Abstract

Background

Clustering of multiple health-compromising behaviours is associated with an increased risk of various chronic diseases. There are few studies on patterns of clustering of multiple health-compromising behaviours in adolescents. Therefore, the aim of this study is to assess how six health-compromising behaviours, namely, low fruit consumption, high sweet consumption, less frequent tooth brushing, low physical activity, physical fighting and smoking, cluster among Saudi male adolescents.

Methods

A representative stratified cluster random sample of 1,335 Saudi Arabian male adolescents living in Riyadh city answered a questionnaire on health-related behaviours. Hierarchical Agglomerative Cluster Analysis (HACA) was used to identify cluster solutions of the six health-compromising behaviours.

Results

HACA suggested two broad and stable clusters for the six health-compromising behaviours. The first cluster included low fruit consumption, less frequent tooth brushing and low physical activity. The second cluster included high sweets consumption, smoking and physical fighting.

Conclusions

The six health-compromising behaviours clustered into two conceptually distinct clusters among Saudi Arabian male adolescents, one reflecting non-adherence to preventive behaviours and the second undertaking of risk behaviours. Clustering of health behaviours has important implications for health promotion.

Keywords: Health behaviours, Clustering, Patterns, Male, Adolescents

Background

Heath-related behaviours such as smoking, alcohol misuse, physical inactivity and unhealthy diets contribute significantly to chronic diseases [1]. Many studies report on interrelationships between some health-related behaviours such as physical activity with healthy eating habits [2], and smoking with eating habits [3]. The interrelationships between health-related behaviours are considered to be multidimensional [4–6]. Roysamb et al. [7] suggested a multidimensional model consisting of three groups of behaviours, namely, “high action”, “addiction” and “protection” behaviours. Moreover, the Problem Behaviour Theory supports the view that the relationships between problem behaviours are multidimensional in nature [8]. The multidimensional approach assumes that certain health-related behaviours tend to cluster in a number of different patterns among both adolescents and adults [9–12]. For example, Raitakari et al. [13] found that a poor diet, smoking, physical inactivity and excessive consumption of alcohol clustered in young adults, while Neumark-Sztainer et al. [14] found associations between different health-compromising behaviours, namely, unhealthy weight loss, substance abuse, suicide risk, delinquency, and sexual activity. In an extensive systematic review of studies published between 1995 and 2003 to identify the clustering of four health-related behaviours (smoking, alcohol abuse, safe sex and healthy nutrition) in adolescents, Wiefferink et al. [15] identified three patterns of clustering. The largest cluster was adolescents who ate healthily, were not smokers and who did not drink alcohol. The second cluster was adolescents who ate unhealthily, smoked and drank alcohol. The third cluster comprised adolescents who ate unhealthily but did not smoke or drink alcohol. Later, Van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. [9] identified two clusters of behaviours for younger adolescents aged 12–15 years, and three clusters for adolescents aged 16–18 years.

Clustering is important because the co-occurrence of multiple health-compromising behaviours is associated with increased risk of chronic diseases including certain cancers and cardiovascular diseases [16]. The increased risk is the result of accumulation and synergistic adverse effects of behaviours on health [17]. Moreover, behavioural patterns in adulthood are primarily shaped during the adolescence period [18]. Therefore, understanding how health-related behaviours relate to one another in adolescents has important implications throughout the life course [19].

