Abstract

Hypercholesterolemia and polymorphisms in the cholesterol exporter ABCA1 are linked to age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Excessive iron in retina also has a link to AMD pathogenesis. Whether these findings mean a biological/molecular connection between iron and cholesterol is not known. Here we examined the relationship between retinal iron and cholesterol using a mouse model (Hfe−/−) of hemochromatosis, a genetic disorder of iron overload. We compared the expression of the cholesterol efflux transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 and cholesterol content in wild type and Hfe−/− mouse retinas. We also investigated the expression of Bdh2, the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of the endogenous siderophore 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,5-DHBA) in wild type and Hfe−/− mouse retinas, and the influence of this siderophore on ABCA1/ABCG1 expression in retinal pigment epithelium. We found that ABCA1 and ABCG1 were expressed in all retinal cell types, and that their expression was decreased in Hfe−/− retina. This was accompanied with an increase in retinal cholesterol content. Bdh2 was also expressed in all retinal cell types, and its expression was decreased in hemochromatosis. In ARPE-19 cells, 2,5-DHBA increased ABCA1/ABCG1 expression and decreased cholesterol content. This was not due to depletion of free iron because 2,5-DHBA (a siderophore) and deferiprone (an iron chelator) had opposite effects on transferrin receptor expression and ferritin levels. We conclude that iron is a regulator of cholesterol homeostasis in retina and that removal of cholesterol from retinal cells is impaired in hemochromatosis. Since excessive cholesterol is pro-inflammatory, hemochromatosis might promote retinal inflammation via cholesterol in AMD.

Keywords: cholesterol transport, hemochromatosis, mammalian siderophore, β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase-2, retinal pigment epithelial cells

1. Introduction

There is overwhelming evidence for the involvement of oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of blindness in adults in developed countries [1–4]. There are two forms of AMD, dry and wet, the former with accumulation of drusen deposits underneath the basal side of the retinal pigment epithelium and the latter with abnormal development of new blood vessels, which invade into the retina through the Bruch’s membrane. There is no consensus on whether or not a similar mechanism participates in the pathogenesis of both forms, but the involvement of oxidative stress and inflammation has been implicated in dry as well as wet AMD. Accordingly, most of the animal models of AMD are based either on disruption of inflammatory pathways such as the complement system or chemokine signaling or on oxidative damage [5].

Iron is essential for the survival of all cells, but excessive iron is detrimental because free iron generates potent reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl radicals. Numerous studies have suggested a role for excessive accumulation of iron in the retina as an important contributor to the pathogenesis of AMD [6–8]. Retina expresses most of the proteins that are known to participate in the regulation of iron homeostasis, a feature obligatory for maintenance of iron levels optimal for cellular function without the risk of oxidative stress [9]. Disruptions in the expression and function of these iron-regulatory proteins alter iron levels in the retina, involving all retinal cell types. Hemochromatosis is a hereditary disorder caused by loss-of-function mutations in five different genes coding for iron-regulatory proteins, namely HFE, hemojuvelin (also called HFE2), hepcidin (also called HAMP), ferroportin, and transferrin receptor 2 (TfR2) [10–13]. This disorder represents one of most prevalent genetic diseases in humans, with homozygosity or compound heterozygosity accounting for 1 in 300 in the general population. Mutations in HFE are seen in >85% of patients with hemochromatosis, the remaining ~15% arising from mutations in the other four genes. Irrespective of the gene involved, hemochromatosis is associated with excessive iron accumulation in multiple systemic organs, leading to oxidative stress and consequent organ dysfunction. It was believed for a long time that the retina and the brain are spared in this disease because of the blood-retinal barrier or blood-brain barrier, but emerging evidence strongly indicates otherwise [9, 14]. Mouse models of hemochromatosis (Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and hepcidin−/− mice) have provided unequivocal evidence for excessive iron accumulation in the retina in this disease [15–17]. These mice exhibit morphological and biological changes in the retina that are similar to those found in AMD [15–17], indicating that iron-mediated oxidative stress is likely to be a critical determinant in the pathogenesis and/or progression of AMD.

With regard to the role of inflammation in AMD, available evidence points to the involvement of diverse immune cell types, cytokines, and signaling pathways [3, 4]. Cholesterol is receiving increasing attention in recent years as a critical determinant of inflammatory pathways [18–20], and two transporters, ABCA1 and ABCG1, both participating in the efflux of cholesterol from peripheral tissues to load it to on HDL, have been implicated in this process [21, 22]. Furthermore, there is strong evidence from animal models of hypercholesterolemia for excessive cholesterol build-up in the retina as a causative factor in AMD [23–26].

From what has been described above, it is likely that excessive iron in retina may contribute to the pathogenesis/progression of AMD through oxidative damage and that excessive cholesterol in retina may also contribute to the pathogenesis/progression of AMD through inflammation. However, whether there is any link between iron and cholesterol in health and disease is not known. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the expression of the cholesterol efflux transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 in the retina in normal mice and in a mouse model of hemochromatosis (Hfe−/− mouse) and also to determine how the iron status in retina and RPE influences the expression of these two transporters. Furthermore, there has been a recent development in the area of iron homeostasis in mammalian cells, which involves identification of an endogenous siderophore (i.e., iron carrier) and the enzyme critical for its synthesis [27]. The siderophore is 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,5-DHBA) and the enzyme is the cytosolic β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase, known as Bdh2. This siderophore binds iron and facilitates its entry through plasma membrane and mitochondrial inner membrane [27]. There is no information available at present on the expression of Bdh2 and on the role, if any, for the newly discovered endogenous siderophore in the retina; therefore, here we studied the expression of this important iron-regulatory enzyme in the retina in wild type and Hfe−/− mice and also examined the influence of the siderophore 2,5-DHBA on the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in RPE cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Antibodies were obtained from the following sources: rabbit polyclonal anti-ABCA1 and rabbit polyclonal anti-ABCG1 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), goat polyclonal anti-Bdh2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-vimentin (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and chicken anti-MCT1 (Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX, USA), goat anti-rabbit IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 568, donkey anti-goat IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 568, goat anti-chicken IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 568, and goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The dilutions of the antibodies used for immunofluorescence experiments were: 1:1000 for ABCA1, 1:25 for ABCG1, 1:50 for vimentin, 1:50 for Bdh2, and 1:1000 for MCT1. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for L-ferritin and H-ferritin were provided by Professor P. Arosio (Dipartimento Materno Infantile e Tecnologie Biomediche, Universita di Brescia, Brescia, Italy).

2.2. Animals

Breeding pairs of Hfe+/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Age- and gender-matched wild type and Hfe−/− mice were obtained from the same litter originating from the mating of heterozygous mice. Albino Balb/c mice (6-week-old) were used for immunofluorescence analyses in some studies. Mice were purchased from Harlan-Sprague Dawley, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN, USA). All experimental procedures involving these animals adhered to the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (National Institutes of Health publication #85-23, revised in 1985) and were approved by the Institutional Committee for Animal Use in Research and Education.

2.3. Immunofluorescence analysis

Eyes were embedded in OCT compound and frozen at –20 °C. Sections (8-µm thick) were used for immunostaining by fixing in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, washed with 0.01M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4), and blocked with 1X Power Block for 60 min. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with appropriate primary antibodies. Negative controls involved omission of the primary antibodies. Sections were rinsed and incubated for 1 h with appropriate secondary antibodies. Coverslips were mounted after staining with Hoechst nuclear stain and sections were examined by epifluorescence microscopy (Axioplan-2 microscope, equipped with an HRM camera and the Axiovision imaging program; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

2.4. Primary RPE, Müller, and Ganglion cell cultures from mouse eyes

Primary cultures of RPE were prepared as described previously [15, 17]. Three-week-old wild type and Hfe−/− mice were used to establish primary cultures of RPE. The purity of the culture was verified by immunodetection of RPE-65 (retinal pigment epithelial protein 65) and CRALBP (cellular retinaldehyde binding protein). Müller cells were prepared from 7- to 10-day-old C57BL/6 mice by a method adapted from Hicks and Courtois [28] and described in one of our previous publications [29]. Staining for the Müller cell markers glutamine synthetase, glutamate transporter EAAT1, and CRALBP confirmed the purity of the primary cultures. Retinal ganglion cells were isolated by immunopanning from 2-day-old C57BL/6 mice by the method of Barres et al. [30] as described previously in our publications [31, 32]. The purity of the cultures was confirmed by immunostaining for Thy-1, a ganglion cell marker.

