Abstract

Primary primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) are extremely rare in the lung and especially in adult women. We describe a case of PNET of the lung with aggressive behavior in 31-year-old woman. Diagnosis was based on histopathological and immunohistochemical studies, and confirmed by molecular genetic analysis of chromosome rearrangements in the EWSR1 gene region. Clinical follow-up, post-mortem findings, and differential diagnosis are also discussed.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/1477-7819-12-374) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Primitive neuroectodermal tumor, Ewing’s sarcoma, Lung, Differential diagnosis

Background

Primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) are small-blue-round-cell malignancies, predominantly arising in the soft tissues or bones in children and young adults [1]. PNETs belong to the Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors, based on shared chromosomal translocation at EWSR1 (Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1). Primary PNETs of the lung are extremely rare, with fewer than 20 cases having been described in English literature to date. Most of these are adolescent or young adult patients, with a male predominance [2–13]. In this case report, we describe a PNET of lung in an adult woman, having a rapid progression of the disease and lethal outcome.

Case presentation

A 31-year-old woman presented with a 10-month history of right hemithoracic pain and persistent cough, with relative improvement during the day and relative worsening at night. She also reported a weight loss of approximately 11 kg. Computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of the thorax revealed non-homogeneous opacities and increased accumulation of glucose in the right pleural cavity. Right pleural deposits, found during examination, suggested the presence of viable tumor masses. Directed transparietal biopsy, taken from the glucose accumulation sites seen on the PET scan, was performed.

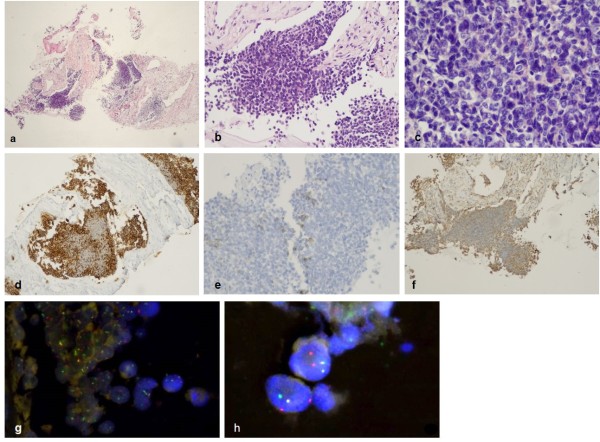

Histopathological examination of the biopsy specimens revealed highly cellular neoplastic tissue. The tumor cells were discohesive, showed scant basophilic cytoplasm, and ovoid rather than polygonal nuclei, fine granular chromatin texture, and marked nucleoli. Some of the nuclei were hyperchromatic. There were no evidence of mitotic or apoptotic activity. No obvious signs of necrosis were present, and the stromal tissue adjacent to the tumor was characterized by low cellularity. In some areas, small Homer-Wright rosette-like structures were present. Overall, morphological characteristics were consistent with small-blue-round-cell neoplasm (Figure 1a, b ,c).

Figure 1.

Biopsy specimen from primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) of the lung. (a) Areas of highly cellular neoplastic tissue (H&E, magnification × 40), (b) discohesive growth of small, blue, round to oval cells, characteristic of pulmonary PNET (H&E, magnification × 200). (c) Characteristic scant, basophilic cytoplasm, ovoid or polygonal nuclei, fine granular chromatin texture and marked nucleoli. Some nuclei were hyperchromatic. H&E, magnification × 400. d) CD99 membranous expression, characteristic of PNET (magnification × 100). and expression of (e) CD56 (magnification × 100) and (f) vimentin (magnification × 100). (g, h) Fluorescent in situ hybridization of EWSR1 gene: fusion signals: yellow or red/green double spot indicates intact EWSR1, separate green and red signals indicate translocation. Magnification (g) × 600, (h) × 1000).

A range of immunohistochemical markers were employed for final diagnosis (Table 1), including CD4, CD8, CD10, CD15, CD20, CD34, leukocyte common antigen (CD45), CD56, CD99, cytokeratin 7 (CK7), vimentin, thyroid transcription factor (TTF), synaptophysin, chromogranin, anti-cytokeratin cocktail, High Molecular weight cytokeratin,, calretinin, h-caldesmon, smooth muscle actin (SMA) and mesothelial cell marker (antibody clone: HBME-1). Detailed characteristics and dilutions of antibodies are provided in Additional file 1: Table S1. Immunohistochemical study showed Strong positivity for CD99 (Figure 1d). The neoplastic cells were also focally positive for CD56 and weekly positive for Vimentin (Figure 1e, f). Expression of TTF was extremely weak. All other markers were negative. Proliferative activity, detected by Ki-67 index, was estimated as 5 to 10%. Immunophenotype was characteristic for PNET of the lung.

