in the meantime had begun dancing at a club and established her own household. She drove him to appointments and interviews on her days off and helped him with groceries. When his time in the subsidized apartment was up, DeAngelo moved in with this girlfriend and his son. The girlfriend quit her job, applied for and received SSI, and helped care for DeAngelo’s son. The couple made ends meet with her SSI benefits and help from her family, supplemented by some income DeAngelo made by cutting hair and doing odd jobs. Four months later he found another restaurant job, this time as a line cook at a restaurant two bus rides from home. Then he broke up with his girlfriend again. Without her support, he lost his access to reliable transportation and a babysitter, and a few months later he lost his job after his schedule changed and he could not get to work on Sundays on the bus or work in the evenings because he needed to care for his son. He has since enrolled in a culinary class while his son is in school and makes ends meet by selling beauty products, cutting hair, and doing odd jobs. He is behind on bills but managing to make rent every month, at least for now.

DeAngelo’s experiences illustrate the importance of social support for achieving and maintaining stability of basic material resources. In his case, romantic partners buffered him from homelessness and the effects of unemployment and provided other forms of material support, particularly transportation that facilitated his access to health care and employment. In contrast, Lamar had no such support, and more frequently dropped from a state of stability to that of survival or desperation.

While DeAngelo’s experience demonstrates the importance of social support, social support is not always sufficient to achieve economic stability in the long term. Whether social support could be leveraged into a long-term trajectory of economic stability was dependent on the quality of resources the family could offer as well as characteristics of the family. While some families offered access to extensive job networks and material resources, for instance, other family members were themselves out of work and struggling financially. Further, some family members’ own emotional disorders or addictions meant that the support they offered could pose a danger to our subjects’ own sobriety or emotional stability.

Public Benefits

For those subjects who qualify for them, public benefits such as SSI or Section 8 can provide a basis for long-term economic security, particularly if supplemented with other sources of income.13 However, they are typically too little to leverage into upward mobility. Public benefits are hard to obtain, requiring medical proof of disability in the case of SSI or making it to the top of a waiting list in the case of Section 8. While many of our subjects received Medicaid and obtained food stamps to supplement their food budgets, only those few able to access substantial, long-term public benefits were able to achieve economic security as a result of this resource. Further, short-term or nominal benefits never served as a stepping-stone to sustained economic security.

Of the fifteen male subjects, only one was supported primarily by public benefits (Damian, who was elderly and received SSI) and four male subjects never received public benefits. Eight of the male subjects were supported in part by public benefits received by romantic partners and family, and at least nine of the male subjects received some food assistance via SNAP and/or housing and transportation resources, which were provided to some subjects through the state prisoner reentry program. All seven female subjects received some resources through public assistance. Two gained support in part through family members’ public benefits; three relied predominantly on their own public assistance (SSI and TANF), and six received food assistance and/or housing and transportation resources.

The significant role that public benefits can play in economic stability can be seen in the comparison between Jennifer and Lenora. Jennifer, 38, is a single white woman with two grown children and one adolescent. She gave birth to the first of these children at 13, at which point she dropped out of school. The next twenty-five years were spent selling drugs, using drugs or in jail. Upon her prison release she received substantial material support from family and a former “fiancé,” with whom she was no longer romantically involved. She initially relied upon this fiancé for housing, food and transportation. A few months later, her sisters were able to purchase a trailer from an elderly relative for Jennifer. They also provided the money needed to move the trailer to a “felon-friendly” trailer park and pay the first month’s lot rent. Set up in her own home, Jennifer was able to regain custody of her young son. Her son brought with him $125 he received in foods stamps monthly, and the SSI payments he received on behalf of his father, who suffered from rheumatoid arthritis. These benefits provided a source of economic stability while Jennifer sought out her own government benefits; applying for Medicaid, SSI, food stamps and TANF. Her TANF and food stamp award granted her an additional $600 per month. Soon after she was approved for SSI, both for illiteracy and the chronic injuries she had sustained as a result of a car accident. She and her son together received roughly $1100 monthly in government benefits, which her sisters and girlfriend supplemented occasionally with money or food stamps, as needed. With the help of a great deal of family support, substantial government benefits, and a strong commitment to sobriety Jennifer made it: attaining economic stability (albeit at a level below the poverty line) and never relapsing or committing another crime.14

In contrast, Lenora, an African American woman in her fifties released from her eighth prison bit, was unable to establish substantial long-term benefits and, thus, never stabilized. This was true despite the fact that Lenora had an extensive employment history and was resourceful, motivated and energetic. Lenora was an alcoholic and occasional hard drug user since her teenage years. To support her habit she engaged in “retail fraud,” stealing from stores and selling the items on the street. Prior to her most recent prison term, she had been employed as a presser at a drycleaner for three years. Upon release, she brought this energy and enthusiasm to her job search, as well as her search for charitable and government benefits. She first landed in a halfway house in Detroit, and for four months the state’s prisoner reentry initiative covered food and rent. At the halfway house, she and the other residents were required to be out of the house for the entire day, searching for jobs. She stopped by a university in Detroit, and discovered that she qualified for financial aid. She signed up, believing that financial aid could be her “ticket out,” a financial resource that would allow her to establish permanent housing and buy a car.