2.5. Real time PCR

The following real time primers were used: 5’-AGTTTCGGTATGGCGGGTTT-3’ (forward) and 5’-AGCATGCCAGCCCTTGTTAT-3’ (reverse) for mouse ABCA1; 5’-ACCTACCACAACCCAGCAGACTTT-3’ (forward) and 5’-GGTGCCAAAGAAACGGGTTCACAT-3’ (reverse) for mouse ABCG1; 5’-GATGCAACTGTGTGTGTCCAGGAA-3’ (forward) and 5’-ACAGGGTTGCCAGTTACATAGGCT-3’ (reverse) for mouse Bdh2; 5’-GAAGTACATCAGAACATGGGC-3’ (forward) and 5’-GATCAAAGCCATGGCTGTAG-3’ (reverse) for human ABCA1; 5’-CAGGAAGATTAGACACTGTGG-3’ (forward) and 5’-GAAAGGGGAATGGAGAGAAG-3’ (reverse) for human ABCG1; 5”-GAGGACGCGCTAGTGTTCTT-3’ (forward) and 5’-TGTGACATTGGCCTTTGTGTT-3’ (reverse) for human transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1). 18S and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 (HPRT1) were used as internal controls. Real-time amplifications using SYBR Green detection chemistry were run in triplicate on 96-well reaction plates. Reactions were prepared in a total volume of 25 µl containing: 5 µl cDNA, 0.5 µl of each 20 µM primer, 12.5 µl of SYBR® Green Supermix and 6.5 µl RNase/DNase-free sterile water. Blank controls were run in triplicate for each master mix. The cycle conditions were set as follows: initial template denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, and combined primer annealing/elongation at 60 °C for 30 s and 70 °C for 45 s. This cycle was followed by a melting curve analysis, ranging from 56 °C to 95 °C, with temperature increasing by steps of 0.5 °C every 10 s. Baseline and threshold values were automatically determined for all plates using the StepOne software. Raw Ct values were transformed to quantities using an Excel spreadsheet. The resulting data were converted into correct input files, according to the requirements of the software, and analyzed for fold change using the Excel spreadsheet.

RNA isolated from whole retina was used for qPCR. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation under isofluorane anesthesia and the eyes were removed. Extraocular tissues connected to the eyeball were removed with scissors, and then a small cut was made on the anterior side of the eyeball to remove the lens and the vitreous. The remaining part consisting of the neural retina, RPE, and choroid was used for preparation of RNA.

2.6. Treatment of primary RPE cells with 5-azacytidine

Wild type and Hfe−/− primary RPE cells were seeded in 6 well plates and treated with the DNA-demethylating agent, 5-azacytidine (5-AzaC; 2 µg/ml) for 24 h. RNA was isolated from the cells for real-time PCR.

2.7. Analysis of ABCG1 and ABCG1 expression in control and DNMT1−/−, DNMT3b−/−, and DNMT1−/−/DNMT3b−/− cancer cells

Control HCT116 cells, a human colon cancer cell line, and isogenic HCT116 cells with deletion of DNMT1 (DNMT1−/−), DNMT3b (DNMT3b−/−), or both (double-knockout or DKO) were originally provided by Dr. Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA). RNA prepared from these cells was used for RT-PCR to determine the role of DNMT1 and DNMT3b in the control of expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1.

2.8. Quantification of cholesterol levels

The levels of total cholesterol in retinal tissue and ARPE-19 cells were measured using a commercially available assay kit (Cell Biolabs, Inc. San Diego, CA, USA). This is a fluorometric assay, which involves the extraction of total cholesterol with chloroform/isopropanol/NP-40. In the case of retinal tissue, lens and vitreous were removed from the eye and the rest of the tissue was used for the assay. The data are presented µM in the tissue/cell extracts; based on the volumes of the tissue extracts that were used in the technique, 1 µM equals 0.8 nmole of cholesterol/retina and 0.67 nmole/mg of protein for ARPE-19 cells.

2.9. Influence of 2,5-DHBA (a siderophore) and deferiprone (an iron chelator) on TfR1 mRNA levels and ferritin protein levels

ARPE-19 cells were cultured in 6-well culture dishes for two days and then treated with 2,5-DHBA (250 µM) or deferiprone (250 µM) for 16 h and then the cells were used for preparation of RNA and protein extracts. Untreated cells were used as the control. Steady-state levels of TfR1 mRNA were monitored by RT-PCR and qPCR. To determine the ferritin levels, protein was extracted from the cells using the lysis buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl buffer, pH 7.6, 50 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetate) containing a cocktail of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The levels of ferritin (heavy chain H as well as light chain L) were monitored by Western blot using specific antibodies. β-Actin was used as the internal control for protein loading in Western blot analysis.

2.10. Statistics

Statistical differences were calculated by paired Student’s t test or by ANOVA as appropriate. A p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in mouse retina and their polarized distribution in RPE

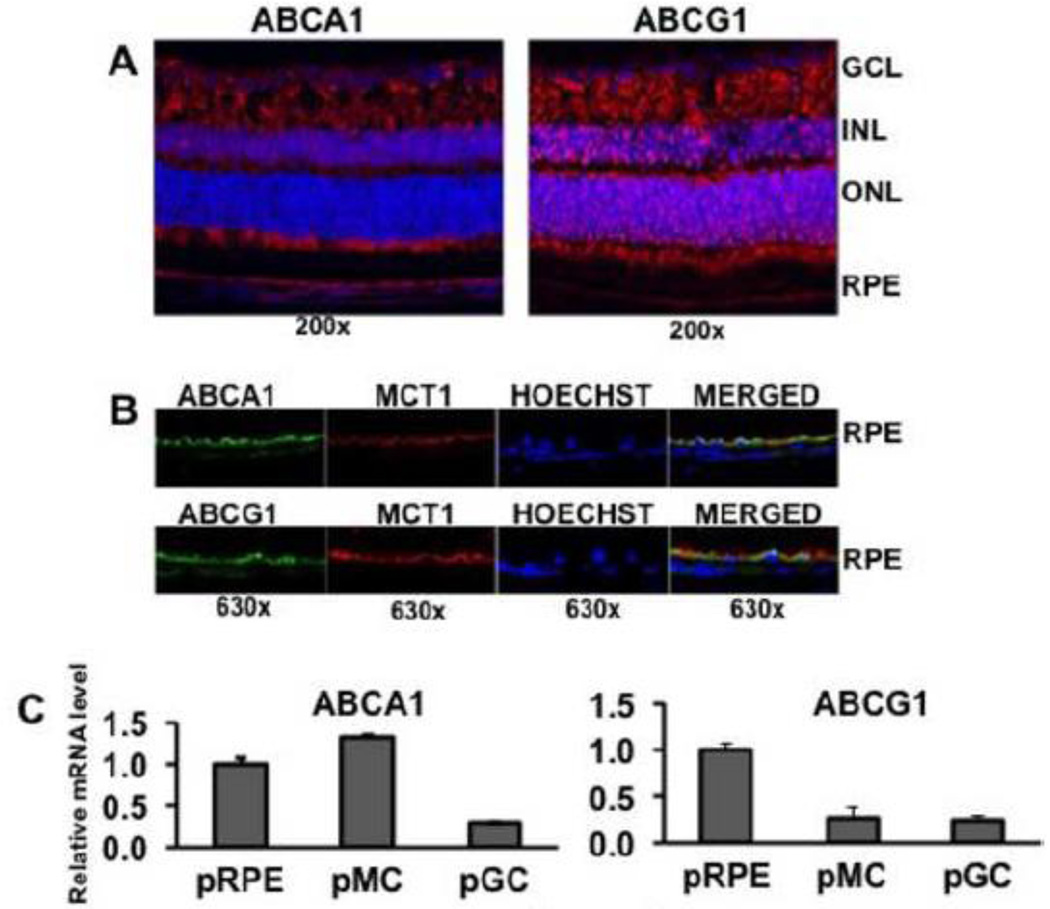

We examined the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in mouse retina by immunofluorescence analysis. We used the albino Balb/c mice for this purpose because the lack of pigment in RPE makes it easy to visualize the polarized distribution of proteins in the basolateral membrane versus apical membrane. Both transporters were robustly expressed in the retina with almost a similar expression pattern (Fig. 1A). The proteins were detectable in all cell layers of the retina, including the RPE. In photoreceptor cells, ABCA1 was detected in the inner segment and ABCG1 in the outer segment. Since RPE is a polarized cell, we examined by confocal microscopy the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in the two poles of the RPE plasma membrane, the apical membrane, which faces the subretinal space and the basolateral membrane, which faces the choroid. We used double-labeling for this purpose with MCT1 (monocarboxylate transporter 1) as the marker for the RPE cell apical membrane [33]. We have used this marker successfully in many of our previously published studies to determine the polarized expression of several transporters and receptors [34–37]. We found ABCA1 as well as ABCG1 to colocalize with MCT1, indicating the presence of both transporters in the apical membrane (Fig. 1B). The basal membrane also was immunopositive for both transporters, but the protein levels in the apical membrane were much higher than in the basal membrane. We confirmed the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in primary mouse retinal ganglion cells, Muller cells, and RPE cells by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). ABCA1 expression was much higher in pRPE and pMC than in pGC; in contrast, ABCG1 expression was much higher in pRPE than in pMC and pGC.