Table 1.

Differential diagnostic markers of small-blue- round-cell tumors in lung

| IHC markers | CD99 | CD56 | Vim | TTF | Syn | Chr | CD34 | LCA (CD45) | CD10 | CD15 | CK7 | AE1/AE3 | CK(HMW) | Calret | h-Cal | Desmin | SMA | HBME-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor types | ||||||||||||||||||

| PNET | ++ | +/- | + | - | +/- | - | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of lung | - | - | ++ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ++ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Small cell carcinoma of the lung | - | + | - | ++ | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | ++ | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| Lung carcinoid | - | - | - | + | ++ | ++ | - | - | - | - | - | ++ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Metastasis of small cell carcinomas of other origin | - | +/- | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pulmonary rhabdomyosarcoma | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | - |

| NHL | +/- | - | - | - | - | - | - | ++ | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Calret, calretinin; Chr, chromogranin; CK7, cytokeratin 7; CK(HMW), high molecular weight cytokeratin; HBME-1 – mesothelial cell marker; h-Cal, h-caldesmon; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LCA, leukocyte common antigen; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; PNET, primitive neoroectodermal tumor; SMA, smooth muscle actin; Syn, Synaphtophysin; TTF, thyroid transcription factor; Vim, vimentin.

Chromosome rearrangement in the EWSR1 gene was detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization assay (FISH) to confirm the diagnosis. The results of FISH analysis showed translocation of EWSR1 in 30% of the tumor cells (Figure 1g, h). More detailed description of molecular analysis in provided in Additional file 1: S2.

Diagnosis was followed by two series of chemotherapy (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and vincristine) for 2 days. After 1 month, secondary anemia developed. The patient was treated with hemosubstitution, but her health deteriorated and she died. Post-mortem examination revealed a tumor in the right lung, 210 × 115 × 60 mm in size. The cut surface of the tumor was pinkish colored and areas of hemorrhage were present. Post-mortem and subsequent histopathological examination showed generalized PNET, (Additional file 1: Figure S1), with tumor spread to the mediastinal lymph nodes and subhepatic area. Acute catarrhal purulent bronchopneumonia was present in the left lung. The cause of death was given as cardiorespiratory failure.

Discussion

PNETs are highly aggressive, usually lethal neoplasms. Although the morphological and immunohistochemical features of pulmonary PNET are not different from its counterparts of other origin, special diagnostic considerations of other tumors with small, blue, round cell morphology and primarily small cell carcinoma of the lung is necessary. Small cell carcinomas usually present at older ages, and usually with a history of smoking, yet they and PNET may exhibit similar histological features. Some PNETs may even show reactivity for cytokeratin and synaptophysin [11, 12]. Hence, a wider range of immunohistochemical markers, including chromogranin and TTF-1 to support a diagnosis of small cell carcinoma, and CD99, vimentin, or FLI1 for PNET should be used for the differential diagnosis. Lung carcinoids share a similar morphology to PNET and form rosettes. However, the detection of chromogranin, synaphtopysin, and neuron specific enolase is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of lung carcinoid. In addition, differential diagnosis is necessary to distinguish PNET from metastasis of small cell carcinomas of other origin. Another important diagnostic consideration for both children and adult patients is pulmonary rhabdomyosarcoma, which is also a rare tumor and belongs to the group of small,-blue,-round-cell tumors. Muscle-specific markers such as desmin, myogenin, or myo-D1, characteristic of rhabdomyosarcoma, should be included in the immunohistochemical study [10]. Lymphoblastic lymphoma and the leukemia group of tumors are also an important diagnostic consideration, as they can be positive for CD99 and negative for epithelial markers. Precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma is an especially important mimicker of PNET. Like PNET, the malignant cells are small and uniform and have a diffusely infiltrative growth pattern, and they can even form rosette-like structures. Immunohistochemically, precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma is positive for CD99, and often nonreactive or only focally positive for conventional lymphoma markers such as LCA, CD20, and CD3. Immunopositivity for CD45, CD43, and CD79a are useful for separating lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia from PNET [14]. Finally, to confirm the diagnosis of PNET, it is crucial to detect pass break or amplification of EWSR1 [15]. However, because of the rarity of primary pulmonary PNETs, it is also important to exclude the possibility of metastasis from a bone or soft tissue primary to the lung. Detailed examination by clinical and radiological means should be performed to rule out metastatic tumor from an extrapulmonary primary site.