Different types of behaviours encompass different aspects of adolescents’ lifestyle. Behaviours related to healthy eating, oral hygiene practices, physical activity, physical fighting, and smoking have a considerable immediate and longer term effect on the health of adolescents and are related to one another. For example, higher fruit intake is associated with increased physical activity [20] and with lower rates of smoking and alcohol consumption [21]. In terms of dietary behaviours, lower fruit intake goes together with higher consumption of sweets and soft drinks and saturated fat [22]. Hygiene behaviour such as toothbrushing frequency, is linked to patterns of smoking [23]. Indeed, smoking is viewed as a “gateway behaviour” to other risky behaviours like drug use and drinking alcohol [24]. The Problem Behaviour Theory postulates that physical fighting is a reliable predictor of multiple risk behaviours such as carrying weapons, injury [25, 26], and substance abuse [27]. Despite these associations between different behaviours, research has generally focused on a limited number of behaviours at a time, with most studies looking at the clustering of two behaviours, thereby limiting understanding of the inter-relationships between different and diverse health-related behaviours among adolescents. Furthermore, these studies have employed basic statistical techniques that either assess only the associations between specific behaviours in a cluster or look at whether the prevalence of predetermined clusters of behaviours is higher than expected; these are correlation coefficients and observed/expected ratios, respectively. While useful, these techniques can only look at behavioural clusters that are predetermined, rather than explore whether the different behaviours form clusters according to theoretical expectations. To address these issues, this study sets out to provide useful insights into clustering and inter-relationships between a wide and diverse range of adolescents’ health-related behaviours. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess how six health-compromising behaviours, namely, low fruit consumption, high sweet consumption, less frequent tooth brushing, low physical activity, physical fighting and smoking cluster together among male adolescents in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Subjects were Saudi males in two age groups: 13–14 year old students in 8th grade intermediate schools and 17–19 year old students in 12th grade secondary schools. These two age groups were considered to represent respectively the onset of physical and emotional changes in early adolescence, and later adolescence when young people are about to choose their future careers and have a greater degree of autonomy [28]. For practical local reasons, females could not be included in the study because all researchers were males, and men are not allowed to enter schools for girls in Saudi Arabia. Public and private schools for intermediate and secondary stages were selected. The samples were randomly selected from 515 intermediate and secondary schools in Riyadh. Schools for special needs children were excluded. Based on recommendations of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) international protocol, a cluster design was used [29]. The sampling frame was the list of schools for the whole Riyadh city. Stratified cluster random sampling was used to produce more precision and better representatives of the study population. The sampling frame was divided into four strata (public intermediate schools, public secondary schools, private intermediate schools, and private secondary schools). Schools were selected from each stratum by simple random sampling. As young and older adolescents were required for the study, all classes of only Grade 8 and Grade 12 in the selected schools were recruited. All students attending the selected classes on the day of the survey were invited to participate.

The sample size calculation was based on estimates of behavioural clustering from a pilot study and considered power of 80%, a = 0.05, a design factor of 1.2 to account for cluster sampling and 20% over-sampling for non-response. The calculated minimum final sample size was 980 students. For a representative sample of the relevant population in Riyadh, a self-weighting sample was used to select students from each stratum with the same proportion as in the general population [30]. That resulted in a sample size of 1100 students.

A self-administered classroom-based questionnaire used in the WHO cross-national study on Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) was adapted for use in this study [29]. The questionnaire included health-related behaviours, demographic characteristics, parent’s occupation and school environment. The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into Arabic by two qualified translators who were native speakers of Arabic and proficient in English. After that, the consensus Arabic questionnaire was backward translated into English and the backward translation was reviewed and compared for discrepancies with the original version [31]. No major differences were found. In addition, the Arabic questionnaire was reviewed by an expert teacher and then tested in a pilot study.

This study was approved by the University College London (UCL) Research Ethics Committee and the General Administration of Education at Riyadh Region, Saudi Arabia. Informed consent forms and information sheets were distributed through schools to parents and guardians. Positive parental written consent for all participants was received prior to the commencement of data collection. In conformity with procedures stipulated in the HBSC protocol [29], students were assured about anonymity and confidentiality of their responses. They were also given appropriate written and verbal instructions by the principal author (SA) at the beginning of the anonymised questionnaire.

Measures

Dietary behaviours included weekly frequency of eating fruit and sweets (never, less than once a week, once a week, 2–4 days a week, 5–6 days a week, once a day every day, more than once every day)[29]. Tooth brushing frequency was reported as “More than once a day, once a day, at least once a week but not daily, less than once a week, never”[32]. Physical activity was assessed through the 60 minute Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity (MVPA) measure [33]. Physical fight frequency in the past year reported as “I have not been in a physical fight in the past 12 months” to “four times or more”[34]. Smoking was measured by “How often do you smoke tobacco at present?” Response options ranged from: “Every day” to “I do not smoke”[29].

Statistical analysis

The six health-related behaviours had different categorizations ranging from 4 to 7 categories. In order to make them directly comparable, they were dichotomized into binary variables (0 = healthy behaviour; and 1 = health-compromising behaviour) based on public health recommendations. Fruit consumption was dichotomized into once or more daily vs. less than once daily; sweet consumption into less than once daily vs. once or more daily; tooth brushing into twice or more daily vs. less than twice daily. For physical activity, an answer of 5 days or more per week indicates meeting physical activity recommendations, while less than 5 days per week indicates not meeting recommendations [33]. Physical fighting was categorised into none vs. one time or more in the last 12 months. Tobacco smoking was grouped into non-smoker and current smoker (at least once per week).