Fig. 1.

Expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in mouse retina. (A) The expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in mouse (Balb/c) frozen retinal sections was studied by immunofluorescence. Red signals indicate the protein expression and blue signals indicate nuclei. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium. (B) The polarized expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in RPE cell apical membrane versus basolateral membrane was studied by double-labeling immunofluorescence using MCT1 as a marker for RPE cell apical membrane. Green, ABCA1 or ABCG1; Red, MCT1; Blue, nuclei. (C) Relative levels of ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNAs in primary cultures of mouse retinal pigment epithelial cells (pRPE), Muller cells (pMC), and ganglion cells (pGC) as assessed by real-time RT-PCR. The mRNA level in pRPE was taken as 1.

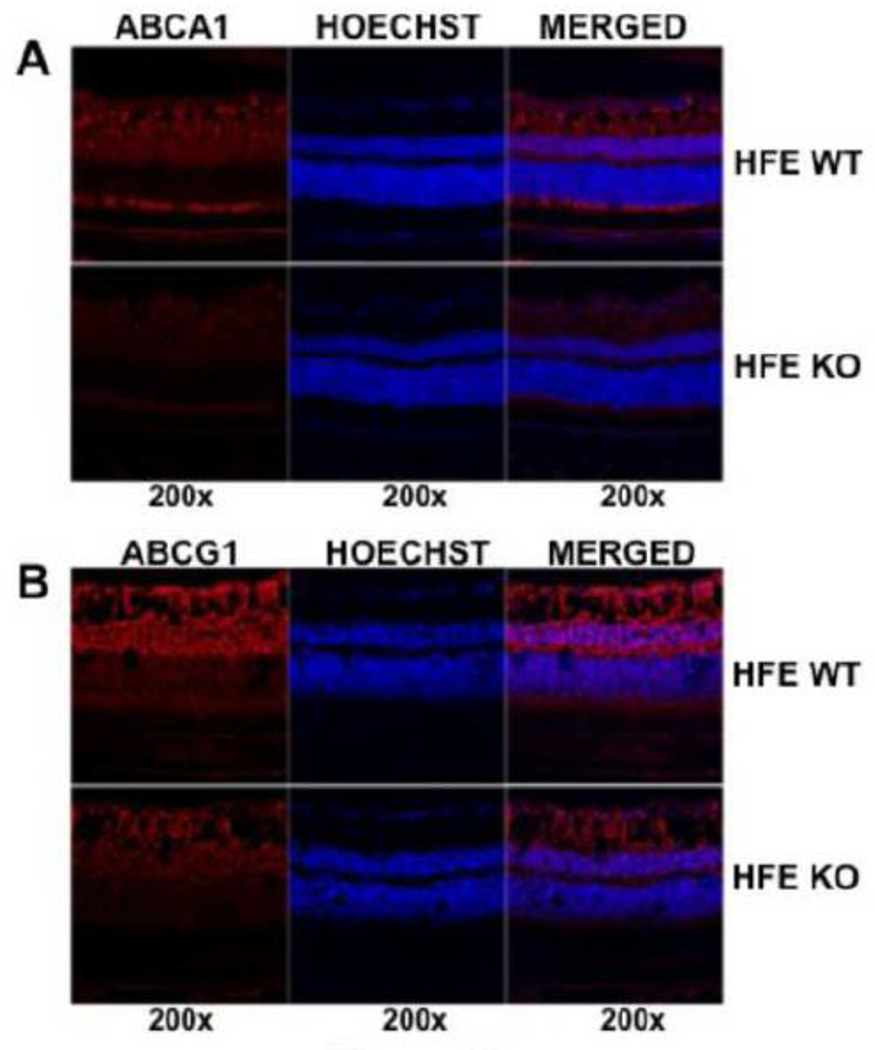

3.2. Downregulation of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in hemochromatosis retina

We then compared the expression of both transporters between wild type mouse retina and Hfe−/− mouse retina. We used 18-month-old mice for these experiments because of our earlier findings that retinal degeneration becomes evident in Hfe−/− mice only at ages older than 1 year [15]. We found the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 to be decreased in Hfe−/− mouse retinas (Fig. 2). The decrease was evident in all cell layers of the retina. This phenomenon was confirmed by corresponding changes in steady-state mRNA levels for both transporters in whole retina (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of ABCA1 and ABCG1 protein expression in the retina between wild type mice (HFE WT) and Hfe−/− mice (HFE KO). (A) Expression of ABCA1 in mouse frozen retinal sections was studied by immunofluorescence. Red signals indicate ABCA1 protein and blue signals indicate nuclei. (B) Expression of ABCG1 in mouse frozen retinal sections was studied by immunofluorescence. Red signals indicate ABCG1 protein and blue signals indicate nuclei. In both cases, age-matched (18-month-old) wild type and Hfe−/− mice were used for preparation of retinal sections.

Fig. 3.

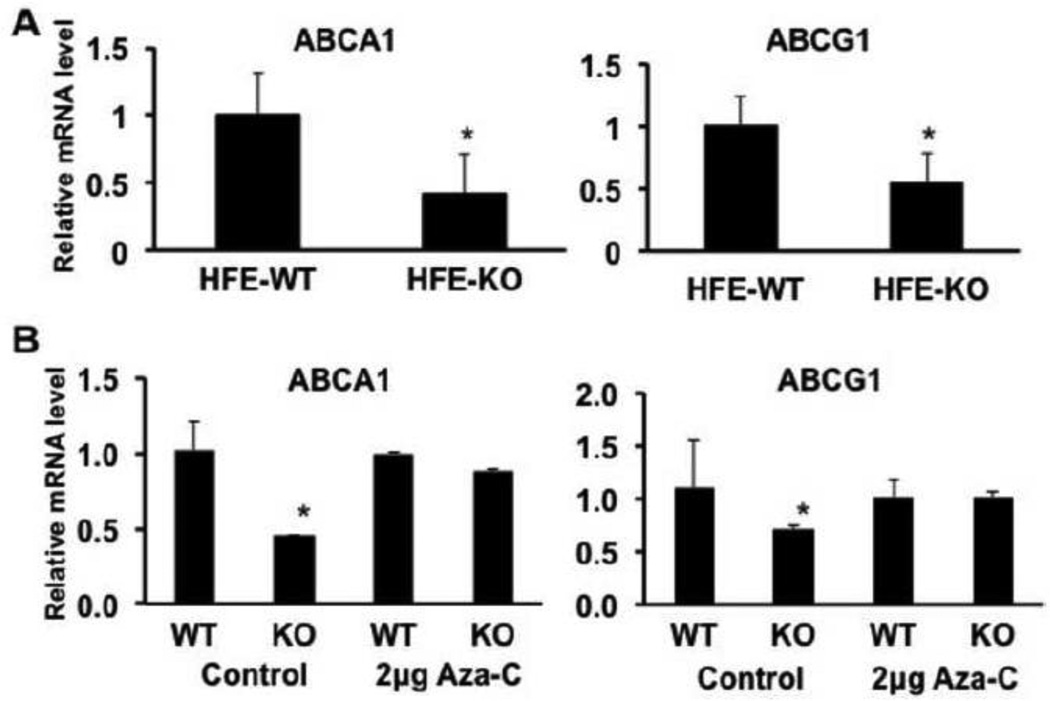

ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNA levels in wild type and Hfe−/− mouse retinas and the role of DNA methylation on the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in RPE. (A) mRNA levels for ABCA1 and ABCG1 were compared between wild type (HFE-WT) and Hfe−/− (HFE-KO) mouse retinas by real-time RT-PCR. *, p < 0.05 compared to HFE-WT by paired Student’s t test. (B) Influence of DNA methylation on ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression in primary cultures of RPE cells. Cells prepared from wild type and Hfe−/− mice were subjected to treatment with and without 5’-azacytidine (2 µg/ml) in the culture medium for 24 h. Following the treatment, RNA was prepared and used for real-time RT-PCR to quantify the levels of ABAC1 and ABCG1 mRNAs. *, p < 0.05 as assessed by ANOVA.