Conclusion

Pulmonary PNET should be considered in the differential diagnosis of thoracic tumors, regardless of the age and sex of the patient. Although not specific, CD99 and vimentin are important immunohistochemical markers for diagnosis of PNET. However, a wider range of antibodies should be employed in order to exclude other diagnostic possibilities. Detection of EWSR1 gene translocation or amplification is the most reliable marker of PNET, including those of pulmonary origin.

Consent

Oral informed consent was obtained from the responsible person for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images.

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: Supplementary materials. (PDF 256 KB)

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by grants NT/13569 from the Czech Ministry of Health and NPU I LO1304 from the Czech Ministry of Education. MG was also supported by student's grant LF_2014_003.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JS, TT, PF, PL, JE evaluated biopsy specimens, chose the panel of antibodies for immunohistochemical study, evaluated the staining and made final agreed report. JS and MG performed the post-mortem examination. MG analyzed previous published data and wrote the manuscript. MI made corrections in written manuscript and assist to write the discussion, particularly the differential diagnostic considerations of PNET. RT performed fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of EWSR1. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Mariam Gachechiladze, Email: marjammg@gmail.com.

Josef Škarda, jojos@email.cz.

Maha Ibrahim, Email: MAI350@student.bham.ac.uk.

Tomáš Tichý, Email: tomas.tichy@fnol.cz.

Patrik Flodr, Email: flodrpatrik@seznam.cz.

Pavla Latálová, Email: latalova.pavla@seznam.cz.

Jiří Ehrmann, Email: jiri.ehrmann@hotmail.com.

Radek Trojanec, Email: radek.trojanec@seznam.cz.

Zdenek Kolář, Email: kolarz@tunw.upol.cz.

References

- 1.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Primitive neuroectodermal tumors and related lesions. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Soft Tissue Tumors. 5. Maryland Heights: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. pp. 945–987. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsuji S, Hisaoka M, Morimitsu Y, Hashimoto H, Jimi A, Watanabe J, Eguchi H, Kaneko Y. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the lung: report of two cases. Histopathology. 1998;33:369–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imamura F, Funakoshi T, Nakamura S, Mano M, Kodama K, Horai T. Primary primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the lung: report of two cases. Lung Cancer. 2000;27:55–604. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(99)00078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumgartner FJ, Omari BO, French SW. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the pulmonary hilum in an adult. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:285–287. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(00)02535-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahn AG, Avagnina A, Nazar J, Elsner B. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:397–399. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0397-PNTOTL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikami Y, Nakajima M, Hashimoto H, Irei I, Matsushima T, Kawabata S, Manabe T. Primary pulmonary primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET). A case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2001;197:113–119. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi D, Nagayama J, Nagatoshi Y, Inagaki J, Nishiyama K, Yokoyama R, Moriyasu Y, Okada K, Okamura J. Primary Ewing’s sarcoma family tumors of the lung: a case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;l37:874–877. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demir A, Dagoglu N, Gunluoglu MZ, Turna A, Dizdar Y, Kaynak K, Dilege S, Mandel NM, Yilmazbayhan D, Dincer SI, Gurses A. Surgical treatment and prognosis of primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the thorax. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;l4:185–192. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318194fafe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hancorn K, Sharma A, Shackcloth M. Primary extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma of the lung. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;10:803–804. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.216952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissferdt A, Moran CA. Primary pulmonary primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET): a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of six cases. Lung. 2012;190(6):677–683. doi: 10.1007/s00408-012-9405-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tongaonkar HB, Thyavihally YB, Gupta S, Kurkure PA, Amare P, Muckaden MA, Desai SB. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the kidney: a single institute series of 16 patients. Urology. 2008;71:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charney DA, Ghali VS, Charney JM, Teplitz C. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the myocardium: a case report, review of the literature, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:1365–1369. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(96)90352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Askin FB, Rosai J, Sibley RK, Dehner LP, McAlister WH. Malignant small cell tumor of the thoracopulmonary region in childhood: a distinctive clinicopathologic entity of uncertain histogenesis. Cancer. 1979;43:2438–2451. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197906)43:6<2438::AID-CNCR2820430640>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucas DR, Bentley G, Dan ME, Tabaczka P, Janet M, Poulik JM, Michael MP. Ewing sarcoma vs lymphoblastic lymphoma a comparative immunohistochemical study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115:11–17. doi: 10.1309/K1XJ-6CXR-BQQU-V255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gamberi G, Cocchi S, Benini S, Magagnoli G, Morandi L, Kreshak J, Gambarotti M, Picci P, Zanella L, Alberghini M. Molecular diagnosis in Ewing family tumors. J Mol Diagn. 2011;13:3. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary materials. (PDF 256 KB)