Pairwise correlations using Phi test for binary variables were used. Analysis of clustering was based on the Hierarchical Agglomerative Cluster Analysis (HACA). HACA is the most appropriate approach in identifying clusters of health-related behaviours [35–37]. It produces more stable cluster solutions compared to non-Hierarchical Cluster Analysis, and allows grouping of subjects that have similar characteristics across different variables leading to homogenous empirical types [35, 37]. Following guidance from the literature [37], the stability of the clusters was verified by repeating the HACA on different sub-samples drawn randomly from the study sample. The stability of the identified clusters is also essential for their validity. Furthermore, we also calculated the correlation coefficients between the different behaviours of each identified clusters as another approach to validate the identified cluster structures [36]. HACA was therefore used to identify stable cluster solutions for the multiple health-compromising behaviours, through an average linkage algorithm between groups that identified homogenous subgroups within the heterogeneous sample. We used Squared Euclidean distance as the measure of proximity, as it is suitable for binary variables [36]. The number of identifiable clusters was not known a priori. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows, version 16.0/PC; SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Of the 515 schools in Riyadh, 22 were randomly selected and agreed to participate in the study. We invited 1,354 eligible students to participate. There were no refusals by students or parents, but 19 questionnaires were excluded from the analysis because they were not fully completed. Therefore, the analytical sample was 1,335 students.

More than half the sample (54%) were 17–19 years old, and 52% of the adolescents attended public schools. About 85% of adolescents ate fruit less than once daily, 74% brushed their teeth less than twice daily, 64% had low physical activity, 51% had been involved in physical fighting at least once or more in the last 12 months, 43% ate sweets once or more daily and 23% smoked tobacco (Table 1). Low fruit consumption was positively correlated with low physical activity and less frequent tooth brushing (p < 0.01). Smoking was positively correlated with physical fighting and high sweet consumption (p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 13-14 years | 613 | 45.9 |

| 17-19 years | 722 | 54.1 |

| School type | ||

| Private | 640 | 47.9 |

| Public | 695 | 52.1 |

| Health-compromising behaviours | ||

| Low fruit consumption (Less than once daily) | 1130 | 84.6 |

| High sweet consumption (Once or more daily) | 579 | 43.4 |

| Less frequent toothbrushing (Less than twice daily) | 991 | 74.2 |

| Low physical activity (Less than 5 days per week of MVPA) | 850 | 63.7 |

| Physical fighting (One time or more per year) | 677 | 50.7 |

| Smoking (At least once or more per week) | 312 | 23.4 |

Table 2.

Pairwise correlations between health-compromising behaviours

| Low fruit consumption | High sweet consumption | Less frequent toothbrushing | Low physical activity | Physical fighting | Smoking | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low fruit consumption | 1 | |||||

| High sweet consumption | -0.03 | 1 | ||||

| Less frequent toothbrushing | 0.08** | 0.03 | 1 | |||

| Low physical activity | 0.12** | -0.01 | 0.03 | 1 | ||

| Physical fighting | -0.002 | 0.02 | -0.03 | -0.03 | 1 | |

| Smoking | -0.004 | 0.08** | 0.03 | 0.11** | 0.08** | 1 |

**Phi correlation was significant p < 0.001.

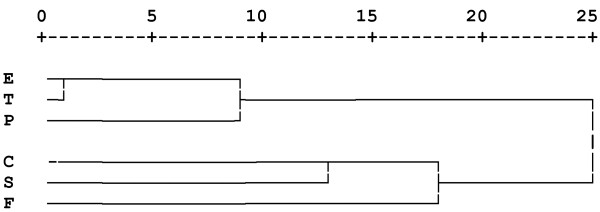

Figure 1 shows the hierarchical tree plot (dendrogram) which is a visual presentation of the distance (agglomeration schedules) at which clusters are combined. Pairs of variables with smaller distances were more similar and were combined with average linkage in a group, while the variables with larger distances indicate the least homogenous groups [36]. Based on the proximity coefficients, low fruit consumption (E) and less frequent tooth brushing (T) were combined together in one group. After that, low physical activity (P) was also combined with E and T to form a cluster (Cluster 1). In the third stage, high sweet consumption (C) and smoking (S) formed a new group. In the fourth stage, physical fighting (F) combined with C and S to form a new cluster (Cluster 2). At stage four, there were two distinct clusters, with large distances (agglomeration coefficients) between them, thereby representing the best solution for this study population. These two distinct clusters with different patterns of health-compromising behaviours collectively included all six health-related behaviours.