3.3. Involvement of DNA methylation in the suppression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression in Hfe−/− mouse retina

There is evidence for the regulation of ABCA1 expression by promoter methylation [38, 39]; hypermethylation of ABCA1 in the promoter region silences the gene expression. We have shown recently that the levels of DNA methyltransferases are elevated in Hfe−/− mouse RPE cells [40]. These findings led us to hypothesize that the suppression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 observed in Hfe−/− retinas may occur epigenetically through DNA methylation. We tested this hypothesis by studying the influence of the DNA methylation inhibitor 5’-azacytidine on the steady-state levels of mRNA for ABCA1 and ABCG1 in pRPE cells prepared from wild type and Hfe−/− mouse retinas. Without any treatment, the levels of ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression were significantly lower in RPE cells from Hfe−/− mice than in RPE cells from wild type mice (Fig. 3B). Treatment of wild type RPE cells with the DNA methylation inhibitor did not show any significant effect on the expression of both transporters whereas under similar conditions the DNA methylation inhibitor increased the expression of both transporters in Hfe−/− RPE cells (Fig. 3B). In fact, the decrease in mRNA levels observed in Hfe−/− RPE cells compared to wild type RPE cells disappeared after treatment with 5’-azacytidine, suggesting that DNA methylation was almost entirely responsible for the hemochromatosis-associated decrease in the retinal expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1. To determine the identity of DNMT isoform that was responsible for this phenomenon, we used a human colon cancer cell line (HCT116), which is available with and without DNMT1, DNMT3b, or both. These are isogenic cell lines, the only difference being the presence or absence of specific DNMT isoforms. We found the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 to be markedly increased in DNMT1−/−/DNMT3b−/− double-knockout cells (data not shown), suggesting that the hemochromatosis-associated silencing of the cholesterol efflux transporters may similarly require DNMT1 or DNMT3b.

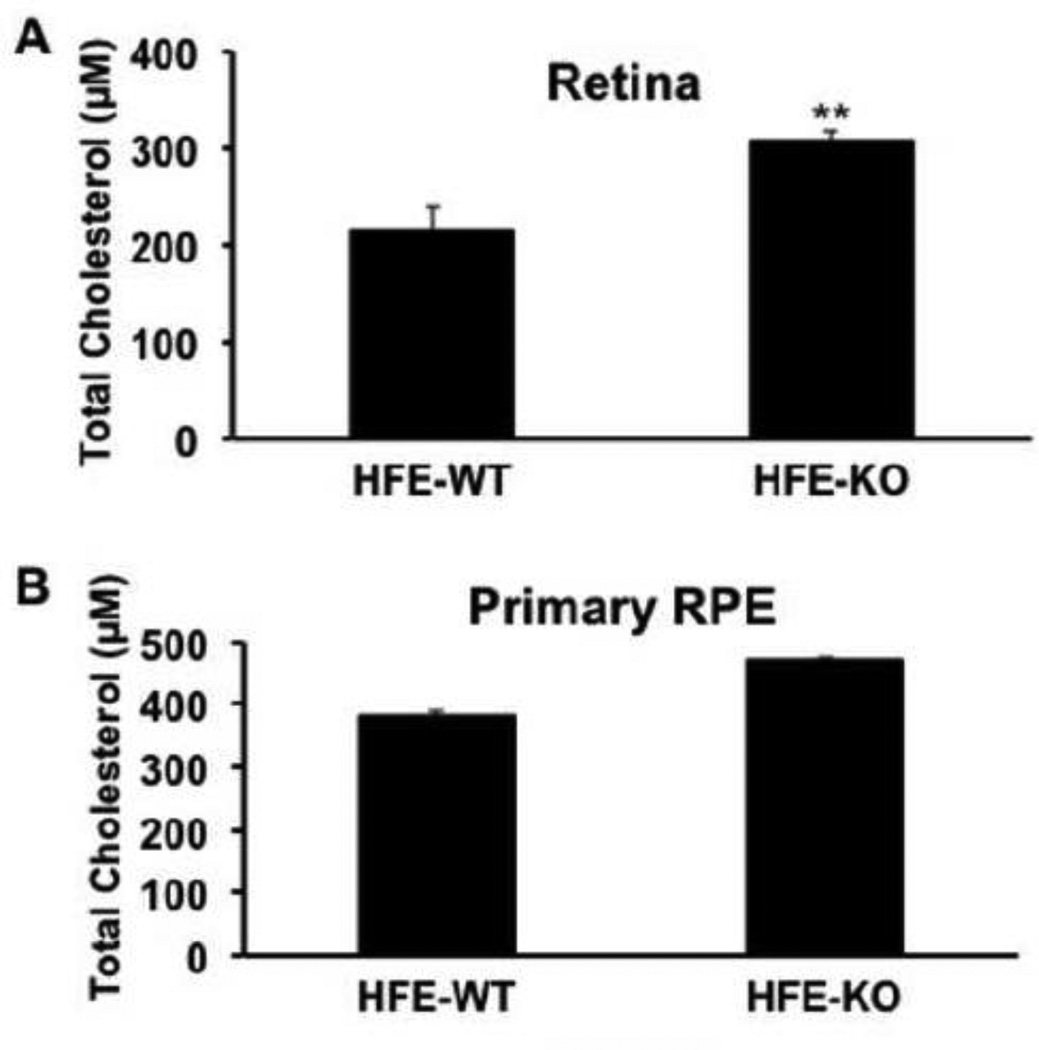

3.4. Retinal and RPE cholesterol levels in wild type and Hfe−/− mice

The function of ABCA1 and ABCG1 is to remove cholesterol from the cells by an active mechanism coupled to ATP hydrolysis. Therefore, the decreased expression of these two transporters in hemochromatosis mouse retina should be associated with increased cholesterol levels. This was indeed the case. The levels of cholesterol in whole retina were significantly higher in Hfe−/− mice than in wild type mice (Fig. 4A). This phenomenon was also observed in primary cultures of RPE cells prepared from wild type mice and Hfe−/− mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Retinal and RPE cholesterol levels in wild type (HFE-WT) and Hfe−/− (HFE-KO) mice. (A) Age-matched (18-month-old) wild type and Hfe−/− mouse retinas were used for measurement of cholesterol. **, p < 0.01 compared to wild type control by paired Student’s t test. (B) Cholesterol content in primary cultures of RPE cells prepared from wild type and Hfe−/− mice. **, p < 0.01 compared to wild type control by paired Student’s t test.