Over the following months she took advantage of jobs skills training at Goodwill Industries, free clothing at a local charity, a short-term position subsidized by the reentry initiative and supports and services offered from a number of other Detroit-area charities. And yet her frustration at not being able to get a full-time, permanent job led to a several-month bout of relapse and retail fraud that ended when she was assigned to inpatient drug treatment. Both the relapse and the inpatient residence disrupted her educational plans, compromising her chance for additional loans and grants. Following her completion of the inpatient treatment program, she stayed on as a resident trainee for four months, earning $75 a week plus room and board. She hoped to be hired on to a permanent position. She was not, and thereafter moved in with her nephew, paying $300 in rent a month and subsisting on food stamps and sporadic temporary employment. The last we saw of Lenora, her nephew’s house was being foreclosed upon and she was planning to move, possibly into a homeless shelter. She admitted that her stress at having no income aside from food stamps and the threat of losing her housing had led her back to drinking, and drinking triggered thoughts of stealing. Despite Lenora’s resourcefulness, accessing a half dozen charitable organizations, employment support, transitional housing services and educational financial aid, the short-term nature of each of these supports never provided her with economic security. Each employment or housing opportunity came with a time limit, after which she had to struggle again to meet her basic needs. Though Lenora sought out public benefits, unlike Jennifer, she was never eligible for those that provided longer term stability. The comparison between Jennifer and Lenora reveals the importance of substantial public benefits for economic security among former prisoners who struggle with employment. While many of our subjects pursued long-term benefits such as SSI, only a few were able to secure them. And for those few, economic security became more possible.

Achieving Upward Mobility

Four of our subjects achieved upward mobility that resulted in significant promise for long-term economic security and a middle-class lifestyle. We now turn to the question of how they did so. We find that strong and sustained social support, usually from family or a romantic partner with considerable social and economic resources, was the primary path to upward mobility. For example, family or partners who could actively assist with employment by harnessing the social capital of their own job networks contributed to better paying jobs with possibilities for career advancement. Abundant family or partner resources also give former prisoners access to communities and institutions that promote upward mobility. The comparison between Randall and Leon illustrates the importance of family assistance for finding a job.

Randall is an African-American man in his late thirties who had been in prison for drug dealing, car theft, and firearm possession. Although there was no evidence that Randall had a substance abuse problem, he paroled to a drug treatment program (largely because he had nowhere else to go) and then spent a week in a homeless shelter before moving in with his brother, sister-in-law, and their two teenage sons. Unable to find a job, Randall contributed his food stamp benefits to the household, did odd jobs for other family members, and briefly sold marijuana to generate a small income. He initially expected that his brother or cousin would connect him to a job at their places of employment, but no job opportunity was provided, much to Randall’s disappointment. After two months, Randall’s brother, who had a drinking problem and was verbally abusive, told Randall that the housing situation was only temporary. Randall moved out, reporting that his brother’s family used all of his food stamps and that he no longer wanted a relationship with this brother. He stayed in a series of short term housing situations, even once living in an abandoned house in the dead of winter, and eventually landed in a more permanent arrangement with his step sister and her father. Living in Detroit far from most work opportunities and with less than a high school education, weak soft skills, no recent work experience, and a long list of felonies, Randall was never able to find a job while living with his uncle, a retired blue collar worker, and younger, predominantly unemployed, step sister. The two lacked the social capital that could have helped Randall secure employment. At various points in time he returned briefly to drug dealing, sold plasma, and served a month in jail for stealing a cell phone. Eventually he moved out of the house to live with his fiancé and her son in the suburbs. Finally, nearly three years after his release from prison and with the help of his fiancé in completing online job applications, Randall finally landed a job as a line cook at a restaurant.

