Abstract

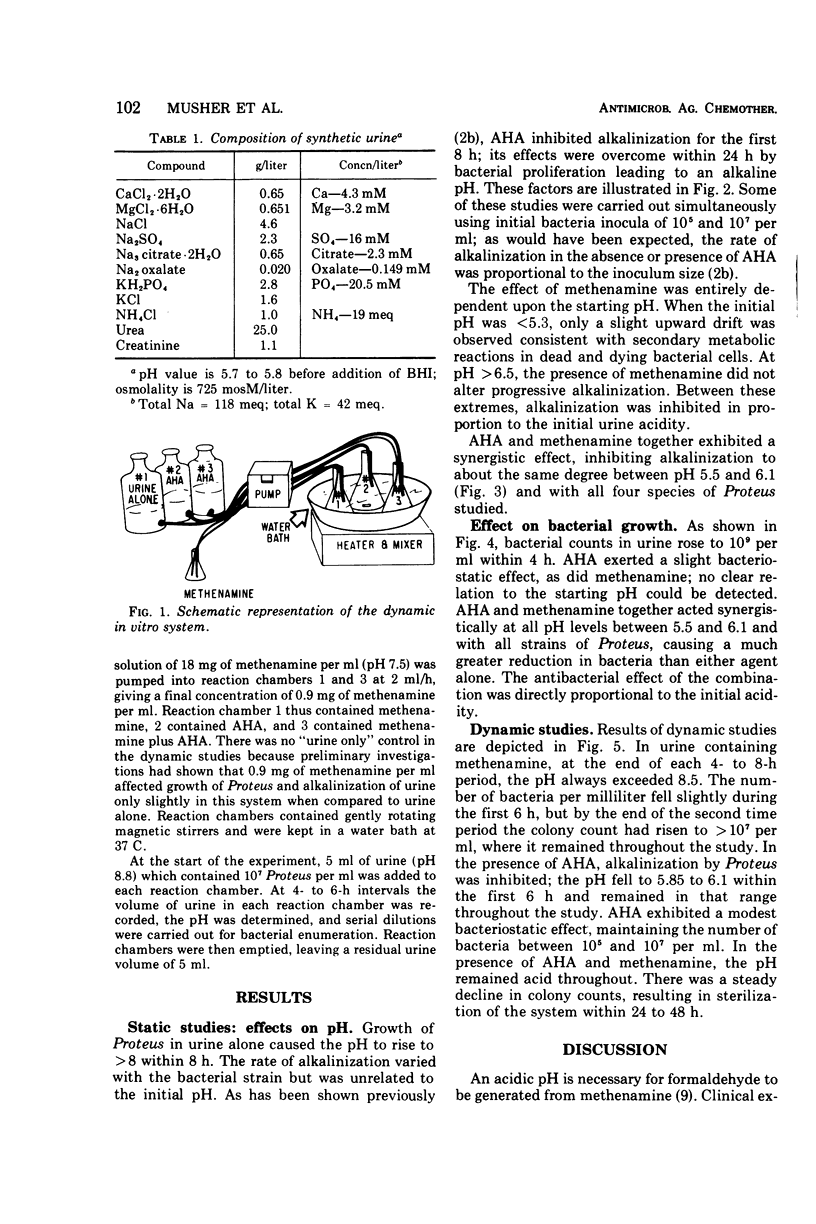

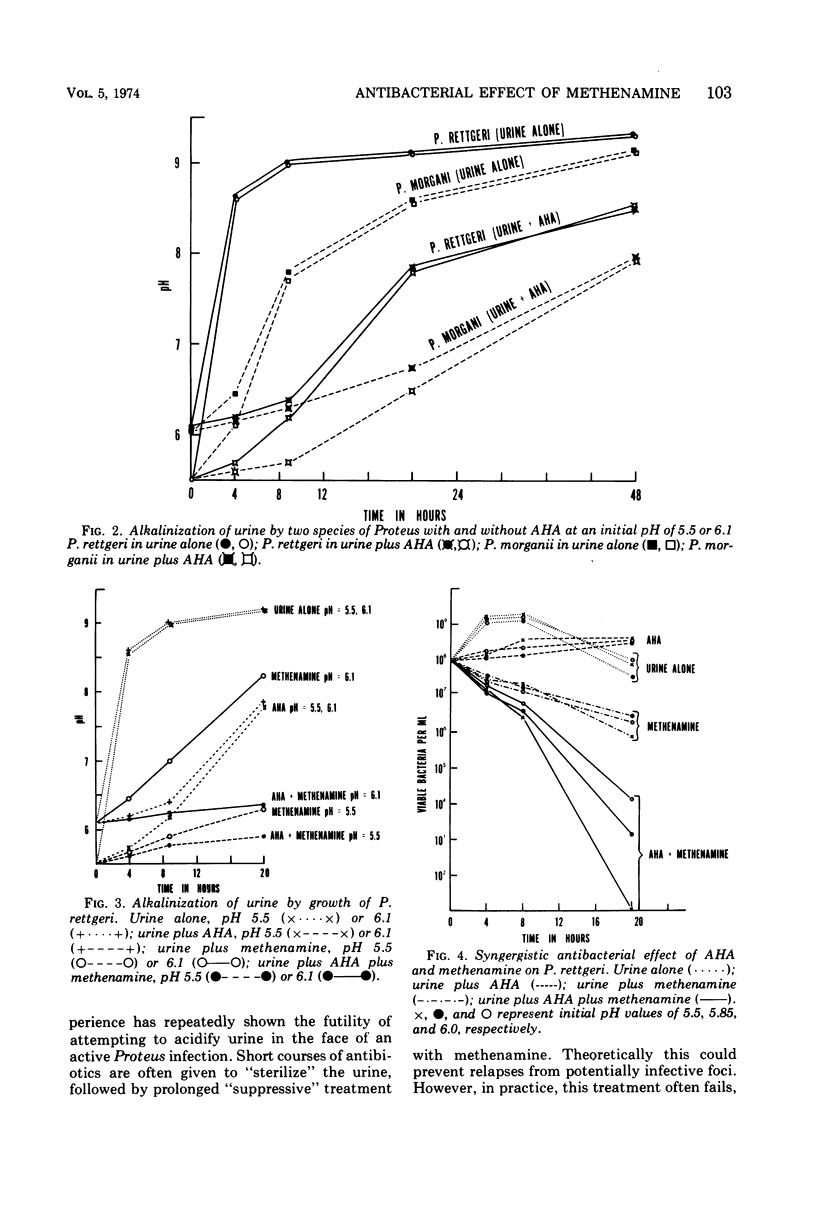

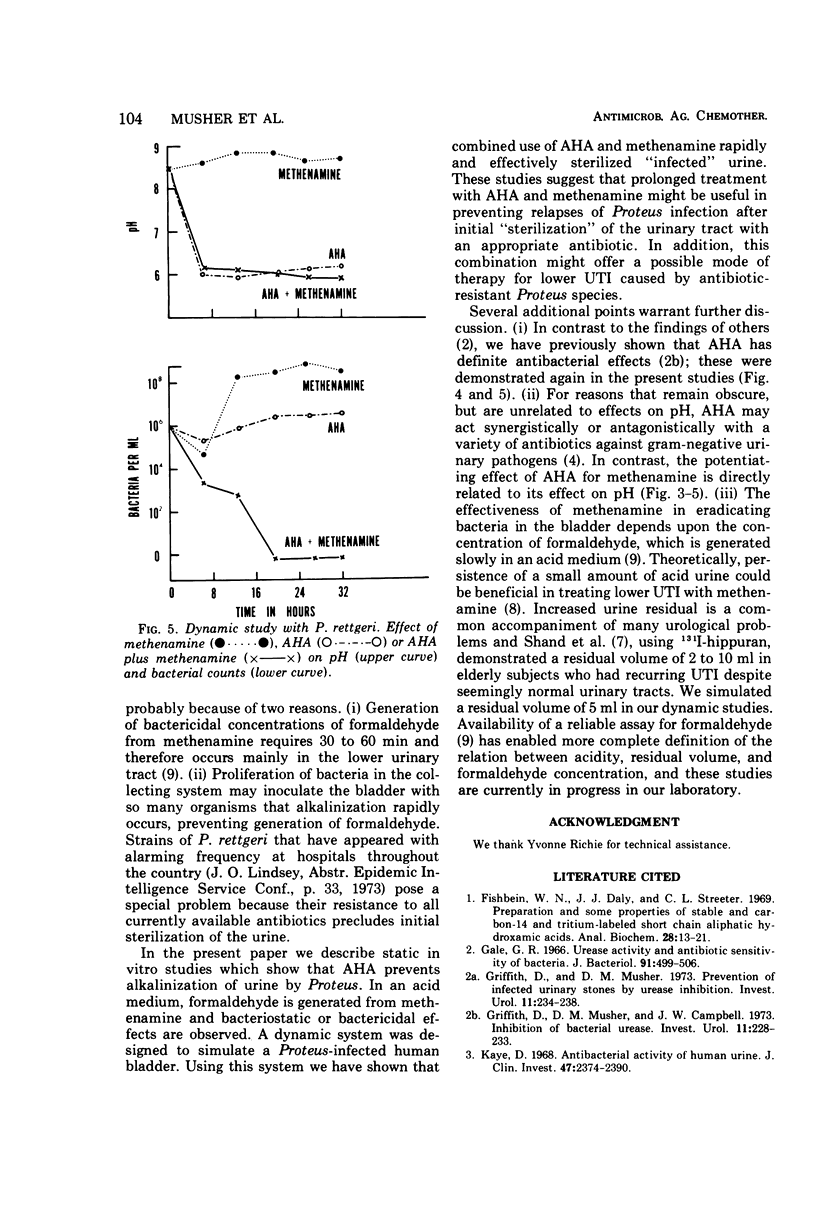

In vitro testing shows nearly all strains of Proteus to be susceptible to methenamine. However, infection by urease-producing bacteria alkalinizes the urine in vivo and prevents generation of formaldehyde, the active metabolite, from methenamine. We have previously shown acetohydroxamic acid (AHA) to be an effective inhibitor of bacterial urease in vitro and in vivo. We now present data obtained by use of static and dynamic in vitro systems, which show that, by preventing urease-induced alkalinization of urine, AHA enables methenamine to exert its antibacterial effect against representative Proteus species.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Fishbein W. N., Daly J., Streeter C. L. Preparation and some properties of stable and carbon-14 and tritium-labeled short-chain aliphatic hydroxamic acids. Anal Biochem. 1969 Apr 4;28(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale G. R. Urease activity and antibiotic sensitivity of bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1966 Feb;91(2):499–506. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.2.499-506.