3.5. Effect of the mammalian siderophore 2,5-DHBA on the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in RPE

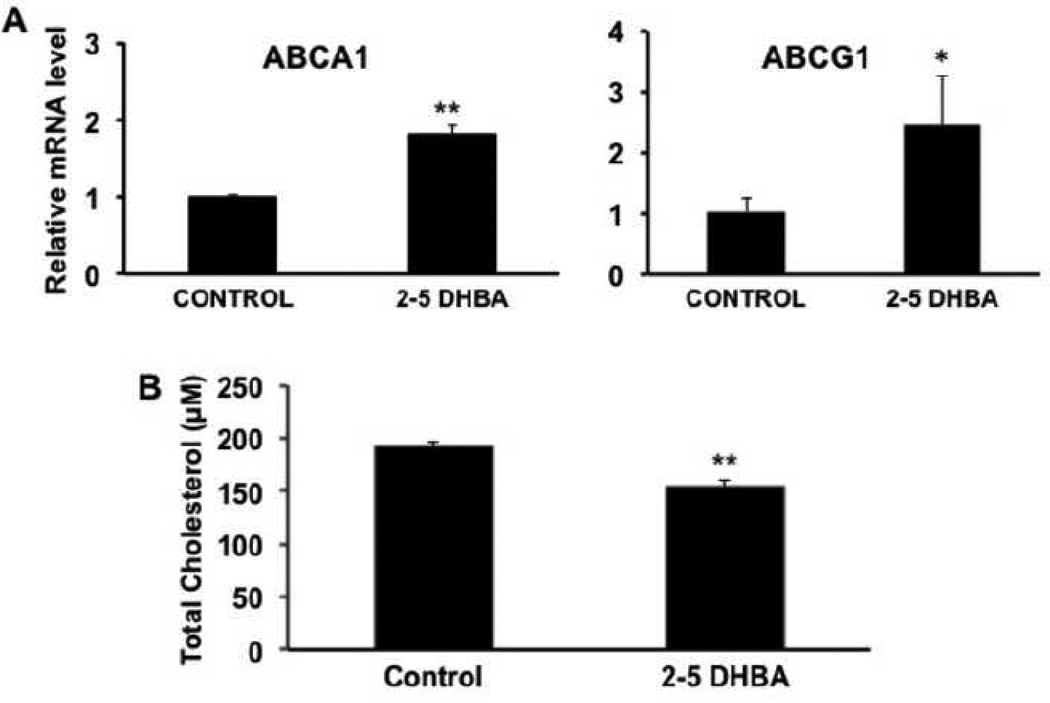

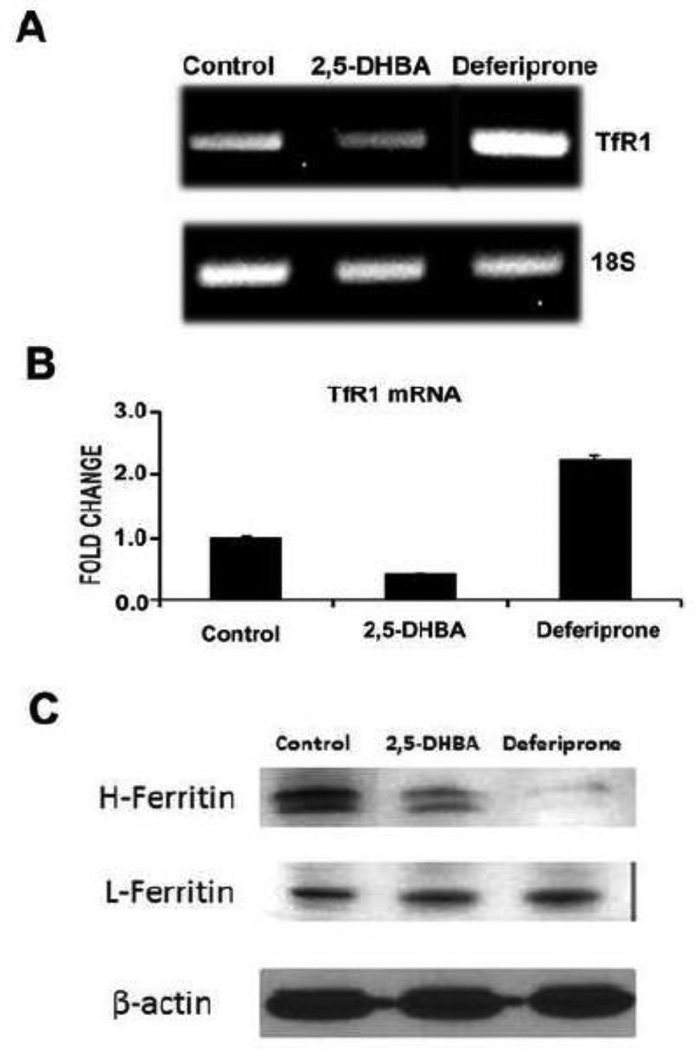

It has recently been shown that mammalian cells synthesize an endogenous siderophore (i.e., an iron carrier), known as 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,5-DHBA), which facilitates the transfer of iron across the plasma membrane as well as across the inner mitochondrial membrane [27]. Since the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in the retina is altered in the iron-overload disease hemochromatosis, we wondered whether treatment of RPE cells with the endogenous siderophore would have any effect on the expression of these transporters. To address this issue, we treated the human RPE cell line ARPE-19, a widely used model for RPE [41], with 2,5-DHBA for 16 h and then monitored the levels of ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNAs. These experiments showed that the expression of both transporters were upregulated significantly in the RPE cell line when treated with 2,5-DHBA (Fig. 5A). This was associated with a decrease in the cellular cholesterol content as expected from the known function of these transporters in the efflux of cholesterol from the cells (Fig. 5B). Since 2,5-DHBA is not simply an iron chelator but rather an iron carrier responsible for iron entry into the cell and also into the mitochondria, we asked whether the observed effects of this siderophore on the expression of the cholesterol efflux transporters is due to depletion of free iron. To address this question, we compared the influence of 2,5-DHBA with that of deferiprone, which functions simply as an iron chelator rather than as an iron carrier. ARPE-19 cells were treated with 250 µM of either 2,5-DHBA or deferiprone for 16 h and then the levels of TfR1 mRNA were measured by RT-PCR and qPCR and ferritin protein levels were measured by Western blot. Steady-state levels of TfR1 mRNA as well as H subunit of ferritin were decreased with 2,5-DHBA (Fig. 6). These data were unexpected; while the changes in H-ferritin suggest depletion of free iron, the changes in TfR1 mRNA suggest the opposite. This was in contrast with the findings that treatment of the cells with deferiprone increased the levels of TfR1 mRNA and decreased the levels of H-ferritin, which indicate that deferiprone does indeed deplete intracellular levels of free iron under similar conditions as expected of an iron chelator.

Fig. 5.

Influence of the endogenous iron chelator 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (2,5-DHBA) on the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 and cholesterol content in ARPE-19 cells. (A) The cells were treated with 250 µM 2,5-DHBA for 24 h and the levels of ABCA1 and ABCG1 mRNAs were then determined by real-time RT-PCR. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 compared to control by paired Student’s t test. (B) The cells were treated with 250 µM 2,5-DHBA for 24 h and the cellular levels of cholesterol were then determined. **, p < 0.01 compared to control by paired Student’s t test.

Fig. 6.

Influence of 2,5-DHBA (a siderophore) and deferiprone (an iron chelator) on the levels of TfR1 mRNA and ferritin protein (heavy chain H and light chain L) in RPE. The human RPE cell line ARPE-19 was exposed to 250 µM of either 2,5-DHBA or deferiprone for 16 h and then total RNA was isolated and protein extracts prepared. Untreated cells were used as the control. The changes in the steady-state levels of TfR1 mRNA were monitored by RT-PCR and qPCR (A & B) and those in ferritin (heavy chain H and light chain L) were monitored by Western blot (C).

3.6. Expression pattern of Bdh2, the enzyme critical for the biosynthesis of 2,5-DHBA, in the retina

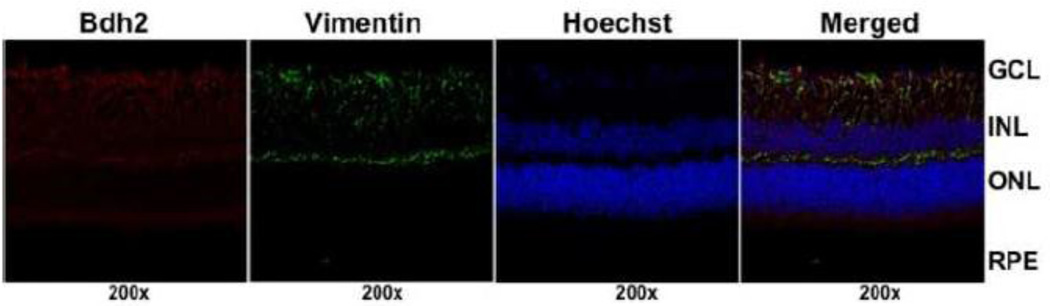

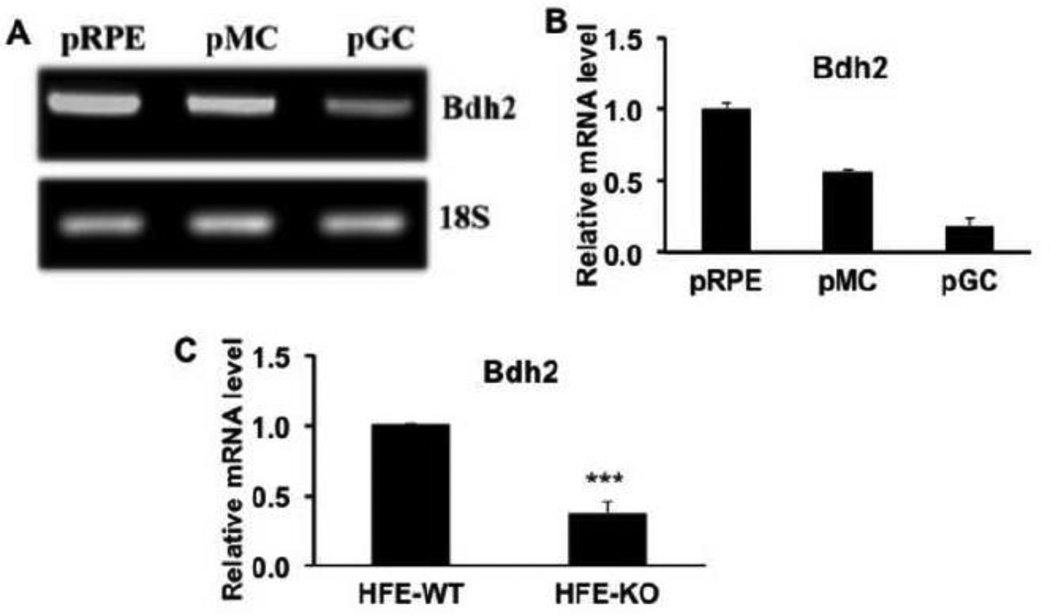

The enzyme that is critical for the synthesis of 2,5-DHBA in mammalian cells is β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase-2 (Bdh2) [27]. We examined the expression pattern of this enzyme in mouse retina. We found robust expression of the enzyme throughout the retina in all cell layers, including ganglion cells, Muller cells, and RPE cells (Fig. 7). The radial distribution pattern of the immune-positive signals in the retinal sections indicated the expression of the enzyme in Muller cells. This was confirmed by double-labeling with vimentin, a marker for retinal Muller cells. We used RNA isolated from primary mouse retinal ganglion cells, Muller cells, and RPE cells to determine the relative expression levels of this enzyme in the three retinal cell types (Fig. 8A, B). The expression in RPE was maximal, followed by Muller cells and then ganglion cells.