Leon also received considerable social support from relatives, but in contrast to Randall, the form and extent of that support helped Leon to relatively quickly secure a well-paying job that led to upward mobility. Leon is an African-American man in his mid-thirties who served time in prison for armed robbery. He has an 11-year old son and was separated from his wife before he was incarcerated. Although Leon went to college for two years, his drug addiction landed him in trouble. When paroled, he moved in with his father, then to a halfway house in order to qualify for a rent subsidy in the future. After a conflict with the halfway house manager, he moved in with his sister. Leon’s job search was frustrating at first, as he applied for over 40 jobs with little response. Those that did respond were difficult to get to or were not jobs in which he was interested. Then Leon’s uncle connected him with a friend who ran a non-profit organization, and he landed a temporary job. After three months on this provisional status, he became a regular full-time employee with benefits, and then rose further up the ranks in the organization to a position of greater responsibility and slightly higher pay. With this job security, Leon and his girlfriend, who also worked, moved into an apartment of their own. Leon saw his son every week and voluntarily contributed $300 a month in child support. He was constantly on the lookout for an even better job, and when the study concluded, was starting to think about returning to college to finish his degree.

Leon’s experience illustrates the power of social support to launch a former prisoner on an upward trajectory. His father and sister met his basic needs while his job search began, which allowed him the flexibility to await a better job offer. More importantly, his uncle used his social networks to find Leon a job that was appropriate for his level of education and provided the opportunity for upward mobility, initiating Leon’s social and economic reintegration. In contrast, while Randall also received considerable social support, that support was difficult to sustain and only sufficient to meet his most basic material needs, as his family was unable to provide the type of social resources that were critical to Leon’s success.

A second comparison that reveals the importance of family social support and job networks for upward mobility is that between Daniel and Jake. Daniel, a single white male in his early thirties with no children, got involved with drugs in his mid-teens, and was regularly carrying a gun by age 17. As a 21-year-old, Daniel and a friend decided to rob an associate, and in so doing, Daniel shot the man in the back of the head. His only previous offense had been loitering in a house that was being monitored for drug activity. After serving 12 years for manslaughter, Daniel moved in with his father and stepmother, who were both retired and living on social security benefits. He lived at this residence for close to a year and a half. While Daniel made some attempts to look for other housing during this period, he was not pressured to move or to contribute rent or household expenses until after he found a job, at which point he was asked to contribute $75 per month. In addition, Daniel enjoyed the benefits of a high school diploma and freedom from the addictions that plagued many of our other subjects.

With a stable residence and basic needs met, Daniel was able to take the time to seek out a job with long-term career prospects. Although before prison Daniel made the majority of his income selling drugs, he had also had legitimate work experience as a forklift driver. While he remained willing to work for low-wage jobs and had applied to a few, he also scoured his social network, trying to find job opportunities through his neighbors, brothers, and friends. More than six months after release, he started his first job, which he located through a family friend. He worked full-time for a janitorial supply company—eventually receiving benefits—while he also pursued his longer term career goal, employment as a physical trainer.

Once Daniel became a full-time personal trainer, he was able to move into his own apartment. Stably employed, he applied for grants to further his education in nutrition and personal training. While Daniel benefited from a strong drive to succeed and a commitment to his career, he also benefited every step of the way from family support and a social network that provided him with the resources to pursue this interest. His family paid for his initial gym membership; his sister drove him to appointments; his father let him take his car to drive to his first job; he found the job at the gym through a friend; his mother put him on her credit card so he could improve his credit score; and his cousin helped him find his first apartment.

In contrast, although Jake achieved a level of basic economic security, he did not have the type of social support that Daniel leveraged into upward mobility. Jake is a white male in his late twenties who had been sent to prison for a second drunken driving offense, the result of alcoholism. Upon release, Jake moved into his father’s house, where he lived for over a year. Jake actually gained full-time employment (at a restaurant) much more quickly than Daniel, largely because he had worked at the restaurant prior to his imprisonment. His next job (with a car mechanic) was found through a job search and application process. Although he initially thought that a restaurant where his sister was a manager might yield a job, he never ended up working there. He also believed that he might get a job at a car manufacturer through his father, but he would have had to move to Tennessee, and the certainty of this opportunity was unclear. Furthermore, Jake contributed a significant amount to his parents’ households. By the time he had his second job he was living alone in his father’s house and paying $525 per month in rent, similar to what he would have paid for an apartment of his own. While his mother initially provided him with transportation, he did not receive much else in terms of support from family.

Moreover, the people in Jake’s social network faced many adversities of their own, making it difficult for them to provide much in the way of support. His only romantic partner during this period was introduced to him while she was in prison, and he later separated from her because she relapsed after being diagnosed with cervical cancer. One of his three sisters was on probation and married his prison bunk mate, causing tension in their relationship. He had a good relationship with his mother, but she was diagnosed with cancer and later moved out of the state.

Thus, while Jake was able to attain some degree of security and stability through employment, his social network did not provide him with the resources to be upwardly mobile. Daniel, however, did have a very strong support network that helped him not only to attain employment but to secure the kind of employment – with benefits and higher wages – that led to upward mobility. The comparisons between Daniel and Jake and Randall and Leon illustrate just how important a strong social network can be for upward mobility after prison.

Conclusion