Figure 1.

Tree diagram of hierarchical agglomerative cluster analysis of the six health-related behaviours. The dendrogram provides a visual presentation of the distance at which clusters are combined. It is read from left to right and the vertical lines show joined clusters. The position of the vertical line on the scale indicates the distance at which clusters are joined. Variables with smaller distance have higher homogeneity and they are combined with a vertical line linking them in a cluster, while the variables with larger distance indicate the least homogenous clusters. The distances (agglomeration coefficients) displayed in the top of the plot are rescaled (by default) to fall into a range of 1 to 25.

The first cluster at the top of the dendrogram plot consisted of low fruit consumption, less frequent tooth brushing and low physical activity. The second cluster at the bottom of the dendrogram plot included high sweet consumption, smoking and physical fighting. The stability and validity of the clusters was confirmed by repeating the HACA on different sub-samples drawn randomly from the study sample. Also, significant associations between the variables in each cluster validated the cluster structure (Table 2).

Discussion

The HACA analysis identified two broad and stable clusters of health-compromising behaviours. The first cluster included low fruit consumption, less frequent tooth brushing and low physical activity, and the second cluster included high sweets consumption, smoking and physical fighting. These two clusters are quite distinct conceptually, with the first reflecting non-adherence to preventive behaviours, while the second, to undertaking risk behaviours. Previous studies reported associations between low fruit and vegetables consumption and low physical activity in adolescence [9, 38–41], and between tooth brushing and eating habits [42]. However, those studies only reported associations between two behaviours at a time, and did not look at clustering patterns of multiple health-related behaviours. Our findings go further in terms of identifying distinct clusters of multiple health-related behaviours. For example, we showed that less frequent tooth brushing clustered with low fruit consumption and low physical activity.

The second cluster (high sweets consumption, smoking and physical fighting) agrees partly with a systematic review that reported a significant association between high sweet consumption and smoking [21], while another study showed significant association between substance abuse and fighting [27]. The above-mentioned studies only reported associations between two behaviours. One potential explanation for our results showing a cluster of high sweet consumption, smoking and physical fighting is that these behaviours may have determinants in common [43]. For example, delinquency and rebellious behaviours might be important risk factors in adolescents, especially for clustering of smoking with physical fighting [9].

Previous research indicated that health-related behaviours were not independent of each other [5] and their interrelationships were multidimensional [4, 44]. Furthermore, the present study used statistical methods, the HACA, not used heretofore to assess clustering of health-related behaviours. The HACA is a rigorous methodological tool that can be used to highlight the multidimensional relationships between health-related behaviours. It gives more stable cluster solutions compared to non-Hierarchical Cluster Analysis. Though it was used here in an exploratory manner, it has been used extensively in other research fields [37]. Our results confirmed that HACA is a valuable method to identify clustering of health-related behaviours.

This is the first study on the prevalence and clustering of multiple health-related behaviours among a representative sample of Saudi Arabian male adolescents. We used established data collection tools, adapted from the HBSC [29], and had a very high response rate due to excellent cooperation from the adolescents in the selected schools. Moreover, a wide variety of important health-related behaviours among adolescents were included. However, this study has certain limitations. It was conducted only in Riyadh city, which might explain the relatively homogeneous study population. Also, for reasons beyond our control, girls were not included in this study. The data are self–reported, therefore might be subject to recall and social desirability bias. However, previous research showed that confidentiality and anonymity of self-reports reduces bias and provides reliable and valid data [45]. The six health-related behaviours were dichotomized which might lead to loss of some information about individual differences [46]. As the health-related behaviours included in this study had different scales and categories, dichotomization based on public health recommendations was considered appropriate to assess clustering of multiple health-related behaviours with same metric.

Our results have important implications for public health practice. Showing that there are two distinct and broad clusters of health-compromising behaviours emphasizes the importance of a cluster-based approach in health promotion intervention planning and the potential greater impact of targeting multiple health-related behaviours [47, 48]. Oral health-related behaviours were clustered with general health-related behaviours. That emphasizes the importance of multidisciplinary health promotion interventions using the Common Risk Factor Approach [49].

Conclusions

The six health-compromising behaviours (low fruit consumption, high sweet consumption, less frequent tooth brushing, low physical activity, physical fighting and smoking) clustered into two clusters. One cluster contained health-compromising behaviours; not conforming to preventive behaviours for fruit consumption, physical activity and tooth brushing. The other cluster consisted of risk-taking behaviours such as smoking, physical fighting and high sweets consumption. These two stable clusters appear to be representative clusters among Saudi Arabian male adolescents in Riyadh city.