Fig. 7.

Expression pattern of Bdh2 in mouse retina. Mouse (Balb/c) frozen retinal sections were used for immunofluorescence to determine the expression pattern of Bdh2 (red fluorescence signals). Vimentin (green fluorescence signals) was used as a marker for Muller cells and Hoechst stain (blue fluorescence signals) for nuclei. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

Fig. 8.

Relative expression of Bdh2 in primary cultures of mouse retinal ganglion cells, Muller cells, and RPE cells and retinal expression of Bdh2 in wild type (HFE-WT) and Hfe−/− (HFE-KO) mice. (A) RT-PCR analysis of Bdh2 mRNA levels in primary cultures of mouse RPE cells (pRPE), Muller cells (pMC), and ganglion cells (pGC). 18S mRNA was used as an internal control. (B) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of relative levels of Bdh2 mRNA in primary cultures of mouse RPE cells (pRPE), Muller cells (pMC), and ganglion cells (pGC). The mRNA level in pRPE was taken as 1. (C) Comparison of Bdh2 mRNA in retinas from age-matched (18-month-old) wild type and Hfe−/− mice as monitored by real-time RT-PCR. ***, p < 0.001 compared to wild type control by paired Student’s t test.

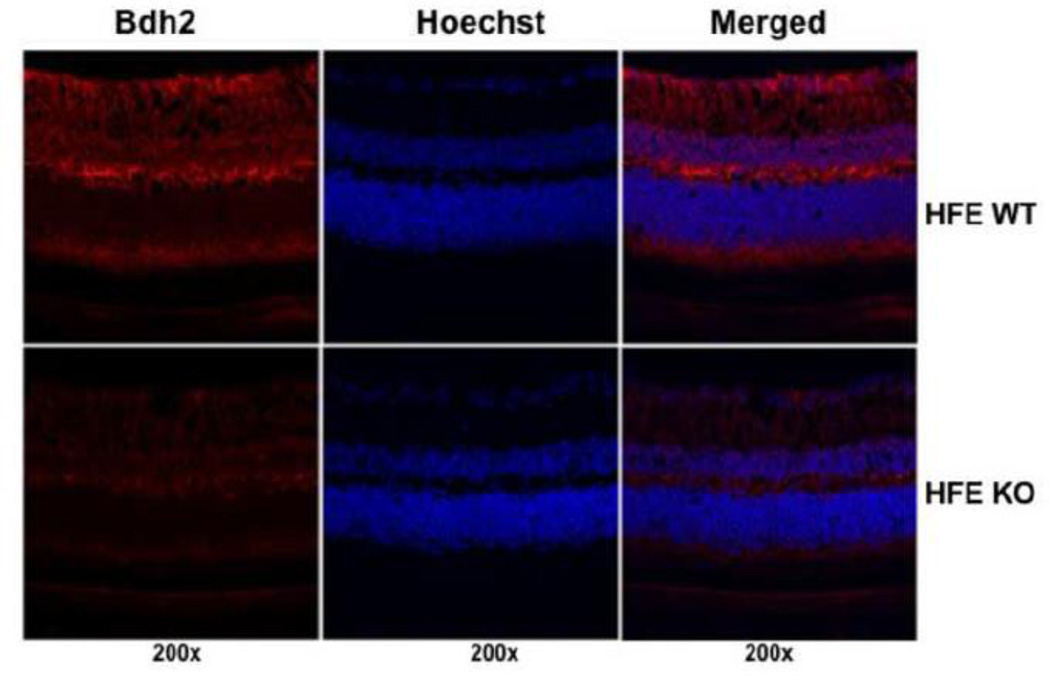

3.7. Regulation of Bdh2 expression in the retina in hemochromatosis

Since 2,5-DHBA as a siderophore is a critical component of iron homeostasis in mammalian cells, we wondered whether the synthesis of this compound is altered in the iron-overload disease hemochromatosis. To address this issue, we examined the expression of Bdh2 in wild type mouse retina and Hfe−/− mouse retina. We found marked reduction in Bdh2 mRNA levels in hemochromatosis retinas compared to wild type retinas (Fig. 8C). This was also evident at the protein level (Fig. 9). The decrease in Bdh2 expression observed in Hfe−/− mouse retina was evident in all cell layers.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of Bdh2 protein expression in the retina between wild type (HFE WT) and Hfe−/− (HFE KO) mice. Bdh2 protein expression was monitored in frozen retinal sections by immunofluorescence (red fluorescence signals) with Hoechst stain (blue fluorescence signals) to visualize nuclei. Age-matched (18-month-old) mice were used.

4. Discussion

The most salient findings of the present study can be summarized as follows: (a) the cholesterol efflux transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 are expressed in three important cell types in the retina, namely the ganglion cells, Muller cells, and RPE cells; (b) the expression of both transporters is downregulated to a significant extent in the iron-overload disease hemochromatosis, and the decrease in the expression is evident in all three cell types (RPE, Muller cells, and ganglion cells); (c) the disease-associated silencing of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in the retina occurs most likely via epigenetic mechanism involving DNA methylation; (d) the decrease in the expression of the two transporters in hemochromatosis mouse retina is associated with an increase in cholesterol content in the tissue; (e) treatment of the RPE cell line ARPE-19 with the recently discovered endogenous siderophore 2,5-DHBA enhances the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 with resultant decrease in cellular content of cholesterol; (f) the mouse retina and several important retinal cell types (ganglion cells, Muller cells, and RPE cells) express Bdh2, which is the critical rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of 2,5-DHBA; and (g) the expression of this enzyme is downregulated in hemochromatosis mouse retina.

The findings of this study are significant for several reasons. These have relevance to retinal biology both in health and disease states. Cholesterol is an important component of cell membranes, not only as a structural constituent but also as a modulator of membrane permeability, and the state and function of microdomains such as the lipid rafts, which are critical for the transmission of intracellular signals from various cell-surface receptors. Therefore, it is essential to understand how the cellular and tissue content of cholesterol is regulated in the retina. ABCA1 and ABCG1 represent two important transporters that mediate the ATP-coupled efflux of cholesterol from the cells. There is some evidence in the literature for the expression of ABCA1 in the retina. Duncan et al. [42] and Simon et al. [43] have shown that ABCA1 is expressed in the retina and RPE cells. The study by Duncan et al. [42] has demonstrated the expression of ABCA1 protein in the inner segment of photoreceptor cells by immunofluorescence analysis and in the basolateral membrane of RPE cells by functional analysis. Our studies not only confirm these earlier observations but also provide new evidence for the presence of ABCA1 in the apical membrane of RPE cells. The expression of ABCG1 has never been studied in the retina, and the present study is the first to demonstrate the expression of this cholesterol efflux transporter in the retina and retinal cell types. Even though the retinal expression pattern of the two transporters is similar for most part, which includes expression in several important cell types (ganglion cells, Muller cells, and RPE cells) and presence in the apical as well as basolateral membrane of RPE cells, the two transporters differ in one important aspect. While ABCA1 is expressed in the inner segment of the photoreceptor cells, ABCG1 is restricted to the outer segment.

The functional significance of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in RPE is readily apparent, particularly the findings that the transporters are expressed more robustly in the apical membrane than in the basolateral membrane. RPE cells handle a large load of cholesterol arising from phagocytosis of the outer segments of photoreceptor cells; as such, RPE cells must possess transport mechanisms to remove cholesterol as a means to prevent excessive accumulation of this lipid inside the cells. ABCA1 and ABCG1 are likely to serve this important role. The quantitatively more robust expression of both transporters in the apical membrane of RPE cells underlines the essential function of this cell in supplying cholesterol to the neural retina. We speculate that the photoreceptor-derived cholesterol in RPE cells following phagocytosis is not only removed from the retina via ABCA1 and ABCG1 in the basolateral membrane but is also effluxed into neural retina via ABCA1 and ABCG1 in the apical membrane for re-use by the photoreceptor cells. The supply of cholesterol to the neural retina may not be the only function of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in the apical membrane of RPE cells. There is evidence suggesting an essential role for ABCA1 in delivering the dietary lipids lutein and zeaxanthin to the retina [44, 45]. Defects in the function of this transporter are associated with a significant decrease in retinal levels of these lipids. Therefore, in addition to the role in the re-circulation of cholesterol between photoreceptor cells and RPE cells, the apically located ABCA1 and ABCG1 in RPE cells may also function in the supply of lutein and zeaxanthin to neural retina.