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. P., Musher D. M., Campbell J. W. Inhibition of bacterial urease. Invest Urol. 1973 Nov;11(3):234–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. P., Musher D. M. Prevention of infected urinary stones by urease inhibition. Invest Urol. 1973 Nov;11(3):228–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J., Stamey T. A. The Riker method for determining formaldehyde in the presence of methenamine. Invest Urol. 1971 Sep;9(2):124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye D. Antibacterial activity of human urine. J Clin Invest. 1968 Oct;47(10):2374–2390. doi: 10.1172/JCI105921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye D., Rocha H. Urinary concentrating ability in early experimental pyelonephritis. J Clin Invest. 1970 Jul;49(7):1427–1437. doi: 10.1172/JCI106360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musher D. M., Saenz C., Griffith D. P. Interaction between acetohydroxamic acid and 12 antibiotics against 14 gram-negative pathogenic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1974 Feb;5(2):106–110. doi: 10.1128/aac.5.2.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson W. G., Peacock M., Nordin B. E. Activity products in stone-forming and non-stone-forming urine. Clin Sci. 1968 Jun;34(3):579–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shand D. G., Nimmon C. C., O'Grady F., Cattell W. R. Relation between residual urine volume and response to treatment of urinary infection. Lancet. 1970 Jun 20;760(1):1305–1306. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)91907-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerskill W. H., Thorsell F., Feinberg J. H., Aldrete J. S. Effects of urease inhibition in hyperammonemia: clinical and experimental studies with acetohydroxamic acid. Gastroenterology. 1968 Jan;54(1):20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub W. H., Craddock M. E., Raymond E. A., Fox M., McCall C. E. Characterization of an unusual strain of proteus rettgeri associated with an outbreak of nosocomial urinary-tract infection. Appl Microbiol. 1971 Sep;22(3):278–283. doi: 10.1128/am.22.3.278-283.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert E., Phillips S. F., Summerskill W. H. Ammonia production in the human colon. Effects of cleansing, neomycin and acetohydroxamic acid. N Engl J Med. 1970 Jul 23;283(4):159–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197007232830401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]