Acknowledgements

We thank the sponsor, the Ministry of Education and the schools and students who participated in this study. We also thank Mr. Saud Alruhaimi for helping in data collection.

Abbreviations

- HACA

Hierarchical Agglomerative Cluster Analysis

- HBSC

Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children

- MVPA

Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity

- E

Low fruit consumption

- T

Less frequent tooth brushing

- P

Low physical activity

- C

High sweet consumption

- S

Smoking

- F

Physical fighting.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SGA, RGW, AS and GT conceived the original research question. SGA undertook the data analysis with the support of MA and GT. All authors were involved in drafting and finalizing the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Saeed G Alzahrani, Email: sgalsaeed@imamu.edu.sa.

Richard G Watt, Email: r.watt@ucl.ac.uk.

Aubrey Sheiham, Email: a.sheiham@ucl.ac.uk.

Maria Aresu, Email: m.aresu@ucl.ac.uk.

Georgios Tsakos, Email: g.tsakos@ucl.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Viner RM, Haller DM, Bose K, Vos T, Ferguson J, Mathers CD. Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2009;374:881–892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60741-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pate RR, Heath GW, Dowda M, Trost SG. Associations between physical activity and other health behaviors in a representative sample of US adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1577–1581. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.11.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coulson NS, Eiser C, Eiser JR. Diet, smoking and exercise: interrelationships between adolescent health behaviours. Child Care Health Dev. 1997;23:207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.1997.tb00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steele JL, McBroom WH. Conceptual and empirical dimensions of health behavior. J Health Soc Behav. 1972;13:382–392. doi: 10.2307/2136830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AF, Wechsler H. Interrelationship of preventive actions in health and other areas. Health Serv Rep. 1972;87:969–976. doi: 10.2307/4594704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terre L, Drabman RS, Meydrech EF. Relationships among children's health-related behaviors: a multivariate, developmental perspective. Prev Med. 1990;19:134–146. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(90)90015-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roysamb E, Rse J, Kraft P. On the structure and dimensionality of health-related behaviour in adolescents. Psychol Health. 1997;12:437–452. doi: 10.1080/08870449708406721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth New York: Academic Press. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Nieuwenhuijzen M, Junger M, Velderman MK, Wiefferink KH, Paulussen TWGM, Hox J, Reijneveld SA. Clustering of health-compromising behavior and delinquency in adolescents and adults in the Dutch population. Prev Med. 2009;48:572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ottevaere C, Huybrechts I, Benser J, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Cuenca-Garcia M, Dallongeville J, Zaccaria M, Gottrand F, Kersting M, Rey-Lopez J, Manios Y, Molnar D, Moreno L, Smpokos E, Widhalm K, De Henauw S, the HELENA Study Group Clustering patterns of physical activity, sedentary and dietary behavior among European adolescents: The HELENA study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:328–338. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busch V, Van Stel H, Schrijvers A, de Leeuw J. Clustering of health-related behaviors, health outcomes and demographics in Dutch adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patterson RE, Haines PS, Popkin BM. Health lifestyle patterns of U.S. adults. Prev Med. 1994;23:453–460. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raitakari OT, Leino M, Rakkonen K, Porkka KV, Taimela S, Rasanen L, Viikari JS. Clustering of risk habits in young adults. The cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:36–44. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, French S, Cassuto N, Jacobs DR, Jr, Resnick MD. Patterns of health-compromising behaviors among Minnesota adolescents: sociodemographic variations. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1599–1606. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.11.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiefferink CH, Peters L, Hoekstra F, Dam GT, Buijs GJ, Paulussen TG. Clustering of health-related behaviors and their determinants: possible consequences for school health interventions. Prev Sci. 2006;7:127–149. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng L, Maskarinec G, Lee J, Kolonel LN. Lifestyle factors and chronic diseases: application of a composite risk index. Prev Med. 1999;29:296–304. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khaw KT, Wareham N, Bingham S, Welch A, Luben R, Day N. Combined impact of health behaviours and mortality in Men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelder SH, Perry CL, Klepp KI, Lytle LL. Longitudinal tracking of adolescent smoking, physical activity, and food choice behaviors. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1121–1126. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.7.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawlor DA, O'Callaghan MJ, Mamun AA, Williams GM, Bor W, Najman JM. Socioeconomic position, cognitive function, and clustering of cardiovascular risk factors in adolescence: findings from the mater university study of pregnancy and its outcomes. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:862–868. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188576.54698.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C, Buchner D, Ettinger W, Heath GW, King AC, Kriska A, Leon AS, Marcus BH, Morris J, Paffenbarger RSJ, Patrick K, Pollock ML, Rippe JM, Sallis J, Wilmore JH. Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the centers for disease control and prevention and the American college of sports medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520290054029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dallongeville J, Marecaux N, Fruchart JC, Amouyel P. Cigarette smoking is associated with unhealthy patterns of nutrient intake: a meta-analysis. J Nutr. 1998;128:1450–1457. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.9.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Currie C, Gabhainn SN, Godeau E, Roberts C, Smith R, Currie D, Picket W, Richter M, Morgan A, Barnekow V. Inequalities in Young People's health, HBSC International Report from 2005/2006 Survey. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regoinal Office For Europe; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park Y, Patton L, Kim H. Clustering of oral and general health risk behaviors in Korean adolescents: a national representative sample. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:277–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torabi MR, Bailey WJ, Majd-Jabbari M. Cigarette smoking as a predictor of alcohol and other drug Use by children and adolescents: evidence of the "gateway drug effect". J Sch Health. 1993;63:302–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1993.tb06150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pickett W, Craig W, Harel Y, Cunningham J, Simpson K, Molcho M, Mazur J, Dostaler S, Overpeck MD, Currie CE, on behalf of the HBSC Violence and Injuries Writing Group Cross-national study of fighting and weapon carrying as determinants of adolescent injury. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e855–e863. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sosin DM, Koepsell TD, Rivara FP, Mercy JA. Fighting as a marker for multiple problem behaviors in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1995;16:209–215. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)00093-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuntsche EN, Gmel G. Emotional wellbeing and violence among social and solitary risky single occasion drinkers in adolescence. Addiction. 2004;99:331–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO . Adolescent Friendly Health Services. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Currie C, Samdal O, Boyce W, Smith B. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children: a World Health Organisation Cross-National Study. Research Protocol for the 2001/02 Survey. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters TJ, Eachus JI. Achieving equal probability of selection under various random sampling strategies. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1995;9:219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1995.tb00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Honkala S, Honkala E, Al-Sahli N. Do life- or school-satisfaction and self-esteem indicators explain the oral hygiene habits of schoolchildren? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:337–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prochaska JJ, Sallis JF, Long B. A physical activity screening measure for Use with adolescents in primary care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:554–559. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brener ND, Collins JL, Kann L, Warren CW, Williams BI. Reliability of the youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:575–580. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borgen FH, Barnett DV. Applying cluster analysis in counseling psychology research. J Couns Psychol. 1987;34:456–468. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.34.4.456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Everitt BS, Landau S, Leese M. Cluster Analysis. 4. London: Arnold; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clatworthy J, Buick D, Hankins M, Weinman J, Horne R. The use and reporting of cluster analysis in health psychology: a review. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10:329–358. doi: 10.1348/135910705X25697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanchez A, Norman GJ, Sallis JF, Calfas KJ, Cella J, Patrick K. Patterns and correlates of physical activity and nutrition behaviors in adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alamian A, Paradis G. Clustering of chronic disease behavioral risk factors in Canadian children and adolescents. Prev Med. 2009;48:493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mistry R, McCarthy WJ, Yancey AK, Lu Y, Patel M. Resilience and patterns of health risk behaviors in California adolescents. Prev Med. 2009;48:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pearson N, Atkin A, Biddle S, Gorely T, Edwardson C. Patterns of adolescent physical activity and dietary behaviours. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;2009:34. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schou L, Currie C, McQueen D. Using a "lifestyle" perspective to understand toothbrushing behaviour in Scottish schoolchildren. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18:230–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12:597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(91)90007-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris DM, Guten S. Health-protective behavior: an exploratory study. J Health Soc Behav. 1979;20:17–29. doi: 10.2307/2136475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brener ND, Billy JOG, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33:436–457. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nigg CR, Allegrante JP, Ory M. Theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research: common themes advancing health behavior research. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:670–679. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Vries H, van't Riet J, Spigt M, Metsemakers J, van den Akker M, Vermunt JK, Kremers S. Clusters of lifestyle behaviors: results from the Dutch SMILE study. Prev Med. 2008;46:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheiham A, Watt RG. The common risk factor approach: a rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:399–406. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028006399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pre-publication history

- The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/1215/prepub