Polymorphisms in ABCA1 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AMD [46–49]. However, a major part of the effort to explain the link between defective ABCA1 and AMD at the functional level has focused on the relevance of this transporter to reverse-cholesterol transport in mediating cholesterol efflux from macrophages to load it on high-density lipoprotein (HDL). A recent study has shown that senescent macrophages exhibit decreased expression and activity of ABCA1 and that the resultant accumulation of cholesterol within the aged macrophages polarizes these cells to an abnormal phenotype that promotes pathologic vascular proliferation [50]. Deletion of Abca1 selectively in macrophages mimics the phenotype of senescent macrophages. In contrast, disruption of cholesterol homeostasis in retinal cells such as RPE as a potential contributor to the pathogenesis of AMD has received less attention. Our present studies reporting on the robust widespread expression of the cholesterol efflux transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 in the retina are likely to form the basis for future research focusing on the potential role of altered cholesterol homeostasis within retinal cells in the pathogenesis of AMD. There is strong evidence supporting a pathogenic role of excessive cholesterol in AMD [23–26]; therefore, defects in the function of the two cholesterol efflux transporters examined in the present study are expected to disrupt cholesterol homeostasis in the retina and hence may contribute to the progression of AMD.

The present studies also report for the first time on the association between the genetic disease hemochromatosis and cholesterol accumulation within the retina and RPE. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies in the literature indicating any role for iron in the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Our studies show that iron is an important regulator of retinal cholesterol levels in health and disease. Hemochromatosis is a disease of iron overload in systemic organs as well as in retina. The present findings that excessive iron in the retina in a mouse model of hemochromatosis disrupts cholesterol homeostasis through downregulation of the cholesterol efflux transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 are interesting because of the increasing evidence for the involvement of excessive iron in the progression of AMD. The mechanism underlying the decrease in ABCA1 and ABCG1 expression in hemochromatosis mouse retina involves DNA methylation. Even though our previous studies showing an increase in the expression of DNA methyltransferases in hemochromatosis mouse RPE cells [40] offer a molecular mechanism for the silencing of the two cholesterol efflux transporters, how excessive iron increases the expression of DNMTs is not known. Nonetheless, the importance of the findings to retinal cholesterol homeostasis as well as AMD is clear. The prevalence of hemochromatosis is very high in general population. Interestingly, even though this is a genetic disease, the appearance of clinical complications is age-dependent. In patients with this disease, it takes decades for iron to accumulate in tissues to pathogenic levels, precipitating clinical symptoms. This is true not only for the pathological symptoms associated with systemic organs but also for the biochemical and morphological changes associated with the retina. Given the similarities between the appearance of pathological complications in hemochromatosis and AMD in terms of age-dependence, we speculate that hemochromatosis may contribute to the progression of AMD through excessive iron. Accumulation of iron in tissues to abnormally high levels is known to cause oxidative damage, which could be a contributing factor in the progression of AMD. The findings of the present study linking excessive iron to disruption of cholesterol homeostasis in the retina offer an additional, but hitherto unknown, potential molecular link between hemochromatosis and AMD.

Deletion of Hfe in mice leads to significant biochemical and morphological alterations in the retina [15, 36, 37]. Some of these changes are similar to those found in AMD. To what extent these similarities in retinal features seen in hemochromatosis and AMD can be explained in terms of the changes in retinal cholesterol content is not known. The retinal pathology begins to appear in hemochromatosis mice only at >18 months of age [15, 36]. It would be interesting to determine if the progression of the retinal pathology is accelerated in Hfe−/−/Abca1−/− mice or Hfe−/−/Abcg1−/− mice.

Another important observation of the present study is the evidence that the retina expresses the enzyme Bdh2 that is critical for the synthesis of the endogenous siderophore 2,5-DHBA, that the expression of this iron-regulatory enzyme is altered in the retina in the iron-overload disease hemochromatosis, and that the newly discovered siderophore 2,5-DHBA regulates cholesterol homeostasis in RPE. The expression of the enzyme is highest in RPE, much higher than in Muller cells and ganglion cells. These findings suggest that RPE and other cell types in the retina are capable of synthesizing 2,5-DHBA, Being a siderophore, this compound is likely to play a critical role in the biology of iron in the retina, particularly with regard to subcellular distribution of iron in the cytoplasm versus mitochondria due to the function of this compound as a carrier of iron across the plasma membrane and the inner mitochondrial membrane [27]. It is quite intriguing to note that so many genes have already been identified as key players in iron homeostasis and that loss-of-function mutations in five different genes can lead to the iron-overload disease hemochromatosis. BDH2 represents the newest addition to the already known plethora of genes that control iron homeostasis. The function of iron as a regulator of cholesterol homeostasis in RPE is evident from the present findings that exposure of RPE cells to the endogenous siderophore 2,5-DHBA influences the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1. Interestingly, the effect of 2,5-DHBA on the steady-state levels of TfR1 mRNA is different from that of the iron chelator deferiprone, suggesting that the consequences of 2,5-DHBA-induced perturbation in subcellular distribution of iron inside the cell are not the same as those of a global decrease in intracellular levels of free iron caused by an iron chelator. However, 2,5-DHBA and deferiprone had similar effects on the cellular levels of H-ferritin. There is no information in the literature as to how changes in subcellular distribution of iron inside the cell influences TfR1 mRNA and ferritin protein levels. The results presented here are the first to describe the influence of the endogenous siderophore 2,5-DHBA on TfR1 mRNA and ferritin levels. Equally interesting are the observations that the retinal expression of Bdh2 is downregulated in hemochromatosis. This has significant implications in the pathology of the disease because impaired synthesis of the endogenous siderophore is expected to decrease the delivery of iron to the mitochondria. Since excessive iron in mitochondria is toxic to the cell, it is likely that the downregulation of the synthesis of this siderophore in hemochromatosis represents a compensatory mechanism to blunt the toxic effects of excessive iron accumulation associated with the disease. A recent study has demonstrated the downregulation of BDH2 in the liver of patients with hemochromatosis [51]. Ours is the first report on the expression of this enzyme in normal retina and on the suppression of its expression in hemochromatosis, thus providing another important link between hemochromatosis and retinal pathology, particularly AMD.

Highlights.

Cholesterol efflux transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 are expressed in mouse retina

Retinal expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 is downregulated in hemochromatosis mouse

Retinal cholesterol content is elevated in hemochromatosis mouse

2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid, a siderophore, increases ABCA1/ABCG1 expression

Synthesis of 2,5-dihodroxybenzoic acid is decreased in hemochromatosis mouse retina

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant EY 019672.

Abbreviations used

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- ABCA1

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

- ABCG1

ATP-binding cassette transporter G1

- Bdh2

β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase-2

- 2,5-DHBA

2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid

- AMD

age-related macular degeneration

- pRPE

primary cultures of mouse retinal pigment epithelial cells

- pMC

primary cultures of mouse Muller cells

- pGC

primary cultures of mouse retinal ganglion cells

- 5-Aza-C

5-azacytidine

- TfR

transferrin receptor

- HAMP

hepatic anti-microbial peptide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest, and that they have no financial interest in the information contained in the present manuscript.

References

- 1.Cai X, McGinnes JF. Oxidative stress: the achilles’ heel of neurodegenerative diseases of the retina. Front. Biosci. 2012;17:1976–1995. doi: 10.2741/4033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarrett SG, Boulton ME. Consequences of oxidative stress in age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Aspects Med. 2012;33:399–417. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambati J, Atkinson JP, Gelfand BD. Immunology of age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:438–451. doi: 10.1038/nri3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambati J, Fowler BJ. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration. Neuron. 2012;75:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pennesi ME, Neuringer M, Courtney RJ. Animal models of age related macular degeneration. Mol. Aspects Med. 2012;33:487–509. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He X, Hahn P, Iacovelli J, Wong R, King C, Bhisitkul R, Massaro-Giordano M, Dunaief JL. Iron homeostasis and toxicity in retinal degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2007;26:649–673. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blasiak J, Szaflik J, Szaflik JP. Implications of altered iron homeostasis for age-related macular degeneration. Front. Biosci. 2011;16:1551–1559. doi: 10.2741/3804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song D, Dunaief JL. Retinal iron homeostasis in health and disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:24. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gnana-Prakasam JP, Martin PM, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Expression and function of iron-regulatory proteins in retina. IUBMB Life. 2010;62:363–370. doi: 10.1002/iub.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babitt JL, Lin HY. The molecular pathogenesis of hereditary hemochromatosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 2011;31:280–292. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pietrangelo A, Caleffi A, Corradini E. Non-HFE hepatic iron overload. Semin. Liver Dis. 2011;31:302–318. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan J, Ward DM, De Domenico I. The molecular basis of iron overload disorders and iron-linked anemias. Int. J. Hematol. 2011;93:14–20. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0760-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganz T, Nemeth E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1823:1434–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nander W, Connor JR. HFE gene variants affect iron in the brain. J. Nutr. 2011;141:729S–739S. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.130351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnana-Prakasam JP, Thangaraju M, Liu K, Ha Y, Martin PM, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Absence of iron-regulatory protein Hfe results in hyperproliferation of retinal pigment epithelium: role of cystine/glutamate exchanger. Biochem. J. 2009;424:243–252. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadziahmetovic M, Song Y, Ponnuru P, Iacovelli J, Hunter A, Haddad N, Beard J, Connor JR, Vaulont S, Dunaief JL. Age-dependent retinal iron accumulation and degeneration in hepcidin knockout mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:109–118. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gnana-Prakasam JP, Tawfik A, Romej M, Ananth S, Martin PM, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Iron-mediated retinal degeneration in haemojuvelin-knockout mice. Biochem. J. 2012;441:599–608. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montero-Vega MT. The inflammatory process underlying atherosclerosis. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2012;32:373–462. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v32.i5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorci-Thomas MG, Thomas MJ. High density lipoprotein biogenesis, cholesterol efflux, and immune cell function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:2561–2565. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norata GD, Pirillo A, Catapano AL. HDLs, immunity, and atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2011;22:410–416. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32834adac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yvan-Charvet L, Wang N, Tall AR. Role of HDL, ABCA1, and ABCG1 transporters in cholesterol efflux and immune responses. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30:139–143. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye D, Lammers B, Zhao Y, Meurs I, Van Berkel TJ, Van Eck M. ATP-binding cassette transporters A1 and G1, HDL metabolism, cholesterol efflux, and inflammation: important targets for treatment of atherosclerosis. Curr. Drug Targets. 2011;12:647–660. doi: 10.2174/138945011795378522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dithmar S, Curcio CA, Le NA, Brown S, Grossniklaus HE. Ultrastructural changes in Bruch’s membrane of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:2035–2042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudolf M, Winkler B, Aherrahou Z, Doehring LC, Kaczmarek P, Schmidt-Erfurth U. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor associated with accumulation of lipids in Bruch’s membrane of LDL receptor knockout mice. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1627–1630. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.071183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu W, Jiang A, Liang J, Meng H, Chang B, Gao H, Qiao X. Expression of VLDLR in the retina and evolution of subretinal neovascularization in the knockout mouse model’s retinal angiomatous proliferation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008;49:407–415. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujihara M, Bartels E, Nielsen LB, Handa JT. A human apoB100 transgenic mouse expresses human apoB100 in the RPE and develops features of early AMD. Exp. Eye Res. 2009;88:1115–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davireddy LR, Hart DO, Goetz DH, Green MR. A mammalian siderophore synthesized by an enzyme with a bacterial homolog involved in enterobactin production. Cell. 2010;141:1006–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hicks D, Courtois Y. The growth and behaviour of rat retinal Müller cells in vitro. 1. An improved method for isolation and culture. Exp. Eye Res. 1990;51:119–129. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(90)90063-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umapathy NS, Li W, Mysona BA, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Expression and function of glutamine transporters SN1 (SNAT3) and SN2 (SNAT5) in retinal Müller cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:3980–3987. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barres BA, Silverstein BE, Corey DP, Chun LL. Immunological, morphological, and electrophysiological variation among retinal ganglion cells purified by panning. Neuron. 1988;1:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dun Y, Mysona B, Van Ells T, Amarnath L, Ola MS, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Expression of the cystine-glutamate exchanger (x−c) in retinal ganglion cells and regulation by nitric oxide and oxidative stress. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;324:189–202. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganapathy PS, White RE, Ha Y, Bozard BR, McNeil PL, Caldwell RW, Kumar S, Black SM, Smith SB. The role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation in homocysteine-induced death of retinal ganglion cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:5515–5524. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Philp NJ, Wang D, Yoon H, Hjelmeland LM. Polarized expression of monocarboxylate transporters in human retinal pigment epithelium and ARPE-19 cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003;44:1716–1721. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin PM, Gnana-Prakasam JP, Roon P, Smith RG, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Expression and polarized localization of the hemochromatosis gene product HFE in retinal pigment epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:4238–4244. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gnana-Prakasam JP, Zhang M, Martin PM, Atherton SS, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Expression of the iron-regulatory protein haemojuvelin in retina and its regulation during cytomegalovirus infection. Biochem. J. 2009;419:533–543. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gnana-Prakasam JP, Ananth S, Prasad PD, Zhang M, Atherton SS, Martin PM, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Expression and iron-dependent regulation of succinate receptor GPR91 in retinal pigment epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:3751–3758. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gnana-Prakasam JP, Reddy SK, Veeranan-Karmegam R, Smith SB, Martin PM, Ganapathy V. Polarized distribution of heme transporters in retinal pigment epithelium and their regulation in the iron-overload disease hemochromatosis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:9279–9286. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guay SP, Brisson D, Munger J, Lamarche B, Gaudet D, Bouchard L. ABCA1 gene promoter DNA methylation is associated with HDL particle profile and coronary artery disease in familial hypercholesterolemia. Epigenetics. 2012;7:464–472. doi: 10.4161/epi.19633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee BH, Taylor MG, Robinet P, Smith JD, Schweitzer J, Sehayek E, Falzarano SM, Magi-Galluzzi C, Klein EA, Ting AH. Dysregulation of cholesterol homeostasis in human prostate cancer through loss of ABCA1. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1211–1218. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gnana-Prakasam JP, Veeranan-Karmegam R, Coothankandaswamy V, Reddy SK, Martin PM, Thangaraju M, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Loss of Hfe leads to progression of tumor phenotype in primary retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013;54:63–71. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dunn KC, Aotaki-Keen AE, Pulkey FR, Hjelmeland LM. ARPE-19, a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line with differentiated properties. Exp. Eye Res. 1996;62:155–169. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duncan KG, Hosseini K, Bailey KR, Yang H, Lowe RJ, Matthes MT, Kane JP, LaVail MM, Schwartz DM, Duncan JL. Expression of reverse cholesterol transport proteins ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1) and scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI) in the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2009;93:1116–1120. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.144006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon E, Bardet B, Gregoire S, Acar N, Bron AM, Creuzot-Garcher CP, Bretillon L. Decreasing dietary linoleic acid promotes long chain omega-3 fatty acid incorporation into rat retina and modifies gene expression. Exp. Eye Res. 2011;93:628–635. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conner WE, Duell PB, Kean R, Wang Y. The prime role of HDL to transport lutein into the retina: evidence from HDL-deficient WHAM chicks having a mutant ABCA1 transporter. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007;48:4226–4231. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yonova-Doing E, Hysi PG, Venturini C, Williams KM, Nag A, Beatty S, Liew SH, Gilbert CE, Hammond CJ. Candidate gene study of macular response to supplemental lutein and zeaxanthin. Exp. Eye Res. 2013;115:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zareparsi S, Buraczynska M, Branham KE, Shah S, Eng D, Li M, Pawar H, Yashar BM, Moroi SE, Lichter PR, Petty HR, Richards JE, Abecasis GR, Elner VM, Swaroop A. Toll-like receptor 4 variant D299G is associated with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:1449–1455. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen W, Stambolian D, Edwards AO, Branham KE, Othman M, et al. Genetic variants near TIMP3 and high-density lipoprotein-associated loci influence susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:7401–7406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912702107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peter I, Huggins GS, Ordovas JM, Haan M, Seddon JM. Evaluation of new and established age-related macular degeneration susceptibility genes in the Women’s Health Initiative Sight Exam (WHI-SE) Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2011;152:1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu Y, Reynolds R, Rosner B, Daly MJ, Seddon JM. Prospective assessment of genetic effects on progression to different stages of age-related macular degeneration using multistate Markov models. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012;53:1548–1556. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sene A, Khan AA, Cox D, Nakamura REI, Santeford A, Kim BM, Sidhu R, Onken MD, Harbour JW, Hagbi-Levi S, Chowers I, Edwards PA, Baldan A, Parks JS, Ory DS, Apte RS. Impaired cholesterol efflux in senescent macrophages promotes age-related macular degeneration. Cell Metab. 2013;17:549–561. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Z, Lanford R, Mueller S, Gerhard GS, Luscieti S, Sanchez M, Devireddy L. Siderophore-mediated iron trafficking in humans is regulated by iron. J. Mol. Med. 2012;90:1209–1221. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0899-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]